Abstract

Once-daily Truvada (Emtricitabine/Tenofovir) as a method of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is one of the most promising biomedical interventions to eliminate new HIV infections; however, uptake among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men has been slow amidst growing concern in popular/social media that PrEP use will result in reduced condom use (i.e., risk compensation). We investigated demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial differences in willingness to use PrEP as well as the perceived impact of PrEP on participants’ condom use in a sample of 206 highly sexually active HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Nearly half (46.1 %) said they would be willing to take PrEP if it were provided at no cost. Although men willing to take PrEP (vs. others) reported similar numbers of recent casual male partners (<6 weeks), they had higher odds of recent receptive condomless anal sex (CAS)—i.e., those already at high risk of contracting HIV were more willing to take PrEP. Neither age, race/ethnicity, nor income were associated with willingness to take PrEP, suggesting equal acceptability among subpopulations that are experiencing disparities in HIV incidence. There was limited evidence to suggest men would risk compensate. Only 10 % of men who had not engaged in recent CAS felt that PrEP would result in them starting to have CAS. Men who had not tested for HIV recently were also significantly more likely than others to indicate willingness to take PrEP. Offering PrEP to men who test infrequently may serve to engage them more in routine HIV/STI testing and create a continued dialogue around sexual health between patient and provider in order to prevent HIV infection.

Keywords: PrEP, Gay and bisexual men, Risk compensation, PrEP acceptability, Truvada

Introduction

More than three decades into the HIV/AIDS epidemic, researchers have described our HIV prevention efforts as stalled [1]. In spite of representing between 2 and 5 % of the population [2], gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) make up an estimated 65 % of new HIV infections [3]. In recent years, incidence has plateaued among GBMSM overall; however, in some subpopulations such as GBMSM of color, it has increased dramatically [4]. In 2010, the Iniciativa Profilaxis Pre-Exposición (iPrEX) study released the first set of results from their ongoing trial of once-daily Truvada (Emtricitabine/Tenofovir) as a method of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). These initial results found PrEP to reduce the likelihood of HIV infection in GBMSM by 44 % [5]. However, further examination of the results has noted that, among those with detectable levels of the drug in their system, HIV infections were reduced by 92 % [5]. All said, PrEP remains one of the most promising biomedical interventions to eliminate new HIV infections in populations who are at high risk of contracting HIV [6]. In a simulation study, PrEP was shown to prevent 29 % of new HIV infections over a 20-year time horizon [7]. Both the CDC and WHO have recommended that GBMSM consider PrEP as part of their HIV prevention plan [8, 9]. Specifically, the CDC has recommended PrEP to GBMSM at high risk of acquiring HIV [9], whereas, WHO recommended that all GBMSM consider the use of PrEP while still continuing to use condoms [8].

Since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved PrEP for HIV prevention in the United States in 2012, popular media has indicated that awareness of PrEP has been low and roll out has been slow [6, 10, 11]. Although studies have reported that PrEP naive GBMSM are interested in using PrEP once they are educated about the HIV prevention tool [12, 13], a 2014 study reported that after educating 416 HIV-negative GBMSM about PrEP at a testing facility, only 2 (0.47 %) accepted the offer of a prescription [14]. Between January, 2011 and March 2013, only 1774 HIV-negative people in the U.S. had filled prescriptions for PrEP, many of which were women [15].

Several reasons have been proposed for the slow uptake of PrEP, though limited empirical evidence exists. Some have suggested it may be due to cost concerns [16, 17], given that an annual prescription of Truvada can exceed $12,000 for those without health insurance or prescription coverage. In addition, even for those with insurance, high copayments may also serve as a deterrent [18]. Others have suggested it may be a combination of lack of awareness that one may be an appropriate candidate for PrEP [19] coupled with the belief that PrEP is only for men who are very risky [19]. GBMSM have also expressed a concern about social stigma attached to taking PrEP—fear of what family or friends may think about the choice to take the medication [7, 20-22]. Provider-initiated barriers have also been proposed as responsible for the slow uptake [23]. To our knowledge, educational attainment is the only demographic characteristic to be associated with acceptability of PrEP. In prior research, higher educational attainment was positively correlated with PrEP acceptability [6, 24].

For providers, researchers, and among gay and bisexual communities, there is an ongoing question as to whether taking PrEP will result in GBMSM reducing their condom use [20, 25] via risk compensation (i.e., biological risks are decreased by PrEP and so behavioral risks are increased). In contrast to messages being spread via popular and social media [26], empirical data suggest the potential for risk compensation is low. For example, when a sample of GBMSM, all of whom had reported condomless anal sex (CAS), were presented with hypothetical situations about PrEP use, 35.5 % of men said they would reduce their condom use if PrEP was 80 % effective [24].

For the current study, we investigated demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial differences in willingness to use PrEP, as well as the perceived impact of PrEP on participants’ condom use. Our sample included highly sexually active gay and bisexual men—individuals who meet WHO and CDC recommendations as candidates for PrEP. To our knowledge, there are no published studies on willingness to use PrEP as well as the perceived impact of PrEP on condom use with this population. As an exploratory study, we did not have a priori hypotheses. With the continued expansion and uptake of PrEP among populations at high risk of HIV acquisition, such findings can be useful for providers and research both in terms of the characteristics associated with willingness to use PrEP, as well as perceived impact of PrEP on future condom use.

