Abstract

Background

People with schizophrenia have significantly raised mortality, but we do not know how their mortality patterns in the UK have changed since the 1990s.

Aims

To measure the 25-year mortality of schizophrenia with particular focus on changes over time.

Method

Prospective record linkage study of the mortality of a community cohort of 370 people with schizophrenia.

Results

The cohort had an all cause standardised mortality ratio of 289 (95% confidence interval 247-337). Most deaths were from the common causes seen in the general population. Unnatural deaths were concentrated in the first five years of follow up. There was an indication that cardiovascular mortality increased relative to the general population (P=0.053) over the course of the study.

Conclusions

People with schizophrenia have a mortality risk that is 2-3 times that of the general population. Most of the extra deaths are from natural causes. The apparent increase in cardiovascular mortality relative to the general population should be of concern to anyone with an interest in mental health.

INTRODUCTION

Mortality is the most robust outcome measure of medical disease and hence a gold standard of clinical performance. It is an important outcome indicator in respect of mental health, where policies and services are judged inter alia by their effectiveness in reducing suicide rates. Unnatural deaths however give only a partial picture of the life expectancy of a vulnerable population. Natural deaths are less dramatic but every bit as final. The excess mortality of people with schizophrenia is a consistent finding in studies of different populations, different continents and different eras1,2,3. The pattern of mortality suggests that the excess unnatural deaths are intrinsic to the disease and the excess natural deaths best explained by altered exposure to environmental risk factors4. Changes in treatment such as the move from asylum to community based services and the introduction of atypical antipsychotic drugs, might be expected to have impacted on the mortality of people with schizophrenia. Evidence from Scandinavia5,6,7 suggests that the mortality of schizophrenia, especially the mortality from cardiovascular disease, increased between the 1970s and the mid 1990s but we do not know if the same trend occurred in the UK. This paper describes the 25 year follow-up of an English community cohort with schizophrenia, recruited in 1981-2. It examines overall mortality and mortality from particular categories and causes of disease as well as changes in mortality over that period.

METHOD

The cohort comprised all Southampton residents aged 16-65, with schizophrenia and living outside hospital, who had contact with the local NHS psychiatric services between 01.02.81 and 31.01.82 (N=370)8. Potential subjects were included if they had: a ‘firm diagnosis of schizophrenia’ made by the responsible consultant, case note evidence of first rank symptoms of schizophrenia or persistent non-affective delusions or auditory hallucinations, in the absence of organic brain disease, abuse of alcohol or other substance.

An analysis of the cohort up to 31.12.1994 was reported previously9. Using identical methodology, we now present an analysis of the follow-up to 31.08.2006, the midpoint of the twenty-fifth year following recruitment. Subjects were classified as alive, dead or untraced, based on the database of the Office of National Statistics (ONS)10. Vital status was then checked through Hampshire Partnership NHS Trust case notes, GP or mental health worker. Subjects were classified as alive if there was independent confirmation of contact since the census date. Death was confirmed by death certificate or other official document. Subjects were otherwise classified as untraced and were included in the follow-up analysis until the date they were lost. The study had ethics approval from the Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics committee.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The person-years-at-risk were calculated according to the following variables: calendar year (1981-2006), sex, age category (15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40-44, 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, 65-69, 70-74, 75-79, 80-84, and ≥85 years). The person-years-at-risk were then multiplied by the corresponding mortality rates for England and Wales10, thus producing the expected number of deaths for each year / sex / age-specific stratum.

The standardised mortality ratio (SMR) was obtained by dividing the number of deaths observed by the number of deaths expected, and multiplying this ratio by 100. An increased SMR is statistically significantly elevated at the 5% level of significance when the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) is greater than 10011.

SMRs were calculated for all causes, for particular ICD12,13 categories of disease and for specific diseases where more than two deaths were observed.. The change in SMR over the study period, was analysed by computing SMRs for each five years of follow-up. Comparisons between SMRs and tests for trend were performed using Poisson regression. Poisson regression was also used to explore internal relationships in the data independent of the national population rates.

