Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conditions involving excessive eating (e.g. obesity, binge / loss of control eating) are increasingly prevalent within pediatric populations, and correlational and some longitudinal studies have suggested inter-relationships between these disorders. In addition, a number of common neural correlates are emerging across conditions, e.g. functional abnormalities within circuits subserving reward processing and executive functioning. To explore this potential cross-condition overlap in neurobehavioral underpinnings, we selectively review relevant functional neuroimaging literature, specifically focusing on studies probing i) reward processing, ii) response inhibition, and iii) emotional processing and regulation, and outline three specific shared neurobehavioral circuits. Based on our review, we also identify gaps within the literature that would benefit from further research.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbidity, fMRI, obesity, overweight

Introduction

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obesity – a condition involving eating beyond metabolic needs – are significant problems in pediatric populations1,2,3,4,5 ADHD is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses of childhood, affecting approximately 8–10% of US school age children, while worldwide estimates are slightly lower at approximately 5%.1,2,6 Additionally, more than 40 million children under the age of five worldwide5, and one third of children and adolescents in the US are currently considered overweight or obese.3,4 There is also evidence for substantial prevalence of Loss of Control eating (LOC) in children; this phenotype is a counterpart to the diagnosis of Binge Eating Disorder in adults in that it features episodes of perceived loss of control over eating2, but due to the complexity of calculating metabolic needs in children, the amount consumed in a binge episode is not required to be ‘objectively’ large.7 Prevalence of LOC in children aged 6–14 years old ranges from 2–10% in studies conducted in various countries including the US, Germany and Israel, with studies of overweight children reporting a 15–37% prevalence.8

ADHD and obesity

Within the ADHD literature, studies of both clinical and community samples have suggested an association between ADHD diagnosis and/or symptoms and overweight/obesity throughout development. For example, Holtkamp and colleagues (2004) found that 19.6% of ADHD boys in sample of inpatients and outpatients referred to psychiatry met criteria for overweight and 7.2% for obesity.9 A recent study comparing rates of obesity and overweight in boys diagnosed with ADHD to those in typically developing (TD) boys found that the ADHD group had higher rates of overweight.10 Further, in a large population-based study of adolescent health, Fuemmeler et al found that, compared with those reporting no symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity, participants with greater than 3 symptoms had higher BMIs in adolescence. Moreover, those with over 3 symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity in adolescence had the highest risk for obesity in adulthood.11 Using a longitudinal design, a prospective follow-up study of 6–12-year-old boys with and without ADHD showed that at 33-year follow-up (average age = 42 years-old) men diagnosed with ADHD in childhood had significantly higher BMIs and obesity rates than those without childhood ADHD.12

Perhaps more research has taken the reverse approach of examining the presence of ADHD diagnosis and traits in children who are overweight or obese. In a study of obese children, almost 58% of participants met criteria for comorbid ADHD.13 Increased rates of diagnosed ADHD have also been found in obese compared with TD adolescents (i.e., 13% vs. 3.3%).14 Additionally, studies have demonstrated greater ADHD symptomatology (i.e., inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity) in overweight/obese children, with one large prospective study of 8,106 children (7–8 years-old at baseline) finding that childhood ADHD symptoms significantly predicted adolescent obesity at age 16.15 In contrast, childhood obesity did not predict ADHD symptoms in adolescence, suggesting that ADHD symptomatology may predispose to overweight/obesity rather than the other way round.15

ADHD and binge / loss of control eating

Although ADHD has been associated with binge eating disorder in adults,16,17 relatively little is known about the relationship between ADHD and binge / loss of control eating in children. However, one study of adolescents, aged 12–20 years old, found that those with either ADHD or ADD were more likely to binge compared to controls.18 Additionally, in a retrospective chart review of patients from two community child and adolescent psychiatry clinics (mean age 10.8 (3.7 SD)) there was a significant association between ADHD and binge eating as assessed by the Children’s Binge Eating Disorder Scale.19 ADHD symptoms have been suggested to contribute to eating pathology,16,19 and particularly impulsivity symptoms, in adolescents,20 and impulsivity is a characteristic feature of both ADHD21 and LOC22 eating in children – this marked phenotypic overlap suggests that further research to explore potential comorbidity is warranted.

Why do we observe these associations between ADHD, obesity and binge/loss of control eating phenotypes? Since all conditions are either behaviorally defined (ADHD, binge/loss of control eating) or are the result of long-term engagement in a particular pattern of behavior (obesity), the brain is likely to play an important role23, and given the type of deficits displayed in each condition, abnormalities within circuits subserving reward processing,24,25 and circuits executive functioning, e.g. response inhibition,26–30 seem likely candidates. Here, we draw on functional neuroimaging literatures for pediatric ADHD, obesity and binge / loss of control eating to review evidence for overlapping neurobiological correlates. In line with previous theories regarding the relationship between ADHD and obesity (16,31), we include functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies probing reward processing and executive function, specifically response inhibition. However, since affective symptoms are a core part of the binge / loss of control eating phenotype, as well as an associated feature of ADHD, we also include relevant studies probing emotional processing and regulation.

Since this is a brief, conceptually-driven review, we focus on presenting the most informative key studies rather than comprehensively describing all potentially relevant studies and findings. However, where pediatric fMRI studies are limited (e.g. for binge / loss of control eating), we refer to related adult studies, neuropsychological studies, and studies using alternative neuroimaging modalities, on the basis that there are likely to be significant similarities in the identified neurobehavioral circuits. In order to make our search strategy as transparent as possible, we report here the terms used to source studies for our core topic areas: [obesity or binge or loss of control] and [children or adolescents] and [fMRI] and [food or reward or inhibition or disinhibition or impulsivity or [eating and emotion]; [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or ADHD] and [children or adolescents] and [fMRI] and [emotion or emotion regulation or response inhibition or reward processing].

