Abstract

A small population of neuroendocrine cells in the rostral hypothalamus and basal forebrain is the key regulator of vertebrate reproduction. They secrete gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH-1), communicate with many areas of the brain and integrate multiple inputs to control gonad maturation, puberty and sexual behavior. In humans, disruption of the GnRH-1 system leads to hypogonadotropic gonadism and Kallmann syndrome. Unlike other neurons in the central nervous system, GnRH-1 neurons arise in the periphery, however their embryonic origin is controversial, and the molecular mechanisms that control their initial specification are not clear. Here, we provide evidence that in chick GnRH-1 neurons originate in the olfactory placode, where they are specified shortly after olfactory sensory neurons. FGF signaling is required and sufficient to induce GnRH-1 neurons, while retinoic acid represses their formation. Both pathways regulate and antagonize each other and our results suggest that the timing of signaling is critical for normal GnRH-1 neuron formation. While Kallmann’s syndrome has generally been attributed to a failure of GnRH-1 neuron migration due to impaired FGF signaling, our findings suggest that in at least some Kallmann patients these neurons may never be specified. In addition, this study highlights the intimate embryonic relationship between GnRH-1 neurons and their targets and modulators in the adult.

Keywords: adenohypophysis, anterior pituitary, chick, neural crest cells, neurogenesis, neuroendocrine cells, olfactory placode

Introduction

The olfactory system is not only critical for odor detection, but also for controlling reproductive behavior (Dulac and Torello, 2003; Meredith, 1998). This function is mediated by hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH-1) neurons (Gore, 2002; Jennes and Conn, 2002; Silverman et al., 1994; Sisk and Foster, 2004), which integrate multiple inputs and modulate brain functions essential for odor-processing, reproductive physiology and gender-specific sexual behavior (Boehm et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2005). Projecting to the median eminence, they secrete GnRH-1 into the portal system of the pituitary controlling gonadotropin release. Failure of this system results in hypogonadism as in the hypogonadal mouse or in human Kallmann syndrome (KS), where GnRH-1 neurons do not reach their final position (Cariboni and Maggi, 2006; Livne et al., 1992a; Livne et al., 1992b; Mason et al., 1986; Wray, 2002).

Unlike most central nervous system neurons, GnRH-1 neurons arise peripherally, migrate along the olfactory/vomeronasal nerve into the telencephalon and turn caudally into the hypothalamus (Abraham et al., 2009; Mulrenin et al., 1999; Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Whitlock et al., 2003; Wray et al., 1989a). However, their precise developmental origin remains controversial: the olfactory placode, the anterior pituitary, neural crest cells and the respiratory epithelium have all been reported to generate GnRH-1 neurons (Daikoku-Ishido et al., 1990; Daikoku and Koide, 1998; Dellovade et al., 1998; el Amraoui and Dubois, 1993; Forni et al., 2011; Metz and Wray, 2010; Mulrenin et al., 1999; Murakami and Arai, 1994a; Palevitch et al., 2007; Suter et al., 2000; Whitlock, 2004; Whitlock et al., 2006; Whitlock et al., 2003). Either a placode or neural crest cell origin for GnRH-1 neurons is plausible from a developmental perspective: both tissues generate a variety of migratory progeny including neuroendocrine cells (Baker and Bronner-Fraser, 2001; Le Douarin and Kalcheim, 1999; Schlosser, 2006; Streit, 2007).

Irrespective of their origin, the transcription factors and the signals that impart GnRH-1 identity to neuronal precursors are currently unknown. In mouse, GnRH-1 neurogenesis appears to follow a pathway distinct from most other neurons that is independent of canonical bHLH neuronal determination genes (Kramer and Wray, 2000). While several factors are known to regulate GnRH-1 transcription (Givens et al., 2005; Kelley et al., 2000; Lawson and Mellon, 1998; Lawson et al., 1996; Rave-Harel et al., 2005), their role in GnRH-1 neuron specification has not been investigated in detail. Mutation in fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) and its receptor FGFR1 are associated with human KS (Cariboni and Maggi, 2006; Dode et al., 2003); (Falardeau et al., 2008). However, FGFs act repeatedly during forebrain, olfactory and anterior pituitary development controlling the formation of both placodes, olfactory neuroblast proliferation, cell fate specification in the anterior pituitary and GnRH-1 neuron migration (Bailey et al., 2006; Chung et al., 2008; Falardeau et al., 2008; Gill et al., 2004; Guner et al., 2008; Herzog et al., 2004; Kawauchi et al., 2005; Tsai et al., 2005). It is therefore difficult to assess the precise role of FGF signaling in GnRH-1 neuron development. A second signaling pathway, retinoic acid (RA) acts through two distinct enhancers to repress or induce GnRH-1 (Cho et al., 2001a; Cho et al., 2001b), but its function in GnRH-1 neuron formation is unknown. Thus, despite their importance as integrators of reproduction, the molecular mechanisms that specify GnRH-1 neurons remain unclear.

Here, we identify the olfactory placode as the embryonic source of GnRH-1 neurons in the chick. Following olfactory sensory neuron specification, FGF signaling induces GnRH-1 precursors in a brief window of competence, while RA represses them. Both pathways act mutually antagonistic to determine the time and location of GnRH-1 neuron formation.

Materials and Methods

Embryos and bead grafts

Fertile hens’ eggs (Stewart Farm, UK) and GFP transgenic hens’ eggs (Roslin Institute; (McGrew et al., 2008) were incubated at 38°C in a humidified incubator to the desired stage (HH, (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951). Ag1X2 beads were coated with 25 μM all-trans retinoic acid or 100 μM SU5402 in DMSO for 15-30 min at room temperature or treated with DMSO (controls), washed in Tyrode’s saline and grafted next to the medial edge of the olfactory placode of HH16 or HH18 chick embryos. Embryos were grown for 12-16 hours before being fixed and processed for in situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

For in situ hybridization on paraffin sections, embryos and explants were fixed in modified Carnoy’s solution (60% ethanol, 11.1% formaldehyde, 10% acetic acid), dehydrated into 100% ethanol, embedded in paraplast and sectioned at 8-12 μm. In situ hybridization was carried out as previously described (Xu et al., 2008) using digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled antisense RNA probes for Eya2 (Mishima and Tomarev, 1998), RALDH3 (Blentic et al., 2003), GnRH-1 (a gift from Dr. Ian Dunn), FGF8 (a gift from J.C. Izpisúa-Belmonte), Ebf1 (ChEST910a18) and NeuroD (Bell et al., 2008).

Immunohistochemistry was performed on cryosections (Bhattacharyya et al., 2004) using polyclonal antibodies against GnRH-1 (Abcam, 1:100), phospho-histone H3 (Upstate, 1:100) and GFP (FITC-conjugated, Abcam, 1:250 and Invitrogen, 1:2000), monoclonal antibodies against the neuronal markers HuC/D (Invitrogen, 1:100) and neuronal III tubulin (TuJ1, Covance; 1:250) and appropriate Alexafluor 488- and 594-coupled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen; 1:500-1:1000). For Tuj1, biotinylated IgG2a-specific secondary antibody was used in conjunction with Alexa 350-conjugated NeutrAvidin (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained by 10μg/ml DAPI (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M and an Axiocam camera or a laser scanning LEICA TCS SP5 confocal microscope.

Lineage labeling

Small groups of cells in the presumptive olfactory and anterior pituitary placodes of HH8 chick embryos were labeled with the fluorescent lipophilic dye CM-DiI (0.5% in absolute alcohol, diluted 1:10 in 0.3 M sucrose) using microcapillaries (Streit, 2002). The position of each injection was photographed; eggs were sealed and incubated until embryonic day E5/6. Labeled embryos were fixed overnight in modified Carnoy’s solution, paraffin-embedded, sectioned and photographed before labeling with GnRH-1 anti-sense probes. To label neural crest cells migrating into the frontonasal mass, midbrain-level neural folds from GFP transgenic chick embryos (Roslin Institute; (McGrew et al., 2008) at HH8 were grafted into the same position of a wild type host. Presumptive olfactory placodes (Bhattacharyya et al., 2004) were grafted from GFP transgenic chick embryos to wild type hosts at HH8. Embryos were further incubated until embryonic day E6.5 (HH30) before being processed for in situ hybridization with GnRH-1 antisense probes and immunohistochemistry with GFP, GnRH-1 or Tuj1 antibodies.

