Abstract

Objective

Mortality in hospitalized HIV-infected patients is not well described. We sought to characterize in-hospital deaths among HIV-infected patients in the antiretroviral (ART) era and identify factors associated with mortality.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of hospitalized HIV-infected patients who died from 1/1/1995 to 12/31/2011 at an urban teaching hospital. We evaluated trends in early and late ART use and deaths due to AIDS and non-AIDS, and identified clinical and demographic correlates of non-AIDS deaths.

Results

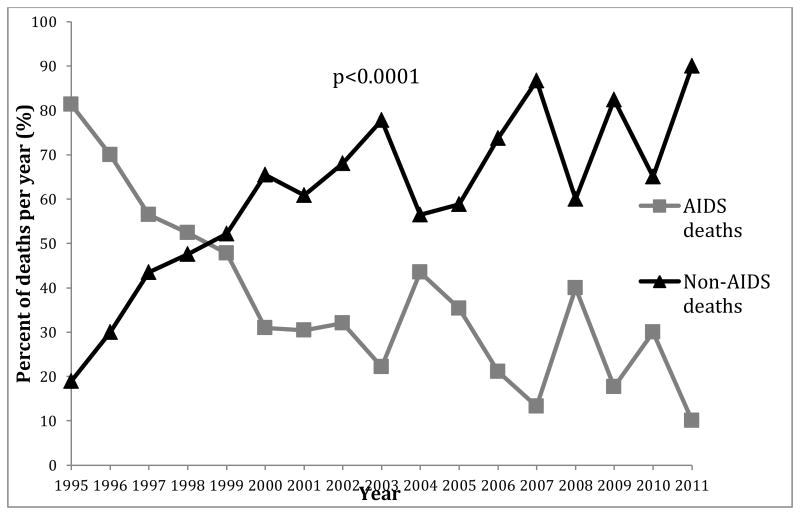

In-hospital deaths declined significantly 1995-2011 (p<0.0001); those attributable to non-AIDS increased (43% to 70.5%, p<0.0001). Non-AIDS deaths were most commonly caused by non-AIDS infection (20.3%), cardiovascular (11.3%) and liver disease (8.5%), and non-AIDS malignancy (7.8%). Patients with non-AIDS compared to AIDS related deaths were older (median age of 48 vs. 40 years, p<0.0001), more likely to be on ART (74.1% vs. 55.8%, p=0.0001), less likely to have a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 (47.2% vs. 97.1%, p<0.0001), and more likely to have a HIV viral load of ≤400 copies/ml (38.1% vs. 4.1%, p<0.0001). Non-AIDS deaths were associated with 4.5 and 4.2 times greater likelihood of comorbid underlying liver and cardiovascular disease, respectively.

Conclusions

Non-AIDS deaths increased significantly during the ART era and are now the most common cause of in-hospital deaths; non-AIDS infection, cardiovascular and liver disease, and malignancies were major contributors to mortality. Higher CD4 cell count, liver and cardiovascular comorbidities were most strongly associated with non-AIDS deaths. Interventions targeting non-AIDS associated conditions are needed to reduce inpatient mortality among HIV-infected patients.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, hospital medicine, epidemiology, health outcomes

Introduction

Successfully treated HIV-infected individuals in the United States currently have life expectancy and mortality rates that are similar to the general population.1-4 A large multinational study found that the excess mortality rate among HIV positive individuals decreased from 40.8 to 6.1 per 1000 person-years from pre-1995 to 2006.1 This is largely due to improved access to comprehensive HIV care, in particular widespread antiretroviral (ART) use. However, the proportion of deaths that are not classically considered AIDS-related such as liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and non-AIDS malignancy has increased,1,5-7 particularly among patients with higher CD4 T-cell counts.5,8 Additionally, despite overall decline in mortality, there is evidence of racial and gender differences, with increased mortality risk associated with female gender and black race.9,10

In the current ART era, HIV care has shifted focus from inpatient to outpatient care with more emphasis on chronic disease management. However, hospitalization rates among HIV-positive persons remain higher than that of the general population. 11,12 A cross-sectional study of HIV-infected persons in the US estimated a hospitalization rate of 26.6 per 100 persons in 2009,13 compared to a rate of 11.9 for the general population during the same year.14 Possible reasons for higher hospitalization rates include complications of aging or other chronic comorbidities, and consequences of behavioral risk factors such tobacco use and substance abuse.

