Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pro-coagulant full length Tissue Factor (flTF) and its minimally coagulant alternatively spliced isoform (asTF), promote breast cancer (BrCa) progression via different mechanisms. We previously showed that flTF and asTF are expressed by BrCa cells, resulting in autoregulation in a cancer milieu. BrCa cells often express hormone receptors such as the estrogen receptor (ER), leading to the formation of hormone-regulated cell populations.

OBJECTIVE

To investigate whether TF isoform-specific and ER-dependent pathways interact in BrCa.

METHODS

TF isoform-regulated gene sets were assessed using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA). Tissues from a cohort of BrCa patients were divided into ER positive and ER negative groups. Associations between TF isoform levels and tumor characteristics were analyzed in these groups. BrCa cells expressing TF isoforms were assessed for proliferation, migration and in vivo growth in the presence or absence of estradiol.

RESULTS

IPA analysis pointed to similarities between ER- and TF-induced gene expression profiles. In BrCa tissue specimens, asTF expression associated with grade and stage in ER positive but not in ER negative tumors. flTF only associated with grade in ER positive tumors. In MCF-7 cells, asTF accelerated proliferation in the presence of estradiol in a β1 integrin-dependent manner. No synergy between asTF and the ER pathway was observed in a migration assay. Estradiol accelerated the growth of asTF-expressing tumors but not control tumors in vivo in an orthotopic setting.

CONCLUSION

TF isoform and estrogen signalling share downstream targets in BrCa; concomitant presence of asTF and estrogen signalling is required to promote BrCa cell proliferation.

Keywords: blood coagulation, integrin beta1, cell movement, cell proliferation, tumors

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BrCa) is the most widespread cancer type among women. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated 508,000 breast cancer-related deaths in 2011, placing BrCa in the group of solid cancer forms with the highest mortality rates. Seventy percent of all BrCa tumors are estrogen receptor (ER) positive [1, 2]. ER exists in two isoforms, ERα and ERβ, but the effects of estrogen are mainly regulated by the former. Interestingly, ERα's expression levels are higher in the tumor compartment compared to healthy tissue [3]. ER resides in the cytoplasm in complex with HSP90. Upon estradiol (E2) binding, HSP90 dissociates from the complex and ER dimers translocate to the nucleus where ER binds to Estrogen Responsive Elements (EREs) located in the promoter regions of target genes [4, 5]. E2-ER-DNA interaction leads to the recruitment of co-activators with histone acetyl transferase (HAT) activity, resulting in chromatin opening and increased gene transcription [6]. Target gene expression plays a major role in proliferation, survival (cyclins D,A,E) [7] and metastasis (MMP2) [8] which are crucial processes in cancer progression [9]. Therefore, anti-cancer treatment based on inhibition of ER signalling is a commonly used strategy. BrCa patients with ERα positivity receive treatments either to block the receptor, or to downregulate estrogen levels, which prolongs recurrence-free survival [10].

Full Length Tissue Factor (flTF) is a 47 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that initiates blood coagulation [11]. In addition to its clotting function, flTF binding to its ligand, coagulation factor VII/VIIa (FVIIa), leads to the activation of a subset of G-protein coupled receptors termed Protease Activated Receptors (PARs) [12]. In murine models, flTF signalling via PARs is an important contributor to BrCa progression [13], and higher flTF expression levels in tumors associates with poor prognosis [14, 15].

TF pre-mRNA can undergo alternative splicing, yielding a soluble protein termed alternatively spliced tissue factor (asTF) [16]. Although asTF is detected in human thrombi and can, at high concentrations, shorten clotting times in the presence of negatively charged phospholipids [16], some groups failed to detect asTF procoagulant activity [17, 18]. There is compelling evidence that asTF promotes cancer progression in ways that do not require proteolysis. asTF does not seem to signal via PARs [19]; rather, it facilitates cancer progression via integrin ligation. MiaPaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells [20] and MCF-7 BrCa cells engineered to synthesize asTF [21] gain a proliferative advantage due to asTF expression, leading to the formation of larger and more vascularized tumors. In contrast, flTF expression did not impact proliferation of MCF-7 cells and, somewhat surprisingly, it severely suppressed in vivo growth of MiaPaCa-2 cells, the reasons for which were not determined [20]. In addition, asTF has pro-angiogenic capacity: it ligates αvβ3 integrin resulting in endothelial cell migration, and α6β1 resulting in capillary formation [19]. Integrin ligation was also shown to be crucial for BrCa cell proliferation, revealing that asTF-integrin signalling is a novel key player in BrCa progression [21].

Contributions of ER and asTF/flTF signalling to BrCa progression render both pathways an attractive therapeutic target. Moreover, blocking both pathways simultaneously may lead to a more pronounced tumor regression. We deemed it of importance to evaluate whether the asTF and ER signalling pathways interact with each other, e.g. by sharing downstream signalling components. At present, studies examining potential flTF/asTF and ER synergy are lacking. Using bioinformatics and a large set of BrCa tumor specimens, we investigated whether TF isoforms and ER pathways are likely to interact. We further confirmed the identified potential associations using a panel of in vitro and in vivo assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ingenuity pathway analysis

flTF and asTF dependent gene expression profiles were determined by microarray analysis as described elsewhere [21]. The top 400 upregulated and downregulated genes were uploaded into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis application (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). The gene set was compared with the profiles in the Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base. Associations of asTF, flTF-dependent gene regulation with disease states, cellular functions, and upstream modulators were determined. Fisher's exact test was used to calculate p values.

