Abstract

The mucosal surfaces of wild and farmed aquatic vertebrates face the threat of many aquatic pathogens, including fungi. These surfaces are colonized by diverse symbiotic bacterial communities that may contribute to fight infection. Whereas the gut microbiome of teleosts has been extensively studied using pyrosequencing, this tool has rarely been employed to study the compositions of the bacterial communities present on other teleost mucosal surfaces. Here we provide a topographical map of the mucosal microbiome of an aquatic vertebrate, the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Using 16S rRNA pyrosequencing, we revealed novel bacterial diversity at each of the five body sites sampled and showed that body site is a strong predictor of community composition. The skin exhibited the highest diversity, followed by the olfactory organ, gills, and gut. Flectobacillus was highly represented within skin and gill communities. Principal coordinate analysis and plots revealed clustering of external sites apart from internal sites. A highly diverse community was present within the epithelium, as demonstrated by confocal microscopy and pyrosequencing. Using in vitro assays, we demonstrated that two Arthrobacter sp. skin isolates, a Psychrobacter sp. strain, and a combined skin aerobic bacterial sample inhibit the growth of Saprolegnia australis and Mucor hiemalis, two important aquatic fungal pathogens. These results underscore the importance of symbiotic bacterial communities of fish and their potential role for the control of aquatic fungal diseases.

INTRODUCTION

The mucosal surfaces of vertebrate animals are at the interface between the environment and the animal host. Mucosal epithelia form important mechanical and chemical barriers that prevent pathogen invasion but permit colonization by symbiotic microorganisms, the microbiota. The microbiota is crucial for the development, homeostasis, and immune function of an animal's mucosal epithelia (1, 2, 3).

The associations between metazoans and commensal microorganisms are among the most ancient and successful associations found in nature (4, 5). The microbial communities of different organisms, such as plants, corals, annelids, gastropods, insects, and many vertebrates, are being characterized. In the particular case of vertebrates, mucosal surfaces have undergone drastic changes over the course of evolution due to the transition of vertebrate animals from water to land. These evolutionary pressures especially affected some mucosal barriers, such as the skin. While the skin of fish is a living cell layer that secretes a mucous layer and has imbricated scales for protection (6), amphibians have a cornified layer of skin that has developed into a more uniform epidermis (6). Finally, in birds and mammals, the presence of feathers, scales, hair, sweat glands, coats, or the leather-like thickening of the dermis represents unique adaptations to terrestrial environments. All these structures and appendages, in turn, provide unique niches within the skin for microbial colonization (6, 7).

All vertebrates have a complex adaptive immune system in association with their mucosal epithelia. It has been proposed that adaptive immunity may have evolved as a result of the complex symbiotic microbial communities that vertebrates harbor in mucosal sites (8). The vertebrate transition from water to land likely affected the relationships between hosts and their microbiota. Water is a microbially rich environment that promotes bacterial growth compared to air. In other words, aquatic vertebrates have evolved mechanisms to benefit from symbiotic bacteria in an external environment where these microorganisms thrive. These symbiotic bacteria help aquatic hosts to fight against mucosal pathogens. For example, the mucosal microbiota of aquatic vertebrates can function to protect against fungal pathogens such as the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, affecting amphibians (9), or Saprolegnia sp. affecting fish and amphibians (10, 11). It is clear that the mucosal surfaces of wild and farmed aquatic vertebrates along with their associated microbiota play a critical role in the control of aquatic diseases.

The Human Microbiome Project has offered revolutionary insights into the different microbial communities present at different mucosal surfaces (12, 13, 14). While the gut is by far the best-characterized site, it is now clear that distinct microbial communities inhabit different anatomical sites, such as the gut, mouth, skin, and vaginal cavity, and each site contains different ratios of major groups of bacteria (15). Thus, body site is a strong determinant factor for the composition of the microbiota in terrestrial vertebrates. However, detailed topographical maps of these communities in other animal species are currently missing. The main mucosal barriers of teleost fish are the gut, skin, and gills, and they form the interface between the host and its environment. Teleost fish gut, skin, and gills are known to harbor complex microbial communities (16, 17). Though there have been a number of studies on the intestinal microbiomes of teleosts (18, 19, 20, 21), the diversity present at other mucosal sites remains largely unexplored in the majority of teleost species.

The purpose of this study was to fingerprint the microbial communities present on five mucosal surfaces of healthy adult hatchery-reared rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) using high-throughput sequencing. We provide a topographical map of the microbiome of a teleost species and identify resident strains that have antifungal properties against two different fungal pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissue samples.

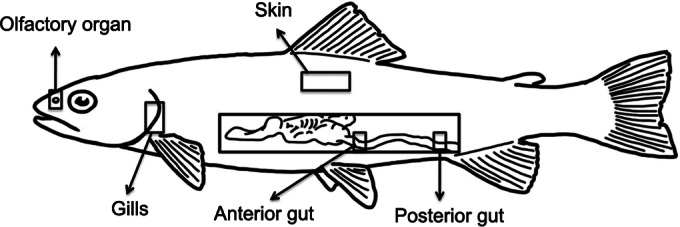

Six hatchery-reared adult female triploid rainbow trout (O. mykiss) were obtained from the Lisboa Springs Hatchery in Pecos, NM. The average length of the fish was 28.5 ± 2.7 cm from head to tail, and the mean weight was approximately 250 ± 6.2 g. Fish were maintained in the hatchery raceways in an open water circulation system from the Pecos River. Sampling was conducted in October 2012, when water temperatures are approximately 13°C. Fish were starved for 48 h prior to sampling. Rainbow trout were first euthanized using an overdose of MS-222 (100 mg/liter). Skin, gills, olfactory rosettes, and anterior gut and posterior gut tissue samples were collected. The sampling scheme was selected based on the main physiological and physicochemical properties of these sites, which are likely to generate different habitats for bacteria. Skin samples were 1 cm2 and were obtained above the lateral line on the left side of the fish. Gill samples were taken from the second left gill arch for consistency purposes. Both olfactory rosettes were removed from the olfactory cavity after removing the skin covering. Anterior gut samples (1 cm long) were collected immediately after the stomach, whereas posterior gut samples (1 cm long) were obtained 1 cm before the anus. Figure 1 shows the sampling scheme used in the present study. Samples were placed in sterile sucrose lysis buffer and stored at −80°C until processing.

FIG 1.

Diagram of the tissue sampling strategy for the present study.

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of New Mexico, protocol number 12-100854-MCC.

DNA isolation, bacterial 16S rRNA PCR amplification, and pyrosequencing.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from whole tissue samples, including both fish and bacterial DNA. Sterile 3-mm tungsten carbide beads (Qiagen) were used to lyse the tissue samples in a TissueLyser II (Qiagen) and create a homogenous mixture. For extraction, we followed the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) buffer method as previously described (22). DNA pellets were then resuspended in 30 μl of DNase- and RNase-free molecular-biology-grade water. Sample DNA concentration and purity was measured in a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000c.

