Abstract

Background

There is a need to identify patients with diabetic kidney disease (DKD) using non-invasive, cost-effective screening tests. Sudoscan®, a device using electrochemical skin conductance (ESC) to measure sweat gland dysfunction, is valuable for detecting peripheral neuropathy. ESC was tested for association with DKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 ml/min/1.73m2) in 383 type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D)-affected patients; diagnostic thresholds were determined in 540 patients.

Methods

Relationships between ESC with eGFR and urine albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR) were assessed in 202 European Americans (EA) and 181 African Americans (AA) with T2D.

Results

In 92 EA DKD cases and 110 T2D non-nephropathy controls, respectively, mean(SD) ages were 68.9(9.8) and 61.1(10.8) years, HbA1c 7.4(1.2) and 7.4(1.3)%, eGFR 29.5(12.2) and 87.7(14.1) ml/min/1.73m2, and UACR 1227(1710) and 7.6(5.9) mg/g. In 57 AA cases and 124 controls, respectively, mean (SD) ages were 64.0(12.0) and 59.5(9.7) years, HbA1c 7.4(1.3) and 7.6 (1.7)%, eGFR 29.7(13.3) and 90.2(16.2) ml/min/1.73m2, and UACR 1172(1564) and 7.8(7.1) mg/g. Mean(SD) ESC (μS) was lower in cases than controls (EA: case/control hands 49.3(18.5)/62.4(16.2); feet 62.2(18.0)/73.4(13.9), both p<5.8×10−7; AA: case/control hands 39.8(19.0)/48.5(17.1); feet 53.2(21.3)/63.5(19.4), both p≤0.01). Adjusting for age, sex, BMI and HbA1c, hands and feet ESC associated with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 (p≤7.2×10−3), UACR >30 mg/g (p≤7.0×10−3), UACR >300 mg/g (p≤8.1×10−3), and continuous traits eGFR and UACR (both p≤5.0×10−9). HbA1c values were not useful for risk stratification.

Conclusions

ESC measured using Sudoscan® is strongly associated with DKD in AA and EA. ESC is a useful screening test to identify DKD in patients with T2D.

Keywords: African Americans, albuminuria, diabetes mellitus, electrochemical skin conductance, European Americans, kidney disease

Introduction

Diabetic microvascular complications cause severe hardship for patients and their families, as well as strain global healthcare delivery systems.[1] Patients with sub-optimal glycemic control commonly develop diabetic retinopathy, a microvascular complication, whereas, a smaller proportion develop diabetic kidney disease (DKD).[2] Familial aggregation of DKD supports an etiologic role for inherited (biologic) factors in its susceptibility, beyond a hyperglycemic environment.[3;4] Given that rates of type 2 diabetes (T2D) are increasing worldwide and approximately 20-40% of patients with longstanding T2D develop DKD, non-invasive highly accurate screening tests to detect which patients with T2D are at high risk for DKD would be useful. Earlier detection of nephropathy will increase the likelihood that treatments such as improving glycemic and hypertension control and use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS) blocking agents can delay nephropathy progression and reduce associated cardiovascular complications.[5;6] Many patients with DKD do not have albuminuria.[7] Therefore, it is critical that screening tests be able to detect reduced estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR).

Electrochemical skin conductance (ESC) to measure sweat gland dysfunction has proven useful for detecting and monitoring peripheral and autonomic neuropathic complications in patients with T2D.[8;9] In addition to diabetic neuropathy, two reports measuring ESC with the Sudoscan® device showed association with DKD.[10;11] As such, there may be benefit to measuring ESC in patients with T2D to non-invasively identify those likeliest to have DKD. Urine testing for albuminuria, measurement of serum creatinine concentration, and eGFR can then be performed in individuals with reduced ESC, decreasing the need for conducting these more expensive tests in the broader population. Because ESC can be non-invasively measured at low cost, large numbers of T2D-affected patients can rapidly be screened and the high-risk subset referred for further renal (and neurologic) evaluation. Strategies such as this may improve early detection and monitoring of DKD, with the potential to reduce progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) requiring renal replacement therapy and decrease associated cardiovascular complications. The present analyses measured ESC in African Americans and European Americans with T2D to detect associations with DKD and develop threshold values useful in the clinic.