Characterizing deaths among inpatient HIV-infected individuals in the ART era is important to developing targeted interventions to further reduce mortality. Prior studies examining in-hospital deaths of HIV-positive patients evaluated more limited time periods,15-18 and thus did not necessarily assess the full spectrum of changes in mortality that have occurred with the introduction of ART. Furthermore, these studies described causes of death, but did not consistently identify factors associated with non-AIDS deaths. We examined the trends in in-hospital deaths among HIV-infected patients from 1995 to 2011 and identified contributing factors to mortality. As the HIV population is aging, we hypothesized that HIV-infected patients are more likely to die from non-AIDS related death in the late ART era due to factors related to cardiovascular and liver disease, compared to the early ART era.

Methods

The study was performed at Yale-New Haven Hospital, an urban tertiary care academic teaching hospital with 1,008 beds and the state of Connecticut's largest ambulatory HIV clinic. Connecticut ranks 7th nationally (10/100,000) in HIV prevalence; New Haven is second among Connecticut cities in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS.19 We reviewed all patients with an ICD-9 code of HIV or AIDS (ICD9 codes V08 and 042) who died during hospitalization between 1/1/1995 to 12/31/2011. The Yale Human Investigation Committee granted ethical approval to conduct the study.

A standardized data collection tool was used to abstract demographic characteristics (i.e age, gender, and race), medical comorbidities (i.e diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic Hepatitis B or C, liver cirrhosis, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease, alcohol and substance abuse), ART use (yes or no), HIV viral load (VL), CD4 cell count, and causes of death. Comorbidities were defined using the CoDe protocol, a multinational endeavor to standardize data collection in studies of HIV-positive patients.20 Chronic kidney disease included individuals with National Kidney Foundation stage I-V disease. Chronic hepatitis B or C infection was identified in patients who had serologic testing indicative of prior infection. Alcohol and substance abuse were identified when source documents mentioned any history of current alcohol or illicit drug abuse or dependence. ART use was defined as documentation of ART on admission or prescription during hospitalization. This included individuals who were on two or more ART agents. The last HIV VL and CD4 cell count available within one year and closest to death were recorded. HIV VL suppression was defined as < 400 copies/ml.

Two clinicians independently classified the cause of death as AIDS related or non-AIDS related in accordance with published definitions.21,22 Cause of death was determined by review of the medical record, discharge diagnosis, and autopsy report when available. Official death certificates were not available for review. There was discordance in assigning 23 of the 400 causes of death. In these cases, the medical record was reviewed and determined by consensus between the two clinicians.

AIDS related deaths were categorized as non-specified AIDS, AIDS infection, and AIDS malignancy. AIDS related deaths were defined as those caused by conditions meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) AIDS case definition.22 Non-specified AIDS deaths were those occurring in patients with a CD4 count ≤50 cells/mm3 or with an AIDS defining illness, who died from a condition that was not clearly AIDS related. This included septic shock of unclear etiology, first known episode of pneumonia, a gastrointestinal bleed of unclear etiology, and altered mental status of unclear etiology when CSF analysis or imaging of the brain was not available.

Non-AIDS deaths included non-AIDS infection in patients with a CD4 count >50 cells/mm3, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, non-AIDS malignancy, and renal disease (Table 1). Deaths classified as “other” incorporated the deaths that didn't fall into these categories. COPD exacerbation and status asthmaticus were included in this category because there was only one death from each of these causes.

Table 1. Categories of Non-AIDS Death.

| Non-AIDS infection | Infectious etiology not on the list of AIDS-defining conditions, such as Clostridium difficile colitis, endocarditis, bacteremia, non-recurrent bacterial pneumonia or septic shock of unclear cause without a CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mm3 or a documented opportunistic infection |

| Cardiovascular disease | Cardiac arrest without clear cause, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, congestive heart failure (respiratory failure most likely due to pulmonary edema in the setting of known systolic or diastolic heart failure), myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrhythmia |

| Liver disease | Complications of cirrhosis such as variceal bleed, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, and acute liver failure |

| Renal disease | Complications of acute renal failure such as hyperkalemia leading to cardiac arrest. Complications of end stage renal disease such as stopping hemodialysis or calciphylaxis |

| Non-AIDS malignancy | Malignancies not on the AIDS indicator diagnostic list |

| Other causes | Drug overdose, trauma, suicide, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, macrophage activation syndrom, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, status asthmaticus, COPD exacerbation, status epilepticus of unclear cause, complications of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and diabetic ketoacidosis. |

