Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Longitudinal studies have linked the systemic inflammatory markers interleukin 6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) with the risk of developing heart disease and diabetes mellitus, which are common comorbidities for depression and psychosis. Recent meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies have reported increased serum levels of these inflammatory markers in depression, first-episode psychosis, and acute psychotic relapse; however, the direction of the association has been unclear.

OBJECTIVE

To test the hypothesis that higher serum levels of IL-6 and CRP in childhood would increase future risks for depression and psychosis.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)is a prospective general population birth cohort study based in Avon County, England. We have studied a subsample of approximately 4500 individuals from the cohort with data on childhood IL-6 and CRP levels and later psychiatric assessments.

MEASUREMENT OF EXPOSURE

Levels of IL-6 and CRP were measured in nonfasting blood samples obtained in participants at age 9 years.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Participants were assessed at age 18 years. Depression was measured using the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised (CIS-R) and Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ), thus allowing internal replication; psychotic experiences (PEs) and psychotic disorder were measured by a semistructured interview.

RESULTS

After adjusting for sex, age, body mass index, ethnicity, social class, past psychological and behavioral problems, and maternal postpartum depression, participants in the top third of IL-6 values compared with the bottom third at age 9 years were more likely to be depressed (CIS-R) at age 18 years (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.55; 95% CI, 1.13-2.14). Results using the MFQ were similar. Risks of PEs and of psychotic disorder at age 18 years were also increased with higher IL-6 levels at baseline (adjusted OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.01-3.28; and adjusted OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 0.88-6.22, respectively). Higher IL-6 levels in childhood were associated with subsequent risks of depression and PEs in a dose-dependent manner.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Higher levels of the systemic inflammatory marker IL-6 in childhood are associated with an increased risk of developing depression and psychosis in young adulthood. Inflammatory pathways may provide important new intervention and prevention targets for these disorders. Inflammation might explain the high comorbidity between heart disease, diabetes mellitus, depression, and schizophrenia.

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide.1 It affects approximately 16% of Americans during their lifetime, with approximately 25% of these cases beginning before age 20 years.2,3 Psychotic disorders (including schizophrenia) are some of the most enduring neuropsychiatric illnesses, with a lifetime risk of 1% to 2% in the United States.4 Globally, schizophrenia is an important cause of disability among young people and is associated with premature death, largely from heart disease.5,6 Longitudinal studies7-11 have linked higher levels of circulating inflammatory markers such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP), with subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart disease. These chronic physical conditions often occur concomitantly with depression and psychotic disorders12,13 and may share pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Mechanisms involving monoamines underpin contemporary pathophysiologic explanations and drug therapy for depression and psychosis.14,15 However, heterogeneity in presentation, course, and treatment responses suggest additional mechanisms. Supported by several observations, cytokine-mediated communication between the immune system and the brain has recently been implicated in the pathogenesis of these disorders.16,17 Animal models16 suggest that systemic inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, can communicate with the brain. An increase in cytokine serum levels may lead to decreased availability of serotonin and other neurotransmitters, activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and increased oxidative stress in the brain.16,18 These effects could contribute to the impaired mood, cognition, and perception seen in depression and psychosis. Indeed, injection of IL-6 in healthy volunteers induces low mood, anxiety, and reduced cognitive performance.19 Epidemiologic studies20-23 have linked early-life infection and autoimmune disease with subsequent depression and psychosis in adult life. Currently used antidepressants14 and antipsychotics17 have anti-inflammatory properties. Finally, meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies have reported increased serum IL-6 and CRP levels in depression,24 first-episode psychosis,17 and acute psychotic relapse.17 However, there have been very few longitudinal studies of inflammatory markers and either psychosis25 or depression, and the inconsistent results may be the result of methodologic differences.26-28

Using data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), a general population birth cohort, we report a longitudinal study of serum IL-6 and CRP levels at age 9 years and the risks for depression or psychosis at age 18 years. We predicted that higher levels of these inflammatory markers at baseline would be associated with subsequent risks for depression and psychosis.

Methods

Description of Cohort

The ALSPAC birth cohort comprises 14 062 live births from women residing in Avon County, a geographically defined region in southwest England, with expected dates of delivery between April 1991 and December 1992 (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/). Parents completed regular postal questionnaires about all aspects of their child’s health and development from birth. From age 7 years, the children attended an annual assessment clinic during which they participated in various face-to-face interviews and physical tests.

