Abstract

Background:

Optimal aesthetic outcomes from rhinoplasty are heavily influenced by structures adjacent to the nose. Although the importance of the chin has been emphasized since the inception of rhinoplasty, little attention has been given to the forehead. The forehead/glabella/radix complex represents a vital triad in rhinoplasty, from which the nasofrontal angle is derived. In the present study, the authors sought to determine whether fat grafting to the forehead/glabella/radix complex and pyriform aperture can favorably impact the nasofrontal and nasolabial angles, respectively.

Methods:

The authors reviewed pre- and postoperative images (obtained by an independent professional photographer) of patients who underwent autologous fat grafting to the forehead/glabella/radix region and the pyriform aperture, with or without concurrent rhinoplasty. Nasofrontal and nasolabial angles were measured on lateral images. Mean pre- and postoperative values were calculated and compared. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

Twenty-six patients underwent fat grafting alone (FG group; mean follow-up, 3.3 years), and 19 had fat grafting plus rhinoplasty (FG + R group; mean follow-up, 5.2 years). The mean nasofrontal angle in the FG group decreased by 2.0° (P = 0.005), and the mean nasolabial angle increased by 2.3° (P = 0.006). The mean nasofrontal angle in the FG + R group decreased by 2.0° (P = 0.011), and the mean nasolabial angle increased by 6.0° (P = 0.026).

Conclusions:

Autologous fat grafting to the forehead/glabella/radix complex and pyriform aperture is a reliable method to favorably influence the nasofrontal and nasolabial angles, respectively. Such treatment optimizes the interplay between the nose and the adjacent facial features, enhancing overall aesthetics.

Rhinoplasty began as an operation of the nasal profile, with particular emphasis on nasal reduction and reshaping.1 Aufricht2 was one of the first rhinoplasty surgeons to describe the significance of facial features adjacent to the nose, particularly the interplay between the nose and the chin. He described nasal hump reduction and “transplantation” of the osteocartilaginous segment to the chin as a treatment for microgenia.

Unlike the chin, the forehead has received little or no attention in relation to the nose. According to Ousterhout,3 the forehead functions to convey beauty, strength, feelings of intelligence, and various emotions. Methods to alter its contour include bony advancement, bone grafts, Silastic implants (Dow Corning, Midland, Mich.), and methyl methacrylate, his method of choice (at the time of publication). An internet search of “forehead augmentation” yielded only a few results for forehead augmentation with fat or methyl methacrylate, all of which were Asian cosmetic sites,4–6 and none of them mentioned the influence of the forehead on the nose. Only recently (September 2014), in a review of forehead rejuvenation, was forehead contour mentioned along with more standard techniques.7

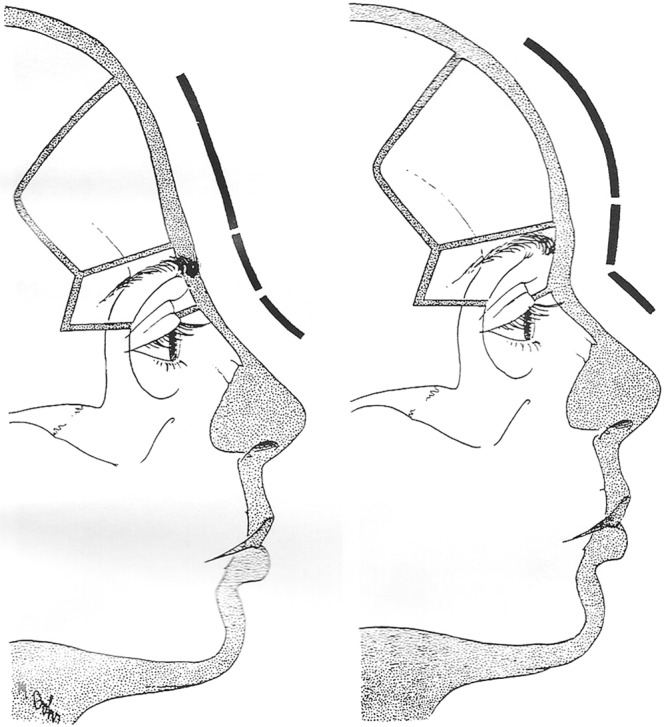

Anatomically, the forehead comprises 2 components, the upper forehead and the supraorbital bar, which contribute to the nasofrontal angle (Fig. 1).3 The forehead, glabella, and radix represent a critical triad in aesthetic rhinoplasty, forming the nasofrontal angle. This relationship is similar to the interplay between the upper lip, the columella, and the nasal tip, reflecting the nasolabial angle.

