Abstract

The widest scan that had been demonstrated previously for rapid scan EPR was a 155 G sinusoidal scan. As the scan width increases, the voltage requirement across the resonating capacitor and scan coils increases dramatically and the background signal induced by the rapidly changing field increases. An alternate approach is needed to achieve wider scans. A field-stepped direct detection EPR method that is based on rapid-scan technology is now reported, and scan widths up to 6200 G have been demonstrated. A linear scan frequency of 5.12 kHz was generated with the scan driver described previously. The field was stepped at intervals of 0.01 to 1 G, depending on the linewidths in the spectra. At each field data for triangular scans with widths up to 11.5 G were acquired. Data from the triangular scans were combined by matching DC offsets for overlapping regions of successive scans. This approach has the following advantages relative to CW, several of which are similar to the advantages of rapid scan. (i) In CW if the modulation amplitude is too large, the signal is broadened. In direct detection field modulation is not used. (ii) In CW the small modulation amplitude detects only a small fraction of the signal amplitude. In direct detection each scan detects a larger fraction of the signal, which improves the signal-to-noise ratio. (iii) If the scan rate is fast enough to cause rapid scan oscillations, the slow scan spectrum can be recovered by deconvolution after the combination of segments. (iv) The data are acquired with quadrature detection, which permits phase correction in the post processing. (v) In the direct detection method the signal typically is oversampled in the field direction. The number of points to be averaged, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio, is determined in post processing based on the desired field resolution. A degased lithium phthalocyanine sample was used to demonstrate that the linear deconvolution procedure can be employed with field-stepped direct detection EPR signals. Field-stepped direct detection EPR spectra were obtained for Cu2+ doped in Ni(diethyldithiocarbamate)2, Cu2+ doped in Zn tetratolylporphyrin, perdeuterated tempone in sucrose octaacetate, vanadyl ion doped in a parasubstituted Zn tetratolylporphyrin, Mn2+ impurity in CaO, and an oriented crystal of Mn2+ doped in Mg(acetylacetonate)2(H2O)2.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

In rapid-scan electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) the magnetic field is scanned through resonance in a time that is short relative to the electron spin relaxation times [1–3]. The directly detected quadrature signal is obtained using a double-balanced mixer with the reference at the resonance frequency. Deconvolution of the rapid-scan signal gives the absorption spectrum [4, 5]. By contrast conventional continuous wave (CW) EPR uses phase sensitive detection at the modulation frequency. For a wide range of samples, rapid scan gives improved signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) relative to CW spectra [1]. The widest scan that we have previously demonstrated for rapid scan EPR was a 155 G sinusoidal scan [6]. As the scan width increases, the voltage requirement across the resonating capacitor and scan coils increases dramatically and the background signal induced by the rapidly changing field increases. An alternate approach is needed to achieve wider scans. We have now developed field-stepped direct detection EPR, which is based on the rapid scan technology, to generate much wider scans. To test the performance of the method, samples were examined with a variety of linewidths and lineshapes. The narrowest linewidth (ΔBpp = 22 mG) was for degassed lithium phthalocyanine (LiPc), which exhibited rapid-scan oscillations in the signal and required deconvolution to obtain the slow-scan absorption spectrum. Samples with resolved g- and A anisotropy include Cu2+ doped in Ni(diethyldithiocarbamate)2 (Ni(Et2dtc)2), Cu 2+ doped in Zn tetratolylporphyrin (ZnTTP), perdeuterated 4-oxo-2,2,6,6-tetra-methylpiperidinyl-N-oxyl (PDT) in sucrose octaacetate, vanadyl ion doped in Zn p-COOH-tetratolylporphyrin (ZnTTP-COOH), and Mn2+ impurity in CaO. The spectrum of a crystal of Mn2+ doped in Mg(acetylacetonate)2(H2O)2 (Mg(acac)2(H2O)2) has well-resolved hyperfine lines and low-intensity forbidden transitions over a sweep width of 6200 G.

