Abstract

Dementia incidence increases exponentially with age even in people aged 90 years and older. Because therapeutic regimens are limited, modification of lifestyle behaviors may offer the best means for disease control. To test the hypotheses that lifestyle factors are related to lower risk of dementia in the oldest-old, we analyzed data from The 90+ Study, a population-based longitudinal cohort study initiated in 2003. This analysis included 587 participants (mean age = 93 years) seen in-person and determined not to have dementia at enrollment. Information on lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, caffeine intake, vitamin supplement use, exercise and other activities) was obtained at enrollment and was available from data collected 20 years previously. After an average follow-up of 36 months, 268 participants were identified with incident dementia. No variable measured 20 years previously was associated with risk. Engagement in specific activities at time of enrollment, especially going to church/ synagogue and reading, was associated with significantly reduced risk. Consumers of 200+ mg/day of caffeine had a 34 per cent lower risk (HR=0.66, p<0.05) compared with those consuming <50 mg/day. Users of antioxidant vitamin supplements had 25 per cent lower risks compared with non-users. With reading, going to church, caffeine, and vitamin C supplements analyzed together, the HRs changed little and remained significant for reading (0.54, p=0.01) and going to church (HR=0.66, p<0.05) but were not significant for caffeine (HR=0.61, p=0.15) and vitamin C (HR= 0.68, p=0.07). This analysis suggests that lifestyle behaviors at approximately age 70 do not modify risk of late-life dementia. However, participation in activities and caffeine and supplemental vitamin intake around age 90 may reduce risk of dementia in the oldest-old, although cause and effect cannot be determined.

Introduction

Dementia incidence increases exponentially with age doubling approximately every 5 years after age 65 even in people aged 90 years and older.1,2 Projections of the number of people with dementia from these incidence rates foretell the growing public health burden of dementia in an increasingly aging population.

Because therapeutic regimens are limited, modification of lifestyle behaviors may offer the only means for disease control. Several lifestyle behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, vitamin intake, physical and other activities) have been found to be associated with future development of dementia in older adults,3,4 but whether or not lifestyle factors are related to dementia incidence after age 90 – the oldest-old – is not known. Therefore we examined the association of several lifestyle practices on incident dementia in a longitudinal study of the oldest-old.

Methods

Study Population

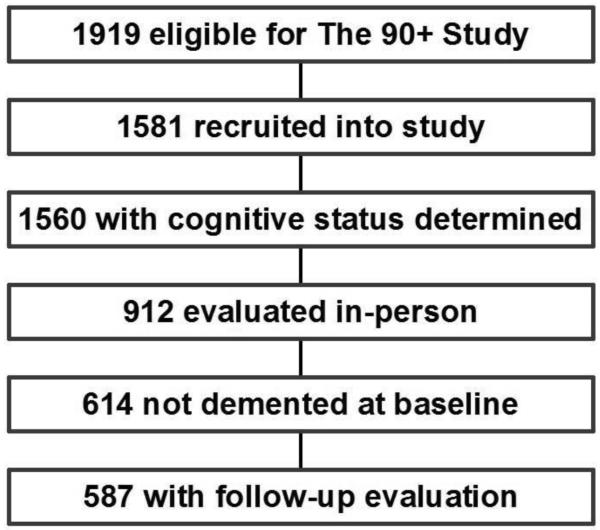

Participants were part of The 90+ Study, a population-based longitudinal study of aging and dementia among people aged 90 years and older.2,5 These subjects were originally members of the Leisure World Cohort Study, an epidemiological health study established in the early 1980s of a California retirement community, Leisure World Laguna Hills.6,7 Individuals alive and aged 90 years and older on January 1, 2003 (n=1144); on January 1, 2008 (n=443); and on or after January 1, 2009 (n=335) were invited to participate. Of the 1919 eligible cohort members, 1581 joined The 90+ Study. We restricted our analysis to the 587 participants who did not have dementia at baseline, as ascertained by an in-person evaluation, and who had at least one additional follow-up evaluation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selection of the 587 participants included in the analysis of lifestyle factors and risk of incident dementia

Assessments

Participants were asked to undergo an in-person evaluation including a neurological examination (with mental status testing and assessment of functional abilities) by a trained physician or nurse practitioner and a neuropsychological test battery8 that included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).9 For participants whose poor health, frailty, disability, or unwillingness did not allow a full in-person evaluation, information was obtained by telephone or with informants. Participants evaluated by telephone completed the short version of the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI-short).10 For participants evaluated through informants, the Dementia Questionnaire (DQ)11–13 was completed over the telephone. All participants (or their informants) completed a questionnaire that included demographics, past medical history, and medication use. In addition, informants of all participants were asked about the participant’s cognitive status14 and functional abilities15,16 using a mailed questionnaire. Evaluations were repeated every 6 months for in-person participants and annually for participants evaluated by telephone and through informants. The DQ was also completed for all participants shortly after death.

