Abstract

Background

End of life refers to the period when people are living with advanced illness that will not stabilize and from which they will not recover and will eventually die. It is not limited to the period immediately before death. Multiple services are required to support people and their families during this time period. The model of care used to deliver these services can affect the quality of the care they receive.

Objectives

Our objective was to determine whether an optimal team-based model of care exists for service delivery at end of life. In systematically reviewing such models, we considered their core components: team membership, services offered, modes of patient contact, and setting.

Data Sources

A literature search was performed on October 14, 2013, using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews, for studies published from January 1, 2000, to October 14, 2013.

Review Methods

Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and full-text articles were obtained that met the inclusion criteria. Studies were included if they evaluated a team model of care compared with usual care in an end-of-life adult population. A team was defined as having at least 2 health care disciplines represented. Studies were limited to English publications. A meta-analysis was completed to obtain pooled effect estimates where data permitted. The GRADE quality of the evidence was evaluated.

Results

Our literature search located 10 randomized controlled trials which, among them, evaluated the following 6 team-based models of care:

hospital, direct contact

home, direct contact

home, indirect contact

comprehensive, indirect contact

comprehensive, direct contact

comprehensive, direct, and early contact

Direct contact is when team members see the patient; indirect contact is when they advise another health care practitioner (e.g., a family doctor) who sees the patient. A “comprehensive” model is one that provides continuity of service across inpatient and outpatient settings, e.g., in hospital and then at home.

All teams consisted of a nurse and physician at minimum, at least one of whom had a specialty in end-of-life health care. More than 50% of the teams offered services that included symptom management, psychosocial care, development of patient care plans, end-of-life care planning, and coordination of care. We found moderate-quality evidence that the use of a comprehensive direct contact model initiated up to 9 months before death improved informal caregiver satisfaction and the odds of having a home death, and decreased the odds of dying in a nursing home. We found moderate-quality evidence that the use of a comprehensive, direct, and early (up to 24 months before death) contact model improved patient quality of life, symptom management, and patient satisfaction. We did not find that using a comprehensive team-based model had an impact on hospital admissions or length of stay. We found low-quality evidence that the use of a home team-based model increased the odds of having a home death.

Limitations

Heterogeneity in data reporting across studies limited the ability to complete a meta-analysis on many of the outcome measures. Missing data was not managed well within the studies.

Conclusions

Moderate-quality evidence shows that a comprehensive, direct-contact, team-based model of care provides the following benefits for end-of-life patients with an estimated survival of up to 9 months: it improves caregiver satisfaction and increases the odds of dying at home while decreasing the odds of dying in a nursing home. Moderate-quality evidence also shows that improvement in patient quality of life, symptom management, and patient satisfaction occur when end-of-life care via this model is provided early (up to 24 months before death). However, using this model to deliver end-of-life care does not impact hospital admissions or hospital length of stay. Team membership includes at minimum a physician and nurse, with at least one having specialist training and/or experience in end-of-life care. Team services include symptom management, psychosocial care, development of patient care plans, end-of-life care planning, and coordination of care.

Plain Language Summary

“End of life” refers to a state where the person has an illness that is getting worse, cannot be cured or slowed down, and will eventually cause his or her death. People need many health care services to help them manage symptoms and cope with impending death, as well as to help meet their physical, emotional, and spiritual needs. How these services are delivered can affect people's comfort and quality of life, and how they will feel about their end-of-life care.

In this report we looked at different models of health care service delivery—all of them team-based—to determine the best one to use at end of life. We reviewed 10 published studies that evaluated different models. In each study, the teams had at least one nurse and one doctor, at least one of whom was experienced or trained in end-of-life care. Usually, team services included symptom management, psychosocial care, development of patient care plans, end-of-life care planning, and coordination of care.

As part of our process at Health Quality Ontario, we assess the quality of the evidence we find. This time we judged the quality to be moderate.

The evidence favoured a comprehensive team-based model with direct patient contact. “Comprehensive” means service from the same team as the patient moves through different settings, e.g., from hospital to home. “Direct contact” means that team members see the patient themselves, instead of advising another professional (such as a family doctor) who sees the patient. The evidence showed that using this care-delivery model for people who were expected to live up to 9 more months improved caregiver satisfaction and increased the chance of dying at home. However, offering end-of-life services earlier, when a person had up to 24 more months to live, improved symptom management, patient satisfaction, and patient's quality of life.

Background

In July 2013, the Evidence Development and Standards (EDS) branch of Health Quality Ontario (HQO) began work on developing an evidentiary framework for end of life care. The focus was on adults with advanced disease who are not expected to recover from their condition. This project emerged from a request by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care that HQO provide them with an evidentiary platform on strategies to optimize the care for patients with advanced disease, their caregivers (including family members), and providers.

After an initial review of research on end-of-life care, consultation with experts, and presentation to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC), the evidentiary framework was produced to focus on quality of care in both the inpatient and the outpatient (community) settings to reflect the reality that the best end-of-life care setting will differ with the circumstances and preferences of each client. HQO identified the following topics for analysis: determinants of place of death, patient care planning discussions, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, patient, informal caregiver and healthcare provider education, and team-based models of care. Evidence-based analyses were prepared for each of these topics.

HQO partnered with the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the selected interventions in Ontario populations. The economic models used administrative data to identify an end-of-life population and estimate costs and savings for interventions with significant estimates of effect. For more information on the economic analysis, please contact Murray Krahn at murray.krahn@theta.utoronto.ca.

The End-of-Life mega-analysis series is made up of the following reports, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ohtas-reports-and-ohtac-recommendations.

-

▸

End-of-Life Health Care in Ontario: OHTAC Recommendation

-

▸

Health Care for People Approaching the End of Life: An Evidentiary Framework

-

▸

Effect of Supportive Interventions on Informal Caregivers of People at the End of Life: A Rapid Review

-

▸

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Patients with Terminal Illness: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

The Determinants of Place of Death: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

Educational Intervention in End-of-Life Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

End-of-Life Care Interventions: An Economic Analysis

-

▸

Patient Care Planning Discussions for Patients at the End of Life: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

Team-Based Models for End-of-Life Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Objective of Analysis

The objective was to systematically review team-based models of care for end-of-life service delivery, to determine whether an optimal model exists. Our review considered the core model components of team membership, services offered, mode of patient contact, and setting.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Description of Disease/Condition

End of Life is defined as “a phase of life when a person is living with an illness that will worsen and eventually cause death.” (1) It is important to note that this is not limited to the period immediately before death. Some have described a palliative phase (a phase when the person is managing the illness and its symptoms but no cure is expected) and an end-of-life phase (the time point immediately before death). (2) In this report we use “end of life” to encompass both. To provide end-of-life care that is effective and of high quality, a variety of critical areas need to be considered. Symptom management and prevention, support for families and caregivers, providing continuity of care, respect for people and for their informed decision making, support for spiritual and psychosocial well-being, and support for overall physical function—these are but some of the essential elements common to end-of-life care. (1) The optimal time to initiate end-of-life care has not been determined.

Ontario Context

Based on data from IntelliHealth Ontario, about 87,000 people die in Ontario annually. In October 2005, the province's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care announced a 3-year, $115.5-million end-of-life care strategy aimed to integrate and enhance end-of-life home care services. (3) It had 2 main objectives: first, to shift end-of-life care from acute settings to alternative settings of people's choice, such as their homes; and, second, to improve the coordination and consistency of the services provided. Preliminary evaluation of this strategy indicated that the number of people receiving end-of-life care increased after its implementation. Home nursing visits increased by 26%, nursing hours by 31%, and personal support worker hours by 47% in the province. However, a study by Seow et al, (4) reported that 1 year after the implementation of the strategy patients’ use of end-of-life home care and acute services remained unchanged. Furthermore, the proportion of in-hospital deaths remained stable at 38%. The authors indicated that further evaluation was needed to determine the effects of the strategy on the health care system.