2. Approach

To encompass a wide spectrum, multiple triangular scans were acquired with extensive overlap of the field ranges (Fig. 1). In the following description, specific values are given to facilitate understanding, but there is substantial flexibility in choice of parameters. For example to encompass a 150 G scan, 151 scans with widths of 11.5 G were recorded with 1 G offsets between the centers of the scans. Since linearity of a triangular scan is better in the center than at the extremes of the scan, only the central 80% segments of the scans were selected for inclusion in the combined data set. Thus for the example of 11.5 G scans, the central 9.2 G segments were used. The 1 G offset between centers of scans gives an 8.2 G region of overlap of each scan with the previous and following scans. The information from the up- and down-scans and from multiple cycles of the triangular scans is combined. In the direct-detected spectra the y axis values are relative to a DC offset that is different for each scan. To combine successive scans the offset was calculated as the difference between the means of the y-axis values in the overlapping 8.2 G regions. The large spectral overlaps provide accurate determination of the offsets. This offset correction was applied before averaging values from successive scans and combining into the spectral array. Since the scan rate of a triangular scan is constant across the spectrum, linear deconvolution can then be applied to obtain the slow-scan absorption spectrum.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of post processing procedure for spectral reconstruction in field-stepped direct detection, using typical parameters. For example, data could be acquired at 151 field positions in 1.0 G increments over 150 G. Each scan is 11.5 G wide and the linear scan frequency is 5.12 kHz, which corresponds to a scan rate of 118 kG/s. From each of the scans the central 80 % is selected. The DC offset between scans is calculated by comparing signal intensity at the comparable fields in overlapping segments of successive scans and this correction is applied prior to combining the spectra.

3. Methods

3.1 Samples

LiPc prepared electrochemically was provided by Prof. Swartz, Dartmouth College [7, 8]. A small crystal was placed in a capillary tube. The tube was extensively evacuated and then flame sealed. The capillary tube containing LiPc was placed in a 4 mm outer diameter quartz tube beside a second capillary tube filled with water to a height of 1 cm to lower the Q of the resonator to about 1000. The bandwidth of the rapid scan signal for this sample is so large that a lowered Q is required to decrease broadening of the signal.

The preparation of Cu2+ doped in Ni(Et2dtc)2 was described in [9]. The preparation of Cu2+ doped in ZnTTP and of VO2+ doped in ZnTTP-COOH were described in [10]. The sample of nitroxide PDT in sucrose octaacetate was prepared as previously reported [11]. Calcium oxide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (part number 248568, St. Louis, MO). Mn2+ is an impurity in the reagent CaO powder. The sample was handled under nitrogen gas and placed in a 4 mm outer diameter quartz tube. The tube was evacuated on a high vacuum system for about 6 hr, then flame sealed. Mg(acac)2(H2O)2 was prepared and characterized as described in [12, 13]. The crystal doped with Mn2+ was grown from acetonitrile. Sample heights were 6–7 mm, to ensure uniform B1 and scan field along the full lengths of the samples.

3.2. EPR spectroscopy

A Bruker E500T spectrometer was used to record CW and field-stepped direct detection spectra with a Bruker Flexline ER4118X-MD5 dielectric resonator, which can excite spins over a sample height of about 1 cm. The Q of the resonator is ~9000 for nonlossy samples [2]. A Bruker SpecJet II fast digitizer was used. The 10 ns timebase was selected for LiPc and for Mn2+ in Mg(acac)2(H2O)2 and the 40 ns timebase was used for the other samples. The phase difference between the quadrature detection channels was calibrated with a small sample of solid BDPA (1:1 α,γ-bisdiphenylene-β-phenylallyl: benzene) radical [14]. The deviation between the Kronig-Kramers transformation of the absorption signal and the observed dispersion signal showed that a phase correction of 7° was required. The amplitude difference between quadrature detection channels was calibrated with a small degassed sample of solid LiPc. There was a 7% amplitude difference between the I and Q channels. The corrections were applied in the post-processing of the field-stepped direct detection signals.

The linear scans were generated with the previously described scan driver [15]. The scan coils were constructed from 60 turns of Litz wire (255 strands of AWG44 wire). The coils have about 8 cm average diameter, were placed about 4 cm apart, and have a coil constant of 17.3 G/A. Mounting the coils on the magnet, rather than on the resonator, reduces the oscillatory background signal induced by the rapid scans [6]. The placement of highly conducting aluminum plates on the poles of the Bruker 10″ magnet reduces resistive losses in the magnet pole faces that arise from induced currents [1]. The dielectric resonator decreases eddy currents induced by the rapidly-changing magnetic fields relative to resonators with larger amounts of metal. The scan frequency of 5.12 kHz was selected because the background signal induced by the rapidly varying field is relatively small at this scan frequency. Since the linearity is high over more than 90% of the scan at 5.12 kHz, the use of only the central 80% is conservative. Data were acquired in blocks of 3 cycles at each field step. For the spectra used in this study, the scan rate is 118 kG/s, which is 2×fs×Bm G/s where fs is the scan frequency and Bm is the scan width.

