Abstract

Cardiovascular medicine has evolved rapidly in the era of genomics with many diseases having primary genetic origins becoming the subject of intense investigation. The resulting avalanche of information on the molecular causes of these disorders has prompted a revolution in our understanding of disease mechanisms and provided new avenues for diagnoses. At the heart of this revolution is the need to correctly classify genetic variants discovered during the course of research or reported from clinical genetic testing. This review will address current concepts related to establishing the cause and effect relationship between genomic variants and heart diseases. A survey of general approaches used for functional annotation of variants will also be presented.

Keywords: genetic testing, genes, mutation, polymorphism

Many rare and common diseases affecting the cardiovascular system occur because of genetic susceptibilities arising from variation in individual genes or through combinations of multiple genomic variants. Research and clinical practice have been impacted greatly by this concept in the era of genetic and genomic medicine. Whether one is seeking to discover the molecular basis for a disease in a research setting or trying to interpret results from a clinical genetic test, predicting the phenotypic effect of genetic variation has emerged as a formidable challenge with many evolving solutions. This review will summarize modern conceptual and technical approaches to demonstrating genetic causality in a broad context. Understanding these approaches will contribute to improving use of genetic information in clinical practice and hone the interpretation of genomic data in the research setting for both monogenic and complex genetic disorders of the cardiovascular system.

Approaches to genetic discovery in monogenic disorders

Strategies for identifying the genetic determinants of disease susceptibility have evolved considerably during the past quarter century. For gene discovery in monogenic (Mendelian) disorders, pedigree-based linkage analysis and positional cloning strategies were once the mainstays of human genetics. However, pedigree-based methods are especially challenging for cardiovascular disease where family size may be limited because of early lethality. Further clouding genetic analysis of many cardiovascular diseases is autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance or variable expressivity. Today, these linkage-based methods are used increasingly less owing to the revolution in next-generation DNA sequencing and the emergence of whole-exome (e.g., sequencing all coding exons within a genome) and whole-genome sequencing as powerful methods to discover disease-causing mutations.1 Next-generation sequencing has created a paradigm-shift in the scale and complexity of human genetic studies enabling successful studies in small families or even single individuals with rare disorders and discovery of novel disease-causing genes at much lower cost per nucleotide than conventional methods.1,2

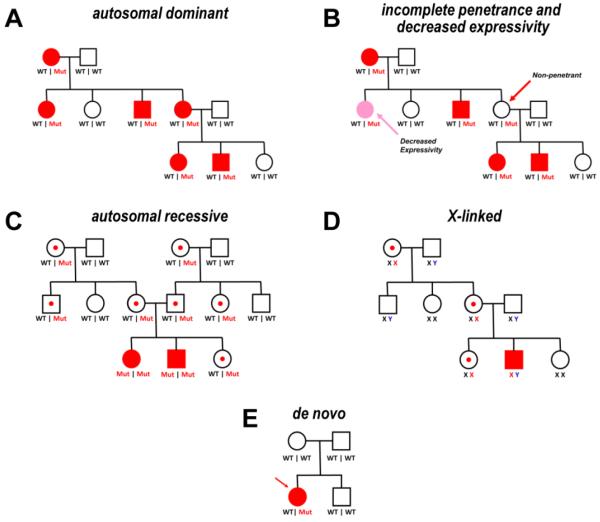

Despite these incredible technical advances, basic pedigree analysis, including the adjudication of phenotype among individuals in a family, remains critically important for assessing disorders with tractable patterns of inheritance such as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and X-linked. Indeed, the best genetic evidence supporting causality is the co-segregation of a putative mutation with the trait or phenotype in a multiplex (i.e., multiple affected members), multigenerational family tree (Fig. 1A). A positive family history can also significantly enhance the probability that genetic testing will uncover potentially causative variants as illustrated for familial cardiomyopathy.3 However, there are important caveats about co-segregation. In particular, incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity, which are the rule for most inherited forms of cardiovascular disease, confound interpretation of segregation data. The phenomenon of incomplete penetrance refers to the observation that not all individuals inheriting a presumed disease-causing mutation have equal likelihood of having the clinical phenotype (Fig. 1B). Variable expressivity refers simply to variation of phenotype severity or other types clinical heterogeneity within or among families with similar gene mutations. Incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity are common in autosomal dominant traits and current wisdom posits the existence of modifiers in the form of environmental, genetic and epigenetic factors to partly explain these phenomena.4 Another consideration in assessing segregation is that the larger the family, the greater the chance that additional rare variants may be found within the pedigree. The marked genetic heterogeneity underlying inherited cardiovascular diseases lends itself to the compounded problem that there may often be more than one pathological variant in large families.5