Tissue microarray analysis

The use of a tissue microarray was approved by the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) medical ethics committee. Non-metastasized BrCa samples from 574 patients that underwent surgery at LUMC from 1985 to 1994 were used [21, 22]. Subjects’ age, tumor grade, histological type, stage, nodal involvement, PgR, Her2 and ER status were available for analysis. Tissues were stained with flTF and asTF-specific antibodies as detailed before [23, 13]. The percentage of flTF or asTF positive tumor cells was determined and the lowest quartile was deemed negative. Χ2 statistical tests were used to evaluate associations between flTF / asTF expression and histopathological characteristics in ER+ and ER− tumors.

Cell culture and viral transductions

FRT site-positive MCF-7 cells (clone 2A3-3) and 2A3-3 cells stably transfected with flTF cDNA, asTF cDNA, or a control vector were described before [21]. All cells were cultured in DMEM (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2mM L-glutamine and Penicillin/Streptomycin. To deplete estrogens, 2 weeks before the experiment the growth medium was switched to phenol red free DMEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% charcoal-stripped FCS (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 2mM L-glutamine, and Penicillin/Streptomycin. Scrambled and β1 integrin-specific shRNA lentiviral particles were generated using shRNA vectors obtained from the Mission Library (Sigma-Aldrich). Transduced cells were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin.

Proliferation and migration assays

Cellular proliferation rates were determined using MTT assays as described before [21]. In brief, 2×104 cells per well were seeded in 12 well plates and cultured in phenol red free medium containing 10% charcoal stripped FCS. Because of the short half-life of E2, medium was supplemented with 1 nM, 10 nM E2 (Sigma-Aldrich) or ethanol solvent on days 0, 3, and 6. The day after seeding (day 0) and on day 6, cells were incubated with 0.5mg/ml 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in PBS, for 30 min at 37°C. Subsequently, MTT-containing PBS was removed and replaced by isopropanol/0.04 N HCl. The solution was transferred to a 96 well plate and OD562 was determined. Proliferation rates were expressed as percent increase in the signal compared to day 0. In some experiments, cells were cultured in phenol red-containing media in the presence or absence of the ER antagonist ICI-182,780 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO).

Cell migration was assessed using silicone inserts (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany). Cells were seeded to confluence and the following day, cultures were treated with 12.5 μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 hours to prevent proliferation. Silicone inserts were removed and gap closure was assessed at regular time intervals. The gap area was calculated using Image J software, and migration was expressed as percent closure of the area at the start of the assay.

qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Life Technologies) and converted to cDNA using the Super Script II kit (Life Technologies). Expression levels of ERα were determined by real-time PCR, using CCA CCA ACC AGT GCA CCA TT as a forward primer and GGT CTT TTC GTA TCC CAC CTT TC as a reverse primer.

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in 2× sample buffer (Life Technologies, Blieswijk, Netherlands) and samples were denatured at 95°C for 10 min, loaded on 12% polyacrylamide gels (Life Technologies) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked 1 hr at 4°C and probed with primary and corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using Western Lightning (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), and chemiluminescent bands were visualized with X-ray film. Anti-ER antibody was from Cell Signaling (Beverly MA), anti-β-actin was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK) and anti-β1 integrin was from Millipore (Amsterdam, Netherlands)

Orthotopic breast cancer model and immunohistochemistry

Animal experiments were approved by the LUMC animal welfare committee. Orthotopic injections (5 animals per group) were performed as described elsewhere [21]. In brief, 2×106 control (pcDNA) or asTF-expressing cells were injected into inguinal fat pads of NOD-SCID mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA). Simultaneously, estrogen pellets (1.5mg/pellet, Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL, USA) were placed subcutaneously. Tumor dimensions were measured with calipers and tumor volume was derived using the formula tumor volume = (length × width × width)/2. Tumors were excised and fixed in 10% formalin solution O/N followed by embedding into paraffin. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.3% H2O2. Antigen retrieval was performed in EDTA buffer for 10 min at 100°C. Sections were then blocked with 5% Bovine Serum Albumin in PBS and incubated overnight at room temperature with anti-Ki67 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and anti-vWF primary antibodies (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Sections were incubated for 1 hr with Envision (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), visualized using DAB, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

RESULTS

asTF and flTF pathways are strongly homologous to the ER pathway

Our previous work showed that asTF facilitates BrCa expansion [21]. Gene expression analysis using mRNA of control (pcDNA) and asTF-expressing 2A3-3 cells revealed that asTF upregulates the expression of genes affecting proliferation, survival, and invasion; conversely, tumor suppressors and apoptotic genes were downregulated [21].