The incident powers were converted to B1 using the known resonator efficiency of 3.8 G/W1/2 at Q of 9000 and the dependence of efficiency on √Q when Q is decreased [16]. The power selection was relatively conservative to prevent distortion of the lineshape by power saturation at higher B1. The modulation frequency for the CW spectra of LiPc was 10 kHz and the modulation frequencies for other samples were 100 kHz. The modulation amplitudes were selected to be about 20% of ΔBpp for the narrowest feature in each spectrum. These parameters result in less than 2% line broadening relative to spectra obtained at lower modulation amplitude and smaller B1. The large numbers of points acquired in the field axis of the field-stepped spectra were decreased by averaging about 100 points, to improve S/N and have a field resolution comparable to the CW spectra. First-derivatives of the field-stepped direct detection spectra were obtained by numerical differentiation followed by a Gaussian filter selected to give less than 5% broadening. The same Gaussian filter was applied to the CW spectra.

For CW spectra the acquisition time is the conversion time per point multiplied by the number of field steps and the number of scans, which is approximately equal to the elapsed time because there is little overhead in the software. For field-stepped direct detection, the calculated acquisition time is 1/fs multiplied by the product of number of scan cycles combined in the software, the number of scans averaged and the number of field steps. The lapsed time is longer than the calculated time because of overhead in the software. For Cu2+ in Ni(Et2dtc)2, Cu2+ in ZnTTP, PDT in sucrose octaacetate, VO2+ in Zn(TTP-COOH) and Mn2+ in CaO, the data acquisition times were 15 min for both CW and field-stepped direct detection.

4. Results

Spectra showing the application of the field-stepped method for LiPc are shown in Fig. 2. The CW spectrum of degassed LiPc has a peak-to-peak linewidth of 22 mG and therefore provides a stringent test of the field-stepped approach with respect to lineshape fidelity and the deconvolution of rapid scan effects. High resolution of the field axis for the final spectrum is needed, so data were acquired at 201 center fields with 0.01 G increments. For the LiPc sample, the 11.5 G scans were much wider than required to construct the final 2.0 G spectrum, but the wider scans were selected to push the experiment into the rapid scan regime, and thereby test the effectiveness of the linear deconvolution procedure for the combined data [4]. A 5.12 kHz scan frequency with 10 ns sampling in the Specjet II digitizer permits acquisition of three full cycles of the triangular scan within the available 64k memory. This results in 9766 points per half cycle which corresponds to 1.2 mG/point. When spectra are combined, the selection of corresponding fields for which y-axis values should be average is limited by the field resolution of the initial data. To obtain adequate definition of the rapid scan oscillations [4, 17], the initial data were linearly interpolated by a factor of 10, to give 0.12 mG/point resolution. If the oscillations are not well defined and accurately combined, the signal in the deconvolved spectrum is broadened. Interpolation was not needed for samples discussed below in which rapid scan oscillations were not observed. Plots of the central 80% of the 1st, 101st, and 201st scans are shown in Fig. 2A. After the offsets of the central field are taken into account, the spectra aligned as shown in Fig. 2B. The combination of all 201 scans results in the spectrum shown in Fig. 2C. The absorption spectrum after linear deconvolution of the rapid scan effects [4] is shown in Fig. 2D and Fig. 3A. The first derivative of the spectrum in Fig. 3A, obtained by numerical differentiation (Fig. 3B) is in good agreement with the CW spectrum. The agreement between the CW lineshape and the lineshape obtained by deconvolution of a single scan is substantially better than with the lineshape obtained by combining multiple scans. The slight broadening (about 3 mG) of the field-stepped spectrum is attributed to field instabilities or trigger jitter in the digitizer.

Figure 2.