The study received ethics approval from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee and local research ethics committees. All participants provided written informed consent. There was no financial compensation.

The risk set for the present study included 4585 individuals. Parents gave informed consent for venipuncture in 7236 children aged 9 years. This was successfully completed on 5880 children; 5076 provided enough blood to measure IL-6 and CRP levels. We were interested in baseline innate immune activity as reflected by inflammatory marker levels in healthy individuals. Thus, we excluded 491 children who reported an infection at the time of blood collection or in the preceding week because acute infection sharply increases IL-6 and CRP levels, which return to baseline after illness subsides. Of the risk set, 2453 and 2528 individuals, respectively, attended assessments for depression and psychosis at age 18; our main analyses were based on these samples. We subsequently repeated the analyses after imputation of missing outcome data (n = 4415).

Laboratory Methods

Blood samples were collected from nonfasting participants and were immediately spun and frozen at −80°C. Inflammatory markers were assayed in 2008 after a median of 7.5 years in storage with no previous freeze-thaw cycles during this period. Interleukin 6 was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems), and high-sensitivity CRP was measured by automated particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay (Roche) (eMethods in the Supplement). All interassay coefficients of variation were less than 5%. No other inflammatory markers were measured.

Psychiatric Measures

Depression at Age 18

Depression was measured in 2 ways—interview and questionnaire—so as to allow internal replication. The computerized version of the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R) was self-administered by cohort participants in assessment clinics. The CIS-R is a widely used standardized tool for measuring depression and anxiety in community samples.29 It includes core symptoms of depression based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, criteria and gives a total depression score of 0 to 21 comprising symptom scores for depression, depressive thoughts, fatigue, concentration, and sleep problems. Thus, the total depression score reflects the severity of depressive symptoms experienced in the past week. We used this continuous variable as the main outcome to make full use of variation in symptoms. We also created a binary outcome: individuals with scores of 7 or more were considered as cases of depression. In addition, we used 2 alternative cutoff scores (≥8 and ≥9).

Depression was also measured using the short version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ)30 (eMethods in the Supplement), which allowed us to check the internal consistency of the primary analyses using CIS-R.

Psychotic Outcomes at Age 18

Psychotic experiences (PEs) were identified through the face-to-face, semistructured Psychosis-Like Symptom Interview31 (PLIKSi) conducted by trained psychology graduates in assessment clinics and were coded according to the definitions and rating rules for the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, Version 2.0.32 The PLIKSi has good interrater and test-retest reliability (both κ= 0.8).31 Psychotic experiences covering the 3 main domains of positive psychotic symptoms occurring since age 12 were elicited: hallucinations (visual and auditory), delusions (spied on, persecuted, thoughts read, reference, control, grandiosity, and other), and thought interference (insertion, withdrawal, and broadcasting).

After cross-questioning, interviewers rated PEs as not present, suspected, or definitely psychotic. For suspected or definite PEs, interviewers also recorded the frequency; effect on affect, social function, and educational/occupational function; help seeking; and attributions, such as fever, hypnopompic/hypnogogic state, or drugs. Measures were taken to ensure the quality of the rating process (eMethods in the Supplement).

Cases of PEs were defined as individuals with definite PEs. Cases of psychotic disorder, a more restricted phenotype, were defined as individuals with definite PEs that were not attributable to the effects of sleep or fever and when the PE (1) occurred at least once per month over the past 6 months and (2) caused severe distress, had a very negative effect on social/occupational function, or led to help seeking from a professional source.31

Psychological and Behavioral Problems at Age 7

Mothers completed the parental version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) when the study child was aged 7. The SDQ is an age-appropriate, valid, and reliable tool for measuring psychological and behavioral problems in young children.33 It measures difficulties in 4 domains (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems) and gives a total difficulties score of 0 to 40. Childhood psychological and behavioral problems are associated with various future psychiatric outcomes, including psychosis and depression.34 Given that no assessment was undertaken for psychosis or depression before measurement of IL-6 levels at age 9, we controlled for this more general measure of psychological and behavioral problems using the SDQ at age 7.

Statistical Analysis

We used all participants who did not meet the particular case definitions described above as the comparison group. Thus, we included cases of PEs and psychotic disorder in the comparison group for depression and vice versa. The sample was divided into thirds according to tertiles of IL-6 and CRP distributions in the entire risk set at age 9. Inflammatory marker levels and the total depression scores were analyzed as both continuous and categorical variables.