Method

Analyses for this manuscript were conducted on data from The Pillow Talk Project, a longitudinal study of highly sexually active (i.e., ≥9 male partners in 90 days) gay and bisexual men in New York City (NYC) [27]. For the purposes of this project, we operationalized highly sexually active as having at least 9 sexual partners in the 90 days prior to enrollment. This criterion was based on prior research [28-30] including a probability-based sample of urban GBMSM [31, 32] that found nine partners was two to three times the average number of sexual partners among sexually active GBMSM. By definition, every participant for the present analysis would have met eligibility criteria for the iPrEX trial, as well as CDC and WHO recommendations for starting PrEP.

Recruitment procedures have been described elsewhere [33]. In brief, we utilized a combination of strategies: (1) respondent-driven sampling; (2) Internet-based advertisements on social and sexual networking websites; (3) email blasts through New York City gay sex party listservs; and (4), active recruitment in New York City venues such as gay bars/clubs, concentrated gay neighborhoods, and ongoing gay community events.

Enrollment began in February, 2011 and closed in June, 2013. The project enrolled both HIV-negative and HIV-positive men, though the analyses for this manuscript were limited to HIV-negative men. Of the 377 men who enrolled in the project, 208 (55.2 %) were confirmed to be HIV-negative with a rapid HIV antibody test during their assessment. Two of these men were missing responses on key variables for this study; thus, the present analysis focused on the remaining 206 HIV-negative gay and bisexual men.

Participants and Procedures

Participants completed a phone-based screening interview to assess eligibility, which was defined as: at least 18 years of age; biologically male and self-identified as male; nine or more male sexual partners in the prior 90 days; self-identification as gay, bisexual, or some other non-hetero-sexual identity (e.g., queer); and daily access to the internet (which was required for a portion of the study not discussed in this manuscript). Participants who met preliminary eligibility were emailed a link to an internet-based computer-assisted self-interview (CASI), which included informed consent procedures. Men completed this one-hour online survey at home followed by an in-person baseline appointment. Final eligibility and enrollment was confirmed during the in-person appointment.

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York.

Measures

Measures used for this manuscript were taken from the baseline assessment. Using a computer-assisted survey, participants reported demographic characteristics, including sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, education, and relationship status. Participants completed the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI, α = 0.89) [34], the Temptation for Unsafe Sex Scale (α = 0.95) [34], the Safer Sex Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (α = 0.97) [20, 35], and the Decisional Balance (Pros & Cons) for Sex Without Condoms [36-38] which includes a subscale to measure perceived benefits to not using condoms (e.g., sex without a condom is more spontaneous, α = 0.86), and a subscale to measure perceived negative consequences from not using condoms (e.g., having sex without a condom could cause me to get an STD, α = 0.81). The HSDI [39] is a seven item scale divided into two sections. Both sections include the prompt “Please rate how often each item is true or how accurately it describes your sexual behavior during the last 6 months.” Section A contains five items measuring recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors. Section B consists of two items measuring distress and impairment as a result of these fantasies, urges, and behaviors. Responses (0 = Never true to 4 = Almost always true) were summed to provide a score ranging from 0 to 28. Responses of 3 or 4 are recoded as endorsement whereas 0, 1, or 2 are coded as non-endorsement. Participants were considered to have screened positive for hypersexual disorder if they endorsed at least four items in Section A and at least one item in Section B.

Sexual Behavior

During the in-person assessment, participants completed an interviewer-administered structured timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview [40, 41] which involved completing a detailed calendar of their sexual events in the 42 days (6 weeks) prior to the study visit. We generated summary scores for a variety of sexual behaviors (e.g., number of male partners, number of male serodiscordant partners, insertive anal sex without a condom (yes, no), receptive anal sex without a condom (yes, no)).

Pre-exposure Prophylaxis

Participants were presented with the following brief summary of PrEP:

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is a new biochemical strategy to prevent HIV infection. PrEP involves HIV-negative guys taking anti-HIV medications (for example, Truvada) once a day, every day to reduce the likelihood of HIV infection if they were exposed to the virus. The first clinical trial of PrEP indicated that it reduced the likelihood of HIV infection when used in combination with other preventative methods, such as condoms.

Participants then responded to a series of questions including, how likely they would be to take PrEP if it were offered to them for free (would definitely, would probably, might, would probably not, would definitely not), and how familiar they were with PrEP (dichotomized into 0 = never heard of before, 1 = heard of before). Those who said they would probably or definitely take it were coded as having a high willingness to take PrEP in these analyses (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Men were also asked if taking PrEP would influence their condom use (significantly more likely, somewhat more likely, would not change, somewhatless likely, significantly less likely). This variable was trichotomized (−1 = decrease use, 0 = no change, 1 = increase use).