RESULTS

All cause mortality (ICD-9 001-999, ICD-10 A01-Y99)

The cohort comprised 213 males and 157 females at recruitment. The vital status of 363 (98%) subjects was established on the census date (31.08.2006). One hundred and ninety three were confirmed to be alive, six were recorded as alive on the ONS database but not independently confirmed, seven were untraced and 164 deaths were recorded. Of these deaths 141 were due to natural causes and 21 to unnatural causes. Two deaths were from unknown causes; one abroad and one where the death certificate could not be traced.

The mean age at death of males was significantly lower than that of the females (57.3 years vs 65.5 years, t=4.3, df=162, P<0.001). This difference remained when unnatural deaths were excluded from the analysis (males 60.4 years vs females 67.3 years, t=4.2, df=139, P<0.001). The all cause SMR was 289 (95% CI 247-337), a three-fold increase in mortality compared with the population of England and Wales (Table 1). Approximately 81% of the excess mortality was due to deaths from natural causes and 17% to deaths from unnatural causes (2% of deaths were undetermined). The all-cause SMR was higher in males, the unemployed, unmarried and patients from lower social classes but none of these differences were statistically significant The internal analysis showed that all cause mortality was higher in males than females but there were no statistically significances when examining unemployment, marital status and social class.

Table 1.

Mortality between 1981 and 2006 of a community cohort of 370 people with schizophrenia, by category of disease (ICD-91 and ICD-102), showing observed deaths, SMRs and 95% CIs, by gender, for those disease categories where there were five or more deaths.

| Cause of death (ICD-9, ICD-10) | Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | SMR (95% CI) | Observed | SMR (95% CI) | Observed | SMR (95% CI) | |

| Neoplasms (140-239, C00-D48) | 20 | 193 (118-298) | 10 | 102 (49-188) | 30 | 149 (100-212) |

| Endocrine disease (420-297, E00-E99) | 2 | 443 (54-1601) | 5 | 1184 (384-2763) | 7 | 801 (322-1651) |

| Nervous diseases (320-389, G00-G99) | 3 | 498 (103-1456) | 2 | 352 (43-1270) | 5 | 427 (139-996) |

| Circulatory diseases (390-459, I00-I99) | 35 | 269 (187-374) | 22 | 241 (151-365) | 57 | 258 (195-334) |

| Respiratory diseases3 (460-519, J00-J99) | 7 | 270 (108-556) | 19 | 726 (437-1133) | 26 | 499 (326-731) |

| Digestive diseases (520-579, K00-K99) | 4 | 298 (81-764) | 3 | 278 (57-812) | 7 | 289 (116-596) |

| Natural deaths (0-799, A00-R99) | 76 | 258 (203-323) | 65 | 262 (202-334) | 141 | 260 (219-306) |

| Unnatural deaths (E800-999, V00-Y99) | 14 | 775 (424-1300) | 7 | 1071 (431-2207) | 21 | 854 (529-1305) |

| All causes (0-999, A00-Y99) | 92 | 294 (237-361) | 72 | 283 (221-356) | 164 | 289 (247-337) |

World Health Organisation, 1977.

World Health Organisation, 2007.

P-value for difference between SMRs for males and females = 0.03

Cause of death

The SMR was increased in most major disease categories (Table 1) but is only presented for disease categories where more than five deaths were reported. Individual categories showed apparent gender differences but only that for respiratory diseases was statistically significant (P=0.03). The most significant contributions to the overall excess mortality came from circulatory diseases (ICD-9 390-459, ICD-10 I00-I99) which accounted for 33% and respiratory diseases (ICD-9 460-519, ICD-10 J00-J99) which accounted for a further 19%.

We also examined specific causes of death where the numbers exceeded two. Of thirty cancer deaths thirteen were from lung cancer (SMR 265, 95% CI 141-453), four from female breast cancer (SMR196, 95% CI 54 to 503), the rest spread across a range of other sites. The SMRs from suicide, diabetes, pneumonia and chronic obstructive airways disease were strikingly elevated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mortality between 1981 and 2006 of a community cohort of 370 people with schizophrenia, by cause of death (ICD-91 and ICD-102), showing observed deaths, SMRs and 95% CIs, for those diseases where there were three or more deaths.