Bacterial community composition was determined using barcoded pyrosequencing. Fourteen 12-bp barcodes were used to provide high-throughput analysis. Total genomic DNA extracted from the mucosal tissues was amplified in triplicate using barcoded V1-V3 16S rRNA gene primers (A17F, 5′-GTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′, and 519R, 5′-GTATTACCGCGGCAGCTGGCAC-3′) (23), with initial activation of the enzyme at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 33 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min 30 s. Amplification finished with a 10-min extension cycle at 72°C. In the event that amplification did not occur using the original A17F and 519R primers, a seminested PCR was used, with the first round consisting of the original forward primer, A17F, and the reverse primer P934R, 5′-ACCGCTTGTGCGGGYC-3′ (with Y being C or T). After amplification of this larger band, a seminested PCR with the original primers, A17F and 519R, was run. This process occurred for only 2 samples, a skin sample and a gill sample (fish 5 and 2, respectively). We still were unable to amplify the 16S rRNA from three samples, and these have been omitted from the study. Out of the six fish samples for each mucosal site, one anterior gut, one olfactory organ, and one skin sample failed to amplify the 16S rRNA. Those samples were therefore not included in our analyses.

A single band of approximately 500 bp was extracted after amplification using the Invitrogen E-Gel SizeSelect system. After gel extraction and purification, samples were pooled into libraries and sequenced on a Roche 454 GS FLX platform with titanium reagents at the Molecular Biology Facility at the University of New Mexico.

Sequence analysis.

In order to account for 454 sequencing base errors, as well as errors due to PCR amplification, and low-quality products, the final sequences from the Roche 454 GS FLX titanium platform were processed with Ampliconnoise (24). This included chimera checking with Perseus (24). All sequence analyses were performed in Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME; version 1.8) pipeline (25) with default settings. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were aligned to the Greengenes August 2013 (26) database at 97% identity, and those that did not match were subsampled at 10% of the failed aligned reads and clustered to determine new reference OTUs. Taxonomic summaries were produced to compare bacteria occurring at the five body sites sampled and the epithelial layer obtained by laser capture microdissection (LCM), described below.

To determine the level of sequencing depth, rarefaction curve analysis was conducted using QIIME. The lowest number of reads for all of our samples was 1,600 sequences, so for consistency purposes, we rarefied all samples to this depth. Alpha diversity metrics included Shannon diversity index, chao1, PD, Good's coverage, and number of OTUs, as well as number of phyla and genera. These metrics were compared between body sites. Microbial diversity between samples (beta-diversity) was evaluated with QIIME using weighted and unweighted UniFrac (27). Principal coordinate analysis, core microbiota analysis, and unique-OTU analysis were also performed in QIIME.

Comparison with Antifungal Isolates Database from amphibians.

We compared our results with the Antifungal Isolates Database (28), including 1,255 16S rRNA gene sequences from cultured bacteria isolated from amphibian skin using published data sets (28). A number of studies have tested these isolates for bioactivity against fungal pathogens, including Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, Mariannaea elegans, and Rhizomucor variabilis, in coculture challenge assays (9, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35). Because freshwater fish have mucosal defenses and fungal pathogens similar to those in amphibians, we used this database to generate a list of OTUs by clustering sequences at 97% similarity using the Greengenes August 2013 reference. This list was expanded to include neighboring OTUs within a Jukes-Cantor distance of 0.1 on the Greengenes phylogenetic tree (7,266 OTUs). We then filtered our OTU table in this study to retain only the matching OTUs (180 OTUs found). We compared the relative abundances of these 180 OTUs among the five trout body sites sampled and tested for differences among sites by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Matching 16S rRNA sequences do not indicate which other genes the isolates have in common, and isolates may not have matching function (36). Rather, this analysis aimed to show (i) which trout body site had bacteria similar to those found on amphibian skin and (ii) whether trout host bacteria are taxonomically similar to the antifungal isolates described from amphibians.

Saprolegnia australis and Mucor hiemalis isolation and identification.

Fungal pathogens were isolated from gill samples from juvenile summer steelhead rainbow trout at Salmon River Hatchery, OR (provided by J. Bartholomew), and a bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus, egg clutch from Naperville, VA (provided by G. Ruthig). Steelhead trout were raised on coastal river water in raceways in Oregon. The presence of fungal infections on fish skin and gills is not uncommon at this facility. Gill samples from diseased fish suspected of having fungal infection were cultured onto 30% cornmeal agar supplemented with 10% glucose and 100 mg/liter of enrofloxacin (to inhibit bacterial growth). Since Saprolegnia spp. are also common egg pathogens of amphibians (37), we sampled a clutch of bullfrog eggs that showed fungal growth. Fungal isolates were subcultured and total DNA was extracted. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of fungal ribosomal DNA (rDNA) was amplified using primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) as explained elsewhere (38, 39). Cloning and sequencing of the PCR products were performed as previously described (40). Recovered sequences were analyzed using BLAST.

Skin bacterial isolates and fungal inhibition assays.

A total of seven skin bacterial isolates were tested for inhibition of M. hiemalis and S. australis. Six of these isolates were obtained by streaking the skin mucus of hatchery rainbow trout onto Luria-Bertani agar plates. The seventh strain, Flectobacillus major, was obtained from the ATCC (ATCC 29496) and grown as per ATCC instructions. The combined aerobic skin bacterial samples were isolated as explained elsewhere (17). Bacteria and pathogens were grown and tested at 21°C. Bacteria were grown on R2A–0.5% tryptone agar plates. Agar plates were rinsed with 3 ml of water, and cell-free supernatant was collected after filtering through a 0.22-μm syringe filter from all bacterial cultures and control sterile media. The components of the cell-free supernatants causing antifungal activity were not investigated in this study.

Two nonquantitative antifungal assays were performed. First, a plug of the agar with actively growing fungus was placed on a new plate, and sterile antimicrobial susceptibility discs soaked in cell-free supernatant from each bacterial isolate or a blank were then added adjacent to the fungus. Plates were examined for zones of inhibition every 12 h for 4 days. Second, in addition to cell-free-supernatant assays, the fungus was cocultured with live bacteria by streaking the bacterium adjacent to the fungus and examining plates for zones of fungal inhibition. Zones of inhibition were not measured because they depended on the time of measurement and concentration of cell-free supernatant; thus, this was a qualitative assessment of growth inhibition.

To quantify the growth inhibition of M. hiemalis, the fungus was first grown for 5 days in 1% yeast mold (YM) broth. The fungus was then added to a 96-well plate (50 μl of fungus culture in 1% YM broth), and 50 μl of cell-free supernatant was added to each of 3 wells per isolate. Positive control wells included fungus plus water filtered after rinsing across a sterile R2A–0.5% tryptone agar plate. Negative-control wells consisted of heat-killed fungus (15 min at 75°C) or cycloheximide (at 500 or 50 μg/ml). The two treatments performed similarly (all cells were killed), and changes in optical density (OD) were not significantly different between the methods. Cycloheximide was not effective at concentrations of ≤5 μg/ml. All wells had a total of 100 μl, and growth was measured by quantifying the change in optical density at 400 nm over 20 h. We noted samples that caused complete growth inhibition as showing a change in OD that was not significantly different from that in negative-control wells by independent t test. The identities of isolates that showed inhibitory properties were determined using two methods: matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Tricore Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM) and sequencing of the 16S rDNA using the P46 forward primer and P943 reverse primers (P46 forward, 5′-GCYTAAYACATGCAAGTCG-3′, and P943 reverse, 5′-ACCGCTTGTGCGGGYCC-3′). The identification of the isolates by MALDI-TOF MS was performed on a Microflex LT instrument (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Leipzig, Germany) with FlexControl (version 3.0) software (Bruker Daltonics) as explained elsewhere (41).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), microscopy, and LCM.

