Abstract

Context:

Professional responsibility, rewards and respect, and time for rejuvenation are factors supporting professional commitment for athletic trainers (ATs) in the high school setting. The inherent complexities of an occupational setting can mitigate perceptions of professional commitment. Thus far, evidence is lacking regarding professional commitment for ATs in other occupational settings.

Objective:

To extend the literature on professional commitment of the AT to the collegiate setting.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

Collegiate.

Patients or Other Participants:

Thirty-three Board of Certification-certified ATs employed in the collegiate setting (National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I = 11, Division II = 9, Division III = 13) with an average of 10 ± 8 years of clinical experience volunteered. Data saturation guided the total number of participants.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Online journaling via QuestionPro was used to collect data from all participants. Two strategies, multiple-analyst triangulation and peer review, were completed to satisfy data credibility. Data were evaluated using a general inductive approach.

Results:

Likert-scale data revealed no differences regarding levels of professional commitment across divisions. Two themes emerged from the inductive-content analysis: (1) professional responsibility and (2) coworker support. The emergent theme of professional responsibility contained 4 subthemes: (1) dedication to advancing the athletic training profession, (2) ardor for job responsibilities, (3) dedication to the student-athlete, and (4) commitment to education. Our participants were able to better maintain their own professional commitment when they felt their coworkers were also committed to the profession.

Conclusions:

The collegiate ATs investigated in this study, regardless of division, demonstrated professional commitment propelled by their aspiration to advance the profession, as well as their dedication to student-athletes and athletic training students. Maintaining commitment was influenced by a strong sense of coworker support.

Key Words: learning, professional responsibility, support

Key Points

Collegiate athletic trainers were internally motivated and professionally committed to their roles as health care providers.

Their professional commitment was propelled by their aspiration to advance the profession, dedication to student-athletes and athletic training students, and the value they placed on education.

In the health care professions, providers must deliver quality care at all times. In athletic training, however, the demanding work environment can pose challenges in providing care. The collegiate clinical settings possess unique professional challenges to athletic trainers (ATs): for example, long road trips, extended nights away from home, pressure to win, supervision of athletic training students, infrequent days off, high athlete-to-AT ratios, athletes on scholarship, and extended competitive seasons.1–5 These numerous obligations may challenge collegiate ATs' commitments for a prolonged period of time throughout their careers and make it difficult for ATs to remain excited about their role2 and to maintain engagement as health care professionals.

The negative consequences of ATs trying to navigate the demands of their jobs have been well documented. Work-family conflict5,6 and burnout7 encumber an AT's ability to effectively perform the role and develop professionally. Membership statistics from the National Athletic Trainers' Association8 (NATA) suggest a decline in the number of certified members of the athletic training profession between 2001 and 2006.8 Whether this number represents ATs actually leaving the profession or simply a failure to renew membership is unknown. However, it is a troubling trend. Research7 in the early 1990s showed that attrition among ATs was influenced by time commitments, low salaries, and limited advancement. Declining NATA membership in recent years has sparked conversations regarding professional commitment. The positive aspects of the athletic training work setting and individuals' ability to maintain commitment to their professional roles have been examined2 and may offer insights into how to address the high attrition rates in our profession.

Meyer et al9 defined 3 distinct concepts of professional commitment: (1) affective, (2) continuance, and (3) normative. Affective professional commitment refers to identifying with a profession and being loyal and psychologically attached to it. Individuals with strong affective professional commitment remain in the profession because they want to, and they pursue professional development by subscribing to trade journals and attending professional meetings. Normative professional commitment reflects a moral obligation to the profession. Individuals with strong normative commitment remain in a profession because they feel it is simply the right thing to do.9 Continuance professional commitment reflects the perceived costs associated with leaving the profession. Individuals with strong continuance professional commitment remain in the profession because they feel they have more to lose by not doing so. These individuals are less likely to pursue professional development9; they are confined to their roles and do not feel they can leave without negative consequences.10 All 3 components have implications for an individual remaining in or leaving the profession.