| Cause of death | ICD-91 | ICD-102 | Observed | SMR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | 162 | C33-C34 | 13 | 265 (141-453) |

| Breast cancer (females) | 174 | C50 | 4 | 196 (54-503) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250 | E10-E14 | 4 | 614 (167-1573) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 390-429 | I00-I52 | 37 | 225 (159-311) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 430-438 | I60-I69 | 13 | 308 (164-527) |

| Pneumonia | 480-487 | J09-J18 | 15 | 835 467-1377 |

| Chronic obstructive airways disease | 490-494, 496 | J40-J47 | 11 | 394 197-705 |

| Accident | E800-949 | V01-X59 | 4 | 307 (84-786) |

| Suicide | E950-959 | X60-X84 | 14 | 1818 (994-3051) |

| Undetermined | E980-989 | Y10-Y34 | 3 | 928 (191-2713) |

World Health Organisation, 1977.

World Health Organisation, 2007.

Smoking related mortality

Seventy three per cent (224) of the cohort, for whom smoking status was recorded (N= 306), were cigarette smokers at the outset of the study. This was more than twice the contemporary general population prevalence (35%)15. The SMR among cigarette smokers was significantly higher than among non-smokers (379; 95% CI 311-459 vs 194; 95% CI 125-286, P=0.002) and the internal analysis showed that mortality in smokers was more than double that in non-smokers (relative risk = 2.16, 95%CI: 1.31 to 3.59). Ninety five deaths were from diseases caused by cigarette smoking15, an SMR of 275 (95% CI 222-336). Smoking related diseases accounted for 70% of the excess natural mortality in the cohort.