The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is working with the Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs) and delivery partners, families, and researchers to continue to advance care delivery at this phase of life through a shared declaration, the Declaration of Partnership and Commitment to Action. (2) It “represents a common vision for palliative care in Ontario that is integrated with chronic disease management and outlines the key priorities and actions that all partners are committing to take in order to achieve the vision.” The declaration proposes a new model of care for end-of-life services—one that comprises integrated interprofessional teams, and coordinates and continually updates a care plan encompassing all settings where the patient receives care.

Technology/Technique

One article defines model of care as an “overarching design for the provision of a particular type of health care service.” (5) Authors Davidson et al say, “It consists of defined core elements and principles and has a framework that provides the structure for the implementation and subsequent evaluation of care.” Additionally they state that “having a clearly defined and articulated model of care will help to ensure that all health professionals are all actually viewing the same picture, working toward a common set of goals and, most importantly, are able to evaluate performance on an agreed basis.”

It is imperative—for empirical evaluation, and also for implementation—to distinguish the framework of a model from the core elements that define the model. Using Davidson et al's (5) conceptual definition of a model of care, the studies included in recent systematic reviews share a common framework: team-based design. However, these team-based models differ in terms of their core elements, which, according to Davidson et al, help to define a model. Zimmermann et al (6) and Luckett et al (7) looked at the effectiveness of specialized end-of-life care teams in a variety of health care settings. Here the core element evaluated was team membership, comparing specialist team models with non-specialist team models. Both Shepperd et al (8) and Gomes et al (9) evaluated a team-based model of care in the patient's home, while Hall et al (10) evaluated the same model in a nursing home setting. Besides model membership and setting, other core elements have been evaluated in the literature, including services offered and mode of patient contact. Given this, the core elements of team-based models of care considered in this review include team membership, team services, mode of patient contact, and setting.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Questions

Is there an optimal team-based model of care for delivery of end-of-life services? What is the effectiveness of different team-based models on relevant patient, caregiver, health care provider, and system-level outcomes?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on October 4, 2013, using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews, for studies published from January 1, 2000, to October 14, 2013. (Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategies.) Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search. E-alerts were set up to update the literature search on an ongoing basis between October 4, 2013 and Sept 2, 2014.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

published between January 1, 2000 and October 14, 2013

systematic reviews (SRs) with meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

adults (aged 18 years and over) with advanced disease which is not expected to stabilize and from which they are not expected to recover

study populations comprising at least 90% adults

team-based models of care which include at least 2 different professional services

Exclusion Criteria

non-randomized controlled trials, observational studies, case reports, editorials, letters, comments, conference abstracts

children (under 18 years of age)

studies with adult and child populations where summary data for the adult target population cannot be discretely extracted

Outcomes of Interest

patient quality of life

patient symptom management

patient satisfaction

informal caregiver satisfaction

health care provider satisfaction

number of emergency department visits

number of hospital admissions

number of admissions to the intensive care unit

hospital length of stay

place of death

Statistical Analysis

We completed a meta-analysis, where appropriate and possible, using a random effects model. We did an a priori subgrouping by type of team-based model of care, and determined statistical heterogeneity by inspecting Forest plots for non-overlapping confidence intervals and disparate effect sizes across studies, as well as using the I2 statistic. Heterogeneity of 0% to 40% measured by the I2 statistic may not be important; 30% to 60% is moderate, 50% to 90% is substantial, and 75% to 100% is considerable. Where meta-analysis could not be completed, we have provided a narrative description of the studies’ results.

Quality of Evidence

The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) measurement tool is used to assess the quality of systematic reviews. (11)

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. (12) The overall quality was determined to be high, moderate, low, or very low using a step-wise, structural methodology.

Study design was the first consideration; the starting assumption was that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are high quality, whereas observational studies are low quality. Five additional factors—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—were then taken into account. Any limitations in these areas resulted in downgrading the quality of evidence. Finally, 3 main factors that may raise the quality of evidence were considered: large magnitude of effect, dose response gradient, and accounting for all residual confounding factors. (12) For more detailed information, please refer to the latest series of GRADE articles. (12)

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the final quality score can be interpreted using the following definitions:

| High | High confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderate confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but may be substantially different |

| Low | Low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very Low | Very low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

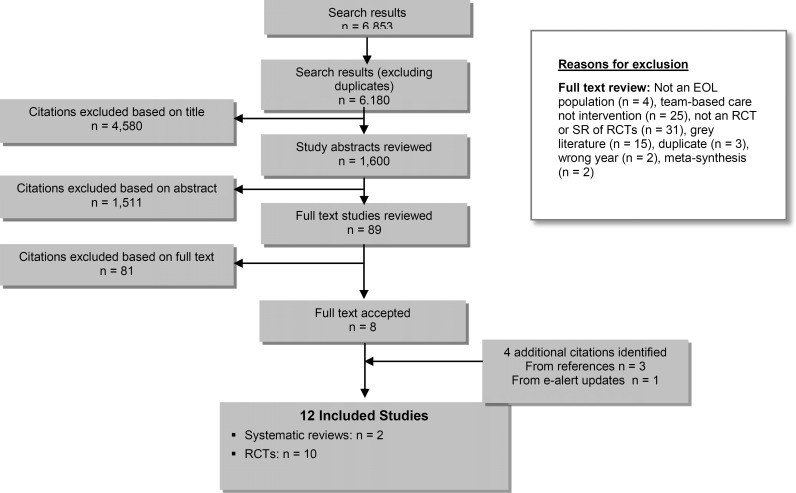

A literature search was performed on October 4, 2013. The database search initially yielded 6,853 citations, after which 673 duplicates were removed for a final yield of 6,180. Articles were then excluded based on information in the title and abstract. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment. Eight studies—2 systematic reviews and 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the included studies and health technology assessment websites were hand-searched to identify other relevant studies, and 2 additional RCTs were included. One additional RCT was identified through the e-alert system updates of the literature search. The reference list of this study was reviewed and 1 additional RCT was identified, for a total of 12 studies (2 systematic reviews and 10 RCTs). Figure 1 provides a breakdown of when and why citations were excluded.

Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart.

For each included study, the study design was identified and is summarized below in Table 1, a modified version of a hierarchy of study design by Goodman. (13)

Table 1:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| RCTs | ||

| Systematic review of RCTs | 2 | |

| Large RCT (n≥100) | 8 | |

| Small RCT | 2 | |

| Observational Studies | ||

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with contemporaneous controls | ||

| Non-RCT with non-contemporaneous controls | ||

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with historical controls | ||

| Non-RCT with historical controls | ||

| Database, registry, or cross-sectional study | ||

| Case series | ||

| Retrospective review, modelling | ||

| Studies presented at an international conference Expert opinion | ||

| Total | 12 | |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Systematic Reviews

Table 2 describes the systematic reviews included in this analysis. Gomes et al (9) evaluated team-based end-of-life care for patients at home, while Higginson et al (14) evaluated team-based end-of-life care irrespective of setting. The literature search by Higginson et al included citations up to 2000, while that by Gomes et al continued until 2012. Both had high AMSTAR ratings (see Appendix 2, Table A1).