Explant cultures

Embryos from HH15-20 were harvested in Tyrode’s saline and olfactory placodes dissected from underlying mesendoderm using 0.05% dispase. Explants were kept on ice before being cultured in collagen (Streit et al., 1997) prepared in medium 199 containing N2 supplement (Invitrogen). Explants were cultured for 60–72 hr in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml FGF8 (R&D), 5 mM SU5402 ((Bailey et al., 2006) ; Calbiochem), 30 μM Citral ((Song et al., 2004); Sigma) or 10−6 M all-trans RA ((Song et al., 2004); Sigma) before being processed for immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization on sections. To quantify the number of GnRH-1+ cells in each explant, z images of each section were taken and a z-stack was reconstructed with ImageJ software available from http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ (Abramoff et al., 2004). The 3D object counter was used to count positive cells. An unpaired Student’s t- test was performed to determine the significance between control and treated conditions.

Results

The olfactory placode gives rise to GnRH-1 neurons

Although GnRH-1 expressing cells are first detected in the olfactory placode (Mulrenin et al., 1999; Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Wray, 2002; Wray et al., 1989a) various origins for GnRH-1 neurons have been proposed in amniotes and teleosts including the olfactory placode, the anterior pituitary and neural crest cells (Daikoku-Ishido et al., 1990; Daikoku and Koide, 1998; Dellovade et al., 1998; el Amraoui and Dubois, 1993; Forni et al., 2011; Metz and Wray, 2010; Mulrenin et al., 1999; Murakami and Arai, 1994a; Suter et al., 2000; Whitlock, 2004; Whitlock et al., 2006; Whitlock et al., 2003). We took advantage of the chick where existing, accurate fate maps (Bhattacharyya et al., 2004; Couly and Le Douarin, 1988; Couly and Le Douarin, 1985; Le Douarin, 1986; Le Douarin and Kalcheim, 1999; Streit, 2002; Xu et al., 2008) allow temporally and spatially controlled lineage labeling and transplantation experiments.

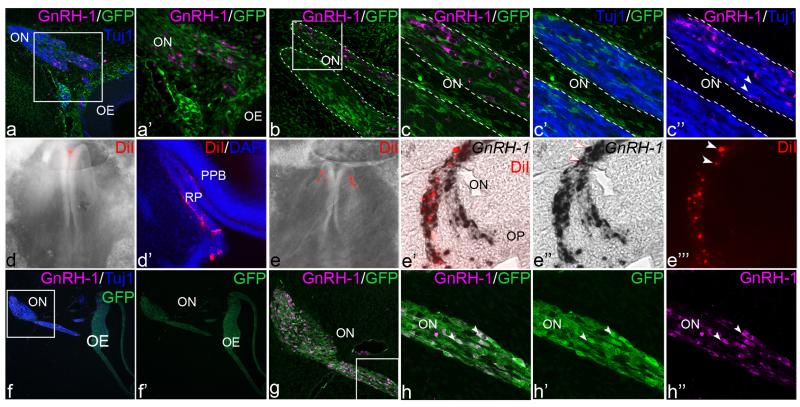

To investigate whether cranial neural crest cells contribute to GnRH-1 neurons, the neural folds (future neural crest) of GFP transgenic chick embryos were grafted into the same position of a wild type host at HH8 (n=7; Fig. 1a-c”). At HH30, when GnRH-1 neuron production is prominent, GFP+ neural crest cells fill the frontonasal mass and surround the olfactory nerve, but are never found in the olfactory epithelium (Fig. 1a-c”; see also (Barraud et al., 2010). GnRH-1+ cells are located along the nerve but not in the olfactory epithelium as observed earlier (HH25), however they never express GFP (Fig. 1a-c, c”; in 3 specimen 0/595 GnRH-1+ neurons are GFP+; 0% +/− 0). Likewise, GFP+ neural crest-derived cells never express the neuronal markers Tuj1 (Fig. 1a-a’, c’) or Hu (not shown; see also: Barraud et al., 2010). These findings show that chick neural crest cells do not contribute to the olfactory epithelium, and do not generate any neurons within the olfactory system including GnRH-1 neurons.

Fig. 1. GnRH-1 neurons arise from the olfactory placode in chick.

a-c”: cranial neural crest cell grafts from transgenic GFP chick embryos (green) into wild type hosts generate the frontonasal mass and surround the olfactory nerve (ON), but do not express GnRH-1 (magenta) or Tuj1 (blue) and do not contribute to the olfactory epithelium (OE). a. section through the olfactory region. a’ represents a higher magnification of the boxed area in a; GnRH-1 neurons do not express GFP. b. close-up view of the olfactory nerve (outlined in white). c-c” are higher magnifications of the boxed area in b. GFP+ cells are do not express GnRH-1 or Tuj1; in contrast some Tuj1+ neurons are also GnRH-1+ (arrow heads in c”). de”’: the presumptive anterior pituitary placode (d, d’) or olfactory placode (e-e”’) was labeled with CM-DiI in HH8 chick embryos (d, e; red). Labeled anterior pituitary descendants (red) are only found in Rathke’s pouch (RP; d’) adjacent to the posterior pituitary bud (PPB), while olfactory placode descendants (red) are present in the olfactory placode (OP) and along the olfactory nerve (ON; e’-e”’); DiI labeled cells express GnRH-1 (arrow heads in e”, e”’). f-h”: olfactory placode grafts from transgenic GFP chick embryos (green) to wild type hosts. f: GFP+ cells form the olfactory epithelium (OE), the Tuj1+ olfactory nerve (ON; blue) and GnRH-1+ (magenta) cells migrating along the olfactory nerve. f’: GFP channel of the image shown in f. g: represents a higher magnification of the boxed area in f showing GFP/GnRH-1 double positive cells. h-h” a higher magnification of the boxed area in f showing cells expressing GFP and GnRH-1 (white arrow heads).

To assess the putative placodal origin of GnRH-1 neurons, we used focal injections of CMDiI in stage HH8 embryos to label either anterior pituitary or olfactory placode precursors (Couly and Le Douarin, 1985, 1987). At stage HH25/26, descendants of DiI-labeled anterior pituitary precursors specifically localize to Rathke’s pouch, as expected (Fig. 1d’; n=16), but are never present near the olfactory epithelium or along the olfactory nerve, where GnRH-1 neurons are found. Thus, the anterior pituitary placode does not produce GnRH-1 neurons. In contrast, at HH26 descendants of DiI-labeled olfactory placode precursors populate the dorsal part of the olfactory pit, are found along the olfactory nerve and express GnRH-1 (Fig. 1e-e”’; n=18). To confirm these results using a different approach we grafted the future olfactory placode from HH8 GFP transgenic chick embryos into the same position of stage-matched hosts (n=4; Fig. 1f-h”). At HH30, the olfactory placode and nerve are GFP+ as expected, as are GnRH-1+ neurons (Fig. 1f-h”; in 4 specimen 333/417 GnRH-1+ cells are also GFP+; 79.8% +/− 19.5). In summary, our results show that in the chick GnRH-1 neurons are derived from the olfactory placode.