We used logistic regression to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for psychiatric outcomes at age 18 among individuals in the middle and top thirds compared with the bottom third of inflammatory marker distribution at age 9. Linearity of association was tested by inspection of the ORs over the thirds of the inflammatory marker distribution. Using IL-6 levels as a continuous variable (z-transformed values), the ORs for psychiatric outcomes were calculated per SD increase in IL-6 levels; nonlinearity was examined by the inclusion of a quadratic term (IL-62) within these logistic regression models. Additionally for depression, linear regression calculated the co-efficient for an SD increase in total CIS-R depression score at age 18 for each SD increase in IL-6 at age 9, using both depression and IL-6 as continuous variables (z-transformed values). All regression models were adjusted for age at follow-up, body mass index (BMI) at baseline, sex, ethnicity, father’s social class, SDQ score at age 7, and maternal Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score at 8 weeks postpartum.

We examined whether the direction of causality was childhood psychological problems (measured as SDQ score at age 7) leading to both increased IL-6 at age 9 and risk of psychiatric outcomes at age 18 rather than being an independent effect of IL-6 on later psychiatric risk. First, we separately assessed the associations between the SDQ score and IL-6 levels (linear regression) as well as psychiatric outcomes (logistic regression). Next, both the SDQ score and IL-6 values were included in the same regression model as predictors of psychiatric outcomes at age 18; if there was no direct effect of IL-6 on later psychiatric risk, we expected that the OR for psychiatric outcome for IL-6 would attenuate substantially.

To test whether sex modified any association between IL-6 and psychiatric outcomes, we tested for an interaction between IL-6 and sex in the logistic regression models of IL-6 and the binary outcomes of CIS-R depression, PE, and psychotic disorder.

Imputation of Missing Outcome Data

Of the 4585 individuals with inflammatory marker data at age 9 years, 4415 had provided data on depression and PEs in clinics or by questionnaires at some point between ages 10 and 16 years. For this sample of 4415, we used the depression, PE, and sociodemographic data to predict missing depression and PE information at age 18 with multiple imputation techniques used by the ice command in Stata, version 12 (Stata Corp) (eMethods in the Supplement).35

Results

Baseline Comparisons and Characteristics of the Sample

Higher serum IL-6 levels at age 9 were associated with female sex, higher BMI, and father’s manual occupation (Table 1). Similar associations were also observed for CRP. After controlling for sex and BMI, IL-6 and CRP were significantly correlated (r = 0.04; P < .001).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Sample.

| Distribution of IL-6 at Age 9 ya |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Bottom Third | Middle Third | Top Third | P Valueb |

| Total No. of participants | 1590 | 1525 | 1470 | |

|

| ||||

| Age at outcome, mean (SD), y | 17.8 (0.36) | 17.8 (0.38) | 17.8 (0.35) | .32 |

|

| ||||

| Male sex, No. (%) | 944 (59.4) | 779 (51.1) | 615 (41.8) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| British white ethnicity, No. (%)c | 1457 (98.0) | 1371 (98.0) | 1298 (98.0) | .41 |

|

| ||||

| Father’s occupation, nonmanual, No. (%)d | 885 (63.0) | 789 (61.0) | 715 (59.0) | .04 |

|

| ||||

| Mother’s postnatal depression score, mean (SD)e | 5.7 (4.45) | 5.9 (4.69) | 5.9 (4.60) | .23 |

|

| ||||

| SDQ total score at age 7 y, mean (SD) | 7.0 (4.62) | 7.3 (4.76) | 7.4 (4.81) | .08 |

|

| ||||

| BMI at age 9 y, mean (SD) | 16.7 (1.91) | 17.5 (2.50) | 18.5 (3.42) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); IL-6, interleukin 6; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Cut off values for the top and bottom thirds of the distribution of IL-6 values in the total sample (cases and noncases combined) were 1.08 and 0.57 pg/mL, respectively.

One-way analysis of variance for continuous data (age, mother’s depression score, SDQ score, and BMI); χ2 test for proportions (male sex, British white ethnicity, and father’s occupation).

Data were available for 4210 participants (denominators for the bottom, middle, and top thirds were 1487, 1399, and 1324, respectively).