Limited research has focused on professional commitment in the context of athletic training. Pitney11 examined professional commitment among ATs working within the secondary school environment and found a strong sense of professional responsibility to both patients and the athletic training discipline. This professional commitment was influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards and respect from others. Winterstein10 concluded that head ATs in the collegiate setting were committed to both the athletic training student and the intercollegiate student-athlete. Although Pitney11 contributed to our knowledge of professional commitment in the secondary school setting and Winterstein10 in the collegiate context among head ATs, the ability of collegiate ATs to maintain commitment to their professional role has not been investigated. Additionally the Winterstein study,10 which was published 16 years ago, sought the perspective of only head ATs. At the end of 2011, 24% of all certified members of the NATA were working in the college/university setting.8 Most of these are employed as assistant or associate ATs and subject to the stressors specific to this setting. Therefore, it is important to examine the professional commitment of the collegiate AT.

The purpose of our study was to examine how ATs working in the collegiate clinical setting identified professional commitment and upheld this commitment in a professionally demanding environment. The central focus of this study was to identify the positive influences affecting professional commitment for ATs working in the collegiate setting. A separate article12 discusses the negative aspects of professional commitment. The following central research questions guided this investigation:

-

1.

How did ATs working in the collegiate setting characterize professional commitment?

-

2.

Which factors positively influenced ATs in upholding their professional commitment over the course of their careers?

METHODS

Our purpose in this exploratory study was to gain a better understanding of professional commitment from ATs employed in the collegiate clinical setting. We used a mixed-methods approach to address the exploratory nature and research questions, as this provides the most flexibility and opportunity. Moreover, the construct of professional commitment can be personal; thus, individual experiences and opinions can vary, which is why qualitative methods are helpful.13 The inclusion of a questionnaire was purposeful to help formalize our findings by uncovering commonalities in our participants' experiences regarding professional commitment through previously validated constructs. Our study was approved by the institutional review board at the host institution before data collection was initiated.

Participants

We used a criterion-sampling strategy13 and initially recruited ATs working full time in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I, II, or III clinical setting. Sampling was purposeful, as our overall aim was to gain a holistic picture of the concerns facing ATs employed in the collegiate clinical setting regarding professional commitment. Data saturation guided recruitment of participants,13 and we believed data saturation was reached after 33 online interviews.

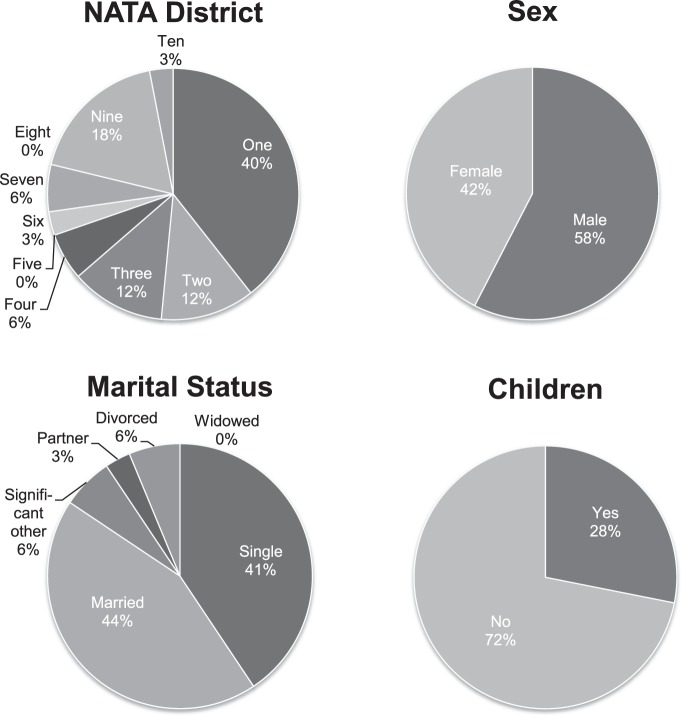

A total of 33 ATs (Division I = 11, Division II = 9, Division III = 13) volunteered for our study. All were certified by the Board of Certification, with an average of 10 ± 8 years of clinical experience. (Mean and standard deviation were rounded to whole numbers.) Participants represented 8 NATA districts; Districts 5 and 8 were not represented. The highest educational level achieved by 29 of the 33 participants was a master's degree. Of the remaining 4 participants, 3 had bachelor's degrees, and 1 had a doctoral degree. The participants' cumulative demographic data (NATA district, marital status, sex, and parental status) are displayed in Figure 1. Individual participants' demographic information (pseudonym, sex, current position, NCAA division, years certified, and educational level) is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Participants' demographic information. Abbreviation: NATA, National Athletic Trainers' Association.

