Abstract

Objective

Marital disruption and low marital quality confer risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) in some but not all studies. Inconsistencies might reflect limitations of self-reports of marital quality compared to behavioral observations. Also, aspects of marital quality related to CAD might differ for men and women. This study examined behavioral observations of affiliation (i.e., warmth vs. hostility) and control (i.e., dominance vs. submissiveness) and prior divorce as predictors of coronary artery calcification (CAC) in older couples.

Methods

Couples underwent CT scans for CAC and marital assessments including observations of laboratory-based disagreement. Participants were 154 couples (mean age = 63.5; mean length of marriage = 36.4 years) free of prio diagnosis of CAD.

Results

Controlling traditional risk factors, behavioral measures of affiliation (low warmth) accounted for 6.2% of variance in CAC for women, p<.01, but not for men. Controlling behavior (dominance) accounted for 6.0% of variance in CAC for men, p<.02, but not for women. Behavioral measures were related to self-reports of marital quality, but the latter were unrelated to CAC. History of divorce predicted CAC for men and women.

Conclusions

History of divorce and behavioral – but not self-report – measures of marital quality were related to CAD, such that low warmth and high dominance conferred risk for women and men, respectively. Prior research might underestimate the role of marital quality in CAD by relying on global self-reports of this risk factor.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, coronary calcification, marital quality, interpersonal circumplex, structural analysis of social behavior, dominance, affiliation

INTRODUCTION

Supportive social relationships are associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) (1). As the central personal relationship for many adults, marriage similarly confers reduced CHD risk (2,3). However, marital quality is important. Marital disruption (i.e., separation, divorce) and strain (i.e., conflict, dissatisfaction) predict hypertension and related complications (4), atherosclerosis (5), incident CHD (6,7), and poor prognosis among heart patients (8,9). As potential underlying mechanisms, negative marital interactions evoke cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and cardiovascular stress responses (10,11), whereas supportive interactions attenuate them (12). However, some studies find no association between marital quality and asymptomatic atherosclerosis (13), and others find associations with atherosclerosis in some sites (e.g., carotid arteries) but not the coronary arteries (5). Hence, the role of marital quality in pre-clinical coronary artery disease (CAD) is unclear.

Methodological and conceptual issues may contribute to these mixed findings. Assessment of marital status and disruption is straightforward, but measurement of other aspects of marital quality is more complex. Previous studies of atherosclerosis have relied on self-reports of marital satisfaction or conflict, which generally have well-documented validity (14). However, behavioral ratings obtained through direct observation of marital interactions can capture aspects of marital quality that self-reports do not (14,15). Hence, effects of marital quality on CAD may be more apparent with behavioral assessments.

Further, prior studies generally conceptualize marital quality as a single dimension. Interpersonal theories (16) label this dimension of social relations as affiliation, varying from friendliness and warmth to hostility and quarrelsomeness. The second major dimension described by those theories – control or dominance versus submissiveness – is an important component of marital quality, as perceptions of being excessively or unfairly controlled by a spouse undermine marital satisfaction and increase conflict (17,18,19). Further, individual differences in controlling interpersonal behavior (i.e., social dominance) are implicated in CHD development (20).

Consideration of both affiliation and control could clarify sex differences in which women are more susceptible to the negative health effects of low marital quality (21). Women are often more distressed by low affiliation in relationships than are men, whereas men are often more concerned with issues involving control (22,23). Hence, variations in affiliation in marriage may be more relevant to women's CHD risk, whereas control may be more relevant for men. Measurement of affiliation but not control in studies of marital quality and cardiovascular health may have limited previous research.

The affiliation and control dimensions also contain more specific information. Within affiliation, warmth and hostility are independently related to marital quality (24), and might be differentially related to CAD. Within control, dominant behavior could heighten risk, whereas submissiveness could reduce it. Alternatively, dominance or submissiveness could be related to CHD risk differently for men and women (25).

The present study examined associations of behavioral ratings of affiliation and control obtained during a laboratory-based marital disagreement and history of divorce with severity of CAD – measured as coronary artery calcification (CAC) - in healthy older couples. We tested the specific hypotheses that prior divorce would be associated with greater CAC, and that (low) affiliation would be associated with CAC severity for women but control would not. In contrast, we predicted that control would be related to men's CAC but affiliation would not. To capture behavioral indications of these aspects of marital quality, we examined both partners’ levels of affiliation and control as predictors of CAC, as well as the interaction of these predictors. Specifically, women in couples where both partners are high in hostility or low in warmth could be at particularly high risk, as could men in couples where both partners display high levels of dominance. A high level of reciprocating hostility is a hallmark of marital strain (14,15), and high dominance displayed by both partners could reflect pointed struggles for control. We also examined components of affiliation (i.e., warmth, hostility) and control (i.e., dominance, submissiveness) to explicate significant effects of the overall dimensions.

