Abstract

Background

According to a conceptual model described in this analysis, place of death is determined by an interplay of factors associated with the illness, the individual, and the environment.

Objectives

Our objective was to evaluate the determinants of place of death for adult patients who have been diagnosed with an advanced, life-limiting condition and are not expected to stabilize or improve.

Data Sources

A literature search was performed using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews, for studies published from January 1, 2004, to September 24, 2013.

Review Methods

Different places of death are considered in this analysis—home, nursing home, inpatient hospice, and inpatient palliative care unit, compared with hospital. We selected factors to evaluate from a list of possible predictors—i.e., determinants—of death. We extracted the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of each determinant, performed a meta-analysis if appropriate, and conducted a stratified analysis if substantial heterogeneity was observed.

Results

From a literature search yielding 5,899 citations, we included 2 systematic reviews and 29 observational studies. Factors that increased the likelihood of home death included multidisciplinary home palliative care, patient preference, having an informal caregiver, and the caregiver's ability to cope. Factors increasing the likelihood of a nursing home death included the availability of palliative care in the nursing home and the existence of advance directives. A cancer diagnosis and the involvement of home care services increased the likelihood of dying in an inpatient palliative care unit. A cancer diagnosis and a longer time between referral to palliative care and death increased the likelihood of inpatient hospice death. The quality of the evidence was considered low.

Limitations

Our results are based on those of retrospective observational studies.

Conclusions

The results obtained were consistent with previously published systematic reviews. The analysis identified several factors that are associated with place of death.

Plain Language Summary

Where a person will die depends on an interplay of factors that are known as “determinants of place of death.” This analysis set out to identify these determinants for adult patients who have been diagnosed with an advanced, life-limiting condition and are not expected to stabilize or improve. We searched the literature and found evidence that we deemed to be low quality, either because of limitations in the type of study that was done or in how the study was conducted. However, it is the best evidence available on the subject at the present time.

The evidence identified several determinants that increased the likelihood of a death at home. These included:

multidisciplinary palliative care that could be provided in the patient's home;

an early referral to palliative care (a month or more before death);

the patient's disease (for example, patients with cancer were more likely to die at home);

few or no hospitalizations during the end-of-life period;

living with someone, instead of alone;

the patient's preference for a home death;

family members’ preference for a home death;

the presence of an informal caregiver; and, especially, of one with a strong ability to cope.

Determinants that affected a patient's likelihood of dying in a nursing home, on the other hand, included the type of disease, and whether the patient preferred to die there. The type of disease was also a factor in a patient's likelihood of dying in an inpatient palliative care unit or an inpatient hospice. The availability of palliative care was a factor for each of the 4 places of death that were considered in this analysis. If palliative care could be provided in any of these places—at home, in a nursing home, in an inpatient palliative care unit, or in an inpatient hospice—this increased a patient's likelihood of dying there instead of in hospital. An earlier referral to palliative care (a month or more before death) also increased the likelihood of dying in an inpatient hospice instead of in hospital.

Background

In July 2013, the Evidence Development and Standards (EDS) branch of Health Quality Ontario (HQO) began work on developing an evidentiary framework for end of life care. The focus was on adults with advanced disease who are not expected to recover from their condition. This project emerged from a request by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care that HQO provide them with an evidentiary platform on strategies to optimize the care for patients with advanced disease, their caregivers (including family members), and providers.

After an initial review of research on end-of-life care, consultation with experts, and presentation to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC), the evidentiary framework was produced to focus on quality of care in both the inpatient and the outpatient (community) settings to reflect the reality that the best end-of-life care setting will differ with the circumstances and preferences of each client. HQO identified the following topics for analysis: determinants of place of death, patient care planning discussions, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, patient, informal caregiver and healthcare provider education, and team-based models of care. Evidence-based analyses were prepared for each of these topics.

HQO partnered with the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the selected interventions in Ontario populations. The economic models used administrative data to identify an end-of-life population and estimate costs and savings for interventions with significant estimates of effect. For more information on the economic analysis, please contact Murray Krahn at murray.krahn@theta.utoronto.ca.

The End-of-Life mega-analysis series is made up of the following reports, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ohtas-reports-and-ohtac-recommendations.

-

▸

End-of-Life Health Care in Ontario: OHTAC Recommendation

-

▸

Health Care for People Approaching the End of Life: An Evidentiary Framework

-

▸

Effect of Supportive Interventions on Informal Caregivers of People at the End of Life: A Rapid Review

-

▸

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Patients with Terminal Illness: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

The Determinants of Place of Death: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

Educational Intervention in End-of-Life Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

End-of-Life Care Interventions: An Economic Analysis

-

▸

Patient Care Planning Discussions for Patients at the End of Life: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

Team-Based Models for End-of-Life Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Objective of Analysis

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the determinants of place of death in adult patients who have been diagnosed with an advanced, life-limiting condition and are not expected to improve or stabilize.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Description of Disease/Condition

The palliative or end-of-life care population can be defined as those with a life-threatening disease who are not expected to stabilize or improve. (1) The needs of terminally ill patients vary; therefore certain places of death may be more appropriate for some patients than others. (2)

Between 87,000 and 89,000 people died in Ontario each year from 2007 to 2011. (3) According to Statistics Canada, in 2011, 64.7% of deaths in Canada and 59.3% in Ontario occurred in hospitals. (3) In 2009, the main cause of death was cancer (29.8%), followed by heart diseases (20.7%), and cerebrovascular diseases (5.9%). (4)

According to a conceptual model developed by Gomes and Higginson (5), place of death results from an interplay of factors that can be grouped into 3 domains: illness, individual, and environment. Individual-related factors include sociodemographic characteristics and patient's preferences with regards to place of death. (5) Environment-related factors can be divided into health care input (home care, hospital bed availability, and hospital admissions); social support (living arrangements, patient's social support network, and caregiver coping); and macrosocial factors (historical trends, health care policy, and cultural factors). (5)

Ontario Context

An Ontario study of 214 home care recipients and their caregivers, published in 2005, showed that 63% of patients and 88% of caregivers preferred a home death. (2) Thirty-two percent of patients and 23% of caregivers reported no preference for place of death. (2)

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question

What are the determinants of place of death in adult patients who have been diagnosed with an advanced, life-limiting condition and are not expected to stabilize or improve?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on September 24, 2013 using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews, for studies published from January 1, 2004, to September 24, 2013. (Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategy.) Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also be examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

including adult patients who have been diagnosed with an advanced, life-limiting condition and are not expected to stabilize or improve

published between January 1, 2004, and September 24, 2013

systematic reviews, health technology assessments, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and observational studies

where the evaluation of determinants of place of death was defined a priori

evaluating at least 1 of the determinants of place of death specified (below) under outcomes of interest

using multivariable analyses to adjust for potential confounders in the case of observational studies

Exclusion Criteria

studies that did not report the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for any of the determinants specified under outcomes of interest

studies including adults and children where results specific to adult patients could not be extracted or where the majority of the population comprised children

studies in which either of the 2 groups—control group, or the group under evaluation—included, within it, people who had died in different places, e.g., at home, in hospital, etc.

Outcomes of Interest

Place of death (dependent variable):

home

hospital

nursing home

inpatient hospice

inpatient palliative care unit

Determinants of place of death (independent variable):

type of disease

hospital admissions

functional status

pain

palliative care in the place of residence including home visits by physicians, nurses, or a multidisciplinary team

availability of hospital and nursing home beds

patient or family preference for place of death, including congruence between patient and family preference, if known

marital status or living arrangements

support for caregiver

caregiver's ability to care for patient

Statistical Analysis

The study design, patients’ baseline characteristics, and study results are presented in tables. The adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for each determinant, as presented in each study, were extracted. The odds ratios provided in the studies were inverted, if necessary, to ensure consistency of reporting.

Meta-analyses were performed if appropriate. Stratified analyses were performed for variables such as type of disease, setting, or country where the study was conducted, if deemed necessary to explain heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity was measured using the I2. Either a fixed or random effects model was used, depending on the degree of heterogeneity between studies. Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager. (6)

Quality of Evidence

The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) measurement tool was used to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. (7)

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. (8) The overall quality was determined to be high, moderate, low, or very low using a step-wise, structural methodology.