Skin (n = 6) was snap-frozen in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek). For fluorescence microscopy, 5-μm-thick cryosections were obtained following the longitudinal sagittal place. For confocal microscopy, 70-μm-thick horizontal sections from the most apical part of the skin were obtained. All sections were stained with oligonucleotide probes EUB338 and NONEUB (control probe complementary to EUB338), labeled at their 5′ ends with indodicarbocyanine (Eurofins MWG Operon). EUB338 targets the 16S rRNA of ∼90% of all eubacteria (42). Details on oligonucleotide probes are available at probeBase. All SSC solutions were prepared from 20× SSC buffer (Sigma) (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). Hybridizations were performed at 37°C for 14 h with hybridization buffer (2× SSC–50% formamide) containing 1 μg/ml of the labeled probe. Slides were then washed with hybridization buffer without probes, followed by two more washes in washing buffer (0.1× SSC) and two washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 5 ng/ml) solution for 25 min at 37°C. Slides were mounted with fluorescent mounting media (KPL), and images were acquired and analyzed with a Nikon Ti fluorescence microscope and Elements Advanced Research software (version 4.0) or with a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope and Zen software. Confocal scans were performed dorsoventrally.

Additionally, skin cryosections from two different rainbow trout specimens were used for LCM using an ArcturusXT LCM microscope (Applied Biosystems). Skin cryoblocks were obtained using sterile dissection tools, and personnel used clean gloves at all times to avoid human skin contamination. The epithelium from six 5-μm-thick sections from each fish was captured and pooled into one sample for DNA purification. As a negative control, muscle underlying the dermis was also dissected. In order to prevent contamination at any step, the cryostat was disinfected, slides were autoclaved, and new clean blades handled with gloves were used for each individual sampled. The most superficial portion of the cryoblock was first trimmed with a separate blade prior to collection of sections that were used for LCM. Similar precautions were taken during microdissection of cryosections. Total DNA was extracted from the epithelial layer captured during LCM (including epithelial cells and goblet cells; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) or muscle cells using Arcturus PicoPure DNA isolation kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was subjected to the same PCR amplification and pryosequencing protocols as those described for the rest of the samples in this study. Muscle dissected samples failed to amplify by PCR (data not shown).

Statistical analysis.

Differences in alpha-diversity among body sites were tested by Kruskal-Wallis tests in IBM SPSS Statistics v.22. To test for significant differences in community composition among body sites, we used nonparametric multivariate analysis of variance (Adonis) and analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) in QIIME.

Accession numbers.

All data sets have been deposited at NCBI BioProject and are publicly available under BioProject ID number PRJNA248305. Nucleotide sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KR709316 to KR709320.

RESULTS

General aspects of rainbow trout bacterial communities characterized by 454 pyrosequencing.

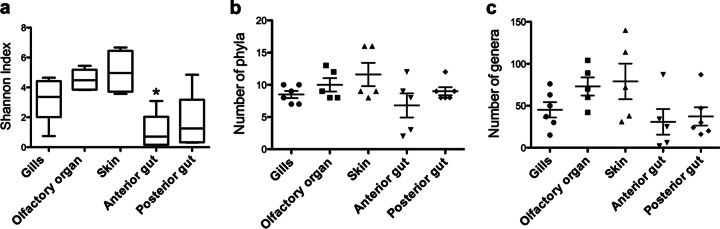

The number of reads obtained for each individual sample ranged between 1,665 reads and 14,135 reads, except for one skin sample that produced only 600 sequences. Thus, in order to normalize intersample variability, all analyses were performed using 1,600 sequences. This excluded the skin sample with 600 sequences. Shannon diversity differed significantly among body sites (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.006) (Fig. 2a). The anterior gut had a significantly lower diversity index than the rest of the body sites, the highest being the skin. Phylum richness analysis (number of unique phyla per individual sampling site at 1,600 sequences) revealed that the skin was the most diverse site, followed by the olfactory organ, gills, and both gut sites (Fig. 2b). Total numbers of unique phyla came from addition of all unique phyla discovered at the respective body site. Total numbers include all replicates. The gills, olfactory organ, skin, anterior gut, and posterior gut had totals of 14, 18, 17, 13, and 13 phyla, respectively (with a mean phylum richness of 10, 8.5, 10.5, 6.8, and 9, respectively). Analysis at the genus level showed a higher number of total genera present within the skin than at any other site (total, 199). The total number of genera found in each sample is presented in Fig. 2c. After the skin, the most diverse sites at the genus level were the olfactory organ, gills, posterior gut, and anterior gut (totals, 187, 140, 118, and 104, respectively). We report Good's coverage values ranging from 93.9% to 99.9%. The mean values for Good's coverage at the anterior gut, posterior gut, gills, olfactory organ, and skin were 98.4, 98.2, 97, 97.6, and 97.3%, respectively. Faith's phylogentic diversity (PD) mean values for anterior gut, posterior gut, gills, olfactory organ, and skin were 4.4, 6.0, 7.9, 10, and 10.4, respectively.

FIG 2.

Comparison of bacterial diversities present at rainbow trout mucosal body sites. (a) Shannon diversity index for each body site. Curves were calculated as a total from all individuals at each body site. The asterisk denotes statistically significant differences (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.006). (b) Total phyla present at each individual sampling site. Each dot represents an individual sample; horizontal lines represent average values. (c) Total genera present at each individual sampling site. Each dot represents an individual sample; horizontal lines represent average values.

Composition of the skin microbiome of rainbow trout.