Personality traits involving negative emotionality and maladaptive social behavior confer risk for divorce (26,27). Hence, hostile or controlling marital interactions might be more common among previously divorced persons, and this prior marital stress exposure or the related personality traits could underlie associations between current marital behavior and CAD (6). Hence, we also controlled personality and prior history of divorce when testing associations of marital behavior with CAC. Finally, participants’ self-reports of anger during the marital interaction and general marital adjustment were used to confirm the validity of behavioral assessments and compare self-reports and behavioral observations of marital quality as predictors of CAC.

METHODS

Participants

The Utah Health and Aging Study (28,29), approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board, enrolled 154 older couples during 2001 – 2005. Couples from the Salt Lake City metropolitan area were recruited through a polling firm, newspaper advertisements, and community programs. Participants met the following criteria: 1) at least one member between 60 and 70 years old, 2) no more than 10 year age difference, 3) no history of cardiovascular disease, and 4) not taking cardiovascular medications (e.g., beta-blockers). Women averaged 62.2 years of age (range = 50 – 71) and men 64.7 (52 – 76). Consistent with local demographics, 95.4% were non-Hispanic white, and the median household income was $50,000 – 75,000 per year. Mean length of marriage was 36.4 years (5 – 53 years), and 76% were in their first marriage (17% second). In this paper we report analyses of older but not middle-aged couples, given the low prevalence of CAC in the latter group (28).

Procedures

Participants independently completed informed consent forms and marital quality questionnaires before their laboratory session, which included a disagreement discussion, videotaped for behavioral coding. Spouses rated their disagreement on 13 topics (e.g., money, household duties) (30). Topics with the greatest combined rating were used for discussion. Couples were informed that, “we are not expecting you to solve the particular issue right now; you can think of this as an opportunity to work toward making progress on the issue.” Participants engaged in an initial 6-minute conversation about the topic, used for coding (14,15). Participants underwent medical clinic visits for evaluation of biomedical risk factors and CAC measurement approximately one week later.

Behavioral Ratings and Psychosocial Measures

Measures of marital quality, state affect, and personality

Participants completed the Marital Adjustment Test (MAT), a measure of marital satisfaction with well-established reliability and validity (31), and the conflict subscale of the Quality of Relationship Inventory (32). On a 6-item state anger measure with adequate reliability and validity (33), participants indicated how they felt after a baseline period and again after the disagreement task. Previously in this sample, we reported that spouse ratings of participants’ personality trait levels of dominance and (low) affiliation were related to CAC (20), using scales with adequate reliability and construct validity (19,20).

Behavioral coding

Videotaped interactions were coded using the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) (34) - specifically, the SASB-Composite Observational Coding Scheme (SASB-COMP) (35). Details of coding can be found elsewhere (29). Twenty percent of tapes were randomly selected for reliability coding, with an average inter-rater reliability assessed by intraclass correlation (36) of .88.

SASB codes were combined to represent the interpersonal circumplex (IPC: Figure 1). Specifically, warmth or friendliness codes were combined to form an index (corresponding to LM, NO, and JK IPC octants in Figure 1). Codes reflecting hostility were similarly combined (DE, BC, and FG octants). Codes reflecting dominance were combined (PA, BC, and NO octants), as were codes reflecting submission (HI, FG, and JK octants). Scores for individual codes were converted to standardized proportions before combining to form warmth, hostility, dominance and submission scores. Total affiliation scores were calculated as warmth – hostility, and total control as dominance – submission. Inter-rater reliability (Pearson r) for affiliation and control composites and their components were all greater than r = .85. Evidence of the validity of behavioral assessments in this sample can be found elsewhere (29), and in correlations among husbands’ and wives’ psychosocial variables presented in Table 1. For example, behavioral ratings of warmth were positively associated with reports of marital adjustment and inversely associated with reports of marital conflict and anger during the disagreement. Behavioral ratings of hostility and dominance were associated with lower marital adjustment and reports of greater conflict and anger.

Figure 1.

The Interpersonal Circumplex

Table 1.

Correlations among Behavioral Ratings and Self-Reports of Marital Quality, for Wives and Husbands Considered Separately

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affiliation | .61 | -.59 | -.34 | -.19 | .37 | .23 | -.29 | -.19 | |

| 2. Warmth | .64 | -.27 | -.48 | -.45 | .33 | .18 | -.19 | -.25 | |

| 3. Hostility | -.61 | -.31 | .62 | .55 | -.46 | -.15 | .24 | .24 | |

| 4. Control | -.14 | -.23 | .22 | .81 | -.81 | -.22 | .24 | .29 | |

| 5. Dominance | -.54 | -.59 | .61 | .70 | -.31 | -.29 | .32 | .31 | |

| 6. Submissiveness | -.39 | -.33 | .37 | -.62 | .12 | .07 | -.07 | -.15 | |

| 7. Adjustment | .35 | .28 | -.34 | -.13 | -.39 | -.24 | -.64 | -.14 | |

| 8. Conflict | -.36 | -.26 | .35 | .14 | .40 | .25 | -.71 | .34 | |

| 9. State Anger | -.21 | -.21 | .22 | .20 | .35 | .10 | -.24 | .20 |

Correlations among wives’ measures left of diagonal, husbands’ values right of diagonal. N = 154 r values > .17 are significant, p<.05, two-tailed