Data were available for 3911 participants (denominators for the bottom, middle, and top thirds were 1405,1294, and 1212, respectively).

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale total score recorded at 8 weeks post partum.

Risk of Depression and Psychosis at Age 18

At follow-up, 422 of 2447 participants (17.2%) met the case definition for CIS-R depression; 121 of these individuals (4.9%) were men. Of the 2522 individuals interviewed, PEs were reported by 101 people (4.0%); 32 were men (1.3%). Thirty-five participants (1.4%) met the case definition for psychotic disorder; 8 (0.3%) were men. Serum IL-6 levels at age 9 were significantly higher in individuals with subsequent depression or PEs compared with the rest of the cohort (Table 2).

Table 2. Serum IL-6 and CRP Values at Age 9 Years Between Psychiatric Cases and the Rest of the Risk Set at Age 18 Years.

| Depression at 18 y |

Psychotic Experience at 18 y |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Case | Noncase | P Valuea | Case | Noncase | P Valuea |

| Total No. of participants | 422 | 2025 | 101 | 2427 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Serum IL-6, pg/mL | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.35 (1.59) | 1.16 (1.37) | .02 | 1.56 (1.99) | 1.16 (1.35) | .05 |

|

| ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 0.87 (0.55-1.48) | 0.74 (0.46-1.29) | .001 | 0.98 (0.53-1.72) | 0.75 (0.46-1.30) | .01 |

|

| ||||||

| Serum CRP, mg/L | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.72 (2.79) | 0.55 (1.42) | .22 | 1.12 (4.35) | 0.56 (1.57) | .19 |

|

| ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 0.21 (0.12-0.50) | 0.20 (0.11-0.46) | .09 | 0.26 (0.11-0.61) | 0.20 (0.11-0.46) | .11 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; IQR, interquartile range.

An independent-sample t test was used to compare the mean values of IL-6 and CRP between cases and noncases, and an independent-sample Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the biomarker distributions (median) between cases and noncases.

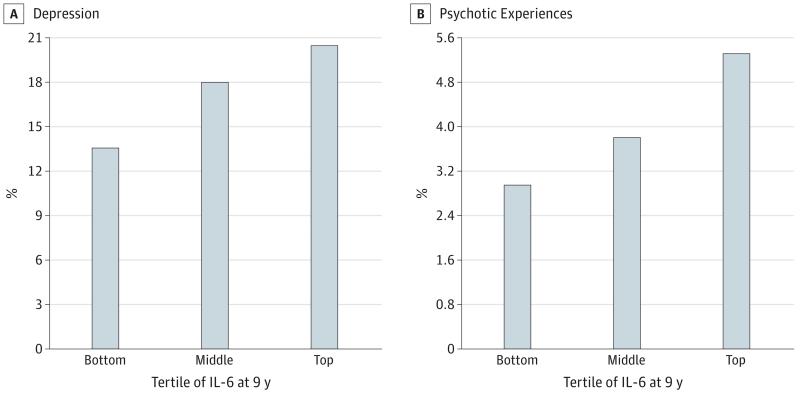

Higher baseline IL-6 levels were associated with an increased risk of depression (both CIS-R continuous and binary measures) and psychotic outcomes at follow-up. The Figure presents the proportion of individuals with depression and PE at age 18 by thirds of IL-6 at age 9.

Figure. Depression and Psychotic Experiences at Age 18 Years in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children.

Samples of depression (A) and psychotic experiences (B) were divided by tertiles of interleukin 6 (IL-6) in participants at age 9 years. Cutoff values for the top and bottom thirds of the distribution of IL-6 values in the total sample (cases and noncases combined) were 1.08 and 0.57 pg/mL, respectively.

Using the continuous measure of depression, the regression coefficient for an SD increase in the total CIS-R depression score at age 18 for each SD increase in serum IL-6 levels at age 9 was 0.07 (SE, 0.02; P = .003). After adjustment for potential confounders, this finding attenuated slightly to 0.06 (SE, 0.03; P = .02).

Using the CIS-R binary case definition, the adjusted OR for depression for participants in the top compared with the bottom third of IL-6 distribution was 1.55 (95% CI, 1.13-2.14) (Table 3). The adjusted OR for PEs was 1.81 (95% CI, 1.01-3.28) and that for psychotic disorder was 2.40 (95% CI, 0.88-6.22) (Table 4). There was no evidence of an association between psychiatric outcomes and CRP levels.