GnRH-1 neurons are specified prior to their emergence from the olfactory placode

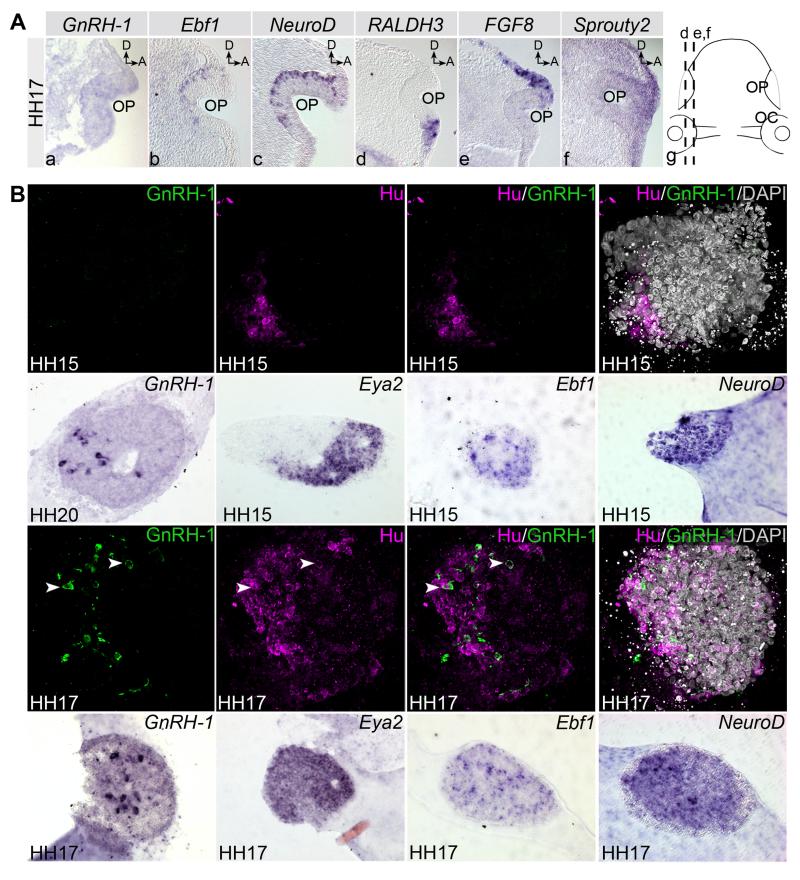

In the olfactory placode, sensory neurogenesis is well underway at HH17, as evident from the expression of Ebf1 and NeuroD (Fig. 2Ab, c), however GnRH-1 transcripts are absent (Fig. 2Aa) and only detected from HH19 onwards (Mulrenin et al., 1999; Norgren and Lehman, 1991). At later stages (HH25/26), GnRH-1 neurons are present in the dorsal-medial aspect of the olfactory placode and migrate along the olfactory nerve (Fig. 1e’, e”). To investigate when the olfactory placode is able to generate GnRH-1 neurons autonomously (i.e. the time of GnRH-1 neuron specification), we established an explant assay using serum-free conditions. To assess whether these conditions are suitable for GnRH-1 neuron culture, we explanted olfactory placodes from HH20, when GnRH-1 transcripts are already expressed. As expected, these explants are GnRH-1 positive after 60 hours’ culture (n=4, Fig. 2B). In contrast, olfactory explants from HH15 fail to generate GnRH-1+ cells even after prolonged culture (n=6; Fig. 2B), but do express the neuronal markers Hu, Ebf1 and NeuroD (n=6, n=10 and n= 5, respectively; Fig. 2B). Thus, olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) are already specified at HH15 (see also: (Maier et al., 2010), while GnRH-1 neurons are not. At stage HH16, olfactory explants produce very few GnRH-1+ cells (n=26) and their number increases in HH17 explants after 2.5 days’ culture (2.1±0.8% of all cells in each explant; Fig. 3B). Over the entire culture period, explants continue to express the placode marker Eya2 and the neuronal markers Ebf1, NeuroD and Hu (Fig. 2B). These results show that the olfactory placode initiates the formation of sensory neurons prior to the production of neuroendocrine GnRH-1 cells. Remarkably, although GnRH-1 is only detected at HH19 in vivo, GnRH-1 precursors are already specified at HH16/17 indicating that at this stage the olfactory placode contains all factors required for their formation.

Fig. 2. Gene expression patterns in the olfactory placode and specification of GnRH-1 neurons.

A. Gene expression in parasagittal sections of the chick olfactory area at HH17 (a-g). GnRH-1 (a) is not yet expressed in the olfactory placode (OP), while neuronal markers Ebf1 (b) and NeuroD (c) are present in a salt and pepper pattern. RALDH3 is expressed at the ventro-lateral rim of the placode (d), while FGF8 (e) and Sprouty2 (f) are present dorsomedial. g: diagram of a ventral view of a chick HH17 head; lines indicate the position of sections in d-f. Orientation is dorsal (D) to the top; anterior (A) to the right. B. GnRH-1 neuron specification. Olfactory placodes from different stages (indicated in the lower left corner of each panel) were cultured in vitro and assayed for the expression of molecular markers. Olfactory placodes from HH15 do not express GnRH-1 (top row; green), but produce Hu+ neurons (magneta); nuclei are visualized using DAPI. Placodes from HH20 express GnRH-1 (2nd row). HH15 explants are also positive for the placode marker Eya2 (2nd row) and for neuronal progenitor markers (NeuroD, Ebf1, 2nd row). Immunocytochemistry shows that, in addition to Hu, explants isolated from HH17 also express GnRH-1 (3rd row): GnRH-1 neurons are specified. DAPI labels nuclei. Likewise, HH17 explants express GnRH-1 transcripts as well as Eya2, NeuroD and Ebf1 (row 4). Markers are indicated in the top right of each panel. Arrow heads in the 3rd row indicate GnRH-1/Hu+ cells.

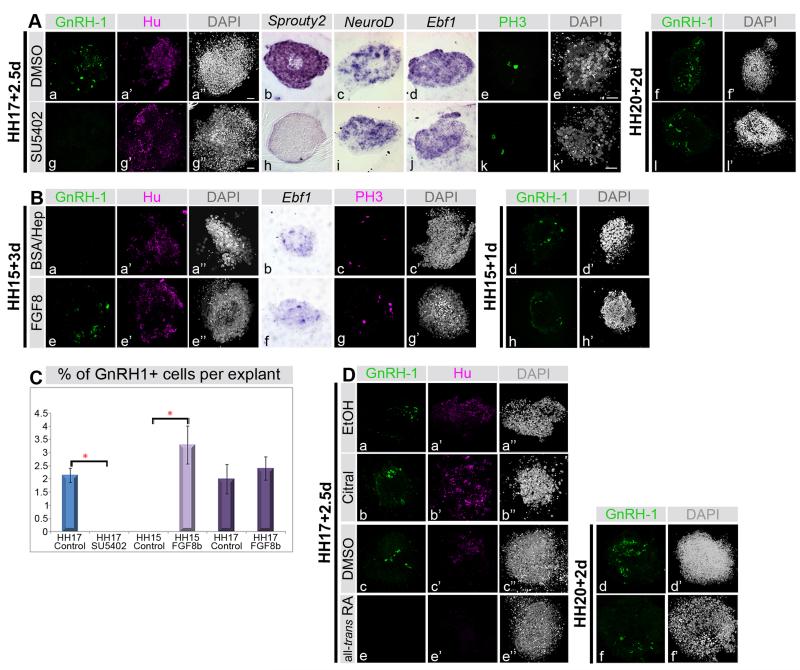

Fig. 3. FGF signaling specifies GnRH-1 neurons during a narrow time window, while RA inhibits their formation.

A. Olfactory placode explants from HH17 generate GnRH-1 and Hu positive neurons (a-a”), express the FGF target Sprouty2 (b) and the neuronal markers NeuroD and Ebf1 (c, d) after 2.5 days in culture. When FGF signaling is inhibited (g-k’) by SU5402, GnRH-1 (g) and Sprouty2 (h) expression is lost, while all Hu (g’), NeuroD (i) and Ebf1 (j) are maintained. Proliferation as indicated by PH3 staining (e, k) is unaffected. When explants from HH20 are cultured for 2 days in vitro they express GnRH-1 (f; green) even when FGF signaling is inhibited (l). DAPI (a”, e’, g”, f’, k’, l’) labels nuclei.

B. After 3 days in culture, HH15 olfactory placode explants are GnRH-1 negative (a), but express Hu (a’) and Ebf1 (b). FGF8 induces GnRH-1 expression (e), while there is no change in Hu (e’) or Ebf1 (f) expression, or in proliferation as revealed by PH3 staining (c, f).

GnRH-1 expression is induced when olfactory explants are exposed to FGF8 for 3 days continuously (f) or when exposed to FGF8 for one day, followed by 2 days in its absence (l). This suggests that short exposure to FGF8 is sufficient to initiate GnRH-1 production. DAPI (a”, c’, d’, e”, g’, h’) labels nuclei.

C. Quantification of GnRH-1+ under different conditions; bar diagram shows average % of GnRH-1+ cells per explant. There is a significant difference between controls and Su5402 treated HH17 explants and between control and FGF8-treated HH15 explants (*). FGF8 does not increase the numbers of GnRH-1 neurons significantly at HH17.