The ‘early’ ART era was defined as 1995 to 2001 and the ‘late’ ART era from 2002 to 2011. During the early period, combination ART was introduced and significantly impacted overall mortality.23,24 The late ART era better reflected current in-hospital deaths, and was compared to the early era to evaluate trends over time.15,25

Chi-square analysis and parametric (t-test and ANOVA) methods compared categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Bivariate analysis was used to determine associations with AIDS vs. non-AIDS deaths in the entire study cohort. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify correlates of non-AIDS deaths in the (a) complete seventeen-year period and (b) late ART era. For all analyses, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Among 12,183 hospital discharges of HIV-infected patients from 1995-2011, 406 (3.3%) died. Six medical records were missing or incomplete; 400 were available for review. The proportion of hospitalized HIV-infected patients who died declined from 6.2% in 1995 to 1.5% in 2011 (p<0.0001).

Table 2 summarizes all 400 patients' demographic and clinical characteristics, and cause of death. The majority were male (65.5%), non-white (73.3%), and taking ART (65.9%), though only one third achieved a VL <400 copies/ml on the most recent measurement available in the year prior to death. The majority (56.3%) died due to non-AIDS related causes.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Analysis of demographics, clinical characteristics, and causes of death of patients in the early (1995-2001) versus the late ART era (2002-2011).

| Total (n=400) | Early era (n=207) | Late era (n=193) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (IQR) | 45 (38-52) | 41 (35-47) | 49 (43-57) | <0.0001 |

| Male gender (%) | 262 (65.5) | 141 (68.1) | 121 (62.7) | 0.25 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| Black | 238 (59.5) | 124 (59.9) | 114 (59.1) | 0.87 |

| White | 105 (26.3) | 55 (26.6) | 50 (25.9) | 0.88 |

| Hispanic | 55 (13.8) | 27 (13.0) | 28 (14.5) | 0.67 |

| Median CD4 cells/mm3* (IQR) | 90 (12-248) | 50 (10-150) | 153 (22-399) | <0.0001 |

| HIV VL≤400 copies/ml** (%) | 77 (31.3) | 12 (13.3) | 65 (41.7) | <0.0001 |

| On ART (%) | 257 (65.9) | 120 (58.3) | 137 (74.5) | 0.0008 |

| Cause of Death (%) | ||||

| AIDS-related (%) | 175 (43.8) | 118 (57.0) | 57 (29.5) | <0.0001 |

| AIDS infection | 85 (21.3) | 58 (28.0) | 27 (14.0) | 0.82 |

| Non-specified AIDS | 73 (18.3) | 46 (22.2) | 27 (14.0) | 0.99 |

| AIDS malignancy | 17 (4.3) | 14 (6.8) | 3 (1.6) | 0.17 |

| Non-AIDS related (%) | 225 (56.3) | 89 (43.0) | 136 (70.5) | <0.0001 |

| Non-AIDS infection | 81 (20.3) | 32 (15.5) | 49 (25.4) | 0.99 |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (11.3) | 16 (7.7) | 29 (15.0) | 0.54 |

| Liver-related | 34 (8.5) | 18 (8.7) | 16 (8.3) | 0.08 |

| Malignancy | 31 (7.8) | 6 (2.9) | 25 (13.0) | 0.01 |

| Renal failure | 18 (4.5) | 8 (3.9) | 10 (5.2) | 0.66 |

| Other | 16 (4.1) | 9 (4.5) | 7 (3.6) | 0.16 |

Last CD4 count > 200 cells/mm3 in the year prior to death

VL <400 copies/ml in the year prior to death

Among all AIDS related deaths 1995-2011 (Table 2), AIDS defining infection was the most common cause (21.3%), followed by non-specified AIDS (18.3%), and AIDS malignancy (4.3%). The proportion of non-AIDS related deaths increased significantly over time (Figure 1). The most common cause of non-AIDS related deaths was non-AIDS infection (20.3%), followed by cardiovascular disease (11.35), liver disease (8.5%), malignancy (7.8%), and renal failure (4.5%). The most common non-AIDS infection was sepsis in 43 patients (60.6%), followed by non-recurrent bacterial pneumonia in 24 patients (33.8%), and Clostridium difficile infection in 4 patients (5.6%). Non-AIDS related malignancy was the only category to significantly increase from the early ART to late ART era (p=0.01).

