Abstract

Reovirus is a naturally occurring oncolytic virus currently in early clinical trials. However, the rapid induction of neutralizing antibodies represents a major obstacle to successful systemic delivery. This study addresses, for the first time, the ability of cellular carriers in the form of T cells and dendritic cells (DC) to protect reovirus from systemic neutralization. In addition, the ability of these cellular carriers to manipulate the subsequent balance of anti-viral versus anti-tumour immune response is explored. Reovirus, either neat or loaded onto DC or T cells, was delivered intravenously into reovirus-naive or reovirus-immune C57Bl/6 mice bearing lymph node B16tk melanoma metastases. Three and 10 days after treatment, reovirus delivery, carrier cell trafficking, metastatic clearance and priming of anti-tumour/anti-viral immunity were assessed. In naive mice, reovirus delivered either neat or through cell carriage was detectable in the tumour-draining lymph nodes 3 days after treatment, though complete clearance of metastases was only obtained when the virus was delivered on T cells or mature DC (mDC); neat reovirus or loaded immature DC (iDC) gave only partial early tumour clearance. Furthermore, only T cells carrying reovirus generated anti-tumour immune responses and long-term tumour clearance; reovirus-loaded DC, in contrast, generated only an anti-viral immune response. In reovirus-immune mice, however, the results were different. Neat reovirus was completely ineffective as a therapy, whereas mDC—though not iDC—as well as T cells, effectively delivered reovirus to melanoma in vivo for therapy and anti-tumour immune priming. Moreover, mDC were more effective than T cells over a range of viral loads. These data show that systemically administered neat reovirus is not optimal for therapy, and that DC may be an appropriate vehicle for carriage of significant levels of reovirus to tumours. The pre-existing immune status against the virus is critical in determining the balance between anti-viral and anti-tumour immunity elicited when reovirus is delivered by cell carriage, and the viral dose and mode of delivery, as well as the immune status of patients, may profoundly affect the success of any clinical anti-tumour viral therapy. These findings are therefore of direct translational relevance for the future design of clinical trials.

Keywords: tumour immunity, dendritic cells, reovirus, cell carriers

Introduction

Oncolytic viruses are self-replicating, tumour selective and directly lyse cancer cells. Clinical trials with several of these agents have been completed, with some evidence of efficacy.1 The majority of studies have administered the oncolytic virus by intratumoural injection to maximize tumour delivery.2 However, effective systemic viral delivery to metastatic disease or inaccessible tumour sites is required to fulfil the potential of these promising novel therapeutic agents.

A series of non-specific and specific host defences remove virus particles from the circulation, representing a major obstacle to achieving effective systemic delivery. Non-specific mechanisms include adherence of virus particles to non-blood cells,3 binding to red blood cells,4 uptake by the reticulo-endothelial system5,6 and neutralization by the alternative complement pathway.7,8 Preimmune IgM, and high affinity virus-specific antibody (Ab) interactions are additional barriers. Neutralizing Ab binds to the surface of viral particles, preventing viral binding to cellular receptors required for cell infection.9,10 Non-neutralizing Ab binds to viral particles, fixing the complement pathway.11

Several widely differing approaches aimed at protecting viral particles within the circulation and ensuring tumour delivery are currently the focus of intense research activity. These include modification of the viral coat, including lipid encapsulation and polymer coating,12,13 although application of these technologies to viruses is technically challenging.11 Other approaches include serotype switching to evade specific Ab neutralization,14 and bispecific fusion proteins.15

The use of cell carriers to chaperone viral particles within the circulation is a promising approach to systemic delivery, potentially applicable to all oncolytic viruses. Pre-clinical studies have shown that various carrier cells, including T cells,16 monocytes, endothelial cells17 and tumour cells (autologous, allo- or xenogeneic),18 can prevent systemic viral elimination. Carrier cells may simply deliver their payload to the target tumour (‘hitchhiking’), or the virus may actively replicate within the carrier cell, making it a ‘trojan horse’ for amplified viral delivery. Cell carriers with inherent tumour-trafficking properties are advantageous in enhancing viral delivery, and cells of the immune system have been used for this purpose.19 An attractive strategy is the use of cell carriers which are themselves biologically active against the tumour, such as antigenspecific T cells20 or cytokine-induced killer cells,21 forming synergistic combinations with viruses.

There is increasing evidence that innate and adaptive immune responses play a major role in mediating the efficacy of oncolytic virotherapy, and that overcoming the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment may be critical to their efficacy.22 Dendritic cells (DC) are the prime antigen-presenting cells coordinating adaptive immune responses, and have been administered in many clinical studies; however, they have not been previously tested as cellular carriers of oncolytic viruses. The use of DC to carry viruses offers the possibility of combining delivery with immune manipulation; tumour material released following viral oncolysis may be taken up and presented to immune cells by the delivery of DC. The balance of anti-viral and anti-tumour immune responses is, however, critical: virally loaded DC may efficiently induce anti-viral immunity, leading to rapid viral clearance.

Reovirus is a naturally occurring, non-pathogenic, oncolytic double-stranded RNA virus, currently in a range of phase I and II clinical trials.23 Transformed cells with activated ras-signalling pathways are susceptible to reovirus.24 Neutralizing antibodies, however, represent a major obstacle to successful systemic delivery. Most adults have pre-existing anti-reovirus antibodies following prior subclinical exposure,25 and Ab titres have been found to rise rapidly by a median of 250-fold in a phase I study of i.v. reovirus therapy.26 This study is the first to test the ability of cell carriers to protect reovirus particles from systemic neutralization and to deliver the virus to tumour sites. We have previously demonstrated the ability of reovirus to activate innate27 and adaptive anti-tumour immune responses.28 In addition to T-cell delivery, here we have also tested the immunological consequences of DC-mediated delivery of this virus.