Determination of Cognitive Status

For all participants included in these analyses cognitive status at baseline was determined from an in-person evaluation. Cognitive status at follow-up was also determined from an in-person evaluation for most participants (70%). However, when an in-person evaluation at follow-up was not possible, we used any available information in the following hierarchical order: (1) neurological exam, (2) MMSE, (3) informant questionnaires, and (4) CASI-short. The neurological examiner determined cognitive status applying Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria for dementia17. For the MMSE, we used age- and education-specific cutoff scores for dementia derived from this cohort.18 For the CASI-short, we used a score ≤25 as the cutoff score for dementia.10 Details about the application of the algorithms and the validity of these methods are published elsewhere.2,5

Lifestyle Behaviors

Questions on lifestyle behaviors were asked twice: on the original Leisure World Cohort health survey (1981-1985) and repeated at the baseline visit of The 90+ Study (2003-2014).

Smoking

Participants were asked “Have you ever smoked cigarettes during any period of your life (aside from possibly trying them once or twice)?”, the greatest number of cigarettes regularly smoked (¼ pack per day, ½ pack per day, 1 pack per day, 1½ packs per day, 2 packs per day or more), age started smoking regularly, and age stopped smoking.

Alcohol Consumption

Consumption of alcoholic beverages was asked separately for wine (4 oz.), beer (12 oz.), and hard liquor (1 oz.), each equivalent to about ½ oz. of alcohol. Response choices for average weekday consumption were: never drink, <1, 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more. Total alcohol intake per day was calculated by summing the number of drinks consumed of each type.

Caffeine Intake

Participants were asked “How many cups or glasses per DAY do you drink of the following — milk, decaffeinated coffee, coffee, black or green tea?” and “How many cans or glasses per WEEK do you drink of the following —cola beverages with sugar, other soft drinks with sugar, cola beverages artificially sweetened, other soft drinks artificially sweetened?” Response choices were none, <1, 1, 2–3, 4–5, and 6+. Also asked was intake of “CHOCOLATE (milk chocolate, fudge, M&M’s, Tootsie Rolls, chocolate covered centers, chocolate topping, chocolate cake, chocolate pie, hot chocolate, chocolate milk)”. Response choices were rarely or never, a few times per year, about monthly, a few times a month, a few times per week, daily or almost daily. The 90+ Study asked separately about decaffeinated tea and regular tea and decaffeinated and caffeinated soft drinks. We estimated daily caffeine intake by summing the frequency of consumption of each beverage and chocolate multiplied by its average caffeine content (milligrams/standard unit) as 115 for regular coffee, 3 for decaffeinated coffee, 50 for regular tea, 3 for decaffeinated tea, 50 for cola or caffeinated soft drinks, and 6 for chocolate.19

Vitamin Supplements

The Leisure World Cohort survey included questions on current use of vitamin supplements in general and specific intake including dose of vitamins A, C and E (multivitamins and individual vitamins). The 90+ Study asked vitamin supplement intake as well, with dose identified from the individual vitamin containers when possible.

Exercise and Other Activities

The amount of time spent on physical activities was ascertained by asking, “On the average weekday, how much time do you spend in the following activities? —Active outdoor activities (e.g., swimming, biking, jogging, tennis, vigorous walking) —Active indoor activities (e.g., exercising, dancing) —Other outdoor activities (e.g., sightseeing, boating, fishing, golf, gardening, attending sporting events) —Other indoor activities (e.g., reading, sewing, crafts, board games, pool, attending theater or concerts, performing household chores) —Watching TV.” For each question, the response categories were 0, 15, 30 minutes, 1, 2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, 9 hours or more per day. The time spent per day in active activities was calculated by summing the times spent in active outdoor and active indoor activities; in other less physically demanding activities by summing the times spent in other outdoor and other indoor activities.