Example of the spectral reconstruction procedure for LiPc. A) Spectrum numbers 1, 101, and 201 from the set of 201 spectral steps, showing the central 80%. B) Alignment of these three scans after shifting in time to correct for the stepping of the field. C) LiPc spectra obtained by combining contributions from all 201 spectra, after correction for DC offset. For the LiPc spectra rapid scan oscillations were observed in the signal. D) The slow-scan absorption spectrum was reconstructed by deconvolution.

Figure 3.

A) Spectrum of LiPc obtained by field-stepped direct detection. B) The first derivative of the spectrum in part A (black, solid) overlaid on the CW spectrum (red, dashed) obtained with a modulation amplitude of 3.6 mG and 2 mG field resolution. The B1 was 3.3 mG for both spectra.

EPR spectra of immobilized type 1 Cu2+ complexes such as Cu2+ in Ni(Et2dtc)2 exhibit well-resolved g- and A-anisotropy and test the accuracy of the methodology for lineshapes that are broader than individual segments (Fig. 4). The field-stepped spectrum was obtained with 701 steps over 700 G (Fig. 4A). Five of these segments for a small region of the spectrum are shown in Fig. 4D. Although data are acquired with a time axis, the data in Fig. 4B–4D are plotted with an x axis in magnetic field units that takes account of the increments in magnetic field for successive segments. Since the DC offset for each segment is arbitrary, the amplitude of the EPR signal at the same magnetic field position is different for each segment. The DC offset correction was calculated as the difference between the means of the y-axis values in the overlapping 8.2 G regions. After correction for the DC offset, the excellent superposition of segments in overlapping regions is shown in Fig. 4C. Averaging of the contributions from all segments that contribute to this region of the spectrum produces the result that is shown in Fig. 4B.

Figure 4.

Example of the DC offset correction. A) Spectrum of Cu2+ in Ni(Et2dtc)2 obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 701 steps over 700 G. The region that is expanded in parts B – D is marked with a box. B) Expansion of region between 3374.4 and 3387.6 G, obtained by averaging the segments that contribute in the region, after DC offset correction. C) Superposition of 5 successive segments that contribute to the spectrum between 3374.4 and 3387.6 G, after correction for DC offset. Each segment is shown in a different color. D) Five successive segments that contribute to the spectrum between 3374.4 and 3387.6 G, before correction for DC offset. The vertical lines denote the beginning and end of a particular segment. The y axis scales are the same for parts B to D.

The rapidly-changing magnetic field induces a rapid-scan background signal [1]. For 11.5 G segments acquired with a scan frequency of 5.12 kHz and B1 of 17.4 mG as was used to acquire the signals for most of the spectra in this report, the background signal is very small. The background signal increases with B1. To demonstrate the potential impact of the rapid-scan background and DC offset correction, segments acquired with B1 of 174 mG for an empty EPR tube are shown in Fig. 5. Although prior studies have demonstrated that the background signal is dependent on the external magnetic field, the change between nearby segments is small (Fig. 5A). The amplitude of the DC component of the EPR signal, caused by RF reflected from the resonator is typically quite large compared to the detected EPR signal. The spectrometer has a low-pass filter to eliminate the high DC level of the recorded signal without impacting the EPR signal. Therefore, it is necessary to restore the relative DC level in each segment before combining them to obtain the complete spectrum. If no DC correction is applied, summation of the segments causes discontinuities at the beginning of each segment (Fig. 5B). Imperfections in the DC offset correction can leave residual discontinuities, which could potentially be removed by Fourier transformation and filtering to remove the frequencies that correspond to the reciprocal of the step interval [18]. However, this procedure risks deletion of spectral components at this frequency. When the DC offset correction is applied before the segments are averaged, there are no discontinuities at the segment boundaries (Fig. 5C). The resulting baseline signal is a slowly varying monotonic function that is similar to the baseline functions that are commonly observed in CW spectra. Subtraction of a linear fit function for this spectral range removes essentially all of the baseline (Fig. 5D). A more complicated polynomial fit might be needed for a wider scan. The baseline shown in Fig. 5C is for the absorption spectrum, and is barely noticeable after taking the first derivative.

Figure 5.

