Dear Editor,

With its advantages of simple design and cost-efficiency, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been widely adapted for genome editing in different species including zebrafish1. In zebrafish studies, guide RNA (gRNA) is usually produced via in vitro transcription followed by microinjection with Cas9 mRNA into embryos. The vectors currently used for production of gRNA contain either a T7 or SP6 promoter in vitro or U6 promoter in vivo. Among these, T7 promoter is most popularly used due to its high efficiency and, therefore, limits the gRNA targeting sites to an optimal “GG-N18-NGG” format2. This limitation significantly reduces the usable “N20-NGG” sites for gene editing by CRISPR/Cas9. Csy4 was first identified as an endoribonuclease that cleaves RNA bearing a hairpin sequence to release gRNAs used for adaptive immunity in the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa3,4,5. Csy4 selectively recognizes a 16-nt sequence with exceptionally high affinity and specificity4. Recently, it was reported that the application of Csy4 permits multiplex expression of gRNAs bearing any 5′ nucleotide in human cells, allowing the use of the U6 promoter to produce gRNAs without restriction by the “5′-G”6. It would be useful if such a system could be adopted in vivo, especially in zebrafish.

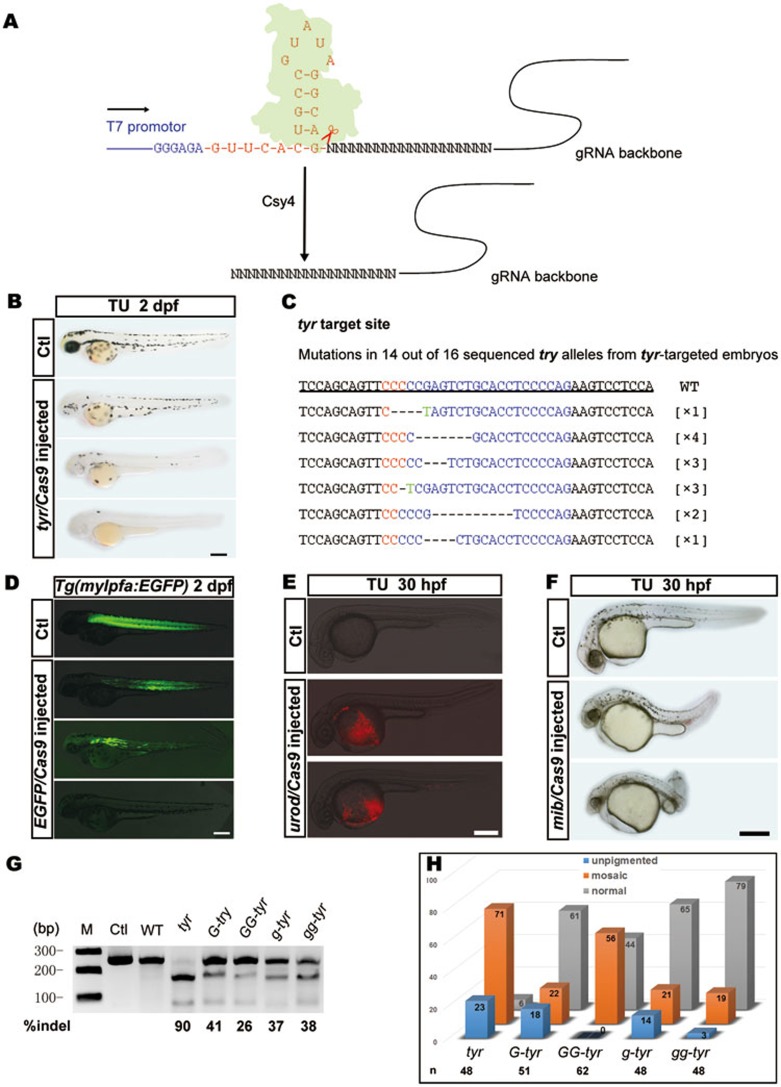

To test Csy4-based gRNA cleavage in zebrafish, we first targeted the tyrosinase (tyr) gene, which encodes an enzyme that converts tyrosine into melanin. Loss of tyr function thus leads to pigmentation defects. We randomly selected a tyr gRNA site near the start codon without “GG” at the 5′ end. Since gRNA can be transcribed from synthetic oligonucleotides efficiently in vitro, we constructed a Csy4-gRNA template (Figure 1A) using overlap PCR and, thus, omitting the time-consuming cloning procedures. We added “5′-GGGAGA-3′” as the T7 core promoter sequence in front of the template to increase T7 transcription efficiency. Following the T7 promoter sequence, the template encodes a Csy4 binding site for cleavage of the RNA transcript by Csy4 protein, thereby releasing a desirable gRNA (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Overview of the Csy4 cleavage system and analysis of injected F0 founders. (A) Schematic illustration of Csy4-mediated pre-gRNA cleavage. Pre-gRNA with a target-binding site (N20) was transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase and then incubated with Csy4 protein (green) in vitro. A final gRNA product without GG-limitation was released. (B) Lateral views of wild-type (WT) and tyr-targeted embryos at 2 dpf. Tyr-targeted embryos showed different degrees of hypopigmentation. (C) WT sequence and sequences showing indels derived from tyr gRNA/Cas9 injected founders. Blue color represents target sequence of tyr; red color indicates PAM region; “-” indicates deletion; green color indicates mutations. The number in brackets represents the times of the identified mutant allele. (D-F) Analysis of gRNAs generated by Csy4 targeting selected sites without “GG” at the 5′ end. Lateral views of WT (top, Ctl), EGFP, urod and mib-targeted embryos (lower panels). Scale bar = 300 μm. (G) Targeting efficiency analyzed by T7EI