Fig. 1. Example pedigrees illustrating Mendelian inheritance and co-segregation.

(A) A pedigree illustrating autosomal dominant transmission of a trait. Red symbols represent family members with the trait ("affected"). Genotypes are given beneath each pedigree symbol to indicate presence of wildtype (WT) or mutant (Mut) alleles. (B) Same pedigree as in (A) modified to illustrate incomplete penetrance (e.g., presence of mutant allele in a phenotypically unaffected person) and decreased expressivity (e.g., presence of mutation but with less severe disease). (C) Pedigree illustrating autosomal recessive inheritance. Open symbols with a central red dot represent unaffected heterozygous mutation carriers. (D) Pedigree illustrating X-linked inheritance. Genotypes are given beneath each pedigree symbol to indicate presence of wildtype (black X, blue Y) or mutant (red X) sex chromosomes. (E) Pedigree illustrating occurrence of a de novo mutation.

Genetic discovery in complex traits

Within the past 10 years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become the main approach to map loci conferring risk for common, genetically complex diseases.6 This approach relies on association between genetic loci and phenotype with no underlying assumption of “identity by descent” as in the case of monogenic disorders. In GWAS, the region of association may be marked by multiple common variants, shared across the population but not by inheritance. Because of this experimental design, phenotypic effects of variants or genomic regions identified by GWAS are typically small.

In Mendelian disorders, rare genetic variants confer a major portion of disease risk making it feasible to construct a tighter genotype-phenotype relationship than what is seen with GWAS. Historically, co-segregation of a pathogenic variant with a clinical phenotype was viewed as evidence of causality. Although the presence of pathogenic variants was highly meaningful for predicting disease in a given family, the rare nature of these genetic variants made their use across the population highly limited. By contrast, GWAS was implemented based upon the “common disease-common variant” hypothesis that proposed a major portion of risk for a common disease in populations is conferred by a limited number of common (i.e., minor allele frequency > 5%) genomic variants.6 A competing theory, the common disease-rare variant hypothesis, which posits multiple rare variants confer risk for common diseases, is gaining traction with more widespread use of next-generation DNA sequencing technology.

Importantly, association of a genomic variant with a phenotype, even one that is highly statistically significant, does not imply a direct causal relationship. In most cases, variants used for assessing association were selected based upon minor allele frequencies in reference populations and not because any intrinsic functional effect conferred by the nucleotide change. The variant functionally responsible for the phenotype in question may be in linkage disequilibrium, located at some physical distance from the "marker" variant (linkage disequilibrium refers to a phenomenon in populations in which alleles at two or more loci are associated more often than is expected by chance). Within a locus, there may be multiple markers that show tight linkage or association to the phenotype and the genetic intervals between these multiple markers are not identical across populations. In GWAS, imputation is used to infer genetic markers that were not genotyped to provide missing data. Imputation does not consider rare variation in populations and will miss this contribution to inheritance. Inherent in these observations of genetic variation is the general view that common variation is evolutionarily older than rare variation.7 Genetic variation may occur within coding and noncoding regions of the genome, but in general, coding region variation is more readily interpretable than noncoding genetic variation.