Rapid scan background signals and DC offset correction for data acquired with a scan frequency of 5.12 kHz and B1 = 174 mG. A) Sampling of 8 of the 22 segments that contribute in the region 3410 to 3441 G for an empty EPR tube. B) Signal obtained by summing all 22 segments without DC offset correction. C) Signal obtained by summing the 22 segments after DC offset correction. D) Signal obtained by subtraction of a linear fit to the data in part C.

The field-stepped direct detected spectrum of Cu2+ in Ni(Et2dtc)2 (Fig 4a) is compared with CW spectra of the same sample in Fig. 6. The spectra in Fig. 6 agree well with previously reported spectra for the same sample [9]. In the region around 3430 G the resolution of the first derivative signal obtained by differentiation of the field-stepped spectrum (Fig. 6B) is slightly better than that for the CW spectrum (Fig. 6C) which is attributed to the large number of data points per gauss used in the stepped-field spectrum.

Figure 6.

A) Spectrum of Cu2+ in Ni(Et2dtc)2 obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 701 steps over 700 G. Each scan was 11.5 G wide and the linear scan frequency was 5.12 kHz, which corresponds to a scan rate of 118 kG/s. B) The first derivative of the spectrum in part A, and C) the CW spectrum obtained with a modulation amplitude of 1.5 G with 0.5 G field resolution. The B1 was 17.4 mG for both spectra.

Spectra of Cu2+ in Zn(TTP) (Fig. 7) exhibit extensive nitrogen hyperfine splitting in the perpendicular region [10]. The field-stepped direct detection spectrum was obtained with 1201 steps over 1200 G (Fig. 7A). The first derivative of the field-stepped absorption spectrum (Fig. 7B) has well-resolved nitrogen hyperfine splitting that matches well with the CW spectrum (Fig. 7C). For the same data acquisition time the S/N in the field-stepped spectrum is better than that for the CW spectrum, which provides substantially better definition of nitrogen hyperfine splitting in the parallel region of the spectrum (Fig 7 B, C insets).

Figure 7.

A) Spectrum of Cu2+ in ZnTTP obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 1201 steps over 1200 G. Each scan was 11.5 G wide and the linear scan frequency was 5.12 kHz, which corresponds to a scan rate of 118 kG/s. B) The first derivative of spectrum in part A, and C) the CW spectrum obtained with a modulation amplitude of 1.2 G with 0.5 G field resolution. The insets below traces B and C show the parallel regions of the spectra with the y axis scale expanded by a factor of 10. The B1 was 17.4 mG for both field-stepped and CW spectra.

Nitroxide radicals are widely used as probes in biophysical studies. Spectra of PDT immobilized in sucrose octaacetate are shown in Fig. 8. The field-stepped direct detection spectrum was obtained with 151 field steps over 150 G (Fig. 8A). The numerical derivative of the field-stepped spectrum (Fig. 8B) is in good agreement with the CW spectrum (Fig. 8C). The resolution of features in the vicinity of 3430 G matches well with previously reported spectra for the same sample [11]. This spectral width is small enough that it has been recorded previously in a sinusoidal rapid scan experiment in which the rapid scan encompassed the full spectral width [6]. The acquisition of accurate lineshapes for this sample by field-stepped direct detection is a further example of the performance for features that are relatively broad compared with the width of the triangular scans.

Figure 8.

A) Spectrum of nitroxide PDT in sucrose octaacetate obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 151 steps over 150 G. Each scan was 11.5 G wide and the linear scan frequency was 5.12 kHz, which corresponds to a scan rate of 118 kG/s. B) The first derivative of the spectrum in part A, and C) CW spectrum obtained with a modulation amplitude of 0.6 G and 0.1 G field resolution. The B1 was 17.4 mG for both spectra.

Spectra of VO2+ porphyrins have well-defined features for the hyperfine splitting along both the parallel and perpendicular axes [19]. The field-stepped direct detection spectrum was obtained with 1501 steps over 1500 G (Fig. 9A). The first derivative of the field-stepped spectrum (Fig. 9C) matches well with the CW spectrum (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

A) Spectrum of VO2+ in Zn(TTP-COOH) obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 1501 steps over 1500 G. Each scan was 11.5 G wide and the linear scan frequency was 5.12 kHz, which corresponds to a scan rate of 118 kG/s. B) The first derivative of spectrum in part A, and C) the CW spectrum obtained with a modulation amplitude of 1.1 G with 0.5 G field resolution. The B1 was 17.4 mG for both spectra.