Fig. 1.

The upper forehead and the supraorbital bar contribute to the nasofrontal angle. Reprinted with permission from Ousterhout DK, ed. Aesthetic Contouring of the Craniofacial Skeleton. 1st ed. San Francisco, Calif.: Little, Brown and Co; 1991.3

Autologous fat grafting to the face is growing in popularity and is currently regarded as a reliable and efficacious procedure.8,9 It is being used increasingly to revolumize the aging face, as a stand-alone treatment or in conjunction with surgical procedures such as facelifts and rhinoplasties performed by the senior author (A.N.K.). Facial atrophy, including soft tissues and skeletal remodeling, directly influence both the nasofrontal and nasolabial angles.10–12 From the senior author’s 20-year experience with this procedure, he believes (as do many of his patients) that successful fat grafting may help control ongoing facial atrophy in addition to remedying the contour issues associated with aging.13,14 With respect to age-related bone atrophy, the senior author posits that it results from progressive diminution of blood supply. Vascular growth factors in successfully grafted fat cells are able to retard ongoing bone loss.

In the present study, the authors examined whether fat grafting to the forehead, glabella, and radix complex can provide control of the nasofrontal angle and, similarly, if fat grafting to the pyriform aperture can favorably influence the nasolabial angle. The study population included patients who underwent fat grafting alone (FG group) and patients who underwent it in conjunction with rhinoplasty (FG + R group). In all cases, the procedures were performed to address aesthetic concerns that included the appearance of the nose.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

A level III retrospective review was performed of independently obtained professional photographs of consecutive patients who underwent fat grafting to the forehead/glabella/radix complex and the pyriform aperture, with or without concomitant rhinoplasty. All procedures were performed by the senior author (A.N.K.). Eligible participants were required to have both pre- and postoperative professional clinical photographs. Patients who had undergone rhinoplasty previously or had received prior injections of dermal fillers or botulinum toxin A were excluded from the analysis. Written informed consent was provided by all study patients after the risks and benefits of the procedures had been discussed thoroughly with them.

Review of Photographs

All photographs originated from a prospectively maintained database owned by the senior author (A.N.K.). Pre- and posttreatment frontal and lateral images of eligible patients were evaluated. Data collected during the review included patient age, gender, follow-up interval, quantity of grafted fat, and measurements of nasofrontal and nasolabial angles (obtained from the photographs). Measurements were expressed in degrees.

Measurement of Nasofrontal Angles

The radix was marked on right-sided lateral photographs. Lines were drawn using a digital protractor to the junction of the forehead and the nasal dorsum. If a deep radix was present, the protracted lines were set to a point just anterior to the radix to facilitate accurate measurement of the angle. Angles were measured using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (San Jose, Calif.) and documented.

Measurement of Nasolabial Angles

The junction of the upper lip and the columella was marked on right-sided lateral photographs. Lines were drawn using a digital protractor to the upper lip and columellar-lobule junction. If this junction was curvilinear, a point was made on the midpoint of the curve. Angle measurements were documented.

Surgical Techniques

Fat Harvesting and Injection

Donor sites were infiltrated with tumescent solution (1 cm3 to 1 cm3 for expected volume of fat harvested), and fat was harvested using a 3-mm Luer-lock cannula under low pressure in 10-cm3 syringes. Fat was then collected in 10-cm3 syringes, and oil and serum were decanted before centrifugation. The harvested fat samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 2–4 minutes, depending on the tissue turgor of the specimens. The goal was to obtain a homogeneous “paste” that could be easily and predictably injected. The oil and serum were again fractionated and decanted.

Viable fat cells were placed in 1-cm3 syringes in preparation for injection. The fat type of each patient was assessed before injection. Less fibrous fat has better flow characteristics, permitting smoother infiltration. It is important to be cognizant of the flow characteristics of the fat being injected to prevent irregularities and to ensure that specimens of similar quality are used symmetrically.

Attention was then focused on the recipient sites of the face. No incisions were made; instead, a 16-gauge needle was used to provide cannula access. Then, small aliquots of fat were injected through a 17-gauge side port bullet-tip cannula (Grams Medical, Costa Mesa, Calif.). The tip of the cannula was placed to a depth until bone was palpated. Fat was injected in tiny aliquots to maintain intimate contact with adequate vascular supply, similar to skin grafting. Digital control of aliquot dispersion and minimizing side-to-side sweeping of the cannula (which can produce local tissue trauma) are important for achieving optimal results.

