Introduction

Around one-tenth of the adults in Canada are affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD), which is defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.1 Early recognition of CKD is important, since timely implementation of lifestyle and pharmacological interventions can prevent it or slow its progression.2-4 Such interventions can also reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD)5,6—the primary cause of death in these patients.7 However, patients with CKD are often not recognized and do not receive optimal treatment because of complexities in care and failure to disseminate best practices.8-10

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD clinical practice guidelines provide evidence for the evaluation and management of CKD.11 While clinical practice guidelines summarize evidence and provide recommendations, they are often difficult to apply in routine daily clinical activities. Clinical pathways are often derived from clinical practice guidelines but differ by providing more explicit and practical information about the sequence, timing and provision of interventions.12 A clinical pathway can be an effective tool to increase uptake of evidence-based health care by pharmacists and other primary care professionals in the community, who care for the majority of patients with CKD.13-15

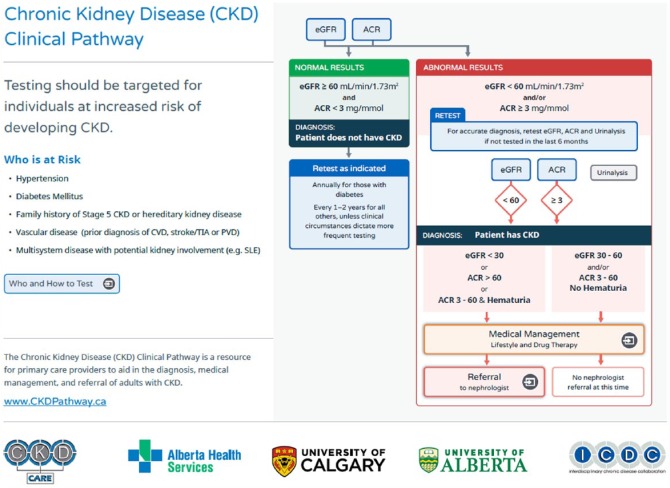

Pharmacists in Canada have an expanding scope of practice; pharmacists can order laboratory tests, adapt new prescriptions, perform therapeutic substitutions, issue prescriptions for continuity of care and prescribe in emergency situations.16 In Alberta, pharmacists who have Additional Prescribing Authorization can prescribe at initial access or manage ongoing therapy based on their own assessment or in collaboration with another regulated health care professional.17 An integral part of pharmacists’ practice is working collaboratively and communicating with physicians and other health care providers.17 As pharmacists’ expanded scope of practice develops,16 tools such as the CKD Clinical Pathway (Figure 1) can assist pharmacists to implement evidence-based guidelines into their daily practice. This manuscript provides an overview of the clinical pathway for diagnosis, management and referral of adults with CKD and its potential clinical use for pharmacists.

Figure 1.

Overview of the adult CKD Clinical Pathway

Development of the adult CKD Clinical Pathway

The CKD Clinical Pathway is an online tool/guideline modeled after the successful National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical pathways (http://pathways.nice.org.uk). It was developed by a team of stakeholders that included pharmacists, nephrologists, primary care physicians, nurses, other health care professionals, IT specialists, web developers and designers. Usability and heuristic testing with primary care professionals has been completed, and the CKD Clinical Pathway has been available online since November 4, 2014 (www.CKDpathway.ca). The content in the CKD Clinical Pathway is evidence based and uses international and national guidelines, including the KDIGO CKD guidelines,11 KDIGO Lipid guidelines,18 C-CHANGE,19 Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) guidelines,20 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Lipid and Antiplatelet guidelines21,22 and Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines.23 This ensures that the recommendations are relevant and harmonized across Canada. Some of the content, such as the specialist referral form, is tailored to practice in Alberta. Users of the pathway should be aware that their local laboratory may report different reference ranges and units of measure than the laboratories in Alberta. Currently, laboratories in Alberta report estimated GFR using the CKD-EPI equation.24

Components of the adult CKD Clinical Pathway

The CKD Clinical Pathway contains 3 main sections: targeted screening and identification of patients with CKD, management of CKD and criteria for referring those patients to nephrologists.