Figure 1. Trends in AIDS related versus non-AIDS related deaths (1995-2011).

Compared to those dying of AIDS related causes over the 17-year period (Table 3), patients dying of non-AIDS related causes were older, less likely to have a CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/mm3 (p<0.0001), and more likely to be on ART and virologically suppressed (p<0.0001). Patients who died from non-AIDS related causes were also more likely to have diabetes mellitus (p=0.01), CKD (p<0.0001), hepatitis C (p<0.0001), liver cirrhosis (p<0.0001), hypertension (p=0.0002), CAD (p=0.004), and COPD (p=0.04). Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in gender, race, or substance abuse between AIDS related and non-AIDS related deaths.

Table 3.

Unadjusted analysis of demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with AIDS versus non-AIDS deaths 1995-2011 (n=400).

| AIDS (n=175) | Non-AIDS (n=225) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (IQR) | 40 (35-48) | 48 (42-55) | <0.0001 |

| Male gender | 115 (43.9) | 147 (56.1) | 0.94 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Black | 105 (60.3) | 133 (59.4) | 0.84 |

| White | 41 (23.6) | 64 (28.6) | 0.26 |

| Hispanic | 28 (16.1) | 27 (12.1) | 0.25 |

| On ART | 97 (55.8) | 160 (74.1) | 0.0001 |

| CD4<200 cells/mm3* (%) | 167 (97.1) | 95 (47.2) | <0.0001 |

| HIV VL≤400 copies/ml** (%) | 2 (4.1) | 75 (38.1) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 13 (7.4) | 35 (15.6) | 0.01 |

| Renal disease | |||

| CKD | 21 (12) | 73 (32.4) | <0.0001 |

| On dialysis | 9 (5.1) | 47 (20.9) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | |||

| Hepatitis C | 38 (21.7) | 130 (57.8) | <0.0001 |

| Cirrhosis | 14 (8) | 67 (29.8) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | |||

| Hypertension | 18 (10.3) | 56 (24.9) | 0.0002 |

| CAD | 2 (1.1) | 16 (7.1) | 0.004 |

| CHF | 13 (7.4) | 29 (12.9) | 0.08 |

| COPD | 5 (2.9) | 17 (7.6) | 0.04 |

| Alcohol abuse | 9 (5.1) | 18 (8.0) | 0.26 |

| Polysubstance abuse | 10 (5.7) | 22 (9.8) | 0.14 |

CKD: Chronic kidney disease

CAD: Coronary Artery Disease

CHF: Congestive Heart Failure

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Last CD4 count > 200 cells/mm3 in the year prior to death

VL <400 copies/ml in the year prior to death

Associations with Non-AIDS Deaths

Among all clinical factors associated with non-AIDS deaths (Table 4), only last CD4 within the year prior to death > 200 cells/mm3, VL ≤400 copies/ml in the year prior to death, and liver and cardiovascular comorbidities were independently associated with non-AIDS deaths. The last CD4 count > 200 cells/mm3 in the year prior to death was the strongest correlate (OR =16.5; 5.3, 51.4) of non-AIDS deaths while gender and race were not significant.

Table 4.

Clinical factors and comorbidities associated with non-AIDS deaths by ART Era.

| Overall (1995-2011) | Early Era (1995-2001) | Late Era (2002-2011) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 400 | 207 | 193 | |||

| Non-AIDS | 225 | 89 | 136 | |||

| AIDS | 175 | 118 | 57 | |||

| Odds Ratio1 (95%CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio2 (95% CI) | Odds Ratio1 (95%CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio2 (95% CI) | Odds Ratio1 (95%CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio2 (95% CI) | |

| Clinical Factors | ||||||

| Age (per year) | 1.06 (1.04,1.08) | * | 1.03 (1.01,1.06) | * | 1.07 (1.03,1.1) | * |

| Male Gender | 0.98 (0.6,1.5) | * | 1.04 (0.6,1.9) | * | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | * |

| White Race (vs Non-white) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | * | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | * | 0.4 (0.2,0.8) | * |

| CD4 >200 cells/mm3 ## | 37.6 (14.8,95.5) | 16.5 (5.3,51.4) | 24.4 (7.1,83.2) | 17.4 (3.4,88.3) | 45.4 (10.5,195.5) | 25.9 (5.0,134.5) |