Table 3. ORs for CIS-R Depression at Age 18 Years for Serum IL-6 and CRP Levels at Age 9 Years.

| OR (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Marker | Groupa | No. | Depressed, No. (%) | Unadjusted | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d |

| IL-6 | Bottom third | 856 | 116 (13.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||||||

| Middle third | 821 | 148 (18.0) | 1.40 (1.07-1.83) | 1.39 (1.06-1.82) | 1.38 (1.03-1.86) | 1.27 (0.92-1.75) | |

|

| |||||||

| Top third | 770 | 158 (20.5) | 1.64 (1.26-2.14) | 1.61 (1.22-2.11) | 1.77 (1.33-2.36) | 1.55 (1.13-2.14) | |

|

| |||||||

| Linear trend | 2447 | 422 (17.2) | 1.27 (1.12-1.45) | 1.26 (1.10-1.44) | 1.33 (1.15-1.53) | 1.24 (1.06-1.46) | |

|

| |||||||

| CRP | Bottom third | 920 | 142 (15.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||||||

| Middle third | 791 | 140 (17.7) | 1.17 (0.91-1.52) | 1.15 (0.89-1.50) | 1.17 (0.89-1.55) | 1.02 (0.75-1.39) | |

|

| |||||||

| Top third | 742 | 141 (19.0) | 1.28 (0.99-1.66) | 1.20 (0.91-1.59) | 1.26 (0.95-1.66) | 0.98 (0.70-1.37) | |

|

| |||||||

| Linear trend | 2453 | 423 (17.2) | 1.13 (1.00-1.28) | 1.10 (0.95-1.26) | 1.12 (0.98-1.29) | 0.99 (0.83-1.17) | |

Abbreviations: CIS-R, Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; OR, odds ratio.

Cutoff values for the top and bottom thirds of the distribution of IL-6 values in the total sample (cases and noncases combined) were 1.08 and 0.57 pg/mL, respectively. Cutoff values for the top and bottom thirds of the distribution of CRP values in the total sample were 0.33 and 0.13 mg/L, respectively.

Adjusted for body mass index at age 9 years.

Adjusted for psychological and behavioral problems at age 7 years.

Adjusted for body mass index, past psychological and behavioral problems, age, sex, social class, ethnicity, and maternal postpartum depression.

Table 4. ORs for Psychotic Outcomes at Age 18 Years for Serum IL-6 and CRP Levels at Age 9 Years.

| OR (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Marker | Groupa | No. | Psychotic, No. (%) | Unadjusted | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d |

| Psychotic experiences at age 18 y | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| IL-6 | Bottom third | 887 | 27 (3.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||||||

| Middle third | 842 | 32 (3.8) | 1.25 (0.75-2.12) | 1.23 (0.73-2.09) | 1.21 (0.68-2.16) | 1.12 (0.60-2.11) | |

|

| |||||||

| Top third | 793 | 42 (5.3) | 1.78 (1.09-2.92) | 1.73 (1.04-2.88) | 1.89 (1.12-3.22) | 1.81 (1.01-3.28) | |

|

| |||||||

| Linear trend | 2522 | 101 (4.0) | 1.34 (1.04-1.71) | 1.32 (1.02-1.70) | 1.39 (1.06-1.81) | 1.36 (1.01-1.84) | |

|

| |||||||

| CRP | Bottom third | 930 | 32 (3.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||||||

| Middle third | 831 | 31 (3.7) | 1.08 (0.66-1.80) | 1.06 (0.64-1.76) | 1.06 (0.61-1.85) | 1.01 (0.55-1.83) | |

|

| |||||||

| Top third | 767 | 38 (5.0) | 1.46 (0.90-2.36) | 1.39 (0.82-2.34) | 1.62 (0.96-2.71) | 1.25 (0.67-2.34) | |

|

| |||||||

| Linear trend | 2528 | 101 (4.0) | 1.21 (0.95-1.54) | 1.18 (0.90-1.53) | 1.28 (0.98-1.66) | 1.12 (0.82-1.53) | |

|

| |||||||

| Psychotic disorder at age 18 y | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| IL-6 | Bottom third | 887 | 9 (1.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||||||

| Middle third | 842 | 8 (1.0) | 0.93 (0.36-2.43) | 0.95 (0.36-2.48) | 0.63 (0.18-2.16) | 0.53 (0.13-2.14) | |