Analytic Plan

In the first set of analyses, we compared men who were willing versus unwilling to take PrEP. In the second set, we compared the perceived impact of PrEP on men’s condom use (i.e., risk compensation). For both sets of analyses participants were compared based on demographic characteristics, psychosocial measures, and sexual behavior. When appropriate, Chi square, t tests, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used. Finally, we conducted a forward and backward logistic regression to determine independent associations with the belief that PrEP would reduce one’s condom use (1 = yes, 0 = no). Variables selected for the model were taken from those that were significant (p < 0.05) at the bivariate level (shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceived impact of PrEP on condom use

| Perceived impact of PrEP on my condom use |

Decrease |

No change |

Increase |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 48 |

n = 129 |

n = 29 |

||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ 2 | p | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 21 | 23.6 | 49 | 55.1 | 19 | 21.3 | - | |

| 30–39 | 17 | 28.8 | 36 | 61 | 6 | 10.2 | ||

| 40–49 | 7 | 21.9 | 23 | 71.9 | 2 | 6.3 | ||

| 50+ | 3 | 11.5 | 21 | 80.8 | 2 | 7.7 | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–39 | 38 | 25.7 | 85 | 57.4 | 25 | 16.9 | 6.49 | 0.04 |

| 40+ | 10 | 17.2 | 44 | 75.9 | 4 | 6.9 | ||

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black | 3 | 10.7 | 20 | 71.4 | 5 | 17.9 | - | |

| Latino | 4 | 17.4 | 12 | 52.2 | 7 | 30.4 | ||

| White | 32 | 25.8 | 87 | 70.2 | 5 | 4.0 | ||

| Other | 9 | 29 | 10 | 32.3 | 12 | 38.7 | ||

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-white | 16 | 19.5 | 42 | 51.2 | 34 | 29.3 | 26.00 | <0.001 |

| White | 32 | 25.8 | 87 | 70.2 | 5 | 4.0 | ||

| Income ≥ $30K | ||||||||

| No | 18 | 19.8 | 52 | 57.1 | 21 | 23.1 | 11.03 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 30 | 26.1 | 77 | 67.0 | 8 | 7.0 | ||

| 4-year college education | ||||||||

| No | 10 | 16.9 | 30 | 50.8 | 19 | 32.2 | 22.56 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 38 | 25.9 | 99 | 67.3 | 10 | 6.8 | ||

| Currently in a relationship | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 15.8 | 26 | 68.4 | 6 | 15.8 | 1.48 | 0.48 |

| Recency of last HIV test | ||||||||

| Less than 3 months | 28 | 26.7 | 60 | 57.1 | 17 | 16.2 | 3.02 | 0.55 |

| 3–6 months ago | 10 | 22.2 | 30 | 66.7 | 5 | 11.1 | ||

| Greater than 6 months | 10 | 17.9 | 39 | 69.6 | 7 | 12.5 | ||

| Anal sexual role | ||||||||

| Top or versatile top | 20 | 21.7 | 60 | 65.2 | 12 | 13 | 0.58 | 0.97 |

| Versatile | 11 | 26.2 | 25 | 59.5 | 6 | 14.3 | ||

| Bottom or versatile bottom | 17 | 23.6 | 44 | 61.1 | 11 | 15.3 | ||

| Self-identified as a barebacker | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 27.3 | 7 | 63.6 | 1 | 9.1 | – | |

| Hypersexual disorder screening inventory (HDSI) diagnosis | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 14.3 | 14 | 50.0 | 10 | 35.7 | – | |

| Sexual behavior, last 42 days (6 weeks) | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | K-W | p | post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total # male partners | 14 | 10–18 | 10 | 7–17 | 9 | 6–12.5 | 7.769 | 0.02 | A ≠ B |

| Total # male serodiscordant partnersa | 4 | 2–9 | 4 | 1–11 | 4 | 1.5–8.5 | 0.163 | 0.92 |

| Sexual behavior, last 42 days (6 weeks) | n | % | n | % | n | % | x2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal insertive, no condom | ||||||||

| No | 17 | 15.1 | 79 | 71.8 | 14 | 12.7 | 9.73 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 31 | 32.3 | 50 | 52.1 | 15 | 15.6 | ||

| Anal receptive, no condom | ||||||||

| No | 28 | 19.4 | 93 | 64.6 | 23 | 16.0 | 4.57 | 0.10 |

| Yes | 20 | 32.3 | 36 | 58.1 | 6 | 9.7 | ||

| Any condomless anal sex | ||||||||

| No | 9 | 10.1 | 67 | 75.3 | 13 | 14.6 | 15.74 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 39 | 33.3 | 62 | 53.0 | 16 | 13.7 | ||

| Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | Post hoc | |

| Temptation for unsafe sex scale, range 13–65 | 38.12 | 10.10 | 27.98 | 12.71 | 33.17 | 15.40 | 11.83 | <0.001 | A ≠ B |

| Decisional balance for sex without a condom (Pro), range 1–5 | 2.97 | 0.82 | 2.36 | 0.77 | 2.76 | 1.09 | 8.90 | <0.001 | A ≠ B |

| Decisional balance for sex without a condom (Con), range 1–5 | 3.45 | 0.74 | 3.63 | 0.90 | 3.98 | 0.84 | 3.45 | 0.03 | A ≠ C |

| Safer sex self-efficacy questionnaire, range 13–65 | 44.35 | 10.83 | 51.61 | 14.43 | 43.93 | 15.98 | 6.86 | 0.001 | B≠A, C |