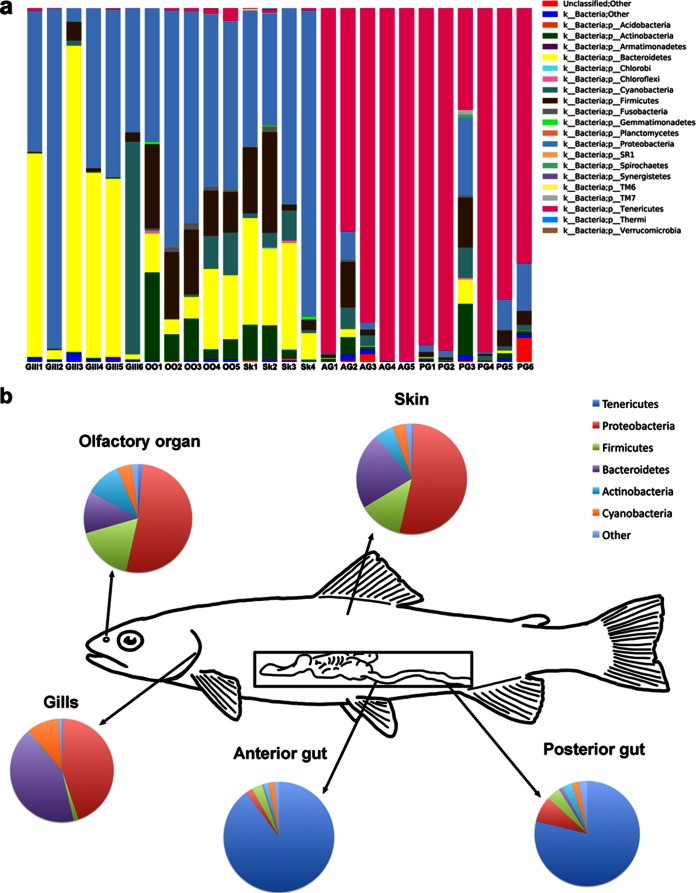

The skin microbiome contained the highest diversity at the genus level of bacterial communities of all sampled sites. A total number of 17 phyla were observed, with Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes being the most dominant phyla (Fig. 3). While the skin had one less phylum than the olfactory organ, the number of genera represented was the highest among all body sites, with 199 different genera. The mean number of OTUs observed was 152, with a maximum of 288 and a minimum of 46 OTUs. At the genus level, the bacterial community was consistently composed by Flectobacillus in the family Flexibacteriaceae, which accounted for 3.4 to 10.6% of the total bacterial community (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Flavobacteriaceae, Propionibacteriaceae, and Streptococcaceae accounted for 3.0 to 24.0%, 5.0 to 5.6%, and 2.8 to 16.0% of the sequences, respectively.

FIG 3.

Composition of the bacterial microbiomes of rainbow trout at different body sites. (a) Bar chart of the relative abundance of phyla present at each site and in each individual fish sampled. (b) Map of the bacterial microbiome of rainbow trout at each body site at the phylum level.

Composition of the gill microbiome of rainbow trout.

The gill microbiome was the third most diverse of the sites sampled in this study, with a total of 14 different phyla. Gills had a mean of 95 OTUs, with a maximum of 180 and a minimum of 39 OTUs. The gills showed the highest level of interindividual variability, as shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. The dominant phyla were Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria (Fig. 3). At the genus level, the diversity of the gill bacterial community was lower than that of the skin (see Fig. S2). The dominant genera included Flectobacillus., Flavobacterium, and the members of the Comamonadaceae family (see Fig. S2). Flectobacillus was present in all gill samples, although in one fish, it accounted for only 1.8% of all reads. In the rest of the samples, Flectobacillus contributed to 0.1 to 35.3% of all sequences. Flavobacterium, on the other hand, comprised between 7.7 and 61.7% of the bacterial community of the gills.

Composition of the olfactory organ microbiome of rainbow trout.

The bacterial community of the olfactory organ contained 18 total phyla (Fig. 3a), with the highest number of phyla present among all body sites. The mean OTU number was 133, the maximum 186, and the minimum 95. The community was dominated by Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes (Fig. 3). At the genus level, interindividual variability was present (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The class Betaproteobacteria (undetermined genus) accounted for 15.1 to 53.6% of all sequences. The genus Staphylococcus comprised 0.1 to 6.6% of the bacterial community (see Fig. S2). The family Streptococcaceae, in turn, was present at 0.1 to 7.8%.

Compositions of the anterior and posterior gut microbiomes of rainbow trout.

The anterior and posterior gut bacterial communities were similar to each other. In terms of total numbers of phyla, 13 phyla were observed in the anterior gut and 13 in the posterior gut (Fig. 2a). The mean number of OTUs in the anterior gut was 45 (maximum of 136 and minimum of 3), whereas in the posterior gut, the mean was 63 OTUs (maximum of 160 OTUs and minimum of 20). The anterior and posterior guts showed the lowest level of interindividual variability, as shown in the distance plot analysis (see Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). Considerable variability among individuals was present. Both gut sample sites were dominated by Tenericutes; Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria were also present. At the genus level, Mycoplasma dominated both the anterior and posterior gut samples (see Fig. S2).

Core microbiome analysis and comparisons across body sites.

An analysis of the core microbiome across body sites indicated that body sites have distinct communities with no shared OTUs down to 65% of samples (data not shown). Generally speaking, the core microbiotas among external sites (skin, olfactory organ and gills) were most similar and were distinct from the anterior and posterior gut samples. However, even after separating external from internal body sites, there were no shared OTUs at the conventional 90% of samples defined as the “core microbiota.” Thus, in the present study, rainbow trout did not have a core microbiota across body sites.

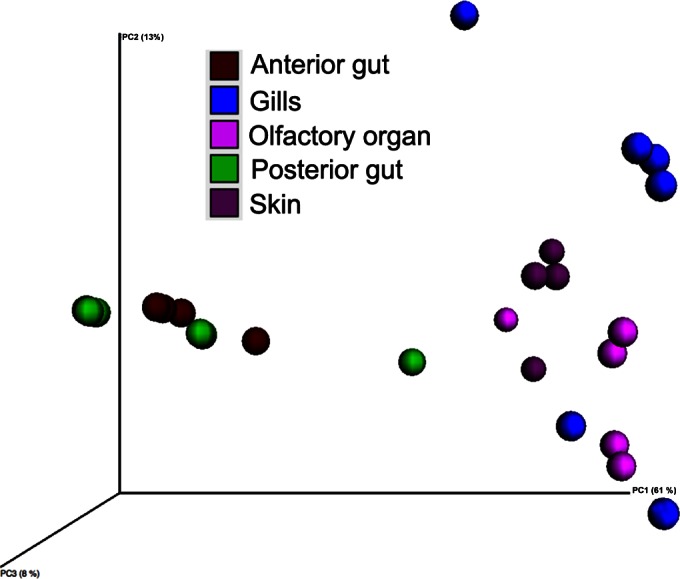

Principal coordinate analysis using the weighted UniFrac distance matrix (Fig. 4) indicates a clear separation between the microbial communities present at external and internal body sites. Internal sites were tightly clustered, while external sites were more loosely grouped, indicating some commonalities in community structure while still revealing unique groups present at each site. ANOSIM and Adonis analyses confirmed that body site is a significant predictor of variability in bacterial communities of rainbow trout, with both P values being less than 0.005 (0.001).

FIG 4.

Three-dimensional principal coordinate analysis plot, obtained with the weighted UniFrac distance matrix, comparing the bacterial communities present at each of the sampled body sites. Each dot represents an individual fish.

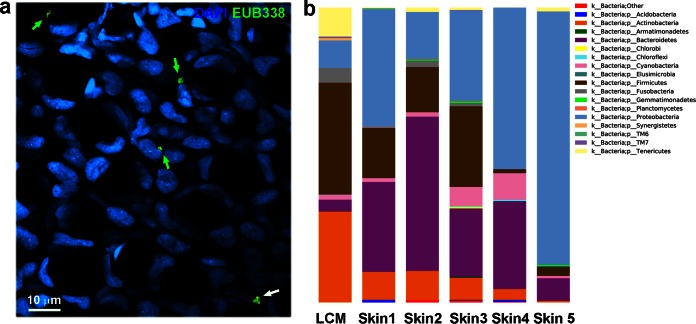

The rainbow trout skin possesses a rich intraepithelial microbiome.