Additional exercise questions were asked on follow-up questionnaires sent to Leisure World Cohort members in 1983, 1985 and 1998. These asked hours/day spent in vigorous exercise in 1983 and 1998 and whether the participant engaged in moderate or vigorous exercise at age 40.

The 90+ Study also asked participants the time spent (daily or almost daily, a few times per week, a few times per month, about monthly, a few times per year, rarely or never) in the following 16 activities: being outside, going on walks, enjoying nature; being with animals; getting together with family and friends; talking to family and friends on the telephone; going to movies, museums, entertainment; going to church, synagogue, religious events; going shopping for groceries, clothes, etc.; going for a ride in the car; reading or having stories read to you; listening to radio, watching TV; doing vigorous exercise; playing games or cards, doing crosswords, puzzles; doing handiwork or crafts; gardening, indoor or outdoor; traveling with at least one overnight stay; sitting and thinking.

Statistical Analyses

Hazard ratios (HRs) of dementia associated with lifestyle factors as measured by the Leisure World Cohort Study and by The 90+ Study were estimated using Cox regression analysis.20 Age at study entry was the age at enrollment in The 90+ Study (delayed entry) and the event of interest was age at dementia diagnosis. Given our model used delayed entry (analogous to specifying time-dependent variables), the Cox regression is no longer a proportional hazard model. HRs for each lifestyle variable were adjusted for age using age (continuous) as the fundamental time scale and for sex and education (≤ high school, vocational school or some college, college graduate) by including them as covariates in the model. Participants were followed until age of dementia diagnosis, death or last visit, whichever came first. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Separate analyses were done for each lifestyle factor and no adjustment in the p-values was made for multiple comparisons.

Results

At baseline, the participants’ ages ranged from 90 to 103 years (mean ± standard deviation = 93 ± 2.6). By the end of followup, which averaged 36 months, 268 participants had been diagnosed with dementia at ages 90 to 106 (mean ± standard deviation = 96 ± 3.0).

Table 1 shows the age-, sex- and education-adjusted HRs of incident dementia for lifestyle factors collected at enrollment in The 90+ Study (in 2003 or later) and by the Leisure World Cohort Study about 20 years previously (in the early 1980s). Few lifestyle factors either at baseline or 20 years previously were associated with risk of incident dementia. Neither smoking, alcohol consumption, caffeine intake or antioxidant vitamin supplement use as reported in the 1980s was related to risk. Neither was active or other exercise in the 1980s nor vigorous exercise in 1983, in 1998, or at age 40. Those reporting intake of 200+ mg/day of caffeine at enrollment in The 90+ Study had a significantly lower risk of dementia (HR=0.66, 95% CI 0.43-0.99) compared with those with intake of <50 mg/day. Users of vitamin A, C or E supplements had significantly lower risks (about 25 per cent) compared with non-users. When all The 90+ Study variables in Table 1 were included in the regression model, the HRs for caffeine were reduced to 0.67 (95% CI 0.41-1.08) for 50-199 mg/day and 0.60 (95% CI 0.33-1.09) for 200+ mg/day. The HR for vitamin C supplement users was reduced to 0.53 (95% CI 0.22-1.26).

TABLE 1.

Hazard ratios for incident dementia by lifestyle behaviors at enrollment in The 90+ Study and 20 years previously in the Leisure World Cohort Study

| At enrollment in The 90+ Study (2003 or later) |

By the Leisure World Cohort Study (1980s) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle Behavior | No.† | No. with incident dementia |

HR‡ | 95% CI | No.† | No. with incident dementia |

HR‡ | 95% CI |

| Smoke | ||||||||

| Never | 294 | 135 | 1.00 | 274 | 132 | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 271 | 119 | 0.95 | 0.74-1.21 | 313 | 136 | 0.84 | 0.66-1.07 |

| <1 packs/day | 156 | 70 | 0.95 | 0.71-1.28 | 160 | 71 | 0.80 | 0.60-1.07 |

| 1+ packs/day | 99 | 39 | 0.89 | 0.62-1.27 | 144 | 61 | 0.90 | 0.66-1.22 |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/day) | ||||||||