K-W Kruskal-Wallace, IQR interquartile range, Mdn Median

– Chi-square cannot be interpreted, expected counts fall below 5 in one or more cells

Serodiscordant includes partners who were believed to be HIV-positive or of unknown HIV status

Results

As can be seen in Table 1, the sample was diverse with regards to race and ethnicity, employment status, and educational achievement, while a majority of the sample was gay-identified and single. Average age was 34 (SD = 11.8). Eighteen percent were currently in a relationship and two-thirds of the sample self-reported a lifetime STI diagnosis, with gonorrhea, chlamydia, and genital warts being the most common. Participants reported a median of 11 casual male partners (IQR 7 to 17) in the last 42 days (6 weeks).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| Black | 28 | 13.6 |

| Latino | 23 | 11.2 |

| White | 124 | 60.2 |

| Other | 31 | 15.0 |

| Income | ||

| <$30,000 | 91 | 44.2 |

| $30,000+ | 115 | 55.8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 83 | 40.3 |

| Part-time | 66 | 32.0 |

| Unemployed/student/disability | 57 | 27.7 |

| Education | ||

| Some high school/GED or less | 13 | 6.3 |

| Some college, associates degree, or currently in college | 46 | 22.3 |

| 4-year college degree | 84 | 40.8 |

| Graduate school | 63 | 30.6 |

| Relationship status | ||

| In a relationship (e.g., married, boyfriend, lover) | 38 | 18.4 |

| I am casually dating | 49 | 23.8 |

| I am single | 119 | 57.8 |

| Ever experienced an STI (yes) | 136 | 66.0 |

| Chlamydia | 56 | 27.2 |

| Gonorrhea | 68 | 33.0 |

| Anal/genital warts/HPV | 52 | 25.2 |

| Genital herpes (HSV1/HSV2) | 34 | 16.5 |

| Syphillis | 19 | 9.2 |

| Hepatitis C | 2 | 1.0 |

| Hepatitis B | 8 | 3.9 |

| Urethritis | 26 | 12.6 |

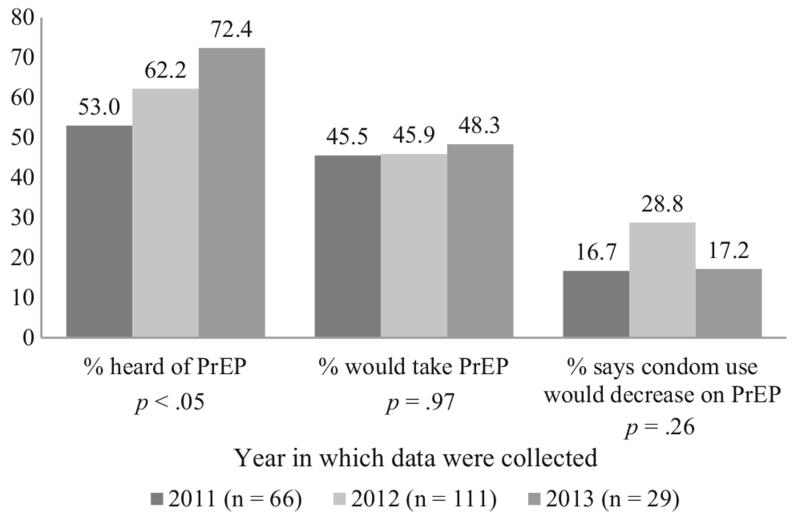

Participants’ familiarity with PrEP was significantly associated with the year in which they enrolled: nearly half (47.0 %) of participants enrolled in 2011 said they had never heard of PrEP, compared with 37.8 % among men enrolled in 2012, and only 27.6 % in 2013, Mantel–Haenszel χ2(1) = 6.06, p = 0.01; Pearson χ2(4) = 9.61, p = 0.047. However, willingness to take PrEP if it was provided for free (p = 0.97) and the perceived impact of PrEP on one’s condom use (p = 0.26) did not significantly change over time. Overall, nearly half (46.1 %) of participants said they would be willing to take PrEP if it was provided for free. And, 23.1 % said they believed it would decrease their condom use, 62.6 % said their condom use would stay the same, and 14.1 % said they would increase their condom use if on PrEP. Six men (2.9 %) said they had taken PrEP at one point in their lives (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Changes in PrEP familiarity, uptake, and the perceived impact of PrEP on condom use between 2011 and 2013

Table 2 displays factors associated with willingness to take PrEP if it were provided at no cost and Table 3 reports on the perceived impact of PrEP on condom use. Willingness to take PrEP was not significantly associated with age, race/ethnicity, income, being in a relationship, anal sexual role (e.g., top, bottom, versatile), self-identifying as a barebacker, temptations for CAS, perceptions of the drawbacks of CAS, self-efficacy for condom use, or the number of male sex partners in the last 42 days. Men who indicated willingness to take PrEP perceived significantly greater benefits of engaging in CAS. Compared with men who indicated low willingness to take PrEP, a significantly larger proportion of men willing to take PrEP last tested for HIV more than 6 months ago, reported recent receptive CAS, and screened positive for hypersexual disorder. Compared with men who indicated low willingness to take PrEP, a significantly smaller proportion of men who indicated willingness to take PrEP had a college education. Although not significant (p = 0.06), there was a trend between perceived impact of PrEP on condom use and willingness to start PrEP—in total, 65.5 % of men who said PrEP would increase their condom use expressed willingness to take PrEP compared with only 47.9 % of those who felt that PrEP would decrease their condom use and 41.1 % of men who felt that PrEP would have no impact on their condom use.