flTF expression in BrCa cells conferred a moderate proliferative advantage in vitro but did not result in increased tumor expansion in vivo [21]. To gain a better insight into TF's role in BrCa progression, TF's interaction with other pathways, and to enable a side-by-side comparison of the effects exerted by each TF isoform, we used the microarray data set described before [21] to perform Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). To explore the possible interacting signalling networks, we uploaded the top 400 upregulated and downregulated genes into the IPA application. The profile of asTF-expressing cells was consistent with the role of asTF signalling in disease states such as cancer (Table 1), which is in agreement with previous findings [20, 21, 24]. Furthermore, asTF expression associated significantly with neurological disorders, organismal abnormalities, and diseases of the reproductive system. The cellular functions impacted by asTF signalling span proliferation, motility, and cell cycle regulation, which again emphasize that asTF plays a role in tumorigenesis (Table 2). Apart from associations with cancerous diseases, flTF-related disorders included neurological and dermatological disorders (Table 1). Furthermore, flTF-dependent gene expression profiles associated significantly with cell proliferation, survival, morphology, and assembly (Table 2), all processes linked to tumor progression.

Table 1.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis: top disease states significantly associated with asTF- and flTF-triggered pathways.

| pcDNA vs. asTF | p-value |

|---|---|

| cancer | 2,92E-10 |

| neurological disease | 1,44E-08 |

| skeletal/muscular disorders | 1,44E-08 |

| organismal injury and abnormalities | 3,62E-08 |

| reproductive system disease | 3,62E-08 |

| pcDNA vs. flTF | p-value |

|---|---|

| cancer | 6,48E-14 |

| organismal injury and abnormalities | 6,48E-14 |

| reproductive system disease | 6,48E-14 |

| dermatological diseases and conditions | 1,04E-08 |

| neurological disease | 3,80E-08 |

Table 2.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis: top biological processes significantly associated with asTF- and flTF-triggered pathways.

| pcDNA vs. asTF | p-value |

|---|---|

| cellular growth and proliferation | 8,02E-12 |

| cell death and survival | 1,30E-11 |

| cellular movement | 1,93E-11 |

| cellular development | 6,23E-11 |

| cell cycle | 3,14E-07 |

| pcDNA vs. flTF | p-value |

|---|---|

| cellular growth and proliferation | 7,05E-15 |

| cell death and survival | 8,82E-15 |

| cellular movement | 6,68E-10 |

| cell morphology | 8,84E-07 |

| cellular assembly and organization | 8,84E-07 |

To investigate how asTF and flTF signalling is regulated in BrCa cells, we used IPA to carry out an upstream regulator analysis. Interestingly, the asTF-dependent gene expression profile implied strong similarities with ER- and, to a lesser extent, HER2-dependent gene regulation (Supplementary Table 1); we note that ER and HER2 are two major determining factors in BrCa progression. 110 genes showed expression profiles consistent with E2 stimulation, whereas 50 genes are commonly regulated both in asTF and HER-2 dependent signalling. In addition, the asTF pathway also featured common elements of transhydroxytamoxifen treatment, a strong ER antagonist [25].

In contrast to asTF, flTF-dependent gene regulation appeared to be linked to the p53 pathway. Myc expression and progesterone are important contributors to BrCa progression [26]. Both of these pathways showed an effect on flTF signalling. flTF-dependent gene expression also showed similarities with estrogen-induced signalling, but less significantly when compared to asTF-induced signalling (Supplementary Table 2). These results suggest that distinct regulators contribute to TF isoform dependent signalling.

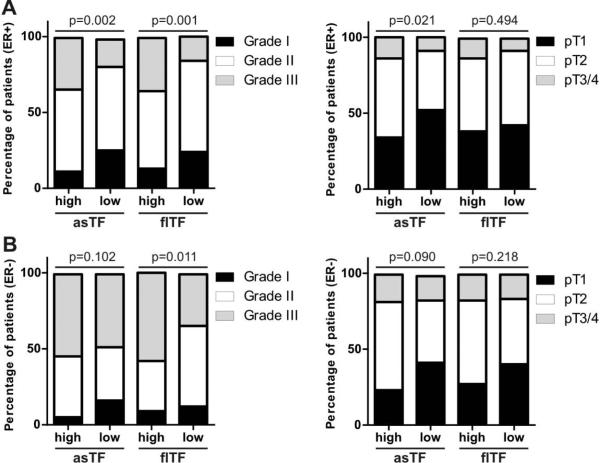

asTF expression associates with BrCa grade and stage in ER+ tumors

The partial overlap between asTF and ER signalling pathways prompted us to investigate this link in BrCa tissue specimens [21, 22]. We previously reported significant associations between asTF expression levels and clinical parameters such as histological grade and tumor stage [21]. Of note, asTF expression did not show association with the ER status [21]. We divided the tumor specimens into ER− and ER+ groups and re-evaluated the associations between asTF expression levels and said clinical parameters. Higher asTF expression positively associated with higher T stage and a more advanced histological grade in ER+ tumors (Fig. 1A,B, supplementary table 3), but not in ER− tumors (Fig. 1C,D, supplementary table 3). There was no association between asTF expression and age, histological type, nodal involvement, and PgR / Her2 status in ER+ and/or ER− specimens (supplementary table 3). Analogous analyses performed for flTF revealed the positive association between flTF expression and grade, both in ER+ and ER− tumor specimens (Fig. 1, supplementary table 4). Interestingly, flTF expression did not associate with stage in ER+ and/or ER− specimens (Fig. 1, supplementary table 4). These findings suggest that asTF, but not flTF, cooperates with the ER signalling pathway to promote BrCa progression.