D. RA inhibits GnRH-1 neuron formation. Inhibition of RA signaling in HH17 olfactory placode explants using Citral does not affect GnRH-1 or Hu expression: there is no difference in control (a-a”) and Citral treated explants (b-b”). In contrast, all-trans RA inhibits the formation of GnRH-1+ and Hu+ cells; controls (c-c”) express both markers, but they are lost in the presence of RA (e-e”). After HH20, GnRH-1 neurons explants are not sensitive to all-trans RA treatment: both control (d, d’) and RA-treated explants (f, f’) express GnRH-1 (d, f).

FGF signaling acts in a brief time window to specify GnRH-1 neurons in the olfactory placode

While olfactory sensory progenitors depend on FGF signaling and are negatively regulated by TGFβs (Beites et al., 2005; Calof et al., 2002; Kawauchi et al., 2005), the signals that initiate the formation of GnRH-1 neurons are currently unknown. At the time of GnRH-1 neuron specification (i.e., HH16/17), FGF8 and its target Sprouty2 are expressed at the dorsal-medial edge of the olfactory placode, close to where GnRH-1 neurons later delaminate from the placode (Fig. 2Ae, f; Fig. 4A). To test whether FGF signaling is required for their specification, olfactory placode explants from HH17 embryos, which consistently generate GnRH-1 neurons, were cultured in the presence or absence of the FGF receptor inhibitor SU5402. As expected, inhibition of the FGF pathway leads to a loss of Sprouty2 expression (Fig. 3Ab; h). While control explants generate GnRH-1 neurons (DMSO-treated, n=23; Fig. 3Aa, a”), inhibition of FGF signaling completely prevents their formation (n=23; Fig. 3Ag, g” and Fig. 3C). In contrast, the neuronal markers Hu (control: n=8; SU5402: n=8; Fig. 3Aa’, a”, g’, g”), Neuro D (control: n=2; SU5402: n=3; Fig. 3Ac, i) and Ebf1 (control: n=6; SU5402: n=10; Fig. 3Ad, j) are not affected. Likewise, there is no significant difference in proliferation between control and experimental explants as assayed by phospho-histone3 (PH3) staining (Fig. 3Ae, e’, k, k’; control: n=5, 1.3±0.6% pH3+ cells; SU5402: n=6, 1.5±0.7% pH3+ cells) and no difference in cell death has been reported recently under similar conditions (Maier et al., 2010).

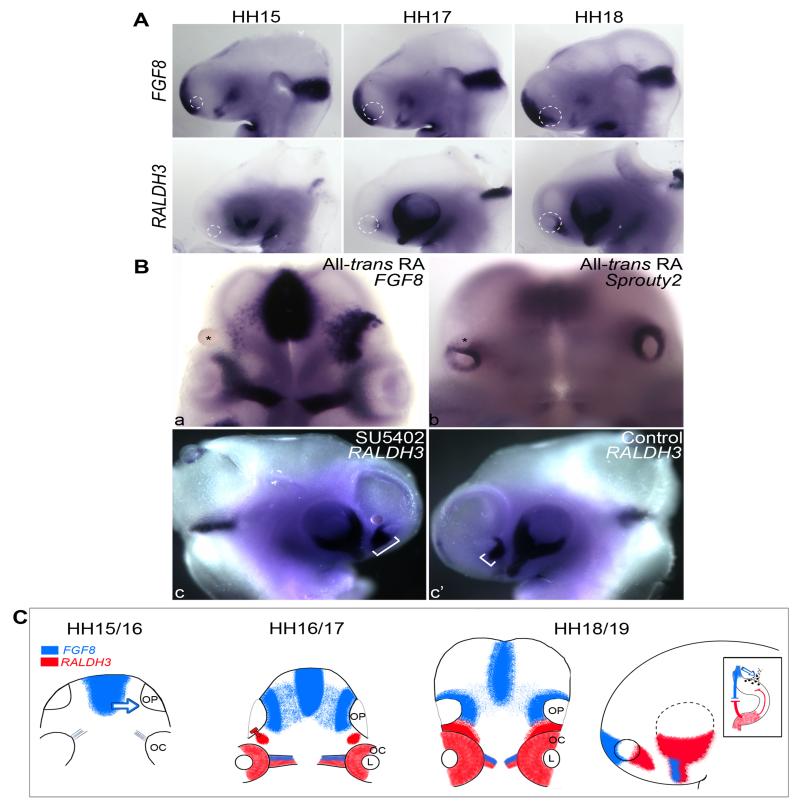

Fig. 4. Cross-regulation of FGF and RA signaling at early olfactory placode stages.

A. Complementary expression of FGF8 and RALDH3 surrounding the olfactory placode. Top row: FGF8 is expressed in the ectoderm medial to the olfactory placode (HH15) and at its medial edge from HH17 onwards. RALDH3 is absent from the olfactory region at HH15 and begins to be expressed ventro-laterally at HH17. By HH18 both genes are expressed in a complementary pattern (see also: lateral view in C.) Dotted lines outline the olfactory placode. B. All-trans RA-coated beads were transplanted next to the dorsal-anterior olfactory placode at HH15. a: FGF8 expression medial to the olfactory placode is inhibited, as is Sprouty-2 (b); * indicates position of bead. c, c’: when FGF signaling is inhibited by SU5402-coated beads grafted next to the dorsal-anterior olfactory placode at HH15, the expression of RALDH3 (brackets) is expanded (c) as compared to the contralateral side (c’). C. Model for FGF8 and RA function in GnRH-1 specification. At HH15/16 a medially localized source of FGF8 induces GnRH-1 neurons in the olfactory placode (blue, blue arrow); RALDH3 begins to be expressed at HH17 (red), counteracts FGF signaling and represses GnRH-1 neuron specification in the ventro-lateral placode. At HH18/19 FGF8 and RALDH3 abut; side view showing the same orientation as in A. Inset: diagram of a section through the olfactory region (dorsal to the top); antagonistic FGF and RA signaling position GnRH-1 neurons in the dorso-medial placode. L: lens; OP: olfactory placode; OC: optic cup.

The above results show that FGF signaling is required for initial specification of GnRH-1 neurons at HH16/17. However, it takes 2-3 days until the first GnRH-1 positive neurons emerge in vivo and in vitro. To assess whether GnRH-1 neurons depend on FGF signaling after specification, we cultured HH20 olfactory placodes in the presence or absence of SU5402. In both conditions, GnRH-1 neurons are produced (DMSO controls: n=10; SU5402: n=8; Fig. 3f, f’, l, l’). These results show that FGF signaling is required for the early phase of GnRH-1 neuron production, but not for their maintenance. Thus, both GnRH-1 and OSNs are independent of sustained FGF signaling once they are specified.

We next tested whether FGF8 is sufficient to induce GnRH-1 neurons prior to their specification (i.e. before HH16). HH15 olfactory placode explants normally do not generate any GnRH-1+ cells (n=11), however they do so in the presence of FGF8 (Fig. 3Ba, a”, e, e’, C; n=15; 3.3±2.3% of all cells in each explant), comparable to the numbers observed in explants from HH17 embryos. In contrast, FGF8 does not affect the number of Hu+ neurons (n=8; Fig. 3Ba’, a”, e’, e”) or the expression of Ebf1 (Fig. 3Bb, f; control: n=2; FGF8: n=3) and proliferation does not change (Fig. 3Bc, c’, g, g’; control: n=4, 3.3±1.4% pH3+ cells; FGF8: n=4, 2.9±1.7% pH3+ cells). After GnRH-1 neurons are specified, FGF8 treatment does not induce more cells to adopt a GnRH-1 fate: even in the presence of FGF8 the number of GnRH-1 neurons per HH17 explant does not increase (Fig. 3C; controls: n=6, 2±1.4% GnRH-1+ cells/explant; FGF8 treated: n=11, 2.4±1.5% GnRH-1+ cells/explant). These results suggest that FGF signaling only acts during a limited time period to induce GnRH-1 neuron precursors. To investigate this further, we cultured HH15 olfactory placode explants in the presence of FGF8 for 24 hours followed by another 36-48 hours’ culture without FGF8. Even when only exposed to FGF for a short time, explants generate GnRH-1 neurons (n=7; Fig.3 Bd, d’, h, h’) confirming that FGFs act during a brief window of competence.