Table 2.

Willingness to take PrEP if it were free

| High willingness to take PrEP if it were free | Noa |

Yesb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 111 |

n = 95 |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | χ 2 | p | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 | 45 | 50.6 | 44 | 49.4 | 1.61 | 0.66 |

| 30–39 | 33 | 55.9 | 26 | 44.1 | ||

| 40–49 | 20 | 62.5 | 12 | 37.5 | ||

| 50+ | 13 | 50 | 13 | 50 | ||

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 17 | 60.7 | 11 | 39.3 | 2.06 | 0.56 |

| Latino | 10 | 43.5 | 13 | 56.5 | ||

| White | 69 | 55.6 | 55 | 44.4 | ||

| Other | 15 | 48.4 | 16 | 51.6 | ||

| Income ≥ $30K | ||||||

| No | 44 | 48.4 | 47 | 51.6 | 2.07 | 0.16 |

| Yes | 67 | 58.3 | 48 | 41.7 | ||

| 4-year college education | ||||||

| No | 24 | 40.7 | 35 | 59.3 | 5.80 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 87 | 59.2 | 60 | 40.8 | ||

| Currently in a relationship | ||||||

| Yes | 22 | 57.9 | 16 | 42.1 | 0.30 | 0.58 |

| Recency of last HIV test | ||||||

| Less than 3 months | 66 | 62.9 | 39 | 37.1 | 7.09 | 0.03 |

| 3–6 months ago | 21 | 46.7 | 24 | 53.3 | ||

| Greater than 6 months | 24 | 42.9 | 32 | 57.1 | ||

| Anal sexual role | ||||||

| Top or versatile top | 51 | 55.4 | 41 | 44.6 | 0.16 | 0.92 |

| Versatile | 22 | 52.4 | 20 | 47.6 | ||

| Bottom or versatile bottom | 38 | 52.8 | 34 | 47.2 | ||

| Self-identified as a barebacker | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 45.5 | 6 | 54.5 | 0.32 | 0.56 |

| Hypersexual disorder screening inventory (HDSI) diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 32.1 | 19 | 67.9 | 6.16 | 0.01 |

| Perceived impact of PrEP on my condom use | ||||||

| Decrease | 25 | 52.1 | 23 | 47.9 | 5.77 | 0.06 |

| No change | 76 | 58.9 | 53 | 41.1 | ||

| Increase | 10 | 34.5 | 19 | 65.5 | ||

| Sexual behavior, last 42 days (6 weeks) | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | U | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total # male partners | 10 | 7–18 | 11 | 8–17 | 5476 | 0.63 |

| Total # male serodiscordant partnersc | 4 | 2–10 | 4 | 1–9 | 5101 | 0.69 |

| n | % | n | % | χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual behavior, last 42 days (6 weeks) | ||||||

| Anal insertive, no condom | ||||||

| No | 60 | 54.5 | 50 | 45.5 | 0.04 | 0.84 |

| Yes | 51 | 53.1 | 45 | 46.9 | ||

| Anal receptive, no condom | ||||||

| No | 85 | 59 | 59 | 41 | 5.1 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 26 | 41.9 | 36 | 58.1 | ||

| Any condomless anal sex | ||||||

| No | 51 | 57.3 | 38 | 42.7 | 0.74 | 0.39 |

| Yes | 60 | 51.3 | 57 | 48.7 | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temptation for unsafe sex scale, range 13–65 | 30.00 | 13.10 | 32.3 | 13.30 | 1.31 | 0.19 |

| Decisional balance for sex without a condom (Pro), range 1–5 | 2.41 | 0.84 | 2.73 | 1.00 | 2.46 | 0.02 |

| Decisional balance for sex without a condom (Con), range 1–5 | 3.56 | 0.85 | 3.72 | 0.89 | 1.29 | 0.20 |

| Safer Sex Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, range 13–65 | 49.25 | 14.76 | 48.36 | 13.81 | 0.45 | 0.66 |

U Mann-Whitney U, IQR interquartile range, Mdn Median

“Might,” “Probably not,” “Definitely not”

“Probably would,” “Definitely would”

Serodiscordant includes partners who were believed to be HIV-positive or of unknown HIV status

The perceived impact of PrEP on condom use was not significantly associated with being in a relationship, recency of HIV testing, hypersexual disorder, or anal sexual role. It was associated with age, race/ethnicity, and income (see Table 3). Men who believed PrEP would decrease their condom use also reported significantly higher levels of temptation to engage in CAS and higher perceived benefits to engaging in CAS, and lower perceived drawbacks to engaging in CAS. Compared to men who felt PrEP would have no impact on their condom use, men who believed PrEP would decrease their condom use also reported a greater number of male partners. Furthermore, one-third of men who engaged in recent CAS believed that PrEP would decrease their condom use, compared to only 10 % of men who did not report recent CAS. Men who perceived that PrEP would have no impact on their condom use reported significantly higher levels of self-efficacy for condom use.