Study design was the first consideration; the starting assumption was that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are high quality, whereas observational studies are low quality. Five additional factors—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—were then taken into account. Any limitations in these areas resulted in downgrading the quality of evidence. Finally, 3 main factors that may raise the quality of evidence were considered: the large magnitude of effect, the dose response gradient, and any residual confounding factors. (8) For more detailed information, please refer to the latest series of GRADE articles. (8)

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the final quality score can be interpreted using the following definitions:

| High | High confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderate confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but may be substantially different |

| Low | Low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very Low | Very low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

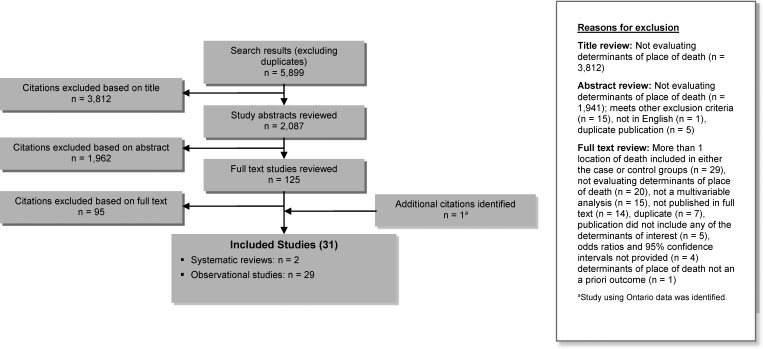

The database search yielded 5,899 citations published between January 1, 2004, and September 24, 2013, (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and abstract. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of when and for what reason citations were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart.

Abbreviation: n, number of studies.

Thirty studies (2 systematic reviews and 28 observational studies) met the inclusion criteria. An additional observational study was included because it provided information specific to Ontario patients. The reference lists of the included studies were hand-searched to identify other relevant studies but no additional publication was identified.

For each included study, the study design was identified and is summarized below in Table 1, a modified version of a hierarchy of study design by Goodman, 1996. (9)

Table 1:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|

| RCTs | |

| Systematic review of RCTs | |

| Large RCT | |

| Small RCT | |

| Observational Studies | |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with contemporaneous controls | 2 |

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | 29 |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with historical controls | |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | |

| Database, registry, or cross-sectional study | |

| Case series | |

| Retrospective review, modelling | |

| Studies presented at an international conference | |

| Expert opinion | |

| Total | 31 |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Determinants of Home Death

Two systematic reviews (5, 10) and 23 observational studies using multivariable analyses evaluated the determinants of home death. (2, 11–32) Hospital death was the most common comparator.

The 2006 systematic review by Gomes and Higginson (5) evaluated the determinants of home death in adult patients with cancer. Sixty-one observational studies were included in the review. (5) The authors identified strong evidence for 17 determinants of home death, the most important being low functional status, preference for home death, home care, intensity of home care, living with relatives, and extended family support. (5)

The systematic review by Howell et al compared the likelihood of home death for patients with solid versus non-solid tumours. The odds ratios reported in their meta-analysis, which included 17 observational studies, showed that patients with solid tumours were more likely to die at home (OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 2.07–2.44). (10)

Of the 23 observational studies included in our analysis that identified determinants of home death, 17 (74%) were retrospective cohort studies based on previously collected data from administrative databases or chart reviews (11–14, 17–19, 21, 23, 24, 26–32). The remaining studies were based on surveys whose data was provided by either the patient and/or a family member or by health care personnel.

The sample sizes ranged from 92 to 4,175 patients in the survey-based studies, and from 270 to 1,402,167 in the studies based on databases or chart reviews. In studies where patient non-participation was reported, the rate ranged from 8% to 49%.

The studies originated in various countries and/or regions: 3 in Canada (2, 28, 32); 9 in Asia (12, 15–17, 21–24, 31); 7 in Europe (11, 13, 14, 19, 26, 29, 30); 2 in the United States (25, 27); 1 in Mexico (20); and 1 in New Zealand. (18)

Eight studies (35%) were specific to cancer patients (11, 15, 16, 21–23, 26, 31) and 9 studies (39%) were restricted to patients receiving palliative home care. (2, 15–18, 22, 24, 31, 32) The remainder were not specific to a disease or setting. The majority of patients included in the studies were older than 65 years; the male/female breakdown was approximately 50/50. The rate of home death ranged from 20% to 66% (not provided in 4 studies). (2, 11, 12, 14–27, 29, 31) Five studies reported the patient and/or family preference for place of death. (2, 13, 15, 16, 22) Of those who stated a preference, 40% to 85% of patients preferred a home death, as did 42% to 65% of family members.

Additional details about study and patient characteristics are presented in Appendix 3.

All 23 studies adjusted for illness-related factors; all but 1 adjusted for sociodemographic factors; (24) and all but 2 adjusted for health care service availability factors. (21, 25) Additionally, 5 studies (19%) included patient and/or family preference for place of death in their multivariable model. (2, 13, 15, 16, 22) Eleven studies (48%) restricted the data collection to the last year of the patient's life. (2, 11, 13, 15, 18, 20, 23, 26, 28, 30, 32) The remainder did not specify the study time frame.

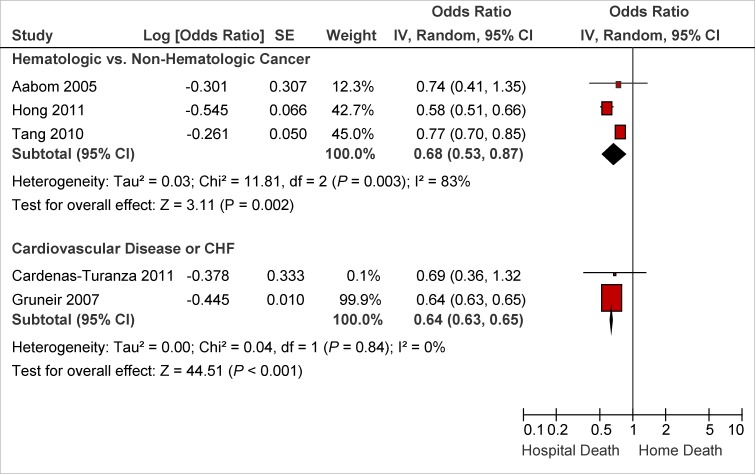

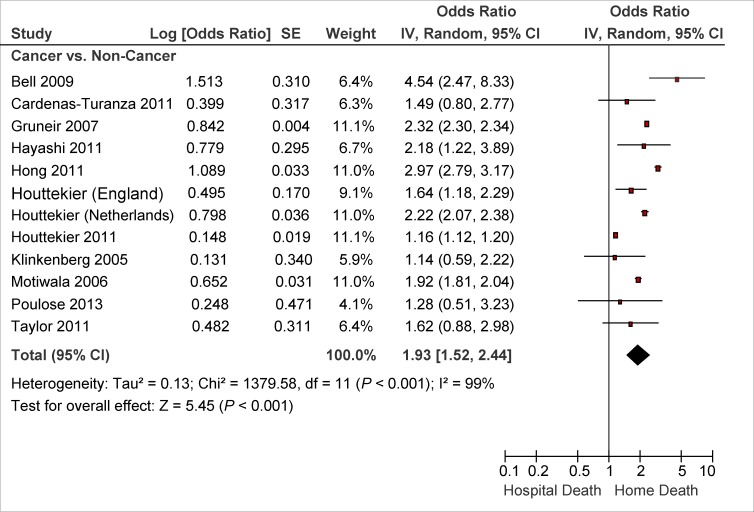

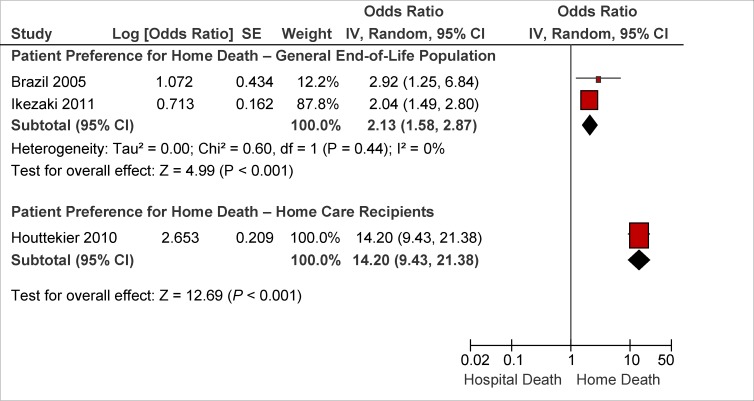

Table 2 summarizes the adjusted ORs of home versus hospital death, originating from multivariable analyses; we performed a meta-analyses if deemed appropriate. Factors that were associated with an increased likelihood of home death included nurse and physician home visits, multidisciplinary home palliative care, patient and family preference for home death, type of disease, not living alone, presence of an informal caregiver, and caregiver coping. On the other hand, factors that decreased the likelihood of home death included hospital admissions in the last year of life, admission to a hospital with palliative care services, and some diseases. Details about study results are provided in Appendix 3. The quality of the evidence was considered low to very low (see Appendix 2).