|

| |||||||

| Top third | 793 | 18 (2.3) | 2.26 (1.01-5.07) | 2.36 (1.03-5.39) | 2.39 (0.97-5.91) | 2.40 (0.88-6.22) | |

|

| |||||||

| Linear trend | 2522 | 35 (1.4) | 1.58 (1.03-2.42) | 1.61 (1.04-2.49) | 1.69 (1.03-2.78) | 1.73 (1.00-3.03) | |

|

| |||||||

| CRP | Bottom third | 930 | 10 (1.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||||||

| Middle third | 831 | 16 (1.9) | 1.80 (0.81-4.00) | 1.77 (0.79-3.98) | 1.45 (0.57-3.70) | 1.31 (0.47-3.65) | |

|

| |||||||

| Top third | 767 | 9 (1.2) | 1.09 (0.44-2.70) | 1.06 (0.40-2.80) | 1.25 (0.46-3.36) | 0.92 (0.28-2.99) | |

|

| |||||||

| Linear trend | 2528 | 35 (1.4) | 1.05 (0.70-1.58) | 1.05 (0.67-1.63) | 1.12 (0.70-1.79) | 0.97 (0.55-1.70) | |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; OR, odds ratio.

Cutoff values for the top and bottom thirds of the distribution of IL-6 values in the total sample (cases and noncases combined) were 1.08 and 0.57 pg/mL, respectively. Cutoff values for the top and bottom thirds of the distribution of CRP values in the total sample were 0.33 and 0.13 mg/L, respectively.

Adjusted for body mass index at baseline.

Adjusted for psychological and behavioral problems at age 7 years.

Adjusted for body mass index, past psychological and behavioral problems, age, sex, social class, ethnicity, and maternal postpartum depression.

The associations between baseline IL-6 and subsequent depression and PEs were both consistent with a linear relationship. For each SD increase in IL-6, the OR for CIS-R binary depression was 1.14 (95% CI, 1.03-1.26; P = .01) and the OR for PEs was 1.24 (95% CI, 1.06-1.46; P = .006). The quadratic terms for IL-6 within these regression models were non significant (P = .15 and P = .57, respectively).

We carried out additional analyses to examine the association between IL-6 and depression. Interleukin 6 was associated with depression using 2 alternative cutoff scores for CIS-R to define cases (eTable 1 in the Supplement), as well as the alternative measure of depression, MFQ (eResults, eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Effects of Previous Psychological and Behavioral Problems on Later IL-6 and Psychiatric Outcomes

The SDQ score at age 7 was associated with IL-6 levels at age 9, and both factors were independently associated with subsequent risks for depression and, separately, PE at age 18. The ORs for these psychiatric outcomes for IL-6 after adjusting for the SDQ score were robust and remained statistically significant (Tables 3 and 4). Thus, our data suggest that the associations between IL-6 and later psychiatric outcomes are independent of the effect of early-life psychological and behavioral problems on IL-6 levels.

Effect Modification by Sex

No test results for the interaction between IL-6 and sex in the logistic regression models of IL-6 and CIS-R depression, PEs, and psychotic disorder approached statistical significance (P = .94, P = .51, and P = .56, respectively). These findings indicate that there were no sex differences in the associations between IL-6 and subsequent psychiatric outcomes.

Results After Imputation of Missing Outcome Data

The pattern of all results remained remarkably similar. Interleukin 6 was associated with depression (CIS-R and MFQ, both continuous and binary measures) and PE (eResults and eTables 3, 4, and 5 in the Supplement). After imputation and adjustment for confounders, the ORs for CIS-R binary definition of depression and the ORs for PEs fell short of conventional statistical significance.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate a longitudinal dose-response association between childhood IL-6 levels and future risk for depression in young adulthood. The association persisted after adjusting for several potential confounders including sex, BMI, social class, past psychological and behavioral problems, and maternal depression. Childhood IL-6 levels were associated with subsequent PEs, again in a dose-dependent manner. Interleukin 6 was also associated with the stricter phenotype of psychotic disorder at age 18.