Coronary Artery Calcification and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Participants underwent coronary artery scans on a multidetector scanner (Phillips MX8000, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH), using 2.5-mm collimation transverse slices obtained from 2-cm inferior to the carina to the inferior margin of the heart. On each gantry rotation four 2.5-mm slices were obtained. Scans were obtained in a single breath-hold using 500 msec exposure and axial (non-spiral) mode imaging. Using ECG-triggering, image acquisition was initiated during diastole corresponding to 50% of the R-R interval. Image reconstruction was performed using a 220-mm field of view and a 512 × 512 matrix with a standard reconstruction filter, giving a nominal pixel area of 0.18-mm2 and voxel volume of 0.46-mm3. To equate CAC scores to electron-beam scanners using the method of Agatston (37), multidetector imaging scores were multiplied by 0.833 (2.5mm/3.0mm) to compensate for thinner collimation. For women and men, 51.3% and 81% respectively had detectable CAC. CAC is closely related to other measures of CAD and prospectively associated with CHD events (38). Fasting blood draws were used to obtain glucose levels and plasma lipids. Sitting blood pressures were the average of three consecutive readings. Behavioral risk factors (i.e., smoking status) were assessed via self-report. (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Levels of Traditional Risk Factors

| Wives | Husbands | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | 27.4 (4.8) | 27.8 (4.0) |

| Total Cholesterol | 202.7 (34.5) | 182.0 (33.2) |

| Triglycerides | 137.8 (82.5) | 128.0 (64.1) |

| HDL | 60.7 (16.5) | 47.3 (12.9) |

| LDL | 118.6 (28.3) | 111.3 (28.8) |

| MAP mmHg | 88.0 (13.6) | 93.7 (10.7) |

| Glucose | 90.6 (20.1) | 93.3 (18.0) |

| Smoking Status % | ||

| Never | 79.2 | 62.7 |

| Former | 19.5 | 35.3 |

| Current | 1.3 | 2.0 |

| Alcohol Use % | ||

| Rare or Never | 61.1 | 56.0 |

| Low | 20.8 | 16.0 |

| Moderate to High | 18.1 | 28.0 |

| Exercise Level % | ||

| Sedentary | 10.1 | 5.3 |

| Mild | 26.8 | 29.3 |

| Moderate | 36.2 | 29.3 |

| High | 26.8 | 36.0 |

| Marital Adjustment Test | 117.4 (25.6) | 121.2 (21.4) |

| MAT range | (14 – 154) | (45 – 156) |

Data reported as means (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

Statistical Analyses

Consistent with recommendations, we transformed Agatston scores as nlog (1 + CAC) (39). All structural equation modeling (SEM) and regression analyses reported below controlled age, biomedical risk factors (i.e., BMI, MAP, fasting glucose, diabetes, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL), and behavioral risk factors (i.e., smoking, exercise, alcohol use, household income). In analyses of behavioral measures of marital quality three predictors were included, representing either affiliation or control: a) the wife's level of affiliation (or control), b) the husband's affiliation (or control), and c) the two-way interaction. Predictors were centered prior to calculation of interactions.

To accommodate dependent observations, SEM analyses tested associations between marital variables and husbands’ and wives’ CAC simultaneously with the inclusion of an error covariance between husbands’ and wives’ outcomes (40). Using Mplus version 5.21 (41), we tested model comparisons corresponding to specific hypotheses (40,42). In each case we relied on the chi-square difference test for nested models, which has an interpretation similar to the R-square change test in hierarchical regression. For example, in analyses of behavioral assessments, we first compared a model where associations between the three marital predictors (e.g., wife's affiliation, husband's affiliation, wife × husband interaction) and both wives’ and husbands’ CAC were permitted to vary freely (i.e., full model) to a model where these associations were not estimated (i.e., base model). As described above, we expected that affiliation would be associated with wives’ but not husbands’ CAC, and that control would be associated with husbands’ but not wives’ CAC. To test the sex differences more directly, the base model was compared to models in which effects of one sex were fixed at zero and those for the other sex were permitted to vary freely. These comparisons tested the specific hypotheses that expected associations for a given sex (e.g., affiliation associated with wives’ CAC; control with husbands’ CAC) would result in improved fit over the base model. Finally, to determine if effects for one sex were significantly different from effects for the other (e.g., associations of affiliation with wives’ CAC significantly greater than with husbands’ CAC), we compared models in which effects were permitted to vary freely (i.e., full model) to one in which the effects were fixed as equal for husbands and wives. In these analyses, covariates (i.e., age, other risk factors as described above) were allowed to freely covary with the other exogenous variables and each other, but only predicted participants’ own outcomes (e.g. wife's age predicted her own CAC).