Time trends in mortality

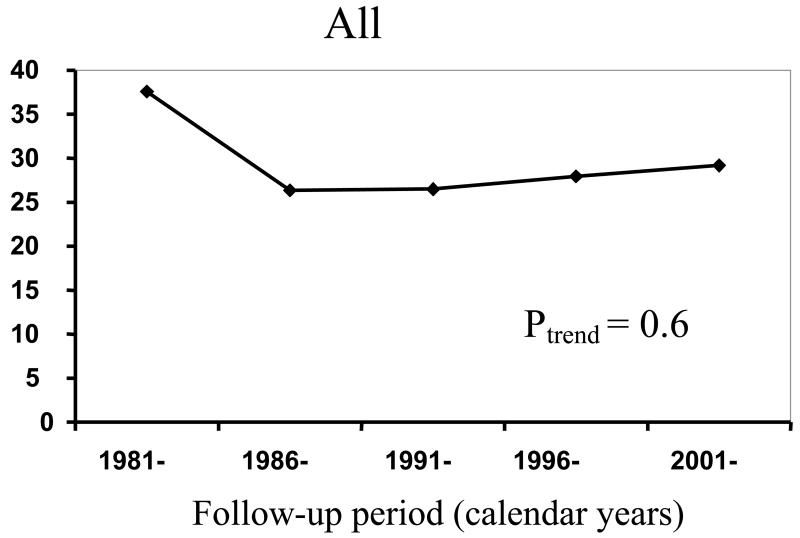

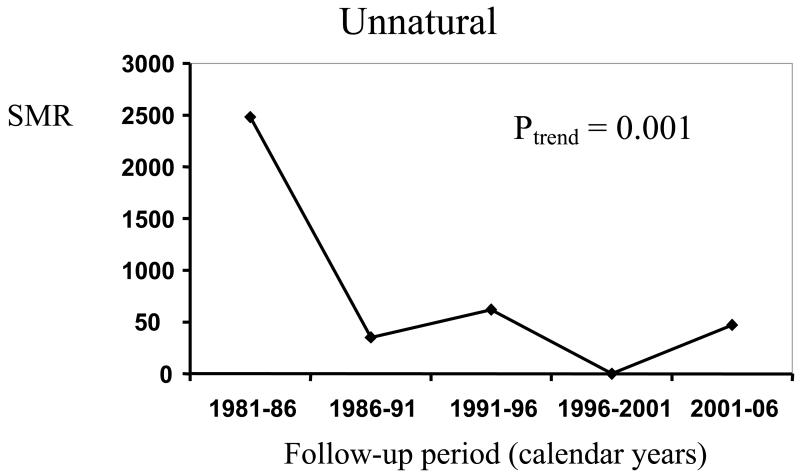

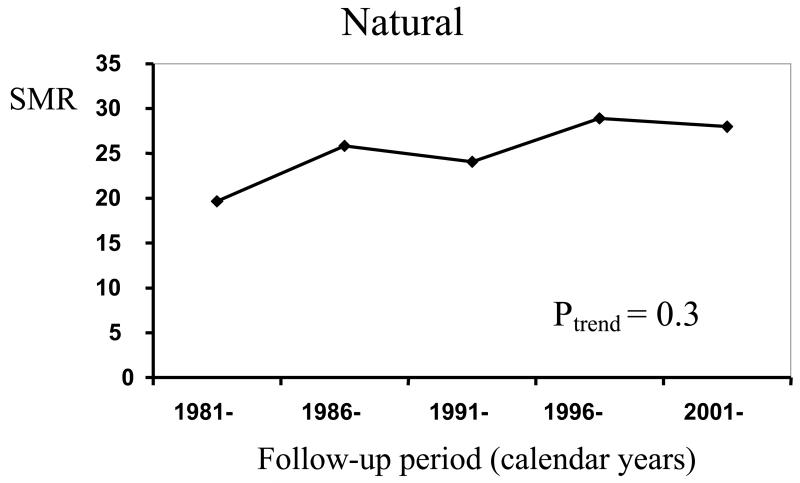

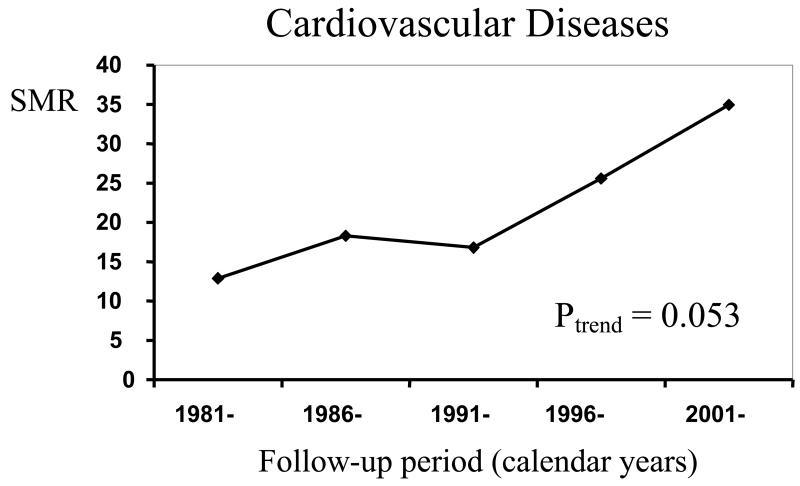

Table 3 and Figures 1-4 show the time trends in mortality from all causes and various major disease categories. The all-cause SMR showed small but non-significant changes between 1981 and 2006, falling in the first five years then rising slightly from 264 (95%CI 174-384) in 1986-91 to 292 (95% CI 212-392) in 2001-6 (P=0.6). This was produced by the aggregate effect of a non-significant (P=0.3) increase in natural cause SMR between 1981-6 and 2001-6 from 196 (95% CI 105-336) to 280 (95%CI 201-380) and a large and statistically significant (P=0.001) fall in unnatural SMR from 2482 (95%CI 1357-4164) to 472 (95%CI 57-1705) over the same time period (Table 3). The excess unnatural cause SMR was largely due to suicide (Table 2), which fell significantly (P=0.002) over time. The internal analysis also revealed significant negative trends with time for suicide and unnatural deaths (P=0.002 for both causes)

Table 3.