EPR spectra of Mn2+ are strongly dependent on the symmetry of the local environment and its impact on the zero-field splitting. Spectra of the Mn2+ impurity in CaO are shown in Fig. 10. Because this environment is close to octahedral, the zero field splitting is small and the powder spectrum consists of six lines due to nuclear hyperfine splitting. The field-stepped direct detection spectrum was obtained with 1201 steps over 600 G (Fig. 10A). The 0.5 G field increments were selected to give good definition of the six manganese hyperfine lines, which have 0.7 G peak-to-peak linewidths. A broad underlying signal with g ~ 2 is more clearly defined in the absorption spectrum than in the first derivative spectra (Fig. 10B, 10C). The first derivative of the field-stepped spectrum is in good agreement with the CW spectrum. The integral of the CW spectrum also shows the broad underlying feature. The difference between the first derivative and absorption spectra is a reminder of the extent to which the first-derivative display tends to emphasize sharp features at the expense of broader ones. A sharp low intensity peak at g ~ 2 from an organic impurity is observed in all of the spectra. The improved S/N for the field-stepped spectrum provides improved definition of the very weak forbidden transitions that fall between the stronger hyperfine lines (insets below trace B and above trace C).

Figure 10.

A) Spectrum of Mn2+ in CaO obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 1201 steps over 600 G. Each scan was 11.5 G wide and the linear scan frequency was 5.12 kHz, which corresponds to a scan rate of 118 kG/s. B) The first derivative of the spectrum in part A, and C) the CW spectrum obtained with a modulation amplitude of 0.15 G and 0.1 G field resolution. The insets below trace B and above trace C show the forbidden transitions with y axis scales expanded by a factor of 20. The B1 was 17.4 mG for both spectra.

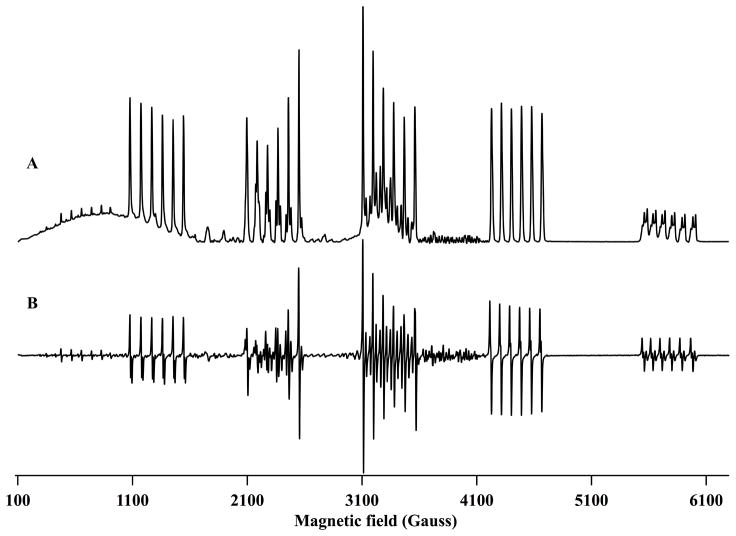

The spectrum of Mn2+ in a crystal of Mg(acac)2(H2O)2 is especially challenging. The zero field splitting is large enough that the spectrum extends over more than 6000 G. The narrowest lines have peak-to-peak linewidths in the first derivative spectrum of about 5 G. The spectrum was strongly orientation dependent. Data obtained for the same orientation of the crystal by field-stepped direct detection or by CW are shown in Fig. 11. The field-stepped spectrum was obtained with 6201 steps over 6200 G. A broad feature at low field was well-defined in the field-stepped absorption spectrum.

Figure 11.

A) Spectrum of an oriented crystal of Mn2+ in Mg(acac)2(H2O)2 obtained by field-stepped direct detection in 6201 steps over 6200 G. B) CW spectrum obtained with a modulation amplitude of 1.1 G and field resolution of 1.0 G. The B1 was 174 mG for both spectra.