| 0 | 208 | 87 | 1.00 | 112 | 49 | 1.00 | ||

| <2 | 260 | 118 | 0.97 | 0.73-1.28 | 291 | 135 | 1.00 | 0.72-1.39 |

| 2+ | 79 | 41 | 1.09 | 0.75-1.58 | 184 | 84 | 1.03 | 0.72-1.46 |

| Caffeine intake (mg/day) | ||||||||

| <50 | 104 | 52 | 1.00 | 147 | 61 | 1.00 | ||

| 50-199 | 137 | 61 | 0.76 | 0.52-1.10 | 221 | 102 | 0.96 | 0.70-1.32 |

| 200+ | 97 | 41 | 0.66 | 0.43-0.99 | 219 | 105 | 1.04 | 0.76-1.43 |

| Vitamin A supplements | ||||||||

| No | 348 | 164 | 1.00 | 304 | 144 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 239 | 104 | 0.77 | 0.60-0.98 | 283 | 124 | 0.90 | 0.71-1.15 |

| Vitamin C supplements | ||||||||

| No | 292 | 139 | 1.00 | 210 | 100 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 295 | 129 | 0.74 | 0.58-0.94 | 377 | 168 | 0.92 | 0.72-1.19 |

| Vitamin E supplements | ||||||||

| No | 294 | 137 | 1.00 | 260 | 126 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 293 | 131 | 0.74 | 0.58-0.95 | 327 | 142 | 0.86 | 0.67-1.10 |

| Active exercise (hours/day) | ||||||||

| 0 | 110 | 43 | 1.00 | 128 | 48 | 1.00 | ||

| <1 | 65 | 19 | 0.68 | 0.40-1.17 | 176 | 90 | 1.27 | 0.89-1.80 |

| 1+ | 67 | 25 | 0.80 | 0.49-1.32 | 282 | 130 | 1.16 | 0.83-1.62 |

| DK | 345 | 181 | 0.91 | 0.64-1.29 | ||||

| Other exercise (hours/day) | ||||||||

| <3 | 120 | 46 | 1.00 | 147 | 63 | 1.00 | ||

| 3-4 | 69 | 26 | 0.89 | 0.54-1.44 | 194 | 88 | 1.03 | 0.74-1.43 |

| 5+ | 52 | 15 | 0.69 | 0.39-1.24 | 244 | 117 | 1.15 | 0.84-1.57 |

| DK | 346 | 181 | 0.94 | 0.67-1.32 | ||||

| Vigorous exercise at age 40 | ||||||||

| No | 275 | 128 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 175 | 79 | 1.12 | 0.84-1.50 | ||||

| Vigorous exercise in 1983 (hours/day) | ||||||||

| ≤1 | 145 | 70 | 1.00 | |||||

| 2+ | 198 | 91 | 0.81 | 0.58-1.12 | ||||

| Vigorous exercise in 1998 (hours/day) | ||||||||

| ≤1 | 137 | 54 | 1.00 | |||||

| 2+ | 144 | 63 | 1.22 | 0.83-1.78 | ||||

Numbers do not always total 587 due to subjects with missing values.

Adjusted for age by using age (continuous) as the time scale and for sex and education (≤ high school, vocational school or some college, college graduate) by including as covariates in the model.

DK = Don’t know; included as a separate category due to the large number with missing values.

Table 2 shows the HRs for specific activities reported at enrollment in The 90+ Study. Six of the 16 activities showed significantly reduced risk in participants. These HRs were 0.53 for shopping for groceries, clothes, etc.; 0.63 for going to movies, museums, entertainment; 0.66 for doing handiworks or crafts; 0.67 for being with animals; 0.71 for going for a ride in the car; and 0.74 for reading or having stories read. In a multivariate analysis including all the activity variables in Table 2, no activity showed a statistically reduced risk of dementia but reading and going to church/synagogue had HRs of 0.68 (p=0.09) and 0.66 (p=0.11).

TABLE 2.

Hazard ratios for incident dementia by activities reported at enrollment in The 90+ Study

| Activity / frequency | No.† | No. with incident dementia |

HR‡ | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being outside, going for walks, enjoying nature | ||||

| < Daily | 269 | 104 | 1.00 | |

| Daily | 248 | 119 | 1.01 | 0.78-1.32 |

| Being with animals | ||||

| Rarely/never | 328 | 156 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 176 | 62 | 0.67 | 0.50-0.90 |

| Getting together with family and friends | ||||

| <= few times/month | 198 | 90 | 1.00 | |

| >= few times/week | 319 | 134 | 0.92 | 0.70-1.21 |

| Talking to family and friends on the phone | ||||

| <= few times/month | 291 | 125 | 1.00 | |

| >= few times/week | 225 | 98 | 1.06 | 0.81-1.38 |

| Going to movies, museums, entertainment | ||||

| Rarely/never | 202 | 100 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 315 | 122 | 0.63 | 0.48-0.82 |