Methods

Study populations

The study population was comprised of self-described African Americans and European Americans with T2D recruited from the Diabetes Heart Study, the African-American Diabetes Heart Study, internal medicine, and nephrology clinics at Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSM).[12;13] Inclusion criteria were diabetes mellitus diagnosed after the age of 25 years and active hyperglycemic treatment with oral agents and/or insulin in the absence of diabetic ketoacidosis. CKD was attributed to diabetes after medical record review by a single investigator (BIF), based on nephropathy first detected after ≥5 year diabetes duration in the absence of other known causes of kidney disease. In the primary analyses, presence of nephropathy was based on a Chronic Kidney Disease–Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 (irrespective of the level of proteinuria) in newly recruited DKD cases.[14] Secondary analyses were then performed including all DKD cases from the primary analyses, as well as previously recruited DKD cases based on the definition of a UACR >30 m/g and/or CKD-EPI eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2.[11] T2D non-nephropathy controls in the primary and secondary analyses were the same subjects, all with eGFR >60 ml/min/1.73m2 and UACR <30 mg/g.

Exclusion criteria included amputations (precluding accurate ESC testing), presence of cardiac pacemakers and/or implanted defibrillators, malignancy (except non-melanoma skin cancer) within the prior year, receipt of chemotherapy within the prior year, prior dialysis treatments, or kidney transplantation. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at WFSM.

Laboratory testing

Laboratory testing included assessment of glycemic control based on the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and measurement of serum creatinine concentration using a kinetic modification of the Jaffe procedure (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. Spot urine albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured at LabCorp, Inc. (Burlington, NC) for computation of the urine albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR).

Electrochemical skin conductance (ESC)

As previously reported, ESC was measured using the Sudoscan® device (Impeto Medical; Paris, France) during routine clinic visits to assess sweat gland dysfunction.[11;15] ESC was measured through extraction of chloride ions from sweat glands on the palms and soles (reverse iontophoresis) and chronoamperometry. Both palms and soles were cleansed with a moist towel and placed on two large stainless steel electrodes that had been disinfected with Surfa'Safe® (Laboratoires Anios; Lille-Hemmes, France). Participants were asked not to move during the approximate two minute test. Electrodes were connected to a computer that recorded time/ampere curves as gentle stimulation was applied in a graded fashion via low voltage direct current (<4 volts) on the anode. This generated a voltage through reverse iontophoresis on the cathode that is proportional to the flow of sweat gland chloride ions. The ratio between the generated current and the constant voltage applied, also known as the ESC, was measured in microsiemens (μS) between anode and cathode. Values were computed for skin conductance in each palm and each sole, and as a measure of asymmetry between the two hands and the two feet. Mean ESC in the hands, mean ESC in the feet, and mean global skin conductance computed as 0.5*(reflecting [right + left hand]/2 + [right and left foot]/2) in each participant were evaluated for association with eGFR and UACR.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive summary statistics were computed separately by presence of kidney disease and race/ethnicity. Unadjusted comparisons of the distribution of observed conductance and other demographics variables were performed between race/ethnicity by kidney disease status. For continuous outcomes, these comparisons were based upon the Wilcoxon two-sample test, a non-parametric test known to be robust to deviations from the normality assumption. Chi-square tests were used for comparing categorical outcomes by kidney disease status.

Generalized linear models (GLM) were fitted to test for associations between mean skin conductance and kidney function measures. CKD-EPI eGFR values above 120 ml/min/1.73/m2 were winsorized at 120. The Box-Cox method was applied to identify the appropriate transformation best approximating the distributional assumptions of conditional normality and homogeneity of variance of the residuals.[16] These methods suggested taking the logarithm of UACR. There was no need to transform the CKD-EPI eGFR. We ran an unadjusted model to test for association between urine ACR and CKD-EPI GFR followed by adjusted models that successively included age, gender, HbA1c and body mass index (BMI) as covariates. Analyses were run stratified by race/ethnicity to protect against the potential confounding effect of race/ethnicity.