assays. Ctl: the PCR sample not treated; WT: the uninjected group; G-tyr: one G nucleotide added at 5' end of tyr gRNA; GG-tyr: two G nucleotides added at 5′ end of the tyr gRNA; g-tyr: the first “C” nucleotide was changed to “G” gg-tyr: the initial “CT” nucleotides were changed to “GG”. Note that tyr gRNA produced over 90% DNA with indels whereas mismatched tyr gRNAs only induced 26%-41% indels. Scale bar = 300 μm. (H) Statistic analysis of efficiency of different tyr gRNAs. Injected embryos showing <10 pigmented melanophores were considered as unpigmented.

First, we co-injected csy4 mRNA, Cas9 mRNA and Csy4-gRNA into zebrafish embryos to target tyr. Unexpectedly, we found that all injected embryos exhibited severe malformation at about 18 h post fertilization. This was confirmed to be caused by Csy4 as injection of csy4 mRNA or Csy4 protein alone resulted in the same phenotype (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Since no endogenous Csy4 targeting sequences are identified in its genome, why this occurs in zebrafish will be an interesting subject for future studies.

To overcome this problem, we purified recombinant Csy4 protein using Escherichia coli expression (Supplementary information, Figure S1B). After incubation of Csy4 protein with the transcript containing the tyr targeting site from Csy4-gRNA template, we obtained abundant tyr gRNA (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). Injection of the tyr gRNA with Cas9 mRNA resulted in pigmentation reduction in nearly all of the injected embryos, with some completely lacking pigmentation (Figure 1B). Sequencing analyses also confirmed multiple insertions/deletions (indels) at the targeted site (Figure 1C). This suggests that the gRNA excised by Csy4 protein functions efficiently for gene targeting in zebrafish.

Next we investigated whether this strategy could be applied to target multiple genes including EGFP, urod and mib. Considering mutations in N-terminal region should be more efficient in inducing loss of function, we randomly selected “N20-NGG” sites near the translational initiation codon. Using the Csy4-gRNA template, we obtained pre-RNAs for all selected sites and produced the corresponding gRNAs by incubation with Csy4 protein. For the EGFP, we injected Cas9/gRNA into the tg (mylpfa:EGFP) transgenic fish, where muscle cells are labeled by EGFP. Complete or partial loss of EGFP expression was observed in the injected embryos (Figure 1D). UROD is a heme biosynthesis enzyme and zebrafish urod mutant exhibits fluorescent erythrocytes7. We observed the same phenotype after injection of the gRNA for urod (Figure 1E). Mind bomb (mib) gene encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase, a component of Notch signaling8. Disrupting mib by our Cas9/gRNA led to the same phenotype as the mib mutant, including smaller heads/eyes and curved bodies (Figure 1F). T7E1 mutagenesis assay and sequencing confirmed effective indels of genes induced by these gRNAs generated from “N20-NGG” sites (Supplementary information, Figure S2). Since the “N20-NGG” format enables easier selection of gRNAs targeting N-termini of protein, it is conceivable that gene functions could be studied in F0 generation by using the approach described here.