| Going to church, synagogue, religious events | ||||

| Rarely/never | 254 | 110 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 259 | 112 | 0.87 | 0.67-1.14 |

| Shopping for groceries, clothes, etc. | ||||

| <= Monthly | 132 | 68 | 1.00 | |

| >= few times/month | 387 | 155 | 0.53 | 0.39-0.70 |

| Going for a ride in the car | ||||

| <= Monthly | 145 | 75 | 1.00 | |

| >= few times/month | 365 | 143 | 0.71 | 0.53-0.94 |

| Reading or having stories read | ||||

| < Daily | 119 | 60 | 1.00 | |

| Daily | 397 | 165 | 0.74 | 0.54-0.99 |

| Watching TV or listening to radio | ||||

| < Daily | 30 | 15 | 1.00 | |

| Daily | 497 | 214 | 0.62 | 0.36-1.06 |

| Doing vigorous exercise | ||||

| Rarely/never | 265 | 106 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 247 | 113 | 0.88 | 0.67-1.16 |

| Playing games or cards, doing crosswords, puzzles | ||||

| Rarely/never | 371 | 169 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 150 | 55 | 0.78 | 0.57-1.05 |

| Doing handiwork or crafts | ||||

| Rarely/never | 351 | 152 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 75 | 31 | 0.66 | 0.44-0.97 |

| Gardening | ||||

| Rarely/never | 474 | 205 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 39 | 14 | 0.76 | 0.44-1.31 |

| Traveling with at least one overnight stay | ||||

| Rarely/never | 300 | 130 | 1.00 | |

| More frequently | 213 | 91 | 0.82 | 0.63-1.08 |

| Sitting and thinking | ||||

| < Daily | 157 | 64 | 1.00 | |

| Daily | 354 | 156 | 0.91 | 0.68-1.22 |

Numbers do not always total 587 due to subjects with missing values.

Adjusted for age by using age (continuous) as the time scale and for sex and education (≤ high school, vocational school or some college, college graduate) by including as covariates in the model.

When caffeine consumption, supplemental vitamin C intake, going to church/synagogue, and reading were considered jointly in a multivariate model, the HRs changed little: 0.61 for high caffeine intake (p=0.15), 0.68 for vitamin C use (p=0.07), 0.66 for going to church/synagogue (p<0.05), and 0.54 for reading (p=0.01).

Discussion

Our longitudinal study in the oldest-old found that few lifestyle factors, either at baseline or 20 years previously, were associated with risk of incident dementia. Only caffeine consumption, supplemental vitamin C intake and selected leisure activities reported at enrollment in The 90+ Study were related to reduced risk.

Leisure activities including those with mental, social and physical components have been related with reduced risk of dementia21-24 although recent reports have concluded the evidence is insufficient.25 Our study suggests that continued mental/social activity into the tenth decade of life is associated with a lower risk. However, we found no effect of active or other less physically demanding physical exercise. A recent review identified seven prospective studies of individuals aged 65+ years which evaluated the association between physical activity and dementia.26 Although all found some association of physical activity with reduced risk of dementia, no study included the very old.27-33 In our study specific activities associated with lower risk were shopping for groceries, clothes, etc.; doing handiworks or crafts; reading or having stories read; being with animals; going to movies, museums, entertainment; and going for a ride in the car. In joint analysis reading and going to church/synagogue were the most significant. These activities have a strong mental component. However, reduced activity level at time of enrollment in The 90+ Study may reflect less participation by individuals showing early cognitive deficits and not a real risk reduction.