Finally, we conducted both forward and backward logistic regression to determine independent associations with the belief that PrEP would reduce one’s condom use (1 = yes, 0 = no). Variables selected for the model were taken from those that were significant (p < 0.05) at the bivariate level (shown in Table 3). Both models converged on the same two variables: (1) CAS in the prior 42 days (AOR = 2.96, 95 % CI 1.82–6.85), and (2) increased scores on the Temptation for Unsafe Sex Scale (AOR = 1.04, 95 % CI 1.01–1.07).

Discussion

Pillow Talk is a study of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men—individuals who, by definition, meet WHO and CDC criteria/guidelines for PrEP treatment [9, 19]. In this study, nearly half of men said they would be willing to take PrEP if it were offered at no cost to them. Although men willing to take PrEP reported similar number of male partners in the prior 6 weeks, they had higher odds of reporting recent receptive CAS. In essence, those already at high risk of contracting HIV were significantly more willing to take PrEP. These men also had higher odds of screening positive for hypersexual disorder, suggesting that they might be ideal targets for offering PrEP, as uptake among these men may be higher.

This study found marked increase in knowledge of PrEP over time consistent with historical events (e.g., the release of iPrex results in 2011, FDA approval in 2012, and social media campaigns both for and against PrEP in 2013) [20-22]. Interestingly, although awareness of PrEP increased over time, willingness to use PrEP and the perceived impact of PrEP on condom use did not change in this study. These findings suggest that although awareness of PrEP is increasing, willingness to use PrEP is not. It may be that stagnant willingness to start PrEP could be a result of individuals not recognizing that they would be appropriate candidates to start PrEP [19], or stigma attached to using PrEP [42]. Likewise, the perceived impact of PrEP on condom use did not change over time. This too suggests that although awareness of PrEP is increasing, this increased knowledge about PrEP has not altered men’s attitudes about condom use.

Neither age, race/ethnicity, nor income were associated with willingness to take PrEP, suggesting equal PrEP acceptability among GBMSM subpopulations that are experiencing disparities in HIV incidence (e.g., younger men, men of color). That being said, the question assessing willingness to take PrEP was phrased regarding PrEP if it was available for free. Although many US insurance plans, including Medicaid, cover Truvada and, at the moment, Gilead (the manufacturer of Truvada) provides a coupon that will cover much—if not all—of a person’s copayment (gileadcopay.com). It is unclear how many men in this study may have been dissuaded from starting PrEP due to cost concerns. The reality is that PrEP may effectively be free or low cost for many individuals in the US; however, it remains important to ensure individuals are properly engaged in primary care and are aware of the avenues by which PrEP is available to them at low cost or for free.

Men with less than a college education were more likely than others to consider taking PrEP, which is inconsistent with prior research [6, 24]. It may be that those with more education are reading more about PrEP and have greater concerns regarding efficacy, adherence, and stigma. Alternately, this may be a result of the unique nature of the population from which we sampled (highly sexually active). In either event, our findings highlight the need to investigate the association between education and willingness to use PrEP. As a biomedical strategy, PrEP involves navigating health care systems (e.g., primary care, testing for HIV and kidney function, prescription coverage) coupled with behavioral methods of HIV and STI prevention (e.g., condom use). Level of education is related to health literacy [37] and thus should be monitored with regard to PrEP uptake, adherence, and effectiveness.

Men who had not tested recently were also more likely to indicate willingness to take PrEP than others. Present guidelines for PrEP treatment indicate that providers retest for HIV every three to four months before they renew a patient’s prescription, along with providing behavioral risk reduction support, assessment for both side effects and STI symptoms, and medication adherence counseling [9]. Offering PrEP to men who test infrequently may serve to engage them more in routine HIV and STI testing, create a continued dialogue around sexual health between patient and provider, and prevent HIV infection.

In popular and social media there has been significant debate about the impact of PrEP on CAS, often suggesting that men’s condom use will decrease as a result of initiating PrEP [20, 21, 43]. In contrast to these hypotheses regarding the potential for risk compensation, this study builds on prior work refuting risk compensation. For example, a previous study of GBMSM reporting CAS in NYC [24], found that only 35.5 % of men would reduce their condom use if PrEP was 80 % effective, and only 23.3 % of men in our study believed their condom use would decrease. Further, our results suggest that only 10 % of men who had not engaged in recent CAS felt that PrEP would result in them starting to have CAS. That is, 90 % of men who abstained from CAS felt their condom use would remain the same or increase.

