Abstract

IL-5 is a major therapeutic target to reduce eosinophilia. However, all of the eosinophil-activating cytokines IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF are typically present in atopic diseases including allergic asthma. Due to the functional redundancy of these 3 cytokines on eosinophils and the loss of IL-5 receptor on airway eosinophils, it is important to take IL-3 and GM-CSF into account to efficiently reduce tissue eosinophil functions. Moreover, these 3 cytokines signal through a common β-chain receptor, and yet differentially affect protein production in eosinophils. Notably, the increased ability of IL-3 to induce production of proteins such as semaphorin-7A without affecting mRNA level suggests a unique influence by IL-3 on translation. The purpose of this study is to identify the mechanisms by which IL-3 distinctively affects eosinophil function compared to IL-5 and GM-CSF, with a focus on protein translation. Peripheral blood eosinophils were used to study intracellular signaling and protein translation in cells activated with IL-3, GM-CSF or IL-5. We establish that, unlike GM-CSF or IL-5, IL-3 triggers prolonged signaling through activation of ribosomal protein (RP) S6 and the upstream kinase, p90S6K. Blockade of p90S6K activation inhibited phosphorylation of RPS6 and IL-3-enhanced semaphorin-7A translation. Furthermore, in an allergen-challenged environment, in vivo phosphorylation of RPS6 and p90S6K was enhanced in human airway compared to circulating eosinophils. Our findings provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying differential activation of eosinophils by IL-3, GM-CSF, and IL-5. These observations place IL-3 and its downstream intracellular signals as novel targets that should be considered to modulate eosinophil functions.

Keywords: Human, eosinophils, cell activation, cytokine, IL-3, allergen, P90S6K, RPS6, signal transduction, protein translation, semaphorin-7A, allergy, asthma, lung

Introduction

Mature eosinophils are non-dividing, innate immune cells with a limited (~3 d) circulating life-span. Eosinophilia is found in a variety of diseases including the hypereosinophilic syndromes, eosinophilic esophagitis, atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic asthma. Numerous in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that eosinophils trigger tissue damage, influence the immune response (1) and drive tissue fibrosis by release of toxic granule proteins, leukotrienes, cytokines and chemokines (2). In asthma, disease severity, chronicity and exacerbations are frequently associated with airway eosinophilia (3). Depletion of eosinophils in allergen-challenged animals reduced collagen deposition, mucus production and airway hyper-responsiveness (4, 5). In aggregate, these studies establish a critical role for eosinophils in asthma pathogenesis.

IL-5 regulates the differentiation, survival and function of eosinophils. The nearly exclusive presence of IL-5 receptor-α (IL-5RA) on eosinophils made IL-5 an ideal drug target to reduce eosinophilia. Several therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-5RA) are currently in phase III clinical trials (6). In asthma, these antibodies dramatically decreased peripheral blood eosinophils but had much less effect on reducing airway eosinophil numbers (~50%) (7). Yet, this decline of tissue eosinophils by anti-IL-5 therapy reduced asthma exacerbations by ~50% and decreased the use of corticosteroids in severe asthmatic subjects with previously demonstrated persistent airway eosinophilia (8, 9). However, in a more general asthma population, anti-IL-5 failed to improve symptoms and pulmonary functions (10). We have previously shown that airway eosinophils from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) lose their IL-5RA and do not degranulate in response to IL-5 (11), and that the upregulation and activation of β2 integrins on airway eosinophils is not affected by treatment with anti-IL-5, even though β2 integrin levels and activation state on blood eosinophils are decreased (12). These observations support the idea that other factors, besides IL-5, are important for airway eosinophil presence and activation.

IL-5, GM-CSF and IL-3 initiate signaling via a common β-chain receptor, and have been termed βc receptor-signaling cytokines. IL-3 and GM-CSF are far more pleiotropic than IL-5, but all three are thought to have largely redundant functions on eosinophils. Mounting evidence suggest this is an oversimplification. We, and others have shown that IL-3 alone or associated with TNF-α was more potent than IL-5 or GM-CSF to induce the production and release of proteins from eosinophils (13–15). These studies demonstrate that IL-3, IL-5 and GM-CSF have unappreciated distinct roles in eosinophil biology and by inference, asthma and allergy.

IL-3 is relevant in asthma, and allergy in general, since it is released by activated Th-2 lymphocytes and by mast cells or basophils following IgE cross-linking (16). Serum IL-3 levels are significantly elevated in poorly controlled asthmatics and plasma levels are elevated in patients with asthma or airway allergy (17–19), supporting a role of IL-3 in asthma. Moreover, IL-3-positive cells are more abundant in bronchoalveolar lavage cells or ex vivo activated T cells from subjects with asthma compared to control subjects, and their numbers increase with asthma severity (19). Finally, airway allergen challenge in subjects with mild asthma leads to increased levels of IL-3 in the BAL fluid (1, 20).

Recently, we have reported that human airway eosinophils expressed more of the pro-fibrotic membrane protein semaphorin-7A than blood eosinophils following an airway allergen challenge (15). Blood eosinophils treated ex vivo with IL-3 but not GM-CSF or IL-5 showed an important increase of semaphorin-7A protein without changes in semaphorin-7A mRNA levels. Consistent with an effect on translation, we found more semaphorin-7A mRNA associated with polyribosomes after IL-3 signaling (15). In order to test the hypothesis that IL-3 regulates translation, we now examine the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6). RPS6 is one of the two ribosomal proteins susceptible to phosphorylation following cellular stimulation by cytokines (21, 22). In stromal cells, RPS6 phosphorylation is controlled by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and downstream by the kinases, p70S6K1 and p70S6K2 (23). In genetically modified RPS6 (knock-in) mice with alanine substitutions at all 5 phosphorylatable serine residues, global protein synthesis was decreased in liver and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (24). These results are consistent with other studies showing a positive role of RPS6 phosphorylation in the initiation of translation, probably through more efficient 40S ribosomal subunit assembly (25). Phosphorylated RPS6 is located near the mRNA and tRNA-binding sites at the interface between the small and the large ribosomal subunits (26), and polyribosomes display a higher level of RPS6 phosphorylation than the ribosomes (21).

The correlation of RPS6 phosphorylation with cell division during mitogenic activation suggests that RPS6 controls mRNA translation in dividing cells (27). Phosphorylation of RPS6 via mTORC1 occurs in tumor cells, and a lack of phosphorylation is associated with reduced development of pancreatic cancer in mice (28). However, the role of phosphorylated RPS6 in non-dividing cells, such as eosinophils, is unknown. The aim of the present study was to analyze the possible role of RPS6 in IL-3-induced semaphorin-7A mRNA translation in eosinophils, and to identify intracellular signaling pathways upstream of RPS6 to understand the differential induction of eosinophil semaphorin-7A by IL-3 versus IL-5- and GM-CSF.

Materials and Methods

Subjects, cell preparations and cultures

The study protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained from subjects prior to participation.

Sixty subjects were used to study peripheral blood eosinophils. Among them, 48 had both mild asthma and allergy, 11 had allergy only and 1 had asthma only. Four of the 60 subjects had prescriptions for low doses of inhaled corticosteroids, which were not used the day of the blood draw. Peripheral blood eosinophils were purified by negative selection as previously described (15). Eosinophil viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. Eosinophil preparations with purity and viability >99% were used. Eosinophils (1×106/ml) were maintained in complete medium (RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal bovine serum) at 37°C with or without recombinant human (rh) IL-5, GM-CSF or IL-3 (2 ng/ml, unless indicated). RhGM-CSF was purchased from R&D Systems Inc (Minneapolis, MN, USA), while rhIL-3 and rhIL-5 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). In a previous study, rhGM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 prepared in E. coli and insect cells showed uniformities among vendors regarding eosinophil activation and protein release (14).

Bronchoscopy and BAL were performed before and 48 h after segmental bronchoprovocation with an allergen (SBP-Ag) in subjects allergic to ragweed, pollen or cat and with a history of mild asthma (15). Eosinophils were purified from the BAL cell preparation (BAL EOS (AG)) and from peripheral blood (PB EOS (AG)) of the same allergen-challenged patient. On the same day, eosinophils were also purified from peripheral blood of a control unchallenged subject (PB EOS (CTRL)). Methods for preparation of airway eosinophils were previously described (15). Immediately after eosinophil preparation, cell pellets were stained for flow cytometry analysis or were snap-frozen and stored at −80°C for further analysis by Western blot.

Cytokine (IL-3, IL-5, GM-CSF) consumption and ELISA

Cytokines (2ng/ml) were added to peripheral blood eosinophils in RPMI plus 10% FBS at the beginning of the culture. Cytokines left in culture over time were measured by two-step sandwich ELISAs as previously described (29) Unlabeled (coating) and biotinylated (detecting) anti-IL-3 and anti-IL-5 antibodies and corresponding recombinant protein standards for ELISA were from BD Biosciences. Unlabeled and biotinylated anti-GM-CSF antibodies and recombinant protein standard for ELISA were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The assay sensitivities were below 3 pg/ml for GM-CSF and IL-5, and 12 pg/ml for IL-3.