Together, these results show that FGF signaling is necessary and sufficient to specify precursors for GnRH-1 neurons in the olfactory placode. FGFs act during a narrow window of competence and thereafter GnRH-1 neurons become independent of this pathway.

Retinoic acid suppresses the production of GnRH-1 neurons

Complementary to FGF8 and Sprouty2, the retinoic acid-producing enzyme RALDH3 is expressed at the ventro-lateral aspect of the olfactory placode, away from the region where GnRH-1 neurons form (Fig. 2Ad; Fig. 4A, C). Do FGF and RA signaling antagonize each other to position GnRH-1 neurons? In the presence of the RA inhibitor Citral the production of GnRH-1+ and Hu+ cells is unaffected in olfactory placode explants (control: n=6; Citral: n=11; Fig. 3Da-b”). In contrast, these cells do not form in the presence of all-trans RA (control: n=5; RA: n=6; Fig. 3Dc-c”, e-e”). To assess whether GnRH-1 neurons continue to be sensitive to RA after their specification (i.e. after HH16/7), we cultured HH20 olfactory explants in the presence of RA: GnRH-1 neurons are still produced (n=12; Fig. 3D d, d’, f, f’). These results demonstrate that RA represses the formation of GnRH-1 precursors at the time of specification, but does not interfere with their subsequent development. Thus, both FGF and RA signaling act during a brief time window affecting GnRH-1 precursors, but not more mature GnRH-1 expressing cells.

This raises the possibility that at the time of GnRH-1 precursor specification, opposing functions of RA and FGF signaling may determine the site of GnRH-1 neuron production in the dorsal-medial aspect of the olfactory placode. To test whether RA and FGF signals indeed regulate each other, we manipulated both pathways in vivo. At HH16, RA or SU5402 coated or control beads were grafted next to the dorsal-medial edge of the olfactory placode, where FGF8 and Sprouty2 are expressed. When RA levels are elevated FGF8 (Fig. 4Ba; n=6) and Sprouty2 (not shown) expression are reduced after 12 hours, while RALDH3 expression expands when FGF signaling is inhibited (Fig. 4Bb, b’; n=9). Control beads (n=12) do not affect gene expression. Interestingly, just a few hours later (HH18) modulation of FGF and RA signaling does not affect the expression of these genes (not shown). This finding suggests that their antagonistic interaction is restricted to a very short time window corresponding to the time when GnRH-1 precursor specification takes place (HH16/17). We therefore propose a model in which FGF initiates GnRH-1 precursors (Fig. 4C, HH15/16), RA production begins slightly later (Fig. 4C, HH16/17) and inhibits their formation in the ventro-lateral olfactory placode. By HH18/16 FGF8 and RALDH3 expression domains abut, they negatively regulate each other and restrict GnRH-1 neuron production to the dorsal medial aspect of the olfactory placode (Fig. 4C; right).

Discussion

In vertebrates, hypothalamic GnRH-1 neurons perform critical functions in reproductive physiology and behavior: their disruption in humans results in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or Kallmann syndrome (KS) (Cariboni and Maggi, 2006; Wray, 2002). Here, we show that in the chick they arise in the olfactory placode, where they are specified through mutual antagonism of RA and FGF signaling. GnRH-1 precursor specification is under strict temporal control, being limited to a brief period after the formation of OSNs. Human KS has generally been attributed to a failure of GnRH-1 neuron migration, however our findings raise the possibility that at least in some patients these neurons may fail to be specified.

Origin of GnRH-1 neurons

The origin of GnRH-1 neurons remains controversial. Although numerous studies in amniotes indicate an olfactory placode origin (Daikoku-Ishido et al., 1990; el Amraoui and Dubois, 1993; Murakami and Arai, 1994a; Daikoku and Koide, 1998; Dellovade et al., 1998; Mulrenin et al., 1999; Suter et al., 2000) recent zebrafish data suggest that the anterior pituitary and neural crest, but not the olfactory placode, produces GnRH-1 neurons (Whitlock, 2004; Whitlock et al., 2006; Whitlock et al., 2003). While GnRH-1 neurons are normal in mice lacking the anterior pituitary (Metz and Wray, 2010), genetic lineage tracing of neural crest cells using Wnt1-Cre;R26RYFP/+ lines show contradictory results. One study reported no contribution of YFP+ cells to the olfactory epithelium or to neurons along the olfactory nerve (Barraud et al., 2010). The other showed variable, patchy YFP expression in the olfactory epithelium and in GnRH-1 neurons (Forni et al., 2011) suggesting that neural crest cells contribute to both. This is a very surprising finding, since a neural crest cell contribution to olfactory epithelial lineages has not been described previously (Couly and Le Douarin, 1987; Ericsson et al., 2008; Gross and Hanken, 2004; Inoue et al., 2000; Iwao et al., 2008; Le Douarin and Dupin, 1993; Le Douarin and Kalcheim, 1999). Using the same transgenic line, we find substantial variability of YFP expression including ectopic activity in the telencephalon and retina (unpublished observations), suggesting that YFP expression in Wnt1-Cre;R26RYFP/+ embryos should not be assumed to reflect neural crest origin. In contrast, our chick experiments yielded consistent results using two different fate-mapping methods: lineage labeling with vital dyes and tissue grafting from transgenic GFP donors to unlabelled hosts. In chick, neither the anterior pituitary nor neural crest cells generate GnRH-1 neurons, while the olfactory placode does. Although the olfactory nerve is surrounded by cells of neural crest origin, these cells do not invade the olfactory epithelium and have recently been identified as olfactory ensheathing cells (Barraud et al., 2010). We therefore conclude that GnRH-1 neurons arise in the olfactory placode.

Diversity of neuronal progenitors in the olfactory placode

The olfactory placode not only generates OSNs, but also migratory neurons including GnRH-1, somatostatin, calbindin, galanin and neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons (Abe et al., 1992; Hilal et al., 1996; Key and Wray, 2000; Murakami and Arai, 1994b; Tarozzo et al., 1994; Toba et al., 2001). Thus, modulators of the olfactory and reproductive system are already closely associated during development. In the adult, GnRH-1 neurons receive input from OSNs (Boehm et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2005), while NPY neurons regulate GnRH-1 release in the nervus terminalis and gonadotropin secretion in the anterior pituitary gland (Kalra and Crowley, 1992). In the olfactory bulb, somatostatin interneurons influence gamma oscillation in the olfactory network to modulate odor discrimination (Lepousez et al., 2010). Thus, primary olfactory neurons and neurons that modulate olfactory processing share a common embryonic origin and continuously interact during development. Their intimate relationship throughout embryogenesis may provide critical guidance cues to assemble neuronal circuits as a prerequisite for functional integration (Cariboni et al., 2007). This is reminiscent of ear development, where neurons originate from the same site as the sensory hair cells they later innervate (Bell et al., 2008), which in turn may be crucial for axon path finding and tonotopic innervation (Fekete and Campero, 2007; Rubel and Fritzsch, 2002).

How do GnRH-1 and OSNs become different from each other? Both require FGF signaling albeit at different times (Maier et al., 2010; this study). They appear to arise from common Sox2+ and Ascl1+ progenitors, however OSNs formation requires proneural and neuronal determination factors (Burns and Vetter, 2002; Cau et al., 2002; Cau et al., 2000; Cau et al., 1997; Maier and Gunhaga, 2009; Manglapus et al., 2004) absent in GnRH-1 neurons (Kramer and Wray, 2000). Several transcription factors among them Gata4, Otx2, Oct1 and members of the Dlx family control GnRH-1 expression (Givens et al., 2005; Kelley et al., 2000; Lawson and Mellon, 1998; Lawson et al., 1996; Rave-Harel et al., 2005). Otx2 mutations are associated with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism in humans and its deletion in GnRH-1 neurons eliminates a considerable proportion of these neurons (Diaczok et al., 2011). It is therefore possible that combinatorial expression of these factors specifies GnRH-1 neurons within the olfactory placode.