Table 2:

Determinants of Home Versus Hospital Death—Results of Observational Studies

| Determinant | Number of Studies | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | I2, if meta-analysis performed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse Home Visits | |||

| Nurse home visits to home care recipients (vs. no visits) | 1 study (24) | 3.13 (1.08–6.21) | N/A |

| Increase in nurse home visits to home care recipients (≥ 2–3/week vs. < 2–3/week) | 2 studies (15, 22) | 1.31 (0.87–1.98) | 0 |

| Nurse home visits to general end-of-life population (vs. no visits) | 1 study (11) | 2.78 (2.01–3.85) | N/A |

| Increase in nurse home visits to general end-of-life population | 1 study (26) | Reference: no visits 1–3 visits: 3.13 | N/A |

| 4–12 visits: 8.77a | |||

| > 12 visits: 14.20a | |||

| Family Physician Home Visits | |||

| Family physician home visits to home care recipients (vs. no visits) | 2 studies (2, 15) | 2.01 (1.30–3.12) | 57% |

| Increase in family physician home visits to home care recipients (≥ 2.6/week vs. < 2.6/week) | 1 study (22) | 2.70 (0.95–7.70) | N/A |

| Family physician home visits to general end-of-life population (vs. no visits) | 1 study (11) | 12.50 (9.37–16.68) | N/A |

| Rate of family physician home visits to general end-of-life population during the last 3 months of life | 1 study (11) | Reference: no visits 0.6–1 visit: 9.10 (5.90– 14.30) | N/A |

| 1–2 visits: 14.30 (1.0– 20.0) | |||

| 2–4 visits: 16.70 (12.80– 25.0) | |||

| > 4 visits: 20.0 (12.5– 33.30) | |||

| Home Care Teams | |||

| Multidisciplinary home care team (vs. usual care or no multidisciplinary home care team) | 2 studies (13, 32) | 2.56 (2.31–2.83) 8.40 (4.67–15.09) | N/A |

| In-Hospital Palliative Care | |||

| In-hospital palliative support team or hospice unit (yes vs. no) | 2 studies (13, 23) | 0.54 (0.33–0.89) | 18% |

| Preference for Home Death | |||

| Patient preference for home death vs. no patient preference for home death (general end-of-life population) | 2 studies (2, 16) | 2.13 (1.58–2.87) | 0 |

| Patient preference for home death vs. no patient preference for home death (home care recipients) | 1 study (2, 13, 16) | 14.20 (9.43–21.38) | N/A |

| Family preference for home death vs. no family preference for home death (non-cancer patients) | 1 study (16) | 11.51 (8.28–15.99) | N/A |

| Family preference for home death vs. no family preference for home death (cancer patients) | 1 study (16) | 20.07 (12.24–32.88) | N/A |

| Congruence between patient and family preference (non-cancer patients), vs. no preference congruence | 1 study (16) | 12.33 (9.50–16.00) | N/A |

| Congruence between patient and family preference (cancer patients), vs. no congruence | 1 study (16) | 57.00 (38.74–83.86) | N/A |

| Disease-Related | |||

| Cancer (vs. other diseases) | 11 studies (14, 17–21, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30) | 1.93 (1.52–2.44) | 99% |

| Hematological cancer (vs. non-hematological cancer) | 3 studies (11, 21, 23) | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 83% |

| Cardiovascular disease (vs. other diseases) | 2 studies (20, 27) | 0.64 (0.63–0.65) | 0 |

| Major acute condition (vs. other diseases) | 1 study (28) | 0.29 (0.26–0.33) | N/A |

| Timing of Referral to Palliative Care | |||

| Time from referral to palliative care to death (≥ 1 vs. < 1 month) | 1 study (17) | 2.21 (1.33–3.67) | N/A |

| Functional Status | |||

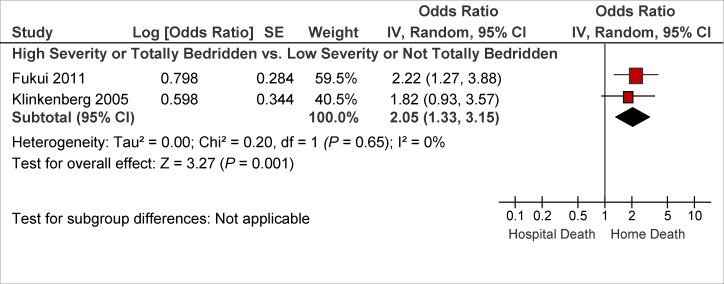

| Worse functional status or bedridden (vs. better functional status or not bedridden) | 2 studies (15, 30) | 2.05 (1.33–3.15) | 0 |

| Prior Hospital Admission | |||

| ICU admission in the last year of life (vs. no ICU admission) | 1 study (23) | 0.82 (0.81–0.83) | N/A |

| ≥ 1 hospital admission during the last year of life (vs. no admission) | 1 study (20) | 0.15 (0.07–0.30) | N/A |

| Decision not to re-hospitalize in the event of a crisis (vs. no) | 1 study (31) | 40.11 (11.81–136.26) | N/A |

| Informal Caregiver-Related | |||

| Informal caregiver satisfaction with support from family physician (vs. dissatisfaction) | 1 study (2) | 1.62 (0.30–8.62) | N/A |

| Low informal caregiver psychological distress during stable phase (vs. high distress) | 1 study (31) | 5.41 (1.13–25.92) | N/A |

| Informal caregiver health (excellent/very good vs. fair/poor) | 1 study (2) | 0.64 (0.21–1.99) | N/A |

| Informal care (often vs. none or sometimes) | 1 study (13) | 2.30 (1.15–4.60) | N/A |

| Hospital Bed Availability | |||

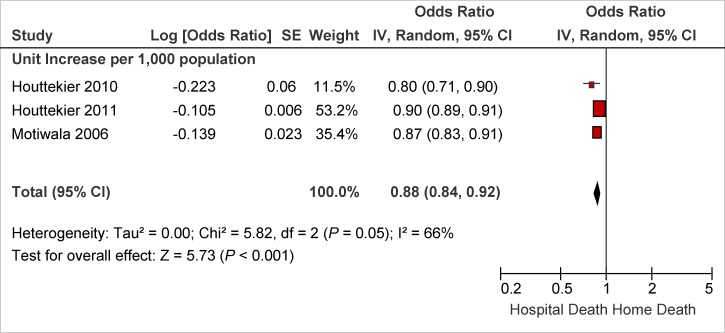

| Unit increase/1,000 population | 3 studies (13, 19, 28) | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 66% |

| ≥ 65 vs. < 65/10,000 population | 1 study (12) | 0.75 (0.74–0.76) | N/A |

| ≥ 6.75 vs. < 6.75/1,000 population | 1 study (29) | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | N/A |

| bed availability in 4th vs. 1st–3rd quarter | 1 study (23) | 0.79 (0.61–1.03) | N/A |

| Living Arrangements | |||

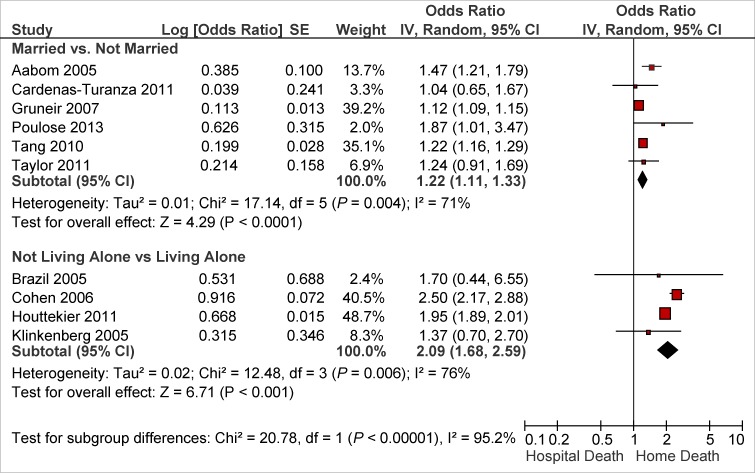

| Married (vs. not married) | 6 studies (11, 17, 18, 20, 23, 27) | 1.22 (1.11–1.33) | 71% |

| Not living alone (vs. living alone) | 4 studies (2, 19, 29, 30) | 2.09 (1.68–2.59) | 76% |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; N/A, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; vs., versus.

Statistically significant as per graph. P for trend not provided.

Determinants of Nursing Home Death

Ten observational studies evaluated the determinants of nursing home death. (13, 14, 19, 25, 28, 33–37) Hospital death was the most common comparator. These were retrospective cohort studies based on previously collected data from administrative databases or chart reviews. They originated in various countries and regions: 1 in Canada (28); 3 in Europe (13, 14, 19); 4 in the United States; (25, 34–36) and 2 in Japan. (16, 37) None of the studies were disease-specific; 5 (42%) were restricted to nursing home residents. (33–37)

The sample sizes ranged from 86 to 181,238 patients. The non-participation rate was low in the only 2 studies that provided such data: 1% (37) and 2% (28).