Cross-sectional studies17,24 suggest that increased IL-6 and CRP levels occur in current depression and psychosis. However, there have been few longitudinal studies of inflammatory markers before depression, and these have yielded inconsistent results. One study26 based on hospital admission data found no evidence that CRP levels predicted later depression. Few patients with depression require hospitalization, so hospital register studies are prone to ascertainment bias. A large study27 of London civil servants reported that IL-6 and CRP levels were associated with later cognitive symptoms of depression in men. One study28 involving perimenopausal women reported an association between CRP and later depression. Our findings in a general population birth cohort demonstrate associations between IL-6 and later depression and PEs independent from the effect of previous psychological problems on IL-6.

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study of any inflammatory marker in childhood and subsequent psychotic disorder. We included the restricted category of psychotic disorder to assess whether the association became stronger when this category was applied. The operational definition for psychotic disorder, as described in the Methods section, has been used previously.31 The OR for psychotic disorder for higher IL-6 levels was slightly larger than that for PEs (Table 4). However, only 19 cases with complete data on confounders were included in this analysis; the 95% CI for the OR included unity, but the pattern of the results remained the same. We included participants with PEs or psychotic disorders who were not depressed in the comparison group in the analysis of depression and vice versa. This process is likely to have resulted in an underestimation of the true association between IL-6 and later psychiatric outcomes.

One limitation of the present study is attrition. Nearly half of the individuals with inflammatory marker data at baseline did not attend psychiatric follow-up sessions. However, the mean and median values of IL-6 were similar between the groups who did and did not attend assessments for depression and PEs. Compared with participants who attended the clinic at age 18, those who did not attend had more psychological problems at age 7 and lower socioeconomic status, and their mothers had higher postpartum depression scores. These factors were associated with an increased risk of psychiatric outcomes at age 18. Thus, it is likely that any bias from sample attrition has led to an underestimation of the true association between IL-6 and later psychiatric morbidity. Furthermore, we carried out multiple imputations to examine the effect of missing data. The pattern of all results remained remarkably similar after imputation of missing outcome data, increasing our confidence in the robustness of these results.

Subsequent blood samples from childhood were not analyzed to examine long-term, within-individual consistency of IL-6 levels. However, one study36 of healthy volunteers found no significant changes in IL-6 levels during a 3-year period. We acknowledge that nonfasting blood samples may be open to possible diurnal variation in the levels of some cytokines.37 However, the use of nonfasting samples would increase measurement error that is likely to be random in relationship to the outcome. Measurement error might also explain why an association with CRP was not observed because IL-6 is primarily responsible for CRP induction.38

A clearer understanding of the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of depression and psychosis may lead to new treatments. Randomized clinical trials of celecoxib (a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor) as an adjunct to standard treatment have shown encouraging results in depression39 and schizophrenia.40 However, the use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors may be problematic because they can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.41 Minocycline, a centrally acting tetracylic anti-inflammatory agent, has been reported42 to improve negative symptoms in schizophrenia. These findings need replication in larger samples. Preclinical research to identify specific inflammatory pathways contributing to neuropsychiatric symptoms may help to devise more targeted interventions.

Associations between inflammation and both depression and psychosis are consistent with the well-known clinical and etiologic (including genetic) overlap between these disorders.43,44 Inflammation might explain the high comorbidity between these neuropsychiatric disorders and chronic physical illness, such as heart disease12 and diabetes mellitus.13 Longitudinal associations between inflammatory markers and heart disease,7-9,11 diabetes,10 depression, and psychosis could all be linked with early-life factors influencing inflammatory regulation, such as impaired fetal development or childhood adversity. This view is consistent with Barker’s45 common-cause hypothesis, which postulates that alterations in physiologic systems from early-life adversity can increase the risk for several chronic diseases in adulthood. Low birth weight, a marker of suboptimal fetal development, is associated with increased circulating inflammatory markers46 and risks of heart disease, diabetes,45 depression,47 and schizophrenia in adults.47 Thus, inflammation might be a common cause for many chronic adult diseases.

Conclusions

Our study provides evidence for a longitudinal association between a circulating inflammatory marker in childhood and future risks for depression and psychosis. Inflammatory pathways may provide important new prevention and intervention targets for major mental illnesses while also undermining the unhelpfully persistent Cartesian division between the mind and body.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by doctoral clinical research training grant 094790/Z/10/Z from the Wellcome Trust PhD Programme for Clinicians, Cambridge Institute of Medical Research, University of Cambridge (Dr Khandaker), Wellcome Trust grants 095844/Z/11/Z and 088869/Z/09/Z and National Institute for Health Research grant RP-PG-0606-1335 (Dr Jones), and Wellcome Trust grant 084268/Z/07/Z for studying depression and UK Medical Research Council grant G0701503 for studying psychosis in ALSPAC. Medical Research Council grant 74882, Wellcome Trust grant 092731, and the University of Bristol provide core support for the ALSPAC birth cohort.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding bodies had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We are grateful to all of the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting the families, and the whole ALSPAC team including interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, statisticians, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses.