Western blot

Cells were lysed either in RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) plus 0.2 % SDS and protease inhibitors, or directly in Laemmli buffer (10% SDS), before boiling and loading onto 10–12% SDS-page gels. Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (14). Rabbit monoclonal antibodies anti-RPS6, anti-RPS6-S235/236, anti-Akt-S473, anti-p70S6K-T389, anti-eIF2α-S51, anti-eIF4E-S209, anti-4E-BP1-T37/T46, anti-RSK1/2/3, anti-RSK1 (p90S6K1)-380, anti-RSK1-T573, anti-RSK1-T359/S363 and anti-eIF4B-S422 were all from Cell Signaling. Secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were from either Cell Signaling or Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, WI). Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin was purchased from Sigma. Goat polyclonal anti-semaphorin-7A antibody was from R&D Systems. Donkey anti-goat antibody was from Santa Cruz. Immunoreactive bands were visualized with Super Signal West Femto chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific). Bands were quantified using the FluorChem® Q Imaging System (Alpha Innotech/ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Reagents

LY294002, rapamycin, calyculin A and okadaic acid were purchased from Cell Signaling. BI-D1870 and PF-4708671 were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA). U0126, its inactive analog U0124 and SB203580 are from Calbiochem/EMD Millipore. Cycloheximide was bought from Calbiochem. The neutralizing anti-IL-3 antibody and the control goat IgG were purchased from R&D Systems.

Fluorescent Microscopy

ER-Tracker™ Dyes (Molecular ProbesTM, Invitrogen detection technologies, Eugene, OR, USA) was used on living cells during the last 30 min of culture. Cytospins were prepared and cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100. Following incubation with anti-RPS6-S235/236 (Cell Signaling), cells were treated with 0.2% chromotrope-2R to quench non-specific autofluorescence, and then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (A10530; Invitrogen). Images were collected by fluorescence microscopy and analyzed with ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html). Fluorescence of cells was counted in a ‘blinded’ way in random visual fields. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to objectively quantify co-localization of phospho-RPS6 (S235/236) to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (30). Scatter plots representing pixel intensities were generated and the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between red and green pixels were calculated using ImageJ software with a co-localization plugin (Colo2). A coefficient close to 1 indicates good co-localization while a coefficient close to 0 indicates poor co-localization.

Measurement of translation

The determination of translation was performed using the Click-iT® Labeling Technology (Life Technologies, USA). Fourteen h after the beginning of activation, eosinophils were centrifuged and re-cultured in methionine-free RPMI-1640 plus 10% FBS and cytokine (2ng/ml) for 1 h before adding a non-radioactive amino acid (L-azidohomoalanine, 50μM) for 4 h. After the amino acid pulse, cells were pelleted, washed twice with PBS and snapped frozen at −80°C. Cells pellets were lysed in Tris-HCl buffer containing 1% SDS, and phosphatase and protease inhibitors. The L-azidohomoalanine present in the cell lysate was then chemically ligated (“clicked”) to an alkyne-modified biotin. Proteins were precipitated with methanol/chloroform and suspended in Laemmli buffer for separation in a 10% SDS-page gel. After transfer onto PVDF the newly synthesized proteins (biotin-labelled) were visualized using streptavidin-HRP. Signals were quantified as described above in “Western blot”. When indicated, the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase inhibitor (p90S6K) inhibitor BI-D1870 or the p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (RP70SK6) inhibitor PF-4708671 was added 15 min before IL-3. For semaphorin-7A immunoprecipitation following the Click-iT® labeling procedure, proteins precipitated with methanol/chloroform were suspended in RIPA buffer and immunoprecipitated using 4 μg of a goat anti-semaphorin-7A (R&D Systems) and protein G beads (Millipore). After an overnight incubation at 4°C, beads were washed 4 times, suspended in the Laemmli loading buffer and run in a 10% SDS page gel. Immunoblotting for total semaphorin-7A was performed using a goat anti-semaphorin-7A from R&D Systems and a donkey anti-goat from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Newly synthetized immunoprecipitated semaphorin-7A protein was visualized using streptavidin-HRP.

Flow cytometry

Purified blood eosinophils were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD208 (semaphorin-7A), FITC-conjugated anti-GM-CSFRα (CD116), PE-conjugated anti-IL3Rα (CD123) or PE-conjugated anti-IL-5Rα (CD125) and a corresponding isotype control (BD Pharmingen™, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Blood eosinophils after an allergen challenge (PB EOS (AG)) or airway eosinophils after an allergen challenge (BAL EOS (AG)) were stained from whole blood or total BAL cells as previously described (15). Ten thousand cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded using propidium iodide. Data were analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA) and expressed as geometric mean or median channel fluorescence of specific stain.

Polyribosome preparation

Blood EOS were activated with either IL-3 or GM-CSF (2 ng/ml) for 14 h. Cells (6 × 106) were washed with PBS and polyribosomes were prepared as previously described (15). The polyribosome pellet was then washed once with the lysis buffer without detergent and then lysed in TRIzol® (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for RNA extraction.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from eosinophils or the polyribosome preparation using either the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) or TRIzol®reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), respectively. Reverse transcription reaction was performed using the Superscript III system (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). mRNA expression was determined by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using SYBR Green Master Mix (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA) as previously described. Specific primers shown in the supplementary Table 1 were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and blasted against the human genome to determine specificity using http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast. The reference gene, β-glucuronidase (GUSB), forward: CAGGACCTGCGCACAAGAG, reverse: TCGCACAGCTGGGGTAAG), was used to normalize the samples. Polyribosomes were quantified by the 18S RT-qPCR using the TaqMan human 18S rRNA endogenous control primers (reference sequence: X03205.1) and hydrolysis probe (VICR/MGB probe, Life Technologies). Applied Biosystems (ABI/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) 7500 Sequence detector was used. Standard curves were performed and efficiencies were determined for each set of primers. Efficiencies ranged between 93 and 96%. Data are expressed as fold change using the comparative cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method as described previously (1, 15).

Phosphatase activity

Eosinophils were lysed with Tris-HCl (50 mM), NaCl (150 mM), 0.05% SDS and protease inhibitors. Phosphatase activity in cell lysates was measured using the EnzChek® Phosphatase Assay Kit, as recommended by the provider (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The fluorescence was measured by a plate reader (Synergy HT, Biotek Instruments, Inc, Vermont, USA) using excitation at 350 nm and emission at 450 nm.

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups were analyzed using the unpaired or paired Student’s t-test and the SigmaPlot 11.0 software package. In Fig. 4A the ratios P90S6K-S380/Total P90S6K and RPS6 S235-S236/Total RPS6 were compared by source (PB EOS (CTRL), PB EOS (AG), BAL EOS (AG)) using mixed-effect linear models with a fixed effect for source and a random effect for experiment to account for within-experiment and within-donor correlation.

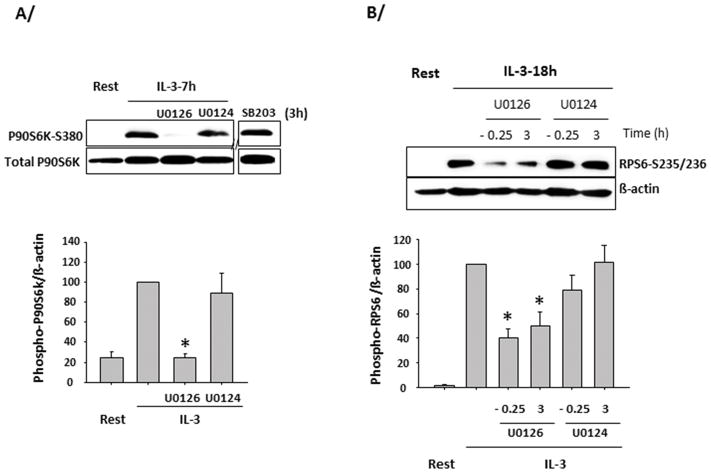

Figure 4. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) controls p90S6K and S6 protein phosphorylation.

Blood eosinophils were treated with or without inhibitors and activated with IL-3 (2 ng/ml) for analysis of p90S6K (P90S6K-S380) and S6 (RPS6-S235/236) phosphorylation. A representative blot is shown and graphs are averages ± SD of 3 experiments using 3 different donors. The value for IL-3-activated cells with no treatment is fixed at 100. A/ EOS were activated for 3 h with IL-3 and then treated with the inhibitor of p38 (SB203580, SB203), the inhibitor of ERK (U0126) and its inactive analog (U0124) for the remaining 4 h. On the graph, * indicates P90S6K phosphorylation is significantly lower compared to treatment with the analog U0124. B/ EOS were pretreated with U0126 or U0124 for 15 min (−0.25) and activated with IL-3 for 18 h, or were activated for 3 h with IL-3 and then treated with U0126 or U0124 for the remaining 15 h. On the graph, * indicates phosphorylation was significantly lower in U0126-treated cells compared to its respective control treated with its inactive analog (U0124).

Results

Eosinophils consume a large amount of IL-3

Exposure to > 6 pM concentrations of IL-5, GM-CSF or IL-3 increases eosinophil viability after a 1 day culture. However, concentrations between 250–700 pM are often used to evoke changes in eosinophil morphology, gene expression or protein secretion. In the present study, unless indicated, the three βc receptor-signaling cytokines were used at 2 ng/ml (~ 130 pM). This concentration was chosen as the three cytokines have a very similar effect on eosinophil survival during the first 6 days in culture (Supplementary Fig. 1). Longer term cultures (12 days) demonstrated that GM-CSF was significantly superior to IL-5 or IL-3 in promoting survival (Supplementary Fig. 1).