SEM analyses of dyad data currently lack a well-established and widely-accepted index of effect size. Therefore, we followed significant results of SEM analyses with multiple regressions considering wives or husbands separately, in which a block of marital predictors (i.e., wives’ behavior, husbands’ behavior, two-way interaction) was added after effects of age and other risk factors. Parallel regression analyses examined two components of control (i.e., dominance, submissiveness) and affiliation (i.e., warmth, hostility) to explicate significant effects for the overall dimensions. Significant interactions were explicated through simple slope analyses at one SD above and below the mean (43,44). Graphs of interactions based on SEM and regression results were virtually identical. Given the a-priori predictions, significance levels for effects of affiliation and control are not adjusted for multiple tests.

RESULTS

Marital Disruption and CAC

Freely estimating associations between husbands’ and wives’ own history of divorce and their own CAC resulted in a significant improvement in model fit over a base model where both paths were fixed to zero, Χ2(2) = 11.96, p = .003. The effect of divorce history was significant for both wives (estimate = .69; SE = .33, p = .037) and husbands (estimate = 1.33, SE = .46, p = .003). (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean coronary artery calcification for men and women as a function of prior history of divorce, controlling age and traditional risk factors (+/- SE)

Association of Affiliation during Disagreement with CAC

In SEM analyses for affiliation, the full model in which all six associations between affiliation variables (i.e., wives’ affiliation, husbands’ affiliation, two-way interaction) and CAC (i.e., wives, husbands) were estimated freely was a significant improvement in fit over the base model without these paths, Χ2(6) = 12.66, p = .049. As depicted in Figure 3, effects for wives’ affiliation, p = .008, and the two-way interaction, p = .028, were significant. Also as expected, none of the effects approached significance for husbands (all p values > .2). In more specific tests of expected sex differences, a model in which effects of affiliation on wives’ CAC were estimated freely and those on husbands’ CAC were fixed at zero resulted in an improved fit over the base model, Χ2(3) = 10.93, p = .012. Also as expected, a model in which effects of affiliation on husbands’ CAC were estimated freely and those on wives’ CAC were set at zero did not, Χ2(3) = 1.23, p = .75. However, in a direct test of the difference between effects of affiliation on wives’ versus husbands’ CAC, a model in which all six effects were estimated freely did not result in a better fit when compared to a model which held effects for husbands and wives equal, Χ2(3) = 2.82, p = .42. Hence, wives’ own affiliation and the interaction between wives’ and husbands’ affiliation were significantly related to wives’ CAC, whereas as none of the affiliation variables were related to husbands’ CAC. Associations involving wives’ CAC resulted in an expected significant improvement in model fit, and as expected the parallel associations involving husbands’ CAC did not. However, evidence of this sex difference was not found in the most stringent test; associations involving wives’ CAC were not significantly larger than those involving husbands’ CAC.

Figure 3.

Dyadic analysis results for behavioral assessments of affiliation predicting coronary calcification (full model as described in text). Significant paths are depicted as solid lines; estimated but non-significant paths as dotted lines. Analyses control age and biologic and psychosocial risk factors as described in text.

In follow-up regression analyses of women's CAC, the effect of age was significant, ΔR2 = .148, F(1, 141) = 25.56, p <.001, as was the set of other risk factors (BMI, cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL,LDL, MAP, glucose, diabetes, smoking, alcohol, exercise, income), ΔR2 = .16, F(12,129) = 2.49, p = .006. Consistent with the SEM results, the block of three effects for behavioral assessments of affiliation accounted for additional significant variance in wives’ CAC, ΔR2 = .062, F(3,126) = 4.12, p = .008. The first order effect for wives’ affiliation was significant, unstandardized coefficient = -.019 (SE = .008), t(126) = 2.31, p = .03, semi-partial r2 = .026, as was the interaction of wives’ and husbands’ affiliation, unstandardized coefficient = .002 (SE = .001), t(126) = 2.34, p = .021. semi-partial r2 = .028 (see Figure 4 - panel A). In simple slope analyses, wives’ affiliation was most strongly (inversely) associated with wives’ CAC where husbands displayed low affiliation, stdβ = -.309, t(126) = 2.90, p = .004, less strongly where husbands displayed average affiliation, stdβ = -.182, t(126) = 2.22, p=.028, but not where husbands displayed high affiliation. Further, husbands’ affiliation was inversely related to wives’ CAC among wives who displayed low affiliation, stdβ = -.230, t(126) = 2.18, p = .031, but not among wives who displayed average or high affiliation. The block of affiliation effects remained significant when controlling husbands’ ratings of wives’ personality, F(3, 125) = 3.27, p = .024, ΔR2 = .050, and divorce history, F(3,125) = 3.34, p = .021, ΔR2 = .050. When controlling the block of affiliation effects, wives’ history of divorce was marginally related to their CAC, stdβ = .138, t(125) = 1.87, p = .064.