Importantly, those who felt their risk behaviors may increase as a result of PrEP were overwhelmingly those who were already engaging in behaviors that put them at risk for HIV. This suggests that PrEP may be a more effective HIV prevention option for these men regardless of potential increases in CAS given the already inconsistent nature of their condom use. With adequate medication adherence, these men would be protected both during times when they are already engaging in risk behavior, as well as during any potential additional risk behavior resulting from PrEP initiation, whereas they are presently completely unprotected during all acts of risk behavior (hold for viral suppression among any undetectable HIV-positive partners). To protect these men from contracting and transmitting STIs, it would be additionally vital to regularly test and treat for the full range of STIs, (including blood, urethral, rectal, and pharyngeal screening), as well as vaccinate for HPV and hepatitis A and B. Further, it remains unknown as to whether the presence of an STI—which serves as a highly effective route for HIV to pass between partners—would decrease the ability of PrEP to prevent seroconversion by virtue of greater exposure to the virus at a given time.

Our study found that the perceived impact of PrEP on condom use was associated with several important demographic characteristics including age, race, income, and education. With the exception of age, the associations observed with other demographic characteristics suggest that the most vulnerable men would not change their condom use or, in fact, would increase it. This includes men of color, men with lower income, and men with less than a college education. We did find, however, that men under the age of 40 were more likely than those over 40 to say that their condom use would decrease. This may be a generational effect related to the history of the HIV epidemic. Men over 40 came of age during the height of the epidemic, while those under 40 came of age at a time when it was known how HIV was transmitted and effective treatment options were available [44].

Limitations

The results of this study should be understood in light of their limitations. To be eligible for the Pillow Talk study, men had to report at least nine male partners in the prior 90 days. This sample represents, by definition, ideal targets for PrEP; however, these men do not represent all gay and bisexual men. We used a variety of non-probability methods to recruit participants and, although respondent-driven sampling was among our methods, we lacked statistical power to assess for homophily or differences by recruitment method. Some measures were collected via online survey, which allowed men to complete the survey from the comfort of their homes and on their own schedule; however, we cannot know what types of distractions might have been drawing their attention away from the survey while they completed it. Data used in this analysis were cross-sectional, and behavioral measures were captured via the TLFB interview, which has demonstrated strong reliability and validity with a variety of populations. However, as a face-to-face interview, there is the potential for bias due to socially desirable responses. We do not have data on reasons why individuals were unwilling to go on PrEP and our findings indicate the prevalence is large enough to warrant further consideration, perhaps through qualitative methods like semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups. The results of this study concerned hypothetical PrEP initiation. As PrEP continues to diffuse as a new prevention strategy, it is important to continue to investigate how gay and bisexual men who represent ideal targets for PrEP perceive its impact on their own sexual behavior.

Conclusion

In a sample of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men, we found that knowledge of PrEP increased markedly between 2011 and 2013, however willingness to use PrEP as well as the perceived impact of PrEP on one’s own sexual behavior did not change. Willingness to use PrEP was not significantly associated with a number of key demographic characteristics, suggesting that GBMSM subpopulations that are disproportionally impacted by HIV (e.g., young men of color) would be equally likely to consider PrEP. Nearly two-thirds of participants believed that their condom use would not change were they on PrEP, and a minority felt their condom use would decrease. Because being on PrEP requires one to see their care provider every 3 months, this can serve as an important opportunity to engage men in sexual health discussions and interventions to prevent onward STI transmission. Those who felt their risk behaviors may increase as a result of PrEP were overwhelmingly those who were already engaging in some degree of HIV transmission risk behavior. This suggests that PrEP may be a highly effective HIV prevention option for these men regardless of potential increases in CAS given their ongoing inconsistent condom use.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a Research Grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH087714; Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Pillow Talk Research Team, particularly John Pachankis, Ruben Jimenez, Brian Mustanski, Demetria Cain, and Sitaji Gurung. We would also like to thank CHEST staff who played important roles in the implementation of the project: Chris Hietikko, Joshua Guthals, Chloe Mirzayi, Kailip Boonrai, as well as our team of research assistants, recruiters, and interns. Finally, we thank Chris Ryan, Daniel Nardicio, and Stephan Adelson and the participants who volunteered their time for this study.

Contributor Information

Christian Grov, The Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies & Training (CHEST), New York, NY, USA; Department of Health and Nutrition Sciences, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York (CUNY), Brooklyn, NY, USA; CUNY School of Public Health, New York, NY, USA.

Thomas H. F. Whitfield, The Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies & Training (CHEST), New York, NY, USA; Health Psychology and Clinical Science Doctoral Program, The Graduate Center of CUNY, New York, NY, USA

H. Jonathon Rendina, The Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies & Training (CHEST), New York, NY, USA.

Ana Ventuneac, The Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies & Training (CHEST), New York, NY, USA.

Jeffrey T. Parsons, The Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies & Training (CHEST), New York, NY, USA; Department of Psychology, Hunter College of City University of New York (CUNY), 695 Park Ave, New York, NY 10065, USA

References

- 1.Stall R, Duran L, Wisniewski SR, et al. Running in place: implications of HIV incidence estimates among urban men who have sex with men in the United States and other industrialized countries. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:615–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9509-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill D. [Accessed 10 Aug 2014];PrEP yourself: making better sense of the pre-exposure prophylaxis debate. 2014 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/daniel-oneill/prep-yourself-making-better-sense-of-the-pre-exposure-prophylaxis-debate_b_5203299.html.