Reward Processing

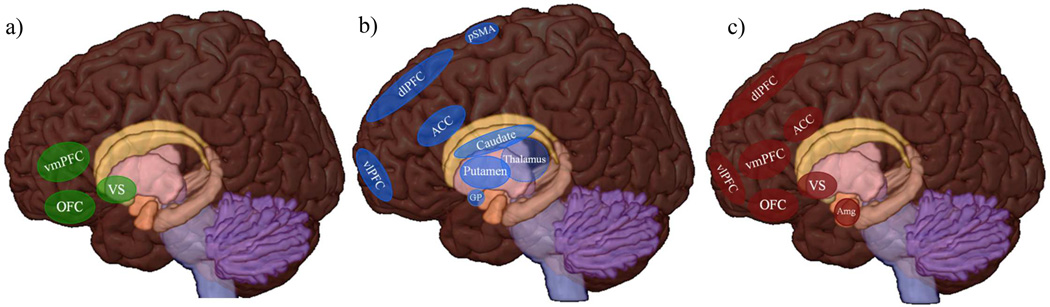

In humans, reward processing is subserved by a cortico-basal ganglia network including (but not confined to) the midbrain, ventral striatum (VS) (particularly nucleus accumbens [NAcc]), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and other areas of the prefrontal cortex (PFC).32–34 (see Figure 1a) fMRI paradigms probing reward circuitry often examine anticipation of reward, receipt of reward, and impact of reward delay (i.e., immediate vs. delayed reward).

Figure 1.

Neural Circuitry Involved in Reward Processing (a), Response Inhibition (b) and Emotional Processing and Regulation (c)

Note. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex, Amg = amygdala, dlPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, GP= globus pallidus, OFC= orbitofrontal cortex, pSMA= pre-supplementary motor area, vlPFC= ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, vmPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex, VS = ventral striatum.

ADHD

The behavioral and neuropsychological heterogeneity seen in children with ADHD has led to theoretical models positing multiple developmental pathways to the disorder, involving impairments in cognition, motivation and self-regulation.35,36 The dual-pathway model proposed by Sonuga-Barke36, for example, suggests two distinct “pathways” or subtypes of the disorder. Via one pathway, ADHD symptoms arise from abnormalities within cortico-striatal circuits, resulting in poor inhibitory control; via the other, symptoms are correlated with abnormalities within reward circuitry, particularly the NAcc, manifesting in altered reward processing and anticipation.

Consistent with the model outlined above, a number of functional neuroimaging studies suggest abnormalities in motivational and reward processing circuitry in children with ADHD compared to TD children. For example, studies of reward processing have consistently revealed differential VS activation in ADHD compared to TD youth. Specifically, using a Monetary Incentive Delay task (MID), in which a participant responds to stimuli after being cued about whether the trial is a “gain” trial (i.e., opportunity to win money) or a “loss-avoidance” trial (i.e., opportunity to avoid losing money), Scheres and colleagues found a relative hypo-activation in the VS in anticipation of gain (but not loss) trials among ADHD (vs. TD) adolescents which was associated with higher levels of hyperactivity/impulsivity, but not inattention. Group differences in VS activity were not shown when comparing trials of increasing monetary rewards, indicating that VS hypo-activation in ADHD may be specific to reward anticipation.37 VS hypo-activation during reward anticipation has also been shown in adults with ADHD, for both immediate and delayed rewards.38,39 In contrast, using a different task, Paloyelis et al. found that adolescent boys with ADHD-combined type (vs. TD adolescent boys) showed increased VS activity to reward receipt (i.e., a successful outcome), but no group differences during reward anticipation.34 These contrasting findings could reflect study differences in sample characteristics (e.g. gender) or tasks used (i.e. MID vs. novel paradigm).

Reward tasks have also revealed other regional functional differences. Specifically, using a reward-based continuous performance task, in which subjects are presented with a stream of letters and required to respond to a target letter to obtain monetary rewards, Rubia and colleagues found that compared to TD children, those with ADHD showed hyper-responsivity in the left ventrolateral OFC and bilateral superior temporal lobe during reward receipt which was attenuated with stimulant medication, supporting theories of increased to reward sensitivity in ADHD as well as a “normalizing effect” of medication.40,41 A recent resting-state functional connectivity (rs-fcRI) study additionally found that compared to TD children, children with ADHD had atypical functional connections between NAcc and cortical regions (i.e., increased connectivity between NAcc, left anterior PFC and ventromedial PFC [vmPFC]) which were related to greater impulsivity during a delayed discounting task.42 Together these results suggest that abnormal responses to reward anticipation and receipt among children with ADHD may be associated with atypical functional activation and connectivity within reward processing circuitry, particularly the VS/NAcc, and prefrontal regions.

Obesity and binge / loss of control eating

Food, particularly hyperpalatable high fat and high sugar food, constitutes a primary reward, and phenotypes involving excessive eating, such as binge / loss of control eating, are known to involve motivation and reward processing regions within dopaminergic pathways.43–48

A common method of studying food reward processing in the context of adult obesity has been to assess whole-brain activation patterns associated with the presentation of food pictures, i.e. salient and familiar cues previously associated with food reward,49–51 and there have now been several similar studies in children. One study of 10–17 year-olds found that obese vs. lean youth showed greater pre-meal (post 4 h fast) activation in the PFC, greater post-meal activation in the OFC, and relatively smaller post-meal (vs. pre-meal) decreases in NAcc, limbic, and PFC activation in response to food (vs. non-food) pictures.52 A different study of adolescent girls observed that BMI was positively associated with OFC, frontal operculum and putamen responses to appetizing food pictures following a 4–6 h fast.53