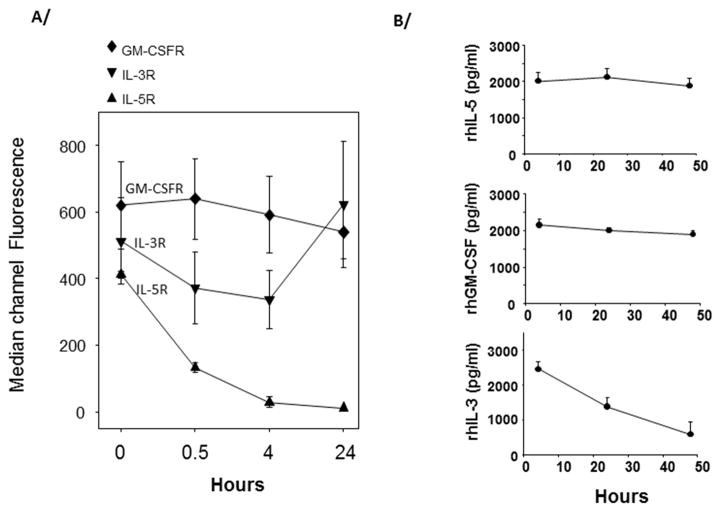

The cell-surface level of the ligand-binding α-chains of the IL-5, GM-CSF, and IL-3 receptors are differentially controlled by these cytokines. As previously described, IL-5 induced rapid loss of IL-5RA on eosinophils (31) (Fig. 1A). Conversely, over the same time period, IL-3 increased IL-3RA while GM-CSF has no effect on its own α-chain receptor (CSF2RA, also called GM-CSFR) (Fig. 1A). In accordance with the receptor expression, cytokine consumption over a period of 48 h was minimal when 1 million eosinophils were cultured with recombinant human (rh) IL-5 (2 ng/ml) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, as much as 2 ng of rhIL-3 were consumed by eosinophils, while only about 200 pg/ml of the 2 ng/ml of rhGM-CSF were used (Fig. 1B). Of note, rhIL-3 did not degrade when incubated at 37°C for 48 h in cell-free medium or conditioned medium from GM-CSF-activated eosinophils (data not shown). These results suggest that the βc receptor-signaling cytokines drive different outcomes in eosinophils, including continuous signaling downstream of the IL-3/IL-3 receptor complex.

Figure 1. Regulation of the GM-CSF, IL-3, and IL-5 α chain receptors, and consumption of GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 by blood eosinophils.

A/ Eosinophils were activated with GM-CSF, IL-3 or IL-5 for the indicated times and levels of their respective α chain receptors (GM-CSFR, IL-3R or IL-5R) were measured by flow cytometry. B/ Eosinophils were cultured in 24 well-plates at 1×106 cells per ml per well. Recombinant human (rh) cytokines (2ng/ml) were added at time 0. One hundred μl of cell culture was harvested at times 0, 24 h and 48 h and the concentration of cytokines remaining in the cell cultures was determined by ELISA. The average ± SD of 3 experiments with 3 different donors is shown for A/ and B/.

IL-3 induces and prolongs ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation

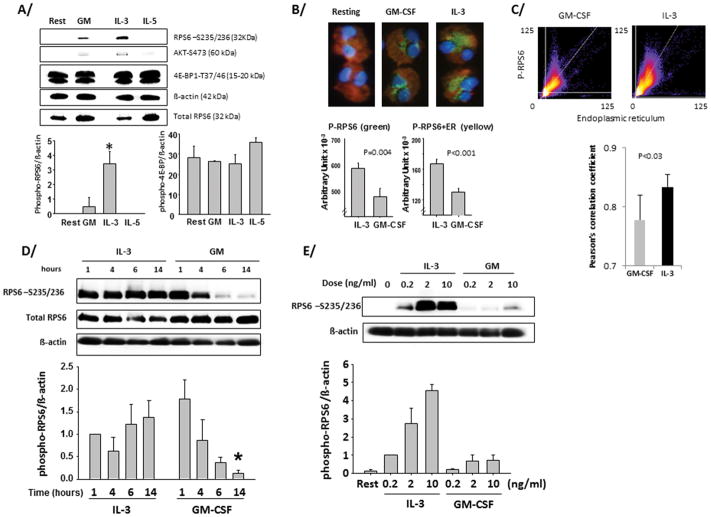

Among the ribosomal proteins, ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6) has been characterized for its ability to be phosphorylated following cell activation. Thus, we asked if βc receptor-signaling cytokines altered RPS6 phosphorylation state in eosinophils. Indeed, IL-3 triggered the phosphorylation of RPS6 (Fig. 2A). Phosphorylation was not detected in IL-5-activated eosinophils and only a modest phosphorylation of RPS6 was observed in cells treated with GM-CSF for 14 h (Fig. 2A). These results were confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2B), which revealed that phosphorylated RPS6 was perinuclear and associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (P-RPS6+ER. A comparison of Pearson’s correlation coefficients of red and green pixel intensities demonstrated that co-localization of phospho-RPS6 and ER was greater in IL-3 versus GM-CSF-activated eosinophils (Fig. 2C). Notably, Akt (Fig. 2A) or p70S6 kinase phosphorylation was marginally detectable and the phosphorylation of the eukaryotic initiation factors (eIF2α and eIF4E) was undetectable. EIF4E-binding protein (4E-BP1), a repressor of translation in its non-phosphorylated state was strongly phosphorylated in both resting and cytokine-activated eosinophils (Fig. 2A) suggesting 4E-BP1 does not regulate translation in eosinophils under these conditions. Kinetic studies revealed that GM-CSF induced rapid and transitory phosphorylation of RPS6 that was lost between 4 and 6 h (Fig. 2D). However, phosphorylation was maintained in IL-3-activated eosinophils over a period of 14 h (Fig. 2D). Dose response studies (Fig. 2E) showed that significant and prolonged RPS6 phosphorylation was detectable even at low doses of IL-3 (0.2 ng/ml), and was not significantly increased at concentrations higher than 2 ng/ml. On the other hand, even at 10 ng/ml GM-CSF had little effect on RPS6 protein phosphorylation (Fig. 2E). These data show differential signaling mediated by βc receptor-signaling cytokines that culminate in RPS6 phospho-status.

Figure 2. Prolonged phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 in IL-3-activated eosinophils.

Blood eosinophils (1×106 cells/ml) were cultured in 24-well plates with 10% FBS and with GM-CSF (GM), IL-3, or IL-5 or with no cytokines (resting/rest) for 14 h (A/B/C/E) or for the indicated times in D/. (A/D/E) Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer plus 0.2% SDS. Cell lysates were blotted with the indicated antibodies. A representative blot is shown and quantification of 3 experiments using 3 different donors is displayed below each blot. B/ and C/ Cells were stained in red using the ER-tracker™Dyes. After cytospin, cells were stained using the anti-phospho-RPS6 (S235/236) (green) and DAPI (blue). C/ Co-localization of phospho-RPS6 and ER was analyzed by distribution of pixel intensities for phospho-RSP6 (y-axis) and for ER (x-axis) in GM-CSF- and IL-3-stimulated eosinophils. A comparison of the average Pearson’s correlation coefficients for 5 individual eosinophils stimulated are displayed below. (1 = perfect correlation, 0 = no correlation, and −1 = perfect inverse correlation.). p values are indicated (t-test). A/ * indicates a significantly higher level of phospho-RPS6 in IL-3- versus GM-CSF-activated eosinophils. D/ * indicates that the level of phospho-RPS6 at 14 h is significantly lower for GM-CSF- versus IL-3-activated eosinophils. For A/ and D/ t-test was performed and p< 0.05 was considered significant.