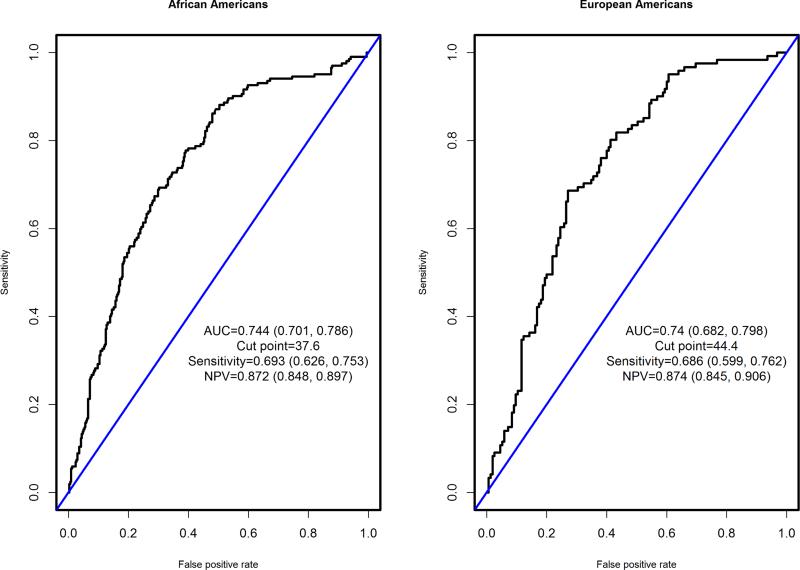

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated using the predicted probabilities generated from a logistic regression model with the log-odds of eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73/m2 as the outcome and participant age and mean ESC in feet as predictors. This model was developed and analyzed because it yielded predicted probabilities that were strongly correlated with a proprietary DKD measure that is provided by the Sudoscan® device (absolute value of the Spearman rank correlation 0.96). The (0, 1) point on the ROC curve corresponds to the 1-sensitivity and specificity of the ideal diagnostic test that correctly classifies all diseased and all disease-free individuals.[17];[18] The point closest to (0, 1) has recently been shown to outperform other competing approaches, especially when the distribution of the biomarker is skewed.[19] The estimated cut-point, specificity, sensitivity, negative predicted probability (NPV), and positive predicted probability (PPV) were computed.

Results

The primary analyses contrasted ESC in 149 newly recruited DKD cases with an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (92 African American; 57 European American) with those in 234 T2D non-nephropathy controls with eGFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and UACR <30 mg/g (124 African American; 110 European American). The 149 cases and one new control (total 150 new participants) were enrolled between March 11, 2014 and April 10, 2015. Among controls, 233 (of 234) were enrolled between February 14, 2012 and March 29, 2013, as reported.[11]

Table 1 displays demographic, laboratory, and Sudoscan® ESC measures in European American and African American cases and controls. DKD cases from both race-groups were older and had higher systolic blood pressures than controls. European American cases had higher diastolic blood pressures and African American cases had a higher body mass index (BMI) than their respective controls. Mean eGFR was 29.6 and 87.8 ml/min/1.73m2 in European American cases and controls, respectively; 29.6 and 90.2 ml/min/1.73m2 in African American cases and controls. Although albuminuria was not an inclusion criterion for cases in the primary analyses, UACR values >30 mg/g and >300 mg/g, respectively, were detected in 84.3% and 53.9% of European American cases and 100% and 59.3% of African American cases (median UACR was 730 mg/g in African American cases and 457 mg/g in European American cases). Table 1 displays statistically significant reductions in ESC in European American cases and African American cases, compared to race-matched controls for all measures (mean feet, mean hands, and global [mean of hands and feet] skin conductance).

Table 1.

Demographic data in cases with diabetic kidney disease and type 2 diabetic non-nephropathy controls, by race

| Variable | European American | African American | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Kidney Function (N=110) | Diabetic Kidney Disease (N=92) | P-value | Normal Kidney Function (N=124) | Diabetic Kidney Disease (N=57) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 61 (10.8) 60 | 69 (9.7) 69.2 | 3.6×10−7 | 59.5 (9.7) 60.1 | 64 (11.9) 64.4 | 0.01 |

| Female (%) | 48.6 (50.2) 0 | 37.6 (48.7) 0 | 0.12 | 51.6 (50.2) 100 | 61.4 (49.1) 100 | 0.22 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 34.1 (6.7) 33.9 | 33.7 (7.8) 32.6 | 0.37 | 33.5 (7.4) 31.7 | 36.5 (7.2) 35.3 | 3.5×10−3 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 124.1 (14.5) 122 | 143.3 (21.3) 140 | 1.4×10−11 | 128.2 (17.6) 125 | 150.8 (23.6) 147 | 5.0×10−10 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74.6 (9.4) 75 | 68.7 (11.4) 67 | 9.2×10−5 | 75.3 (11.1) 75 | 74.7 (13.9) 73 | 0.34 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.4 (1.3) 7 | 7.4 (1.2) 7.3 | 0.53 | 7.5 (1.7) 7 | 7.4 (1.3) 7.3 | 0.96 |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 87.8 (14.2) 87.9 | 29.6 (12.2) 28 | 2.9×10−34 | 90.2 (16.2) 88.9 | 29.6 (13.3) 27.8 | 6.2×10−27 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 (0.2) 0.8 | 2.4 (1.4) 2 | 4.5×10−34 | 0.9 (0.2) 0.9 | 2.7 (1.6) 2.3 | 4.3×10−26 |

| Urine albumin:creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 7.5 (5.8) 6.1 | 1213.8 (1704.7) 452.1 | 2.1×10−29 | 7.8 (7.1) 5.1 | 1171.8 (1546.4) 730.1 | 3.2×10−26 |

| Global electrochemical skin conductance, (μS)1 | 67.9 (13) 71 | 55.8 (16.2) 58.5 | 2.4×10−8 | 56 (16.9) 60.5 | 46.5 (18.8) 50 | 1.9×10−3 |