Table 2:

Characteristics of Systematic Reviews on Team-Based End-of-Life Care

| Author, Year | Study Designs Included | Search Dates | Population | Intervention | Control | AMSTAR Scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gomes et al, 2013 (9) | 5 RCT 2 non-RCT | Up to 2012 | Patients with cancer, COPD, CHF, HIV/AIDS, MS | Team delivering home end-of-life care to people with a severe or advanced disease no longer responding to curative/maintenance treatment or symptomatic or both. | Usual care | 11 |

| Higginson et al, 2003 (14) | 16 RCT 3 non-RCT | Up to 2000 | Progressive life-threatening illness | Specialist end-of-life care team. | Usual care | 8 |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; AMSTAR, Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency syndrome; MS, multiple sclerosis; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Highest score possible is 11.

Both systematic reviews pooled data from the randomized and non-randomized controlled trials (RCTs and nRCTs) that they included. Gomes et al (9) reported a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of home death for people receiving team-based end-of-life care at home, compared with those receiving usual care. This was true both when the RCT data were pooled alone and pooled with the nRCT data. The likelihood of nursing-home death decreased to a statistically significant degree when the RCT and nRCT data were pooled, but the decrease did not reach statistical significance when the RCT data were pooled alone. The likelihood of dying in a hospital or in an inpatient hospice/end-of-life care unit did not differ among treatment groups, whether RCT data were pooled alone or with nRCT data. In contrast, Higginson et al (14) reported no difference in the rate of home death for people receiving team-based end-of-life care compared with usual care. They did report a decrease in pain and symptoms among the team-care patients—statistically significant when RCT data were pooled with nRCT data but not when they were pooled alone. Table 3 shows the results of the meta-analyses from both reviews.

Table 3:

Results of Systematic Reviews on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Meta-analyses

| Author, Year | Outcome | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Gomes et al, 2013 (9) | Home death | 2.21 (1.31–2.71) 5 RCTs, 2 nRCTs 1.73 (1.28–2.33) 5 RCTs |

| Nursing home death | 0.31 (0.12–0.79) 4 RCTs, 2 nRCTs 0.29 (0.08–1.13) 4 RCTs, |

|

| Hospital death | 0.64 (0.40–1.03) 4 RCTs, 1 nRCTs 0.63 (0.38–1.02) 4 RCTs |

|

| Inpatient hospice/EoL care unit death | 1.46 (0.51–4.19) 4 RCTs, 1 nRCT 1.96 (0.36–10.98) 4 RCTs |

|

| Higginson et al, 2003 (14) | Home death | 0.63 (0.25–1.57) 3 RCTs, 5 nRCTs 0.92 (0.52–1.63) 3 RCTs |

| Pain | 0.38 (0.23, 0.64) 3 RCTs, 7 nRCTs 0.82 (0.52–1.28) 3 RCTs |

|

| Symptoms | 0.51 (0.30–0.88) 2 RCTs, 6 nRCTs 0.55 (0.21–1.38) 3 RCTs |

|

| Satisfaction | 0.41 (0.12–1.47) 1 RCT, 1 nRCT 0.65 (0.36–1.18) 1 RCT |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EoL, end of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Of the 10 RCTs identified in our literature search (15–24) 1 study, conducted by Jordhoy et al, is discussed in 3 different articles. (21, 25, 26) Multiple chronic conditions are featured in the study populations of the RCTs, with cancer being prevalent. People with dementia were enrolled in the studies by Ahronheim et al and Gade et al. (15, 19) Four studies (15, 18–20) evaluated a hospital team-based model of care. Two studies evaluated a home team-based model of care, 1 with direct contact (17) and 1 with indirect contact. (16) We defined direct contact as when the team members see the patient themselves, and indirect contact as when they advise another health care provider (e.g., a family doctor) who sees the patient. Four studies evaluated a comprehensive team-based model of care, 3 with direct contact (21, 23, 24) and 1 with indirect contact. (22) We defined a comprehensive model of care as one where the same team follows the person across inpatient and outpatient care settings. In 2 of the studies evaluating a comprehensive model, patients were contacted early in the trajectory of their disease. Zimmermann et al (24) enrolled those with an estimated survival of 6 to 24 months and Temel et al (23) enrolled people within 8 weeks of their diagnosis with metastatic lung cancer. People enrolled in the study by Temel et al (23) had a longer mean survival time than those in the other 5 studies that reported survival time: Gade et al (19), Hanks et al (20), Brumley et al (17), Mitchell et al (22), and Jordhoy et al. (25) Zimmermann et al (24) did not collect data on the mean survival time as this was not considered a relevant outcome (personal communication with author, March 5, 2014). However, Zimmermann et al did report estimated survival-time inclusion criterion of up to 24 months, which is twice that of those studies for which we have similar data, including Gade et al (19), Brumley et al (17), Mitchell et al, (22) and Jordhoy et al. (21) This may suggest that people enrolled in the Zimmermann et al (24) study were enrolled earlier in the end-of-life trajectory.

Defining Models of Care

In this analysis, we consider the 4 core elements of team-based care delivery—team membership, services provided, setting, and mode of patient contact. Using the latter 2 elements as a basis for our definitions, and also taking the time of patient contact into account, we identified 6 models of team-based end-of-life health care to evaluate. The models are:

hospital setting, direct contact

home setting, direct contact

home setting, indirect contact

comprehensive setting, indirect contact

comprehensive setting, direct contact

comprehensive setting, direct and early contact

Table 4 describes the 10 RCTs located by our literature search and identifies them by model.

Table 4:

RCTs Examining Team-Based End-of-Life Care

| Author, Year | Country | Sample Size | Population | Mean Age, years | Estimated Survival Time, months | Mean Survival Time, days EoL Team/Usual Care | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Australia | 20 | Multiple conditions | 76 | NR | NR | Hospital, Direct Contact |

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | US | 517 | Cancer, CHF, MI, COPD, ESRD, organ failure, stroke, dementia (4%) | 73 | ≤12 | 30a/36 | Hospital, Direct Contact |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | UK | 261 | Cancer | 68 | NR | 76/76 | Hospital, Direct Contact |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | US | 99 | Advanced dementia | 85 | NR | NR | Hospital/Direct Contact |

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | US | 310 | Cancer, CHF, COPD | 74 | ≤12 | 196/242 | Home, Direct Contact |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | US | 190 | COPD, CHF | 69 | NR | NR | Home, Indirect Contact |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | Australia | 159 | Conditions not specified | 68a | >1 | 55/73 | Comprehensive, Indirect Contact |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21, 25, 26) | Norway | 434 | Cancer | 70a | 2-9 | 99a/127 | Comprehensive, Direct Contact |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | Canada | 461 | Cancer | 61 | 6-24 | NR | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | US | 151 | Cancer | 64 | Enrolled within 8 weeks of diagnosis of metastatic lung cancer | 348/267 | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start |

Abbreviations: CHF; congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EoL, end of life; ESRD, end stage renal disease; MI, myocardial infarction; NR, not reported; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Median.