Most patients were older than 65 years of age and between 27% and 100% were male. The rate of nursing home death ranged from 47% to 87% in the studies restricted to nursing home residents (19, 33–37) and from 13% to 26% in the studies of general end-of-life population. (13, 14, 25, 28)

Additional details about study and patient characteristics are presented in Appendix 4.

All 10 studies adjusted for illness-related factors and health care services availability. Eight studies (80%) adjusted for socidemographic factors. (13, 14, 19, 25, 28, 35–37) Additionally, 5 studies (50%) included patient and/or family preference for place of death in their multivariable model. (13, 33–35, 37) Three studies (30%) restricted the data collection to the last year of the patient's life. (13, 28, 36) The remainder did not specify the study time frame.

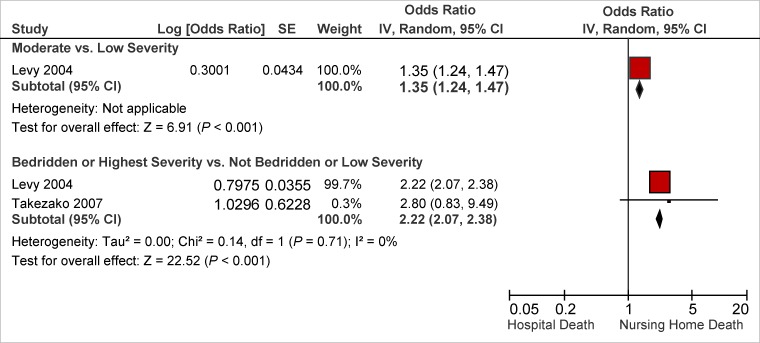

Table 3 summarizes the adjusted ORs of nursing home versus hospital death originating from multivariable analyses; meta-analyses using a random effects model were performed if deemed appropriate. Factors that were associated with an increased likelihood of nursing home death included palliative care services available in the nursing home, admission to a hospital-based nursing home, preference for nursing home death, having an advance directive completed, type of disease, functional status, a longer duration of stay at the nursing home, and nursing home bed availability. Details about the study results are provided in Appendix 4. The quality of the evidence was considered low to very low (see Appendix 2).

Table 3:

Determinants of Nursing Home vs. Hospital Death—Results of Observational Studies

| Determinant | Number of Studies | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | I2, if meta-analysis performed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-of-Life, Palliative or Hospice Care in the Nursing Home | ||||||

| End-of-Life care | 1 study (33) | 1.57 (1.14–2.16) | N/A | |||

| Hospice care | 2 studies (34, 36) | 15.16 (9.30–24.73) | 71% | |||

| Palliative care personnel | 1 study (13) | 9.40 (3.31–26.73) | N/A | |||

| Advance Directives | ||||||

| Any advance directive | 1 study (34) | 1.57 (1.35–1.82) | N/A | |||

| Do-not-resuscitate order | 1 study (35) | 3.33 (3.22–3.45) | N/A | |||

| Do-not-hospitalize order | 1 study (35) | 5.26 (4.71–5.88) | N/A | |||

| Preference for Nursing Home Death | ||||||

| Patient preference | 1 study (13) | 10.40 (4.40–24.90) | N/A | |||

| Family preference | 1 study (33) | 16.62 (11.38–24.27) | N/A | |||

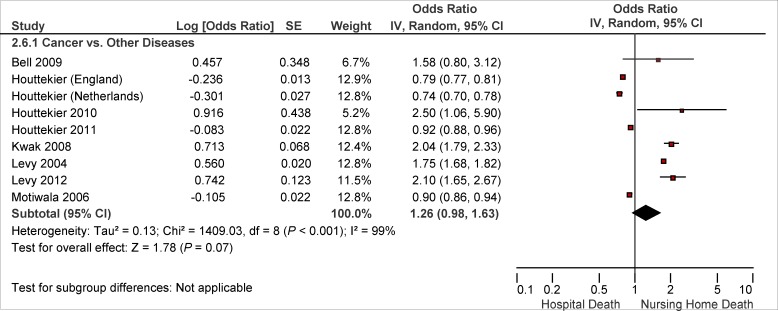

| Disease-Related | ||||||

| Cancer | 8 studies (1 study with 2 different estimates) (13, 14, 19, 25, 28, 34–36) | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | N/A | |||

| 0.79 (0.77–0.81) | ||||||

| 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | ||||||

| 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | ||||||

| 1.58 (0.80–3.12) | ||||||

| 1.75 (1.68–1.82) | ||||||

| 2.04 (1.79–2.33) | ||||||

| 2.10 (1.65–2.67) | ||||||

| 2.50 (1.06–5.90) | ||||||

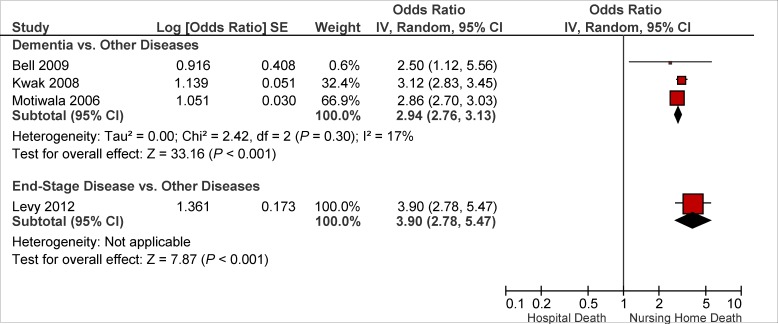

| End-stage disease | 1 study (34) | 3.90 (2.78–5.47) | N/A | |||

| Dementia | 3 studies (25, 28, 36) | 2.94 (2.76–3.13) | 17% | |||

| Stroke | 2 studies (25, 35) | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | N/A | |||

| 4.76 (2.49–9.09) | ||||||

| Heart Failure | 1 study (34) | 0.75 (0.64–0.88) | N/A | |||

| Diabetes | 2 studies (34, 35) | 0.70 (0.61–0.81) | N/A | |||

| 0.90 (0.87–0.93) | ||||||

| Functional Status | ||||||

| Worse functional status or bedridden (vs. better functional status or not bedridden) | 2 studies (35, 37) | 2.22 (2.07–2.38) | 0 | |||

| Nursing Home Characteristics | ||||||

| Hospital-based nursing home | 1 study (35) | 1.21 (1.15–1.25) | N/A | |||

| Full-time physician presence | 1 study (33) | 3.74 (1.03–13.63 | N/A | |||

| Nursing Home Bed Availability | ||||||

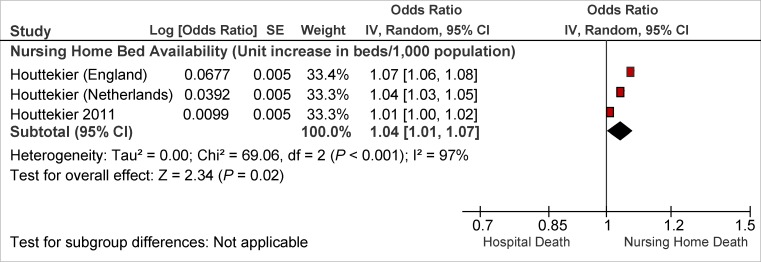

| Unit increase/1,000 population | 2 studies (14, 19) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 97% | |||

| Nursing Home Stay | ||||||

| 1-month increment | 1 study (34) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | N/A | |||

| ≥ 3 vs. < 3 months | 1 study (36) | 1.45 (1.39–1.52) | N/A | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N/A, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; vs., versus.

Determinants of Inpatient Palliative Care Unit Death

An observational study from Belgium evaluated the determinants of inpatient palliative care unit death compared with hospital death. (13) This retrospective cohort study was based on data from a national study on palliative care services in the last 3 months of life. (13) It included 577 patients; the non-participation rate was not reported. (13) Most patients were older than 65 years of age; half were male and half were female. (13) The study adjusted for sociodemographic, illness-related, and health care system-related factors. It found that a cancer diagnosis and home care involvement increased a patient's likelihood of dying in an inpatient palliative care unit (see Table 4). Additional details can be found in Appendix 5. The quality of the evidence was considered low (see Appendix 2).

Table 4:

Determinants of Inpatient Palliative Care Unit vs. Hospital Death—Results of Observational Studies

| Determinant | Number of Studies | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 1 study (13) | 6.50 (3.88–10.90) |

| Home care involvement in the last 3 months of life | 1 study (13) | 2.20 (1.38–3.50) |

| Multidisciplinary home care team involvement | 1 study (13) | 2.90 (1.53–5.50) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Determinants of Inpatient Hospice Death

Two observational studies from Singapore evaluated the determinants of inpatient hospice death versus hospital death. (17, 21) Both were retrospective cohort studies based on data from administrative databases. The studies had large sample sizes, 842 and 52,120, respectively. (17, 21) The non-participation rate, in the 1 study that reported it, was 11%. (17) Most patients were older than 65 years of age; half were male and half were female. Both studies adjusted for sociodemographic and illness-related factors and 1 study (17) was restricted to patients admitted to a hospital-based integrated palliative care service. The quality of the evidence was considered low. Additional details are provided in Appendix 6. The quality of the evidence was considered low (see Appendix 2).