| Mean feet ESC (μS) | 73.6 (13.8) 77 | 62.1 (17.9) 64 | 5.7×10−8 | 63.5 (19.4) 71 | 53.2 (21.3) 56 | 1.6×10−3 |

| Mean hand ESC (μS) | 62.3 (16.2) 66 | 49.5 (18.5) 52 | 1.3×10−6 | 48.5 (17.1) 51 | 39.8 (19) 46 | 7.0×10−3 |

| Sudoscan-DKD measurement | 62.0 (15.5) 62 | 46.8 (12.8) 47 | 7.8×10−12 | 58.4 (13.3) 59 | 50 (14.8) 49 | 3.6×10−14 |

Defined as mean of (hands + feet) conductance

2 ESC = electrochemical skin conductance

Table 2 displays the results of continuous relationships between eGFR and log UACR with measures of ESC; the initial model was unadjusted, followed sequentially by models adjusting for age and gender; age, gender, and BMI; and a full-model including age, gender, BMI, and HbA1c. Significant relationships between hands ESC, feet ESC, and global ESC with eGFR were seen in all models including the fully-adjusted model in African Americans and European Americans. In contrast, log UACR was only associated with ESC in European Americans. A meta-analysis was performed across race-groups and revealed highly significant results for ESC association with eGFR and UACR (Table 2). Association results were always in the same direction in both race/ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Continuous outcome analyses between electrochemical skin conductance and parameters of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes

| Outcome | Predictor | Adjustment | African American | European American | Meta-analysis | SD of predictor | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Effect1 | SE | P-value | β | Effect1 | SE | P-value | sign | β | SE | P-value | AA | EA | |||

| eGFR | Global | None | 0.53 | 2.38 | 0.13 | 5.6×10−5 | 0.77 | 3.05 | 0.13 | 1.9×10−8 | ++ | 0.65 | 0.09 | 1.8×10−12 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| eGFR | Global | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | 0.48 | 2.17 | 0.12 | 1.3×10−4 | 0.67 | 2.63 | 0.12 | 1.4×10−7 | ++ | 0.58 | 0.09 | 3.2×10−11 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| eGFR | Feet | None | 0.43 | 2.19 | 0.11 | 2.2×10−4 | 0.65 | 2.71 | 0.13 | 7.2×10−7 | ++ | 0.52 | 0.08 | 4.7×10−10 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| eGFR | Feet | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | 0.40 | 2.04 | 0.11 | 3.1×10−4 | 0.53 | 2.24 | 0.12 | 7.0×10−6 | ++ | 0.46 | 0.08 | 5.0×10−9 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| eGFR | Hands | None | 0.50 | 2.25 | 0.13 | 1.4×10−4 | 0.60 | 2.74 | 0.11 | 5.1×10−7 | ++ | 0.55 | 0.09 | 1.0×10−10 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| eGFR | Hands | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | 0.44 | 1.99 | 0.12 | 5.0×10−4 | 0.53 | 2.43 | 0.11 | 1.4×10−6 | ++ | 0.49 | 0.08 | 1.1×10−9 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| eGFR | Sudoscan-DKD | None | 0.87 | 3.10 | 0.16 | 8.9×10−8 | 1.07 | 4.35 | 0.12 | 4.1×10−17 | ++ | 1.00 | 0.09 | 7.0×10−27 | 14.3 | 16.2 |

| eGFR | Sudoscan-DKD | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | 0.79 | 2.81 | 0.28 | 6.3×10−3 | 1.11 | 4.49 | 0.22 | 1.6×10−6 | ++ | 0.99 | 0.18 | 2.0×10−8 | 14.3 | 16.2 |

| Log UACR | Global | None | −0.03 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 4.7×10−3 | −0.07 | −0.27 | 0.01 | 3.0×10−10 | -- | −0.05 | 0.01 | 3.7×10−11 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| Log UACR | Global | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 4.1×10−3 | −0.07 | −0.27 | 0.01 | 5.1×10−10 | -- | −0.05 | 0.01 | 3.6×10−11 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| Log UACR | Feet | None | −0.02 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 4.3×10−3 | −0.06 | −0.24 | 0.01 | 3.1×10−8 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 3.4×10−9 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| Log UACR | Feet | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 3.5×10−3 | −0.05 | −0.23 | 0.01 | 1.9×10−7 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 8.6×10−9 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| Log UACR | Hands | None | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 1.7×10−2 | −0.05 | −0.24 | 0.01 | 2.1×10−8 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 3.1×10−9 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| Log UACR | Hands | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 1.7×10−2 | −0.05 | −0.25 | 0.01 | 8.5×10−9 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 1.1×10−9 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| Log UACR | Sudoscan-DKD | None | −0.04 | −0.15 | 0.01 | 6.5×10−4 | −0.06 | −0.25 | 0.01 | 8.8×10−9 | -- | −0.05 | 0.01 | 8.4×10−12 | 14.3 | 16.2 |

| Log UACR | Sudoscan-DKD | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.06 | −0.21 | 0.02 | 9.3×10−3 | −0.11 | −0.45 | 0.02 | 2.1×10−8 | -- | −0.09 | 0.01 | 7.3×10−10 | 14.3 | 16.2 |