Our study, which found that consumers of 200+ mg/day of caffeine had a 40% reduced risk of incident dementia, supports previous findings of decreased risk among caffeine or coffee consumers.34,35 In the prospective CSHA (Canadian Study of Health and Aging) of healthy older (>65 years) adults, regular daily coffee drinking was associated with a 30% lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) over five years.36 The CAIDE (Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Dementia) study found that moderate coffee drinkers (3-5 cups/day) at midlife had a 65 per cent lower risk of dementia later in life compared with those drinking no or only little coffee.37 A small case-control study of 54 older adults with probable AD and age-matched healthy controls reported a strong inverse correlation of caffeine intake and AD risk; intake of 200 mg/day lowered risk by 60% vs. 70 mg/day.38 Finally, recent prospective data indicated that high plasma caffeine levels were associated with a reduced risk of dementia or a delayed onset in patients with mild cognitive impairment.39 Although the Honolulu–Asian Aging Study did not find a significant association between caffeine intake and dementia risk, autopsy patients in the highest quartile of caffeine intake (>277.5 mg/day) were less likely to have neuropathological lesions, such as AD-related lesions, microvascular ischemic lesions, cortical Lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis, or generalized atrophy.40 Caffeine is a central nervous system stimulant, has antioxidant properties, may prevent neuronal cell death caused by exposure to β-amyloid, and has shown neuroprotective effects after administration in experimental models of the cerebral nervous hypoxia and ischemia, suggesting plausible biological mechanisms.34,35 Although caffeine is the most widely consumed behaviorally active substance in the western world and despite epidemiological data on the effects of caffeine in aged subjects and data from animal studies, no clinical trial has examined the extent by which caffeine can reduce disease incidence or slow down progression.

Longitudinal studies have identified significantly increased risks of dementia among tobacco smokers41,42 and, though less consistently, decreased risks among moderate drinkers of alcohol.43 These were not associated with dementia risk in our study. Our study population included very few current smokers; only 5 participants were current smokers when they enrolled in The 90+ Study and only 36 in the early 1980s so we could not examine risk in only current smokers. No elevated risk was observed in ever smokers.

Some prospective studies have reported that intake of anti-oxidants are associated with reduced risk of dementia. People with higher intakes of vitamin E and C, either through diet or supplements, have been found to have slower cognitive decline and a lower risk of AD in old age [reviewed in reference 44]. However, other large, prospective observational studies found no association between vitamin intake and dementia risk. Likewise, evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials is at best inconsistent, with most studies finding no relationship between vitamin E supplementation and cognitive performance.44,45 In our study of the oldest-old we found supplemental intake of vitamins A, C or E. taken at enrollment in the 90+ Study, but not in the 1980s, was associated with lower dementia risk. As previously reported, more than 90% of the Leisure World Cohort members received the 1980 recommended dietary allowance of the National Research Council for vitamin A (5000 IU for males; 4000 IU for females) from food sources alone.46 Therefore non-users of supplements were unlikely to have low levels of these antioxidants. We cannot rule out the possibility that long-term antioxidant supplementation may reduce the risk of incident dementia in other populations with lower levels of vitamin intake.

Our study has several limitations and strengths that warrant discussion. Our subjects are from a select population — moderately affluent, highly educated, health conscious, and primarily Caucasian. Although this may limit the generalizability of our results, it reduces potential confounding by race, education, SES, and access to health care. The independent variables used in these analyses are crude and self-reported and their reliability and validity were not ascertained. Although changes over time in potential risk factors may affect outcome, lifestyle practices are, like all habits, routines of behavior that are repeated regularly and become customary and we had data at two time points – at enrollment and about 20 years previously. Like most studies reporting on the association of behavioral factors and dementia risk, our investigation is an observational study. In such studies unrecognized confounders or bias may account for the observed results and we cannot determine cause and effect. Our study has several strengths including the advantage of population-based prospective design with all subjects found to be dementia-free at baseline based on a clinical diagnosis of dementia using standard criteria. Routine and periodic reexamination of participants at short intervals (every 6-12 months) assured the identification of early cognitive changes and dementia.