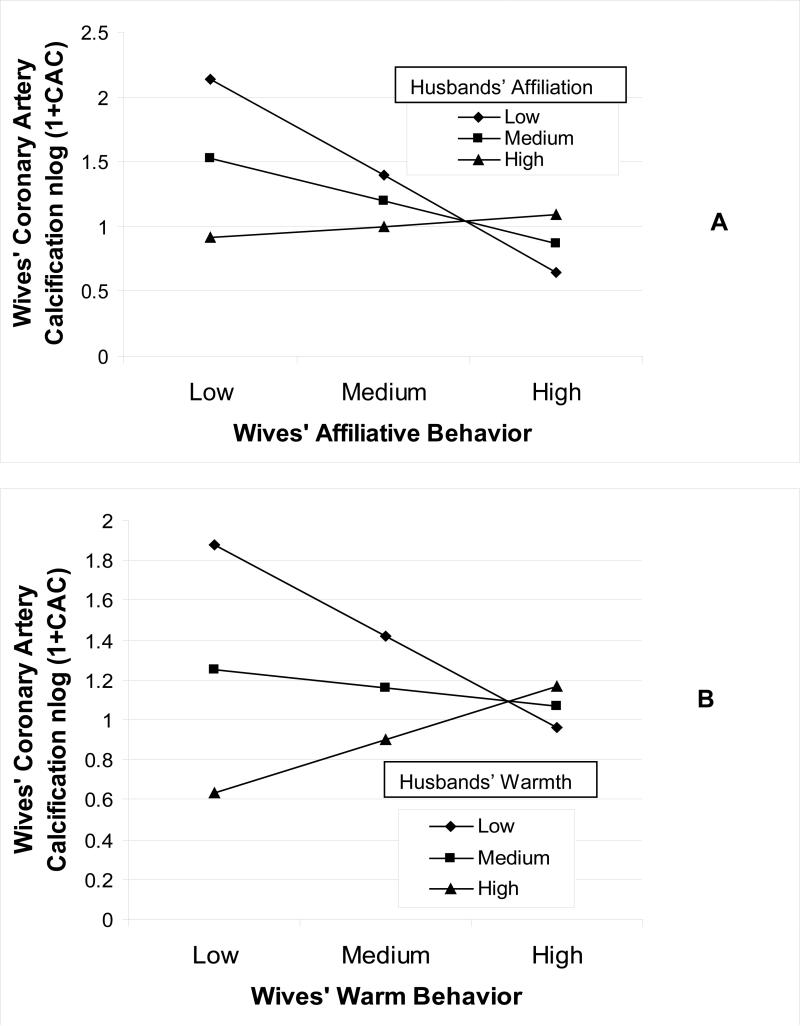

Figure 4.

Predicted values (+1 SD, mean, -1 SD) for associations of behavioral assessments of couple affiliation (Panel A) and warmth (Panel B) during disagreement with wives’ coronary artery calcification.

Considering the two components of affiliation, the block of hostile behavior effects was unrelated to wives’ CAC, ΔR2 = .020, F(3,126) = 1.21, p = .31. However, the block for warmth accounted for significant variance beyond age and traditional risk factors, ΔR2 = .059, F(3,126) = 3.92, p = .01, and the interaction of wives’ and husbands’ warmth was significant, unstandardized coefficient = .002, (SE = .001), t(126) = 2.61, p = .01, semi-partial r2 = .034 (Figure 4 - panel B). Wives’ warmth was inversely related to their CAC only if husbands also displayed low warmth, stdβ = -.244, t(126) = 2.26, p = .026. Husbands’ warmth was inversely related to wives’ CAC only if wives also displayed low warmth, stdβ = -3.27, t(126) = 2.91, p = .004. Hence, wives in couples where both members were low in warmth had high CAC.

Association of Controlling Behavior during Disagreement with CAC

In SEM analyses for control, the full model in which all six possible associations between behavioral control variables (i.e., wives’ control, husbands’ control, two-way interaction) and CAC (i.e., wives, husbands) were estimated freely was a marginally significant improvement in fit over the base model, Χ2(6) = 11.11, p = .085. As expected and depicted in Figure 5, wives’ control, p = .035, and the two-way interaction, p = .018, were significantly related to husbands’ CAC; the association of husbands’ control with their own CAC approached significance, p = .07. Also as expected, none of the effects of control for wives’ CAC approached significance (all p values > .3). In more specific tests of expected sex differences, a model in which effects of control on husbands’ CAC were estimated freely and those for wives’ CAC were fixed at zero resulted in an improved fit over the base model, Χ2(3) = 9.82, p = .02. Also as expected, a model in which effects of control for wives’ CAC were estimated freely and those on husbands’ CAC were set at zero did not improve fit, Χ2(3) = 0.85, p = .84. However, the full model in which all six effects were estimated freely did not result in better fit when compared to a model in which effects for husbands and wives were fixed as equal, Χ2(3) = 2.82, p = .42. Hence, as expected, associations of wives’ control and the interaction between wives’ and husbands’ control with husbands’ CAC were significant, and the association of husbands’ controlling behavior with their own CAC approached significance. In contrast, none of the associations of control with wives’ CAC were significant. Also as expected, the associations involving husbands’ CAC resulted in a significant improvement in model fit, and the parallel associations involving wives’ CAC did not. However, support for this sex difference was not found in the most stringent test; the associations involving husbands’ CAC were not significantly larger than those involving wives’ CAC.

Figure 5.