Effect corresponding to a quarter standard deviation (SD) increase in the predictor

β=parameter estimate; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; UACR=urine albumin:creatinine ratio; SE=standard error; AA=African American; EA=European American

Results of the logistic regression analyses assessing relationships between ESC and UACR >30 mg/g, UACR >300 mg/g, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2, and presence of DKD defined as an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 and/or UACR >30 mg/g are presented in Table 3. The same adjustments were applied as in the analysis of continuous outcomes. Hands ESC, feet ESC, and global ESC were significantly associated with UACR >30 mg/g, UACR >300 mg/g, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2, and with DKD in both race-groups.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analyses between electrochemical skin conductance and parameters of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes

| Outcome | Predictor | Adjustment | African American | European American | Meta-analysis | SD of predictor | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR1 | SE | P-value | β | OR | SE | P-value | sign | β | SE | P-value | AA | EA | |||

| UACR>30 | Global | None | −0.028 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 2.6×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 2.6×10−5 | -- | −0.035 | 6.98×10−3 | 7.0×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| UACR>30 | Global | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.030 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 3.0×10−3 | −0.04 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 1.0×10−4 | -- | −0.036 | 7.55×10−3 | 7.5×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| UACR>30 | Feet | None | −0.023 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 4.3×10−3 | −0.04 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 2.0×10−4 | -- | −0.028 | 6.19×10−3 | 6.2×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| UACR>30 | Feet | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.025 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 4.9×10−3 | −0.03 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 8.4×10−4 | -- | −0.029 | 6.67×10−3 | 6.7×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| UACR>30 | Hands | None | −0.026 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 5.1×10−3 | −0.03 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 1.0×10−4 | -- | −0.030 | 6.38×10−3 | 6.4×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| UACR>30 | Hands | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.028 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 6.6×10−3 | −0.03 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 2.9×10−4 | -- | −0.031 | 6.95×10−3 | 7.0×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| UACR>30 | Sudoscan-DKD | None | −0.05 | 0.85 | 0.01 | 3.5×10−4 | −0.06 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 1.7×10−7 | -- | −0.06 | 0.01 | 3.7×10−10 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| UACR>30 | Sudoscan-DKD | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.05 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 2.7×10−4 | -- | −0.07 | 0.02 | 5.1×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| UACR>300 | Global | None | −0.026 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.78 | 0.01 | 3.4×10−7 | -- | −0.041 | 1.35×10−2 | 8.0×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| UACR>300 | Global | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.031 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 2.5×10−7 | -- | −0.047 | 1.46×10−2 | 8.6×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| UACR>300 | Feet | None | −0.022 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 1.2×10−5 | -- | −0.032 | 1.15×10−2 | 6.9×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| UACR>300 | Feet | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.026 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 1.1×10−5 | -- | −0.036 | 1.23×10−2 | 7.3×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| UACR>300 | Hands | None | −0.024 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 8.5×10−7 | -- | −0.038 | 9.09×10−3 | 7.5×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| UACR>300 | Hands | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.029 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.78 | 0.01 | 5.0×10−7 | -- | −0.044 | 2.26×10−2 | 8.1×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| UACR>300 | Sudoscan-DKD | None | −0.04 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 1.3×10−4 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 5.5×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| UACR>300 | Sudoscan-DKD | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.07 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 5.2×10−6 | -- | −0.11 | 0.02 | 1.3×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| eGFR<60 | Global | None | −0.031 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 8.8×10−4 | −0.06 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 2.9×10−7 | -- | −0.042 | 8.00×10−3 | 7.2×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| eGFR<60 | Global | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.032 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 1.6×10−3 | −0.06 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 1.4×10−6 | -- | −0.043 | 8.57×10−3 | 7.9×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| eGFR<60 | Feet | None | −0.026 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 1.3×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 1.1×10−5 | -- | −0.033 | 6.85×10−3 | 6.4×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| eGFR<60 | Feet | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.027 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 1.7×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 4.5×10−5 | -- | −0.034 | 7.29×10−3 | 6.9×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| eGFR<60 | Hands | None | −0.028 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 2.7×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 9.4×10−7 | -- | −0.037 | 7.54×10−3 | 6.5×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| eGFR<60 | Hands | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.028 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 6.2×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 3.5×10−6 | -- | −0.038 | 8.12×10−3 | 7.2×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| eGFR<60 | Sudoscan-DKD | None | −0.04 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 1.3×10−4 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 5.5×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| eGFR<60 | Sudoscan-DKD | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.07 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 5.2×10−6 | -- | −0.11 | 0.02 | 1.3×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| DKD | Global | None | −0.029 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 1.4×10−3 | −0.06 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 4.9×10−7 | -- | −0.040 | 1.44×10−2 | 7.2×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| DKD | Global | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.030 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 2.8×10−3 | −0.06 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 1.9×10−6 | -- | −0.041 | 1.54×10−2 | 7.8×10−3 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| DKD | Feet | None | −0.024 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 2.1×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 1.4×10−5 | -- | −0.032 | 1.25×10−2 | 6.3×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| DKD | Feet | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.025 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 3.4×10−3 | −0.04 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 5.3×10−5 | -- | −0.033 | 1.31×10−2 | 6.8×10−3 | 20.5 | 16.8 |