Footnotes

Supplemental content at jamapsychiatry.com

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):448–457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1201534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. National Comorbidity Survey Replication The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1022–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danesh J, Kaptoge S, Mann AG, et al. Long-term interleukin-6 levels and subsequent risk of coronary heart disease: two new prospective studies and a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050078. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-Reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1387–1397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Pennells L, et al. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and cardiovascular disease prediction. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1310–1320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers, hormone replacement therapy, and incident coronary heart disease: prospective analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study. JAMA. 2002;288(8):980–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.8.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anda R, Williamson D, Jones D, et al. Depressed affect, hopelessness, and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of US adults. Epidemiology. 1993;4(4):285–294. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushe C, Holt R. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;47:S67–S71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.47.s67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belmaker RH, Agam G. Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):55–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlton PL, Manowitz P. Dopamine and schizophrenia: an analysis of the theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8(1):137–151. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, et al. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(5):445–452. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Lewis G, Jones PB. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):239–257. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benros ME, Nielsen PR, Nordentoft M, Eaton WW, Dalton SO, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for schizophrenia: a 30-year population-based register study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1303–1310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Dalman C, Lewis G, Jones PB. Childhood infection and adult schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1-3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):812–820. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):171–186. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner RM, Dalman C, Wicks S, Lee BK, Karlsson H. Neonatal levels of acute phase proteins and later risk of non-affective psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e228. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.5. doi:10.1038/tp.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wium-Andersen MK, Ørsted DD, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated C-reactive protein levels, psychological distress, and depression in 73 131 individuals. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):176–184. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gimeno D, Kivimäki M, Brunner EJ, et al. Associations of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with cognitive symptoms of depression: 12-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med. 2009;39(3):413–423. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews KA, Schott LL, Bromberger JT, Cyranowski JM, Everson-Rose SA, Sowers M. Are there bi-directional associations between depressive symptoms and C-reactive protein in mid-life women? Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22(2):465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zammit S, Kounali D, Cannon M, et al. Psychotic experiences and psychotic disorders at age 18 in relation to psychotic experiences at age 12 in a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):742–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, Version 2.0. Psychiatric Publishers International/American Psychiatric Press Inc; Geneva, Switzerland: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3-4):276–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knudsen LS, Christensen IJ, Lottenburger T, et al. Pre-analytical and biological variability in circulating interleukin 6 in healthy subjects and patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Biomarkers. 2008;13(1):59–78. doi: 10.1080/13547500701615017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Jager W, Bourcier K, Rijkers GT, Prakken BJ, Seyfert-Margolis V. Prerequisites for cytokine measurements in clinical trials with multiplex immunoassays. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-52. doi:10.1186/1471-2172-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janeway CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th ed. Garland Science; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Müller N, Schwarz MJ, Dehning S, et al. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib has therapeutic effects in major depression: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, add-on pilot study to reboxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(7):680–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller N, Riedel M, Scheppach C, et al. Beneficial antipsychotic effects of celecoxib add-on therapy compared to risperidone alone in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):1029–1034. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286(8):954–959. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaudhry IB, Hallak J, Husain N, et al. Minocycline benefits negative symptoms in early schizophrenia: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial in patients on standard treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(9):1185–1193. doi: 10.1177/0269881112444941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. ed 4 American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green EK, Grozeva D, Jones I, et al. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium The bipolar disorder risk allele at CACNA1C also confers risk of recurrent major depression and of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(10):1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barker DJP, Robinson RJ. Fetal and Infant Origins of Adult Disease. 1st ed. BMJ Books; London, England: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tzoulaki I, Jarvelin MR, Hartikainen AL, et al. Size at birth, weight gain over the life course, and low-grade inflammation in young adulthood: northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(8):1049–1056. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abel KM, Wicks S, Susser ES, et al. Birth weight, schizophrenia, and adult mental disorder: is risk confined to the smallest babies? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(9):923–930. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.