| HIV VL ≤400 copies/ml& | 13.6 (5.2,35.3) | 7.5 (2.3,24.4) | 9.4 (1.2,76.6) | * | 15.6 (5.2,46.4) | 10.9 (2.4,48.8) |

| On ART | 2.3 (1.5,3.5) | * | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | * | 2.7 (1.3,5.3) | * |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Lung Disease# | 1.9 (1.01,3.5) | * | 2.4 (1.02,5.5) | * | 1.5 (0.6, 3.9) | * |

| Kidney Disease# | 3.5 (2.1,6.0) | * | 3.5 (1.7,7.3) | 4.9 (1.4,17.8) | 3.1 (1.4,7.2) | * |

| Depression | 1.6 (0.8, 3.2) | * | 2.5 (0.9,6.6) | * | 0.95 (0.4, 2.5) | * |

| Substance Abuse# | 1.9 (1.1,3.6) | * | 3.7 (1.5,9.5) | * | 0.9 (0.4, 2.1) | * |

| Diabetes | 2.3 (1.2,4.5) | * | 2.0 (0.7,5.5) | * | 1.9 (0.7, 5.0) | * |

| Liver Disease# | 3.6(2.4,5.4) | 4.5 (2.2,9.3) | 2.4 (1.4,4.3) | 4.4 (1.5,12.7) | 4.3 (2.2,8.3) | 7.5 (2.4,23.4) |

| Cardiovascular Disease# | 2.9 (1.8,4.6) | 4.2 (1.8,9.9) | 1.8 (0.9,3.5) | * | 4.6 (2.0,10.3) | 6.8 (1.9,24.0) |

: Univariate logistic regression

: Multivariable stepwise Logistic regression; variables denoted with an

did not remain in the multivariable stepwise model

Italicized font signifies significant factors

Kidney disease = CKD or Dialysis

Liver Disease = Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C infection or Liver Cirrhosis

Lung Disease = COPD or Asthma

Cardiovascular Disease = CHF or CAD or HTN

Substance Abuse is Polysubstance abuse or Alcohol abuse

: There were 5 AIDS deaths in patients with CD4>200 cells/mm3 (3 Early era; 2 Late era) hence the 95% CI are wide

: There were 5 AIDS deaths in patients with vL≤400 copies/ml (1 Early era; 4 Late era) hence the 95% CI are wide

In the early ART era (1995-2001), only CD4 count, renal disease, and cardiovascular disease were independently associated with non-AIDS deaths; last CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 in the year prior to death was associated most strongly (OR = 17.4; 3.4, 88.3) with non-AIDS death while again, gender and race were not significant correlates of non-AIDS death.

In the late ART era (2002-2011), similar to those for the entire 17-year time period, independent correlates of non-AIDS deaths included last CD4 <200 cells/mm3 in the year prior to death, VL≤400 copies/ml in the last year prior to death, and liver and cardiovascular disease. Last CD4 count > 200 cells/mm3 in the year prior to death (OR =25.9; 5, 134.5) was most strongly correlated with non-AIDS deaths in the late ART era. Non-white patients had a lower likelihood of non-AIDS related death (OR = 0.4; 0.2, 0.8), but this was not significant on multivariable regression analysis. Gender difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated changes in the causes of death among HIV-infected hospitalized patients from 1995 to 2011. To our knowledge, this is the longest duration retrospective analysis of in-hospital deaths among HIV-infected patients during the ART era. Knowledge of the changes in comorbidities and causes of death among hospitalized HIV-infected patients during the ART era could help inpatient providers focus diagnostic and therapeutic efforts and improve overall care. Our findings emphasize that HIV-infected patients remain at high risk for complications from non-AIDS infections, even when their immune system has been restored as measured by the CD4 cell count, and at increased risk of cardiovascular and liver disease, which highlights the need to carefully monitor HIV-positive patient admitted with these conditions.

Comparison of AIDS related and non-AIDS related deaths in two time periods has revealed important findings. First, inpatient deaths of HIV-infected patients have decreased dramatically (from 6.2% to 1.5%, p<0.0001) and the mortality due to non-AIDS related causes has increased significantly over time. Second, we defined demographic and clinical characteristics independently associated with HIV-infected inpatient mortality. Third, a substantial proportion of in-hospital deaths were caused by potentially preventable non-AIDS as well as AIDS related diseases.