Dyadic analysis results for behavioral assessments of control predicting coronary calcification (full model as described in text). Significant paths are depicted as bold solid lines. Marginal associations depicted as thin solid lines; estimated but non-significant paths as dotted lines. Analyses control age and biologic and psychosocial risk factors as described in text.

In follow-up regression analyses for husbands’ CAC, the effect of age was significant, ΔR2 = .028, F(1,141) = 4.05, p = .046, as was the set of other risk factors (BMI, cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL,LDL, MAP, glucose, diabetes, smoking, alcohol, exercise, income), ΔR2 = .176, F(12,129) = 2.40, p = .008. As predicted the block of behavioral control variables significantly predicted husbands’ CAC, beyond age and traditional risk factors, ΔR2 = .06, F(3,126) = 3.42, p = .019. The first order effect of wives’ control was significant, unstandardized estimate = .035 (SE = .015), t(126) = 2.41, p = .008, semi-partial r2 = .033, as was the interaction of husbands’ and wives’ control unstandardized estimate = -.002 (SE = .001), t(126) = 2.35, p = .021, semi-paritial r2 = .032 (see Figure 6, panel A). In simple slope analyses, wives’ control was positively associated with husbands’ CAC most strongly in couples where husbands displayed low control, stdβ = .330, t(126) = 3.04, p = .003, less strongly where husbands’ displayed average control, stdβ = .179, t(126) = 2.21, p= .029, but not in couples where husbands displayed high control. Further, husbands’ control was related to their CAC where wives’ displayed low control, stdβ = .213, t(126) = 1.98, p = .05, but not if wives displayed average or high levels. The block of control effects was significant when controlling wives’ ratings of their husbands’ personality, F(3, 125) = 3.24, p = .024, ΔR2 = .053, and divorce history, ΔR2 = .056, F(3,125) = 3.32, p = .022. When entered after the block of effects for control behavior, husbands’ history of divorce was significantly related to their CAC, stdβ = .225, t(125) = 2.68, p = .008.

Figure 6.

Predicted values (+1 SD, mean, -1 SD) for associations of behavioral assessments of couple control (Panel A) and dominant behavior (Panel B) during disagreement with husbands’ coronary artery calcification.

In analyses of the two components of control (i.e., dominance, submissiveness), the block for submissive behavior was unrelated to husbands’ CAC, ΔR2 = .007, F(3,126) = 0.35, p = .79. In contrast, the block for dominant behavior accounted for significant variance in husbands’ CAC beyond age and traditional risk factors, ΔR2 = .053, F(3,126) = 3.00, p = .033. The first order effect of wives’ dominance was significant, unstandardized coefficient = .040 (SE = .018), t(126) = 2.24, p = .025, semi-partial r2 = .030, and the interaction of wives’ and husbands’ dominance approached significance, unstandardized coefficient = -.003 (SE = .002), t(126) = 1.94, p = .055, semi-partial r2 = .021 (see Figure 6 - panel B). Simple slope analyses indicated that wives’ dominance was most strongly associated with husbands’ CAC in couples where husbands’ displayed low dominance, stdβ = .325, t(126) = 2.99, p = .003, less closely where husbands displayed average dominance, stdβ = .186, t(126) = 2.28, p = .029, but not where husbands displayed high dominance. Further, husbands’ dominant behavior was related to their own CAC where wives displayed low dominance, stdβ = .278, t(126) = 2.06, p = .041, but not where wives’ displayed average or high dominance. This pattern suggests that whether measured as total control or more specifically as dominance, this dimension of disagreement behavior was related to husbands’ CAC such that both their own and their wives’ dominance was associated with more severe CAC. However, high dominance in both spouses did not further exacerbate CAC. Instead, a pattern of low dominance for both members was associated with particularly low levels of husbands’ CAC.

Associations of Self-Reports of Marital Quality and Anger with CAC

Although behavioral measures, self-reports of marital quality, and reported anger during disagreement were significantly associated as expected (see Table 1), no self-report was associated with CAC for either husbands or wives, all p >.30.

DISCUSSION

These results suggest that low marital quality is associated with CAD in otherwise healthy older couples. However, this conclusion must be qualified in light of key findings. First, a history of divorce and behavioral assessments of marital quality from direct observation were associated with CAC, but self-reports of marital quality were not. Further, different dimensions of marital behavior were related to CAC for men and women. As predicted, for women variations in affiliation were related to CAC; women who displayed low levels of affiliation during disagreement had higher levels of CAC, especially if their husbands also displayed low affiliation. When warmth and hostility were examined separately, hostile behavior was unrelated to wives’ CAC, but women who displayed little warmth during disagreement had higher levels of CAC if their husbands also displayed little warmth. These results could not be attributed to age, traditional biomedical and behavioral risk factors, women's personality trait levels of affiliation, or women's prior history of divorce.