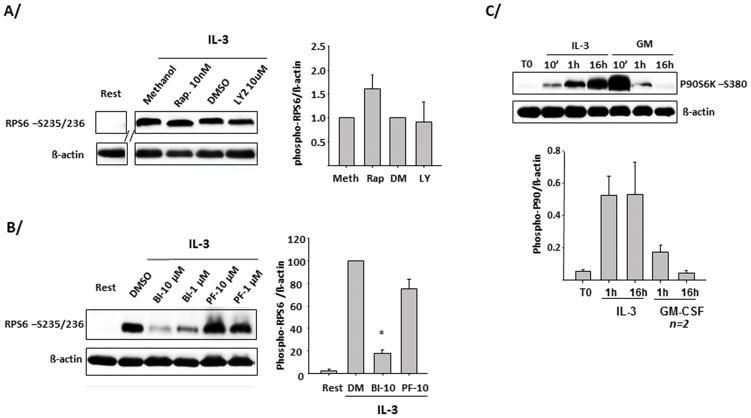

IL-3 induces and prolongs p90S6K phosphorylation upstream of RPS6

RPS6 phosphorylation is usually driven by PI3K/mTOR/p70S6K. However, in eosinophils, blockade of this pathway (PI3K with LY294002 or mTOR with rapamycin) did not prevent IL-3-induced phosphorylation of RPS6 at 14 h (Fig. 3A). Because RPS6 phosphorylation was independent of this pathway, we investigated a possible role for the 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (p90S6K, also called RSK), which is phosphorylated during cell activation and has been reported to phosphorylate RPS6 (32, 33). A P90S6K inhibitor (BI-D1870) but not an inhibitor of p70S6K activity (PF-4708671) blocked IL-3-induced RPS6 phosphorylation at 14 h (Fig. 3B). Moreover, in eosinophils, p90S6K was continuously phosphorylated by IL-3 for 16 h (Fig. 3C). In contradistinction, GM-CSF induced a strong but relatively brief (between 10 min and 1 h) phosphorylation of p90S6K (Fig. 3C). Of note, similarly to GM-CSF, IL-5 did not maintain phosphorylation of p90S6K (not shown). The prolonged phosphorylation of p90S6K in IL-3-activated eosinophils was confirmed using 2 other antibodies directed against different phospho-sites (T573- and T359-S363-p90S6K; Supplementary Fig. 2). P90S6K phosphorylation is known to be regulated by the MAPKs and particularly by ERK1/2(34). Consistent with these data, a selective inhibitor of both MEK1 and 2 (U0126) added 3 h after IL-3, blocked the phosphorylation of p90S6K on Ser380 in eosinophils for 4 h (Fig. 4A). Another MAPK, p38, has also been implicated as a potential activator of p90S6K in dendritic cells (35). However, a p38 inhibitor (SB203580) did not affect p90S6K phosphorylation in IL-3-activated eosinophils (Fig. 4A). The phosphorylation of RPS6 was also reduced by U0126 added either before or 3h after IL-3 treatment (Fig. 4B). Altogether, these data indicate that, unlike IL-5 and GM-CSF, IL-3 receptor activation leads to prolonged RPS6 phosphorylation via ERK and p90S6K but not PI3K/mTOR/p70S6K.

Figure 3. Prolonged phosphorylation of P90S6K upstream of ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation.

Blood eosinophils (1×106 cells/ml) were activated with the indicated cytokines at 2 ng/ml. Cells were lysed using Laemmli loading buffer (2% SDS). Immunoblots were performed using antibodies directed against the indicated proteins. For A/B/C/, representative blots are shown as well as graphs indicating the average ± SD of 3 experiments using 3 different donors, unless indicated. A/ Eosinophils were treated with an inhibitor of mTOR, rapamycin (10 nM) or PI3K, LY294002 (10μM), or their respective vehicles for 30 minutes before IL-3 was added for 14 h and level of RPS6 phosphorylation on serines 235 and 236 was analyzed. B/ EOS were treated with an inhibitor of p90S6K, BI-D1870 (BI), or p70S6K, PF-4708671 (PF) for 15 min before IL-3 was added for 14 h. *The level of RPS6 phosphorylation was significantly downregulated by BI-D1870 compared to treatment with PF-4708671. C/ Phosphorylated p90S6K on serine 380 was analyzed in eosinophils activated with the 3 βc receptor-signaling cytokines for the indicated times. Blots from 2 different donors are shown.

The eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF4B) is another element of the translation machinery and it is a target of p90S6K (36). In eosinophils, IL-3 induced only a slight phosphorylation of eIF4B (data not shown), providing further evidence of a novel and selective effect of IL-3 on RPS6.

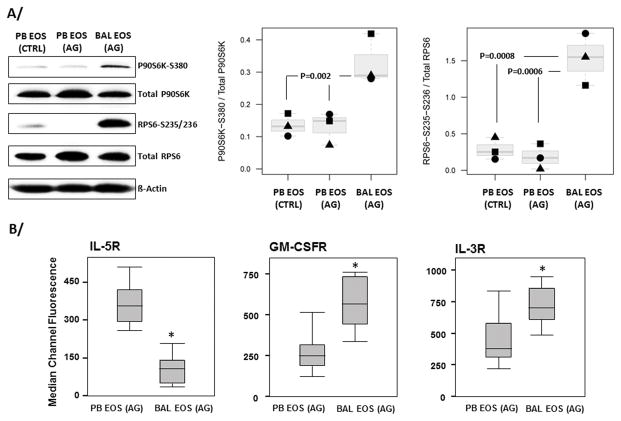

P90S6K and RPS6 are phosphorylated in vivo in airway eosinophils

To determine the relevance of our in vitro data to allergic in vivo human disease, we analyzed p90S6K1 and RPS6 phosphorylation in eosinophils isolated from BAL (BAL EOS (AG)) 48 h after a localized (segmental) airway allergen challenge. This model allows acquisition of large numbers of human eosinophils from a site of allergic inflammation (11). Fig. 5A shows robust phosphorylation of both p90S6K and RPS6 in BAL EOS compared to eosinophils isolated from the blood of the same allergen-challenged asthmatic subjects (PB EOS (AG)) or from the blood of unchallenged controls (PB EOS (CTRL)). Phosphorylated eIF4B was not detectable in either BAL EOS (AG) or PB EOS (AG).

Figure 5. P90S6K and RPS6 are phosphorylated in airway eosinophils following a SBP-Ag.

A/ Airway eosinophils (BAL EOS (AG)) were acquired by bronchoscopy performed 48 h after segmental airway allergen challenge. Circulating blood eosinophils (PB EOS (AG)) were also prepared from the same subjects 48 h after SBP-Ag. As a control, blood eosinophils (PB EOS (CTRL)) were prepared the same day from an unchallenged subject with mild atopic asthma. A representative immunoblot using the indicated antibodies is shown. Ratios of signals for phosphorylated-proteins with their respective total unphosporylated protein (P90S6K or RPS6) were performed. B/ Circulating (PB EOS) and BAL eosinophils (BAL EOS) obtained 48 h after an allergen challenge, were stained for IL5R, GM-CSFR or IL3R using blood or total BAL cells. Receptor levels were determined by flow cytometry. A/B/ Graphs shown are box plots depicting the median and the interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles for 3 subjects in A/ and 12 subjects in B/. P values are indicated on the graphs in A/ and * in B/ indicates statistically significant differences between BAL and blood eosinophils.

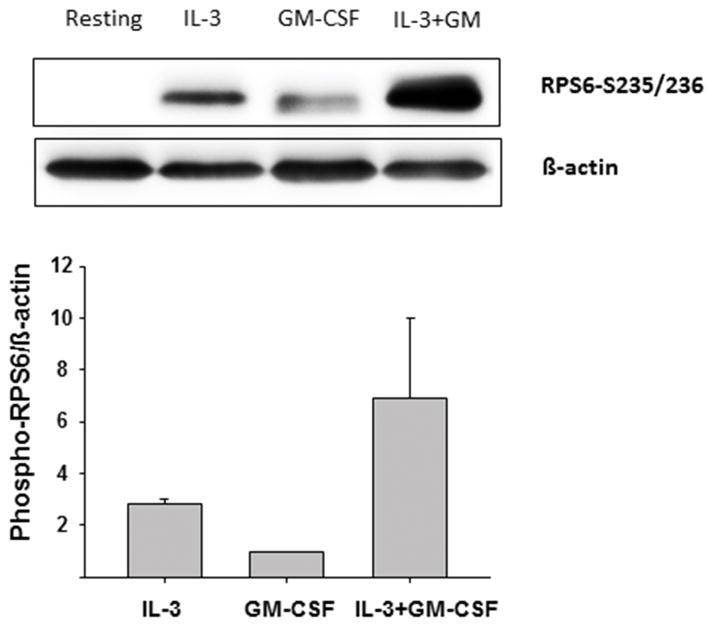

The implications of IL-3 signaling through a p90S6K/RPS6 pathway in vivo remain uncertain. Using the same in vivo model (i.e., obtaining human eosinophils 48 h after allergen challenge), BAL eosinophils displayed lower levels of IL-5RA, and higher levels of IL-3RA and GM-CSFRA compared to blood eosinophils obtained from the same allergen-challenged subjects (Fig. 5B). As both IL-3 and GM-CSF are elevated in BAL fluids 48 h after airway allergen challenge (15, 20), we asked if GM-CSF could potentially block IL-3-induced prolongation of RPS6 phosphorylation. To the contrary, in vitro stimulation of blood eosinophils with GM-CSF plus IL-3 induced greater RPS6 phosphorylation than IL-3 alone (Fig. 6). These data indicate that GM-CSF amplifies the response to IL-3, and suggests that in vivo, the presence of both cytokines may additively maintain the phosphorylation of RPS6 and p90S6K in airway eosinophils.

Figure 6. GM-CSF increases RPS6 phosphorylation in IL-3-activated eosinophils.

Blood eosinophils were treated with cytokines (each at 1 ng/ml) for 14 h. Phosphorylation of the S6 protein on serine-235/236 sites was determined by Western blot. A representative blot and a graph presenting the average ± SD of 3 experiments for 3 different donors are shown.