16S rRNA FISH experiments revealed that bacteria reside within the epithelial layer of rainbow trout. Confocal microscopy studies show that bacteria were associated with both epithelial cells and goblet cells (Fig. 5a; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Bacteria could be observed both close to the apical portion of the epithelium and deep in the epithelium and sometimes the dermis (data not shown). Bacteria were often observed in microcolonies. Microscopy images were not enough to resolve the intracellular versus extracellular localization of the resident bacteria, although close localization to the cell nuclei is suggestive of at least some intracellular localization. Further experiments using LCM successfully amplified the 16S rRNA genes of the intraepithelial bacterial community. The composition of this community at the phylum level is shown in Fig. 5b and is compared to the total skin microbe-associated community. Strikingly, a total of 10 different phyla and 53 different genera were present inside the skin epithelium of two rainbow trout specimens (pooled samples). The intraepithelial community was enriched in two major groups: Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus, which accounted for 22.5% and 14.5% of the total intraepithelial diversity, respectively, compared to 5.6 to 6.8% and 3.0 to 3.5% in the total skin microbiota (mucus and epidermis combined).

FIG 5.

Rainbow trout skin has a diverse intraepithelial bacterial community. (a) Confocal microscopy image of a rainbow trout skin horizontal cryosection scanned dorsoventrally after staining with Cy5-EUB338 oligoprobe by FISH and scanned from above. Bacteria are shown in green. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (b) Bar chart of relative abundance of phyla present within the LCM sample and all skin samples. Skin 3 was included in this analysis with 600 sequences, and all skin samples as well as the LCM are rarefied to this measure. The total length of the bar is equivalent to 100%. OTUs matched at 97% identity to Greengenes August 2013 database.

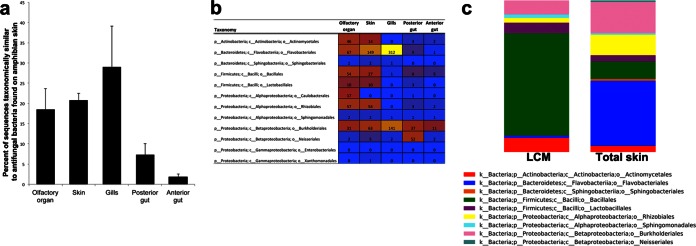

Comparison of trout-associated and amphibian-associated bacteria.

We found that 28.6% of the bacterial OTUs from trout are taxonomically similar (at least 97% rRNA sequence identity) to bacteria with antifungal properties that were cultured from amphibian skin (28). These bacterial OTUs from trout are taxonomically similar to OTUs from amphibian skin that were cultured and found to have antifungal properties. Proportions differed significantly among body sites (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.015). The gills, skin, and olfactory organ had higher proportions of bacteria that match with those found in amphibian skin than either the posterior or anterior gut (Fig. 6a).

FIG 6.

Comparison of trout-associated and amphibian-associated bacteria showing potential antifungal properties. (a) Trout bacteria that are taxonomically similar to those found on amphibian skin differ in abundance among trout body sites (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.015). Mean numbers of sequences and standard errors are displayed. (b) Heat map showing mean numbers of sequences from trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, in each taxonomic order of amphibian-associated antifungal bacteria found at each body site. Yellow indicates the highest abundance and blue the lowest. Red indicates intermediate abundance. (c) Comparison of taxonomically matching bacteria at the order level found in skin samples (n = 5) and by LCM of the epithelium (n = 1 pooled sample). The Bacillales group in the LCM sample is composed of 92% Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Compared to other body sites, gills host abundant Flavobacterium organisms and various Comamonadaceae and Oxalobacteraceae (Fig. 6b). The intraepithelial bacterial community also contained OTUs that matched with amphibian antifungal OTUs. Skin communities were dominated by Flavobacteriales, whereas Bacillales dominated the skin intraepithelial community (Fig. 6c). The range of OTUs that matched with amphibian skin antifungal OTUs was 10 to 35 in the skin, 14 by LCM. The proportion of antifungal sequences in total skin ranged from 16.2 to 23.7%, compared to 21.5% in the pooled LCM epithelium sample.

Fungal pathogen inhibition assays.

The ITS sequence obtained from the fungus isolate of trout skin showed 100% identity to Mucor hiemalis strain ZP-19 (GenBank accession number KR709320), and the fungus isolate from bullfrog eggs showed 100% identity to Saprolegnia australis voucher UEF-LIM6 (GenBank accession number KR709319).

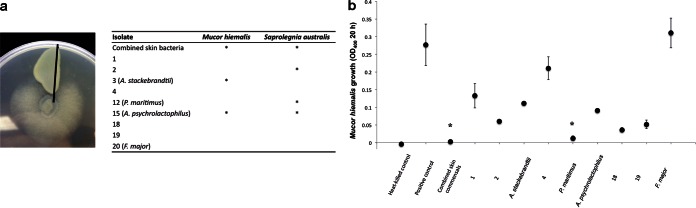

The two qualitative assays tested produced similar results, which are summarized in Fig. 7a. Two isolates, TSC3 and TSC15, produced cell-free supernatants that inhibited growth of Mucor hiemalis at 24 and 48 h. At later time points, the fungus overgrew the plates in all treatments. MALDI-TOF analysis revealed that both strains were Arthrobacter strains, and 16S rDNA sequencing found 100% identity with A. stackebrandtii and A. psychrolactophilus, respectively. Two isolates, TSC12 and TSC15, inhibited growth of S. australis in the qualitative coculture assays. Based on the 16S rDNA sequences, these strains matched (100% identity) to Psychrobacter maritimus and A. psychrolactophilus, respectively. The GenBank accession numbers of the identified A. stackebrandtii, P. maritimus, and A. psychrolactophilus sequences are KR709316, KR709318, and KR709317, respectively. Additionally, the combined skin aerobic bacterial sample inhibited growth of both M. hiemalis and S. australis.

FIG 7.

In vitro inhibition assays of Mucor hiemalis and Saprolegnia australis by different rainbow trout skin bacterial isolates. (a) Qualitative in vitro inhibition assays of M. hiemalis and S. australis by different rainbow trout skin bacterial isolates. (Left) Image of a qualitative inhibition assay showing inhibition of S. australis (center) by the trout combined skin bacterial sample in coculture. (Right) Summary table of all qualitative inhibition assay results. *, inhibition of the fungus growth was observed. (b) Quantitative inhibition assays of M. hiemalis 20 h after inoculation with rainbow trout commensal cell-free supernatants. *, no significant difference from heat-killed controls (independent t test, P > 0.05). The mean growth (optical density at 400 nm [OD400]) with standard error is shown for three replicates per bacterial isolate.

The quantitative inhibition assay performed with M. hiemalis revealed that most skin bacterial isolates produced cell-free supernatant capable of inhibiting growth M. hiemalis to some degree (Fig. 7b). In particular, complete growth inhibition was observed at 20 h caused by the combined skin bacteria and by P. maritimus (Fig. 7b).

DISCUSSION

Teleost fish mucosal surfaces are highly specialized to provide critical physiological functions, such as nutrient uptake in the gut or gas exchange in the gills. They also have complex microbial communities with many important biological roles. While the microbial communities present in the gut of teleost fish have been studied (18, 19, 20, 21, 43), those present at other major body sites remain for the most part uncharacterized. The present study represents an analysis of the microbiome of a teleost fish, the rainbow trout, across its main mucosal body sites.

Using 16S rRNA pyrosequencing, we revealed the presence of distinct bacterial communities across several teleost body sites. Body site is a key determinant of microbiota composition in other vertebrate species (14, 44). Importantly, the bacterial community of internal sites (anterior and posterior gut) was markedly different from that of the external sites sampled in this study, as in previous studies with other species (45). Differing tissue architecture and chemical properties can lead to differences in potential niche space for microbial communities to establish. The higher diversity observed in external sites may be a reflection of niche and environmental diversity, whereas the gut may offer more stable habitats that shape specialized microbial communities.