Treatment Group

Tables 5 through 9 detail the core components of the team model used in the treatment group, including team membership (Tables 5 and 6), team services (Tables 7 and 8), and team mode of patient contact and setting of care (Table 9). Team care was interdisciplinary and provided coordination of services. A minimum core membership among all studies included a physician and nurse, at least one of whom was specialized in end-of-life health care. Team services as described in the studies are reported in Table 7. More than 50% of studies included symptom management, psychosocial care, end-of-life care planning, development of care plans, and continuity of care methods as their core services offered. Patient and family education, spiritual care, and medication consultation were included as services in 40% or less of the studies. Continuity of care was present if the team created links with other services and/or the person's family physician, to reduce fragmentation of services. Table 9 reports mode of contact and setting of care. A comprehensive setting of care included care that was provided across inpatient and outpatient (including clinic and home) settings. Four studies provided care in a comprehensive care setting, 2 in the home setting, and 4 in the hospital setting.

Table 5:

End-of-Life Care Teams—Core Membership, Among Included RCTs

| Author, Year | Core Membership |

|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Physician, registrar, resident, clinical nurse consultant. |

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | EoL care physician, nurse, social worker, chaplain. |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Academic consultants, specialist registrar, clinical nurse specialist. Core team had links to clinical psychologist, social workers, rehabilitation staff, and chaplain. |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | Clinical nurse specialist, physician experienced in assessment of people with advanced dementia, geriatrician. |

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | Physician, nurse, social worker. |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Nurse case managers, medical director, social worker, pastoral counsellor, primary care physician, health plan case manager (if one exists). |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | EoL care physician and EoL care nurse. |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | EoL care nurses, social worker, priest, nutritionist, physiotherapist, physician. |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | EoL care physician and nurse. |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | EoL care physician and advanced practice nurse. |

Abbreviation: EoL, end of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 9:

End-of-Life Care Team Mode of Contact and Practice Setting, Among Included RCTs

| Author, Year | Method of Contact | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Direct | Hospital |

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Direct | Hospital |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Direct | Hospital |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | Direct | Hospital |

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | Direct | Home |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Indirect via nurse case managers | Home |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | Indirect via case conferencing with GP | Comprehensive |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | Direct | Comprehensive |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | Direct, Early Start | Comprehensive |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | Direct, Early Start | Comprehensive |

Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 6:

End-of-Life Care Team Membership at a Glance—Core and Extended, Among Included RCTs

| Author, Year | MD | RN | Social Worker | Spiritual Advisor | Nutritionist | Geriatrician | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | ✓ | ✓ | Registrar, resident | ||||

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | ✓ | ✓ | Academic consultants; links to psychologist, social worker, rehab staff, hospital chaplain | ||||

| Abronheim et al, 2000 (15) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Chaplain, bereavement coordinator, home health aide, pharmacist dietician, PT, OT, SP, all as needed | |||

| Aiken et al, 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Health plan case manager, if existing | ||

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Jordhoy al, 2000 (21) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Part-time PT | |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Total number of Studies | 10 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | N/A |

Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; MD, medical doctor; N/A, not applicable; OT, occupational therapist; PT, physiotherapist; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RN, registered nurse; SP, speech pathologist.

Table 7:

End-of-Life Care Teams—Services Provided, Among Included RCTs

| Author, Year | Team Services |

|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Daily ward rounds. EoL team care in addition to ICU care. |

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Symptom management assessment, psychological and spiritual support, end-of-life planning, post-hospital admission care, development of care plan. |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Initial assessment by MD or RN, with any problems identified written in case notes and communicated to medical and nursing team in person or by phone. Weekly re-assessment of person. |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | Symptom management, rehabilitation measures, massage therapy, counselling surrogate decision makers about patient rights, alternate care planning. Development of EoL care plan at discharge. |

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | Symptom management, medical care, goals-of-care discussions, education. Assessment of social, spiritual, psychological, and medical needs. Development of care plan. |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Symptom management, education services, advance care planning, medical compliance assessment. Addressing of psychological and spiritual needs. Development of advance care plans and emergency response plan. |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | Development of care plan. |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | Development of care plan. |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | Symptom assessment, help with psychological distress, social support, home services, monthly clinic follow up, 24-hour on-call telephone service, coordination of home nursing care and home EoL care, physician transfer if needed, admission to EoL care unit. |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | Assessment of physical and psychosocial symptoms, establishment of goals of care, assistance with decision making regarding treatment, coordination of care based on individual needs. |

Abbreviations: EoL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit; MD, medical doctor; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RN, registered nurse.

Table 8:

End-of-Life Care Team Services at a Glance, Among Included RCTs

| Medication | Symptom Management | Psychosocial | Spiritual | End-of-Life Planning | Patient/Family Education | Care Plan | Continuity of Care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | ||||||||

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | ||||||||

| Abronheim et al, 2000 (15) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Zimmerman et al, 2014 (24) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Total number of studies | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Control Group

The control group, i.e., usual-care group, received multidisciplinary care mostly on an ad hoc basis. The major difference between the treatment and control group in the studies was that team care for the former was coordinated, while team care for the latter was not. Table 10 describes the usual care control groups in the 10 included RCTs.

Table 10:

RCTs on Team-Based EoL Care—Care Received by Control Groups

| Author, Year | Usual Care | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | ICU care | Usual ICU care without EoL care consultation. |

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital care | Usual care in one of 3 hospitals that were part of an MCO delivery system. All hospitals had an MCO hospitalist physician and 1 study site had a primary care internist. All hospital sites had social workers and chaplains on staff, who provided direct patient services to usual-care patients. |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Telephone EoL care team advisory to staff | The control group was the telephone EoL care team group. No direct contact between the EoL care team and the patient or family. A telephone consultation took place between a senior medical member of the EoL care team and the referring doctor and also between an EoL care team nurse specialist and a member of the ward nursing staff directly involved with the patient. A second telephone consultation could be made, if needed, but no follow up or consultation thereafter. |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | Primary care team only | Usual hospital care by primary care team without the input of the EoL care team. |

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | Medicare guidelines for home health care | Standard care that followed guidelines for home health care. Various levels of home health care, acute care and primary care services, and hospice care. Treatment for conditions and symptoms, and ongoing home care if needed. |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Care by an MCO | Usual care provided by the MCO included case management, disease and symptom education, nutrition, psychological counselling, transportation, coordination of medical service. Services delivered by phone and occasional home visits. |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | Case review by EoL care team with report to general practitioner | Case review by the specialist team with routine communication with the general practitioner thereafter (faxed or posted letter), and telephone communication between general practitioner or domiciliary nurses, present at the specialist team meeting, acting in intermediary role. |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | Usual care | No EoL care team. Approximately 15 social workers, 3 priests, 47 physiotherapists serving 946 beds. |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | No formal consultation but EoL care referral was not denied | Oncologist and oncology nurses. Ad hoc visits based on chemotherapy or radiation schedule, access to 24-hour on-call service of resident, telephone follow up as needed. No structured symptom assessment, no routine psychosocial assessment. EoL care referral if requested. Those who received EoL care referral received same care as intervention group but without monthly follow up. |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | Routine oncologic care, EoL care referral if requested | Routine oncologic care. Met with EoL care service only upon request by patient, family, or oncologist. |

Abbreviations: EoL, end of life; GP, general practitioner; ICU, intensive care unit; MCO, management care organization; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Outcomes

Patient Quality of Life

Six studies reported on patient quality of life (QOL) as an outcome, all using comparison of change scores for each group. Other than Hanks et al (20) and Jordhoy et al (21), the studies used different QOL measures. Because of this, the data were not amenable to meta-analysis; we tried to contact authors to obtain homogeneity in data, but were not successful. Based on inspection of the P values, a statistically significant improvement was seen in patient QOL when using a comprehensive team-based model and starting early in the end-of-life trajectory, compared with usual care. The quality of this evidence is moderate (see Appendix 2). The study by Jordhoy et al (21) reported a nonsignificant effect on QOL with a comprehensive team-based model, compared with usual care, measured at 16 weeks after study enrolment in people with an estimated survival of less than 1 year. This evidence, too, is of moderate quality (see Appendix 2). A difference can be seen, then, between the Jordhoy et al (21) findings—on team-based comprehensive care—and the Temel et al (23) and Zimmermann et al (24) findings—on team-based comprehensive care with an early start. This may support the view that starting end-of-life team care earlier improves a person's QOL. However, the difference in effect between studies may be due, as well or instead, to their use of different QOL measures. Table 11 shows the quality-of-life results.