The striking decline in hospital deaths over time is likely the result of expanded ART use resulting in improved immunologic profiles. Non-AIDS related causes were responsible for almost three quarters of deaths in this large inpatient HIV-positive population during the late ART era. Similar findings have been reported from other settings in industrialized countries.5,7,16-18,26,27 In our urban population, although cardiovascular disease, liver disease, renal failure, and malignancy were frequent causes of non-AIDS death, the most common cause was non-AIDS infection. Further, the proportion of deaths due to non-AIDS infections did not decrease significantly over time.

A similar study of HIV-positive inpatients in New York City also found that the majority of non-AIDS deaths were due to non-AIDS infections in the ART era17. The most common causes of non-AIDS infection identified in the study were identical to ours: unspecified sepsis followed by non-recurrent bacterial pneumonia and Clostridium difficile infection. Evidence suggests that individuals with HIV infection have multiple immunological defects that not only lead to increased susceptibility to bacterial infection but also to an unregulated inflammatory response, even in patients who are on ART and virologically suppressed.28,29 This highlights the need for hospital physicians to evaluate an HIV-infected patient's risk for more routine infections that are not commonly considered AIDS related in addition to traditional opportunistic infections. It also implies that inpatient providers should carefully monitor HIV-positive patients admitted for bacterial infections as they remain at higher risk for the development of septic shock.

Cardiovascular and liver disease represented the next most common causes of death, which is similar to the NYC study and consistent with other studies from the ART era.15-18 Although deaths due directly to cardiovascular and liver disease did not significantly change over time, these represented the major comorbidities associated with non-AIDS mortality and, along with renal disease, increased significantly over the study period. There are accumulating studies indicating that HIV infection is associated with accelerated coronary artery disease due to the immune and inflammatory response to the viral replication.30 Additionally, ART side effects such as hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance contribute to an increased cardiovascular risk profile.31 Our findings emphasize the importance of assessing comorbidities not classically considered HIV-related. For example, acute coronary syndrome should be in the differential diagnosis for HIV-infected patients admitted with chest pain regardless of age. Furthermore, HIV-infected patients are at increased risk for hepatitis B and C coinfection due to related behavioral risk, and coinfection is associated with rapid progression to liver cirrhosis 32-34 and increased risk for oncogenesis over time.35,36

Although the numbers are relatively small, non-AIDS malignancy deaths more than quadrupled from the early to the late ART eras. This finding likely underestimates the proportion of overall hospital deaths due to non-AIDS malignancies given the increased use of hospice facilities and community-based care, 38 though it is consistent with increasing trends noted in other studies. 39 Doubling of malignancy as a cause of death among AIDS patients from 2000-2010 was reported in a French study, as well as in a large multi-cohort study from 1999-2011, consistent with our findings.16,40 Developing and implementing screening guidelines for non-AIDS malignancy among those with HIV at the primary care level may potentially reduce this upward trend.41 Inpatient providers need to be aware of this trend and consider undiagnosed non-AIDS malignancy as part of their differential diagnosis when evaluating HIV-positive patients.

While emphasis has been placed on non-AIDS causes, nearly one half of all deaths for the entire period and almost one-third of deaths in the late ART era were still due to AIDS-related causes. This is similar to a study of 40,000 patients in Europe and North America 1996-2006 where AIDS deaths comprised almost half of all deaths, 7 as well as a French national study, 16 and remains characteristic of resource-limited settings.42 This indicates the need for continued vigilance toward earlier HIV case detection and retention in care to prevent disease progression and AIDS related mortality. Primary care and hospital physicians should assess risk for HIV infection in all patients and institute universal HIV testing in both the inpatient and outpatient setting.

Although the majority of our sample was non-white and male, there was sufficient demographic diversity to determine that race and gender differences were not statistically significant contributors to mortality. In contrast, hospital-based and population-based studies reporting racial and gender disparities in HIV-associated mortality have attributed this to poor access to health care.9,17,43-46 Compared to the NYC study, patients in our study had comparable median age and CD4 cell count but also had greater ART use and better virologic control.17 We speculate that in our smaller urban area, characterized by strong community and clinical HIV programs, patients may have had improved access to care without regard to race and gender.