Fig. 1.

asTF expression positively associates with BrCa grade and stage in patients with ER+, but not ER− tumors. A) Associations of asTF or flTF expression with BrCa grade and stage in patients with ER+ tumors. B) Associations of asTF or flTF expression with BrCa grade and stage in patients with ER+ tumors. The cohort comprised 574 non-metastatic BrCa patients; Χ2 statistical tests were used to evaluate associations. Please see supplementary tables 3 and 4 for the associations between asTF or flTF expression and other clinical parameters.

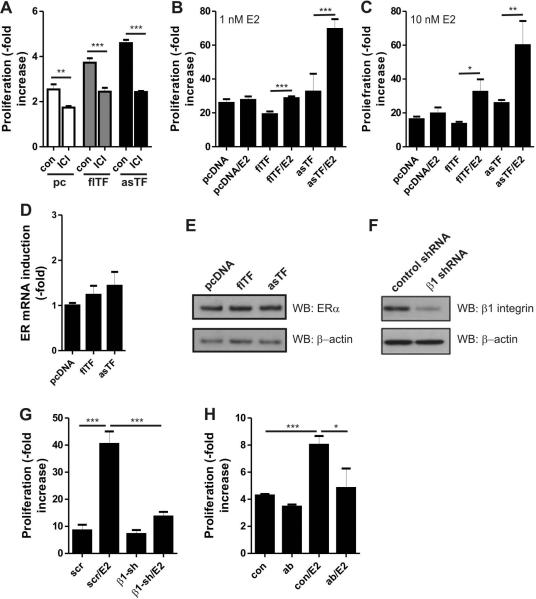

Estradiol increases the proliferation rate of ER+ BrCa cells in a TF-dependent manner

We have previously shown that asTF-expressing cells exhibit higher proliferation rates in phenol red (PR)-containing media [21]. PR is known to act as a weak ER agonist [32]. Indeed, prolonged incubation with the ER antagonist ICI-182,780 reduced proliferation of all our cell lines to a similar extent (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we assessed proliferation rates of control (pcDNA), asTF- and flTF-expressing cells in phenol red-deficient media. asTF- and flTF-expressing cells did not exhibit proliferative advantage over control cells. Interestingly, treatment of these cells with E2 (1nM, 10nM) enhanced growth rates of flTF and asTF-expressing cells (Fig. 2B,C). Importantly, flTF-expressing cells required higher doses of E2 to show maximal proliferation rate compared to asTF-expressing cells, suggesting that asTF and, to a lesser extent, flTF sensitizes cells to E2. This phenomenon was not due to altered expression of ERα, the sole ER isoform in MCF-7 cells [27], as control, flTF- and asTF-expressing cells had very similar expression levels of ERα (Fig. 2D,E).

Fig. 2.

Estrogens and asTF cooperate to induce BrCa cell proliferation. A) Control, flTF- and asTF-expressing cells were cultured in phenol red-containing media in the presence or absence of ER inhibitor ICI-182,780 (final [C] = 100 nM). After 3 days, proliferation rates were determined using MTT assay. B) Control, flTF- and asTF-expressing cells were cultured in phenol red free medium. Cells were treated with either 1 nM E2 or solvent control (EtOH). After 6 days, proliferation rates were determined using MTT assay. C) As in B, but using 10 nM of E2. D) ERα transcript levels in control, flTF-and asTF-expressing cells were determined using real-time PCR. E) ERα protein levels in control, flTF-and asTF-expressing cells were determined by western blotting. F) β1 integrin was downregulated in asTF-expressing cells using lentiviral shRNA. Scrambled shRNA was used as a control. Reduction of β1 integrin protein levels was verified by western blotting. G) Cells were treated with 1 nM E2 or solvent control. Proliferation rates were assessed using MTT assay at days 3 and 6. *P < 0.05, **P <0.01, and ***P < 0.001. H) Proliferation of asTF-expressing cells in the presence or absence of ER and the asTF-blocking antibody Rb1.

Because asTF ligates β1 integrins to promote BrCa proliferation [21], we lowered β1 protein levels in asTF-expressing cells using shRNA (Fig. 2F) and assessed the resultant effects. E2-dependent proliferation was diminished upon β1 downregulation (Fig. 2G), which points to a role for the β1 integrin subset in the observed asTF/E2 synergy. Finally, asTF blockade using our previously characterized asTF-specific monoclonal antibody Rb1 [21] inhibited proliferation in E2 treated cells to a larger extent than that of E2 untreated cells (Fig. 2H). The magnitude of the E2's effect on TF-expressing cells suggests that E2- dependent proliferation is highly dependent on TF function and β1 integrin.