Table 5:

Determinants of Inpatient Hospice vs. Hospital Death—Results of Observational Studies

| Determinant | Number of Studies | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 1 study (21) | 20.07 (16.05–25.09) |

| Time from referral to palliative care to death (≥ 1 vs. < 1 month) | 1 study (17) | 2.0 (1.13–3.60) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Limitations

Of the 29 observational studies identified, 23 (80%) were retrospective studies based mostly on data from administrative databases. The data originated in various countries and regions, which may have contributed to the considerable heterogeneity in some of the meta-analyses undertaken. However, despite this heterogeneity, the direction of the effect was consistent across the studies. We attempted to explain the cause of the heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses.

Two systematic reviews evaluating the determinants of home death, published in 2004 and 2010, also informed this analysis. However, these reviews were specific to cancer patients.

None of the 31 studies provided data on the effects of pain on place of death.

Conclusions

The results obtained were consistent with previously published systematic reviews.

Based on low quality evidence several factors were identified as determinants of place of death. Determinants that increased the likelihood of a death at home included:

interprofessional home end-of-life/palliative care

an earlier referral to end-of-life/palliative care services (a month or more before death)

type of underlying disease (for example, patients with cancer were more likely to die at home)

worse functional status

fewer hospitalizations during the last year of life

living arrangements such as living with someone

presence of an informal caregiver

informal caregiver coping

patient or family preference for a home death

Determinants that affected a patient's likelihood of dying in a nursing home included the type of disease, a worse functional status, the availability of palliative/end-of-life services in the nursing home, having completed an advance directive, a longer duration of stay in the nursing home, nursing home bed availability, and whether the patient preferred to die there. The type of disease was also a factor in a patient's likelihood of dying in an inpatient palliative care unit or an inpatient hospice.

The availability of palliative care was a factor for each of the 4 places of death that were considered in this analysis. If palliative care could be provided in any of these places—at home, in a nursing home, in an inpatient palliative care unit, or in an inpatient hospice—this increased a patient's likelihood of dying there instead of in hospital. On the other hand, the availability of end-of-life/palliative care in the hospital increased the likelihood of hospital compared to home death. An earlier referral to palliative care (a month or more before death) also increased the likelihood of dying in an inpatient hospice instead of in hospital.

The availability of resources to support the patient's physical and psychological needs in the place of residence during the end-of-life period also affects where a person may die.

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Sue MacLeod, BA

Medical Information Services

Corinne Holubowich, BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Health Quality Ontario's Expert Advisory Panel on End-of-Life Care

| Panel Member | Affiliation(s) | Appointment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Panel Co-Chairs | ||

| Dr Robert Fowler | Sunnybrook Research Institute University of Toronto | Senior Scientist Associate Professor |

| Shirlee Sharkey | St. Elizabeth Health Care Centre | President and CEO |

| Professional Organizations Representation | ||

| Dr Scott Wooder | Ontario Medical Association | President |

| Health Care System Representation | ||

| Dr Douglas Manuel | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute University of Ottawa | Senior Scientist Associate Professor |

| Primary/ Palliative Care | ||

| Dr Russell Goldman | Mount Sinai Hospital, Tammy Latner Centre for Palliative Care | Director |

| Dr Sandy Buchman | Mount Sinai Hospital, Tammy Latner Centre for Palliative Care Cancer Care Ontario University of Toronto | Educational Lead Clinical Lead QI Assistant Professor |

| Dr Mary Anne Huggins | Mississauga Halton Palliative Care Network; Dorothy Ley Hospice | Medical Director |

| Dr Cathy Faulds | London Family Health Team | Lead Physician |

| Dr José Pereira | The Ottawa Hospital University of Ottawa | Professor, and Chief of the Palliative Care program at The Ottawa Hospital |

| Dean Walters | Central East Community Care Access Centre | Nurse Practitioner |

| Critical Care | ||

| Dr Daren Heyland | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit Kingston General Hospital | Scientific Director |

| Oncology | ||

| Dr Craig Earle | Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Cancer Care Ontario | Director of Health Services Research Program |

| Internal Medicine | ||

| Dr John You | McMaster University | Associate Professor |

| Geriatrics | ||

| Dr Daphna Grossman | Baycrest Health Sciences | Deputy Head Palliative Care |

| Social Work | ||

| Mary-Lou Kelley | School of Social Work and Northern Ontario School of Medicine | Professor |

| Lakehead University | ||

| Emergency Medicine | ||

| Dr Barry McLellan | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | President and Chief Executive Officer |

| Bioethics | ||

| Robert Sibbald | London Health Sciences Centre University of Western Ontario | Professor |

| Nursing | ||

| Vicki Lejambe | Saint Elizabeth Health Care | Advanced Practice Consultant |

| Tracey DasGupta | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Director, Interprofessional Practice |

| Mary Jane Esplen | De Souza Institute University of Toronto | Director Clinician Scientist |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Search date: September 24, 2013

Databases searched: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process, Embase, All EBM Databases (see below), CINAHL

Limits: 2004-current; English

Filters: none

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to August 2013>, EBM Reviews -ACP Journal Club <1991 to September 2013>, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <3rd Quarter 2013>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <August 2013>, EBM Reviews -Cochrane Methodology Register <3rd Quarter 2012>, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment <3rd Quarter 2013>, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database <3rd Quarter 2013>, Embase <1980 to 2013 Week 38>, Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to September Week 2 2013>, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations <September 23, 2013>

Search Strategy:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Terminal Care/ | 85970 |

| 2 | exp Palliative Care/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 41033 |

| 3 | exp palliative therapy/ use emez | 60645 |

| 4 | exp Terminally Ill/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 5617 |

| 5 | exp terminally ill patient/ use emez | 5877 |

| 6 | exp terminal disease/ use emez | 4477 |

| 7 | exp dying/ use emez | 5616 |

| 8 | ((End adj2 life adj2 care) or EOL care or (terminal* adj2 (care or caring or ill* or disease*)) or palliat* or dying or (Advanced adj3 (disease* or illness*)) or end stage*).ti,ab. | 335051 |

| 9 | or/1–8 | 428351 |

| 10 | exp Hospices/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 4349 |

| 11 | exp hospice/ use emez | 6967 |

| 12 | exp Home Care Services/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 41659 |

| 13 | exp Home Care Agencies/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 1216 |

| 14 | exp home care/ use emez | 51971 |

| 15 | exp Hospitalization/ | 367600 |

| 16 | exp Long-Term Care/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 22720 |

| 17 | exp Nursing Homes/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 32849 |

| 18 | exp nursing home/ use emez | 37834 |

| 19 | exp Homes for the Aged/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 11419 |

| 20 | exp home for the aged/ use emez | 8622 |

| 21 | ((home or domicil* or communit*) adj2 (visit* or care or caring or caregiver* or health?care or assist* or aid* or agenc* or service* or rehabilitation)).ti,ab. | 105277 |

| 22 | (hospice* or hospital* or in?hospital or long term care facilit*).ti,ab. | 1938041 |

| 23 | or/10–22 | 2266328 |

| 24 | 9 and 23 | 70404 |

| 25 | (((place or location or site) adj2 death) or ((death or dying or die) adj2 (home* or nursing home* or hospice* or hospital*))).ti,ab. | 21749 |

| 26 | 24 or 25 | 88242 |

| 27 | exp Health Services Accessibility/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 85297 |

| 28 | exp Attitude to Death/ | 22572 |

| 29 | exp Decision Making/ | 258108 |

| 30 | exp Patient Satisfaction/ | 152037 |

| 31 | income/ | 58245 |

| 32 | (((determin* or factor* or indicator* or predict* or prefer*) adj2 (death or dying or die or palliative care* or terminal* ill*)) or (access* adj2 (health care or health service*))).ti,ab. | 41641 |

| 33 | ((determin* or factor* or indicator* or predict* or prefer* or influence*) adj4 (end of life or place of death)).ti,ab. | 1956 |

| 34 | or/27–33 | 597430 |

| 35 | 26 and 34 | 10309 |

| 36 | limit 35 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,ACP Journal Club,DARE,CCTR,CLCMR; records were retained] | 9427 |

| 37 | limit 36 to yr=“2004 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] | 5681 |

| 38 | remove duplicates from 37 | 3870 |

CINAHL

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Terminal Care+”) | 38,863 |

| S2 | (MH “Palliative Care”) | 19,643 |

| S3 | (MH “Terminally Ill Patients+”) | 7,655 |

| S4 | ((End N2 life N2 care) or EOL care or (terminal* N2 (care or caring or ill* or disease*)) or palliat* or dying or (advanced N3 (disease* or illness*)) or end stage*) | 52,080 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | 60,054 |