The initial injections were administered in the deep compartments, preperiosteally, with careful attention to local skin turgor. If skin laxity and contour were not addressed sufficiently, the injection proceeded superficially. It is imperative to constantly reevaluate the global aesthetics of the face during the injection process to ensure blending of the forehead and the nose and of the upper lip and nasal base. Any lumps that might have remained after injection were aspirated with the 19-gauge injection cannula.

The amount of fat injected varies according to the site itself and the goals of the patient and surgeon. Approximately 20 cm3 of fat was injected into the lower forehead and nasofrontal region until the aesthetic endpoint of a lateral-to-lateral and cranial-to-caudal gentle convexity was achieved.

Rhinoplasty

Standard rhinoplasty techniques were performed as dictated by preoperative and intraoperative evaluation and until the senior author was satisfied with the result in the operating room.

Comparisons and Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postoperative nasofrontal and nasolabial angles were compared within the FG and FG + R groups. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test and SPSS Statistics software (version 21 for Mac; IBM, Armonk, N.Y.) were used to compare pre- and posttreatment measurements. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Each study group was analyzed separately. As noted earlier, the FG group underwent fat grafting to the nasofrontal and pyriform regions alone, and the FG + R group received fat grafting to the same regions in conjunction with rhinoplasty. The FG group comprised 24 women and 2 men, with a mean age of 44.15 years (range, 23–60 years) and mean follow-up period of 3.3 years (range, 0.64–9.1 years). The FG + R group consisted of 17 women and 2 men, with a mean age of 39.10 years (range, 27–63 years) and mean follow-up time of 5.2 years (range, 0.28–11.4 years).

Postoperative measurements of both angles were collected during follow-up visits. Data from the most recent follow-up visit are presented herein. Throughout the follow-up period, no patient in either study group received additional fat grafting to these regions.

Postoperative Measurements

FG Group (n = 26)

The average volumes of injected fat were 19.60 cm3 to the nasofrontal region and 11.61 cm3 to the pyriform region.

The mean nasofrontal angle was 136.7° before treatment and 134.7° after treatment (Table 1). The difference between the mean values was 2.0° (P = 0.005).

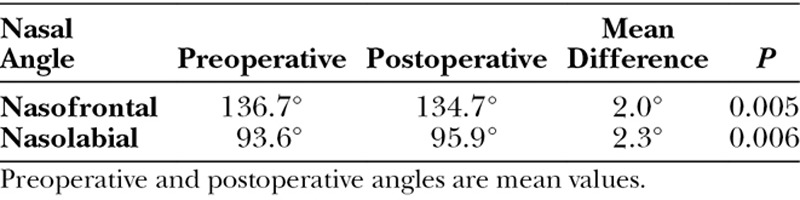

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for Patients Who Underwent Fat Grafting Alone (FG Group)

The mean nasolabial angle in this group was 93.6° before treatment and 95.9° after treatment. The difference between the mean values was 2.3° (P = 0.006).

FG + R Group (n = 19)

The average volumes of injected fat were 13.94 cm3 to the nasofrontal region and 12.36 cm3 to the pyriform region.

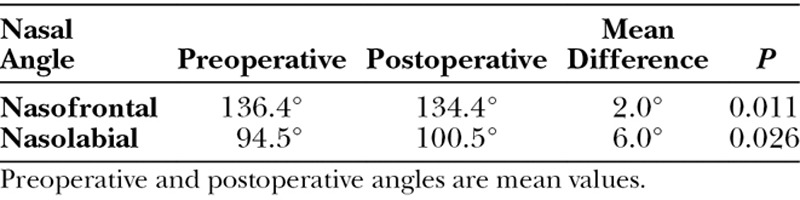

The mean nasofrontal angle was 136.4° preoperatively and 134.4° postoperatively (Table 2). The difference between the mean values was 2.0° (P = 0.011).

Table 2.

Descriptive Data for Patients Who Underwent Fat Grafting + Rhinoplasty (FG + R Group)

The mean nasolabial angle was 94.5° preoperatively and 100.5° postoperatively. The difference between the mean values was 6.0° (P = 0.026).

No complications occurred in either group. Long-term fat retention throughout the follow-up period was ≥80% in all patients. Visual and digital examination revealed smooth forehead contour in all cases. Representative before-and-after clinical photographs are shown in Figures 2–5.