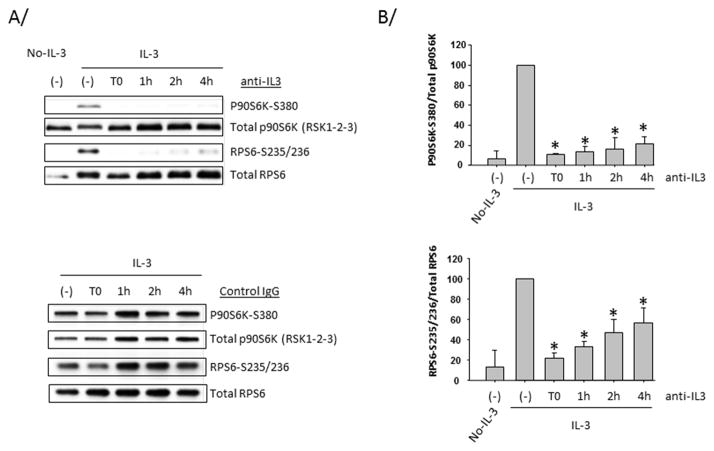

Direct effect of IL-3 on sustained intracellular signaling

The fast decrease of IL-3 receptor during the first 4 hours from the initiation of blood eosinophil activation with IL-3, combined with the consumption of IL-3 (Fig. 1), suggest that the IL-3/IL-3 receptor complex might be quickly internalized. The internalization could then trigger an IL-3-independent second signal responsible for the sustained signaling observed in eosinophils. In order to test the constant requirement of IL-3 for the maintenance of p90S6K and RPS6 phosphorylations, a neutralizing anti-IL-3 antibody was added to eosinophils at different times after the initiation of cell activation. Fig. 7 indicates that p90S6K and RPS6 phosphorylations were inhibited even when the anti-IL-3 antibody was added 4 hours after the initiation of the culture. The lack of complete inhibition of RPS6 phosphorylation might be caused by a slower turnover of phosphorylation compared to p90S6K. Fig. 7 indicates that the constant presence and direct effect of IL-3 are required to maintain signaling via p90S6K. This suggests that a second signal may not be required to maintain activation of this pathway.

Figure 7. Sustained p90S6K and RPS6 phosphorylations require the constant presence of IL-3.

Blood eosinophils were treated with IL-3 or not (No-IL-3) for 10 h. A neutralizing anti-IL-3 antibody was either not added (−) or pre-incubated with IL-3 (T0) or added to cells 1 h, 2 h or 4 h after the beginning of the activation. A/ Cell lysates were blotted using the indicated antibodies. In the bottom panel, an isotype control (goat) was used instead of the anti-IL-3 antibody. Representative immunoblots are shown. B/ Graphs represent quantification of 3 experiments using 3 different donors. * indicates that the ratio of phospho-p90S6K or phospho-RPS6 on total p90S6K or RPS6, respectively is significantly (p<0.05) lower compared to IL-3-activated cells without neutralizing antibody.

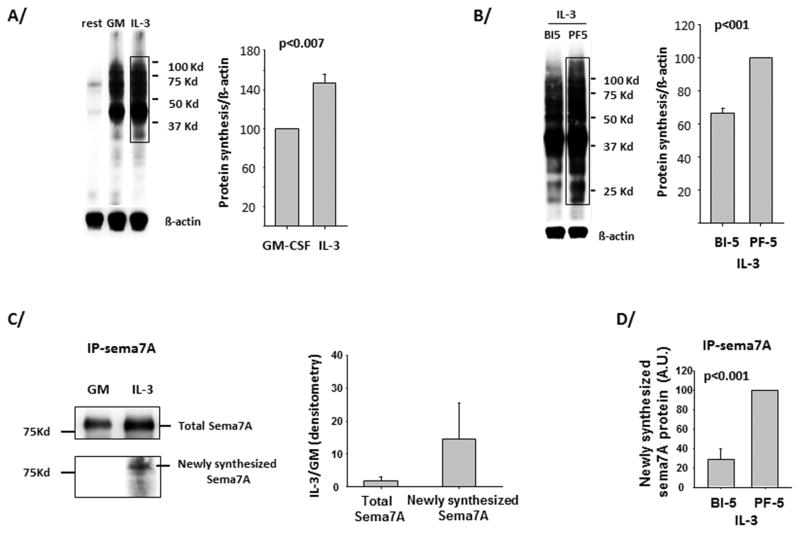

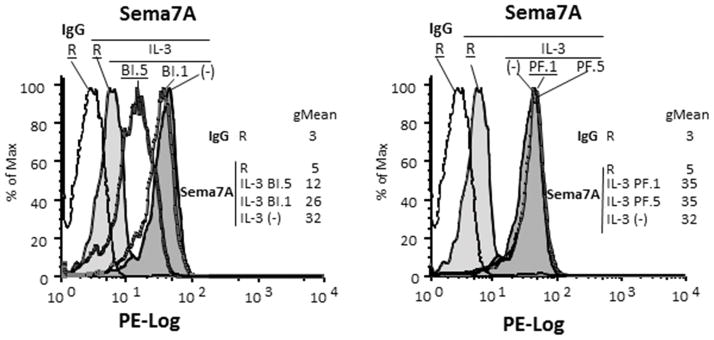

IL-3 and P90S6K control semaphorin-7A translation

To evaluate the function of IL-3 and the activation of the p90S6K/RPS6 pathway on translation, a non-radioactive, modified amino acid (L-azidohomoalanine) was pulsed into eosinophils for 4 h, 14 h after activation with either IL-3 or GM-CSF. After cell lysis, a chemo-selective ligation was performed between the incorporated amino acid and a biotin-alkyne complex. Fig. 8A shows that global translation was increased by 40% in IL-3-compared to GM-CSF-activated eosinophils and was significantly reduced by the p90S6K inhibitor BI-D1870, but not by the p70S6 kinase inhibitor PF-4708671 (Fig. 8B). Phosphorylated RPS6 has been implicated as a regulator of translatability of 5′ Terminal Oligo Pyrimidine tract (TOP) mRNAs (reviewed in (37)). Thus polyribosome preparations from eosinophils from 2 different donors were assessed for the TOP mRNA loading onto polyribosomes from IL-3-versus GM-CSF-activated eosinophils. Unlike semaphorin-7A mRNA (as previously shown in (15)), TOP mRNAs, PABP and EEF1A1 were not enriched in polyribosomes from IL-3-activated eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, a recent study showed that hypophosphorylated RPS6 in liver impaired the expression of numerous transcripts coding for proteins involved in ribosomal biogenesis (37, 38). Among these transcripts, IL-3 had no or limited effect on the expression of RRP12, NOP56 and GARE1 (data not shown).

Figure 8. Translation rate is increased in IL-3- versus GM-CSF-activated blood eosinophils and is dependent on P90S6K.

Newly synthesized protein production 14 h after activation and during the 4 h pulse with a non-radioactive amino acid (L-azidohomoalanine), was determined using the Click-iT® Labeling Technology. A/ Blood eosinophils were not treated (rest) or treated with GM-CSF (GM) or IL-3 (both at 2 ng/ml). A representative immunoblot is shown and the anti-β-actin antibody was used to quantify the amount of protein present on the blot. Signal in the drawn rectangle was quantified using the FluorChem® Q Imaging System. Average ± SD from measurements of 3 experiments using 3 different donors is shown on the graph. P<0.007 (t-test) indicates statistical significance between IL-3- and GM-CSF- treated eosinophils. B/ Eosinophils were pretreated for 30 min with BI-D1870 (BI-5) and PF-4708671 (PF-5) both at 5 μM, before IL-3 activation for 14 h. Average ± SD of 3 experiments is shown on graph. C/ Eosinophils were treated as for A/ but semaphorin-7A was immunoprecipitated after the chemical ligation and the protein precipitation stage. Upper part of blot shows total semaphorin-7A (sema7A) precipitated using goat anti-semaphorin-7A antibody. The bottom part shows the newly synthetized semaphorin-7A protein produced during the 4 h pulse with L-Azidohomoalanine. The graph presents averages ± SD of the signals obtained with IL-3- versus GM-CSF-treated eosinophils for 3 experiments using 3 different donors. D/ Eosinophils were treated in culture as in B/ and cell lysate were processed as for C/ for quantification of newly synthetized semaphorin-7A protein. The graph displays averages ± SD of 3 experiments with PF-4708671 treatment fixed at 100.

To analyze more specifically newly synthesized semaphorin-7A, semaphorin-7A protein was immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates following the chemo-selective ligation described above. While almost no detectable newly synthetized semaphorin-7A was present in GM-CSF-activated eosinophils, there was ~14 fold increase in semaphorin-7A protein from IL-3-activated eosinophils (Fig. 8C). Synthesis was dependent on p90S6K (Fig. 8D). This difference in semaphorin-7A synthesis between IL-3 and GM-CSF activation was not due to semaphorin-7A protein degradation as semaphorin-7A protein stability was unchanged after cycloheximide treatment (data not shown). Also, coding mRNA levels were very similar in IL-3-activated eosinophils treated or not with the p90S6K inhibitor, eliminating transcription or mRNA stability as a cause (data not shown).

Therefore, our data demonstrate that, compared to GM-CSF, IL-3 globally increases protein synthesis, and select mRNAs, including semaphorin-7A, are preferentially translated in a phospho-p90S6K-dependent manner.

In a previous study, we showed that IL-3 was more potent than GM-CSF or IL-5 in increasing cell-surface semaphorin-7A on eosinophils (15). Consistent with this previous study and the data described above, we find here that membrane-associated semaphorin-7A protein was reduced by p90S6K inhibition, while p70S6K blockade had no effect on membrane semaphorin-7A (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. P90S6K controls semaphorin-7A levels on eosinophils.