Targeted screening and identification

Targeted screening (also called case finding) of those at risk of developing CKD is recommended, since population-based screening is not cost effective. Targeted screening is directed at patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, family history of CKD or hereditary kidney disease, vascular disease or multisystem disease with potential kidney involvement (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, myeloma or other autoimmune diseases). Individuals who are at risk of CKD should be screened using serum creatinine, estimated GFR, urinalysis and albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR).11 A urinalysis is included to detect hematuria, one of the variables considered in the criteria for nephrologist referral. However, a urinalysis is not sensitive enough to reliably detect and quantify proteinuria; therefore, a random urine ACR performed on an early morning urine sample is preferred.11 A urine ACR has greater sensitivity for low levels of proteinuria compared to a urine protein-creatinine ratio (PCR), and it measures the most common type of protein present in the urine associated with the most common causes of CKD—hypertension and diabetes.11 ACR is a “spot” test, and therefore specimen collection is much easier for patients compared with 24-hour urine collection. Also, ACR is not affected by dilution or concentration of the urine.11

In patients with a new finding of abnormal eGFR or ACR, these tests should be repeated within 2 to 4 weeks to exclude causes of transient abnormalities and acute deterioration of kidney function (e.g., acute kidney injury). There is no need to retest if the patient had a previous abnormal eGFR or ACR within the past 6 months. The values of the tests can be entered into the pathway to determine whether the results meet the criteria for the diagnosis of CKD and to provide recommendations on further screening, management and referral.

Management

The management section of the CKD Clinical Pathway focuses on interventions that can decrease or slow the progression of kidney disease and reduce vascular risk (see Table 1). It provides guidance on making lifestyle recommendations; managing comorbid medical conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, and the targets recommended for patients with CKD; managing albuminuria and adverse effects from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARB); managing vascular risk and recommended dosing for statin medications; identifying potentially nephrotoxic medications; and providing guidance for renal dose adjustments for common medications. The CKD Clinical Pathway provides management recommendations based on the presence or absence of diabetes.

Table 1.

Targets for the management of CKD

| Lifestyle changes |

| Hypertension |

| Diabetes |

| Managing albuminuria |

| Vascular risk reduction |

| Identifying potentially nephrotoxic medications |

| Renal dose adjustments |

Lifestyle

All patients who have CKD benefit from implementation of lifestyle changes such as a healthy body mass index (BMI <25 kg/m2), at least 150 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, tobacco cessation and a low-salt diet.19 As CKD progresses, patients may require potassium, phosphate and protein dietary restrictions.11 Several patient information teaching tools on these topics are integrated into the pathway.

Blood pressure

The target blood pressure for patients with CKD is less than 140/90 mmHg. Patients with both CKD and diabetes should target a blood pressure of less than 130/80 mmHg.11,23 Combination antihypertensive therapy may be required for most patients in order to achieve these targets.19 The combination of an ACEi and an ARB is no longer recommended for most patients with CKD due to lack of benefit and increased risk of adverse effects.19,25

Protein in the urine

The KDIGO CKD guidelines emphasize the importance of albuminuria in defining and managing CKD. These changes are significant, as albuminuria is associated with increased mortality, vascular events and kidney failure, even in patients with “normal” kidney function.26-29 Further, identification and management of patients with albuminuria can improve patient-relevant outcomes.2,30 Patients who have CKD and diabetes should receive an ACEi or ARB, unless contraindicated, to reduce the microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes.31 Albuminuria in patients with diabetes is diagnostic for the presence of CKD and predictive of CKD progression.11,20 Patients who have CKD without diabetes should receive an ACEi or ARB if they have an ACR greater than 30 mg/mmol and no contraindications.11 When an ACEi or ARB is initiated, it can cause a 5% to 30% reversible reduction in GFR and/or a 0.5 mmol/L increase in serum potassium.32 However, an ACEi or ARB can be prescribed safely in all stages of CKD and should not be intentionally avoided.32 The CKD Clinical Pathway provides practical guidance on managing hyperkalemia and other potential adverse effects.