Adherence to a healthful lifestyle throughout life has proven health benefits for several chronic diseases and is associated with reduced mortality. Although a healthful lifestyle may have helped our participants to reach the age of 90, lifestyle factors measured about 20 years previously were not associated with a lower risk of dementia after age 90. Of those lifestyle factors measured at enrollment in The 90+ Study, caffeine consumption, vitamin supplement intake and social/mental activities were related to lower risk in the oldest-old. These findings of a 30 to 45% decrease in risk could represent a substantial reduction in dementia incidence and warrant further study in other very old individuals.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants R01CA32197 and R01AG21055 from the National Institutes of Health, the Earl Carroll Trust Fund, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Jorm AF, Jolley D. The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 1998;51:728–733. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Paganini-Hill A, Berlau D, Kawas CH. Dementia incidence continues to increase with age in the oldest old. The 90+ Study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:114–121. doi: 10.1002/ana.21915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson C, Feightner JW, Garcia A. General risk factors for dementia: a systematic evidence review. Alzheimers Dementia. 2007;3:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Middleton L, Yaffe K. Promising strategies for the prevention of dementia. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1210–1215. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Berlau D, Paganini-Hill A, Kawas CH. Prevalence of dementia after age 90: results from the 90+ Study. Neurology. 2008;71:337–343. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310773.65918.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paganini-Hill A, Ross RK, Henderson BE. Prevalence of chronic disease and health practices in a retirement community. J Chron Dis. 1986;39:699–707. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paganini-Hill A, Chao A, Ross RK, Henderson BE. Exercise and other factors in the prevention of hip fracture: the Leisure World Study. Epidemiol. 1991;2:16–25. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittle C, Corrada M, Dick M, Ziegler R, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Paganini-Hill A, Kawas C. Neuropsychological data in nondemented oldest old: The 90+ Study. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29:290–299. doi: 10.1080/13803390600678038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverman JM, Breitner JC, Mohs RC, Davis KL. Reliability of the family history method in genetic studies of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1279–1282. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.10.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman JM, Keefe RS, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A study of the reliability of the family history method in genetic studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1989;3:218–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawas C, Segal J, Stewart WF, et al. A validation study of the Dementia Questionnaire. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:901–906. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540210073015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark CM, Ewbank DC. Performance of the dementia severity rating scale: a caregiver questionnaire for rating severity in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1996;10:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahle-Wrobleski K, Corrada MM, Li B, Kawas CH. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mini-Mental State examination for identifying dementia in the oldest-old: the 90+ Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown J, Kreiger N, Darlington GA, Sloan M. Misclassification of exposure: coffee as a surrogate for caffeine intake. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:815–820. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.8.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H-X, Xu W, Pei J-J. Leisure activities, cognition and dementia. Biochimica et Biophysica Act. 2012;1822:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:343–353. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plassman BL, William JW, Burke JR, Holsinger T, Benjamin S. Systemic review: factors associated with risk for and possible prevention of cognitive decline in later life. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:182–193. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvalho A, Rea IM, Parimon T, Cusack BJ. Physical activity and cognitive function in individuals over 60 years of age: a systematic review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014;9:661–682. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S55520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Shah RC, Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Total daily physical activity and the risk of AD and cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2012;78:1323–1329. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson EB, Wang L, Brown JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among person 65 years of age and old. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L. Performance-based physical function and future dementia in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2006;116:1115–1120. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podewis LJ, Gullar E, Kutler LH, et al. Physical activity, APOE genotype, and dementia risk: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:639–651. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravaglia G, Forti P, Luciceasre APN, Rietti E, Bianchin M, Dalmonte E. Physical activity and dementia risk in the elderly: findings from a prospective Italian study. Neurology. 2008;70:1786–1794. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000296276.50595.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarmeas N. Physical activity, diet and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2009;302:627–637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taaffe DR, Irie F, Masaki KH, et al. Physical activity, physical function, and incident dementia in elderly men: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2008;63:529–535. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flaten V, Laurent C, Coelho JE, et al. From epidemiology to pathophysiology: what about caffeine in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:587–592. doi: 10.1042/BST20130229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carman AJ, Dacks PA, Lane RF, Shineman DW, Fillit HM. Current evidence for the use of coffee and caffeine to prevent age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18:383–392. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, Hebert R, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:445–453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eskelinen MH, Ngandu T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: a population-based CAIDE study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2009;16:85–91. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maia L, de Mendonca A. Does caffeine intake protect from Alzheimer’s disease? Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:377–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao C, Loewenstein DA, Lin X, et al. High blood caffeine levels in MCI linked to lack of progression to dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012;30:559–572. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelber RP, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Ross GW, White LR. Coffee intake in midlife and risk of dementia and its neuropathologic correlates. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011:23607–615. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Salim A, O’Kearney R. Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:367–378. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C. Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters R, Peters J, Warner J, Beckett N, Bulpitt C. Alcohol, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly: a systematic review. Age and Ageing. 2008;37:505–512. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillette Guyonnet S, Abellan Van Kan G, Andrieu S, et al. IANA task force on nutrition and cognitive decline with aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2007;11:132–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang JH, Cook N, Manson J, Buring JE, Grodstein F. A randomized trial of vitamin E supplementation and cognitive function in women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2462–2468. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paganini-Hill A, Chao A, Ross RK, Henderson BE. Vitamin A, β-carotene, and the risk of cancer: a prospective study. JNCI. 1987;79:443–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]