For men, affiliation was unrelated to CAC. Instead, as predicted, couple patterns of control were related to men's CAC. Men whose wives displayed high levels of control during disagreement had higher levels of CAC, and a marginally significant association suggested that men who themselves were controlling also tended to have higher levels of CAC. Husbands’ and wives’ control during disagreement interacted in their association with husbands’ CAC, but not in a manner that suggested potentiated effects of contested control. Rather, men in couples displaying little control had low levels of CAC, and control exhibited by either partner increased risk. When components of control were examined separately, dominant but not submissive behavior was related to men's CAC. These effects of control were independent of age, traditional biomedical and behavioral risk factors, and men's personality trait levels of dominance and prior history of divorce.

These results are consistent with the view that the affiliation dimension of social relations is more relevant for women's health than is control, whereas control is the more relevant dimension for men (22,23). The associations of behavioral interaction patterns with self-reports of anger during disagreement and with overall marital quality are consistent with prior research regarding behavioral correlates of marital functioning (14,15) and support the validity of the SASB-based measures. These effects also suggest that the somewhat surprising result that hostile behavior was unrelated to wives’ CAC cannot be seen as reflecting limitations of this observational measure, as it was associated with marital quality and anger during the task.

These results raise the question of mechanisms underlying associations of marital interaction patterns and prior divorce with CAD. Low marital quality and marital disagreements are associated with heightened levels of cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and inflammatory stress responses that promote CAD (10,11,33), whereas warm or supportive social contexts and interactions attenuate such responses (12). Further, marital interactions that pose threats to affiliation have been found to evoke cardiovascular reactivity more readily in women than men, whereas the opposite sex difference occurs for interactions that activate concerns about status and control in the relationship (23,45). Such cardiovascular responses have been found to predict CAC (46).

Several limitations of these findings must be noted. The cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about the causal direction of associations between marital quality and CAC. Given the exclusion of participants with cardiovascular disease, it seems unlikely that observed effects reflect couples’ behavioral reactions to CAD. However, longitudinal studies are needed. Further, the sample is largely Caucasian and middle or upper-middle class, and heterosexual married couples. Generalization to other groups requires further research. Also, the sample is small for studies of cardiovascular risk. Although time-intensive behavioral assessments of marital quality would be difficult to use in large-scale studies, replications with larger samples is important. Also, statistical control of potential confounds (e.g., traditional risk factors) sometimes results in under-correction and residual confounding (47). Finally, although the different patterns of associations of marital behavior and CAC for men and women corresponded closely to a-priori hypotheses, when these sex differences were tested directly the parallel associations for men and women were not significantly different, perhaps due to the small sample size and resulting low power to detect interactions. Hence, conclusions regarding different effects for men and women must be made cautiously.

CONCLUSIONS

These qualifications notwithstanding, the results suggest that exposure to low marital quality may be a risk factor at early stages of CHD. In the present findings, for women this risk takes the form of low levels of warmth during potentially stressful marital interactions, and a history of divorce. For men, prior divorce and high levels of controlling or dominant behavior during marital interactions may confer risk. Hence, marital disruption and low levels of quality marital are associated with increased CAD risk, but the relevant aspects of quality may differ for men and women.

The consistent associations between these behavior patterns and self-reports of marital quality demonstrate that commonly-used methods of assessing this psychosocial risk factor indeed tap unhealthy personal relationship exposures. However, the results also suggest that associations with CAD and perhaps CHD may be weaker when self-report measures of marital quality are used. These findings also illustrate the utility of interpersonal concepts and methods such as the IPC and SASB coding system in the study of psychosocial risk for CHD. This theoretical and measurement framework is broadly applicable in quantifying and integrating a wide range of personality, social, and social-environmental risk factors, and in examining underlying mechanisms (19,20,48). Across these applications, two basic dimensions of interpersonal behavior - affiliation and control - appear to be important influences on cardiovascular health.

Funding/Support

This work was supported grant number RO1 AG 18903 (Timothy W. Smith, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, awarded to T.W. Smith (PI; C.A Berg, co-PI; B.N Uchino, P. Florsheim, P.N. Hopkins, and H-C Yoon, co-investigators).

Abbreviations

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CAC

coronary artery calcification

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- IPC

interpersonal circumplex

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- SASB

structural analysis of social behavior

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Conflicts of Interest: None reported