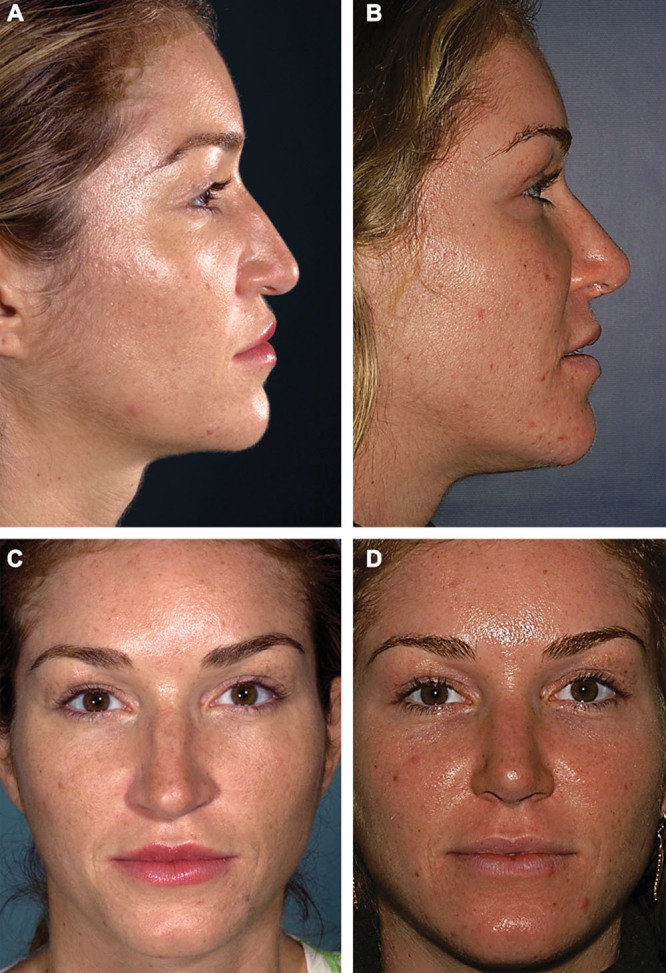

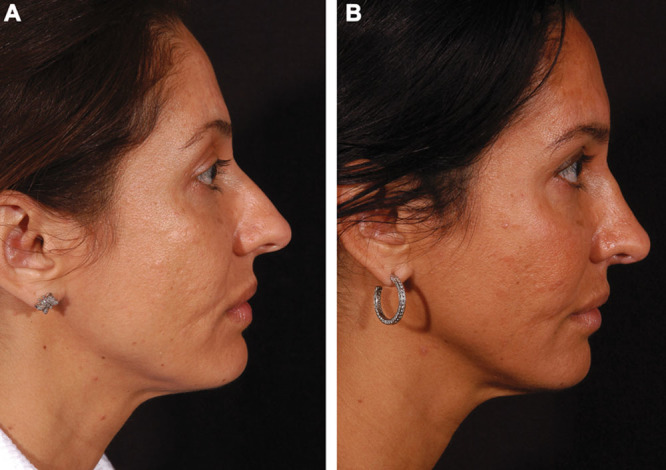

Fig. 2.

Fat grafting and rhinoplasty. Preoperative lateral (A), postoperative lateral (B), preoperative frontal (C), and postoperative frontal (D) images of a 27-year-old white woman who underwent autologous fat grafting to the nasofrontal and pyriform regions in combination with open rhinoplasty. The preoperative photographs demonstrate a “premature” forehead, atrophy of the glabella and radix, and an acute nasolabial angle. The postoperative photographs, obtained 6.5 years after the procedures, show improved contour of the lower forehead after transplantation of 19 cm3 of fat to the nasofrontal region and 16.5 cm3 to the pyriform region. Note reduction of the nasofrontal angle (from 133.4° preoperatively to 124.6° postoperatively) and greater tip rotation, with significant change in the nasolabial angle (from 51.3° preoperatively to 85.8° postoperatively).

Fig. 5.

Fat grafting alone. Preoperative lateral (A), postoperative lateral (B), preoperative frontal (C), and postoperative frontal (D) images of a 51-year-old white woman who underwent autologous fat grafting of the face. The preoperative photographs demonstrate loss of forehead volume and contour, with an obtuse nasofrontal angle and an appropriately rotated nasal tip. The postoperative photographs, obtained 5.8 years after the procedure, show greater fullness and contour of the forehead. The patient received 19 cm3 of fat in the nasofrontal region. Note improvement in the nasofrontal angle (from 137.4° preoperatively to 130.3° postoperatively) and the slight change in the nasal tip (from 94.5° preoperatively to 96.3° postoperatively) presumably due to malar, nasolabial, and upper white lip autologous fat augmentation.