Table 11:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Patient Quality of Life Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Self-reported QOL | 2 | 0.78 |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Hospital, Direct Contact | EORTC QLQ-C30 | 1 | 0.45 |

| Mitchell et al, 2008 (22) | Comprehensive, Indirect Contact | AQEL | 2 | 0.37 |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact | EORTC QLQ-C30 | 16 | > 0.1 |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start | FACIT-Sp QUAL-E FACIT-Sp QUAL-E |

12 12 16 16 |

0.07 0.05 0.006 0.003 |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start | TOI | 12 | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: AQEL, Assessment of Quality of Life at the End of Life questionnaire; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL-C30 questionnaire; FACIT-Sp, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale; QOL, quality of life; QUAL-E, Quality of Life at the End of Life instrument; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TOI, trial outcome index.

Symptom Management

Four studies reported results for the outcome of patient symptom management. Three of them used comparison of change scores for each group, and 1, Aiken et al (16), compared group scores at a specific time point. Each study used a different symptom-management measure to assess outcomes, so the data were not amenable to meta-analysis. We tried to contact authors to obtain homogeneity in data, but were not successful. Table 12 reports the results for symptom management.

Table 12:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Symptom Management Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Physical area scale | 2 | 0.91 |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Hospital, Direct Contact | VAS—severity of most bothersome symptom | 1 | 0.48 |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Home, Indirect Contact | Likert scale—frequency, severity, distress of most bothersome symptom | Baseline 12 24 |

COPD group < 0.05 less distress at 12 weeks in team care vs. control CHF group < 0.05 more distress at 24 weeks in team care vs. control |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start | ESAS | 12 16 |

0.33 0.05 |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESAS; Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; vs., versus.

Patient Satisfaction

Four studies reported results for the outcome of patient satisfaction. Each used a different assessment measure, so the data were not amenable to meta-analysis. Our attempts to contact authors to obtain homogeneity in data were not successful. Based on inspection of the P values, there is a statistically significant improvement in patient satisfaction with a comprehensive team-based model of care started early, compared with usual care. The quality of this evidence is moderate (see Appendix 2). There is also a statistically significant improvement in patient satisfaction at 30 and 90 days post-enrolment, in people receiving team-based care at home, compared with usual care. Patients in a hospital treated by a team with direct contact also showed a statistically significant improvement in satisfaction 1 week post study enrolment. The quality of this evidence is low (see Appendix 2). Table 13 shows patient satisfaction results.

Table 13:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Patient Satisfaction Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital, Direct Contact | MCOHPQ | 1 | 0.001 |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Hospital, Direct Contact | MacAdam's Assessment of Suffering Questionnairea | 1 | Nonsignificant (exact value not reported) |

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | Home, Direct Contact | Reid-Gundlach Satisfaction with Services instrument | Baseline 30 days 60 days 90 days |

0.006 0.26 0.03 |

| Zimmermann et al, 2014 (24) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start | FAMCARE-P16 scale | 12 16 |

0.000 < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: MCOHPQ, Modified City of Hope Patient Questionnaire; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Questionnaire assessed 4 areas: i) information given about illness; ii) information given about treatment and medication; iii) availability of doctors for discussion; iv) availability of nurses for discussion.

Informal Caregiver Satisfaction

Two studies reported results for the outcome of caregiver satisfaction. Cheung et al (18) looked at differences between treatment and control groups in change scores (i.e., differences in the changes in each group's scores) from randomization to the patient's death or their discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU). Jordhoy et al (21) evaluated the difference in the mean at 4 weeks after the patient's death. The 2 studies used different satisfaction measures, so the data were not amenable to meta-analysis. Our attempts to contact authors to obtain homogeneity in data were not successful. Inspection of the P values showed a statistically significant improvement in informal-caregiver satisfaction at 4 weeks after the patient's death if a comprehensive team-based model of care has been used, compared with usual care. The quality of this evidence is moderate (see Appendix 2). Table 14 shows the results of the 2 studies.

Table 14:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Informal-Caregiver Satisfaction Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Hospital, Direct Contact | New questionnaire developed by author | Mean difference between groups of change scores from randomization to the patient's death or their discharge from ICU. | 0.56 |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact | FAMCARE | 4 weeks after patient's death. | 0.008 |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Health Care Provider Satisfaction

One study (18) reported results for the outcome of health care provider satisfaction when working in a team-based model of care, compared with a usual care model. Cheung et al (18) evaluated the difference between treatment and control groups in the changes in nurses’ and intensivists’ satisfaction scores from randomization to patient death or patient discharge from ICU. The questionnaire they used was new and was developed by the authors; its reliability and validity were not reported in the publication. A change was seen in nurses’ satisfaction levels between the 2 groups at 4 weeks after patient death, but it was not statistically significant. The authors reported a statistically significant change in intensivist satisfaction, in favour of the team-based model, when they tested the comparison using an ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) statistical test. But when they used the Mann-Whitney test, which is non-parametric, this comparison did not reach significance. They did not give their rationale for using the different tests or say which one represented the best statistical comparison. For this reason, results of the intensivists’ satisfaction are inconclusive, and we did not assess the GRADE quality of this evidence (Appendix 2). Table 15 shows the results.

Table 15:

RCT on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Health Care Provider Satisfaction Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Hospital, Direct Contact | New questionnaire developed by study authors | Patient death or patient discharge from ICU | 0.23 Nurses 0.008 Intensivistsa 0.42 Intensivistsb |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Analyzed with an ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) statistical test.

Analyzed with a Mann-Whitney statistical test.

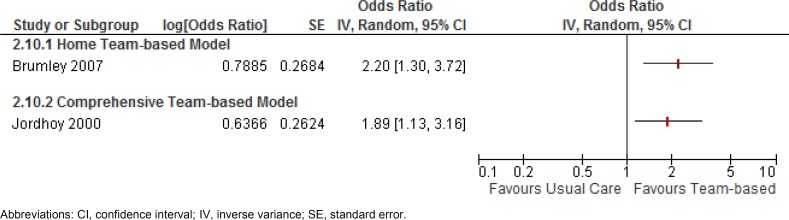

Home Death

Two studies (17, 21) reported results for the outcome of home death. A home or comprehensive team-based model of care was shown to increase the odds of dying at home by 89% or more. The GRADE quality of this evidence is low for the home team-based model and moderate for the comprehensive team-based model. (See Appendix 2.) Figure 2 gives the results.