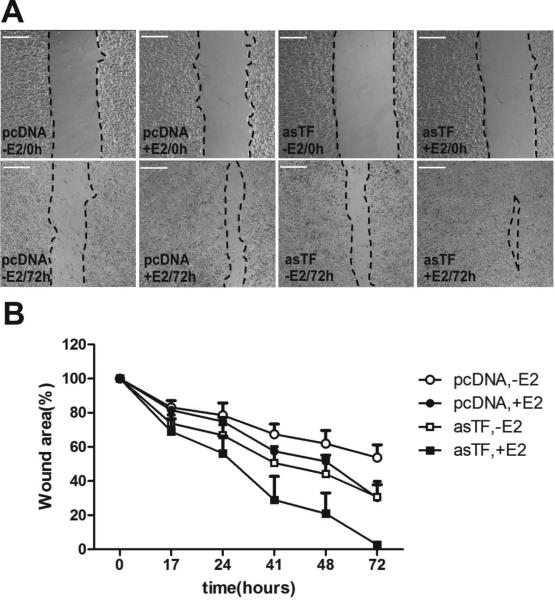

Estrogen and asTF induce migration of BrCa cells

Because asTF is a stronger facilitator of E2-dependent proliferation compared to flTF in our next set of experiments we focused on the asTF isoform. We evaluated the interaction of ER and asTF signaling in BrCa cell migration, a process crucial for metastatic spread. In a modified gap closure assay we observed that, in the absence of E2, asTF-expressing cells migrated faster than pcDNA cells. While the presence of E2 further increased migration rates of pcDNA and asTF cells, we did not observe synergistic effects of asTF expression and E2 stimulation (Fig. 3). These results indicate that, in contrast to cell proliferation, asTF and E2 do not synergize to increase cell migration, yet their effects are additive in potentiating it.

Fig. 3.

E2 and asTF independently promote BrCa cell migration. A) Cells were seeded to confluency in silicone inserts. The following day, inserts were removed to leave a gap (demarcated using a dashed line). Gap closure was monitored at regular time intervals. B) The remaining gap area was calculated as percent closure of the area at t=0 by using Image J software. Scale bars: 300μm.

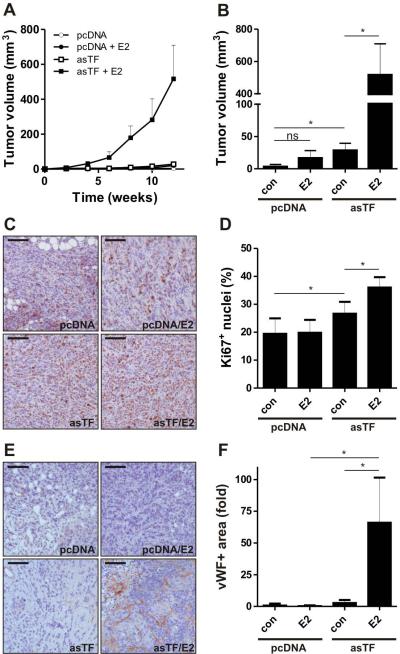

Estrogen increases in vivo tumor growth in BrCa cells expressing asTF

We sought to corroborate the functional significance of the asTF/ER synergy in vivo. As previously reported, asTF-expressing BrCa cells orthotopically injected into mammary fat pads of mice produce larger tumors than control (pcDNA) cells [21]. To assess the impact of estrogens on BrCa cells in vivo, we performed a side-by side comparison of xenografted asTF-expressing and control (pcDNA) cells following subcutaneous placement of estrogen pellets. In line with our previous findings, asTF-expressing cells formed larger tumors compared to control cells [21] and estrogen augmented this effect; remarkably, the volume of tumors formed by control cells did not significantly increase in response to estrogen treatment (Fig. 4A,B). We also evaluated tumor growth rates by Ki67 staining: Ki67 positivity significantly correlated with tumor volume (Fig. 4C,D). Finally, we assessed vascular density in the tumors and observed that the combination of E2 and asTF dramatically increased the levels of vWF-positive structures in tumor tissue (Fig. 4E,F). These findings confirm that estrogen and asTF signalling pathways synergize in BrCa cells in vivo.

Fig. 4.

E2 increases the growth of asTF+ BrCa cells in vivo. A) pcDNA or asTF cells were injected into mammary fat pads of NOD/SCID mice. Estrogen pellets were placed subcutaneously. Tumor growth was monitored for 12 weeks by measuring tumor volume. B) Final tumor volumes are shown. C) Proliferating cells were detected using Ki67 staining. Scale bars: 50μm. D) Ki67+ cells were counted and represented as percent of the total cell number. *P < 0.05, **P <0.01, and ***P < 0.001. E) Vessel structures were detected using anti-vWF antibody F) vWF signal strength is shown as fold increase over control, scale bars: 50μm, *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Here, we analysed the synergy between ER- and TF-triggered pathways in BrCa progression. While flTF- and asTF-dependent pathways converge with ER-dependent pathways, we show that asTF is the main isoform synergizing with the ER pathway in BrCa. We base these conclusions on the following observations: i) asTF expression associated with tumor grade and size only in the specimens of ER+ tumors; ii) BrCa cells expressing asTF responded to estrogen treatment by increasing their proliferative rate; iii) E2 stimulated BrCa cell growth in vivo when asTF is expressed in these cells.