| S6 | (MH “Hospices”) | 2,462 |

| S7 | (MH “Home Health Care+”) | 32,531 |

| S8 | (MH “Home Health Agencies”) | 4,471 |

| S9 | (MH “Hospitalization+”) | 51,856 |

| S10 | (MH “Long Term Care”) | 18,249 |

| S11 | (MH “Nursing Homes+”) | 19,063 |

| S12 | ((home or domicil* or communit*) N2 (visit* or care or caring or caregiver* or health care or assist* or aid* or agenc* or service* or rehabilitation)) | 71,862 |

| S13 | (hospice* or hospital* or in?hospital or long term care facilit*) | 266,641 |

| S14 | S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 | 387,139 |

| S15 | S5 AND S14 | 19,811 |

| S16 | (((place or location or site) N2 death) or ((death or dying or die) N2 (home* or nursing home* or hospice* or hospital*))) | 3,092 |

| S17 | S15 OR S16 | 21,726 |

| S18 | (MH “Health Services Accessibility+”) | 47,527 |

| S19 | (MH “Attitude to Death+”) | 7,819 |

| S20 | (MH “Decision Making+”) | 62,594 |

| S21 | (MH “Patient Satisfaction”) | 30,524 |

| S22 | (MH “Income”) | 9,908 |

| S23 | (((determin* or factor* or indicator* or predict* or prefer*) N2 (death or dying or die or palliative care* or terminal* ill*)) or (access* N2 (health care or health service*))) | 57,923 |

| S24 | ((determin* or factor* or indicator* or predict* or prefer* or influence*) N4 (end of life or place of death)) | 913 |

| S25 | S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 | 162,112 |

| S26 | S17 AND S25 | 5,003 |

| S27 | S17 AND S25 Limiters - Published Date: 20040101–20131231; English Language | 3,295 |

Appendix 2: Evidence Quality Assessment

Table A1:

AMSTAR Scores of Included Systematic Reviews

| Author, Year | AMSTAR Scorea | (1) Provided Study Design | (2) Duplicate Study Selection | (3) Broad Literature Search | (4) Considered Status of Publication | (5) Listed Excluded Studies | (6) Provided Characteristics of Studies | (7) Assessed Scientific Quality | (8) Considered Quality in Report | (9) Methods to Combine Appropriate | (10) Assessed Publication Bias | (11) Stated Conflict of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gomes and Higginson, 2006 (5) | 8 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Howell et al, 2010 (10) | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

Maximum possible score is 11. Details of AMSTAR score are described in Shea et al. (7)

Regarding risk of bias, no serious risks were observed in the observational studies included. No limitations were identified in the eligibility criteria and no serious limitations were observed in the definition of the determinants of place of death or in the completeness of follow up. All observational studies performed multivariable analyses, adjusting for factors that had previously been identified as affecting place of death.

Table A2:

GRADE Evidence Profile for Included Observational Studies on the Determinants of Home Versus Hospital Death

| Number of Studies | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in nurse home visits in home care recipients (general end-of-life population) | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Nurse home visits in home care recipients | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Increase in nurse home visits (general end-of-life population) | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Nurse home visits (general end-of-life population) | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Increase in physician home visits in home care recipients | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Physician home visits in home care recipients | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Physician home visits (general end-of-life population) | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Increase in physician home visits (general end-of-life population) | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Multidisciplinary home care team | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| In-hospital palliative support team or hospice unit | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Patient preference for home death | |||||||

| 3 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Family preference for home death | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Congruence between patient and family preference | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Longer time from referral to palliative care to death | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Cancer | |||||||

| 12 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Hematological cancer | |||||||

| 3 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Major acute condition | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Functional status | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| ICU admissions in the last year of life | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Hospital admissions in the last year of life | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Decision not to hospitalize in the event of a crisis | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Informal caregiver satisfaction with support from family physician | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Serious limitationb | Undetected | ⊕ Very Low | |

| Informal caregiver psychological distress during stable phase | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Informal caregiver health | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Serious limitationb | Undetected | ⊕ Very Low | |

| Informal caregiver presence | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Hospital bed availability | |||||||

| 7 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| 10 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

Abbreviations: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; N/A, not applicable.

Substantial imprecision in the study results.

Table A3:

GRADE Evidence Profile for Included Observational Studies on the Determinants of Nursing Home Versus Hospital Death

| Number of Studies | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-of-life care in the nursing home | |||||||

| 4 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Preference for nursing home death | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Advance directives | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Cancer | |||||||

| 9 | No serious limitations | Serious limitationb | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕ Very Low (inconsistency) | |

| Dementia | |||||||

| 3 | No serious limitations | Serious limitationb | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| End-stage disease | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | Serious limitationb | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Stroke | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | Serious limitationb | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Functional status | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Family preference for home death | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | N/A | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Full-time physician presence in the nursing home | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Hospital-based nursing home | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Nursing home bed availability | |||||||

| 3 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Length of stay in nursing home | |||||||

| 2 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

Abbreviations: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; N/A, not applicable.

Substantial inconsistency across studies.

Table A4:

GRADE Evidence Profile for Included Observational Studies on the Determinants of Inpatient Palliative Care Unit Versus Hospital Death

| Number of Studies | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease type (cancer) | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Home or multidisciplinary care | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

Abbreviations: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

Table A5:

GRADE Evidence Profile for Included Observational Studies on the Determinants of Inpatient Hospice Versus Hospital Death

| Number of Studies | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease type | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

| Time from referral-to-death | |||||||

| 1 | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low | |

Abbreviations: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

Appendix 3: Studies Evaluating the Determinants of Home Death

Table A6:

Study Characteristics and Adjustment Factors—Included Observational Studies on Determinants of Home vs. Hospital Death

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Study Design Data Source Time Frame | Population | Sociodemographic Factors | Illness-Related Factors | Health Services Availability | Patient or Family Preference for Place of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Characteristics | Adjustment Factors | |||||

| Poulose et al, 2013 (17) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Singapore | ||||||

| N = 842 | ||||||

| Seow, 2013 (32) |

|

|

Not included | |||

| Canada | ||||||

| N = 6,218 | ||||||

| Houttekier et al, 2011 (19) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Belgium | ||||||

| N = 189,884 | ||||||

| Taylor et al, 2011 (18) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| New Zealand | ||||||

| N = 1,268 | ||||||

| Ikezaki et al, 2011 (16) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Japan | ||||||

| N = 4,175 | ||||||

| Fukui et al, 2011 (15) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Japan | N = 568 | |||||

| Hong et al, 2011 (21) |

|

|

|

|

Not included | Not included |

| Singapore | ||||||

| N = 52,120 | ||||||

| Cardenas-Turanza et al, 2011 (20) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Mexico | ||||||

| N = 473 | ||||||

| Hayashi et al, 2011 (24) |

|

|

Not included |

|

|

Not included |

| Japan | ||||||

| N = 99 | ||||||

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (13) |

|

|

|

|

||

| Belgium | ||||||

| N = 1,690 | ||||||

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (14) |

|

|

|

|

Not included | |

| Belgium – included in separate publication (19) | ||||||

| N = 56,341 (Netherlands) | ||||||

| N = 181,238 (England) | ||||||

| Nakamura et al, 2010 (22) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Japan | ||||||

| N = 92 | ||||||

| Tang et al, 2010 (23) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Taiwan | ||||||

| N = 201,252 | ||||||

| Bell et al, 2009 (25) |

|

|

|

Not included | Not included | |

| United States | ||||||

| N = 1,352 | ||||||

| Saugo et al, 2008 (26) |

|

|

|

|

Not included | |

| Italy | ||||||

| N = 350 | ||||||

| Lin et al, 2007 (12) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Taiwan | ||||||

| N = 697,814 | ||||||

| Gruneir et al, 2007 (27) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| United States | ||||||

| N = 1,402,167 | ||||||

| Motiwala et al, 2006 (28) |

|

|

|

|

Not included | |

| Canada | ||||||

| N = 58,689 | ||||||

| Cohen et al, 2006 (29) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Belgium | ||||||

| N = 55,759 | ||||||

| Klinkenberg et al, 2005 (30) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Netherlands | ||||||

| N = 270 | ||||||

| Brazil et al, 2005 (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Canada | ||||||

| N = 214 | ||||||

| Aabom et al, 2005 (11) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Denmark | ||||||

| N = 4,092 | ||||||

| Fukui et al, 2004 (31) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not included |

| Japan | ||||||

| N = 428 | ||||||

| Only using the variables not included in a more recent publication (15) | ||||||

Abbreviations: N, number of patients included.

Variables included in the multivariate model but ORs not provided.