Classification of gene variants

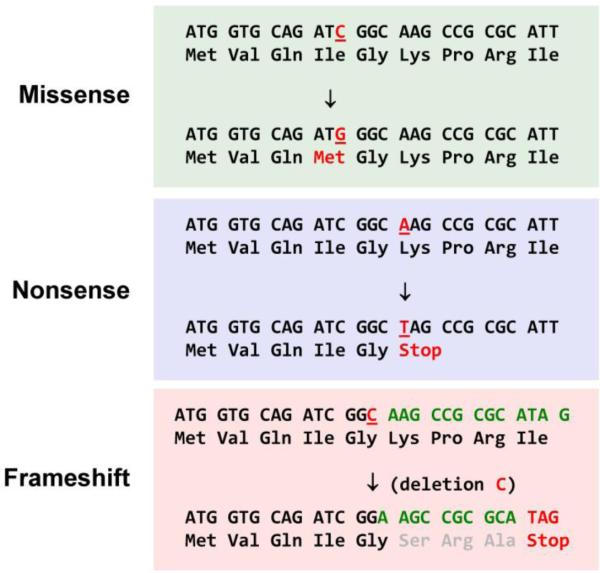

An important step in assessing genetic causality is the classification of gene variants and to assign a likelihood of pathogenicity. Clinical genetic testing laboratories use carefully defined schema to categorize sequence variation to enable concise language for reporting test results. A typical reporting framework was recommended by the American College of Medical Genetic (ACMG) Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee and includes six interpretative categories of variants to standardize laboratory reporting of genetic test results (Fig. 2).8 Genetic testing laboratories may deploy derivatives of this classification scheme for describing the likelihood of variant pathogenicity (e.g., benign, likely benign, VUS, likely pathogenic, pathogenic).

Fig. 2. Classification scheme for genetic variants.

The likelihood of pathogenicity according to a scheme proposed by the American Board of Medical Genetics8 is illustrated as a spectrum from most likely (pathogenic) to least likely (benign) pathogenic. A large category in the center ("variants of unknown significance) represents variants that cannot be easily classified.

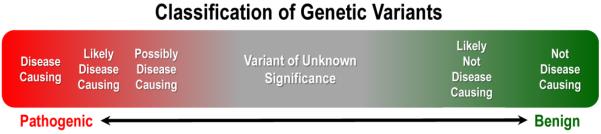

Some features of nucleotide variation offer simple clues as to whether a specific change will affect the structure, function or expression of an encoded protein. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions or deletions (indels) that introduce premature stop codons (nonsense mutation), reading frameshifts or alter bases essential for correct pre-mRNA splicing (splice site mutations) are generally considered to have high likelihood of disrupting protein function (Fig. 3). In some cases, premature truncations can cause loss of function (LOF), however in others, depending on expression of the truncated protein, premature truncations can cause gain-of-function or dominant-negative activity. Such variants will often be classified as pathogenic by virtue of their predicted effect to truncate proteins. By contrast, SNVs that do not alter the coding potential of the gene (silent or synonymous SNVs) will generally be considered functionally benign unless they are predicted to disrupt splicing. However, SNVs or small indels predicted to cause amino acid substitutions (missense or nonsynonymous) or in-frame insertions/deletions cannot be easily categorized in terms of their functional effects. Predicting the effect of missense variants increasingly relies on a multipronged approach that relies on population-based frequency, evidence such as co-segregation with a phenotype and/or experimental demonstration of altered protein function. Depending on the outcomes of these additional analyses, missense variants can be classified along a spectrum from pathogenic to benign.

Fig. 3. Common types of nucleotide sequence variants.

Three common types of single nucleotide variants that occur within protein coding regions of genes are illustrated. Missense or nonsynonymous variants are those predicted to result in an amino acid change in the encoded protein. Nonsense variants induce premature "stop" codons predicted to result in a truncated protein product. Frameshift variants in which there is an insertion or deletion of a number nucleotides that is not a multiple of 3 will cause disruption of the protein coding sequence and often lead to a premature stop codon.