Cause of death of 164 patients with schizophrenia with observed deaths (in brackets and italics), SMRs and 95% CI (in brackets), for each five-years of follow-up, for those disease categories where more than ten deaths were reported.

| Cause of death (ICD-9, ICD-10) | SMR (Observed) | χ2 test for SMR time-trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | ||||||

| Follow-up period (calendar years) | ||||||

| 1981-86 | 1986-91 | 1991-96 | 1996-2001 | 2001-06 | ||

| Neoplasms | 157 (4) | 161 (6) | 142 (6) | 138 (6) | 150 (8) | P = 0.9 |

| (140-239, C00-D48) | (43-401) | (59-351) | (52-309) | (50-299) | (65-296) | |

| Circulatory diseases | 136 (4) | 261 (11) | 275 (13) | 228 (11) | 332 (18) | P = 0.2 |

| (390-459, I00-I99) | (37-348) | (130-466) | (146-470) | (114-408) | (197-525) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 129 (3) | 183 (6) | 168 (6) | 256 (9) | 350 (13) | P =0.053 |

| (390-429, I00-I52) | (27-377) | (67-398) | (62-366) | (117-485) | (186-598) | |

| Respiratory disease | 435 (2) | 0 (0) | 491 (5) | 907 (13) | 367 (6) | P = 0.4 |

| (460-519, J00-J99) | (53-1571) | (0-552) | (160-1147) | (483-1552) | (135-798) | |

| Suicide | 6110 (12) | 0 (0) | 1276 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | P=0.002 |

| (E950-959, X60-X84) | (3157-10673) | (0-1981) | (154-4608) | (0-3041) | (0-3380) | |

| Natural deaths | 196 (13) | 259 (25) | 241 (27) | 289 (35) | 280 (41) | P = 0.3 |

| (0-799, A00-R99) | (105-336) | (167-382) | (159-350) | (201-402) | (201-380) | |

| Unnatural deaths | 2482 (14) | 352 (2) | 620 (3) | 0 (0) | 472 (2) | P=0.001 |

| (E800-999, V00-Y99) | (1357-4164) | (43-1270) | (128-1812) | (0-880) | (57-1705) | |

| All causes | 376 (27) | 264 (27) | 265 (31) | 279 (35) | 292 (44) | P = 0.6 |

| (0-999, A00-Y99) | (248-547) | (174-384) | (180-376) | (195-388) | (212-392) | |

World Health Organisation, 1977.

World Health Organisation, 2007.

Figure 1.

Changes in all cause SMR in five year periods of a community cohort of 370 people followed over 25 years

Figure 2.

Changes in unnatural SMR in five year periods of a community cohort of 370 people followed over 25 years

Figure 3.

Changes in natural SMR in five year periods of a community cohort of 370 people followed over 25 years

Figure 4.

Changes in cardiovascular SMR in five year periods of a community cohort of 370 people followed over 25 years

The SMR for cardiovascular diseases increased over the study period a, from 129 (95%CI 27-377) in 1981-5 to 350 (95%CI 186-598) in 2001-6. This trend was of borderline statistical significance (P=0.053). The internal analysis however showed no significant trend for this cause (P=0.3) although, using the period 1991-1996 as the baseline, the relative risks rose monotonically from 0.76 (95%CI 0.19-3.12) for 1981-86 to 1.52 (95%CI 0.57-4.07) for 2001-6. There were no consistent trends in the other disease categories where more than ten deaths were observed either examining the SMRs or using an internal analysis.

DISCUSSION

These results support previous findings that people with schizophrenia have a mortality of between two and three times that of the general population and that most of the excess deaths are from diseases that are the major causes of death in the general population. They indicate that the increased mortality risk is probably lifelong and suggest that the cardiovascular mortality of schizophrenia has increased over the past twenty five years relative to the general population. A large part of the excess mortality can probably be attributed to the effects of cigarette smoking.

Strengths and weaknesses

The recruitment process missed people with unrecognised schizophrenia and those who avoided service contact during the index year but was representative of Southampton residents with schizophrenia living outside hospital and known to local mental health services in 1981-2. People living in the local long stay hospital and those with a concurrent diagnosis of substance misuse were deliberately excluded, to yield a community cohort of people with uncomplicated disease8. The Southampton mental health services were typical of contemporary services hence the cohort is probably representative of people with schizophrenia who were engaged with mental health services in the early 1980s. The use of a cohort recruited twenty five years ago inevitably means that the experience described here may differ from that of more recently diagnosed patients.

Ascertainment was more rigorous than in most comparable studies as status was independently checked. Loss to follow up was small and comparable to that in similar recent studies. Death certificates were matched to NHS central records, using family and given name, date and place of birth, place of death and NHS number where known. The death certificate causes of death are probably more accurate than in the general population, because rates of post mortem examination (54% vs 22%), and coroner’s inquest (15% vs 6%) were higher than the national average16. Schizophrenia was mentioned as a contributory cause of death on nine (5%) certificates.