Out of all five sites sampled, the skin showed the highest bacterial diversity in rainbow trout. This community had a composition similar to that of other teleost species (46). We obtained a number of phyla comparable to that found in both amphibian and human skin communities (47). Interestingly, the most represented phylum was Proteobacteria, followed by Bacteroidetes. Recent studies with killifish (Fundulus grandis) (48), mosquito fish (Gambussia affinis) (49), and brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis) (50) used 16S rRNA pyrosequencing. Whereas whole fin clips were used for the first study, only skin mucus samples rather than whole skin tissue were sequenced in the second and third studies. In the killifish study, up to 10 different phyla were present, but the most abundant ones were Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria (48). Compared to the great diversity found in our study and the killifish study, only three phyla were found in the skin mucus of brook charr. Out of these three, two were very dominant and were the most dominant found in our study (Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes). Overall, the present study considerably increases our understanding of the complex microbial communities living in and on the skin. Additionally, our results underscore the idea that the skin microbiota of aquatic vertebrates is very different from the skin microbiota of terrestrial or semiterrestrial vertebrates. For instance, in humans the skin microbiota is mostly composed by Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, and in dogs Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes are the main bacterial groups, but amphibians are dominated by Betaproteobacteria, particularly the family Comamonadaceae (47, 51, 52). In aquatic larval amphibians and, interestingly, the humpback whale, a marine mammal, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes dominate the skin microbiome (53, 54). Previous studies had concluded that teleosts have low numbers (102 to 104/cm2) of bacteria associated with the skin, and in some cases, bacteria were not even observable using microscopy methods (55, 56). While the last may be true with regard to numbers of culturable bacteria, our results indicate that there is a very diverse microbiota living in association with the skin of rainbow trout.

As part of the topographical mapping effort of this study, we sampled anterior and posterior gut tissues from adult hatchery-reared rainbow trout. Our results show a lack of strong differences between the anterior and posterior guts. The main phylum present was Tenericutes, with Mycoplasma being the predominant genus. This bacterium was ubiquitous within all gut samples, comprising the majority of reads. The presence of large numbers of Tenericutes in the gut microbiome is in agreement with multiple studies with vertebrate animals, including studies of the porcine gut (57) and oyster gut (58). The distal gut microbiome of farmed and wild salmon is dominated by Mycoplasma as well (59). However, our results differ from previous studies with rainbow trout (18, 19, 21, 43), in which Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria represented the majority of phyla. However, these studies utilized primarily denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis and/or did not target the 16S rRNA region from V1 to V3 through pyrosequencing. Recently, the rainbow trout core gut microbiome under different diet and rearing conditions was analyzed using 16S rRNA (60). The diversity found in the former study differs from our findings, despite the fact that both used the region from V1 to V3. Studies performed with Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) showed a distinct shift in microbial community structure after starvation (61). While our fish were not starved beyond 48 h, removal of food from the gut, as well as absence of fecal contents in our gut samples, could contribute to certain bacteria being overrepresented and may explain the disagreement with other studies. Furthermore, differences in gut microbial composition may be due to differences between laboratory- and hatchery-reared fish. Moreover, the present study included a limited number of fish from one genetic stock that was sampled at one single time point, all of which are important factors that may account for the interstudy differences.

Thanks to the use of 16S rRNA pyrosequencing, we show here that the gill and nasal bacterial microbiomes are highly diverse (almost as much as the skin), yet they have unique bacterial compositions compared to those of other body sites. Based on culture methods, DGGE, and Sanger sequencing, teleost gills are mostly colonized by Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria (46). In our trout data set, however, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria were the most abundant bacterial groups. The recent discovery of a nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) in teleosts (62) and the presence of a rich bacterial microbiota in association with this mucosal surface highlights the importance of the cross talk between the nasal microbiota and vertebrate NALT.

Our initial pyrosequencing results and the finding that the skin is the most diverse site in trout led us to hypothesize that some of the diversity may be associated with bacterial colonization of the trout skin epidermis. FISH 16S staining revealed that bacteria in fact live within the skin epithelium of trout. Bacteria were observed within the epithelium and next to goblet cells. The different appendages and structures present in the skin of mammals provide unique habitats for the colonization of particular microbial species (14, 63). We found a strikingly diverse bacterial community living inside the epithelium, a finding that is in concordance with mammalian studies showing that skin commensals live deep in the dermal layers of the skin (64). In trout, this community was characterized by the phyla Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, particularly Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus, which were represented at higher proportions than in the total skin microbiome (mucus and epithelium). These phyla were also highly dominant in skin communities of the human microbiome (52). Interestingly, Propionibacterium colonizes various niches of the human body; particularly the sebaceous follicles of the skin, and Staphylococcus can live within human keratinocytes (65) and in deeper skin layers (66). Moreover, Staphylococcus warneri is a resident of the skin epidermis of rainbow trout (67). Thus, these two groups of bacteria are well known to exploit specific niches within the skin of vertebrates, likely due to the fact that they are facultative anaerobes. A possible explanation for the “permissive” properties of trout skin toward bacterial colonization involves bacterial compatibility to host cells. Teleost skin consists of living epithelial cells instead of keratinized dead cells present in terrestrial vertebrates. Thus, living cells may provide a more beneficial environment for microorganism colonization.

One of the benefits that vertebrates draw from establishing symbiosis with bacteria is the production of antimicrobial compounds that help them fight pathogens. The skin, gills, gut, and olfactory organ can all be portals of entry for disease agents. In this study, we identified two different Arthrobacter spp. (Arthrobacter stackebrandtii and A. psychrolactophilus) as well as P. maritimus as inhibitors of two different aquatic pathogenic fungi, S. australis and M. hiemalis, in vitro. Saprolegnia spp. are a threat for fish and amphibians worldwide (10), whereas Mucor spp. are also infective agents in teleost fish (68). Trout skin isolates A. psychrolactophilus and P. maritimus inhibited S. australis in our qualitative in vitro inhibition assays, whereas P. maritimus strongly inhibited the growth of M. hiemalis in the quantitative in vitro inhibition assay. Arthrobacter has been previously identified as a member of the fish microbiota (69, 70, 71). Additionally, Arthrobacter spp. are known to produce antibiotics (72). However, an Arthrobacter sp. isolated from Atlantic salmon eggs failed to reduce egg colonization by Saprolegnia (10). In the present study, only in vitro inhibition assays were performed, and therefore, our results cannot be extrapolated to in vivo settings. Alternatively, differences between studies may be due to the different bacterial species and origin of the fungal pathogen. On the other hand, Psychrobacter is known to be part of the normal skin and gut microbiotas of fish (71, 73). However, no previous reports have shown inhibition of fungal pathogens by Psychrobacter.