| DKD | Hands | None | −0.027 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 3.5×10−3 | −0.04 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 1.8×10−6 | -- | −0.035 | 9.96×10−3 | 6.5×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| DKD | Hands | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.027 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 8.4×10−3 | −0.05 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 5.0×10−6 | -- | −0.036 | 2.68×10−2 | 7.2×10−3 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| DKD | Sudoscan-DKD | None | −0.04 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 1.3×10−4 | -- | −0.04 | 0.01 | 5.5×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

| DKD | Sudoscan-DKD | Age, gender, BMI, HbA1c | −0.07 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 5.2×10−6 | -- | −0.11 | 0.02 | 1.3×10−6 | 14.29 | 16.2 |

Effect corresponding to a quarter standard deviation (SD) increase in the predictor

β = parameter estimate; OR=odds ratio; SE=standard error; UACR=urine albumin:creatinine ratio; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; DKD=diabetic kidney disease defined as eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and/or UACR >30 mg/g; AA=African American; EA=European American.

The secondary analysis incorporated ESC results from all 264 African Americans and 276 European Americans with T2D who had undergone Sudoscan® testing and renal functional assessment at Wake Forest. Results from an additional 157 previously recruited DKD cases were included, along with the cases and controls in the primary analyses. The additional cases had higher mean eGFR and lower UACR than those in the primary analyses, since DKD case inclusion criteria included a UACR >30 mg/g, regardless of eGFR. Supplementary Table S1 contains demographic data in all DKD cases included in the secondary analyses. European Americans and African Americans had mean eGFR values of 47.2 and 57.6 ml/min/1.73m2, respectively; and median UACR was 103 mg/g in African American cases and 99 mg/g in European American cases. UACR values >30 mg/g and >300 mg/g, respectively, were recorded in 100% and 0% of European American cases and 89.8% and 38.0% of African American cases. Although the additional cases included in the secondary analyses had less severe nephropathy than those in the primary analyses, statistically significant associations were detected between feet ESC, hands ESC, and global ESC in both race-groups with eGFR in continuous analyses, and between log UACR in European Americans (Supplementary Table S2). Logistic regression analyses in the full sample revealed significant associations between feet ESC, hands ESC, and global ESC with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 and UACR >300 mg/g in both race-groups (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 4 displays the predicted probability cut-off values for detection of eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 in the full sample of 540 patients with T2D; area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV are reported, by race. Thresholds were developed for this screening test to detect diabetic individuals at high risk for DKD who might benefit from additional lab testing.

Table 4.

Threshold analyses for detection of parameters of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, by race

| Diagnostic performance | African American | European American | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UACR >300 mg/g | eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 | UACR >300 mg/g | eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 | |

| Cut-point | 32.5 | 37.6 | 46.9 | 44.4 |

| AUC | 0.616 (0.556, 0.675) | 0.744 (0.701, 0.786) | 0.644 (0.57, 0.719) | 0.74 (0.682, 0.798) |

| Sensitivity | 0.696 (0.606, 0.774) | 0.693 (0.626, 0.753) | 0.617 (0.49, 0.729) | 0.686 (0.599, 0.762) |

| Specificity | 0.511 (0.463, 0.558) | 0.698 (0.647, 0.745) | 0.642 (0.575, 0.703) | 0.729 (0.654, 0.793) |

| NPV | 0.835 (0.796, 0.878) | 0.872 (0.848, 0.897) | 0.834 (0.79, 0.883) | 0.874 (0.845, 0.906) |

| PPV | 0.322 (0.286, 0.354) | 0.434 (0.384, 0.476) | 0.364 (0.295, 0.421) | 0.458 (0.376, 0.52) |

ESC=electrochemical skin conductance; UACR=urine albumin:creatinine ratio; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; AUC=area under the curve; NPV=negative predicted probability; PPV=positive predicted probability