Blood eosinophils were treated or not (−) with either the inhibitor of p90S6K (BI-D1870) at 1 (BI 1) or 5 (BI 5) μM) or the inhibitor of p70S6K (PF-4708671 at 1 (PF 1) or 5 (PF 5) μM) for 15 min before activation with IL-3 (2 ng/ml) for 20 h. Level of semaphorin-7A was determined by flow cytometry. Levels of semaphorin-7A on resting (R) and IL-3-activated cells with or without treatment are shown. IgG control was performed for every culture conditions with no variation among the different conditions. IgG control for resting eosinophils (R) is shown. The geometric mean (gMean) for each condition is displayed. A representative experiment of 3 using 3 different donors is shown.

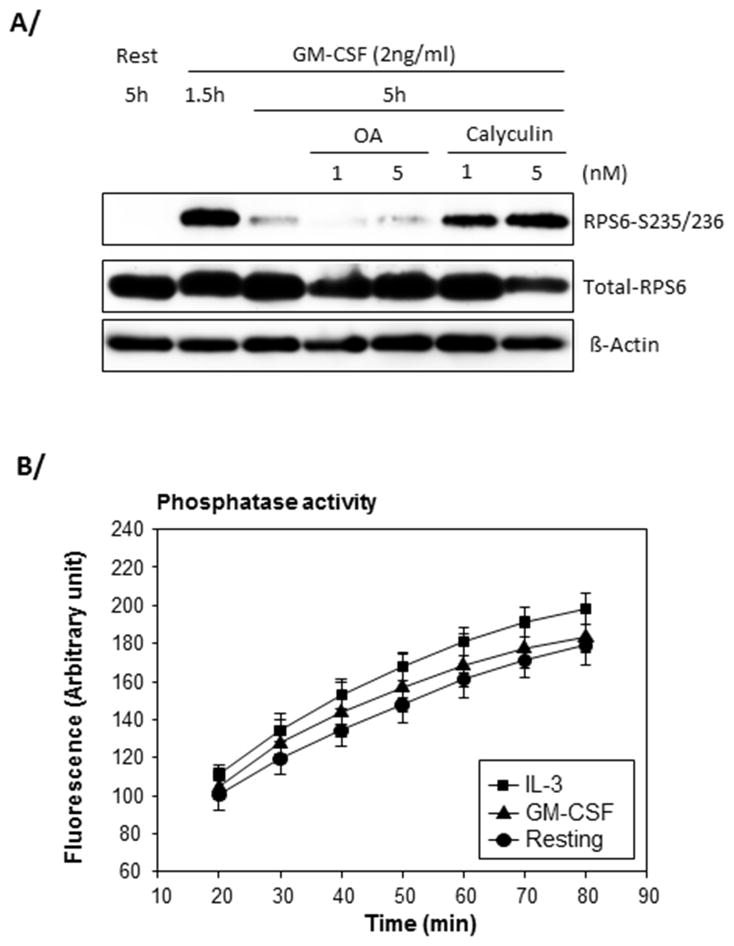

Phosphatase 1 dephosphorylates RPS6 in GM-CSF-activated eosinophils

To examine the mechanisms leading to sustained signaling in IL-3-activated cells, we sought to determine the phosphatase(s) responsible for RPS6 dephosphorylation in GM-CSF-activated eosinophils. Eosinophils were activated with GM-CSF for 5 h and treated with low doses of the phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid or calyculin during the last 3.5 h of the culture. Fig. 10A shows that calyculin was a potent inhibitor of RPS6 dephosphorylation while okadaic acid had no effect. While both compounds can inhibit both phosphatase 1 (PP1) and phosphatase 2A (PP2A), at low doses, calyculin or okadaic acid preferably inhibit PP1 or PP2A, respectively (39, 40). In accordance with previous studies (41), our data suggest that RPS6 dephosphorylation is regulated by PP1. PP1 activity was then measured in resting or activated eosinophils. PP1 activity was not significantly different in resting, IL-3 or GM-CSF-activated eosinophils (Fig. 10B) raising the possibility that specific PP1-induced RPS6 dephosphorylation is negatively regulated in IL-3-but not GM-CSF-activated eosinophils.

Figure 10. RPS6 dephosphorylation in GM-CSF-activated eosinophils is controlled by phosphatase 1 (PP1).

A/ Blood eosinophils were activated with GM-CSF for 1.5 h and low doses (1 and 5nM) of okadaic acid (OA) or calyculin were added for an extra 3.5 h. Cells were also cultured during the total 5 h in medium only (rest). The level of phosphorylation of RPS6 was analyzed by Western blot. A representative experiment of 3 is shown. B/ Eosinophils were cultured with no cytokine (resting) or IL-3 or GM-CSF (2 ng/ml) for 4.5 h. Data shown are averages ± SD of 3 experiments using eosinophils from 3 different donors. There was no statistical significance between the conditions at any time-point (t-test).

Discussion

We have shown that among the βc receptor-signaling cytokines, IL-3 is unique in prolonging the activation of p90S6K and RPS6 in human eosinophils. While phosphorylation of RPS6 by the PI3K/mTOR/p70S6K pathway is thought to regulate translation in dividing cells, in the non-dividing eosinophils, the ERK/p90S6K pathway was crucial for RPS6 activation and translation of the pro-fibrotic protein semaphorin-7A. Our data elucidate key differences in the mechanisms underlying the induction of protein translation by IL-3 versus IL-5 or GM-CSF, and suggest the importance of IL-3 signaling in mediating eosinophil function.

IL-3-activated eosinophils were unique in that p90S6K, rather than the canonical PI3K/mTOR/p70S6K pathway (23) drove RPS6 phosphorylation. P90S6K was the first RPS6-phosphorylating kinase described in Xenopus eggs (42), and has since been shown to be involved in human cell proliferation and survival (43). P90S6K includes 3 isoforms (RSK1, 2 and 3), all with inducible activity and similar functions. P90S6K is a well-known substrate for ERK and has been reported to be associated with polyribosomes in neurons (44). P90S6K has 4 phosphorylation sites that are critical for its function. ERK1/2 initially phosphorylates threonine 573 and sequentially threonine 359, serine 363 and finally serine 380 in the linker and hydrophobic motifs of p90S6K. Ultimately, 3′ –phosphoinositol-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) phosphorylates serine 221 leading to full p90S6K activation (45). Here, in IL-3-activated eosinophils, we detected all four phospho-sites initially targeted by ERK.

It does not appear that dynamic turnover of the α-chain of IL-3 and GM-CSF receptors are a contributing factor for the important consumption of IL-3, and the prolonged maintenance of p90S6K phosphorylation by IL-3-versus GM-CSF-or IL-5-activation of eosinophils. Indeed, we and others (46) did not detect down-modulation of GM-CSFRA following eosinophil activation with GM-CSF. In addition, there are incongruent effects of PI3K activation on receptor expression and RPS6 activation. Up-regulation of IL3RA by the βc receptor-signaling cytokines is reported to be PI3K-dependent (46), while we showed that RPS6 phosphorylation in IL-3-activated eosinophils was PI3K-independent. Also, decreased IL-3 receptor level and high consumption of IL-3 could reflect IL-3/IL-3 receptor internalization, which in turn can trigger a signal into the nucleus. The translocation of ligand/receptor complexes into the nucleus has been described for IFN-γ and IL-5 (47, 48). For instance, the IFN-γ/IFNGR/JAK/STAT complex can enter the nucleus where it stimulates the transcription of specific genes in a non-canonical way (47). However, the use of a neutralizing anti-IL-3 antibody indicates that the constant presence of IL-3 rather than a secondary signal accounts for sustained intracellular signaling in IL-3-activated eosinophils. Besides, a possible explanation for the GM-CSF-mediated attenuation of p90S6K and RPS6 phosphorylations is that GM-CSF triggers a negative feedback response on its own receptor by activating an accessory receptor carrying an immune-receptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) (49). Finally, the level of the common β-chain receptor could be downregulated by IL-3 compared to GM-CSF or IL-5. Yet, Gregory et al have previously shown that GM-CSF or IL-5 did not differentially change the β-chain receptor level compared to IL-3 1 h after activation (46). Nineteen hours after activation, however, the β-chain receptor level was lower in IL-3-activated eosinophils compared to GM-CSF or IL-5 (46), indicating that changes in the β-chain receptor level cannot account for the sustained signaling in IL-3-stimulated cells compared to GM-CSF-stimulated cells.

The function of RPS6 phosphorylation in non-dividing cells such as eosinophils and neutrophils is unexplored. RPS6 phosphorylation has been described in LPS-simulated neutrophils. RPS6 phosphorylation was p38 and ERK dependent (50); however, the possible function of p90S6K on RPS6, and translation regulation were not analyzed. Here, we showed that compared to GM-CSF, IL-3 prolonged p90S6K activity and significantly increased global translation by ~40% and the translation of semaphorin-7A by >10 fold. These data suggest that phosphorylation of RPS6 enhances protein synthesis from a subset of mRNAs stimulating their binding to the 40S ribosomal subunit. This has been previously suggested in proliferating cells where RPS6 activation mediates ribosome biogenesis (51). Also, Thomas et al demonstrated that cell activation significantly increased the translation of a group of unidentified transcripts independent of transcription (52). This mechanism allows rapid translation of pre-existing transcripts. It is noteworthy that semaphorin-7A mRNA is abundant in resting eosinophils (15) but modestly translated in the absence of IL-3 activation and prolonged RPS6 phosphorylation. Other ribosomal proteins such as RPL13a and RPL26 can enhance the translation of specific mRNAs (53, 54). RPS6 phospho-target mRNAs may be those with a pyrimidine consensus sequence in their 5′ UTR (TOP mRNAs) and coding for proteins implicated in translation (55). Because our data suggest that TOP mRNAs (PABP or EEF1A1) were not further translated in IL-3-versus GM-CSF-activated eosinophils, other features must also be involved in the selection of the group of mRNAs affected by p90S6K/RPS6 phosphorylation in IL-3-activated eosinophils. Analysis by gene-wide microarrays of polyribosomes could yield important information, but is technically challenging due to the meager recovery of polyribosome-associated RNA from eosinophils.