However, there is also evidence for impoverished neural responses, rather than greater or more persistent activation, in relation to reward among obese youth. Following a 4 h fast, obese vs. lean children showed lesser activation in the middle frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus in response to food logos vs. blurred baseline images, and lesser activation in a range of frontal, temporal and limbic regions, as well as the insula, in response to food vs. non-food logos.54 In a study comparing responses to food vs. non-food commercials following a 5h fast, obese vs. lean 14–17 year-olds showed lesser activation in the cuneus, cerebellum, vmPFC, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and precuneus, but greater activation in the medial temporal gyrus.55 Finally, compared to lean children, overweight/obese children showed increased dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC) responses, but lesser caudate and hippocampus responses to food pictures; however, prior nutritional state of the participants was not controlled.56 As yet, no neuroimaging studies have examined neural food or reward responses in the context of loss of control eating. However, a recent study of 8–17 year olds with and without LOC, used a visual probe task consisting of pictures of high and low palatable foods and neutral objects to measure sustained attention and found a two-way interaction between BMI-z and LOC eating such that among those with LOC (but not those without LOC), attentional bias towards high palatable foods (vs. neutral) was positively associated with BMI-z.57 On balance the studies described suggest hyperactivation of reward regions and hypoactivation of cognitive control regions among obese children, with contradictory findings (e.g., Davids et al., 2010), potentially explicable by differences pre-scan intake or sample characteristics (e.g. conscious dietary restraint).

Another approach has been to examine neural responses to receipt of liquid food rewards, as well as to conditioned cues signaling the delivery of that reward. An initial study using this design revealed that obese vs. lean adolescent girls showed greater activation in the anterior and middle insula and somatosensory cortex in response to the conditioned cues, but lesser caudate responsivity to receipt itself.58 Using region-of-interest (ROI) analyses of the caudate, putamen and ventral pallidum, the same research group observed that greater increases in striato-pallidal responses to conditioned cues throughout the task (suggesting cue-reward learning), and greater decreases in striato-pallidal responses to food receipt (suggesting habituation) predicted significantly larger 2yr increases in BMI.59 These results suggest that with exposure to food and associated cues, obese people may develop a phenotype of both hyper-responsivity to food cues, and hypo-responsivity to food receipt, which could promote greater initiation of eating followed by overeating to compensate for a blunted consummatory response.

Another stimulating question is to what degree might obese or binge / loss of control individuals also differ in general reward processing? A study of delay discounting (i.e. i.e. the decline in the present value of a reward with delay to its receipt) among obese women found that lesser activation of inferior, middle, and superior frontal gyri on difficult vs. easy trials (i.e. trials where the Now and Later choices had similar subjective values) predicted greater 1–3 y weight gain, suggesting a failure to recruit cognitive control circuitry in relation to delayed reward among those at highest obesity risk.60 In contrast, using an adapted MID paradigm, one study of adolescents found that those with heavier parents showed greater caudate, putamen, insula, thalamus, and OFC responses to receipt, but not anticipation, of monetary reward.61 Further, although we are not aware of any fMRI studies probing reward processing in children with binge / loss of control eating, a MID study comparing obese binge eating adults with obese non-binge eaters observed diminished ventral striatum activation during anticipatory reward and loss at baseline.62 Among those who continued to binge eat post-treatment, results showed diminished recruitment of the ventral striatum and the inferior frontal gyrus during anticipatory reward and reduced activity in the medial prefrontal cortex recruitment during reward outcome.63

Together, these results support the possibility of a general, as well as food-specific dysregulation of reward circuitry in obese and binge / loss of control individuals. However, the pattern of food-specific and general results obtained using MID do not completely agree, suggesting a distinction between neural responsivity to monetary reward (which could reflect innate differences in reward processing), and neural responsivity to food reward (which could reflect learned relationships with food or an innate, specific vulnerability to food reward).

Response Inhibition

Response inhibition refers to the ability to inhibit a ‘prepotent’ response to a stimulus, or the deliberate suppression of actions in order to achieve a goal, and is a key component of executive function. It is typically assessed using behavioral paradigms, including Go/No-Go (GNG) tasks (i.e., responding to one or more stimuli while withholding response to another stimuli) and/or stop signal tasks (i.e., responding to a stimulus until cued by an unpredictable separate signal not to respond). Neural correlates of response inhibition in TD individuals highlight the importance of frontal (premotor, prefrontal) to subcortical (striatal, cerebellar) circuits, in addition to fronto-temporal networks (see Figure 1b).64–66

ADHD

Impaired response inhibition is one of the most common deficits associated with ADHD, with 40–50% of children with ADHD exhibiting response inhibition deficits.67–69 In particular, children with ADHD demonstrate increased intra-subject variability (ISV) of reaction time (RT) compared to TD children during response inhibition tasks.

A robust literature of event-related fMRI studies examines the neural correlates of response inhibition in children with ADHD. Here we focus on studies utilizing GNG and stop-signal tasks, which tap into the same cognitive construct of motor response inhibition.70–72 For example, when required to inhibit a response during GNG tasks (i.e., NoGo trials) children with ADHD have been shown to display less activation within prefrontal regions (e.g., inferior, frontal, superior and medial frontal gyri, ventral PFC)73–75 and striatal-thalamic regions (caudate, globus pallidus and thalamus).73,76 Less consistently, reduced activation in the anterior cingulate gyrus76 and increased activation in the temporal lobes has been observed.75 In children with ADHD, increased ISV during NoGo trials has been associated with increased activation in premotor regions including the rostral supplementary motor area (pre-SMA, important for response preparation and selection), while in TD children increased pre-SMA activation was associated with less ISV.77

Similar results are found in studies using stop-signal paradigms. During successful inhibition trials, children with ADHD compared to TD children demonstrate reduced prefrontal activity (e.g., inferior PFC, VLPFC, DLPFC)78,79 and, during unsuccessful inhibition trials, reduced activity in posterior cingulate, precuneus, ACC and VLPFC.78–80 Further, compared to other forms of psychopathology (e.g., obsessive compulsive disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder), children with ADHD demonstrate less activation in prefrontal regions (DLPFC, VLPFC, inferior prefrontal gyrus).81,82 These deficits appear to persist into adulthood, with Cubillo et al83 finding that, despite equitable behavioral performance on the stop-signal task, adults who were diagnosed with ADHD in childhood demonstrated reduced bilateral fronto-striatial activation compared to TD adults. Moreover, functional connectivity analyses revealed reduced functional inter-regional connectivity during the stop-signal task in fronto-fronto, fronto-stiatial, fronto-cingulate and fronto-parietal networks, suggesting a diffuse pattern of atypical functional connectivity in relation to response control in adults with ADHD.