Table 1.

Participants' Demographic Information

| Pseudonym |

Sex |

Current Position |

National Collegiate Athletic Association Division |

National Athletic Trainers' Association District |

Years Certified |

Highest Educational Level |

| Aidan | M | Assistant AT | 3 | 1 | 3 | MS |

| Alisha | F | Head AT | 3 | 1 | 5 | MS |

| Angela | F | Assistant AT | 1 | 2 | 4 | MS |

| Annie | F | Assistant AT | 3 | 1 | 6 | MS |

| Ari | M | Assistant AT | 3 | 1 | 3 | MS |

| Bailey | F | Assistant AT | 1 | 4 | 6 | MS |

| Brandon | M | Head AT | 3 | 1 | 6 | MS |

| Cameron | M | Assistant AT | 1 | 10 | 5 | MS |

| Chris | M | Assistant AT | 1 | 9 | 12 | MS |

| Corey | M | Associate AT | 1 | 2 | 10 | MS |

| Devon | M | Assistant AT | 2 | 7 | 1 | BS |

| Hannah | F | Head AT | 2 | 7 | 7 | MS |

| Ian | M | Assistant AT | 3 | 1 | 4 | BS |

| Jenn | F | Assistant AT | 2 | 6 | 7 | MS |

| Jonah | M | Assistant AT | 2 | 9 | 6 | MS |

| Kaleb | M | Head AT | 3 | 1 | 10 | MS |

| Kristen | F | Assistant AT | 1 | 1 | 7 | MS |

| Maison | M | Assistant AT | 3 | 1 | 4 | MS |

| Martin | M | Head AT | 2 | 1 | 32 | MS |

| Meg | F | Director of sports medicine | 1 | 4 | 25 | PhD |

| Myra | F | Assistant AT | 3 | 1 | 8 | MS |

| Nick | M | Assistant AT | 3 | 9 | 7 | MS |

| Nina | F | Assistant AT | 1 | 2 | 8 | MS |

| Paloma | F | Head AT | 2 | 2 | 7 | MS |

| Ralph | M | Head AT | 3 | 1 | 30 | MS |

| Richard | M | Head AT | 3 | 1 | 32 | BS |

| Scott | M | Head AT | 2 | 9 | 15 | MS |

| Sean | M | Associate AT | 1 | 9 | 9 | MS |

| Seth | M | Head AT | 1 | 3 | 19 | MS |

| Shana | F | Assistant AT | 2 | 9 | 2 | MS |

| Wendy | F | Head AT | 2 | 3 | 7 | MS |

| Whitney | F | Assistant AT | 1 | 3 | 4 | MS |

| Zach | M | Director of sports medicine | 3 | 3 | 7 | MS |

Abbreviations: AT, athletic trainer; BS, bachelor's degree; F, female; M, male; MS, master's degree; PhD, doctoral degree.

Procedures and Data Collection

Participants were recruited via both convenience- and snowball-sampling procedures.13 We sent e-mails to potential recruits requesting voluntary participation in the study. Initially, we capitalized on existing relationships with ATs who fit the inclusion criteria, as well as other contacts in the collegiate clinical setting who were able to connect us with additional recruits. E-mails sent to potential participants contained the study description, including the purpose, the data-collection procedures, the timeline for completion of the study, and the link to the interview questions.