Our study strengths include a large sample size, a diverse population with a relatively high proportion of women and varied age and race, as well as data acquired in a standardized fashion over a prolonged period of ART availability. Further, two clinicians classified causes of death independently, utilizing validated definitions to minimize bias. Our late ART era evaluation is consistent with other HIV cohort studies25 though we utilized multivariate analysis to uncover independent correlates of mortality, a feature not employed in other studies.16,17

We also recognize several limitations in our study. Our study design was associated with the recognized limitations of retrospective research, including missing data. We examined in-hospital deaths at a single urban hospital in the Northeastern United states only, affecting the generalizability of our findings. The study did not include a control group of hospitalized HIV-infected patients who survived or hospitalized HIV-negative patients who died, which might have further strengthened our findings. Despite these limitations, this study provides important observations that can inform strategies to impact HIV-associated mortality in the inpatient setting.

In conclusion, the mortality profile of hospitalized HIV-infected patients has evolved with the epidemic. Caring for the hospitalized HIV-infected patient has become increasingly complex since patients are more likely to suffer from multiple comorbidities, especially cardiovascular and liver diseases, and to die from non-AIDS causes. Inpatient providers need to understand the changing trends in chronic HIV disease management as patients are living longer with antiretroviral therapy and are increasingly likely to succumb to non-AIDS related causes of death. Clinicians can no longer remain focused on AIDS defining opportunistic infections and need to recognize the emerging importance of chronic comorbidities when developing a differential diagnosis, and the higher risk of death due to non-AIDS infectious causes. Physicians caring for hospitalized patients should appreciate the current trends in the HIV epidemic in order to provide comprehensive and appropriate interventions that can reduce mortality for HIV-infected inpatients.

Acknowledgments

Funders: This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (SS; 1K23AI089260).

Bibliography

- 1.Bhaskaran K, Hamouda O, Sannes M, et al. Changes in the risk of death after HIV seroconversion compared with mortality in the general population. JAMA. 2008;300:51–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore RD, Keruly JC, Bartlett JG. Improvement in the health of HIV-infected persons in care: reducing disparities. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;55:1242–51. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodger AJ, Lodwick R, Schechter M, et al. Mortality in well controlled HIV in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the SMART and ESPRIT trials compared with the general population. Aids. 2013;27:973–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cae9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwahlen M, Harris R, May M, et al. Mortality of HIV-infected patients starting potent antiretroviral therapy: comparison with the general population in nine industrialized countries. International journal of epidemiology. 2009;38:1624–33. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. JAIDS. 2006;43:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masia M, Padilla S, Alvarez D, et al. Risk, predictors, and mortality associated with non-AIDS events in newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients: role of antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2013;27:181–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835a1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort C. Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996-2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1387–96. doi: 10.1086/652283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhaus J, Angus B, Kowalska JD, et al. Risk of all-cause mortality associated with nonfatal AIDS and serious non-AIDS events among adults infected with HIV. AIDS. 2010;24:697–706. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283365356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemly DC, Shepherd BE, Hulgan T, et al. Race and sex differences in antiretroviral therapy use and mortality among HIV-infected persons in care. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2009;199:991–8. doi: 10.1086/597124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simard EP, Fransua M, Naishadham D, Jemal A. The influence of sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment on human immunodeficiency virus death rates among adults, 1993-2007. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172:1591–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Rates of hospitalizations and associated diagnoses in a large multisite cohort of HIV patients in the United States, 1994-2005. Aids. 2008;22:1345–54. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328304b38b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crum-Cianflone NF, Grandits G, Echols S, et al. Trends and causes of hospitalizations among HIV-infected persons during the late HAART era: what is the impact of CD4 counts and HAART use? Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2010;54:248–57. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181c8ef22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachhuber MA, Southern WN. Hospitalization rates of people living with HIV in the United States, 2009. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974) 2014;129:178–86. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crum N, Riffenburgh R, Wegner S, et al. Comparisons of Causes of Death and Mortality Rates Among HIV-Infected Persons: Analysis of the Pre-, Early, and Late HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy) Eras. JAIDS. 2006;41:194–200. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179459.31562.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morlat P, Roussillon C, Henard S, et al. Causes of death among HIV-infected patients in France in 2010 (national survey): trends since 2000. AIDS. 2014;28:1181–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JH, Psevdos G, Jr, Gonzalez E, Singh S, Kilayko MC, Sharp V. All-cause mortality in hospitalized HIV-infected patients at an acute tertiary care hospital with a comprehensive outpatient HIV care program in New York City in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Infection. 2013;41:545–51. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Annals Internal Medicine. 2006;145:397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connecticut Department of Public Health T, HIV, STD & Viral Hepatitis Section. Epidemiologic Profile of HIV in Connecticut. 2013:2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Center for Infectious Disease Research. Coding of Death in HIV Project. 2004 http://www.cphiv.dk/Tools-Standards/CoDe.