In addition to RPS6, eIF4B is a potential ribosomal p90S6K target (36). Phosphorylated eIF4B interacts with eIF3A, enhancing translation initiation (56). However, due to the fact that little or no phosphorylation of eIF4B in eosinophils was observed in vitro or in vivo, eIF4B is probably not responsible for the increased translation of semaphorin-7A. We cannot, however, rule out that eIF4B might be involved in the modest increase in global translation (~40%) in IL-3-compared to GM-CSF-activated eosinophils. P90S6K can also target transcription factors such as CREB and IκBα and thus increase transcription (57). However, inhibition of p90S6K activity had little effect on semaphorin-7A mRNA accumulation in IL-3-activated eosinophils.

We provide evidence that p90S6K and RPS6 are phosphorylated in vivo following airway allergen challenge of atopic individuals. Airway eosinophils lose most of their IL-5 receptors (11) suggesting that GM-CSF and IL-3 drive eosinophil function after eosinophils migrate to the airway. This is supported by our data showing activation of the p90S6K/RPS6 signaling in airway eosinophils does not require stimulation ex vivo. Since GM-CSF and IL-3 have synergistic functions on RPS6 phosphorylation in cultured blood eosinophils and both of these cytokines and their receptors are present in the airway (15, 20), it is reasonable to postulate that both cytokines participate in this signaling in airway eosinophils. Also, because we have recently shown that airway eosinophils express higher semaphorin-7A levels compared to blood eosinophils (14), we would also propose that p90S6K/RPS6 signaling increased semaphorin-7A translation in airway eosinophils (15). Even though the function of semaphorin-7A in eosinophils is largely unknown, it is pro-fibrotic in lung and liver (15, 58, 59). We found previously that IL-3-activated eosinophils adhere to plexin-C1 (15), which only known ligand is semaphorin-7A (60). Via an interaction with plexin-C1, semaphorin-7A could be involved in eosinophil migration as demonstrated for neutrophils (61). In addition, beyond semaphorin-7A, a potential translational increase of a variety of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors by eosinophils would have a strong immunomodulatory impact during an allergic disease (Reviewed in (62)).

In conclusion, our study shows important differences among the βc receptor-signaling cytokines regarding signaling in eosinophils. Through p90S6K, IL-3 has profound and distinctive effects on global and mRNA-specific translation. By enhancing p90S6K and RPS6 activity, IL-3 likely increases many proteins. Their identification is critical to appreciate the potential influence and value that blocking this pathway would have on eosinophil functions. Further studies characterizing both the underlying mechanisms as well as the regulated proteins may yield novel therapeutic opportunities to treat allergic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the subject volunteers who participated in this study, the staff of the Eosinophil Core facility for blood and airway eosinophil purification, our research nurse coordinators for subject recruitment and screening, and our pulmonologists for assistance with bronchoscopies. We thank Larissa DeLain for laboratory technical support and Mike Evans for the statistical analyses.

Abbreviations used in this article

- p90S6K

90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- eIF4B

eukaryotic translation initiation factor

- IL5RA

IL-5 receptor-α

- PP1

phosphatase 1

- RPS6

ribosomal protein S6

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Program Project Grant (NIH HL088594) and the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (NCRR/NIH 1UL1RR025011).