The S/N for spectra in Figures 6 to 11 is summarized in Table 1. The samples for which spectra are reported in the paper were selected to demonstrate the ability of the stepped-field method to accurately record complicated lineshapes. The experimental conditions were selected to give high enough S/N that lineshapes were well defined. For most of the spectra the S/N is so high that the noise is not well defined, and there is substantial uncertainty in the calculated values of S/N. However, the S/N advantage of stepped field scan relative to conventional CW is evident (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Sample | Figure | Field-Stepped Absorption | Field-Stepped First Derivative | CW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2+ in Ni(Et2dtc)2 | 6 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Cu2+ in ZnTTP | 7 | 3.0 | 0.72 | 0.30 |

| PDT in sucrose octaacetate | 8 | 11 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| VO2+ in Zn(TTP-COOH) | 9 | 13 | 2.6 | 1.1 |

| Mn2+ in CaO | 10 | 11 | 8.5 | 2.3 |

| Mn2+ in Mg(acac)2(H2O)2 | 11 | 11 | 2.0 |

S/N for the absorption spectra is defined as signal amplitude divided by RMS noise in baseline regions of the spectrum. For the first derivative spectra the S/N is defined as the peak-to-peak amplitude divided by RMS noise in baseline regions of the spectrum.

The S/N for many spectra is so high that it is difficult to define the RMS noise accurately.

All values are reported in units of 103.

5. Discussion

The field-stepped direct detection spectra for samples with sweep widths ranging from 2 to 6200 G are in excellent agreement with CW spectra. The spectra include both lines that are narrow or broad relative to the sweep width. This method has several advantages relative to CW spectroscopy, several of which are similar to the advantages of rapid scan [1]. (i) In CW if the modulation amplitude is too large, the signal is broadened. In direct detection field modulation is not used. (ii) In CW the small modulation amplitude detects only a small fraction of the signal amplitude. In direct detection each scan detects a larger fraction of the signal, which improves the S/N. (iii) If the scan rate is fast enough to cause rapid scan oscillations, the slow scan spectrum can be recovered by deconvolution after the combination. (iv) The data are acquired with quadrature detection, which permits phase correction in the post processing. (v) In the direct detection method the signal typically is oversampled in the field axis. The appropriate number of points to be averaged to achieve the desired field resolution is determined in post processing, which improves the S/N. For many of the spectra shown in the figures, about 100 points were averaged.

Very wide triangular or sinusoidal scans lead to large background signals that are due to the effects of the scanning magnetic field [1]. In the direct detected scans the background signal is nearly sinusoidal at the scanning frequency. Additional advantages of the field swept direct detection method are that i) the background signal is much lower for the individual scans than for the combined wide spectrum, and ii) The background signals for the individual scans are not coherent with the combined spectrum and tend to average out similar to noise when repetitive signals are averaged. The residual absorption signal after DC offset correction is slowly varying and monotonic (Fig. 5D), similar to backgrounds in CW spectra. The selection of the number of scans and the field increment between scans determines the accuracy with which the field is defined at each point in the spectrum. Combining the signals from separate scans requires accurate alignment of field points from successive scans. This resolution can be improved by interpolation as was demonstrated for the LiPc data.

This method extends the advantages of rapid scan to much wider sweeps than are feasible for a single scan. The widest scans that have been reported for a single rapid scan was 155 G [6]. The non-adiabatic rapid sweep method (NARS) of Hyde and co-workers also employs direct detection [18, 20–22]. The widest scan obtained by that method had a sweep width of 850 G, which was obtained by combining 170 segments of 5 G each [18]. The segments were combined by aligning only the ends of the segments and the use of a low-pass filter to remove discontinuities created by combing segments. A major advantage of the proposed field-stepped direct detection method is that there are extensive regions of overlap between successive scans, which results in minimum discontinuity between segments. In parallel with the work reported in this paper, Kittell and Hyde [22] reported using overlapping segments.

Research Highlights.

Wide EPR absorption spectra are acquired using rapid scan technology.

Many extensively overlapped direct-detected triangular field scans are combined.

Lineshapes are in excellent agreement with CW spectra for sweep widths of 150 to 6200 G.

Signal-to-noise advantages relative to CW are similar to rapid scan.