Hart et al.,84 conducted a recent meta-analysis of the fMRI response control literature in ADHD and concluded that during motor response inhibition tasks, individuals with ADHD (vs. TD) show decreased activation in right inferior frontal cortex (IFC) and insula, right SMA and ACC, right thalamus, left caudate and right occipital lobe. These results compliment a prior meta-analysis which showed that children with ADHD demonstrated hypo-activation during inhibition paradigms in several frontal regions bilaterally and the right superior temporal gyrus, left inferior occipital gyrus, thalamus and midbrain.85 Additionally, use of stimulant medication in children with ADHD has been shown to enhance right IFC/insula activation during response inhibition tasks to normative levels.84 In sum, the literature supports aberrant neural activity in fronto-striatal regions in relation to deficits in response control in individuals with ADHD.

Obesity and binge / loss of control eating

Both obesity and binge / loss of control eating phenotypes may be thought of as resulting in part, or entirely, from a cumulative failure to appropriately inhibit responses, specifically those around food. Some studies investigating the neural correlates of response inhibition in relation to these phenotypes have used food-adapted versions of existing response inhibition tasks, while others have used existing tasks in the groups of interest.

For example, one study required adolescent girls to press a button in response to vegetable pictures (Go trials), but to inhibit in response to dessert pictures (NoGo trials), and found that higher BMI was associated with reduced NoGo activation in a variety of inhibition-associated regions including the superior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC), medial PFC and OFC.86 In contrast, in an adult study using a stop-signal task, obese vs. lean women showed reduced activation in the insula, inferior parietal cortex, cuneus and supplementary motor area (although no behavioral differences in accuracy and response latency) during ‘stop’ as compared to ‘go’ trials.87 Ineffectual inhibition of food intake may also be associated with certain structural characteristics: one large study of 14–21 year-olds found that obese vs. lean participants had lower OFC volume, as well as higher scores on dietary disinhibition – a validated questionnaire measure of how likely one is to be triggered to eat by environmental food cues after a period of restraint.88

As yet, no neuroimaging studies have examined response inhibition deficits in non-purging youth with binge or loss of control eating. However, one study of stop signal behavioral performance, pre- and post- negative mood induction, compared youth with either ADHD symptoms or loss of control eating to TD youth. Results showed that loss of control youth presented with greater increases in negative mood and greater increases in impulsivity (i.e., Go reaction time variability) than ADHD and TD youth suggesting a behavioral interaction between negative affect and response inhibition in loss of control youth, which is likely to have a neural basis.22

Taken together, the results generally suggest that heavier individuals may recruit traditional inhibition-associated frontal neural circuits during both food-related and general inhibition tasks to a lesser degree than lean individuals, and that deficits in response inhibition may increase in relation to negative affect for LOC individuals. However, the lack of significant performance differences in some studies suggests that alternative circuits may also be indicated, and inhibition-related neural circuits in youth with loss of control eating have yet to be explored.

Emotional Processing and Regulation

Emotion regulation has been defined as “an individual’s ability to modify an emotional state so as to promote adaptive, goal-oriented behaviors”, and is essential to interpersonal, academic, and adaptive functioning.89 Affective neuroscience research suggests that effective emotion regulation requires two distinct but interrelated neural systems: (1) circuits involved in the appraisal of emotional stimuli and generation of affective responses (e.g., amygdala, insula, VS, OFC, mPFC) and (2) cognitive control systems involved in regulating these responses (e.g., ACC], dlPFC, medial PFC, vlPFC) (see Figure 1c).90,91

ADHD

Emerging evidence suggests emotional processing and regulation deficits are key impairments in children and adults with ADHD.92 Since the human face is a particularly salient emotional stimulus the majority of work examining emotional processing has focused on responses to emotional faces.93–95 However, while behavioral studies consistently show that children with ADHD (vs. TD) have deficits in identifying emotional faces, in particular those depicting negative emotions, the neural systems underlying this deficit are less clearly elucidated.96 One large study found that children with ADHD showed amygdala hyperactivity when completing subjective fear ratings of neutral faces in comparison to TD, severe mood dysregulation, and bipolar children.97 Similarly, during a subliminal face processing task involving fearful faces, adolescents with ADHD (vs. TD) had greater right amygdala activation as well as greater connectivity detected between the lateral PFC-amygdala – a finding which could represent an amplification of the negative affect associated with fearful faces.98 In contrast, Marsh et al.99 found no amygdala activation differences between ADHD and TD participants while processing fearful face expression, arguing for additional research to clarify the discrepant findings.

A related body of literature has examined the impact of emotional stimuli on attentional control in children with ADHD. Deficits in attentional control particularly vigilance and attentional shifting are hallmarks of ADHD, but less is known about the interaction between attentional control and emotional processing in children with ADHD.67,69 However, using both a standard and an Emotional Stroop task, Posner and colleagues found that on the Emotional Stroop, adolescents with ADHD (vs. TD) showed increased reactivity in the medial PFC, even after controlling for cognitive control differences, suggesting a disturbance in emotional processing over and above cognitive control deficits in children with ADHD.100 Interestingly, this increase activation in the medial PFC was attenuated with stimulant medication to levels approximating those in the TD sample. Compared to bipolar and TD participants, children with ADHD have also shown disorder-specific decreased vlPFC activation for negative compared to neutral words on an Emotional Stroop task, and greater activation in the dlPFC and parietal cortex relative to TD participants.101 Together, these studies suggest that deficits in emotional processing and regulation in children with ADHD are likely to derive from functional abnormalities within fronto-striatial regions.