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Esnault S, Kelly EA, Nettenstrom LM, Cook EB, Seroogy CM, Jarjour NN. Human Eosinophils Release Il-1β and Increase Expression of Il-17a in Activated Cd4(+) T Lymphocytes. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1756–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travers J, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophils in Mucosal Immune Responses. Mucosal immunology. 2015;8:464–475. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broekema M, Volbeda F, Timens W, Dijkstra A, Lee NA, Lee JJ, Lodewijk ME, Postma DS, Hylkema MN, Ten Hacken NH. Airway Eosinophilia in Remission and Progression of Asthma: Accumulation with a Fast Decline of Fev(1) Respir Med. 2010;104:1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humbles AA, Lloyd CM, McMillan SJ, Friend DS, Xanthou G, McKenna EE, Ghiran S, Gerard NP, Yu C, Orkin SH, Gerard C. A Critical Role for Eosinophils in Allergic Airways Remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1776–1779. doi: 10.1126/science.1100283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JJ, Dimina D, Macias MP, Ochkur SI, McGarry MP, O’Neill KR, Protheroe C, Pero R, Nguyen T, Cormier SA, Lenkiewicz E, Colbert D, Rinaldi L, Ackerman SJ, Irvin CG, Lee NA. Defining a Link with Asthma in Mice Congenitally Deficient in Eosinophils. Science. 2004;305:1773–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.1099472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilvering B, Xue L, Pavord ID. Evidence for the Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Interleukin-5 Treatment in the Management of Refractory Eosinophilic Asthma. Therapeutic advances in respiratory disease. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1753465815581279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flood-Page PT, Menzies-Gow AN, Kay AB, Robinson DS. Eosinophil’s Role Remains Uncertain as Anti-Interleukin-5 Only Partially Depletes Numbers in Asthmatic Airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:199–204. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-789OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, Gupta S, Monteiro W, Sousa A, Marshall RP, Bradding P, Green RH, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Mepolizumab and Exacerbations of Refractory Eosinophilic Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:973–984. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, Inman MD, Efthimiadis A, Pizzichini E, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne PM. Mepolizumab for Prednisone-Dependent Asthma with Sputum Eosinophilia. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:985–993. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flood-Page P, Swenson C, Faiferman I, Matthews J, Williams M, Brannick L, Robinson D, Wenzel S, Busse W, Hansel TT, Barnes NC. A Study to Evaluate Safety and Efficacy of Mepolizumab in Patients with Moderate Persistent Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1062–1071. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-085OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu LY, Sedgwick JB, Bates ME, Vrtis RF, Gern JE, Kita H, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Kelly EAB. Decreased Expression of Membrane Il-5r Alpha on Human Eosinophils: I. Loss of Membrane Il-5 Alpha on Eosinophils and Increased Soluble Il-5r Alpha in the Airway after Antigen Challenge. J Immunol. 2002;169:6452–6458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson MW, Gunderson KA, Kelly EA, Denlinger LC, Jarjour NN, Mosher DF. Anti-Il-5 Attenuates Activation and Surface Density of Beta(2) -Integrins on Circulating Eosinophils after Segmental Antigen Challenge. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munitz A, Bachelet I, Eliashar R, Khodoun M, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME, Levi-Schaffer F. Cd48 Is an Allergen and Il-3-Induced Activation Molecule on Eosinophils. J Immunol. 2006;177:77–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly EA, Liu LY, Esnault S, Quinchia-Rios BH, Jarjour NN. Potent Synergistic Effect of Il-3 and Tnf on Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Generation by Human Eosinophils. Cytokine. 2012;58:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esnault S, Kelly EA, Johansson MW, Liu LY, Han SH, Akhtar M, Sandbo N, Mosher DF, Denlinger LC, Mathur SK, Malter JS, Jarjour NN. Semaphorin 7a Is Expressed on Airway Eosinophils and Upregulated by Il-5 Family Cytokines. Clin Immunol. 2014;150:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder JT, Chichester KL, Bieneman AP. Human Basophils Secrete Il-3: Evidence of Autocrine Priming for Phenotypic and Functional Responses in Allergic Disease. J Immunol. 2009;182:2432–2438. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnsson M, Bove M, Bergquist H, Olsson M, Fornwall S, Hassel K, Wold AE, Wenneras C. Distinctive Blood Eosinophilic Phenotypes and Cytokine Patterns in Eosinophilic Esophagitis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Airway Allergy. Journal of innate immunity. 2011;3:594–604. doi: 10.1159/000331326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patil SP, Wisnivesky JP, Busse PJ, Halm EA, Li XM. Detection of Immunological Biomarkers Correlated with Asthma Control and Quality of Life Measurements in Sera from Chronic Asthmatic Patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson DS, Ying S, Bentley AM, Meng Q, North J, Durham SR, Kay AB, Hamid Q. Relationships among Numbers of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cells Expressing Messenger Ribonucleic Acid for Cytokines, Asthma Symptoms, and Airway Methacholine Responsiveness in Atopic Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:397–403. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson MW, Kelly EA, Busse WW, Jarjour NN, Mosher DF. Up-Regulation and Activation of Eosinophil Integrins in Blood and Airway after Segmental Lung Antigen Challenge. J Immunol. 2008;180:7622–7635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas G, Martin-Perez J, Siegmann M, Otto AM. The Effect of Serum, Egf, Pgf2 Alpha and Insulin on S6 Phosphorylation and the Initiation of Protein and DNA Synthesis. Cell. 1982;30:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans SW, Farrar WL. Interleukin 2 and Diacylglycerol Stimulate Phosphorylation of 40 S Ribosomal S6 Protein. Correlation with Increased Protein Synthesis and S6 Kinase Activation. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4624–4630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, Blenis J. Rapamycin-Fkbp Specifically Blocks Growth-Dependent Activation of and Signaling by the 70 Kd S6 Protein Kinases. Cell. 1992;69:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90643-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruvinsky I, Sharon N, Lerer T, Cohen H, Stolovich-Rain M, Nir T, Dor Y, Zisman P, Meyuhas O. Ribosomal Protein S6 Phosphorylation Is a Determinant of Cell Size and Glucose Homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2199–2211. doi: 10.1101/gad.351605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan R, McConkey EH. Preferential Utilization of Phosphorylated 40-S Ribosomal Subunits During Initiation Complex Formation. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS. 1982;123:535–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nygard O, Nika H. Identification by Rna-Protein Cross-Linking of Ribosomal Proteins Located at the Interface between the Small and the Large Subunits of Mammalian Ribosomes. EMBO J. 1982;1:357–362. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandi HR, Ferrari S, Krieg J, Meyer HE, Thomas G. Identification of 40 S Ribosomal Protein S6 Phosphorylation Sites in Swiss Mouse 3t3 Fibroblasts Stimulated with Serum. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4530–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalaileh A, Dreazen A, Khatib A, Apel R, Swisa A, Kidess-Bassir N, Maitra A, Meyuhas O, Dor Y, Zamir G. Phosphorylation of Ribosomal Protein S6 Attenuates DNA Damage and Tumor Suppression During Development of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1811–1820. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly EA, Rodriguez RR, Busse WW, Jarjour NN. The Effect of Segmental Bronchoprovocation with Allergen on Airway Lymphocyte Function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1421–1428. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.9703054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. A Practical Guide to Evaluating Colocalization in Biological Microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C723–742. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu LY, Sedgwick JB, Bates ME, Vrtis RF, Gern JE, Kita H, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Kelly EAB. Decreased Expression of Membrane Il-5r Alpha on Human Eosinophils: Ii. Il-5 Down-Modulates Its Receptor Via a Proteinase-Mediated Process. J Immunol. 2002;169:6459–6466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roux PP, Shahbazian D, Vu H, Holz MK, Cohen MS, Taunton J, Sonenberg N, Blenis J. Ras/Erk Signaling Promotes Site-Specific Ribosomal Protein S6 Phosphorylation Via Rsk and Stimulates Cap-Dependent Translation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14056–14064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erikson E, Maller JL. A Protein Kinase from Xenopus Eggs Specific for Ribosomal Protein S6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:742–746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen RH, Sarnecki C, Blenis J. Nuclear Localization and Regulation of Erk- and Rsk-Encoded Protein Kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:915–927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaru R, Ronkina N, Gaestel M, Arthur JS, Watts C. The Mapk-Activated Kinase Rsk Controls an Acute Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Response in Dendritic Cells and Is Activated through Two Distinct Pathways. Nature immunology. 2007;8:1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/ni1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shahbazian D, Roux PP, Mieulet V, Cohen MS, Raught B, Taunton J, Hershey JW, Blenis J, Pende M, Sonenberg N. The Mtor/Pi3k and Mapk Pathways Converge on Eif4b to Control Its Phosphorylation and Activity. EMBO J. 2006;25:2781–2791. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyuhas O. Physiological Roles of Ribosomal Protein S6: One of Its Kind. International review of cell and molecular biology. 2008;268:1–37. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)00801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chauvin C, Koka V, Nouschi A, Mieulet V, Hoareau-Aveilla C, Dreazen A, Cagnard N, Carpentier W, Kiss T, Meyuhas O, Pende M. Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase Activity Controls the Ribosome Biogenesis Transcriptional Program. Oncogene. 2014;33:474–483. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen ZJ, Esnault S, Rosenthal LA, Szakaly RJ, Sorkness RL, Westmark PR, Sandor M, Malter JS. Pin1 Regulates Tgf-Beta1 Production by Activated Human and Murine Eosinophils and Contributes to Allergic Lung Fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:479–490. doi: 10.1172/JCI32789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiang CW, Harris G, Ellig C, Masters SC, Subramanian R, Shenolikar S, Wadzinski BE, Yang E. Protein Phosphatase 2a Activates the Proapoptotic Function of Bad in Interleukin-3-Dependent Lymphoid Cells by a Mechanism Requiring 14-3-3 Dissociation. Blood. 2001;97:1289–1297. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutchinson JA, Shanware NP, Chang H, Tibbetts RS. Regulation of Ribosomal Protein S6 Phosphorylation by Casein Kinase 1 and Protein Phosphatase 1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8688–8696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erikson E, Maller JL. Substrate Specificity of Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase Ii from Xenopus Eggs. Second messengers and phosphoproteins. 1988;12:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lara R, Seckl MJ, Pardo OE. The P90 Rsk Family Members: Common Functions and Isoform Specificity. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5301–5308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angenstein F, Greenough WT, Weiler IJ. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor-Initiated Translocation of Protein Kinase P90rsk to Polyribosomes: A Possible Factor Regulating Synaptic Protein Synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen CJ, Buch MB, Krag TO, Hemmings BA, Gammeltoft S, Frodin M. 90-Kda Ribosomal S6 Kinase Is Phosphorylated and Activated by 3-Phosphoinositide-Dependent Protein Kinase-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27168–27176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gregory B, Kirchem A, Phipps S, Gevaert P, Pridgeon C, Rankin SM, Robinson DS. Differential Regulation of Human Eosinophil Il-3, Il-5, and Gm-Csf Receptor Alpha-Chain Expression by Cytokines: Il-3, Il-5, and Gm-Csf Down-Regulate Il-5 Receptor Alpha Expression with Loss of Il-5 Responsiveness, but up-Regulate Il-3 Receptor Alpha Expression. J Immunol. 2003;170:5359–5366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noon-Song EN, Ahmed CM, Dabelic R, Canton J, Johnson HM. Controlling Nuclear Jaks and Stats for Specific Gene Activation by Ifngamma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;410:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jans DA, Briggs LJ, Gustin SE, Jans P, Ford S, Young IG. The Cytokine Interleukin-5 (Il-5) Effects Cotransport of Its Receptor Subunits to the Nucleus in Vitro. FEBS Letters. 2000;410:368–372. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munitz A, Bachelet I, Eliashar R, Moretta A, Moretta L, Levi-Schaffer F. The Inhibitory Receptor Irp60 (Cd300a) Suppresses the Effects of Il-5, Gm-Csf, and Eotaxin on Human Peripheral Blood Eosinophils. Blood. 2006;107:1996–2003. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cloutier A, Ear T, Blais-Charron E, Dubois CM, McDonald PP. Differential Involvement of Nf-Kappab and Map Kinase Pathways in the Generation of Inflammatory Cytokines by Human Neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:567–577. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas G. An Encore for Ribosome Biogenesis in the Control of Cell Proliferation. Nature cell biology. 2000;2:E71–72. doi: 10.1038/35010581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas G, Thomas G, Luther H. Transcriptional and Translational Control of Cytoplasmic Proteins after Serum Stimulation of Quiescent Swiss 3t3 Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:5712–5716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazumder B, Sampath P, Seshadri V, Maitra RK, DiCorleto PE, Fox PL. Regulated Release of L13a from the 60s Ribosomal Subunit as a Mechanism of Transcript-Specific Translational Control. Cell. 2003;115:187–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takagi M, Absalon MJ, McLure KG, Kastan MB. Regulation of P53 Translation and Induction after DNA Damage by Ribosomal Protein L26 and Nucleolin. Cell. 2005;123:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jefferies HB, Reinhard C, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Rapamycin Selectively Represses Translation of the “Polypyrimidine Tract” Mrna Family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4441–4445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Mtor and S6k1 Mediate Assembly of the Translation Preinitiation Complex through Dynamic Protein Interchange and Ordered Phosphorylation Events. Cell. 2005;123:569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frodin M, Gammeltoft S. Role and Regulation of 90 Kda Ribosomal S6 Kinase (Rsk) in Signal Transduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;151:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Minicis S, Rychlicki C, Agostinelli L, Saccomanno S, Trozzi L, Candelaresi C, Bataller R, Millan C, Brenner DA, Vivarelli M, Mocchegiani F, Marzioni M, Benedetti A, Svegliati-Baroni G. Semaphorin 7a Contributes to Tgf-Beta-Mediated Liver Fibrogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang HR, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Elias JA. Semaphorin 7a Plays a Critical Role in Tgf-Beta1-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1083–1093. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamagnone L, Artigiani S, Chen H, He Z, Ming GI, Song H, Chedotal A, Winberg ML, Goodman CS, Poo M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Comoglio PM. Plexins Are a Large Family of Receptors for Transmembrane, Secreted, and Gpi-Anchored Semaphorins in Vertebrates. Cell. 1999;99:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granja T, Kohler D, Mirakaj V, Nelson E, Konig K, Rosenberger P. Crucial Role of Plexin C1 for Pulmonary Inflammation and Survival During Lung Injury. Mucosal immunology. 2014;7:879–891. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davoine F, Lacy P. Eosinophil Cytokines, Chemokines, and Growth Factors: Emerging Roles in Immunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:570. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.