Acknowledgments

Support of this work by National Science Foundation grant MRI 1227992 (SSE and GRE) and National Institutes of Health CA177744 (GRE and SSE) is gratefully acknowledged. The rapid scan hardware was developed by Richard W. Quine [15] and his suggestions were helpful in implementing the methodology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eaton SS, Quine RW, Tseitlin M, Mitchell DG, Rinard GA, Eaton GR. Rapid Scan Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. In: Misra SK, editor. Multifrequency Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Data and Techniques. Wiley; 2014. pp. 3–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell DG, Tseitlin M, Quine RW, Meyer V, Newton ME, Schnegg A, George B, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. X-Band Rapid-scan EPR of Samples with Long Electron Relaxation Times: A Comparison of Continuous Wave, Pulse, and Rapid-scan EPR. Mol Phys. 2013;111:2664–2673. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tseitlin M, Yu Z, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Digitally generated excitation and near-baseband quadrature detection of rapid scan EPR signals. J Magn Reson. 2014;249:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi JP, Ballard JR, Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Rapid-Scan EPR with Triangular Scans and Fourier Deconvolution to Recover the Slow-Scan Spectrum. J Magn Reson. 2005;175:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseitlin M, Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Deconvolution of Sinusoidal Rapid EPR Scans. J Magn Reson. 2011;208:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Z, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Tseitlin M, Elajaili H, Kathirvelu V, Clouston LJ, Boratyński PJ, Rajca A, Stein R, Mchaourab H, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Rapid-Scan EPR of Immobilized Nitroxides. J Magn Reson. 2014;247:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turek P, Andre JJ, Giraudeau A, Simon J. Preparation and study of a lithium phthalocyanine radical: optical and magnetic properties. Chem Phys Lett. 1987;134:471–476. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grinberg VO, Smirnov AI, Grinberg OY, Grinberg SA, O’Hara JA, Swartz HM. Practical conditions and limitations for high spatial resolution of multi-site EPR oximetry. Appl Magn Reson. 2005;28:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du JL, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Temperature and orientation dependence of electron-spin relaxation rates for bis(diethyldithiocarbamato)copper(II) J Magn Reson A. 1995;117:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du JL, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Electron spin relaxation in vanadyl, copper(II), and silver(II) porphyrins in glassy solvents and doped solids. J Magn Reson A. 1996;119:240–246. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Z, Tseitlin M, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Multiharmonic Electron Paramagnetic Resonance for Extended Samples with both Narrow and Broad Lines. J Magn Reson. 2015;254:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Such KP, Lehmann G. E. P. R. of Mn2+ in acetylacetonates. Mol Phys. 1987;60:553–560. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charles RG, Holter SN, Fernelius WC. Manganese(II) Acetylacetonate. In: Rockow EG, editor. Inorganic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, N. J: 1960. pp. 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseitlin M, Mitchell DG, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Corrections for sinusoidal background and non-orthogonality of signal channels in sinusoidal rapid magnetic field scans. J Magn Reson. 2012;223:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quine RW, Czechowski T, Eaton GR. A Linear Magnetic Field Scan Driver. Conc Magn Reson B (Magn Reson Engin) 2009;35B:44–58. doi: 10.1002/cmr.b.20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell DG, Quine RW, Tseitlin M, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. X-band Rapid-Scan EPR of Nitroxyl Radicals. J Magn Reson. 2012;214:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi JP, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Impact of Resonator on Direct-Detected Rapid-Scan EPR at 9.8 GHz. Appl Magn Reson. 2005;28:239–249. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyde JS, Bennett B, Kittell AW, Kowalski JM, Sidabras JW. Moving difference (MDIFF) non-adiabatic rapid sweep (NARS) EPR of copper(II) J Magn Reson. 2013;236:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du JL, More KM, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Orientation dependence of electron spin phase memory relaxation times in copper(II) and vanadyl complexes in frozen solution. Israel J Chem. 1992;32:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kittell AW, Hustedt EJ, Hyde JS. Inter-spin distance determination using L-band (1–2 GHz) non-adiabatic rapid sweep paramagnetic resonance (NARS EPR) J Magn Reson. 2012;221:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kittell AW, Camenisch TG, Ratke JJ, Sidabras JW, Hyde JS. Detection of undistorted continuous wave (CW) electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra with non-adiabatic rapid sweep (NARS) of the magnetic field. J Magn Reson. 2011;211:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kittell AW, Hyde JS. Spin-label CW microwave power saturation and rapid passage with triangular non-adiabatic rapid sweep (NARS) and adiabatic passage (ARP) EPR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 2015;255:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]