In our previous work, we determined the changes in global gene expression upon asTF and flTF expression in BrCa cells [21]. The obtained gene expression profile was analyzed using IPA and hinted that asTF and flTF expression is associated with diseases such as cancer (Table 1), which is in line with previous findings [20, 21, 28]. TF isoforms also showed significant associations with neurological and reproductive system disorders (Table 1), warranting further studies of possible links between TF isoforms and these diseases. In addition to asTF's role in cell cycle regulation, IPA results suggest that cell death and motility are also controlled by asTF signalling (Table 2). While flTF induced effects on cellular functions overlap with those induced by asTF, flTF appears to selectively influence cellular morphology (Table 2), which is consistent with the literature [29]. asTF-elicited changes in gene expression show high similarity to those elicited by estradiol treatment (Supplementary Table 1). This indicates that the ER and asTF pathways converge downstream. Associations between estrogen and flTF signalling were less significant compared to those between estrogen and asTF (Supplementary Table 2). It is known that TF expression is controlled by oncogenic genes (i.e. K-ras) and impaired p53 expression [30]. Interestingly, flTF-induced gene expression profiles were similar to tumor suppressor p53-dependent expression profiles. This tumor suppressive phenotype may explain why flTF only marginally impacted BrCa cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro [21].

An overlap between the estrogen pathway and the asTF pathway was also evaluated in a large BrCa patient cohort. asTF expression was significantly associated with tumor size and grade in ER+ tumors, yet not in ER− tumors, comprising another line of evidence for a combined effect of these two components on BrCa progression. flTF associated with BrCa stage, but this was not restricted to ER+ tumors. 25% of all BrCa tumors show overexpression of the Her2/neu proto-oncogene, leading to decreased survival rates [31]. Interestingly, IPA analysis pointed towards ERBB2 as a potential modulator of the asTF pathway (Supplementary Table 3). We did not analyse the relationship between these two pathways due to the low number of patients with Her2 overexpression in our cohort (Supplementary table 3).

To further investigate ER and asTF synergy on the cellular level, we performed in vitro proliferation assays. Our previous work showed a proliferative advantage of asTF- and flTF-expressing cells over control cells in vitro [21] which is divergent from the findings in this paper (Fig. 1A-C). In our earlier studies [21], BrCa cells were cultured in medium containing phenol red, a weak ER activator [32]. Because the presence of phenol red may impact the outcome of assays studying the effects of estrogens on cellular behaviour [33], we have now performed proliferation assays using TF isoform-expressing cells maintained in culture media lacking phenol red.

E2 is the main estrogen produced by ovaries during the reproductive period; high levels of E2 are associated with increased BrCa risk [27, 34]. We here show that even a low dose of E2 (1nM) is sufficient to enhance the proliferation rate of asTF-expressing cells, while a 10-fold higher dose of E2 (10nM) is required to enhance proliferation of flTF-expressing cells. These data suggest that asTF expression increases sensitivity to E2. Moreover, both pathways elevate expression of positive regulators of the cell cycle, e.g. CCNA1 (Supplementary Table 1), [21] and decrease expression of negative cell cycle regulators, e.g. p21KIP [21, 35]. In line with our previous findings, E2-induced proliferation of asTF-expressing cells was dependent on β1 integrin ligation (Fig. 2G). Although these data raise the possibility that E2-dependent proliferation is dependent on asTF, we cannot exclude that the opposite, i.e. asTF-dependent proliferation is dependent on E2, is true, especially as treatment with ICI-182,780 reduced proliferation rates of asTF-expressing cells to roughly those of control cells treated with ICI-182,780. Further studies are warranted to ascertain whether ER signaling and asTF contribute independently and equally to BrCa cell proliferation, or whether one is required for the other.

In vivo, E2 increased asTF-dependent growth, but not expansion of pcDNA cells. asTF expression in itself was also sufficient to spur tumor growth, which is in contrast with the results that we obtained in vitro (Fig. 3A,B). We posit that in vivo, asTF-dependent tumor growth in the absence of E2 is likely facilitated by asTF's angiogenic potential (Fig 4E,F) as well as asTF's ability to recruit monocytes and macrophages [21, 23, 24] . Of note, in our previous work we also showed that asTF inhibition using antibody approaches diminished proliferation of the ER- cell line MDA-MB-231-mfp in vitro and in vivo. [21]. Thus, pathways other than those dependent on estrogen likely synergise with asTF, particularly in aggressive ER- BrCa cell lines.

Our studies have uncovered significant associations between the asTF/E2 synergy and clinical parameters. Unfortunately, a number of important BrCa-related issues, such as asTF's associations with disease biology and/or molecular subtypes, remain to be addressed. It would also be most interesting to determine whether asTF expression impacts loco-regional and/or systemic spread, , but our currently available tools preclude us from drawing conclusions on the involvement of asTF in metastasis. Nevertheless, metastasis is critically dependent on the migratory potential of malignant cells and we determined that BrCa cell migration, as assayed in a wound closure assay, is asTF-dependent. Further, we showed in our experimental setup that asTF contributes to BrCa cell migration in a manner independent of E2. One interesting aspect of this study is that control (pcDNA) cells showed enhanced migration, but not proliferation, after stimulation with E2, suggesting that E2-induced migration and proliferation likely rely on distinct pathways. Indeed, binding of E2 to ER results in the activation of Src as well as focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/paxillin complexation. This in turn activates signalling pathways involving Rac, Rho, and PAK-1 that play a critical role in cell migration [36]. In contrast, E2-dependent proliferation is mainly under the control of Src/Shc/ERK pathways that may induce CCNA1 expression and, concomitantly, higher proliferation rates [37]. FAK/Rac-dependent pathways do not appear to require the presence of asTF to elicit migration, whereas asTF is evidently crucial for ERK-controlled proliferation. It needs to be stressed that, aside from cancer cell migration, metastasis is dependent on many different processes. Thus, asTF-potentiated migration does not comprise a direct evidence that asTF promotes metastasis in BrCa; that being said, we recently showed that to be the case in vivo in an orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer [24].