Obesity and binge / loss of control eating

To our knowledge, there are no reports of behavioral or neuroimaging studies using emotional processing paradigms such as those described above in the context of obesity in either children or adults. However, there have been a couple of imaging studies on stress, which has an emotional component and is associated with increased food intake102 and weight gain103, as well as altered neural responses in several key brain areas.104 For example, in a study eliciting imagination of a personalized stressor, overweight/obese vs. normal-weight adults reported both greater subjective anxiety and greater VS activation – although it should be noted that similar results were also obtained when imagining a relaxing, neutral situation.105 In addition, a recent study of overweight/obese women found increased right amygdala activation in response to milkshake receipt during imagery of stressful, but not neutral scenarios, and that this response was associated with basal cortisol levels. Further, there was a positive relationship between BMI and stress-related OFC response to visual presentation of the milkshake.106

There is a similar dearth of neuroimaging evidence regarding emotional processing in binge / loss of control eating. However both binge eating in adults, and loss of control eating in children have been associated with symptoms including dysfunctional emotional regulation, maladaptive coping strategies107, alexithymia (i.e. difficulty identifying or coping with emotions) as manifested by self-reports of numbing and dissociative symptoms during LOC eating episodes108, and low mood and depressive disorders.109 Additionally there is neurobehavioral evidence to suggest that response inhibition is poorer when children with loss of control eating are faced with a negative affect-inducing task, as noted previously.22 Further, a small number of studies have investigated the neural correlates of emotional eating, i.e. the tendency to eat in response to negative emotion – a behavior similar to binge eating. For example, a positron emission tomography (PET) study of lean adults found that higher emotional eating scores were associated with greater dopamine responses in the dorsal striatum to combined gustatory and olfactory stimulation with a favorite food following an overnight fast.110 More pertinently, a study of adolescent girls assessed fMRI responses to milkshake receipt and anticipated receipt while in a negative or neutral music-induced mood, following a 4–6 h fast. During the negative vs. neutral state, those in the top quartile of emotional eating showed greater parahippocampal gyrus and ACC activation for anticipated receipt, and greater ventral pallidum, thalamus and ACC activation for actual receipt, while those in the lowest quartile showed the reverse pattern.111

To conclude, the research base is currently modest, but together the findings support the possibility that obese individuals and those who report high levels of emotion-related eating may demonstrate differential patterns of neural responsivity to emotion/stress, and also to food consumed during emotional/stressful situations.

Discussion

We have described above the results of a number of studies examining the neural correlates of reward processing, response inhibition and emotional processing/regulation in both pediatric ADHD, and conditions characterized by excessive eating (e.g. obesity, binge / loss of control eating). Although there are gaps in the evidence base (e.g. neuroimaging studies of binge / loss of control eating in children; studies using the same methodologies across different subject groups), there appears to be significant neural overlap in the circuits involved, with all disorders demonstrating functional abnormalities in circuits subserving reward (cortico-basal ganglia network including midbrain, ventral and dorsal striatum, amygdala, OFC and other areas of PFC), response inhibition (frontal (premotor, prefrontal) to subcortical (striatal, cerebellar) circuits, in addition to fronto-temporal networks), and emotional processing (amygdala, insula, VS, OFC) and regulation (e.g., ACC, dlPFC, medial PFC, vlPFC).

Notably though, with regards to reward processing, while aberrant neural activity (vs. TD children) is demonstrated by both ADHD children, obese children and binge / loss of control eating, there appears to be a dissociation within the literature. Specifically, children with ADHD appear to show less neural responsivity to reward anticipation, but greater responsivity to reward receipt, in line with their behavioral preferences for immediate vs. delayed rewards. In contrast, obese/overweight children display the opposite pattern of increased responses to reward anticipation (i.e., food cues) and decreased responses to reward receipt (i.e., food receipt). This phenomenon has important implications for both the neurobiological underpinnings, and the appropriate treatment approaches, for each condition.

In terms of response inhibition, evidence suggests that both ADHD and obese/overweight individuals have decreased PFC activity during response inhibition tasks; however, for ADHD individuals fronto-striatal and basal ganglia regions are also implicated, whereas in obese/overweight individuals the literature suggests involvement of parietal and occipital (i.e., cuneus) regions - consistent with the differing clinical presentations of these two groups. In loss of control adolescents there also appears to be an impact of negative mood on response inhibition that may contribute to impulsive responding in relation to food choices.

Finally, with regard to emotional processing and regulation, the literature suggests that for children with ADHD abnormalities in fronto-striatial responsivity and possibly amygdala activity underlie observed deficits. There is a paucity of research examining emotional processing and regulation in obese/overweight children and those with binge / loss of control eating, although existing work points towards a potential interaction between negative emotional states and response to reward as well as increased impulsivity (i.e., deficits in response inhibition).

Although the studies of neural correlates that we have described are informative, it is important to acknowledge that they do not constitute studies of neural mechanisms, per se. Such studies can, however, be informative about mechanisms, both by a) confirming and extending mechanistic work in animals or model systems to human disorders, and b) highlighting areas of differential functioning in which more mechanistic hypotheses can be tested. An example of the former is that physiological work, particularly with primates has implicated the importance of the amygdala in mediating many aspects of emotional responding (e.g., encoding motivational significance or value of a stimuli, etc)112,113 resulting in the exploration of the role of the limbic system in human psychiatric disorders, including ADHD, which are often characterized by deficits in emotional processing or regulation. An example of the latter might be using data on neural correlates to highlight an inhibitory region or circuit that shows hypofunction in the condition of interest, then testing whether a targeted intervention strategy is able to boost activation in that circuit (e.g. Yokum & Stice, IJO 2013114), and ultimately whether the degree to which activity is boosted is predictive of success.