The strengths of this study are the longest follow up period of recent studies of schizophrenia mortality, the completeness of follow up and the cross checking of status. The main weaknesses are the use of a relatively small local cohort which may limit generalisation and the use of a prevalence rather than an incidence cohort. This meant that all but 27 subjects had already survived the period of greatest excess mortality at recruitment, an issue which is probably more relevant to unnatural mortality, which is concentrated early in the disease17, than to natural mortality. The exclusion of people with co-morbid substance misuse probably produced an underestimate of excess mortality.

All cause mortality

The all cause, natural and unnatural cause SMRs are broadly consistent with comparable recent studies, which suggested that schizophrenia is associated with a two to three fold increase in mortality, with a large relative excess mortality from unnatural causes amongst younger patients and a less dramatic but numerically greater excess mortality from natural causes amongst patients in middle or older age1,2,3.

Change in mortality with length of follow up

Previous studies of schizophrenia mortality, both meta-analysis1,3 and large individual cohort studies18, suggested with one exception19, that all cause SMR falls with increasing age and with length of follow up. A very large Scandinavian cohort study found a significant but only very slightly elevated SMR in older patients with chronic schizophrenia20. This pattern is largely because the suicide SMR is highest in young patients early in the disease process17, 18, when a small number of suicides produce a large overall SMR, probably the most significant process in shorter follow up studies. The only study that specifically examined natural cause SMR found no clear relationship between length of follow up and the SMR for natural causes and an inverse relationship between length of follow up and cardiovascular SMR18. The present finding that natural mortality increased and cardiovascular SMR increased significantly with length of follow up contradicts previous findings and supports the hypothesis that the cardiovascular mortality of schizophrenia is increasing.

Change in mortality in successive time periods

Evaluating apparent time changes in the mortality of a particular disease is complex. Differences in mortality in successive cohorts may be caused by confounding variables. Changes in mortality of an individual cohort may not generalise to other cohorts. Meta-analysis is susceptible to confounding by the inclusion of heterogeneous studies. One meta-analysis suggests that the all cause mortality SMR in those with schizophrenia increased3 between the 1970s and the 1990s, a second suggests that it did not1. One large Scandinavian record linkage study found dramatic increases in all cause mortality in successive cohorts with schizophrenia5 while another found an increase in suicide SMR but no time trend in natural mortality18. Other Scandinavian studies found no significant time trends in mortality over the same time period21, 22. The present study supports findings from Ösby et al’s large Swedish study that the natural cause mortality and especially the cardiovascular mortality of schizophrenia is increasing5, a finding that should be of serious concern to mental health clinicians and service planners.

We cannot be sure whether the absolute cardiovascular mortality of schizophrenia increased over the study period. Changes in SMR may be due to increased cohort mortality, decreased general population mortality or some combination of these two trends. The absolute cardiovascular mortality of the present cohort increased over the course of study but this would be expected as the cohort itself aged. The annual UK mortality from ischaemic heart disease fell from 36 to 19/10,000 population (males) and 16 to 9/10,000 population (females) between 1982 and 200023. This was incorporated into the calculation of expected deaths but contributes to the rise in cohort cardiovascular SMR. The situation has some uncomfortable parallels with the 1920s when public health measures reduced TB mortality in the general population a good decade earlier than among asylum patients24.

A twin study4 suggested that variations in the natural mortality in schizophrenia are best explained by altered patterns of exposure to environmental risk factors. The most significant cardiovascular risk factor in the general population is cigarette smoking15. This fell in the UK general population from 39% in 1980 to 25% in 200415 but did not fall in people with schizophrenia; the 1996 prevalence of cigarette smoking in a subgroup (N=102) of the present cohort was 66%25 and the prevalence in a similar 2003 Scottish cohort 70%26. Changes in the patterns of cigarette smoking are calculated to account for 36% of the fall in Scottish cardiovascular mortality between 1975 and 199427. It is therefore likely that the continued high rates of cigarette smoking explains much of the excess cardiovascular (and indeed other) mortality of the present cohort. Reducing smoking related mortality will require the delivery of effective anti-smoking strategies. At the present time there is evidence that individuals with schizophrenia can stop smoking with appropriate help28 but no evidence that these interventions have detectable benefits for the population with schizophrenia.