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev of Public Health. 2005;26:469–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan RM, Kronick RG. Marital status and longevity in the United States population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:760–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruberman W, Weinblatt E, Goldberg JD, Chaudhary BS. Psychosocial influences on mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl JMed. 1984;311:552–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408303110902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker B, Paquette M, Szalai JP, Driver H, Perger T, Helmers K, O'Kelly B, Tobe S. The influence of marital adjustment on 3-year left ventricular mass and ambulatory blood pressure in mild hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3453–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallo LC, Troxel WM, Kuller LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Edmundowicz D, Matthews KA. Marital status, marital quality, and atherosclerotic burden in postmenopausal women. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:952–62. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097350.95305.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews KA, Gump BB. Chronic work stress and marital dissolution increase risk of posttrial mortality in men from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:309–15. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vogli R, Chandola T, Marmot MG. Negative aspects of close relationships and heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1951–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohrbaugh M, Shoham V, Coyne J. Effect of marital quality on eight-year survival of heart patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2006. 2006;98:1069–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orth-Gomer K, Wamala SP, Horsten M, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Schneiderman N, Mittleman MA. Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: The Stockholm female coronary risk study. JAMA. 2000;284:3008–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: pathways to health. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:409–16. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, Glaser R. Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1377–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29:377–87. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janiciki D, Kamarck T, Shiffman S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Gwaltney C. Frequency of spousal interaction and 3-year progression of carotid artery intima medial thickness: the Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:889–96. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188476.87869.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snyder DK, Heyman RE, Haynes SN. Evidence-based approaches to assessing couple distress. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:288–307. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heyman RE. Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychol Assess. 2001;13:5–35. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiesler DJ. The 1982 interpersonal circle: A taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychol Rev. 1983;90:185–214. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray-Little B, Burks N. Power and satisfaction in marriage: A review and critique. Psychol Bull. 1983;93:513–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrensaft MK, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Heyman RE, O'Leary KD, Lawrence E. Feeling controlled in marriage: A phenomenon specific to physically aggressive couples? J Fam Psychol. 1999;13:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith TW, Traupman E, Uchino BN, Berg CA. Interpersonal circumplex descriptions of psychosocial risk factors for physical illness: Application to hostility, neuroticism, and marital adjustment. J Personal. 2010;78:1011–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith TW, Uchino BN, Berg CA, Florsheim P, Pearce G, Hawkins M, Henry N, Beveridge R, Skinner M, Hopkins PN, Yoon HC. Self-reports and spouse ratings of negative affectivity, dominance and affiliation in coronary artery disease: Where should we look and who should we ask when studying personality and health? Health Psychol. 2008;27:676–84. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiecolt-Glaser J, Newton T. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helgeson VS. Relation of agency and communion to well-being: Evidence and potential explanations. Psychol Bull. 1994;116:412–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith TW, Gallo LC, Goble L, Ngu LQ, Stark KA. Agency, communion, and cardiovascular reactivity during marital interaction. Health Psychol. 1998;17:537–45. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fincham FD, Linfield K. A new look at marital quality: can spouses be positive and negative about their marriage? J Fam Psychol. 1997;9:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaker ED, Sullivan LM, Kelly-Hayes M, D'Agostino RB, Benjamin EJ. Marital status, marital strain, and risk of coronary heart disease and total mortality: The Framingham Offspring Study. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:509–13. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f62357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jockin V, McGue M, Lykken DT. Personality and divorce: a genetic analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71:288–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whisman MA, Tolejko N, Chatav Y. Social consequences of personality disorders: probability and timing of marriage and probability of marital disruption. J Personal Disord. 2007;21:690–5. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith TW, Uchino BN, Berg CA, Florsheim P, Pearce G, Hawkins M, Hopkins P, Yoon HC. Hostile personality traits and coronary artery calcification in middle-aged and older married couples: Different effects for self-reports versus spouse-ratings. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:441–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180600a65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith TW, Berg CA, Florsheim P, Uchino BN, Pearce G, Hawkins M, Henry NJM, Beveridge R, Skinner M, Olson-Cerny C. Conflict and collaboration in middle-aged and older couples: I. Age differences in agency and communion during marital interaction. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:259–73. doi: 10.1037/a0015609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fincham FD. Attribution processes in distressed and nondistressed couples: Responsibility for marital problems. J Abnorm Psychol. 1985;94:183–90. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locke H, Wallace K. Short marital adjustment and prediction tests: their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21:251–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce G, Sarason I, Sarason B. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:1028–39. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nealey-Moore JB, Smith TW, Uchino BN, Hawkins MW, Olson-Cerny C. Cardiovascular reactivity during positive and negative marital interactions. J Behav Med. 2007;30:505–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benjamin LS, Rothweiler J, Critchfield K. The use of Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) as an assessment tool. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:83–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florsheim P, Benjamin LS. The Structural Analysis of Social Behavior observational coding scheme. In: Kerig P, Lindahl LM, editors. Family observational coding systems: resources for systematic research. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2001. pp. 101–13. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pletcher MJ, Tice JA, Pignone M, Browner WS. Using the coronary artery calcium score to predict coronary heart disease events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1285–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reilly MP, Wolfe ML, Localio AR, Rader DJ. Coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular risk factors: impact of the analytic approach. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenny DA, Kashy DA. Cook WL Dyadic data analysis. Guilford; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus users’ guide. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications; Thusand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whisman MA, McClelland GH. Designing, testing, and interpreting interactions and moderator effects in family research. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:111–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown PC, Smith TW. Social influence, marriage, and the heart: Cardiovascular consequences of interpersonal control in husbands and wives. Health Psychol. 1992;11:88–96. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthews KA, Zhu S, Tucker DC, Whooley MA. Blood pressure reactivity to psychological stress and coronary calcification in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Hypertension. 2006;47:391–95. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200713.44895.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fewell Z, Davey Smith G, Stern JA. The impact of residual and unmeasured confounding in epidemiologic studies: a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:646–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith TW, Glazer K, Ruiz JM, Gallo LC. Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: An interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health. J Personal. 2004;72:1217–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]