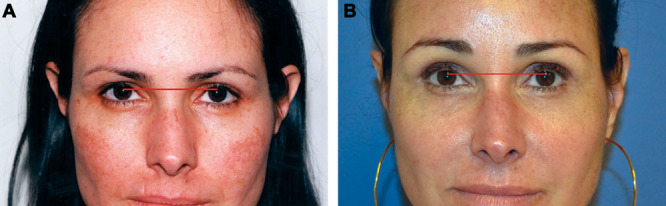

Fig. 3.

Fat grafting and rhinoplasty. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) lateral views of a 37-year-old white woman who underwent autologous fat grafting and rhinoplasty. This patient did not require any change in tip rotation. Preoperatively, the patient had a retrusive upper facial third (forehead/glabella/radix complex) and an open nasofrontal angle, contributing to the appearance of an over-projected nose. The postoperative photograph, obtained 6.3 years after the procedure, shows improvement in facial balance and contour. The patient received 12 cm3 of fat in the nasofrontal region and 18 cm3 in the pyriform region (including a posttraumatic nasolabial scar). Note reduction of the nasofrontal angle (from 141.5° preoperatively to 137.6° postoperatively), with no change in tip rotation.

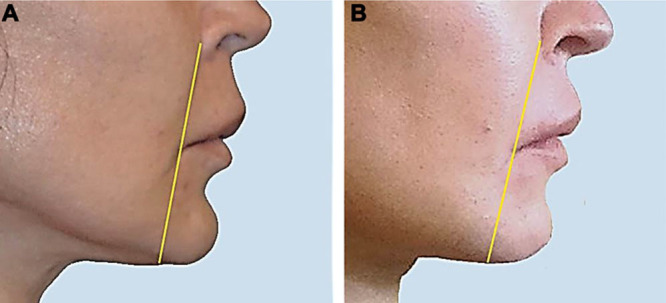

Fig. 4.

Fat grafting alone. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) lateral views of a 33-year-old white woman who underwent autologous fat grafting of the face. The preoperative photograph demonstrates flattening of the lower forehead with an open nasofrontal angle and an appropriately rotated nasal tip. The postoperative photograph, obtained 1.6 years following the procedure, shows improvement in forehead contour. The patient received 3 cm3 of fat in the nasofrontal region only. Note reduction in the nasofrontal angle (from 134.3° preoperatively to 130.5° postoperatively) and no change in tip rotation.

DISCUSSION

Rhinoplasty modifies the central feature of the face, and outcomes are judged from both frontal and lateral views. Thus, the rhinoplastic operation is inherently influenced by adjacent facial structures. A truly comprehensive approach requires consideration and, when necessary, alteration of the structures required to optimize “global” nasal aesthetics. Findings of the present study suggest that the nose can be reliably influenced by altering the contour and dimension of the forehead, glabella, and radix complex, and therefore the nasofrontal angle, as well as by stabilizing the nasal “foundation”—the pyriform aperture (known to enlarge with age)—via long-lasting autologous fat grafts.

Historically, the structures most commonly addressed in relation to the nasal profile are the radix, chin, and neck. However, Greer et al15 commented that “although rarely altered, surgeons frequently point out the lack of forehead prominence and its exacerbation of perceived nasal projection” (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Young woman with enhanced nasal prominence due to a retrusive forehead/glabella/radix complex. Image of Barbra Streisand, reprinted with permission from Steve Schapiro.

Aesthetic facial analysis begins with dividing the face into anatomic zones. Four imaginary horizontal lines are drawn: (1) at the anterior hairline, (2) at the eyebrows, (3) at the columellar-labial junction, and (4) at the edge of the chin.16 Ideally, the vertical measurements between lines 1 and 2, lines 2 and 3, and lines 3 and 4 should be equal to one another; this is commonly termed “the rule of thirds.” Therefore, the forehead represents the majority of the upper third of the face. Yet in terms of aesthetic enhancement and/or antiaging therapies, it receives surprisingly little attention. The forehead is composed of 4 lamellar components: (1) bone, (2) muscle, (3) fat pads, and (4) skin. Modifications to date have focused predominantly on the muscle and skin layers (eg, neurotoxin injections, resurfacing, and foreheadplasty). Greater attention to the bone and fat pads is critical if we are to harmonize and optimize facial anatomy and aesthetics as well as account for the changes that accompany aging. Although bone is difficult to replace and sculpt, autologous fat grafting (and/or temporary dermal fillers) may treat congenital deformities and sequelae of aging, restoring more normal anatomy, as evidenced by their direct influence on the position and contour of the brow, glabella, radix, and other structures.