For gene targeting, it is highly desirable to be able to edit a specific site based on naturally occurring mutations. This would facilitate homologous recombination directed editing for mutation correction or creation in animal models. The human mutation in SUSD4 gene is apparently linked to a complicated group of diseases including diabetes, pain and neurodegeneration. One mutation variant is found at codon 778 from C to A, changing amino acid from Pro260 to Thr260. This mutation was identified by the NIH Undiagnosed Disease Program (http://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/research/pages/27/undiagnosed-diseases-program) through patient-specific genomic sequencing for mutations associated with rare and undiagnosed diseases. SUSD4 is highly conserved and protein sequences near Pro260 are identical between the human and zebrafish gene. Previous reports demonstrated that single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) could be an effective donor for homology-directed repair-based genome editing coupled with CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) in zebrafish embryos9,10. To introduce the same point mutation into zebrafish genome using this method, we needed to induce DNA DSBs precisely at the location of the genome corresponding to Pro260. In this case, there would be no gRNA sites near the desired targeting locus if the “GG-N18-NGG” or “G-N19-NGG” format is used. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3A, we were able to identify two functional gRNAs overlapping the locus of Pro260 by our strategy and one of them showed over 70% efficiency of generating indels. After co-injection of an ssDNA oligonucleotide and this gRNA/Cas9, 3 out of 16 randomly selected F0 embryos had the correct single-base change resulting in a point mutation of Pro260 to Thr260 (Supplementary information, Figure S3B).

Previous studies have shown that gRNAs could tolerate 2-nt mismatches at their 5′ end11. Nonetheless, a recent report suggests that any mismatch to the 5′-GG could reduce gRNA efficiency12. We also investigated this issue by designing mismatched gRNAs targeting the tyr site and found that efficiency of the mismatched gRNAs was notably lower than that produced by Csy4 cleavage (26%-41% vs 90% indels, Figure 1G and 1H). Similarly, mismatched gRNAs reduced mutagenesis efficiency for the sites of urod and mib (5%-13% vs 80% indels for urod, 25%-39% vs 55% indels for mib, Supplementary information, Figure S4A and S4B). This finding is consistent with result from a recent large-scale study of 162 loci showing that CRISPR targets with a mismatched “G” at the 5′ end have a significantly lower rate of mutagenesis than those with a native G (the median frequency being 20% compared to 67% for the gRNAs with a GG match at the 5′ end)13. Overall, these studies support that any change at the 5′ end indeed reduces the gRNA targeting efficiency.

In conclusion, we have developed a procedure that uses Csy4 protein to efficiently synthesize gRNA. This method enables synthesis of gRNAs in an “N20-NGG” format and theoretically extends the targeting range to 1 in every 8 bps. This system should significantly expand the utility of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology in zebrafish and other models requiring injection of in vitro transcribed gRNAs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jason Ear for editing the paper, Chen Shen for technical assistance and Zenghou Tang for zebrafish husbandry. This work was in part supported by funding from Science and Technology Program of Shenzhen, China (CXZZ20140903101756864).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Injection of Csy4 mRNA results in severe malformation in zebrafish and expression of Csy4 protein.

T7 endonuclease I assays and sequencing results of different Cas9/gRNAs injected F0 embryos.

T7EI assays and sequencing results at the susd4 target.

Comparison of targeting efficiency of gRNAs produced by Csy4 and T7 polymerase with mismatches.

Primers used in this study.

Materials and Methods

References

- Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF. Trends Biotechnol. 2013. pp. 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2013. pp. 227–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haurwitz RE, Jinek M, Wiedenheft B, et al. Science. 2010. pp. 1355–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sternberg SH, Haurwitz RE, Doudna JA. RNA. 2012. pp. 661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haurwitz RE, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. EMBO J. 2012. pp. 2824–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tsai SQ, Wyvekens N, Khayter C, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2014. pp. 569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Long Q, Marty SD, et al. Nat Genet. 1998. pp. 239–243. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Itoh M, Kim CH, Palardy G, et al. Dev Cell. 2003. pp. 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bedell VM, Wang Y, Campbell JM, et al. Nature. 2012. pp. 114–U133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dong Z, Dong X, Jia W, et al. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014. pp. 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, et al. PloS One. 2013. p. e68708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gagnon JA, Valen E, Thyme SB, et al. PloS One. 2014. p. e98186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Varshney GK, Pei W, LaFave MC, et al. Genome Res. 2015. pp. 1–13.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Injection of Csy4 mRNA results in severe malformation in zebrafish and expression of Csy4 protein.

T7 endonuclease I assays and sequencing results of different Cas9/gRNAs injected F0 embryos.

T7EI assays and sequencing results at the susd4 target.

Comparison of targeting efficiency of gRNAs produced by Csy4 and T7 polymerase with mismatches.

Primers used in this study.

Materials and Methods