Figure 2: Results of RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Odds Ratios for Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

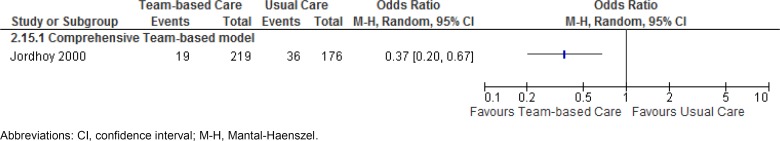

Nursing Home Death

A single study (21) reported results for the outcome of nursing home death. A comprehensive team-based model of care was shown to reduce the odds of a nursing home death by 63%. The GRADE quality of this evidence is moderate (see Appendix 2). Figure 3 gives the results.

Figure 3: Results of RCT on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Odds Ratio for Nursing Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantal-Haenszel.

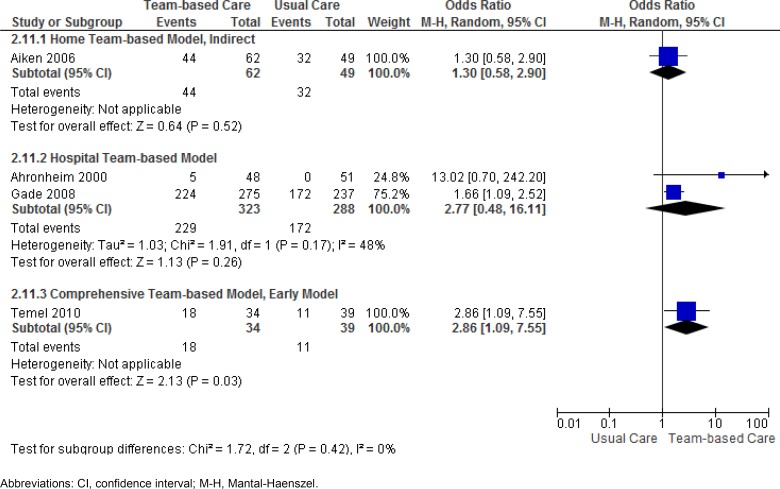

Advance Care Planning

Four studies (15, 16, 19, 23) reported results for the outcome of advance care planning. The comprehensive team-based model of care was shown to almost triple the odds of completing advance care planning, compared with usual care. The GRADE quality for this evidence, however, is low. (See Appendix 2.) Results for the hospital team-based model were not statistically significant when pooled. However, the pooled estimate for this model was greatly affected by the lack of precision in the effect estimate of the Ahronheim et al study. (15) (See Appendix 2.) With this study removed, a hospital team-based model is shown to increase the odds of completing advance care planning by at least 1.6 times that of usual care, and the quality of the evidence can be considered moderate. A nonsignificant effect was seen with a home team-based model which used an indirect mode of patient contact. Results for the outcome of advance care planning are shown in Table 16 and Figure 4.

Table 16:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Advance Care Planning Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Proportion of people with advance directives completed | 2.4 | 0.001 |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Proportion of people with a living will | 1.3 | Not significant |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Home, Indirect Contact | Proportion of people with advance directives for medical treatment or with living will | Baseline 12 24 |

Not significant 0.05a Not significant |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start | Proportion of people with resuscitation preferences documented in the outpatient electronic medical record | 24 | 0.05 |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Adjusted proportions; author does not provide details of adjustment.

Figure 4: Results of RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Odds Ratios for Advance Care Planning.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantal-Haenszel.

Note: Data used for Figure 4 obtained from proportions reported in study for participants remaining at 12 weeks post-enrolment, having living will or advance directive for medical treatment. Discrepancy between reported statistical significance in publication and nonsignificance in Figure 4 may be due to adjusted proportions.

Emergency Department Visits

Three studies (16, 17, 23) reported results for the outcome of emergency department visits. A statistically significant reduction was seen in emergency department visits with a home team-based model of care, compared with usual care. The quality of this evidence is low (see Appendix 2). Table 17 shows the results.

Table 17:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Emergency Department Visit Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brumley et al, 2007 (17) | Home, Direct Contact | Proportion of people visiting ED | 16 | 0.01 |

| Aiken et al, 2006 (16) | Home, Indirect Contact | Average ED visits per month | 24 | Not significant |

| Temel et al, 2010 (23) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact, Early Start | Proportion of people visiting ED from time of enrolment to death | 24 | 0.69 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

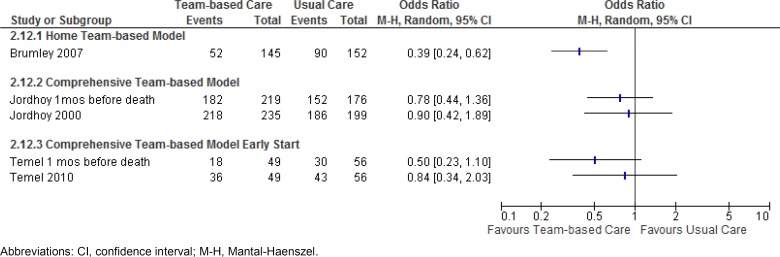

Hospital Admission

Three studies reported results for the outcome of hospital admission (number of people admitted to hospital). In Figure 5, the results presented for Jordhoy et al (21) and Temel et al (23) are for admissions in the last month before death and for the total number of admissions for the duration of the study. A home team-based model of care was shown to decrease the odds of a hospital admission by 61%. The quality of this evidence is considered low (see Appendix 2). Hospital admissions were not found to differ significantly between usual care and a comprehensive team-based model, or between usual care and a comprehensive team-based model started early. The quality of the evidence is moderate for the former and very low for the latter.

Figure 5: Results of RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Odds Ratios for Hospital Admission.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantal-Haenszel.

Intensive Care Admission

A single study reported results for the outcome of ICU admission. Gade et al (19) indicated a statistically significant decrease in ICU admissions with a hospital team-based model of care, compared with usual care. They determined this result from 2 of their 3 participating study sites, because data were missing from participants at the third site (45 people in the team-based care group and 19 people in the usual care group). This missing data, which was not statistically managed in the study, lowers the quality of this evidence, which is therefore considered low (see Appendix 2). Table 18 shows the results.

Table 18:

RCT on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Intensive Care Admission Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post-enrolment (weeks) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Number of admissionsa | 24 | 0.04 |

Abbreviation: RTC, randomized controlled trial.

The admissions data come from only 2 of the study's 3 participating sites. Total number of participants from the 3 sites: team care, 275; usual care, 237. Total number from the 2 sites reported on: team care, 230; usual care, 218.

Hospital Length of Stay

Five studies reported results for the outcome of length of stay. A difference was found in length of stay between a hospital team-based model of care and usual care, but it was not statistically significant. The quality of this evidence is moderate. Similarly, a nonsignificant difference was found between a comprehensive team-based model of care and usual care. The quality of this evidence is also moderate. The results are shown in Table 19.

Table 19:

RCTs on Team-Based End-of-Life Care—Hospital Length-of-Stay Results

| Author, Year | Model of Care | Measure | Assessment Time Point, post enrolment | Team-Based Care (Days) | Usual Care (Days) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al, 2010 (18) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Median (IQR) | Discharge/Death | 5 (8) | 11 (27) | 0.44 |

| Gade et al, 2008 (19) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Median (IQR) | Discharge/Death | 7 (4, 12) | 7 (4, 12) | 0.57 |

| Hanks et al, 2002 (20) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Mean (SD) | Discharge/Death | 14.7 (9.4) | 13.2(9.6) | NR |

| Ahronheim et al, 2000 (15) | Hospital, Direct Contact | Mean (SD) | Discharge/Death | 8.8 (NR) | 9.7 (9.6) | 0.46 |

| Jordhoy et al, 2000 (21) | Comprehensive, Direct Contact | Mean (SD) | Discharge/Death | 10.5 (7.3) | 11.5 (8.9) | NR |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NR, not reported; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; UC, usual care.