FGF signaling and GnRH-1 neurons

FGF signaling plays a crucial role throughout the development of GnRH-1 neurons. At early stages, FGFs mediate olfactory placode induction (Bailey et al., 2006) and later FGF8 is required for maintenance of the placode and its derivative, the vomeronasal organ (Kawauchi et al., 2005). In FGF8 hypomorphic mice, the olfactory epithelium is intact, but GnRH-1 neurons fail to emerge (Chung et al., 2008; Falardeau et al., 2008) presumably due to the absence of the vomeronasal organ, which is the source of GnRH-1 neurons in mouse (Wray et al., 1989b). In humans, FGF8 and FGFR1 mutations are associated with KS (Albuisson et al., 2005; Dode et al., 2003; Falardeau et al., 2008; Pitteloud et al., 2006; Zenaty et al., 2006) and in FGFR1 knock-out mice GnRH-1 neurons are reduced (Chung et al., 2008; Gill et al., 2004; Tsai et al., 2005). Finally, FGF signaling plays a role in patterning the olfactory placode by promoting medial fates (Tucker et al., 2010). Thus, although FGFs have previously been implicated in GnRH-1 neuron development, our studies are the first to provide direct evidence that the FGF pathway is required for their initial specification during a very narrow time window. Human KS is generally attributed to a failure of GnRH-1 neuron migration, however our results indicate that KS may also be due to a lack of specification.

A complex interplay of FGF and RA signaling

To form a functional sensory nervous system peripheral and central components must develop in register. This is particularly apparent in the face where alignment of sensory structures with the corresponding parts of the brain is accompanied by complex morphogenetic events. In this context, FGF and RA pathways interact repeatedly to coordinate morphogenesis of the forebrain and the facial ectoderm, including the olfactory placode and bulb. At early stages, ectoderm-derived RA signals via neural crest cells to maintain the expression of FGF8 in the telencephalon and the cranial ectoderm (Schneider et al., 2001); (Hu and Marcucio, 2009).

In contrast, RA and FGF pathways oppose each other slightly later to pattern the olfactory placode and to regulate the transition from self-renewing to neurogenic progenitor cells. At the lateral rim of the placode RA promotes lateral olfactory fates and maintains slowly dividing progenitors, while suppressing medial character and rapidly dividing progenitors. In contrast, medial FGF signaling has opposite effects (LaMantia et al., 2000; LaMantia et al., 1993; Rawson et al., 2010; Tucker et al., 2010). Here we show that GnRH-1 neurons emerging dorso-medially require active FGF signaling and are repressed by RA (Fig. 4C). Their antagonistic interaction may be due to negative cross-regulation: inhibition of FGF signaling expands RALDH3, while an excess of RA represses FGF activity. The olfactory nerve forms a substrate for migrating GnRH-1 neurons and projects to the anterior telencephalon; here it initiates olfactory bulb formation in an FGF-dependent manner together with continued RA signaling from the neural crest (Anchan et al., 1997; Crossley et al., 2001; Fukuchi-Shimogori and Grove, 2001; Hebert et al., 2003; LaMantia et al., 1993; Meyers et al., 1998).

Finally, when the nasal pits are well invaginated, RA and FGF signaling appear to act in a positive feedback loop. FGF8 expression expands laterally and is now dependent on RA (Szabo-Rogers et al., 2008) and vice versa (unpublished observations). Thus, a complex interplay of RA and FGF signaling coordinates olfactory placode patterning and neurogenesis with the formation of its central target, the olfactory bulb.

The opposing action of RA and FGF signaling appears to emerge as a common theme in regulating neuronal differentiation. In the elongating spinal cord and in embryonic stem cells, FGF activity ensures continued proliferation of progenitor cells, while RA initiates neuronal differentiation (Diez del Corral et al., 2003; Diez del Corral and Storey, 2004; Sockanathan et al., 2003; Stavridis et al., 2010). In the olfactory placode, the molecular interactions are conserved, while the processes they control differ. The FGF pathway maintains a pool of progenitors (Kawauchi et al., 2005) and promotes GnRH-1 neurons (Fig. 4C), while RA inhibits differentiation and maintains self-renewing progenitors before they commit to neurogenesis.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Helen Sang and Adrian Sherman for providing fertilized GFP chick eggs and to Claudio D. Stern and J. Parnavelas for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by BBSRC (D010659) and Wellcome Trust (081531) grants and an MRC studentship to A.S., by Wellcome Trust grant 082556 to C.V.H.B. and Wellcome Trust grant 091555 to C.V.H.B. and P.B. Thanks to Anastasia Seferiadis for preliminary work on this project, funded by Wellcome Trust grant 078087 to C.V.H.B.