Fat grafting provides a safe and long-lasting means of controlling the position of the radix. According to Sheen and Sheen,17 the “radix” denotes the origin or root of the nose. However, the nasion is the most depressed part of the nose, lying 4 mm to 6 mm deep to the glabella, at the level of the upper lid margin. Fat grafting is also a uniquely customizable means of altering the forehead and the glabella. The nasofrontal angle represents the transition between the forehead and the nose, where a soft concave curve connects the brow and the dorsum of the nose. This angle can vary from 128° to 140°, with ideal values being 134° in women and 130° in men.17

Furthermore, fat grafting to the radix may minimize complications associated with other means of radix augmentation, such as visibility, resorption, and donor-site issues, while providing a readily available solution to the thick nasal base. According to McKinney and Sweis,18 modifying (increasing) nasal radix height lessens the amount of hump or tip modification required. This is especially important in patients whose skin is thick.19 A cranial radix position creates a longer nasal dorsum with reduced anterior projection, whereas a caudal position delineates a shorter nasal dorsum and increased anterior projection.20

A deep radix reduces the nasofrontal angle, whereas a high radix opens or enlarges the nasofrontal angle. Changes associated with aging, including those affecting bone, muscle, fat, and skin, are active determinants of the nasofrontal angle. The glabella and nasion are known to retrude with advancing age.11 Bossing of the forehead may be present due to hyperaeration of the frontal sinus. Depression or flatness in the lower forehead may result from soft-tissue atrophy or bony remodeling that accompany the aging process.21 Pessa and Chen22 and other investigators21 have noted that the orbital aperture widening that occurs with aging may significantly affect the overlying soft-tissue envelope and the appearance of the aged forehead.

Changes in forehead and glabellar musculature are also dynamic, with either hypertrophy or atrophy (often due to regular neurotoxin use), enhancing or diminishing the overlying soft-tissue volume, respectively.23 Taken together, these factors directly impact the nasofrontal angle and thereby directly influence apparent nasal length and anterior projection. However, attempts to reduce a high radix by resecting bone and/or soft tissue are not as successful. According to Sheen and Sheen17 and Daniel et al,24 the response rate is 25%: 1 mm of deepening for every 4 mm of resection. This is presumably due to poor redraping of the glabellar skin, which makes deepening the radix difficult at best.

Fat grafting is also effective for influencing nasal aesthetics in frontal views. Restoring facial volume, especially in the malar region and the lateral facial fat pad, immediately and dramatically reduces the apparent size of the nose and improves harmony among facial features (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Pan facial fat grafting. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) frontal views of a 49-year-old white woman who underwent autologous fat grafting to bilateral malar regions in 2002 (right, 7 cm3; left, 4 cm3) and in 2011 (pan facial, 57 cm3). The postoperative image, obtained more than 3 years after the pan facial procedure, demonstrates apparent reduction in nasal size (width) due to restoration of facial volume. Also note the reduction in dyschromia (present preoperatively), presumably due to adipose growth factors. (No other treatments have been rendered to her face since the fat grafting.)

With respect to chin augmentation, the most common procedures are prosthetic implants and osseous genioplasty. Both typically address only a small segment of the chin, usually the caudal portion. If one considers the many anatomic changes that occur with aging, fat grafting is an ideal choice because of its versatility. Aging shortens the lower third of the face secondary to atrophy of fat, weakening of the orbicularis oris, and maxillary alveolar hypoplasia.25 Fat grafting alone, or in combination with autogenous and alloplastic augmentation, allows for greater control of chin vertical height and a more harmonious transition to adjacent structures such as the jowl, buccal, and lower lip regions, as well as ameliorating asymmetry with their contralateral counterparts (Fig. 8). Finally, restoring support for the mentalis muscle can positively affect strain and lower lip position (Fig. 9). An elevated lower lip can reflexly shorten an elongated upper lip.

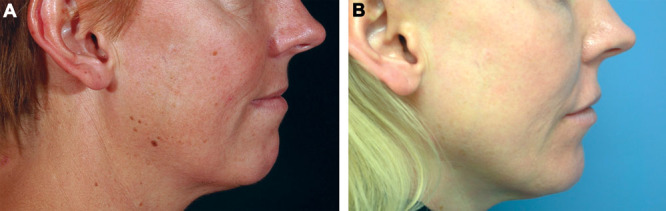

Fig. 8.