Summary

Table 20 gives a summary of the evidence for each outcome, for each of the 6 models of care. The GRADE quality of evidence is reported where possible. We did not do a GRADE assessment where results were inconclusive or study data were not available.

Table 20:

Systematic Review of Team-Based Models of End-of-Life Care—Summary of Evidence

| Outcome | Team-Based Model of Carea | Number of Studies | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Quality of Life | Hospital | 2 | Nonsignificantb | Low |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 1 | Nonsignificantb | Low | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | Nonsignificantb | Moderate | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 2 | Significant | Moderate | |

| Symptom Management | Hospital | 2 | Nonsignificantb | Low |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 1 | Inconclusiveb | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 1 | Significantb | Moderate | |

| Patient Satisfaction | Hospital | 2 | Inconclusiveb | NA |

| Home | 1 | Significantb | Low | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 1 | Significant | Moderate | |

| Caregiver Satisfaction | Hospital | 1 | Nonsignificantb | Low |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | Significantb | Moderate | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Health Care Provider Satisfaction | Hospital | 1 | Inconclusiveb | NA |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home Death | Hospital | 0 | No data | NA |

| Home | 1 | 2.2 (1.30–3.72) | Low | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | 1.89 (1.13–3.16) | Moderate | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Nursing Home Death | ||||

| Hospital | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | 0.37 (0.20–0.67) | Moderate | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Advance Care | Hospital | 2 | 2.77 (0.48–16.11) | Very Low |

| Planning | Home | 0 | No data | NA |

| Home (indirect) | 1 | 1.30 (0.58–2.90) | Very Low | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 1 | 2.86 (1.09–7.55) | Low | |

| Hospital | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home | 1 | Significantb | Low | |

| Emergency | Home (indirect) | 1 | Nonsignificantb | Low |

| Department Visits | Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA |

| Comprehensive | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 1 | Nonsignificantb | Low | |

| Hospital Admission | Hospital | 0 | No data | NA |

| Home | 1 | 0.39 (0.24–0.62) | Low | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | 0.90 (0.42–1.89) | Moderate | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 1 | 0.84 (0.34–2.03) | Low | |

| Intensive Care Unit Admission | Hospital | 1 | Significantb | Low |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Hospital Length of Stay | Hospital | 4 | Nonsignificantb | Moderate |

| Home | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Home (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive (indirect) | 0 | No data | NA | |

| Comprehensive | 1 | Nonsignificantb | Moderate | |

| Comprehensive, Early Start | 0 | No data | NA |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; NA, not available; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Direct contact unless otherwise noted.

Odds ratio value not available.

Conclusions

In our systematic review of team-based end-of-life care, we looked at care provided by teams that included, at minimum, a physician and a nurse, at least one of whom was specialized or experienced in end-of-life health care. Team services included symptom management, psychosocial care, development of patient care plans, end-of-life care planning, and coordination of care. The following findings apply to models of team-based end-of-life care used to deliver care to people with an estimated survival of up to 24 months.

Comprehensive Team-Based Model

There is moderate-quality evidence that a comprehensive team-based model with direct patient contact significantly:

improves patient QOL, symptom management, and patient and informal caregiver satisfaction;

increases the patient's likelihood of dying at home;

decreases the patient's likelihood of dying in a nursing home; and

has no impact on hospital admissions or hospital length of stay.

Hospital Team-Based Model

There is moderate-quality evidence that a hospital team-based model with direct patient contact has no impact on length of hospital stay. There is low-quality evidence that this model significantly reduces ICU admissions.

Home Team-Based Model

There is low-quality evidence that a home team-based model with direct patient contact:

significantly increases patient satisfaction, and increases the patient's likelihood of dying at home; and

significantly decreases emergency department visits and hospital admissions.

Team Membership and Services

Team membership includes at minimum a physician and nurse, one of whom is specialized or experienced in end-of-life health care.

Team services include:

symptom management

psychosocial care

development of patient care plans

end-of-life care planning

coordination of care

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Sue MacLeod, BA

Medical Information Services

Corinne Holubowich, BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Health Quality Ontario's Expert Advisory Panel on End-of-Life Care

| Panel Member | Affiliation(s) | Appointment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Panel Co-Chairs | ||

| Dr Robert Fowler | Sunnybrook Research Institute University of Toronto |

Senior Scientist Associate Professor |

| Shirlee Sharkey | St. Elizabeth Health Care Centre | President and CEO |

| Professional Organizations Representation | ||

| Dr Scott Wooder | Ontario Medical Association | President |

| Health Care System Representation | ||

| Dr Douglas Manuel | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute University of Ottawa |

Senior Scientist Associate Professor |

| Primary/Palliative Care | ||

| Dr Russell Goldman | Mount Sinai Hospital, Tammy Latner Centre for Palliative Care | Director |

| Dr Sandy Buchman | Mount Sinai Hospital, Tammy Latner Centre for Palliative Care Cancer Care Ontario University of Toronto |

Educational Lead Clinical Lead QI Assistant Professor |

| Dr Mary Anne Huggins | Mississauga Halton Palliative Care Network; Dorothy Ley Hospice |

Medical Director |

| Dr Cathy Faulds | London Family Health Team | Lead Physician |

| Dr José Pereira | The Ottawa Hospital University of Ottawa |

Professor, and Chief of the Palliative Care program at The Ottawa Hospital |

| Dean Walters | Central East Community Care Access Centre | Nurse Practitioner |

| Critical Care | ||

| Dr Daren Heyland | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit Kingston General Hospital |

Scientific Director |

| Oncology | ||

| Dr Craig Earle | Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Cancer Care Ontario |

Director of Health Services Research Program |

| Internal Medicine | ||

| Dr John You | McMaster University | Associate Professor |

| Geriatrics | ||

| Dr Daphna Grossman | Baycrest Health Sciences | Deputy Head Palliative Care |

| Social Work | ||

| Mary-Lou Kelley | School of Social Work and Northern Ontario School of Medicine Lakehead University |

Professor |

| Emergency Medicine | ||

| Dr Barry McLellan | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | President and Chief Executive Officer |

| Bioethics | ||

| Robert Sibbald | London Health Sciences Centre University of Western Ontario |

Professor |

| Nursing | ||

| Vicki Lejambe | Saint Elizabeth Health Care | Advanced Practice Consultant |

| Tracey DasGupta | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Director, Interprofessional Practice |

| Mary Jane Esplen | De Souza Institute University of Toronto |

Director Clinician Scientist |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Database: EBM Reviews – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 〈2005 to August 2013〉, EBM Reviews – ACP Journal Club 〈1991 to September 2013〉, EBM Reviews – Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects 〈3rd Quarter 2013〉, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 〈September 2013〉, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Methodology Register 〈3rd Quarter 2012〉, EBM Reviews – Health Technology Assessment 〈3rd Quarter 2013〉, EBM Reviews – NHS Economic Evaluation Database 〈3rd Quarter 2013〉, Embase 〈1980 to 2013 Week 39〉, Ovid MEDLINE(R) 〈1946 to September Week 4 2013〉, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations 〈October 01, 2013〉

Literature Search – End of Life Mega Analysis – Models of Care

Search date: October 4, 2013

Databases searched: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process, Embase, All EBM Databases (see below), CINAHL