A number of broad questions, then, remain, each with associated research directions. First, to what extent does the circuitry that overlaps between conditions reflect overlapping symptoms? To address this, comorbidity studies that examine each disorder both in isolation and in combination with the other disorder of interest will be required. Second, how clinically meaningful are these observed neural similarities? Several studies demonstrate a disconnect between neural and behavioral abnormalities, raising the question of whether neural plasticity may allow non-conventional brain areas to perform the experimental tasks administered just as well as those used by typically-developing children. To explore this further, longitudinal studies beginning early in life will be required. Third, how might the neurobehavioral domains we have specified interact with each other? There is already some stimulating evidence for deficits in response inhibition being potentiated by difficulties with emotional regulation, and the complexity of the brain makes it extremely likely that the circuits we have described are in communication, possibly leading to additive and interactive effects on symptomatology. Functional connectivity approaches may help to shed light on this question, particularly those examining co-activation between circuits as well as individual brain regions. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, how does atypical neural activity in each disorder relate to prognosis and treatment outcomes, in particular efficacy? In the case of ADHD, it appears that in some domains (i.e., response inhibition) stimulant medication use can “normalize” neural activation patterns, but studies of how treatment affects neural activation in children with conditions characterized by excessive eating are needed, and studies of neurobehaviorally-informed interventions that specifically target dysfunctional circuits will be a long-term goal for all of the conditions discussed. Pursuing all of the avenues described above should help not only to reveal intervention-relevant information regarding ADHD, obesity and binge eating, but to shed light on more fundamental behavior-brain relationships.

Acknowledgments

Karen Seymour has the following disclosure: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Employee, Start-up funding

Susan Carnell has the following disclosure: NIDDK, NIH grant, Research support

Shauna Reinblatt has the following disclosure: NIH, Researcher, NIMH grant K23 MH 083000 Osler Institute, Past lecturer, Continuing Medical Education Board Review Course

Footnotes

Disclosure information:

Leora Benson has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Getahun D, Jacobsen SJ, Fassett MJ, Chen W, Demissie K, Rhoads GG. Recent trends in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(3):282–288. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostics and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obesity and overweight: Fact sheet no 311. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2011;120(1):108–118. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Marcus MD, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Loss of control eating disorder in children age 12 years and younger: proposed research criteria. Eat Behav. 2008;9(3):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtkamp K, Konrad K, Muller B, et al. Overweight and obesity in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2004;28(5):685–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanc T, Slopien A, Wolanczyk T, et al. ADHD and overweight in boys: cross-sectional study with birth weight as a controlled factor. European child & adolescent psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0531-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuemmeler BF, Ostbye T, Yang C, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. Association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and obesity and hypertension in early adulthood: a population-based study. International journal of obesity. 2011;35(6):852–862. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortese S, Ramos Olazagasti MA, Klein RG, Castellanos FX, Proal E, Mannuzza S. Obesity in men with childhood ADHD: a 33-year controlled, prospective, follow-up study. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1731–e1738. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agranat-Meged AN, Deitcher C, Goldzweig G, Leibenson L, Stein M, Galili-Weisstub E. Childhood obesity and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a newly described comorbidity in obese hospitalized children. The International journal of eating disorders. 2005;37(4):357–359. doi: 10.1002/eat.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erermis S, Cetin N, Tamar M, Bukusoglu N, Akdeniz F, Goksen D. Is obesity a risk factor for psychopathology among adolescents? Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2004;46(3):296–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalife N, Kantomaa M, Glover V, et al. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are risk factors for obesity and physical inactivity in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortese S, Angriman M, Maffeis C, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2008;48(6):524–537. doi: 10.1080/10408390701540124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattos P, Saboya E, Ayrao V, Segenreich D, Duchesne M, Coutinho G. Comorbid eating disorders in a Brazilian attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder adult clinical sample. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2004;26(4):248–250. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462004000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Resnick MD, Garwick A, Blum RW. Body dissatisfaction and unhealthy weight-control practices among adolescents with and without chronic illness: a population-based study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1995;149(12):1330–1335. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170250036005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinblatt SP, Leoutsakos JM, Mahone EM, Forrester S, Wilcox HC, Riddle MA. Association between binge eating and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in two pediatric community mental health clinics. The International journal of eating disorders. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eat.22342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP, Patterson KA, Lee JC. Eating pathology among adolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(1):225–235. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alderson RM, Rapport MD, Kofler MJ. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and behavioral inhibition: a meta-analytic review of the stop-signal paradigm. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35(5):745–758. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann AS, Rief W, Hilbert A. Impulsivity and negative mood in adolescents with loss of control eating and ADHD symptoms: an experimental study. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s40519-013-0004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortese S, Morcillo Penalver C. Comorbidity between ADHD and obesity: exploring shared mechanisms and clinical implications. Postgraduate medicine. 2010;122(5):88–96. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu LL, Li BM, Yang J, Wang YW. Does dopaminergic reward system contribute to explaining comorbidity obesity and ADHD? Medical hypotheses. 2008;70(6):1118–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell BC, Eisenberg D. Obesity, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and the dopaminergic reward system. Collegium antropologicum. 2007;31(1):33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graziano PA, Bagner DM, Waxmonsky JG, Reid A, McNamara JP, Geffken GR. Co-occurring weight problems among children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the role of executive functioning. International journal of obesity. 2012;36(4):567–572. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauli-Pott U, Albayrak O, Hebebrand J, Pott W. Association between inhibitory control capacity and body weight in overweight and obese children and adolescents: dependence on age and inhibitory control component. Child neuropsychology : a journal on normal and abnormal development in childhood and adolescence. 2010;16(6):592–603. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2010.485980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortese S, Comencini E, Vincenzi B, Speranza M, Angriman M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and impairment in executive functions: a barrier to weight loss in individuals with obesity? BMC psychiatry. 2013;13:286. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhry Z, Sengupta SM, Grizenko N, et al. Body weight and ADHD: examining the role of self-regulation. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e55351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempsey A, Dyehouse J, Schafer J. The relationship between executive function, AD/HD, overeating, and obesity. Western journal of nursing research. 2011;33(5):609–629. doi: 10.1177/0193945910382533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cortese S, Vincenzi B. Obesity and ADHD: Clinical and Neurobiological Implications. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2012;9:199–218. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knutson B, Cooper JC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reward prediction. Current opinion in neurology. 2005;18(4):411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000173463.24758.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paloyelis Y, Mehta MA, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Kuntsi J. Striatal sensitivity during reward processing in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(7):722.e729–732.e729. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nigg JT, Casey BJ. An integrative theory of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Development and psychopathology. 2005;17(3):785–806. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonuga-Barke EJ. Causal models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: from common simple deficits to multiple developmental pathways. Biological psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheres A, Milham MP, Knutson B, Castellanos FX. Ventral striatal hyporesponsiveness during reward anticipation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61(5):720–724. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strohle A, Stoy M, Wrase J, et al. Reward anticipation and outcomes in adult males with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. NeuroImage. 2008;39(3):966–972. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plichta MM, Scheres A. Ventral-striatal responsiveness during reward anticipation in ADHD and its relation to trait impulsivity in the healthy population: A meta-analytic review of the fMRI literature. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2014;38:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubia K, Halari R, Cubillo A, Mohammad AM, Brammer M, Taylor E. Methylphenidate normalises activation and functional connectivity deficits in attention and motivation networks in medication-naive children with ADHD during a rewarded continuous performance task. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57(7–8):640–652. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luman M, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA. The impact of reinforcement contingencies on AD/HD: a review and theoretical appraisal. Clinical psychology review. 2005;25(2):183–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa Dias TG, Wilson VB, Bathula DR, et al. Reward circuit connectivity relates to delay discounting in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;23(1):33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rada P, Avena NM, Hoebel BG. Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell. Neuroscience. 2005;134(3):737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avena NM, Carrillo CA, Needham L, Leibowitz SF, Hoebel BG. Sugar-dependent rats show enhanced intake of unsweetened ethanol. Alcohol. 2004;34(2–3):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis C, Levitan RD, Muglia P, Bewell C, Kennedy JL. Decision-making deficits and overeating: a risk model for obesity. Obesity research. 2004;12(6):929–935. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis C, Strachan S, Berkson M. Sensitivity to reward: implications for overeating and overweight. Appetite. 2004;42(2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Avena NM, Hoebel BG. A diet promoting sugar dependency causes behavioral cross-sensitization to a low dose of amphetamine. Neuroscience. 2003;122(1):17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corwin RL, Hajnal A. Too much of a good thing: neurobiology of non-homeostatic eating and drug abuse. Physiology & behavior. 2005;86(1–2):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carnell S, Gibson C, Benson L, Ochner CN, Geliebter A. Neuroimaging and obesity: current knowledge and future directions. Obes Rev. 2012;13(1):43–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kennedy J, Dimitropoulos A. Influence of feeding state on neurofunctional differences between individuals who are obese and normal weight: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Appetite. 2014;75:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stice E, Figlewicz DP, Gosnell BA, Levine AS, Pratt WE. The contribution of brain reward circuits to the obesity epidemic. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2013;37(9 Pt A):2047–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruce AS, Holsen LM, Chambers RJ, et al. Obese children show hyperactivation to food pictures in brain networks linked to motivation, reward and cognitive control. International journal of obesity. 2010;34(10):1494–1500. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stice E, Yokum S, Bohon C, Marti N, Smolen A. Reward circuitry responsivity to food predicts future increases in body mass: moderating effects of DRD2 and DRD4. NeuroImage. 2010;50(4):1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruce AS, Lepping RJ, Bruce JM, et al. Brain responses to food logos in obese and healthy weight children. J Pediatr. 2013;162(4):759–764. e752. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Stice E, Harris JL, Brownell KD. Relation of obesity to neural activation in response to food commercials. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(7):932–938. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davids S, Lauffer H, Thoms K, et al. Increased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation in obese children during observation of food stimuli. International journal of obesity. 2010;34(1):94–104. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shank LM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Nelson EE, et al. Attentional bias to food cues in youth with loss of control eating. Appetite. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Veldhuizen MG, Small DM. Relation of reward from food intake and anticipated food intake to obesity: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(4):924–935. doi: 10.1037/a0013600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burger KS, Stice E. Greater striatopallidal adaptive coding during cue-reward learning and food reward habituation predict future weight gain. NeuroImage. 