Figures 1 displays ROC curves and diagnostic performance of the predicted probability of the logistic model that includes age and mean ESC in feet as covariates and eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 as the outcome in African Americans and European Americans with T2D. In African Americans with T2D, the optimal cut-point for predicted probability of detecting an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 was 37.6% with an AUC of 0.74; this threshold had sensitivity of 0.69, specificity of 0.70, and a NPV 0.87. In European Americans with T2D, the optimal cut-point for predicted probability of detecting eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 was 44.4% with an AUC of 0.74; this threshold had a sensitivity of 0.69, a specificity of 0.73, and a NPV 0.87.

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curves of the predicted probability of an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2, based on mean feet electrochemical skin conductance and age in African Americans and European Americans with type 2 diabetes.

Discussion

Given the worldwide epidemic of T2D and associated DKD, validating non-invasive methods for detecting and potentially monitoring diabetic microvascular complications is important. Measures of ESC were associated with DKD in Hong Kong Chinese, with replication in African Americans having milder nephropathy.[10;11] However, assessment of ESC associations with more advanced DKD was not possible in the initial U.S. study. Here, a larger number of African Americans and European Americans with T2D and eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 were recruited and tested. Significant evidence of association was confirmed between both eGFR and albuminuria with ESC measured with the Sudoscan® device in this population having Stages 3 to 5 CKD related to T2D.

In addition, all 540 Wake Forest study participants with T2D tested with the Sudoscan® device were included in a secondary analysis capturing a broader range of kidney function and albuminuria. In African Americans, this analysis revealed predicted probabilities of 37.6% and 44.4% as cut-points with relatively high sensitivity (about 69% in both ethnicities), and NPV >87% for eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2. Race-specific thresholds are necessary based on known differences in ESC in healthy and diabetic African Americans and European Americans.[11] The etiology of the markedly different ESC values in populations with, versus without, recent African ancestry is unknown. However, this observation is reproducible and demonstrates the need to interpret ESC results in a population-specific fashion.

In addition to the utility of ESC for diagnosing and monitoring diabetic peripheral neuropathy and autonomic neuropathy, the results in this report support potential use of ESC for identifying individuals with higher likelihood of DKD in populations with T2D. In contrast, mean HbA1c values between groups did not differ significantly and would not be useful in risk stratification for DKD. Additional studies are warranted to determine whether the rate of decline in eGFR and changes in albuminuria are detectable with the Sudoscan® device for monitoring disease remission or progression with therapy. ESC measurements appear to be useful for screening populations with T2D to detect those likely to have DKD rapidly, and would be applicable in underdeveloped areas without ready access to blood and urine testing for nephropathy. Although urine dipsticks can detect albuminuria, many diabetic patients will develop DKD in the absence of albuminuria and those with low level proteinuria may not lose kidney function. The high reproducibility of ESC testing for detection of reductions in eGFR makes it particularly attractive, compared to more variable measures such as proteinuria.[8] [20;21] We chose to focus association results on the mean ESC in feet and participant age, because of stronger association with eGFR compared to when considering mean ESC in hands or global ESC.

The present analyses included 540 individuals with T2D and simultaneous measures of ESC, kidney function, and albuminuria. Potential limitations include that albuminuria results were based on a single reading and albuminuria can vary over time. This limitation is present in many reports and is expected to have the greatest impact in those with low level albuminuria, where fluctuations can reclassify patients between having microalbuminuria and normoalbuminuria. Therefore, the main analyses focused on the end-point of reduced eGFR and UACR >300 mg/g, because higher UACR values reflects overt proteinuria. The present results were cross-sectional; as such, longitudinal follow-up assessing changes in ESC with progression and /or regression of nephropathy remain necessary. In addition, diagnostic performance may be overly optimistic, because the cut-offs were identified with the same dataset that was used to estimate the predicted probabilities. However, these diagnostic performances were similar to those obtained with the Sudoscan®-DKD measure; this is a proprietary measure that was developed using an independent data set that was not from the Wake Forest School of Medicine. ESC has been extensively assessed in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) for peripheral and autonomic neuropathy; however, studies on nephropathy phenotypes remain to be performed in T1D.