Participants responded to a series of open-ended questions by journaling their thoughts and experiences using QuestionPro (QuestionPro Inc, Seattle, WA). The open-ended questions were based on the research questions and purpose and borrowed from Pitney's11 professional commitment study. The interview guide was reviewed by 3 ATs with qualitative-research experience related to professional socialization and work-life balance for clarity, content, and flow. Based on this review, we made grammatical edits, reworded a few questions, and added questions. Before data collection, the study was piloted with 2 ATs employed in the Division I clinical setting. Minor grammatical and clarification changes were made to the interview guide upon completion of pilot testing.

To fully describe our participants' perceptions of professional commitment, we also used the 6-item, 3-component organizational commitment instrument originally developed by Meyer et al9 and modified by Lee et al14 to ascertain levels of affective, normative, and continuance commitment. These questions were answered via a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scores for each item were summed to obtain a descriptive measure of the level of commitment in each subscale. The possible range of scores in each subscale was 6 to 42.

Data-Analysis and Data-Credibility Procedures

Analysis procedures followed the general inductive process, a conventional method used in health and social science research as described by Thomas15 and Creswell.16 We selected this manner of analysis to help uncover the most dominant themes from the data as they related to the specific aims of the study. Data analysis was guided by the following steps: (1) Open-ended responses were read in their entirety to gain a sense of the data. (2) Scanning of the data continued multiple times; during the third and fourth readings, we began marking key phrases. (3) Significant phrases (meaning units) from each transcript were characterized and coded. (4) Meaning units were positioned into clusters and themes. For a theme to be established, meaning units had to be cited by at least 50% of the study's participants, a strategy used by the author11 of a similar qualitative study.

Multiple-analyst triangulation and peer review were incorporated to ascertain data credibility. The first and second authors (C.M.E., S.M.M.) independently followed the specific steps of the general inductive process. Once we had completed the analysis process, we discussed our findings. During this discussion, we conferred the emergent themes, which included the label assigned and data supporting the emergent theme. Bracketing, consistent with the phenomenologic method, was used.17,18 We identified our own personal beliefs and experiences regarding professional commitment and articulated them in writing to determine if biases entered into the data analysis. It was important to identify our own beliefs to ensure that we were not interpreting the results in a prejudiced manner. Once they were identified, it became clear if these biases entered into the data analysis. Bracketing was helpful in establishing credible results, and we are confident no biases were presented in the final analysis.

We analyzed the quantitative data from the survey using measures of central tendency, specifically means and standard deviations. Separate analyses of variance were used to examine whether a difference existed in the level of commitment across NCAA divisions. This procedure was selected instead of a multivariate analysis of variance because of the positive correlation between affective commitment and normative commitment (r = .61, P < .01). We also conducted a paired-samples t test to determine whether the type of commitment reported by the ATs differed. The a priori α level for all analyses was set at .05.

RESULTS

Quantitative Findings

The measures of central tendencies for the Likert-scale data at each NCAA level are provided in Table 2. Scores did not differ across NCAA divisions for affective commitment (F2,30 = 0.351, P = .71), normative commitment (F2,30 = 0.019, P = .98), or continuance commitment (F2,30 = 1.82, P = .18). However, we found a difference in the participants' total scores for affective and normative commitment (t32 = 4.12, P ≤ .001).

Table 2.

Athletic Trainer Commitment Scores Across National Collegiate Athletic Association Divisionsa

| Commitment Scale |

Score, Mean ± SD |

|||

| Division |

Total |

|||

| I |

II |

III |

||

| Affective | 30.82 ± 5.67 | 29.33 ± 6.38 | 28.38 ± 8.5 | 29.45 ± 7.0 |

| Normative | 24.54 ± 5.89 | 25.22 ± 9.1 | 24.77 ± 8.37 | 24.81 ± 7.61 |

| Continuance | 22.73 ± 8.05 | 27.89 ± 10.7 | 29.15 ± 7.7 | 26.67 ± 8.74 |

Each scale contained 6 questions, which were answered on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scores for each item in the scale were summed and could range from 6 to 42.

Qualitative Findings

Two themes emerged from the inductive-content analysis: (1) professional responsibility and (2) coworker support. Each theme is explained below and supported with quotes from participants, who used pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Professional Responsibility.