Table A7:

Patient Characteristics in Included Observational Studies on the Determinants of Home Death

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Age (years) Sex | Setting | Type of Disease | Patient and Family Preference for Place of Death | Place of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poulose et al, 2013 (17) Singapore N = 842 |

• ≥ 65: 475 (56%) • Male: 405 (48%) |

• Hospital-based palliative care | • Cancer: 724 (86%) | Not available |

|

| Seow, 2013 (32) Canada N = 6218 |

• Median (IQR): 75: (64–84) • Male: 3,209 (50%) |

• Home care recipients | • Cancer: 4,950 (80%) | Not available | Not available |

| Taylor et al, 2011 (18) New Zealand N = 1,268 |

• ≥ 55: 1,108 (88%) • Male: 603 (48%) |

• General |

|

Not available |

|

| Houttekier et al, 2011 (19) Belgium 2007 data (N = 65,435) |

• ≥ 65: 54, 312 (83%) • Male: 32,522 (50%) |

• General |

|

Not available |

|

| Ikezaki et al 2011 (16) Japan N=1,664 Cancer |

• Mean: 76 ± 11 • Male: 993 (60%) |

• Home nursing care | • Cancer: 100% |

Patient (n = 1,017)

Family (n = 1,334)

|

|

| Ikezaki et al, 2011 (16) Japan N=2.511 Non-cancer |

• Mean: 84 ± 10 • Male: 1,199 (48%) |

• Home nursing care |

|

Patient (n = 988)

Family (n = 1,651)

|

|

| Cardenas-Turanza et al, 2011 (20) Mexico N = 473 |

• Mean (SD): 74 (73) • Male: 235 (50%) |

• General | Cause of death

|

Not available |

|

| Fukui et al, 2011 (15) Japan N = 568 |

• Mean (SD): 73 (12) • Male: 339 (60%) |

• Home palliative care | • Cancer: 100% |

Patient • Home: 385 (68%) Family • Home: 258 (45%) |

|

| Hong et al, 2011 (21) Singapore N = 52,120 |

|

• General | • Cancer: 100% | Not reported |

|

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (13) Belgium N = 1,690 |

• ≥ 65: 1,462 (88%) • Male: 839 (50%) |

• General |

|

Patient (n = 713)

|

Not available |

| Houttekier et al 2010 (14) Netherlands N = 56,341 |

• ≥ 70: 39,348 (70%) • Male: 29,635 (53%) |

• General | Cause of death

|

Not available |

|

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (14) England N = 181,238 |

• ≥ 70: 131,574 (73%) • Male: 90,619 (50%) |

• General | Cause of death

|

Not available |

|

| Nakamura et al, 2010 (22) Japan N = 92 |

• Mean (SD), years: 75 (10)a • Male: 47 (51%) |

• Home palliative care | • Cancer: 100% |

Patient

Family (n=88)

|

|

| Tang et al, 2010 (23) Taiwan N = 201,252 |

• ≥ 65: 119,690 (59%) • Male: 129,354 (64%) |

• General | • Cancer: 100% | Not available | • Home: 68,139 (34%) |

| Hayashi et al, 2011 (24) Japan N = 99 |

• Mean (SD): 78 (13) • Male: 49 (50%) |

• Recipients of home care services |

|

Not available |

|

| Bell et al, 2009 (25) US N = 1,352 |

• Mean: 84 • Male: 100% |

• General |

|

Not available |

|

| Saugo et al, 2008 (26) Italy N = 350 |

• ≥ 70: 225 (64%) • Male: 219 (63%) |

• General | • Cancer: 100% | Not available |

|

| Lin et al, 2007 (12) Taiwan N = 697,814 |

• ≥75: 423,552 (61%) • Male: 290,394 (42%) |

• General |

|

Not available |

|

| Gruneir et al, 2007 (27) US N = 1,402,167 |

• ≥ 75: 810,453 (58%) • Male: 671,638 (48%) |

• General |

|

Not available |

|

| Motiwala et al, 2006 (28) Canada N = 58,689 |

• ≥75: 43,071 (73%) • Male: 27,749 (47%) |

• General |

|

Not available | Not available |

| Cohen et al, 2006 (29) Belgium N = 55,759 |

• ≥65: 46,271 (83%) • Male: 28,248 (51%) |

• General |

|

Not available |

|

| Brazil et al, 2005 (2) Canada N = 214 |

• ≥50 yrs: 100% • Male: 142 (66%) |

• Home palliative care | • Cancer: 207 (96%) |

Patient

Family

|

|

| Klinkenberg et al, 2005 (30) Netherlands N = 270 |

• ≥ 80: 168 (62%) • Male: 167 (62%) |

• General |

|

Not available | Not available |

| Aabom et al, 2005 (11) Denmark N = 4,386 |

• ≥ 65: 2,979 (68%) • Male: 2,145 (49%) |

• General | • Cancer: 100% | Not available |

|

| Fukui et al, 2004 (31) Japan N = 428 |

• Mean (SD), years: 76 (11) • Male: 240 (56%) |

• Home care | • Cancer: 100% | Not available |

|

Abbreviations: CD, cardiovascular; IQR, inter-quartile range; N, number of patients included; SD, standard deviation.

Based on the group of patients who died at home.

Table A8:

Results From Included Observational Studies on Determinants of Home Versus Hospital Death—Disease-Related Variables

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Disease Type or Cause of Death OR (95% CI) | Functional Status | Hospital Admission OR (95% CI) | Time-to-Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poulose et al, 2013 (17) Singapore N = 842 |

Disease Type Reference: lung cancer Males • Non-cancer: 0.78 (0.31–1.96) |

Not available | Not available |

Referral-to-death interval Reference: < 30 days Male • ≥ 30 days: 2.21 (1.34–3.67) |

| Fukui et al, 2011 (15) Japan N = 568 |

Not available |

Reference: not bedridden • Totally bedridden: 2.22 (1.27–3.87) |

Not available | Not available |

| Hong et al, 2011 (21) Singapore N = 52,120 |

Cause of Death Reference: non-cancer • Cancer: 2.97 (2.79–3.17) Disease Type Reference: lung cancer • Hematological: 0.58 (0.51–0.66) |

Not available | Not available |

Diagnosis-to-death interval Reference: < 1 year

|

| Hayashi et al, 2011 (24) Japan N = 99 |

Disease Type Reference: non- cancer • Cancer: 2.18 (1.04–3.89) |

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Houttekier et al, 2011 (19) Belgium N = 189,884 |

Cause of Death Reference: non-cancer • Cancer: 1.16 (1.12–1.20) |

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Taylor et al, 2011 (18) New Zealand N = 1,268 |

Disease Type Reference: non-cancer • Cancer: 1.61 (0.88–2.94) |

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Cardenas-Turanza et al, 2011 (20) Mexico N = 10,561 |

Cause of death Reference: absence of disease

|

Not available |

Reference: no admission during last year of life • ≥ 1 admission: 0.15 (0.07–0.30) |

Not available |

| Houttekier et al (2010) (14) N = 56,341 (Netherlands) N = 181,238 (England) |

Disease Type Reference: non-cancer Netherlands • Cancer: 2.22 (2.07–2.38) England • Cancer: 1.64 (1.59–1.69) |

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Tang et al, 2010 (23) Taiwan N = 201,252 |

Disease Type Reference: lung cancer • Hematological: 0.77 (0.70–0.85) |

Not available |

ICU admission (last month of life) Reference: no admission • 0.82 (0.72–0.93) |

Diagnosis-to-death interval Reference: 1–2 months

|

| Bell et al, 2009 (25) US N = 1,352 |

Cause of death Reference: coronary heart disease

|

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Gruneir et al 2007 (27) US N = 1,402,167 |

Cause of death Reference: cancer

|

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Lin et al, 2007 (12) Taiwan N = 697,814 |

Cause of Death Reference unclear • Cancer: 0.70 (0.69–0.72) |

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Motiwala et al, 2006 (28) Canada N = 58,689 |

Disease Type Reference: absence of disease

|

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Cohen et al, 2006 (29) Belgium N = 55,759 |

Cause of Death Reference: acute LRTI

|

Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Klinkenberg et al, 2005 (30) Netherlands N = 186 |

Cause of death Reference: non-cancer • Cancer: 1.14 (0.59–2.22) |

Reference: higher functional status • Lower: 1.82 (0.93–3.57) |

Not available | Not available |

| Aabom et al, 2005 (11) Denmark N = 4,092 |

Disease Type Reference: non-hematological cancer • Hematological: 0.74 (0.40–1.35) |

Not available | Not available |

Diagnosis-to-death Reference: > 1 month • < 1 month: 0.44 (0.32–0.59) |

| Fukui et al, 2004 (31) Japan N = 428 |

Not available | Not available |

Re-hospitalization in the event of a crisis Reference.: re-hospitalization • 40.11 (11.81–136.26) |

Not available |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; N, number of patients included; OR, odds ratio.