Because of the comprehensive nature of exome or genome sequencing, such approaches may uncover incidental variants, some of which may be medically actionable and unrelated to the primary disorder that prompted genetic testing. The American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) Working Group on Incidental Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing has recommended that clinical genetic testing laboratories performing exome and genome sequencing seek and report on mutations in 57 known disease-associated genes; notably more than half of these genes (30 of 57) relate to inherited cardiovascular disorders.9,10 The remaining "actionable" genes are primarily those linked to inherited cancer syndromes. These recommendations were amended recently by ACMG to suggest that patients be given the opportunity to "opt out" of the analysis of medically actionable genetic variants at the time samples are sent for initial testing.11 Additional variants in genes potentially related to the phenotype for which testing was sought could represent modifier alleles, but this is extremely challenging to deduce from a single subject or small families.

Value of population allele frequency in assigning pathogenicity

Allele frequency is helpful but alone is insufficient to classify genetic variants. Single gene disorders like inherited cardiomyopathies or the long QT syndrome (LQTS) occur in less than 1 in 500 individuals. Therefore, variants with minor allele frequencies greater than 1% in the general population are generally considered to be benign for these disorders. Rare variants with minor allele frequency much less than 1% are considered to have higher likelihood of pathogenicity.12 Ultra-rare variants, sometimes referred to as private variation, are those not observed in any databases of population genome variation. However, with the expansion of large sequence databases, along with their increasing diversity, it is not unusual for private variants to now be found in very low frequency in databases.

Because of these expanding databases, reclassification of variants is now occurring.13 Pathogenic variants may be reclassified to likely pathogenic or in some cases to variants of unknown significance. A higher than expected frequency of previously reported and predicted pathogenic variation was observed in the 1000 Genome project for the MYH7, MYBPC3 and TTN genes.14,15 Similarly, variants previously reported as pathogenic for LQTS and Brugada syndrome were found at higher than expected frequency in the 1000 Genomes project.16,17 The expansion of public databases with the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project and now the Exome Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org) that represents an amalgam of sequenced exomes further supports these findings.18-20

With larger population surveys of genome variation, it is now clear that nonsense, frameshift and splice site mutations exist in healthy individuals Recent analyses of genome data indicate that all humans carry ~100 deleterious variants including some that are homozygous and others that are known to be disease-causing.21,22 Other studies have demonstrated that certain populations such as the Finnish harbor a higher frequency of heterozygous and homozygous LOF variants.23 Whether there is compensatory genetic variation that offsets these deleterious mutations is not known. Alternatively, it is possible that pathogenic mutations require additional undefined enhancing mutations to fully express as pathogenic.

Rare de novo mutations are a unique subset of potentially pathogenic variants in genes responsible for monogenic disorders that also present challenges for interpretation in genetically complex traits. In the proper setting, such as examining candidate genes or evaluating findings from exome/genome sequencing, discovery of a de novo mutation in a gene or pathway having plausible biological involvement in disease pathogenesis offers a strong case. Further support for genetic causality is provided by discovery of additional mutations in unrelated families having the same phenotype. This is exemplified by the discovery of de novo calmodulin gene mutations in unrelated probands with early onset cardiac arrhythmia susceptibility.24,25

In silico approaches to functional variant annotation

Computational strategies are evolving to help predict the potential effects of genetic variants on protein function in the research setting. Two of the more widely used methods are PolyPhen-2 and SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant). SIFT relies on protein sequence homology to assess the likelihood that a position-specific amino acid substitution will be damaging based on the premise that important residues will be conserved in the protein family throughout evolution.26,27 SIFT was originally developed using prokaryotic gene mutation data, but was later tested on a large set of annotated human mutation data. PolyPhen-2 uses protein sequence-based and structure-based features to make predictions.28 Another approach (Evolutionary Diagnosis [EvoD]) featuring statistical models based on evolutionarily weighted training data has been suggested to offer improved predictive power.29 Newer algorithms are emerging,30,31 but no particular algorithm appears superior to all others.32 It has been suggested that combinations of algorithms may offer better specificity. Disease-specific variant effect predictors may have better performance.33 Importantly, while some of these algorithms have been tested against known mutations, few have incorporated experimental modeling into these in silico prediction models.32,34