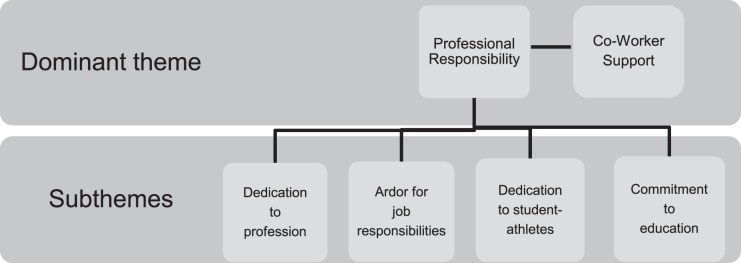

The emergent theme of professional responsibility contained 4 subthemes: (1) dedication to advancing the athletic training profession, (2) ardor for job responsibilities, (3) dedication to the student-athlete, and (4) commitment to education. Figure 2 highlights these emergent subthemes.

Figure 2.

Dominant themes and subthemes describing facilitators of professional commitment for collegiate athletic trainers.

Dedication to Advancing the Athletic Training Profession

Participants explained that a strong commitment to advancing the athletic training profession was a pronounced attribute of their perception of professional commitment. Jenn, a Division II AT, commented, “[Professional commitment means] furthering the profession in regards to respectability among the health care system. Pushing for rights to provide service.” This was echoed by another Division II AT, Paloma, who said that professional commitment means “growth personally and for the profession.” Kaleb, a Division III AT, added, “[Professional commitment is a] dedication to the advancement and continued professionalization of athletic training.” Participants felt a responsibility to act in a way that was representative of the profession and were committed to working in a way that would advance the profession for others. As Ralph stated, “[Professional commitment is] follow[ing] the tenets as set forth by predecessors and peers. Continually put forth effort to expand said tenets to improve the profession so ones who follow are better than you.”

This idea of professional responsibility being directly related to professional commitment was consistently repeated by our participants at all NCAA divisions.

Ardor for Job Responsibilities

Participants were committed not only to advancing the profession but also to fulfilling their job responsibilities. They described their dedication to satisfying the duties required of the profession. As Sean said, “[Professional commitment is] fulfilling the responsibilities of one's hired position and performing the tasks associated with that position and the profession.” Whitney expanded:

Professional commitment means adhering to all the duties described in the job description. Making sure to cover practices, conditioning, [and] lifting sessions. Traveling with assigned teams. Acting as a liaison between parents, athletes, coaching staff, and physicians. Creating rehab programs for injured athletes, including preventative programs.

The ATs' sense of professional commitment and the factors they described as components of their professional responsibilities were influenced by their dedication to their student-athletes, motivation to stay educationally current and share that knowledge with others, and support by their coworkers. These 3 professional responsibilities constitute the remaining emergent themes that help describe the influences of collegiate ATs' professional commitment.

Dedication to Student-Athletes

The participants discussed how the everyday interactions they had with student-athletes helped to maintain their level of commitment. As Corey said, “[I'm motivated by] providing quality care for student-athletes!” This dedication to the student-athlete was seen regardless of division. A Division I AT commented, “I truly enjoy working with the young, college-age[d] student-athlete,” and a Division II AT echoed, “I have a passion for taking care of my athletes.” Dedication to the athletes also appears to be a relevant factor in maintaining motivation; a Division III AT described, “The drive that the athletes have to return to their sport because they love the game and enjoy playing their sport [keeps me motivated and enthusiastic about my work.]”

The intrinsic, derived rewards associated with working with athletes seemed to be significant motivators for many of our participants. As Bailey, a Division I AT, noted, “The simple ‘thank you' from the students after helping them with an injury or problem [keeps me motivated].” The ATs maintained their motivation by taking pride in the relationships and bonds with the student-athletes. For example, Brandon articulated, “I develop strong bonds with the athletes, and you want to see them succeed on the field and in life. I take pride in being a role model to them and I am committed to every one of them.” This concept was reiterated by Bailey, who explained the source of her passion for athletic training:

The kids. It's all about the student-athletes. How we affect and can impact them. Being there for them when they need us physically, mentally, and emotionally. Being somebody who they can rely on and who they turn to for all those little things, as well as the big things. Making their experience as an athlete all it can be. And teaching them how to better take care of themselves and be better people, on and off the field/court/etc.