Limits: 2000-current; English

Filters: none

Search Strategy:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Terminal Care/ | 86143 |

| 2 | exp EoL Care/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 41169 |

| 3 | exp EoL therapy/ use emez | 60776 |

| 4 | exp Terminally Ill/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 5628 |

| 5 | exp terminally ill patient/ use emez | 5887 |

| 6 | exp terminal disease/ use emez | 4482 |

| 7 | exp dying/ use emez | 5626 |

| 8 | ((End adj2 life adj2 care) or EoL care or (terminal∗ adj2 (care or caring or ill∗ or disease∗)) or palliat∗ or dying or (Advanced adj3 (disease∗ or illness∗)) or end stage∗).ti,ab. | 335882 |

| 9 | or/1-8 | 429328 |

| 10 | exp Models, Organizational/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 15237 |

| 11 | exp Models, Nursing/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 11080 |

| 12 | exp process model/ use emez | 5434 |

| 13 | exp “Continuity of Patient Care”/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 15196 |

| 14 | exp Patient Care Team/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 55228 |

| 15 | exp patient care planning/ use emez | 26684 |

| 16 | exp “Delivery of Health care, Integrated”/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 8707 |

| 17 | exp integrated health care system/ use emez | 6645 |

| 18 | ((care or service) adj2 delivery adj2 (model∗ or system∗)).ti,ab. | 10537 |

| 19 | (((care or deliver∗ or service or end of life or palliat∗ or specialist∗ or location or hospice∗ or hospital∗ or home) adj (model or models)) or (hub and spoke) or ((multi?disciplin∗ or interdisciplin∗) adj2 (palliat∗ or team∗)) or residential hospice∗ or regionalization or EoL care unit module∗ or special∗ EoL care∗).ti,ab. | 49712 |

| 20 | or/10-19 | 188034 |

| 21 | 9 and 20 | 9177 |

| 22 | limit 21 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,ACP Journal Club,DARE,CCTR,CLCMR; records were retained] | 7993 |

| 23 | limit 22 to yr=”2000 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] | 6251 |

| 24 | limit 23 to yr=”2000 – 2007” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] | 2590 |

| 25 | remove duplicates from 24 | 1833 |

| 26 | limit 23 to yr=”2008 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] | 3667 |

| 27 | remove duplicates from 26 | 2680 |

| 28 | 25 or 27 | 4507 |

CINAHL

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Terminal Care+”) | 38,902 |

| S2 | (MH “EoL Care”) | 19,664 |

| S3 | (MH “Terminally Ill Patients+”) | 7,658 |

| S4 | ((End N2 life N2 care) or EoL care or (terminal∗ N2 (care or caring or ill∗ or disease∗)) or palliat∗ or dying or (advanced N3 (disease∗ or illness∗)) or end stage∗) | 52,151 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | 60,134 |

| S6 | (MH “Nursing Models, Theoretical+”) | 10,292 |

| S7 | (MH “Continuity of Patient Care+”) | 10,843 |

| S8 | (MH “Multidisciplinary Care Team+”) | 25,019 |

| S9 | (MH “Health care Delivery, Integrated”) | 5,213 |

| S10 | ((care or service) N2 delivery N2 (model∗ or system∗)) | 3,540 |

| S11 | (((care or deliver∗ or service or end of life or palliat∗ or specialist∗ or location or hospice∗ or hospital∗ or home) N1 (model or models)) or (hub and spoke) or ((multidisciplin∗ or multi-discplin∗ or interdisciplin∗) N2 (palliat∗ or team∗)) or residential hospice∗ or regionalization or EoL care unit module∗ or special∗ EoL care∗) | 37,428 |

| S12 | S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 | 61,655 |

| S13 | S5 AND S12 | 3,965 |

| S14 | S5 AND S12 | 3,965 |

| S15 | S5 AND S12 Limiters – Published Date: 20000101-20131231; English Language | 3,243 |

Appendix 2: Evidence Quality Assessment

Table A1:

AMSTAR Scores of Included Systematic Reviews

| Author, Year | AMSTAR Scorea | (1) Provided Study Design | (2) Duplicate Study Selection | (3) Broad Literature Search | (4) Considered Status of Publication | (5) Listed Excluded Studies | (6) Provided Characteristics of Studies | (7) Assessed Scientific Quality | (8) Considered Quality in Report | (9) Methods to Combine Appropriate | (10) Assessed Publication Bias | (11) Stated Conflict of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gomes et al (9) | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Higginson et al (14) | 8 | ✓ | Xc | ✓ | ✓ | Xb | Xb | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Details of AMSTAR score are described in Shea at al. (11) Maximum possible score is 11.

Information not provided.

Cannot answer.

Table A2:

GRADE Evidence Profile for Comparison of Team-Based Model of End-of-Life Care and Usual Care

| Number of Studies (Design) | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Quality of Life (Hospital Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Gade et al (19) Hanks et al (20) |

Very serious limitations (−2)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitationsb | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Patient Quality of Life (Comprehensive Model, Indirect Contact) | |||||||

| Mitchell et al (22) | Very serious limitations (−2)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitationsb | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Patient Quality of Life (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Jordhoy et al (21) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Patient Quality of Life (Comprehensive Model, Direct and Early Contact) | |||||||

| Temel et al (23) Zimmermann et al (24) |

Serious limitations (−1)c | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Symptom Management (Hospital Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Gade et al (19) Hanks et al (20) |

Serious limitations (−1)c | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)d | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Symptom Management (Comprehensive Model, Direct and Early Contact) | |||||||

| Zimmermann et al (24) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Patient Satisfaction (Home Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Brumley et al (17) | Very serious limitations (−2)e | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Patient Satisfaction (Comprehensive Model, Direct and Early Contact) | |||||||

| Zimmermann et al (24) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Informal Caregiver Satisfaction (Hospital Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Cheung et al (18) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)f | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Informal Caregiver Satisfaction (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Jordhoy et al (21) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Home Death (Home Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Brumley et al (17) | Very serious limitations (−2)g | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Home Death (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Jordhoy et al (21) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Nursing Home Death (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Jordhoy et al (21) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Advance Care Planning (Home Model, Indirect Contact) | |||||||

| Aiken et al (16) | Very serious limitations (−2)h | n/a | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)i | n/a | n/a | ⊕ Very Low |

| Advance Care Planning (Hospital Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Ahronheim et al (15) Gade et al (19) |

Serious limitations (−1)c | Serious limitations (−1)j | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)i | n/a | n/a | ⊕ Very Low |

| Advance Care Planning (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact, Early Contact) | |||||||

| Temel et al (23) | Serious limitations (−1)k | n/a | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)i | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Emergency Department Visits (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact, Early Contact) | |||||||

| Temel et al (23) | Serious limitations (−1)l | n/a | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)f | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Emergency Department Visits (Home Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Brumley et al (17) | Very serious limitations (−2)e | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Emergency Department Visits (Home Model, Indirect Contact) | |||||||

| Aiken et al (16) | Very serious limitations (−2)m | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Hospital Admissions (Home Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Brumley et al (17) | Very serious limitations (−2)e | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Hospital Admissions (Comprehensive Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Jordhoy et al (21) | Serious limitations (−1)c | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Hospital Admissions (Comprehensive Model, Direct and Early Contact) | |||||||

| Temel et al (23) | Serious limitations (−1)l | n/a | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (−1)f | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |

| ICU Admissions (Hospital Model, Direct Contact) | |||||||

| Gade et al (19) | Very serious limitations (−2)n | n/a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | n/a | n/a | ⊕⊕ Low |