- 3.CDC Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauermeister J. Concerns regarding PrEP accessibility and afordability among YMSM in the United States; 141st APHA Annual Meeting; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger CL. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(4):248–54. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DK, Toledo L, Smith DJ, Adams MA, Rothenberg R. Attitudes and Program Preferences of African-American Urban Young Adults About Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(5):408–21. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holt M, Murphy DA, Callander D, et al. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and the likelihood of decreased condom use are both associated with unprotected anal intercourse and the perceived likelihood of becoming HIV positive among Australian gay and bisexual men. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:258–63. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC [Accessed 17 May 2014];Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States-2014 A clinical practice guideline. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf.

- 10.CDC [Accessed 10 Aug 2014];HIV among african americans. 2014

- 11.WHO [Accessed 10 Oct 2014];WHO: People most at risk of HIV are not getting the health services they need. 2014 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/key-populations-to-hiv/en/

- 12.Kirby T, Thornber-Dunwell M. Uptake of PrEP for HIV slow among MSM. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):399–400. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler J, Myers JE, Nucifora KA, Mensah N, Toohey C, Khademi A, Cutler B, Braithwaite RS. Evaluating the impact of prioritization of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis in New York City. AIDS. 2014;28(18):2683–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King H, Keller S, Giancola M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis accessibility research and evaluation (PrEPARE Study) AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1722–5. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0845-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee S-J, Leibowitz AA. Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1136–45. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy S. [Accessed 15 Oct 2014];Truvada for PrEP: Experts Weigh In on the Newest Way to Prevent HIV/AIDS. 2014 http://www.healthline.com/health-news/hiv-truvada-for-hiv-prevention-experts-weight-in-020714#2.

- 17.Marcus JL, Glidden DV, Mayer KH, et al. No evidence of sexual risk compensation in the iPrEx trial of daily oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade Taylor S, Mayer K, Elsesser S, Mimiaga M, O’Cleirigh C, Safren S. Optimizing content for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) counseling for men who have sex with men: perspectives of PrEP users and high-risk PrEP naïve men. AIDS Behav. 2013;18(5):871–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0617-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallagher T, Link L, Ramos M, Bottger E, Aberg J, Daskalakis D. Self-perception of HIV risk and candidacy for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men testing for HIV at commerical sex venues in New York City. LGBT Health. 2014;1:1–7. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truvada Crary D. [Accessed 9 Dec 2014];HIV Prevention Drug, Divides Gay Community. 2014 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/07/truvada-gay-men-hiv_n_5102515.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendoza J. [Accessed 9 Dec 2014];HIV pill. Progress or setback? 2014 http://www.globalpost.com/dispatches/globalpost-blogs/global-pulse/WHO-rec-revives-HIV-debate.

- 22.Press TA. [Accessed 9 Dec 2014];Divide over HIV prevention drug Truvada persists. 2014 http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/04/06/gay-men-divided-over-use-of-hiv-prevention-drug/7390879/

- 23.Duran D. [Accessed 22 Oct 2014];Truvada Whores? 2014 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-duran/truvada-whores_b_2113588.html.

- 24.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(5):548–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e19a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirby T, Thornber-Dunwell M. Uptake of PrEP for HIV slow among MSM. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):399–400. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duran D. [Accessed 14 Mar 2014];Truvada Whores? Huffington Post. 2012 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-duran/truvada-whores_b_2113588.html.

- 27.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Cook KF, Grov C, Mustanski B. A psychometric investigation of the hypersexual disorder screening inventory among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men: an item response theory analysis. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3088–101. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsons JT, Bimbi DS, Halkitis PN. Sexual compulsivity among gay/bisexual male escorts who advertise on the Internet. Sex Addict Compuls. 2001;8:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, DiMaria L, Wainberg ML, Morgenstern J. Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37(5):817–26. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(4):940–9. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:939–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2002;96(11):1589–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. The role of maladaptive cognitions in hypersexuality among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(4):669–83. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, Garnett GP, Dybul MR, Piot PK. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: a multinational study. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Bimbi D, Borkowski T. Perceptions of the benefits and costs associated with condom use and unprotected sex among late adolescent college students. J Adolesc. 2000;23(4):377–91. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13(1):39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heinrich C. Health literacy: the sixth vital sign. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24(4):218–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells BE, Golub SA, Parsons JT. An integrated theoretical approach to substance use and risky sexual behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:509–20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kafka MP. Hypersexual disorder: a proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback user’s guide. Alcohol Research Foundation; Toronto: 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parsons JT, Huszti HC, Crudder SO, Rich L, Mendoza J. Maintenance of safer sexual behaviours: evaluation of a theory-based intervention for HIV seropositive men with haemophilia and their female partners. Haemophilia. 2000;6(3):181–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bauermeister J, Meanley S, Pingel E, Soler J, Harper G. PrEP awareness and perceived barriers among single young men who have sex with men. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(7):520–7. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140129100411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dean E. The new HIV threat: young gay men who missed out on the shocking public health campaign of the 1980 s are worryingly vulnerable to HIV. Nurs Stand. 2014;28(23):24. doi: 10.7748/ns2014.02.28.23.24.s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]