The ability to create and see a patient's rehabilitation program through to the end specifically provided large intrinsic rewards for our participants. Jenn expressed how the rehabilitation process drives her passion for the profession:

I have a passion for taking care of my athletes, rehabbing them back from postsurgical cases, and seeing them through to the end of an injury. For me, personally, the rehab aspect of the profession is where I get the most fulfillment.

This feeling was also cited by Corey:

[The] majority of my passion is during the rehabilitation phase of athletic training. I am motivated to see the person through [from] day 1 of an injury through a full return to previous or better status.

This ability to work with athletes every day through the rehabilitation process also seemed to reduce the frustration associated with repetitive tasks. This is evident in Aidan's words:

What I enjoy most is that I get to see the results of my work, in the sense that I get to see an individual that I've gone through rehabilitation with return to the field and be able to participate again at a high level. Seeing the end results is an aspect that is unique to athletic training.

Commitment to Education

In addition to being motivated by the student-athlete, collegiate ATs also appear to be motivated by their desire to continue their personal education. One AT said, “[I sustain professional enthusiasm by] attending conferences and trying new things…” Jonah stated that he maintains his level of commitment by “staying up-to-date with the latest techniques.”

This desire to continue their education seems to stem from the desire to provide the best possible care for their athletes: “Continue to expand your own horizons to allow you to better serve your constituents.” As Aidan explained, “I attempt to stay current on the literature and go above and beyond for my athletes whenever possible.” When asked how she maintains her level of commitment, Jenn replied,

I maintain memberships in professional organizations. [I] seek continuing education opportunities. [I] attend conferences annually and I read and seek out changing information on my own, whether through journals or interaction with my peers.

Additionally, the ability to educate athletic training students was described by our participants as a way to maintain professional commitment. As Shana indicated, “Coming in daily, looking to teach those aspiring athletic trainers [keeps me motivated].” Sean attributed his passion to “education of undergraduate athletic training students [and] mentoring undergrad and graduate students.”

This desire to educate seems to tie directly into the professional responsibility of advancing the profession. As Kaleb eloquently said,

My true passion involves educating our future leaders. I have a passion for teaching and learning. While I still enjoy observing an athlete progress from injury to return to play, I have greater satisfaction and pleasure watching students develop their athletic training knowledge and skills.

A commitment to lifelong learning and education of future professionals was a way of fostering professional commitment for the AT.

Coworker Support

The second emergent theme, coworker support, highlights how coworkers positively influence ATs to maintain their professional commitment. It was much easier for our participants to maintain their own professional commitment when they felt their coworkers were committed to the profession. Kristen emphasized, “Having coworkers with the same drive as you makes it easier to maintain what is needed from you professionally.” This was reiterated by Meg, the director of sports medicine in a Division I setting. When asked if coworkers were a factor in her commitment, she answered, “Yes…the people that report to me are very committed to the profession.”

The participants repeatedly talked about how coworkers help sustain their enthusiasm and bring them up when their moods are down. As Devon noted, “We have a laid-back atmosphere, which is enjoyable to work in. Humor is so big here it keeps the mood in good spirits, and when I am down, they pick me up.” This was echoed by Angela: “My coworkers are great examples, and when I am down or having a hard time, have been great influences to help me maintain a professional commitment to my athletes and peers.”

The ability to share work responsibilities was also a positive influence in maintaining professional commitment. Whitney, a Division I AT, explained,

I have great relationships with the other athletic trainers on staff and we are all very supportive of each other. My coworkers and I all help each other out when sports schedules conflict or if we have a personal/family issue to attend to.

Additionally, having coworkers who were invested in education helped to enhance our participants' own professional commitment. Corey was encouraged to learn by coworkers who displayed dedication to learning: “I work with a lot of coworkers who are very good at their job and have a commitment to learn, so I'm partially driven by them.” Shana, employed in the Division II setting, affirmed, “Being able to work together and have a friendly atmosphere really encourages our learning, asking questions, and being able to share things with one another creates a greater professional environment.”