- 21.Kowalska JD, Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, et al. A standardized algorithm for determining the underlying cause of death in HIV infection as AIDS or non-AIDS related: results from the EuroSIDA study. HIV Clinical Trials. 2011;12:109–17. doi: 10.1310/hct202-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro K, Ward J, Slutsker L, et al. Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults. MMWR. 1993:41. 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider MF, Gange SJ, Williams CM, et al. Patterns of the hazard of death after AIDS through the evolution of antiretroviral therapy: 1984-2004. AIDS. 2005;19:2009–18. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000189864.90053.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima VD, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, et al. Continued improvement in survival among HIV-infected individuals with newer forms of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:685–92. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802ef30c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Justice AC, Modur SP, Tate JP, et al. Predictive accuracy of the Veterans Aging Cohort Study index for mortality with HIV infection: a North American cross cohort analysis. JAIDS. 2013;62:149–63. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827df36c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marin B, Thiebaut R, Bucher HC, et al. Non-AIDS-defining deaths and immunodeficiency in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2009;23:1743–53. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e9b78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehren K, Hertenstein C, Kummerle T, et al. Causes of death in HIV-infected patients from the Cologne-Bonn cohort. Infection. 2014;42:135–40. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0535-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordano Q, Falco V, Almirante B, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in patients infected with HIV: still a threat in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;38:1623–8. doi: 10.1086/420933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huson MA, Grobusch MP, van der Poll T. The effect of HIV infection on the host response to bacterial sepsis. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2015;15:95–108. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70917-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:614–22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Triant VA. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Rev Cardiovascular Medicine. 2014;15(Suppl 1):S1–8. doi: 10.3908/ricm15S1S002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaslightwala I, Bini EJ. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the prevalence and severity of steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:1026–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, et al. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562–9. doi: 10.1086/321909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim AY, Chung RT. Coinfection with HIV-1 and HCV--a one-two punch. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:795–814. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puoti M, Bruno R, Soriano V, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected patients: epidemiological features, clinical presentation and outcome. Aids. 2004;18:2285–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brau N, Fox RK, Xiao P, et al. Presentation and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected patients: a U.S.-Canadian multicenter study. J Hepatol. 2007;47:527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 Weeks for Chronic HCV without Cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:1879–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selwyn PA, Goulet JL, Molde S, et al. HIV as a chronic disease: implications for long-term care at an AIDS-dedicated skilled nursing facility. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2000;77:187–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02390530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart A, Chan Carusone S, To K, Schaefer-McDaniel N, Halman M, Grimes R. Causes of Death in HIV Patients and the Evolution of an AIDS Hospice: 1988-2008. AIDS Research Treatment. 2012;2012:390406. doi: 10.1155/2012/390406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384:241–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60604-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mani D, Aboulafia DM. Screening guidelines for non-AIDS defining cancers in HIV-infected individuals. Current Opinion Oncology. 2013;25:518–25. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328363e04a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewden C, Drabo YJ, Zannou DM, et al. Disease patterns and causes of death of hospitalized HIV-positive adults in West Africa: a multicountry survey in the antiretroviral treatment era. Journal International AIDS Society. 2014;17:18797. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davalos DM, Hlaing WM, Kim S, de la Rosa M. Recent trends in hospital utilization and mortality for HIV infection: 2000-2005. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2010;102:1131–8. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hlaing WM, McCoy HV. Differences in HIV-related hospitalization among white, black, and Hispanic men and women of Florida. Women & health. 2008;47:1–18. doi: 10.1080/03630240802092126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palacio H, Kahn JG, Richards TA, Morin SF. Effect of race and/or ethnicity in use of antiretrovirals and prophylaxis for opportunistic infection: a review of the literature. Public Health Reports. 2002;117:233–51. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.3.233. discussion 1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stone VE. HIV/AIDS in Women and Racial/Ethnic Minorities in the U.S. Curr Infectious Disease Reports. 2012;14:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greene M, Justice AC, Lampiris HW, Valcour V. Management of human immunodeficiency virus infection in advanced age. JAMA. 2013;309:1397–405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]