Similarly, it would have been of interest to assess whether asTF status could predict overall- or disease-free survival in BrCa patients as a function of hormonal therapy. Unfortunately, the cohort used to identify associations between asTF and clinical parameters was assembled between 1985 and 1994, when hormonal therapy was not a standard treatment option for patients with ER+ tumors; thus, we were not able to assess patient survival as a function of hormonal therapy. Nevertheless, our study does suggest that targeting asTF, either pharmacologically or by means of blocking antibodies, may enhance the effects of hormonal therapy in ER+ BrCa. In fact, a study shows that integrin β1-dependent signalling results in phosphorylation of ERα [38]. As ERα-dependent gene expression is dependent on estrogen binding, as well as ligand-independent phosphorylation [39], ERα could well be the point at which E2 and asTF-dependent signalling converge. Also, integrin β1 appears to be involved in the development of resistance to tamoxifen; thus, inhibiting asTF – a ligand for β1 integrins – could very well reverse this process.

In conclusion, asTF and ER pathways synergize to facilitate proliferation of BrCa cells. Blocking downstream common elements of these two signalling pathways may thus be a novel and effective approach to stem BrCa progression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a VIDI fellowship (Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, grant nr. 17.106.329) to H. H. Versteeg and NIH/NCI grant 1R21 CA160293 to V. Y. Bogdanov.

Footnotes

ADDENDUM

B. Kocatürk performed the in vitro and in vivo experiments, and wrote the paper. C. Tieken performed in vivo experiments. D. Vreeken and B. Ünlü performed immunohistochemical analysis. C. C. Engels, E. M. de Kruijf and P. J. Kuppen analysed patient data. P. H. Reitsma and V. Y. Bogdanov designed the experiments. H. H. Versteeg designed the experiments, wrote the paper and supervised the project.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