Being surrounded by coworkers who displayed their own commitment, exhibited positive attitudes in the work setting, and fostered an environment of learning all appeared to be positive influences on sustaining one's own professional commitment.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the positive factors that contribute to professional commitment. Our findings revealed that one's sense of professional responsibility and coworker support were factors in commitment. These results expand our understanding of the factors facilitating professional commitment for the AT and illustrate the importance of professional responsibility, collegial interactions, and a healthy workplace environment, which are consistent with reports in the nursing literature19 and the earlier work of Pitney.11

The sense of professional responsibility involved a dedication to the profession and an eagerness to fulfill one's responsibilities and treat patients well. Pitney11 also described professional responsibility and a drive for delivering the highest quality of patient care possible as a cornerstone of an AT's commitment. Winterstein10 identified student-athletes (the primary patients for ATs in the collegiate setting) as the focus of commitment among head ATs in the collegiate setting. We, too, found a dedication to student-athletes among ATs in this study.

In addition, Winterstein10 observed that head ATs were committed to athletic training students, thus emphasizing a focus on education. We also found a focus on athletic training students as a factor contributing to commitment in our sample. Furthermore, our participants attributed their pursuit of continuing education to their professional commitment. Expanding one's knowledge base with continued learning has been identified as a construct of a quality AT20 and plays a role in professional commitment. Pitney11 determined that respect from others was a determinant of professional commitment and that this was achieved by demonstrating competency. Arguably, enhanced knowledge may lead to improved competence and may be a mechanism for gaining respect from others and improving patient care. To that end, continued learning links to the other dimensions of professional responsibility we found.

The dimensions of commitment explained by our participants in their journaling, as well as the Likert-scale data, correspond to affective and normative commitment. The affective and normative dimensions of commitment in the current study are consistent with the results of Winterstein,10 who noted that collegiate head ATs scored higher on affective and normative commitment than on continuance commitment. The affective- and normative-commitment dimensions are particularly relevant when examining retention strategies within an organization because we see that ATs in our study had a desire to remain in the profession. Affective commitment is associated with employee satisfaction, retention, and motivation to contribute to the welfare of the organization.21 Normative commitment is linked with attendance, good behavior, and positive job performance.21 We did, however, observe a difference between the mean affective- and normative-commitment scores, which differed from the findings of Winterstein.10 In our sample, affective commitment was greater than normative commitment, indicating that the participants felt more of an emotional attachment and identification with the organization they worked in than an obligation to stay in the organization.

Affective commitment is associated with being in a professional role; one chooses to do so because involvement produces a satisfying experience.22 For our participants, the satisfying experience was the intrinsic reward they derived from their interactions with the student-athletes. This finding corroborates the idea of receiving intrinsic rewards from interactions with patients as described by Pitney.11 We recommend that a focus on the intrinsic rewards of the athletic training profession be integrated into strategies to improve professional commitment and for collegiate organizations to use to retain ATs. A similar recommendation has been made in support of the retention of nurses.23 Normative commitment is related to a sense of obligation to one's role. The sense of responsibility that our participants felt to the profession and to educating future ATs demonstrated their normative commitment. Comparable with affective commitment, normative commitment develops when an individual encounters positive or satisfying experiences while performing the professional role.

We modeled our study after that of Pitney,11 who examined professional commitment in the secondary school setting. Although he investigated ATs with at least 10 years in the profession, a few of our participants had less experience. Despite data saturation, these less-experienced participants could have had different outlooks once role inductance occurred. Our aim was to examine the professional role commitment of ATs employed in the collegiate setting and not to investigate organizational culture, climate, or justice, all of which may influence an individual's professional role within an organization. Future researchers should look at how these organizational factors may influence an AT's professional commitment. The concept of equity, in particular, has the potential to greatly affect one's professional commitment. Additionally, we garnered information from only 1 point in time. Future authors seeking information on professional commitment should investigate ATs' perceptions of their commitment throughout the year.