Chin augmentation with fat grafting. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) lateral views of a 58-year-old white woman who had a retrusive and vertical deficient chin as well as a deep labiomental crease and disharmony of the upper and lower lips. She received autologous fat grafting to the lower lip, labiomental groove, parasymphyseal region, and mentalis (left, 8 cm3; right, 14 cm3). Note the overall improvement in contour, which would not have been achievable by genioplasty or prosthetic augmentation alone.

Fig. 9.

Chin augmentation with fat grafting. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) lateral views of a 46-year-old white woman with a retrusive chin who underwent autologous fat grafting (13 cm3 bilaterally to the labiomental grooves, 4 cm3 to the submental crease, and 6 cm3 to the mentalis). The postoperative image was obtained 4.1 years after augmentation. Note the reduction in mentalis strain.

Aging is typically accompanied by midface retrusion.25 This includes the pyriform aperture, which remodels posteriorly relative to the upper face, resulting in loss of bony support for the alar base.12 The anterior-posterior position of the alar base is important in determining the nasolabial angle, which changes as we age. Augmenting the facial skeleton by placing hydroxylapatite beneath the alar base results in anterior reprojection and tip rotation. In the present study, fat grafting was shown to successfully rotate the tip in a manner similar to that of hydroxylapatite and may provide a more durable result. Furthermore, our results indicate that fat grafting and rhinoplasty are additive in their effects on rotating the nasal tip. Fat grafting alone rotated the tip 2.3°, whereas fat grafting plus rhinoplasty achieved rotation of 6°.

Although a patient’s soft-tissue response to the amount of injected fat is not linear, our results showed that all patients experienced improvement in forehead projection and narrowing of the nasofrontal angle.

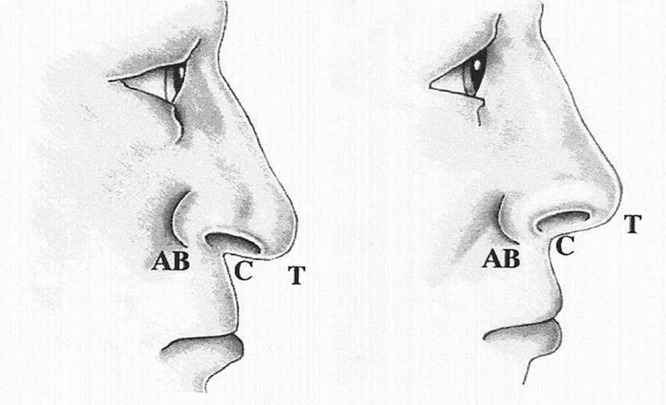

The pyriform aperture also remodels superiorly, pulling the alar base with it. This action leads to a plunging or caudal inclination of the nasal tip12 (Fig. 10). Finally, loss of skeletal support for the alar base can affect the medial foot plates, and splaying of the medial crura reduces columellar height and tip widening.12 Stabilization of the nasal base by limiting loss of skeletal support with long-term fat grafting may reduce age-related nasal changes.

Fig. 10.

Illustration of the plunging tip deformity secondary to skeletal aging. Note derotation of the nasal tip with an acute nasolabial angle due, in part, to posterior and superior atrophy of the pyriform aperture. Correction of the plunging tip includes tip rotation through alteration of the nasal base/pyriform aperture and the tip complex. Reprinted with permission from Pessa JE, Peterson ML, Thompson JW, et al. Pyriform augmentation as an ancillary procedure in facial rejuvenationsurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:683–686.12

Augmentation of the pyriform aperture restores nasal support, permits tip rotation, and may limit nasal aging by stabilizing bone resorption via adipose cell–derived vascular growth factor revascularization in and around the nasal foundation. Therefore, it is likely that some nasal revisions could be avoided by reconstitution of the nasal foundation. Long-term follow-up of patients who undergo fat grafting plus rhinoplasty may demonstrate a reduction in the number of revisions needed, owing to minimization of these skeletally induced changes.11

CONCLUSIONS

Autologous fat grafting to the forehead/glabellar/radix complex and pyriform aperture may be used consistently and reliably to modify the nasofrontal angle and the nasolabial angle, respectively. Although the interplay between the nose and the chin has been a major focus of aesthetic evaluation of the nose since the inception of rhinoplasty, its facial counterpart—the forehead—has been underappreciated, perhaps because a safe and reliable means to alter the forehead had been lacking. Autologous fat grafting brings the aesthetic evaluation of the nasal profile full circle and optimizes aesthetic balance from the frontal view. Controlling facial aging in and around the pyriform aperture potentially may reduce the number of late nasal revisions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Lynda Seminara of ClearView Medical Communications, LLC, for editorial assistance.