Vascular risk

Patients who have CKD are at increased risk of vascular events.7,33 Although no validated vascular risk calculators are available for use specifically in these patients,11 existing risk calculators such as Framingham Risk Score are commonly used and widely accepted (although they tend to underestimate the risk in patients with CKD).11,33 While several medication classes can lower cholesterol levels, only regimens that include a statin have been proven to reduce vascular risk in patients who have CKD.18 All patients who have diabetes and CKD should receive statin therapy to decrease their vascular risk regardless of cholesterol levels or age. Patients who have CKD without diabetes should receive statin therapy if they are over the age of 50 years, have coronary artery disease, have experienced an ischemic stroke or have an estimated 10-year vascular risk greater than 10%.18 According to the updated KDIGO 2013 Lipid Guidelines, no routine monitoring of cholesterol levels is required unless the result will change the course of therapy.18 The “treat-to-target” strategy has not been proven beneficial in any clinical trial.18 In addition, the association between low-density lipoprotein and clinical outcomes is weaker in patients with CKD and does not reliably predict their prognosis.18 The “treat-and-forget” strategy should be used at a dose of statin that is known to be safe and effective in patients with CKD,18 as outlined in the CKD Clinical Pathway. Recommended doses for various statins are included in the pathway.

Antiplatelet drugs

The use of antiplatelet drugs (acetylsalicylic acid [ASA], clopidogrel) is not recommended for primary prevention of vascular disease in patients who have CKD.11 Low-dose ASA can be used safely in patients who have established vascular disease such as acute coronary syndrome, prior myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease (high-risk patients with low bleeding risk).11 The risk of bleeding in patients with CKD may be increased, but the benefits appear to outweigh the risks.11,34

Nephrotoxic drugs

The CKD Clinical Pathway includes a list of medications that have been associated with causing nephrotoxicity through a variety of mechanisms.35 Risk factors for drug-induced nephropathy include age over 60 years, underlying renal insufficiency, dehydration, exposure to multiple nephrotoxic medications, diabetes, heart failure and sepsis.36 At the first sign of reduced kidney function, the patient’s comprehensive medication list should be reviewed to identify potentially nephrotoxic medications.36 Each situation requires an individualized assessment, and a risk-versus-benefit approach can be helpful to determine the course of action. Most episodes of drug-induced nephropathy are reversible provided that the decreased renal function is recognized early and the offending medication is discontinued.36 General measures to be considered include switching to an alternate medication that is not associated with nephrotoxicity, correcting risk factors for nephrotoxicity, assessing baseline renal function before initiating therapy, adjusting the dose of medications for renal function and avoiding nephrotoxic drug combinations.36

Drug information

Despite the availability of renal drug dosing information, inappropriate dosing occurs frequently, causing many preventable adverse drug events.37,38 The CKD Clinical Pathway provides guidance for renal dose adjustments for common medications used in primary care practice. This list is comprehensive but not exhaustive and should be considered as a useful starting place. Other potential sources of information include tertiary references such as LexiComp, Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties, Micromedex, Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure or the Renal Drug Handbook. Many review articles have been published on this subject.39

Referral

The CKD Clinical Pathway provides criteria detailing which patients should be referred to a nephrologist. Awareness of situations requiring urgent or emergent referral would be helpful for pharmacists as they will undoubtedly identify patients meeting these criteria.

Other features

The CKD Clinical Pathway has a resource page that links to more information on classification of CKD, prognosis and frequency of testing, a Framingham risk calculator, management of elevated serum potassium and clinical practice guidelines used in developing the CKD Clinical Pathway.

Clinical use of the CKD Clinical Pathway

As pharmacists continue to embrace their expanded scope of practice, there is also an increased need for practical tools and guidelines that can help guide clinical decision making. The CKD Clinical Pathway is available at the point of care for any pharmacist with access to the Internet. This allows timely application of evidence-based recommendations. While the pathway has portions that are tailored to practice in Alberta, the main content is applicable to any patient with CKD regardless of locale. The CKD Clinical Pathway is intended to be used by any health care provider, including physicians, nurses and pharmacists, and encourages interdisciplinary collaboration to provide optimal care for patients.

The online adult CKD Clinical Pathway is a new and innovative guideline designed to improve the care provided to patients with CKD. As far as the working group is aware, this is the first implementation of such an online tool in Canada. It contains evidence-based recommendations in an easy-to-follow format. It can be accessed at www.ckdpathway.ca. For more information or to provide feedback, please contact ckdpathway@ucalgary.ca. ■

Footnotes

Author Contributions:All authors contributed to CKD pathway design, critical review of the manuscript and approval of the final version submitted for publication. C. Curtis wrote the final draft of the manuscript. C. Curtis, C. Balint, Y. Al Hamarneh, K. McBrien and W. Jackson contributed to CKD pathway content and design and were final reviewers of all CKD pathway content. R.T. Tsuyuki was responsible for research design and methodology. M. Donald, K. McBrien and W. Jackson were responsible for design and implementation of the CKD pathway. B. Hemmelgarn initiated the project; obtained funding; was responsible for design, methodology and implementation of the CKD pathway; supervised the project; and was a final reviewer of CKD pathway content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:Financial support for this research was received from Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions, the Government of Canada—Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration.