CONCLUSIONS

Often, the role of the AT is a thankless one. Our results show that collegiate ATs were internally motivated and professionally committed to their role in the health care profession. Regardless of their NCAA division, collegiate ATs in this study demonstrated professional commitment propelled by their dedication to student-athletes and athletic training students, as well as their aspiration to advance the profession. Maintaining commitment was influenced by a strong sense of coworker support.

Understanding what may positively affect an AT's professional commitment is essential to developing retention strategies and highlighting an organization's influential role in helping ATs maintain their commitment. Implications can be drawn independently from the individual and organizational levels. Individual ATs are encouraged to engage in formal continuing education experiences, such as attending state, district, and national meetings and symposiums. Athletic trainers should ask for support from their employers to attend these in-person sessions, as they provide continued learning, professional rejuvenation, and a way to network. Networking with peers at professional development conferences can create an extended support group for the AT beyond those coworkers they interact with on a daily basis. In turn, employers must support ATs in their pursuit of continuing education by providing time and compensation for the ATs to attend these professional development opportunities. Also, our participants demonstrated a commitment to lifelong learning and being rejuvenated by peers who also enjoyed learning. Athletic trainers seek informal means to learn by collaborating through discourse with their coworkers; thus, it is important for collegiate ATs to continue to engage in learning, which ultimately leads to the development of professional commitment.

More importantly, when seeking employment, ATs must be cognizant of the dynamics among colleagues, as these have the potential to influence professional commitment. Coworker support groups facilitate improved work-life balance and job satisfaction, which are tenets of professional commitment and fundamental to the retention of ATs. Organizationally, supervisors and administrators must be aware of interpersonal relationships among staff members and look for ways to encourage camaraderie, peer learning, and mentoring. Although our participants were internally driven, recognition from their student-athletes was helpful in fostering commitment. Supervisors and administrators must make efforts to recognize and reward their staff members as a way to stimulate and maintain their enthusiasm; gestures as simple as a thank you, a day off, or a monetary reward can be very meaningful.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hendrix AE, Acevedo EO, Hebert E. An examination of stress and burnout in certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35(2):139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malasarn R, Bloom GA, Crumpton R. The development of expert male National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capel SA. Attrition of athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 1990;25(1):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Membership statistics. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. 2014 http://members.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/index.cfm. Accessed July 25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(4):538–551. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winterstein AP. Organizational commitment among intercollegiate head athletic trainers: examining our work environment. J Athl Train. 1998;33(1):54–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitney WA. A qualitative examination of professional role commitment among athletic trainers working in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(2):198–204. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Pitney WA. Athletic trainers' barriers to maintaining professional commitment in the collegiate setting. J Athl Train. 2015;50(5):524–531. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.1.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative Research in Physical Activity and the Health Professions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K, Allen NJ, Meyer JP, Rhee K. The three-component model of organisational commitment: an application to South Korea. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(4):596–614. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas D. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flood A. Understanding phenomenology. Nurse Res. 2010;17(2):7–15. doi: 10.7748/nr2010.01.17.2.7.c7457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer CT. Bracketing in qualitative research: conceptual and practical matters. Psychother Res. 2009;19((4–5)):583–590. doi: 10.1080/10503300902798375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobo VM, Fisher A, Baumann A, Akhtar-Danesh N. Effective retention strategies for midcareer critical care nurses: a Q-method study. Nurs Res. 2012;61(4):300–308. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31825b69b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raab S, Wolfe BD, Gould TE, Piland SG. Characterizations of a quality certified athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2011;46(6):672–679. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.6.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer JP, Allen NJ. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications;; 1997. pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nogueras DJ. Occupational commitment, education, and experience as a predictor of intent to leave the nursing profession. Nurs Econ. 2006;24(2):86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu KY, Lin PL, Wu CM, Hsieh YL, Chang YY. The relationships among turnover intentions, professional commitment, and job satisfaction of hospital nurses. J Prof Nurs. 2002;18(4):214–219. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2002.127573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]