In conclusion, this study provides a detailed topographical map of the microbial communities that are present at the different mucosal sites of a nontetrapod aquatic vertebrate species, the rainbow trout. Importantly, we report the great bacterial diversity associated with the skin of teleosts and demonstrate that almost 50% of the skin microbial diversity is found within the epithelium itself. The present study also supports the idea that the bacterial communities associated with external fish surfaces (i.e., skin, gills, and olfactory organ) may contribute to the host array of antifungal defense mechanisms and may be applied to the control of emerging fungal diseases in wild and farmed fish.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Erin Larragoite for help with the LCM and 16S staining. We thank the CETI Molecular Biology Facility and Cristina Takacs-Vesbach for technical support with 454 pyrosequencing as well as Lisboa Spring Hatchery for the trout specimens. Jerri Bartholomew and Gregory Ruthig kindly donated the fungal isolates, and Patrick Kearns assisted with fungal molecular identification. We thank Trong Nguyen, Zhi Li, James Bauer, Molly Bletz, and Kelly Barnhart, and Mike Shiaris for assistance with fungal growth assays, Tricore Laboratories for MALDI-TOF analyses, and Victoria Hansen for assistance with artwork.

This work was funded by NIH COBRE grant P20GM103452.

We declare that we have no competing financial or nonfinancial interests.