PATIENT CONSENT

Patients provided written consent for the use of their images.

Footnotes

This research was awarded First Prize, R.K. Daniel Resident Award, at the 19th Annual Meeting of The Rhinoplasty Society, April 24, 2014, San Francisco, Calif.

Disclosure: Dr. Kornstein is in private practice in New York City, N.Y., where he is the Director of the Museum Mile Surgery Center. He is also a member of Split Rock Surgical Associates in Wilton, Conn. Dr. Nikfarjam is a fellow in plastic and reconstructive surgery at the Montefiore Medical Center / Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, N.Y. The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joseph J. Operative Reduction of the Size of the Nose (Rhinomiosis) 1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aufricht G. Combined plastic surgery of the nose and chin; résumé of twenty-seven years’ experience. Am J Surg. 1958;95:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(58)90508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ousterhout DK. Aesthetic Contouring of the Craniofacial Skeleton. 1st ed. San Francisco, Calif.: Little, Brown and Co; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park DK, Song I, Lee JH, et al. Forehead augmentation with a methyl methacrylate onlay implant using an injection-molding technique. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:597–602. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grand Plastic Surgery. Forehead augmentation through fat grafting GRAND Plastic Surgery. Available at: http://eng.grandsurgery.com/forehead-augmentation-through-fat-grafting/. Accessed June 12, 2014.

- 6.ID Hospital. Forehead augmentation. Available at: http://eng.idhospital.com/face/face0601.php. Accessed June 12, 2014.

- 7.Guyuron B, Lee M. A reappraisal of surgical techniques and efficacy in forehead rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:426–435. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monreal J. Fat grafting to the nose: personal experience with 36 patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:916–922. doi: 10.1007/s00266-011-9681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baptista C, Nguyen PS, Desouches C, et al. Correction of sequelae of rhinoplasty by lipofilling. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moody M, Ross AT. Rhinoplasty in the aging patient. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22:112–119. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pessa JE, Desvigne LD, Zadoo VP. The effect of skeletal remodeling on the nasal profile: considerations for rhinoplasty in the older patient. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999;23:239–242. doi: 10.1007/s002669900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pessa JE, Peterson ML, Thompson JW, et al. Pyriform augmentation as an ancillary procedure in facial rejuvenation surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:683–686. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199902000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kornstein A, Nikfarjam JS. Facial rejuvenation with fat cells. In: Herman CK, Strauch B, editors. Encyclopedia of Aesthetic Rejuvenation through Volume Enhancement. 1st ed. New York, N.Y.: Thieme; 2014. pp. 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McArdle A, Senarath-Yapa K, Walmsley GG, et al. The role of stem cells in aesthetic surgery: fact or fiction? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:193–200. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greer SE, Matarasso A, Wallach SG, et al. Importance of the nasal-to-cervical relationship to the profile in rhinoplasty surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:522–531. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200108000-00037. discussion 532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyuron B. Patient assessment. In: Guyuron B, Eriksson E, Persing JA, editors. Plastic Surgery: Indications and Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 1341–1351. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheen J, Sheen A. Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. St Louis, Mo.: Mosby; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinney P, Sweis I. A clinical definition of an ideal nasal radix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1416–1418. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200204010-00033. discussion 1419–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constantian MB. An alternate strategy for reducing the large nasal base. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:41–52. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fontana AM, Muti E. Surgery of the naso-frontal angle. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20:319–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00228463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw RB, Jr, Katzel EB, Koltz PF, et al. Aging of the facial skeleton: aesthetic implications and rejuvenation strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:374–383. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f95b2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pessa JE, Chen Y. Curve analysis of the aging orbital aperture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:751–755. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200202000-00051. discussion 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohrich RJ, Hollier LH, Jr, Janis JE, et al. Rhinoplasty with advancing age. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1936–1944. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000143308.48146.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniel RK, Kosins A, Sajjadian A, et al. Rhinoplasty and brow modification: a powerful combination. Aesthetic Surg J. 2013;10:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1090820X13503474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haffner CL, Pessa JE, Zadoo VP. Craniofacial changes of the aging face analyzed with three dimensional CT scan cephalometrics. Angle Orthod. 1999;69:345–348. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1999)069<0345:ATFTDC>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]