Experimental evidence of pathogenicity

Experimental approaches can assist in functional annotation of genetic variants and help nudge the interpretation toward or away from a pathogenic category, and this may be particularly helpful for classifying variants of unknown significance.35 Functional annotation is easier for some genes than others depending on the availability of in vitro and in vivo models. For example, mutations in genes encoding ion channel subunits that are associated with congenital arrhythmia susceptibility can be functionally investigated using heterologous expression coupled with cellular electrophysiological methods (e.g., patch-clamp recording). While such methods are considerably time and labor intensive, newer automated electrophysiology platforms offer promise to remove the recording step as a bottleneck and provide a more consistent method of validation. Additional strategies to assess proper trafficking of proteins to the plasma membrane have also been applied in some of the genetic variants responsible for the channelopathies such as type 2 long-QT syndrome caused by mutations in KCNH2 (encoding the HERG potassium channel). Because many pathogenic mutations disrupt HERG trafficking to the plasma membrane, biochemical strategies that assess cell surface expression or provide evidence of mature post-translational processing have been used to evaluate pathogenicity of missense mutations.36 A major challenge inherent to these approaches is the difficultly in controlling gene expression levels to avoid over-expression artifacts and to more closely approximate physiological conditions.

Modeling human mutations in experimental animals such as mice offers opportunities to determine the biological effect of specific variants in vivo. While such methods are extraordinarily powerful, they are excessively time, labor and cost intensive and hence are impractical for annotating large numbers of variants. The use of zebrafish may represent a compromise between cost and throughput as illustrated by the work of den Hoed and colleagues.37 In this study to determine genomic loci associated with resting heart rate in more than 180,000 subjects, 14 new loci were identified. Genes found within these genomic loci were then interrogated in Drosophila and zebrafish. Changes in heart rate were observed for 20 genes within 11 of the loci by reducing or ablating gene expression. Zebrafish can also be used to interrogate the physiological effects of cardiac ion channel variants. In a study by Jou and colleagues, nearly 50 previously identified human KCNH2 variants were examined for their ability to restore cardiac repolarization in kcnh2-knockdown zebrafish embryos.38 This model was able to accurately predict whether variants were benign or pathogenic with a high predictive value. Becker and colleagues have also demonstrated the value of zebrafish for modeling TNNT2 mutations associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.39

Human cell models

A major technological advance for establishing cell models of human diseases involves reprogramming somatic cells such as skin fibroblasts or leukocytes to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC).40,41 This technology can enable the derivation of differentiated cell types such as cardiac myocytes from genetically-defined subjects. Several reports have demonstrated the utility of this approach to model various inherited cardiovascular disorders including monogenic arrhythmia susceptibilities (e.g., congenital long-QT syndrome),42,43 familial cardiomyopathies,44-46 and more complex phenotypes (e.g., LEOPARD syndrome).47 Use of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from patients with defined genetic conditions offers an advanced cellular platform to demonstrate the pathogenicity of specific variants. These cells can also be targeted by means of various genome editing methods to introduce a putative disease-causing variant.48,49 Comparison of functional and cellular properties of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from the original cell line and its isogenic mutant derivative provides a strategy to validate that genetic causality stems from a particular variant and not another unrecognized genetic change. A comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of various approaches for functionally annotating variants is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of some experimental models for functional annotation of genetic variants.

| Model system | Advantages | Disadvantages | Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|

| in vitro | |||

| heterologous cells | Rapid; inexpensive | Noncardiac cells | Good for molecular phenotyping |

| human iPSC-CM1 | Human origin; cardiac cell | Slow; expensive; requires specialized expertise |