L.L. performed DNA extractions, PCRs, denoising and QIIME analysis. D.C.W. conducted antifungal studies and bioinformatics and statistical analysis and developed the antifungal database. L.T. sequenced the fungal and bacterial isolates. I.S. sampled the fish, isolated skin strains, conducted microscopy and LCM experiments, designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01826-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cebra JJ. 1999. Influences of microbiota on intestinal immune system development. Am J Clin Nutr 69:1046S–1051S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sellon RK, Tonkonogy S, Schultz M, Dieleman LA, Grenther W, Balish E, Rennick DM, Sartor RB. 1998. Resident enteric bacteria are necessary for development of spontaneous colitis and immune system activation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun 66:5224–5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YK, Mazmanian SK. 2010. Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Science 330:1768–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1195568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McFall-Ngai M, Hadfield MG, Bosch TC, Carey HV, Domazet-Lošo T, Douglas AE, Dubilier N, Eberl G, Fukami T, Gilbert SF. 2013. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fierer N, Ladau J, Clemente JC, Leff JW, Owens SM, Pollard KS, Knight R, Gilbert JA, McCulley RL. 2013. Reconstructing the microbial diversity and function of pre-agricultural tallgrass prairie soils in the United States. Science 342:621–624. doi: 10.1126/science.1243768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schempp C, Emde M, Wölfle U. 2009. Dermatology in the Darwin anniversary. Part 1: evolution of the integument. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 7:750–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belkaid Y, Naik S. 2013. Compartmentalized and systemic control of tissue immunity by commensals. Nat Immunol 14:646–653. doi: 10.1038/ni.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. 2012. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature 489:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris RN, Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, Alford RA. 2009. Addition of antifungal skin bacteria to salamanders ameliorates the effects of chytridiomycosis. Dis Aquat Org 83:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, de Bruijn I, Jack AL, Drynan K, van den Berg AH, Thoen E, Sandoval-Sierra V, Skaar I, Van West P, Diéguez-Uribeondo J. 2014. Deciphering microbial landscapes of fish eggs to mitigate emerging diseases. ISME J 8:2002–2014. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrisko JE, Pearl CA, Pilliod DS, Sheridan PP, Williams CF, Peterson CR, Bury RB. 2008. Saprolegniaceae identified on amphibian eggs throughout the Pacific Northwest, U S A, by internal transcribed spacer sequences and phylogenetic analysis. Mycologia 100:171–180. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.100.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, Freeman CM, McCloskey L, Schmidt LA, Young VB, Toews GB, Curtis JL, Sundaram B. 2011. Analysis of the lung microbiome in the “healthy” smoker and in COPD. PLoS One 6:e16384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. 2007. The human microbiome project. Nature 449:804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Murray PR, Green ED. 2009. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koren O, Knights D, Gonzalez A, Waldron L, Segata N, Knight R, Huttenhower C, Ley RE. 2013. A guide to enterotypes across the human body: meta-analysis of microbial community structures in human microbiome datasets. PLoS Comput Biol 9:e1002863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salinas I, Zhang Y-A, Sunyer JO. 2011. Mucosal immunoglobulins and B cells of teleost fish. Dev Comp Immunol 35:1346–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Z, Parra D, Gómez D, Salinas I, Zhang Y-A, von Gersdorff Jørgensen L, Heinecke RD, Buchmann K, LaPatra S, Sunyer JO. 2013. Teleost skin, an ancient mucosal surface that elicits gut-like immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:13097–13102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304319110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai AR, Links MG, Collins SA, Mansfield GS, Drew MD, Van Kessel AG, Hill JE. 2012. Effects of plant-based diets on the distal gut microbiome of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 350:134–142. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez LM, Wong WR, Riener RM, Schulze CJ, Linington RG. 2012. Examining the fish microbiome: vertebrate-derived bacteria as an environmental niche for the discovery of unique marine natural products. PLoS One 7:e35398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rawls JF, Samuel BS, Gordon JI. 2004. Gnotobiotic zebrafish reveal evolutionarily conserved responses to the gut microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:4596–4601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400706101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarrete P, Magne F, Araneda C, Fuentes P, Barros L, Opazo R, Espejo R, Romero J. 2012. PCR-TTGE analysis of 16S rRNA from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) gut microbiota reveals host-specific communities of active bacteria. PLoS One 7:e31335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell KR, Takacs-Vesbach CD. 2008. A comparison of methods for total community DNA preservation and extraction from various thermal environments. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 35:1139–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0393-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar PS, Brooker MR, Dowd SE, Camerlengo T. 2011. Target region selection is a critical determinant of community fingerprints generated by 16S pyrosequencing. PLoS One 6:e20956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quince C, Lanzen A, Davenport RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. 2011. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics 12:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozupone C, Lladser ME, Knights D, Stombaugh J, Knight R. 2011. UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J 5:169. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodhams DC, Alford RA, Antwis RE, Archer H, Becker MH, Belden LK, Bell SC, Bletz M, Daskin JH, Davis LR. 2015. Antifungal isolates database of amphibian skin-associated bacteria and function against emerging fungal pathogens: Ecological Archives E096-059. Ecology 96:595. doi: 10.1890/14-1837.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belden LK, Harris RN. 2007. Infectious diseases in wildlife: the community ecology context. Front Ecol Environ 5:533–539. doi: 10.1890/060122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, André E, Duncan K, Harris RN. 2007. Common cutaneous bacteria from the eastern red-backed salamander can inhibit pathogenic fungi. J Infect 2007:630–640. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, Lam BA, Harris RN. 2008. Diversity of cutaneous bacteria with antifungal activity isolated from female four-toed salamanders. ISME J 2:145–157. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodhams DC, Hyatt AD, Boyle DG, Rollins-Smith LA. 2008. The northern leopard frog Rana pipiens is a widespread reservoir species harboring Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in North America. Herpetol Rev 39:66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam BA, Walke JB, Vredenburg VT, Harris RN. 2010. Proportion of individuals with anti-Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis skin bacteria is associated with population persistence in the frog Rana muscosa. Biol Conserv 143:529–531. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevenson LA, Alford RA, Bell SC, Roznik EA, Berger L, Pike DA. 2013. Variation in thermal performance of a widespread pathogen, the amphibian chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. PLoS One 8:e73830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flechas SV, Sarmiento C, Amézquita A. 2012. Bd on the beach: high prevalence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in the lowland forests of Gorgona Island (Colombia, South America) Ecohealth 9:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perna NT, Plunkett G, Burland V, Mau B, Glasner JD, Rose DJ, Mayhew GF, Evans PS, Gregor J, Kirkpatrick HA. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7. Nature 409:529–533. doi: 10.1038/35054089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruthig GR, Provost-Javier KN. 2012. Multihost saprobes are facultative pathogens of bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus eggs. Dis Aquat Organ 101:13–21. doi: 10.3354/dao02512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White T, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p 315–322. In Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (ed), PCR protocols. Academic Press Inc, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hulvey JP, Padgett DE, Bailey JC. 2007. Species boundaries within Saprolegnia (Saprolegniales, Oomycota) based on morphological and DNA sequence data. Mycologia 99:421–429. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.99.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tacchi L, Larragoite E, Salinas I. 2013. Discovery of J chain in African lungfish (Protopterus dolloi, Sarcopterygii) using high throughput transcriptome sequencing: implications in mucosal immunity. PLoS One 8:e70650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bizzini A, Durussel C, Bille J, Greub G, Prod'hom G. 2010. Performance of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of bacterial strains routinely isolated in a clinical microbiology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 48:1549–1554. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01794-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Devereux R, Stahl DA. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1919–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim DH, Brunt J, Austin B. 2007. Microbial diversity of intestinal contents and mucus in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J Appl Microbiol 102:1654–1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox MJ, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF. 2013. Sequencing the human microbiome in health and disease. Hum Mol Genet 22:R88–R94. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. 2009. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llewellyn MS, Boutin S, Hoseinifar SH, Derome N. 2014. Teleost microbiomes: the state of the art in their characterization, manipulation and importance in aquaculture and fisheries. Front Microbiol 5:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKenzie VJ, Bowers RM, Fierer N, Knight R, Lauber CL. 2012. Co-habiting amphibian species harbor unique skin bacterial communities in wild populations. ISME J 6:588–596. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larsen AM, Bullard SA, Womble M, Arias CR. 2015. Community structure of skin microbiome of gulf killifish, Fundulus grandis, is driven by seasonality and not exposure to oiled sediments in a Louisiana salt marsh. Microb Ecol 70:534–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leonard AB, Carlson JM, Bishoff DE, Sendelbach SI, Yung SB, Ramzanali S, Manage AB, Hyde ER, Petrosino JF, Primm TP. 2014. The skin microbiome of Gambusia affinis is defined and selective. Adv Microbiol 4:335–343. doi: 10.4236/aim.2014.47040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boutin S, Sauvage C, Bernatchez L, Audet C, Derome N. 2014. Inter individual variations of the fish skin microbiota: host genetics basis of mutualism? PLoS One 9:e102649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodrigues Hoffmann A, Patterson AP, Diesel A, Lawhon SD, Ly HJ, Stephenson CE, Mansell J, Steiner JM, Dowd SE, Olivry T. 2014. The skin microbiome in healthy and allergic dogs. PLoS One 9:e83197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Human Microbiome Project Consortium. 2012. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Apprill A, Robbins J, Eren AM, Pack AA, Reveillaud J, Mattila D, Moore M, Niemeyer M, Moore KM, Mincer TJ. 2014. Humpback whale populations share a core skin bacterial community: towards a health index for marine mammals? PLoS One 9:e90785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kueneman JG, Parfrey LW, Woodhams DC, Archer HM, Knight R, McKenzie VJ. 2014. The amphibian skin-associated microbiome across species, space and life history stages. Mol Ecol 23:1238–1250. doi: 10.1111/mec.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crouse-Eisnor R, Cone D, Odense P. 1985. Studies on relations of bacteria with skin surface of Carassius auratus L. and Poeciloia reticulata. J Fish Biol 27:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1985.tb03188.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Austin B. 2002. The bacterial microflora of fish. The ScientificWorldJournal 2:558–572. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2002.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leser TD, Amenuvor JZ, Jensen TK, Lindecrona RH, Boye M, Møller K. 2002. Culture-independent analysis of gut bacteria: the pig gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:673–690. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.673-690.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.King GM, Judd C, Kuske CR, Smith C. 2012. Analysis of stomach and gut microbiomes of the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) from coastal Louisiana, U S A. PLoS One 7:e51475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holben W, Williams P, Saarinen M, Särkilahti L, Apajalahti J. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of intestinal microflora indicates a novel Mycoplasma phylotype in farmed and wild salmon. Microb Ecol 44:175–185. doi: 10.1007/s00248-002-1011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong S, Waldrop T, Summerfelt S, Davidson J, Barrows F, Kenney PB, Welch T, Wiens GD, Snekvik K, Rawls JF. 2013. Aquacultured rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) possess a large core intestinal microbiota that is resistant to variation in diet and rearing density. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:4974–4984. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00924-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xia JH, Lin G, Fu GH, Wan ZY, Lee M, Wang L, Liu XJ, Yue GH. 2014. The intestinal microbiome of fish under starvation. BMC Genomics 15:266. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tacchi L, Musharrafieh R, Larragoite ET, Crossey K, Erhardt EB, Martin SA, LaPatra SE, Salinas I. 2014. Nasal immunity is an ancient arm of the mucosal immune system of vertebrates. Nat Commun 5:5205. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenthal M, Goldberg D, Aiello A, Larson E, Foxman B. 2011. Skin microbiota: microbial community structure and its potential association with health and disease. Infect Genet Evol 11:839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakatsuji T, Chiang H-I, Jiang SB, Nagarajan H, Zengler K, Gallo RL. 2013. The microbiome extends to subepidermal compartments of normal skin. Nat Commun 4:1431. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kintarak S, Whawell SA, Speight PM, Packer S, Nair SP. 2004. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by human keratinocytes. Infect Immun 72:5668–5675. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5668-5675.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakatsuji T, Gallo RL. 2014. Dermatological therapy by topical application of non-pathogenic bacteria. J Invest Dermatol 134:11–14. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Musharrafieh R, Tacchi L, Trujeque J, LaPatra S, Salinas I. 2014. Staphylococcus warneri, a resident skin commensal of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) with pathobiont characteristics. Vet Microbiol 169:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ke X, Wang J, Li M, Gu Z, Gong X. 2010. First report of Mucor circinelloides occurring on yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) from China. FEMS Microbiol Lett 302:144–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nayak SK. 2010. Role of gastrointestinal microbiota in fish. Aquac Res 41:1553–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2010.02546.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cantas L, Fraser TW, Fjelldal PG, Mayer I, Sørum H. 2011. The culturable intestinal microbiota of triploid and diploid juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)—a comparison of composition and drug resistance. BMC Vet Res 7:71. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ringø E, Sperstad S, Myklebust R, Refstie S, Krogdahl Å. 2006. Characterisation of the microbiota associated with intestine of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.): the effect of fish meal, standard soybean meal and a bioprocessed soybean meal. Aquaculture 261:829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wietz M, Månsson M, Bowman JS, Blom N, Ng Y, Gram L. 2012. Wide distribution of closely related, antibiotic-producing Arthrobacter strains throughout the Arctic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2039–2042. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07096-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bowman JP. 2006. The genus Psychrobacter, p 920–930. In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E (ed), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed, vol 3 Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.