Other relevant risk factors include diet, exercise, obesity, relative poverty and poor health care26, many of which are inter-related. The present study does not address the impact of the atypical antipsychotic drugs but there are theoretical reasons for concern about their cardiovascular risk29. In this context it is interesting (but far from conclusive) to note that the introduction of these drugs (risperidone in 1993, olanzapine in 1996 and quetiapine in 1997) coincided with the steepest rise in cardiovascular mortality in the present study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that the natural cause mortality of schizophrenia is increasing, a finding that must be of concern to everyone involved with this disease. Further large-scale long term follow-up studies are needed to establish the reasons behind this increase and to suggest useful interventions. In the meantime the most clinically useful intervention is probably to try and help patients with schizophrenia to stop smoking.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of James and Jane Gibbons who established the original database and of Brian Barraclough who suggested, supported and encouraged this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None. Most of the data collection and analysis was done by CM and ML as part of respective University degree courses.

Contributor Information

Steve Brown, Hampshire Partnership NHS Trust.

Miranda Kim, MRC Epidemiology Resource Centre, University of Southampton.

Clemence Mitchell, University of Southampton.

Hazel Inskip, MRC Epidemiology Resource Centre, University of Southampton.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris E, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia. Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendler K. A twin study of mortality in schizophrenia and neurosis. Archives of General Psychiatr. 1986;43:643–649. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800070029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ösby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparén P. Time trends in schizophrenia mortality in Stockholm County Sweden: cohort study. BMJ. 2000;321:483–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen V, Jacobsen B, Arnesen E. Cause-specific mortality in psychiatric patients after deinstitutionalisation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:438–443. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munk-Jørgensen P, Mortensen P. Incidence and other aspects of the epidemiology of schizophrenia in Denmark, 1971-87. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:489–495. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbons J, Horn S, Powell J, Gibbons J. Schizophrenia patients and their families. A survey in a psychiatric service based on a DGH unit. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:70–77. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office for National Statistics Annual mortality statistics. 2008 Available from www.ons.gov.uk.

- 11.Gardner M, Altman D. Statistics with confidence. British Medical Journal. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation . Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death. World Health Organisation; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organisation . International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, Version for 2007. World Health Organisation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslow N, Day N. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol. II. The design and analysis of cohort studies. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Information Centre . Statistics on smoking: England 2006. The Information Centre; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Justice . Statistics on deaths reported to coroners England and Wales, 2007. Ministry of Justice; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inskip H, Harris E, Barraclough B. Lifetime risk of suicide for affective disorder, alcoholism and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:35–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortensen P, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in first admitted schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:183–189. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence D, Jablensky A, Holman C, Pinder T. Mortality in Western Australian psychiatric patients. Soc Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:341–347. doi: 10.1007/s001270050248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mortensen P, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenic patients in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81:372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salokangas R, Honkonen T, Stengård E, Koiviston A. Mortality in chronic schizophrenia during decreasing number of psychiatric beds in Finland. Schizophr Res. 2002;54:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heilå H, Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Lönnquist J. Mortality among patients with schizophrenia and reduced hospital care. Psychol Med. 2005;35:725–732. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Office of National Statistics . 20th century mortality trends in England and Wales. Office of National Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ødegård Ø . The excess mortality of the insane. Acta Psychiatr et Neurolog Scand. 1952;27:353–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thomson C. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1999;29:697–701. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCreadie R. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: Descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:534–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capewell C, Morrison C, McMurray J. Contribution of modern cardiovascular treatment and risk factor changes to the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in Scotland between 1975 and 1994. Heart. 1999;81:380–386. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campion J, Checinski K, Nurse J. Review of smoking cessation treatments for people with mental illness. Advan Psychiatr Treat. 2008;14:208–216. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melkersson K, Dahl M. Adverse Metabolic Effects Associated with Atypical Antipsychotics: Literature Review and Clinical Implications. Drugs. 2004;64:701–723. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]