2014;99C:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kishinevsky FI, Cox JE, Murdaugh DL, Stoeckel LE, Cook EW, 3rd, Weller RE. fMRI reactivity on a delay discounting task predicts weight gain in obese women. Appetite. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stice E, Yokum S, Burger KS, Epstein LH, Small DM. Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. J Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4360–4366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6604-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balodis IM, Kober H, Worhunsky PD, et al. Monetary reward processing in obese individuals with and without binge eating disorder. Biological psychiatry. 2013;73(9):877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balodis IM, Grilo CM, Kober H, et al. A pilot study linking reduced fronto-Striatal recruitment during reward processing to persistent bingeing following treatment for binge-eating disorder. The International journal of eating disorders. 2014;47(4):376–384. doi: 10.1002/eat.22204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mostofsky SH, Schafer JG, Abrams MT, et al. fMRI evidence that the neural basis of response inhibition is task-dependent. Brain research. Cognitive brain research. 2003b;17(2):419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubia K, Smith AB, Woolley J, et al. Progressive increase of frontostriatal brain activation from childhood to adulthood during event-related tasks of cognitive control. Human brain mapping. 2006;27(12):973–993. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blasi G, Goldberg TE, Weickert T, et al. Brain regions underlying response inhibition and interference monitoring and suppression. The European journal of neuroscience. 2006;23(6):1658–1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Willcutt E, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biological psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1336–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nigg JT. Neuropsychologic theory and findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the state of the field and salient challenges for the coming decade. Biological psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1424–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Willcutt E, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Nigg JT, Sergeant JA. Recent developments in neuropsychological models of childhood psychiatric disorders. In: Banaschewski T, Rohde LA, editors. Biological child psychiatry: Recent trends and developments. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2008. pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rubia K, Russell T, Overmeyer S, et al. Mapping motor inhibition: conjunctive brain activations across different versions of go/no-go and stop tasks. NeuroImage. 2001;13:250–261. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nigg JT. On inhibition/disinhibition in developmental psychopathology: views from cognitive and personality psychology and a working inhibition taxonomy. Psychological bulletin. 2000;126(2):220–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eagle DM, Bari A, Robbins TW. The neuropsychopharmacology of action inhibition: cross-species translation of the stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199(3):439–456. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Booth JR, Burman DD, Meyer JR, et al. Larger deficits in brain networks for response inhibition than for visual selective attention in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):94–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith AB, Taylor E, Brammer M, Toone B, Rubia K. Task-specific hypoactivation in prefrontal and temporoparietal brain regions during motor inhibition and task switching in medication-naive children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1044–1051. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tamm L, Menon V, Ringel J, Reiss AL. Event-related FMRI evidence of frontotemporal involvement in aberrant response inhibition and task switching in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(11):1430–1440. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000140452.51205.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Durston S, Tottenham NT, Thomas KM, et al. Differential patterns of striatal activation in young children with and without ADHD. Biological psychiatry. 2003;15(10):871–878. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suskauer SJ, Simmonds DJ, Caffo BS, Denckla MB, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH. fMRI of intrasubject variability in ADHD: anomalous premotor activity with prefrontal compensation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(10):1141–1150. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rubia K, Smith AB, Brammer MJ, Toone B, Taylor E. Abnormal brain activation during inhibition and error detection in medication-naive adolescents with ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1067–1075. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rubia K, Overmeyer S, Taylor E, et al. Hypofrontality in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during higher-order motor control: a study with functional MRI. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:891–896. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pliszka SR, Glahn DC, Semrud-Clikeman M, et al. Neuroimaging of inhibitory control areas in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder who were treatment naive or in long-term treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1052–1060. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN. Neural correlates of response inhibition in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry research. 2010;181(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rubia K, Cubillo A, Smith AB, Woolley J, Heyman I, Brammer MJ. Disorder-specific dysfunction in right inferior prefrontal cortex during two inhibition tasks in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder compared to boys with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Human brain mapping. 2010;31(2):287–299. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cubillo A, Halari R, Ecker C, Giampietro V, Taylor E, Rubia K. Reduced activation and inter-regional functional connectivity of fronto-striatal networks in adults with childhood Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and persisting symptoms during tasks of motor inhibition and cognitive switching. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(10):629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA psychiatry. 2013;70(2):185–198. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, et al. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. The American journal of psychiatry. 2012;169(10):1038–1055. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Batterink L, Yokum S, Stice E. Body mass correlates inversely with inhibitory control in response to food among adolescent girls: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2010;52(4):1696–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hendrick OM, Luo X, Zhang S, Li CS. Saliency Processing and Obesity: A Preliminary Imaging Study of the Stop Signal Task. Obesity. 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maayan L, Hoogendoorn C, Sweat V, Convit A. Disinhibited eating in obese adolescents is associated with orbitofrontal volume reductions and executive dysfunction. Obesity. 2011;19(7):1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2–3):25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception I: the neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biological psychiatry. 2003;54(5):504–514. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2005;9(5):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E. Emotion Dysregulation in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leibenluft E, Gobbini MI, Harrison T, Haxby JV. Mothers' neural activation in response to pictures of their children and other children. Biological psychiatry. 2004;56(4):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gobbini MI, Leibenluft E, Santiago N, Haxby JV. Social and emotional attachment in the neural representation of faces. NeuroImage. 2004;22(4):1628–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gobbini MI, Haxby JV. Neural systems for recognition of familiar faces. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(1):32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dickstein DP, Castellanos FX. Face processing in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2012;9:219–237. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, et al. Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(1):61–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Posner J, Nagel BJ, Maia TV, et al. Abnormal amygdalar activation and connectivity in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):828.e823–837.e823. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marsh AA, Finger EC, Mitchell DG, et al. Reduced amygdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behavior disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):712–720. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Posner J, Maia TV, Fair D, Peterson BS, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Nagel BJ. The attenuation of dysfunctional emotional processing with stimulant medication: an fMRI study of adolescents with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2011;193(3):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN. Differential engagement of cognitive and affective neural systems in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2010;16(1):106–117. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, et al. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of "comfort food". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11696–11701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934666100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Block JP, He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Ding L, Ayanian JZ. Psychosocial stress and change in weight among US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):181–192. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dedovic K, D'Aguiar C, Pruessner JC. What stress does to your brain: a review of neuroimaging studies. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(1):6–15. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jastreboff AM, Potenza MN, Lacadie C, Hong KA, Sherwin RS, Sinha R. Body mass index, metabolic factors, and striatal activation during stressful and neutral-relaxing states: an FMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(3):627–637. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rudenga KJ, Sinha R, Small DM. Acute stress potentiates brain response to milkshake as a function of body weight and chronic stress. International journal of obesity. 2013;37(2):309–316. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Czaja J, Rief W, Hilbert A. Emotion regulation and binge eating in children. The International journal of eating disorders. 2009;42(4):356–362. doi: 10.1002/eat.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Goossens L, Eddy KT, et al. A multisite investigation of binge eating behaviors in children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(6):901–913. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. The International journal of eating disorders. 2005;38(2):112–122. doi: 10.1002/eat.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Maynard L, et al. Brain dopamine is associated with eating behaviors in humans. The International journal of eating disorders. 2003;33(2):136–142. doi: 10.1002/eat.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bohon C, Stice E, Spoor S. Female emotional eaters show abnormalities in consummatory and anticipatory food reward: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. The International journal of eating disorders. 2009;42(3):210–221. doi: 10.1002/eat.20615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Phelps EA, LeDoux JE. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron. 2005;48(2):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Paton JJ, Belova MA, Morrison SE, Salzman CD. The primate amygdala represents the positive and negative value of visual stimuli during learning. Nature. 2006;439(7078):865–870. doi: 10.1038/nature04490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yokum S, Stice E. Cognitive regulation of food craving: effects of three cognitive reappraisal strategies on neural response to palatable foods. International journal of obesity. 2013;37(12):1565–1570. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]