Immaturity and heterogeneity of cells are confounding factors |

| in vivo | |||

| mice | Mammalian; detailed phenotyping |

Slow; expensive; not human; not scalable |

Not ideal for genes with different expression in human vs mice |

| zebrafish | More rapid and less expensive than mice; scalable |

Two-chamber heart; not human | expensive infrastructure and specialized expertise required |

iPSC = induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes

Summary

Establishing causality of putative disease-causing variants in monogenic and genetically complex traits is an important and evolving concept in modern medicine. Evidence of co-segregation of phenotype with a variant within a family affected by a monogenic disorder should be vigorously sought, although should be cautiously interpreted in very large families where phenocopies may be present. For situations where this is not feasible, a variety of predictive and experimental approaches are available to assess the likelihood of pathogenicity. However, no single strategy will succeed in all cases. Some disorders such as channelopathies may be highly amenable to specific experimental approaches (e.g., electrophysiology) to assign molecular phenotypes whereas other disorders may require analyses in animal models. Emerging strategies to establish pluripotent cells from genetically defined subjects or to engineer specific mutations in reference human stem cells offer new approaches to building better disease models with which to prove genetic causality. Determining genetic causality in the clinical setting should be a collaborative effort between geneticists, genetic testing laboratory professionals, clinicians and, where appropriate, researchers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by NIH grants HL122010 (A.L.G.) and HL061322 and U54052646 (E.M.M.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial disclosures related to this work

REFERENCES

- 1.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Emond MJ, Nickerson DA, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shendure J, Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingles J, Sarina T, Yeates L, Hunt L, Macciocca I, McCormack L, et al. Clinical predictors of genetic testing outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genet Med. 2013;15:972–977. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingsmore SF, Lindquist IE, Mudge J, Gessler DD, Beavis WD. Genome-wide association studies: progress and potential for drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:221–230. doi: 10.1038/nrd2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton N, Li D, Rampersaud E, Morales A, Martin ER, Zuchner S, et al. Exome sequencing and genome-wide linkage analysis in 17 families illustrate the complex contribution of TTN truncating variants to dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:144–153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, Ioannidis JP, et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupski JR, Belmont JW, Boerwinkle E, Gibbs RA. Clan genomics and the complex architecture of human disease. Cell. 2011;147:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards CS, Bale S, Bellissimo DB, Das S, Grody WW, Hegde MR, et al. ACMG recommendations for standards for interpretation and reporting of sequence variations: Revisions 2007. Genet Med. 2008;10:294–300. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b5cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couzin-Frankel J. Return of unexpected DNA results urged. Science. 2013;339:1507–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.339.6127.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACMG Updates Recommendation on "Opt Out" for Genome Sequencing Return of Results. 2014 https://www.acmg.net/docs/Release_ACMGUpdatesRecommendations_final.pdf.