References

- 1. Arora P, Vasa P, Brenner D, et al. Prevalence estimates of chronic kidney disease in Canada: results of a nationally representative survey. CMAJ 2013;185:E417-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:73-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:851-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright JT, Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK Trial. JAMA 2002;288:2421-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tonelli M, Moye L, Sacks FM, et al. Effect of pravastatin on loss of renal function in people with moderate chronic renal insufficiency and cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:1605-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mann JFE, Gerstein HC, Pogue J, et al. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and the impact of ramipril: the HOPE randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:629-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:1307-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shlipak M, Heidenreich P. Association of renal insufficiency with treatment and outcomes after myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:555-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tonelli M, Bohm C, Pandeya S, Gill J. Cardiac risk factors and the use of cardioprotective medications in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;37:484-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stevens L, Fares G, Fleming J. Low rates of testing and diagnostic codes usage in a commercial clinical laboratory: evidence for lack of physician awareness of chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:2439-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013;3:1-150. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, et al. Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3):CD006632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of integrated care pathways: what works, for whom, in which circumstances? Int J Evid Based Healthc 2009;7:61-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sulch D, Perez I, Melbourn A, Kalra L. Randomized controlled trial of integrated (managed) care pathway for stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2000;31:1929-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cunningham S, Logan C, Lockerbie L, et al. Effect of an integrated care pathway on acute asthma/wheeze in children attending hospital: cluster randomized trial. J Pediatr 2008;152:315-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacists’ expanded scope of practice in Canada. 2014. Available: www.pharmacists.ca/index.cfm/pharmacy-in-canada/scope-of-practice-canada/ (accessed December 5, 2014).

- 17. Alberta College of Pharmacists. The health professional’s guide to pharmacist prescribing. 2012. Available: https://pharmacists.ab.ca/sites/default/files/HPGuidePrescribing.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

- 18. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Lipid Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for lipid management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013;3:1-305. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tobe S, Stone J, Brouwers M, et al. Harmonization of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: the C-CHANGE Initiative. CMAJ 2011;183:1135-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Introduction. Can J Diabetes 2013; 37(Suppl 1):S1-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanguay J-F, Bell AD, Ackman ML, et al. Focused 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:1334-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Hegele RA, et al. 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:151-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hackam DG, Quinn RR, Ravani P, et al. The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:528-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. AHS Laboratory Services. Use of the CKD-EPI equation for reporting estimated glomerular filtration rate. 2013. Available: www.albertahealthservices.ca/LabServices/wf-lab-bulletin-use-of-ckd-epi-equation-egfr-final.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

- 25. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:2073-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, et al. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 2010;303:423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Tonelli M. Early recognition and prevention of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2010;375:1296-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Using proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate to classify risk in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:12-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strippoli GFM, Craig M, Deeks JJ, et al. Effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists on mortality and renal outcomes in diabetic nephropathy: systematic review. BMJ 2004;329:828-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, et al. The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: a KDIGO controversies conference report. Kidney Int 2011;80:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) management in general practice. 2nd ed. Melbourne (AU): Kidney Health Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Said S, Hernandez GT. The link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. J Nephropathol 2014;3:99-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jardine MJ, Ninomiya T, Perkovic V, et al. Aspirin is beneficial in hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease: a post-hoc subgroup analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:956-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pannu N, Nadim MK. An overview of drug-induced acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2008;36(4 Suppl):S216-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naughton C. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am Fam Physician 2008;78:743-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Farag A, Garg AX, Li L, Jain AK. Dosing errors in prescribed antibiotics for older persons with CKD: a retrospective time series analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63:422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aronoff GR, Aronoff JR. Drug prescribing in kidney disease: can’t we do better? Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63:382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Munar M, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician 2007;75:1487-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]