References

- Abe H, Watanabe M, Kondo H. Developmental changes in expression of a calcium-binding protein (spot 35-calbindin) in the Nervus terminalis and the vomeronasal and olfactory receptor cells. Acta Otolaryngol. 1992;112:862–871. doi: 10.3109/00016489209137485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham E, Palevitch O, Gothilf Y, Zohar Y. The zebrafish as a model system for forebrain GnRH neuronal development. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;164:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with Image J. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Albuisson J, Pecheux C, Carel JC, Lacombe D, Leheup B, Lapuzina P, Bouchard P, Legius E, Matthijs G, Wasniewska M, Delpech M, Young J, Hardelin JP, Dode C. Kallmann syndrome: 14 novel mutations in KAL1 and FGFR1 (KAL2) Hum Mutat. 2005;25:98–99. doi: 10.1002/humu.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anchan RM, Drake DP, Haines CF, Gerwe EA, LaMantia AS. Disruption of local retinoid-mediated gene expression accompanies abnormal development in the mammalian olfactory pathway [published erratum appears in J Comp Neurol 1997 Jul 28;384(2):321] J Comp Neurol. 1997;379:171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AP, Bhattacharyya S, Bronner-Fraser M, Streit A. Lens specification is the ground state of all sensory placodes, from which FGF promotes olfactory identity. Dev Cell. 2006;11:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CV, Bronner-Fraser M. Vertebrate cranial placodes I. Embryonic induction. Dev Biol. 2001;232:1–61. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud P, Seferiadis AA, Tyson LD, Zwart MF, Szabo-Rogers HL, Ruhrberg C, Liu KJ, Baker CV. Neural crest origin of olfactory ensheathing glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21040–21045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012248107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beites CL, Kawauchi S, Crocker CE, Calof AL. Identification and molecular regulation of neural stem cells in the olfactory epithelium. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D, Streit A, Gorospe I, Varela-Nieto I, Alsina B, Giraldez F. Spatial and temporal segregation of auditory and vestibular neurons in the otic placode. Dev Biol. 2008;322:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S, Bailey AP, Bronner-Fraser M, Streit A. Segregation of lens and olfactory precursors from a common territory: cell sorting and reciprocity of Dlx5 and Pax6 expression. Dev Biol. 2004;271:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blentic A, Gale E, Maden M. Retinoic acid signalling centres in the avian embryo identified by sites of expression of synthesising and catabolising enzymes. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:114–127. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm U, Zou Z, Buck LB. Feedback loops link odor and pheromone signaling with reproduction. Cell. 2005;123:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns CJ, Vetter ML. Xath5 regulates neurogenesis in the Xenopus olfactory placode. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:536–543. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calof AL, Bonnin A, Crocker C, Kawauchi S, Murray RC, Shou J, Wu HH. Progenitor cells of the olfactory receptor neuron lineage. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;58:176–188. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariboni A, Maggi R. Kallmann’s syndrome, a neuronal migration defect. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2512–2526. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5604-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariboni A, Maggi R, Parnavelas JG. From nose to fertility: the long migratory journey of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Casarosa S, Guillemot F. Mash1 and Ngn1 control distinct steps of determination and differentiation in the olfactory sensory neuron lineage. Development. 2002;129:1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Gradwohl G, Casarosa S, Kageyama R, Guillemot F. Hes genes regulate sequential stages of neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium. Development. 2000;127:2323–2332. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 activates a cascade of bHLH regulators in olfactory neuron progenitors. Development. 1997;124:1611–1621. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Chung J, Han J, Ju Lee B, Han Kim D, Rhee K, Kim K. 9-cis- Retinoic acid represses transcription of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene via proximal promoter region that is distinct from all-trans-retinoic acid response element. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001a;87:214–222. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Chung JJ, Choe Y, Choi HS, Han Kim D, Rhee K, Kim K. A functional retinoic acid response element (RARE) is present within the distal promoter of the rat gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001b;87:204–213. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WC, Moyle SS, Tsai PS. Fibroblast growth factor 8 signaling through fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is required for the emergence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4997–5003. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couly G, Le Douarin NM. The fate map of the cephalic neural primordium at the presomitic to the 3-somite stage in the avian embryo. Development. 1988;103:101–113. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couly GF, Le Douarin NM. Mapping of the early neural primordium in quail-chick chimeras. I. Developmental relationships between placodes, facial ectoderm, and prosencephalon. Dev Biol. 1985;110:422–439. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couly GF, Le Douarin NM. Mapping of the early neural primordium in quail-chick chimeras. II. The prosencephalic neural plate and neural folds: implications for the genesis of cephalic human congenital abnormalities. Dev Biol. 1987;120:198–214. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley PH, Martinez S, Ohkubo Y, Rubenstein JL. Coordinate expression of Fgf8, Otx2, Bmp4, and Shh in the rostral prosencephalon during development of the telencephalic and optic vesicles. Neuroscience. 2001;108:183–206. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku-Ishido H, Okamura Y, Yanaihara N, Daikoku S. Development of the hypothalamic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-containing neuron system in the rat: in vivo and in transplantation studies. Dev Biol. 1990;140:374–387. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90087-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku S, Koide I. Spatiotemporal appearance of developing LHRH neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:34–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980330)393:1<34::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellovade TL, Pfaff DW, Schwanzel-Fukuda M. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone system does not develop in Small-Eye (Sey) mouse phenotype. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;107:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaczok D, Divall S, Matsuo I, Wondisford FE, Wolfe AM, Radovick S. Deletion of Otx2 in GnRH Neurons Results in a Mouse Model of Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:833–846. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez del Corral R, Olivera-Martinez I, Goriely A, Gale E, Maden M, Storey K. Opposing FGF and retinoid pathways control ventral neural pattern, neuronal differentiation, and segmentation during body axis extension. Neuron. 2003;40:65–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez del Corral R, Storey KG. Opposing FGF and retinoid pathways: a signalling switch that controls differentiation and patterning onset in the extending vertebrate body axis. Bioessays. 2004;26:857–869. doi: 10.1002/bies.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode C, Levilliers J, Dupont JM, De Paepe A, Le Du N, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Coimbra RS, Delmaghani S, Compain-Nouaille S, Baverel F, Pecheux C, Le Tessier D, Cruaud C, Delpech M, Speleman F, Vermeulen S, Amalfitano A, Bachelot Y, Bouchard P, Cabrol S, Carel JC, Delemarre-van de Waal H, Goulet-Salmon B, Kottler ML, Richard O, Sanchez-Franco F, Saura R, Young J, Petit C, Hardelin JP. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:463–465. doi: 10.1038/ng1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C, Torello AT. Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals: from genes to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:551–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Amraoui A, Dubois PM. Experimental evidence for an early commitment of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons, with special regard to their origin from the ectoderm of nasal cavity presumptive territory. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:991–1002. doi: 10.1159/000126490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson R, Joss J, Olsson L. The fate of cranial neural crest cells in the Australian lungfish, Neoceratodus forsteri. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2008;310:345–354. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falardeau J, Chung WC, Beenken A, Raivio T, Plummer L, Sidis Y, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Eliseenkova AV, Ma J, Dwyer A, Quinton R, Na S, Hall JE, Huot C, Alois N, Pearce SH, Cole LW, Hughes V, Mohammadi M, Tsai P, Pitteloud N. Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2822–2831. doi: 10.1172/JCI34538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete DM, Campero AM. Axon guidance in the inner ear. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:549–556. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072341df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forni PE, Taylor-Burds C, Melvin VS, Williams T, Wray S. Neural Crest and Ectodermal Cells Intermix in the Nasal Placode to Give Rise to GnRH-1 Neurons, Sensory Neurons, and Olfactory Ensheathing Cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6915–6927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6087-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi-Shimogori T, Grove EA. Neocortex patterning by the secreted signaling molecule FGF8. Science. 2001;294:1071–1074. doi: 10.1126/science.1064252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill JC, Moenter SM, Tsai PS. Developmental regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by fibroblast growth factor signaling. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3830–3839. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens ML, Rave-Harel N, Goonewardena VD, Kurotani R, Berdy SE, Swan CH, Rubenstein JL, Robert B, Mellon PL. Developmental regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene expression by the MSX and DLX homeodomain protein families. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19156–19165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC. GnRH: The Master Molecule of Reproduction. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Norwell, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JB, Hanken J. Use of fluorescent dextran conjugates as a long-term marker of osteogenic neural crest in frogs. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:100–106. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guner B, Ozacar AT, Thomas JE, Karlstrom RO. Graded Hedgehog and Fibroblast Growth Factor Signaling Independently Regulate Pituitary Cell Fates and Help Establish the Pars Distalis and Pars Intermedia of the Zebrafish Adenohypophysis 10.1210/en.2008-0315. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4435–4451. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morph. 1951;88:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert JM, Lin M, Partanen J, Rossant J, McConnell SK. FGF signaling through FGFR1 is required for olfactory bulb morphogenesis. Development. 2003;130:1101–1111. doi: 10.1242/dev.00334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog W, Sonntag C, von der Hardt S, Roehl HH, Varga ZM, Hammerschmidt M. Fgf3 signaling from the ventral diencephalon is required for early specification and subsequent survival of the zebrafish adenohypophysis. Development. 2004;131:3681–3692. doi: 10.1242/dev.01235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilal EM, Chen JH, Silverman AJ. Joint migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons from olfactory placode to central nervous system. J Neurobiol. 1996;31:487–502. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199612)31:4<487::AID-NEU8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Marcucio RS. A SHH-responsive signaling center in the forebrain regulates craniofacial morphogenesis via the facial ectoderm. Development. 2009;136:107–116. doi: 10.1242/dev.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Nakamura S, Osumi N. Fate mapping of the mouse prosencephalic neural plate. Dev Biol. 2000;219:373–383. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwao K, Inatani M, Okinami S, Tanihara H. Fate mapping of neural crest cells during eye development using a protein 0 promoter-driven transgenic technique. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1117–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennes L, Conn PM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone. In: Pfaff DW, Arnold AP, Etgen AM, Farhbach SE, Rubin RT, editors. Hormones, Brain and Behaviour. Academic Press; New York: 2002. pp. 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra SP, Crowley WR. Neuropeptide Y: a novel neuroendocrine peptide in the control of pituitary hormone secretion, and its relation to luteinizing hormone. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1992;13:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi S, Shou J, Santos R, Hebert JM, McConnell SK, Mason I, Calof AL. Fgf8 expression defines a morphogenetic center required for olfactory neurogenesis and nasal cavity development in the mouse. Development. 2005;132:5211–5223. doi: 10.1242/dev.02143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley CG, Lavorgna G, Clark ME, Boncinelli E, Mellon PL. The Otx2 homeoprotein regulates expression from the gonadotropin-releasing hormone proximal promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1246–1256. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key S, Wray S. Two olfactory placode derived galanin subpopulations: luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurones and vomeronasal cells. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:535–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PR, Wray S. Midline nasal tissue influences nestin expression in nasal- placode-derived luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons during development. Dev Biol. 2000;227:343–357. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMantia AS, Bhasin N, Rhodes K, Heemskerk J. Mesenchymal/epithelial induction mediates olfactory pathway formation. Neuron. 2000;28:411–425. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMantia AS, Colbert MC, Linney E. Retinoic acid induction and regional differentiation prefigure olfactory pathway formation in the mammalian forebrain. Neuron. 1993;10:1035–1048. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90052-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, Mellon PL. Expression of GATA-4 in migrating gonadotropin-releasing neurons of the developing mouse. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;140:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, Whyte DB, Mellon PL. GATA factors are essential for activity of the neuron-specific enhancer of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3596–3605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM. Cell line segregation during peripheral nervous system ontogeny. Science. 1986;231:1515–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.3952494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Dupin E. Cell lineage analysis in neural crest ontogeny. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:146–161. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Kalcheim C. The neural crest. 2nd ed Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lepousez G, Mouret A, Loudes C, Epelbaum J, Viollet C. Somatostatin contributes to in vivo gamma oscillation modulation and odor discrimination in the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2010;30:870–875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4958-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livne I, Gibson MJ, Silverman AJ. Brain grafts of migratory GnRH cells induce gonadal recovery in hypogonadal (hpg) mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1992a;69:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90128-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livne I, Silverman AJ, Gibson MJ. Reversal of reproductive deficiency in the hpg male mouse by neonatal androgenization. Biol Reprod. 1992b;47:561–567. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod47.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier E, Gunhaga L. Dynamic expression of neurogenic markers in the developing chick olfactory epithelium. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1617–1625. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier E, von Hofsten J, Nord H, Fernandes M, Paek H, Hebert JM, Gunhaga L. Opposing Fgf and Bmp activities regulate the specification of olfactory sensory and respiratory epithelial cell fates. Development. 2010;137:1601–1611. doi: 10.1242/dev.051219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglapus GL, Youngentob SL, Schwob JE. Expression patterns of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors define subsets of olfactory progenitor cells. J Comp Neurol. 2004;479:216–233. doi: 10.1002/cne.20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason AJ, Hayflick JS, Zoeller RT, Young WS, 3rd, Phillips HS, Nikolics K, Seeburg PH. A deletion truncating the gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene is responsible for hypogonadism in the hpg mouse. Science. 1986;234:1366–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.3024317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew MJ, Sherman A, Lillico SG, Ellard FM, Radcliffe PA, Gilhooley HJ, Mitrophanous KA, Cambray N, Wilson V, Sang H. Localised axial progenitor cell populations in the avian tail bud are not committed to a posterior Hox identity. Development. 2008;135:2289–2299. doi: 10.1242/dev.022020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith M. Vomeronasal, olfactory, hormonal convergence in the brain. Cooperation or coincidence? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;855:349–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz H, Wray S. Use of mutant mouse lines to investigate origin of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neurons: lineage independent of the adenohypophysis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:766–773. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR. An Fgf8 mutant allelic series generated by Cre- and Flp-mediated recombination. Nat Genet. 1998;18:136–141. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima N, Tomarev S. Chicken Eyes absent 2 gene: isolation and expression pattern during development. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42:1109–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulrenin EM, Witkin JW, Silverman AJ. Embryonic development of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) system in the chick: a spatio-temporal analysis of GnRH neuronal generation, site of origin, and migration. Endocrinology. 1999;140:422–433. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Arai Y. Direct evidence for the migration of LHRH neurons from the nasal region to the forebrain in the chick embryo: a carbocyanine dye analysis. Neurosci Res. 1994a;19:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Arai Y. Transient expression of somatostatin immunoreactivity in the olfactory-forebrain region in the chick embryo. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1994b;82:277–285. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren RB, Jr., Lehman MN. Neurons that migrate from the olfactory epithelium in the chick express luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1676–1678. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-3-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palevitch O, Kight K, Abraham E, Wray S, Zohar Y, Gothilf Y. Ontogeny of the GnRH systems in zebrafish brain: in situ hybridization and promoter-reporter expression analyses in intact animals. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:313–322. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitteloud N, Meysing A, Quinton R, Acierno JS, Jr., Dwyer AA, Plummer L, Fliers E, Boepple P, Hayes F, Seminara S, Hughes VA, Ma J, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley WF., Jr. Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 cause Kallmann syndrome with a wide spectrum of reproductive phenotypes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254-255:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rave-Harel N, Miller NL, Givens ML, Mellon PL. The Groucho-related gene family regulates the gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene through interaction with the homeodomain proteins MSX1 and OCT1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30975–30983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502315200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson NE, Lischka FW, Yee KK, Peters AZ, Tucker ES, Meechan DW, Zirlinger M, Maynard TM, Burd GB, Dulac C, Pevny L, LaMantia AS. Specific mesenchymal/epithelial induction of olfactory receptor, vomeronasal, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1723–1738. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EW, Fritzsch B. Auditory system development: primary auditory neurons and their targets. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:51–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser G. Induction and specification of cranial placodes. Dev Biol. 2006;294:303–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RA, Hu D, Rubenstein JL, Maden M, Helms JA. Local retinoid signaling coordinates forebrain and facial morphogenesis by maintaining FGF8 and SHH. Development. 2001;128:2755–2767. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Pfaff DW. Origin of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Nature. 1989;338:161–164. doi: 10.1038/338161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman AJ, Livne I, Witkin JW. The gonadotropin-releaseing hormone (GnRH) neuronal systems: immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. In: Knobil E, Neill J, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 1683–1709. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk CL, Foster DL. The neural basis of puberty and adolescence. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1040–1047. doi: 10.1038/nn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockanathan S, Perlmann T, Jessell TM. Retinoid receptor signaling in postmitotic motor neurons regulates rostrocaudal positional identity and axonal projection pattern. Neuron. 2003;40:97–111. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Hui JN, Fu KK, Richman JM. Control of retinoic acid synthesis and FGF expression in the nasal pit is required to pattern the craniofacial skeleton. Dev Biol. 2004;276:313–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavridis MP, Collins BJ, Storey KG. Retinoic acid orchestrates fibroblast growth factor signalling to drive embryonic stem cell differentiation. Development. 2010;137:881–890. doi: 10.1242/dev.043117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A. Extensive cell movements accompany formation of the otic placode. Dev Biol. 2002;249:237–254. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A. The preplacodal region: an ectodermal domain with multipotential progenitors that contribute to sense organs and cranial sensory ganglia. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:447–461. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072327as. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A, Sockanathan S, Perez L, Rex M, Scotting PJ, Sharpe PT, Lovell-Badge R, Stern CD. Preventing the loss of competence for neural induction: HGF/SF, L5 and Sox-2. Development. 1997;124:1191–1202. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.6.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter KJ, Song WJ, Sampson TL, Wuarin JP, Saunders JT, Dudek FE, Moenter SM. Genetic targeting of green fluorescent protein to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: characterization of whole-cell electrophysiological properties and morphology. Endocrinology. 2000;141:412–419. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo-Rogers HL, Geetha-Loganathan P, Nimmagadda S, Fu KK, Richman JM. FGF signals from the nasal pit are necessary for normal facial morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;318:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarozzo G, Peretto P, Perroteau I, Andreone C, Varga Z, Nicholls J, Fasolo A. GnRH neurons and other cell populations migrating from the olfactory neuroepithelium. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 1994;55:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toba Y, Ajiki K, Horie M, Sango K, Kawano H. Immunohistochemical localization of calbindin D-28k in the migratory pathway from the rat olfactory placode. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:683–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai PS, Moenter SM, Postigo HR, El Majdoubi M, Pak TR, Gill JC, Paruthiyil S, Werner S, Weiner RI. Targeted expression of a dominant-negative fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons reduces FGF responsiveness and the size of GnRH neuronal population. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:225–236. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker ES, Lehtinen MK, Maynard T, Zirlinger M, Dulac C, Rawson N, Pevny L, Lamantia AS. Proliferative and transcriptional identity of distinct classes of neural precursors in the mammalian olfactory epithelium. Development. 2010;137:2471–2481. doi: 10.1242/dev.049718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock KE. A new model for olfactory placode development. Brain Behav Evol. 2004;64:126–140. doi: 10.1159/000079742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock KE, Illing N, Brideau NJ, Smith KM, Twomey S. Development of GnRH cells: Setting the stage for puberty. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254-255:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock KE, Wolf CD, Boyce ML. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) cells arise from cranial neural crest and adenohypophyseal regions of the neural plate in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Dev Biol. 2003;257:140–152. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S. Development of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:292–316. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3022(02)00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S, Grant P, Gainer H. Evidence that cells expressing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone mRNA in the mouse are derived from progenitor cells in the olfactory placode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989a;86:8132–8136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S, Nieburgs A, Elkabes S. Spatiotemporal cell expression of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in the prenatal mouse: evidence for an embryonic origin in the olfactory placode. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1989b;46:309–318. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Dude CM, Baker CVH. Fine-grained fate maps for the ophthalmic and maxillomandibular trigeminal placodes in the chick embryo. Developmental Biology. 2008;317:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Enquist LW, Dulac C. Olfactory inputs to hypothalamic neurons controlling reproduction and fertility. Cell. 2005;123:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenaty D, Bretones P, Lambe C, Guemas I, David M, Leger J, de Roux N. Paediatric phenotype of Kallmann syndrome due to mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254-255:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]