In conclusion, non-invasively measured ESC strongly associated with parameters of kidney disease in African Americans and European Americans with T2D. Race-specific ESC thresholds suggesting reduced kidney function (eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2) and macroalbuminuria (UACR >300 mg/g) are reported with relatively high sensitivity and excellent negative predictive values in individuals with T2D. ESC is likely to be useful for non-invasive screening in populations with diabetes to determine which individuals are likeliest to have nephropathy and would benefit from further laboratory testing and referral. ESC testing will be especially useful in settings where there is limited access to healthcare. Future studies should assess whether changes in ESC are associated with longitudinal change in eGFR and UACR in patients with DKD. This will determine whether a role exists for ESC to monitor progression of DKD, as in neuropathy. This would be valuable in patients who undergo intensification of glycemic and hypertension treatment and institution of RAAS blockade. Reduced ESC is strongly associated with albuminuria and reduced kidney function in African Americans and European Americans with T2D.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Impeto Medical (Paris, France), based on an investigator-initiated research protocol. The sponsor did not receive study results until recruitment was complete, data analyzed, and the manuscript prepared. Dr. Freedman and Wake Forest School of Medicine authors take full responsibility for the reliability of these data. The Diabetes Heart Study and African-American Diabetes Heart Study contributed participants and are supported by NIH grants RO1 NS075107 (BIF, JD), NS058700 (DWB), and DK071891 (BIF). The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

Footnotes

No author reports a conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Seaquist ER. 2014 presidential address: stop diabetes-it is up to us. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:737–742. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, Chiang JL, de Boer IH, Goldstein-Fuchs J, Hirsch IB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Narva AS, Navaneethan SD, Neumiller JJ, Patel UD, Ratner RE, Whaley-Connell AT, Molitch ME. Diabetic kidney disease: a report from an ADA Consensus Conference. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2864–2883. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden DW, Freedman BI. The challenging search for diabetic nephropathy genes. Diabetes. 2012;61:1923–1924. doi: 10.2337/db12-0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pezzolesi MG, Krolewski AS. Diabetic nephropathy: is ESRD its only heritable phenotype? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1505–1507. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de ZD, Remuzzi G, Parving HH, Keane WF, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, Snapinn S, Cooper ME, Mitch WE, Brenner BM. Albuminuria, a therapeutic target for cardiovascular protection in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Circulation. 2004;110:921–927. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139860.33974.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de ZD. Albuminuria, not only a cardiovascular/renal risk marker, but also a target for treatment? Kidney Int Suppl. 2004:S2–S6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Roshan B, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. In patients with type 1 diabetes and new-onset microalbuminuria the development of advanced chronic kidney disease may not require progression to proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2010;77:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casellini CM, Parson HK, Richardson MS, Nevoret ML, Vinik AI. Sudoscan, a noninvasive tool for detecting diabetic small fiber neuropathy and autonomic dysfunction. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15:948–953. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AG, Lessard M, Reyna S, Doudova M, Singleton JR. The diagnostic utility of Sudoscan for distal symmetric peripheral neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozaki R, Cheung KK, Wu E, Kong A, Yang X, Lau E, Brunswick P, Calvet JH, Deslypere JP, Chan JC. A new tool to detect kidney disease in Chinese type 2 diabetes patients: comparison of EZSCAN with standard screening methods. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13:937–943. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Smith SC, Xu J, Divers J. Relationships between electrochemical skin conductance and kidney disease in Type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowden DW, Rudock M, Ziegler J, Lehtinen AB, Xu J, Wagenknecht LE, Herrington D, Rich SS, Freedman BI, Carr JJ, Langefeld CD. Coincident Linkage of Type 2 Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Measures of Cardiovascular Disease in a Genome Scan of the Diabetes Heart Study. Diabetes. 2006;55:1985–1994. doi: 10.2337/db06-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman BI, Hsu FC, Langefeld CD, Rich SS, Herrington DM, Carr JJ, Xu J, Bowden DW, Wagenknecht LE. The impact of ethnicity and sex on subclinical cardiovascular disease: the Diabetes Heart Study. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2511–2518. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van LF, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalfallah K, et al. Noninvasive galvanic skin sensor for early diagnosis of sudomotor dysfunction: application to diabetes. IEEE Sensors J. 2010;12:456–463. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Box GEP, Cox DR. An analysis of tranformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1964;26:211–246. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coffin M, Sukhatme S. Receiver operating characteristic studies and measurement errors. Biometrics. 1997;53:823–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF. The inconsistency of “optimal” cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:670–675. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rota M, Antolini L, Valsecchi MG. Optimal cut-point definition in biomarkers: the case of censored failure time outcome. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:24. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0009-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvet JH, Dupin J, Winiecki H, Schwarz PE. Assessment of small fiber neuropathy through a quick, simple and non invasive method in a German diabetes outpatient clinic. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121:80–83. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gin H, Baudoin R, Raffaitin CH, Rigalleau V, Gonzalez C. Non-invasive and quantitative assessment of sudomotor function for peripheral diabetic neuropathy evaluation. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.