Table A9:

Results From Included Observational Studies on Determinants of Home Versus Hospital Death—Health Care System-Related Variables

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Home Care Visits OR (95% CI) | Multidisciplinary Palliative Care Team in Hospital OR (95% CI) | Hospital Bed Availability OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seow, 2013 (32) Canada N = 6,218 |

Multidisciplinary home care team Reference: usual home care • 2.56 (2.31–2.83) |

Not available | Not available |

| Hayashi et al, 2011 (24) Japan N = 99 |

Home care nursing service Reference: no home care nursing service • 3.13 (1.08–6.21) |

Not available | Not available |

| Houttekier et al, 2011 (19) Belgium N = 189,884 |

Not available | Not available |

Reference: unit increase/1,000 population • 0.90 (0.88–0.91) |

| Fukui et al, 2011 (15) Japan N = 568 |

Primary physician 24-hour support Reference: no 24-hour primary physician support • 1.74 (1.08–2.80) Nurse visits 1st week after discharge Reference: < 3 visits • ≥ 3: 1.20 (0.77–1.88) |

Not available | Not available |

| Houttekier et al, 2010 Belgium (13) N = 750 |

Multidisciplinary home care team involvement Reference.: no multidisciplinary home care team involvement • 8.40 (4.70–15.10) |

In patients with ≥ 1 hospital admission in last 3 months • Yes: 0.34 (0.1–0.9) |

Reference: unit increase/1,000 population • 0.80 (0.60–0.90) |

| Nakamura et al, 2010 (22) Japan N = 92 |

Family physician visits Reference: < 2.6 times/week • ≥ 2.6: 2.70 (0.95–7.70) Nurse visits Reference: < 2.3 times/week • ≥ 2.3: 2.13 (0.74–6.12) |

Not available | Not available |

| Tang et al, 2010 (23) Taiwan N = 201,252 |

Not available |

Inpatient hospice unit availability Reference: no availability • 0.62 (0.40–0.96) |

Reference: < 1st quarter • > 3rd quarter: 0.79 (0.61–1.03) |

| Gruneir et al, 2007 (27) US N = 1,402,167 |

Not available | Not available |

Unit increase/1,000 population • 1.00 (0.99–1.00) |

| Cohen et al, 2006 (29) Belgium N = 55,759 |

Not available | Not available |

Reference: ≥ 6.75/1,000 population • < 6.75/1,000: 1.12 (1.05–1.20) |

| Brazil et al, 2005 (2) Canada N = 214 |

Family physician (last month before death) visits Reference: no visits • 4.42 (1.46–13.36) |

Not available | Not available |

| Aabom et al, 2005 (11) Danemark N = 4,092 |

Reference: no visits Family physician visits (last 3 months of life) • 12.50 (8.33–16.67) Visit rate

Community nurse visits (last 3 months of life) • 2.78 (2.08–3.85) |

Not available | Not available |

| Saugo et al, 2008 (26) Italy N = 350 |

Nurse visits (last 3 months of life) Reference: no visits |

Not available | Not available |

| Lin et al, 2007 (12) Taiwan N = 697,814 |

Not available | Not available |

Reference: ≤65/10,000 • > 65: 0.75 (0.74–0.76) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N, number of patients included; OR, odds ratio.

Statistically significant as per graph (CIs not provided).

Table A10:

Results From Included Observational Studies on Determinants of Home Versus Hospital Death—Living Arrangements and Informal Caregiver-Related Variables

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Marital Status Living Alone or Not Living Alone OR (95% CI) | Informal Caregiver Availability OR (95% CI) | Informal Caregiver Support and Coping OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poulose et al, 2013 (17) Singapore N = 842 |

Reference: not married Males • Married: 1.87 (1.01–3.47) Females • Married: 1.09 (0.68–1.73) |

Not available | Not available |

| Houttekier et al, 2011 (19) Belgium N = 189,884 |

Reference: living alone • Not living alone: 1.95 (1.89–2.01) |

Not available | Not available |

| Taylor et al, 2011 (18) New Zealand N = 1,269 |

Reference: not married • Married: 1.15 (0.68–1.95) |

Not available | Not available |

| Cardenas-Turanza et al, 2011 (20) Mexico N = 473 |

Reference: not married • Married: 1.04 (0.65–1.67) |

Not available | Not available |

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (13) Belgium N = 750 |

Not available |

Reference: none or sometimes • Often: 2.3 (1.2–4.6) |

Not available |

| Lin et al, 2007 (12) Taiwan N = 697,814 |

Reference: never married • Married: 6.42 (6.27–6.58) |

Not available | Not available |

| Tang et al, 2010 (23) Taiwan N = 201,252 |

Reference: single • Married: 1.22 (1.15–1.29) |

Not available | Not available |

| Cohen et al, 2006 (29) Belgium N = 55,759 |

Reference: living alone • Not alone: 1.29 (1.18–1.41) |

Not available | Not available |

| Brazil et al, 2005 (2) Canada N = 214 |

Reference: not living with caregiver • Living with caregiver: 1.70 (0.44–6.55) |

Not available |

Satisfaction with support from family physician Reference: dissatisfied • Satisfied: 1.62 (0.31–8.62) Caregiver health Reference: fair/poor • Excellent/very good: 0.64 (0.20–1.99) |

| Klinkenberg et al, 2005 (30) Netherlands N = 209 |

Reference: no partner • Partner: 1.37 (0.70–2.70) |

Not available | Not available |

| Aabom et al, 2005 (11) Denmark N = 4,092 |

Reference: not married • Married: 1.47 (1.18–1.79) |

Not available | Not available |

| Fukui et al, 2004 (31) Japan N = 428 |

Not available | Not available |

Psychological distress during stable phase Reference: high • Low: 5.41 (1.13–25.92) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N, number of patients included; OR, odds ratio.

Table A11:

Results From Included Observational Studies on Determinants of Home Versus Hospital Death—Patient and Family Preferences

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Patient Preference OR (95% CI) | Family Preference OR (95% CI) | Congruence of Patient and Family Preference OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ikezaki et al, 2011 (16) Japan N = 4,175 |

Reference: no preference for home death Cancer Patients • Only patient prefers home: 4.69 (3.11–7.07) Non-Cancer Patients • Only patient prefers home: 2.04 (1.48–2.80) |

Reference: no preference for home death Cancer Patients • Only family prefers home: 20.07 (12.24–32.91) Non-Cancer Patients • Only family prefers home: 11.51 (8.56–15.99) |

Reference: no congruence for home death Cancer Patients • Congruence: 57.00 (38.79–83.76) Non-Cancer Patients Congruence: 12.33 (9.51–15.99) |

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (13) Belgium N = 1,283 |

Reference: unknown or not home • Home: 14.20 (9.50–21.40) |

Not available | Not available |

| Brazil et al, 2005 (2) Canada N = 214 |

Reference: no stated preference • Preference for home death: 2.92 (1.25–6.84) |

Not available | Not available |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N, number of patients included; OR, odds ratio.

Figure A1: Forest Plot of the Association Between Functional Status and Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Figure A2: Forest Plot of the Association Between Hospital Bed Availability and Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Figure A3: Forest Plot of the Association Between Living Arrangements and Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Figure A4: Forest Plot of the Association Between Disease Type and Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Figure A5: Forest Plot of the Association Between Cancer and Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Figure A6: Forest Plot of the Association Between Patient Preference for Home Death and Home Death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Appendix 4: Studies Evaluating the Determinants of Nursing Home Death

Table A12:

Study Characteristics and Adjustment Factors—Included Observational Studies on the Determinants of Nursing Home Versus Hospital Death

| Author, Year Country Sample Size | Study Design Data Source Time Frame | Population | Sociodemographic Factors | Illness-Related Factors | Health Services Availability | Patient or Family Preference for Place of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Characteristics | Adjustment Factors | |||||

| Ikegami et al, 2012 (33) Japan N = 1,160 |

|

• Nursing home residents | • Not included | • Cause of death |

|

|

| Levy et al, 2012 (34) United States N = 7,408 |

|

|

• Not included |

|

|

• Advance directives |

| Houttekier et al, 2011 (19) Belgium N = 79,846 |

|

|

|

• Cause of death | • Bed availability in hospital and care homes | • Not included |

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (14) Results for Belgium included in separate publication (19) N = 56,341 (Netherlands) N = 181,238 (England) |

|

|

• Disease type |

|

• Not included | |

| Houttekier et al, 2010 (13) Belgium N = 1,690 |

|

|

• Cause of deatha | • Patient preference | ||

| Bell et al, 2009 (25) United States N = 1,352 |

|

|

|

• Not included | • Not included | |

| Kwak et al, 2008 (36) United States N = 30,765 |

|

|

|

|

|

• Not included |

| Takezako et al, 2007 (37) Japan N = 86 |

|

|

|

• Functional status |

|

• Family preference for nursing home care |

| Motiwala, et al 2006 (28) Canada N = 58,689 |

|