H. H. Versteeg and V. Y. Bogdanov have a patent USPTO appl. # 20130189276 pending. The other authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lumachi F, Brunello A, Maruzzo M, Basso U, Basso SM. Treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:596–604. doi: 10.2174/092986713804999303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masood S. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in cytology: a comprehensive review. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992;8:475–91. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840080508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang B, Omoto Y, Iwase H, Yamashita H, Toyama T, Coombes RC, Filipovic A, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Differential expression of estrogen receptor alpha, beta1, and beta2 in lobular and ductal breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323719111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V, Chambon P. The estrogen receptor binds tightly to its responsive element as a ligand-induced homodimer. Cell. 1988;55:145–56. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratt WB. The hsp90-based chaperone system: involvement in signal transduction from a variety of hormone and growth factor receptors. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:420–34. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann M, Cortez V, Vadlamudi RK. Epigenetics of estrogen receptor signaling: role in hormonal cancer progression and therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:1691–707. doi: 10.3390/cancers3021691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musgrove EA, Caldon CE, Barraclough J, Stone A, Sutherland RL. Cyclin D as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:558–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin L, Liao L, Redmond A, Young L, Yuan Y, Chen H, O'Malley BW, Xu J. The AIB1 oncogene promotes breast cancer metastasis by activation of PEA3-mediated matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5937–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00579-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renoir JM, Marsaud V, Lazennec G. Estrogen receptor signaling as a target for novel breast cancer therapeutics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:449–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leary A, Dowsett M. Combination therapy with aromatase inhibitors: the next era of breast cancer treatment? Br J Cancer. 2006;95:661–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monroe DM, Hoffman M. What does it take to make the perfect clot? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:41–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000193624.28251.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camerer E, Huang W, Coughlin SR. Tissue factor- and factor X-dependent activation of protease- activated receptor 2 by factor VIIa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5255–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Versteeg HH, Schaffner F, Kerver M, Petersen HH, Ahamed J, Felding-Habermann B, Takada Y, Mueller BM, Ruf W. Inhibition of tissue factor signaling suppresses tumor growth. Blood. 2008;111:190–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maciel EO, Carvalhal GF, da Silva VD, Batista EL, Jr., Garicochea B. Increased tissue factor expression and poor nephroblastoma prognosis. J Urol. 2009;182:1594–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueno T, Toi M, Koike M, Nakamura S, Tominaga T. Tissue factor expression in breast cancer tissues: its correlation with prognosis and plasma concentration. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:164–70. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogdanov VY, Balasubramanian V, Hathcock J, Vele O, Lieb M, Nemerson Y. Alternatively spliced human tissue factor: a circulating, soluble, thrombogenic protein. Nat Med. 2003;9:458–62. doi: 10.1038/nm841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boing AN, Hau CM, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Human alternatively spliced tissue factor is not secreted and does not trigger coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1423–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Censarek P, Bobbe A, Grandoch M, Schror K, Weber AA. Alternatively spliced human tissue factor (asHTF) is not pro-coagulant. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van den Berg YW, van den Hengel LG, Myers HR, Ayachi O, Jordanova E, Ruf W, Spek CA, Reitsma PH, Bogdanov VY, Versteeg HH. Alternatively spliced tissue factor induces angiogenesis through integrin ligation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19497–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905325106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hobbs JE, Zakarija A, Cundiff DL, Doll JA, Hymen E, Cornwell M, Crawford SE, Liu N, Signaevsky M, Soff GA. Alternatively spliced human tissue factor promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a pancreatic cancer tumor model. Thromb Res. 2007;120(Suppl 2):S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(07)70126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kocaturk B, Van den Berg YW, Tieken C, Mieog JS, de Kruijf EM, Engels CC, van der Ent MA, Kuppen PJ, Van de Velde CJ, Ruf W, Reitsma PH, Osanto S, Liefers GJ, Bogdanov VY, Versteeg HH. Alternatively spliced tissue factor promotes breast cancer growth in a beta1 integrin-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:11517–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Nes JG, de Kruijf EM, Faratian D, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Falconer C, Smit VT, Kay C, van de Vijver MJ, Kuppen PJ, Bartlett JM. COX2 expression in prognosis and in prediction to endocrine therapy in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Feb;125(3):671–85. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivasan R, Ozhegov E, Van den Berg YW, Aronow BJ, Franco RS, Palascak MB, Fallon JT, Ruf W, Versteeg HH, Bogdanov VY. Splice variants of tissue factor promote monocyte-endothelial interactions by triggering the expression of cell adhesion molecules via integrin-mediated signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2087–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unruh D, Turner K, Srinivasan R, Kocatürk B, Qi X, Chu Z, Aronow BJ, Plas DR, Gallo CA, Kalthoff H, Kirchhofer D, Ruf W, Ahmad SA, Lucas FV, Versteeg HH, Bogdanov VY. Alternatively spliced tissue factor contributes to tumor spread and activation of coagulation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2014 Jan;134(1):9–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katzenellenbogen BS, Norman MJ, Eckert RL, Peltz SW, Mangel WF. Bioactivities, estrogen receptor interactions, and plasminogen activator-inducing activities of tamoxifen and hydroxy tamoxifen isomers in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1984;44:112–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Chen Y, Olopade OI. MYC and Breast Cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:629–40. doi: 10.1177/1947601910378691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Key T, Appleby P, Barnes I, Reeves G. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:606–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van den Berg YW, Osanto S, Reitsma PH, Versteeg HH. The relationship between tissue factor and cancer progression: insights from bench and bedside. Blood. 2012;119:924–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-317685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carson SD, Pirruccello SJ. Tissue factor and cell morphology variations in cell lines subcloned from U87-MG. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1998;9:539–47. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu JL, May L, Lhotak V, Shahrzad S, Shirasawa S, Weitz JI, Coomber BL, Mackman N, Rak JW. Oncogenic events regulate tissue factor expression in colorectal cancer cells: implications for tumor progression and angiogenesis. Blood. 2005;105:1734–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choudhury A, Kiessling R. Her-2/neu as a paradigm of a tumor-specific target for therapy. Breast Dis. 2004;20:25–31. doi: 10.3233/bd-2004-20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katzenellenbogen BS, Kendra KL, Norman MJ, Berthois Y. Proliferation, hormonal responsiveness, and estrogen receptor content of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells grown in the short-term and long-term absence of estrogens. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4355–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berthois Y, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Phenol red in tissue culture media is a weak estrogen: implications concerning the study of estrogen-responsive cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2496–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyytinen H, Pukkala E, Ylikorkala O. Breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women using estrogen- only therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1354–60. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000241091.86268.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao XH, Lu DL, Wang N, Liu LY, Wang Y, Li YQ, Yan TB, Sun XG, Hu P, Zhang TC. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates proliferation of breast cancer MCF-7 cells via a p21/PCNA/E2F1-dependent pathway. FEBS J. 2014;281:927–42. doi: 10.1111/febs.12658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Wang JP, Santen RJ, Kim TH, Park H, Fan P, Yue W. Estrogen stimulation of cell migration involves multiple signaling pathway interactions. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5146–56. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alvaro D, Onori P, Metalli VD, Svegliati-Baroni G, Folli F, Franchitto A, Alpini G, Mancino MG, Attili AF, Gaudio E. Intracellular pathways mediating estrogen-induced cholangiocyte proliferation in the rat. Hepatology. 2002;36:297–304. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pontiggia O, Sampayo R, Raffo D, Motter A, Xu R, Bissell MJ, Joffe EB, Simian M. The tumor microenvironment modulates tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer: a role for soluble stromal factors and fibronectin through beta1 integrin. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:459–71. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1766-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lannigan DA. Estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Steroids. 2003;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.