- 12.Marth GT, Yu F, Indap AR, Garimella K, Gravel S, Leong WF, et al. The functional spectrum of low-frequency coding variation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R84. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-9-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronson SJ, Clark EH, Varugheese M, Baxter S, Babb LJ, Rehm HL. Communicating new knowledge on previously reported genetic variants. Genet Med. 2012;14:713–719. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golbus JR, Puckelwartz MJ, Fahrenbach JP, lefave-Castillo LM, Wolfgeher D, McNally EM. Population-based variation in cardiomyopathy genes. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:391–399. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.962928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan S, Caleshu CA, Dunn KE, Foti MJ, Moran MK, Soyinka O, et al. Cardiac structural and sarcomere genes associated with cardiomyopathy exhibit marked intolerance of genetic variation. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:602–610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.963421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Refsgaard L, Holst AG, Sadjadieh G, Haunso S, Nielsen JB, Olesen MS. High prevalence of genetic variants previously associated with LQT syndrome in new exome data. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:905–908. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risgaard B, Jabbari R, Refsgaard L, Holst A, Haunso S, Sadjadieh A, et al. High prevalence of genetic variants previously associated with Brugada syndrome in new exome data. Clin Genet. 2013;84:489–495. doi: 10.1111/cge.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O'Connor TD, Fu W, Kenny EE, Gravel S, et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012;337:64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1219240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabor HK, Auer PL, Jamal SM, Chong JX, Yu JH, Gordon AS, et al. Pathogenic variants for Mendelian and complex traits in exomes of 6,517 European and African Americans: implications for the return of incidental results. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorschner MO, Amendola LM, Turner EH, Robertson PD, Shirts BH, Gallego CJ, et al. Actionable, pathogenic incidental findings in 1,000 participants' exomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacArthur DG, Tyler-Smith C. Loss-of-function variants in the genomes of healthy humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R125–R130. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacArthur DG, Balasubramanian S, Frankish A, Huang N, Morris J, Walter K, et al. A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science. 2012;335:823–828. doi: 10.1126/science.1215040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim ET, Wurtz P, Havulinna AS, Palta P, Tukiainen T, Rehnstrom K, et al. Distribution and medical impact of loss-of-function variants in the Finnish founder population. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyegaard M, Overgaard MT, Sondergaard MT, Vranas M, Behr ER, Hildebrandt LL, et al. Mutations in calmodulin cause ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crotti L, Johnson CN, Graf E, De Ferrari GM, Cuneo BF, Ovadia M, et al. Calmodulin mutations associated with recurrent cardiac arrest in infants. Circulation. 2013;127:1009–1017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Accounting for human polymorphisms predicted to affect protein function. Genome Res. 2002;12:436–446. doi: 10.1101/gr.212802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L, Kumar S. Evolutionary Balancing is Critical for Correctly Forecasting Disease Associated Amino Acid Variants. Mol Biol Evol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu H, Huff CD, Moore B, Flygare S, Reese MG, Yandell M. VAAST 2.0: improved variant classification and disease-gene identification using a conservation-controlled amino acid substitution matrix. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:622–634. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bendl J, Stourac J, Salanda O, Pavelka A, Wieben ED, Zendulka J, et al. PredictSNP: robust and accurate consensus classifier for prediction of disease-related mutations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thusberg J, Olatubosun A, Vihinen M. Performance of mutation pathogenicity prediction methods on missense variants. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:358–368. doi: 10.1002/humu.21445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan DM, Kiezun A, Baxter SM, Agarwala V, Green RC, Murray MF, et al. Development and validation of a computational method for assessment of missense variants in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galehdari H, Saki N, Mohammadi-Asl J, Rahim F. Meta-analysis diagnostic accuracy of SNP-based pathogenicity detection tools: a case of UTG1A1 gene mutations. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2013;4:77–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, Rehm HL, Shendure J, Abecasis GR, et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014;508:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson CL, Kuzmicki CE, Childs RR, Hintz CJ, Delisle BP, January CT. Large-scale mutational analysis of Kv11.1 reveals molecular insights into type 2 long QT syndrome. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.den Hoed M, Eijgelsheim M, Esko T, Brundel BJ, Peal DS, Evans DM, et al. Identification of heart rate-associated loci and their effects on cardiac conduction and rhythm disorders. Nat Genet. 2013;45:621–631. doi: 10.1038/ng.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jou CJ, Barnett SM, Bian JT, Weng HC, Sheng X, Tristani-Firouzi M. An In Vivo Cardiac Assay to Determine the Functional Consequences of Putative Long QT Syndrome Mutations. Circ Res. 2013;112:826–830. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker JR, Deo RC, Werdich AA, Panakova D, Coy S, MacRae CA. Human cardiomyopathy mutations induce myocyte hyperplasia and activate hypertrophic pathways during cardiogenesis in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:400–410. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, Jung CB, Lam JT, Bott-Flugel L, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Caspi O, Winterstern A, et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caspi O, Huber I, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Maizels L, Boulos M, et al. Modeling of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:557–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, Han L, Sanchez-Freire V, Abilez OJ, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:130ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han L, Li Y, Tchao J, Kaplan AD, Lin B, Li Y, et al. Study familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104:258–269. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'Souza SL, Ang YS, Schaniel C, Lee DF, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellin M, Casini S, Davis RP, D'Aniello C, Haas J, Ward-van OD, et al. Isogenic human pluripotent stem cell pairs reveal the role of a KCNH2 mutation in long-QT syndrome. EMBO J. 2013;32:3161–3175. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Liang P, Lan F, Wu H, Lisowski L, Gu M, et al. Genome editing of isogenic human induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulates long QT phenotype for drug testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]