In a murine model of melanoma lymph node metastasis, non-antigen-specific T cells were effective at delivering vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) in vivo, and purging the lymph nodes of a tumour, with concomitant priming of anti-tumour immunity.16 The same system was used here to deliver reovirus systemically in vivo loaded on T cells or DC. Both DC and T cells effectively delivered reovirus to lymph node metastases for potential therapy and anti-tumour immune priming. Both cell types were able to protect reovirus from systemic neutralization, although DC were more efficient at higher viral loads. In naive mice, immature DC (iDC) and mDC instigated a significant anti-viral response, preventing the longer term immune-mediated tumour control seen with T-cell carriers. In contrast, in the more challenging and relevant delivery model of reovirus-immune mice, cell and virus delivery was much lower and only T cells loaded at a low MOI and mDC at low or high MOI, were able to purge the tumour. Both T cells and DC therefore appear to be appropriate vehicles for viral carriage, whereas the anti-viral immune status is critical to determining the balance of the anti-viral/anti-tumour immunity elicited.

Results

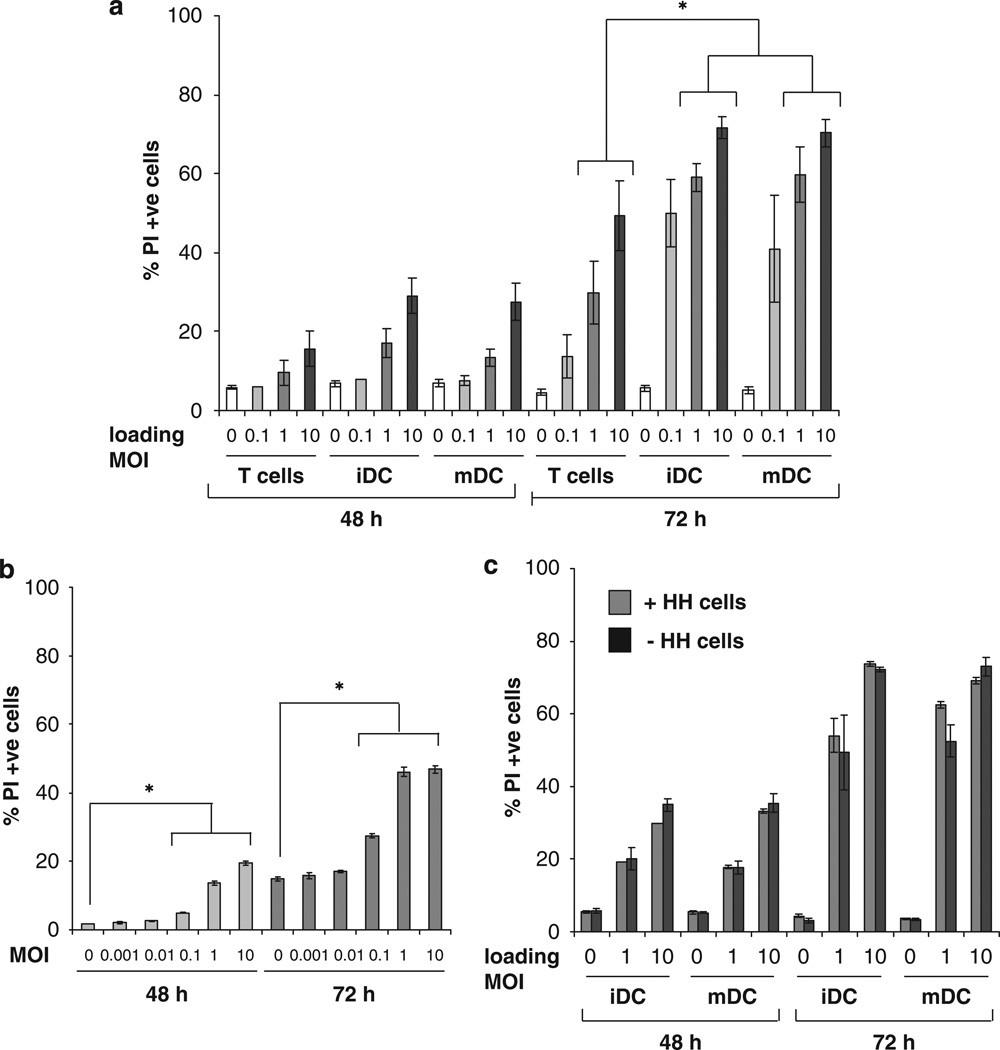

DC and T cells deliver reovirus for melanoma killing in vitro

Although retrovirus and VSV hitchhiking on T cells has already been described,16,29 reovirus, which targets melanoma in both human and mouse systems,30,31 has not previously been delivered in this way. Moreover DC, which are known to harbour and disseminate pathological viruses during their transmission, and can potentially prime anti-tumour immunity after uptake of antigens from dying cells, have not been tested as cellular delivery vehicles for oncolytic viruses. Therefore, both iDC and LPS-activated mDC, as well as Tcells, were compared as cell carriers for reovirus; for initial in vitro investigations, bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC) were compared with whole splenocytes as an unpurified T-cell preparation. DC and T cells were loaded with reovirus at MOI of 0, 0.1, 1 and 10 p.f.u. per cell and cultured with B16 melanoma targets. Here, 48 and 72 h later, the melanoma cells were harvested and the percentage of tumour cells staining positive for PI was determined. DC as well as T cells were able to hitchhike reovirus for melanoma killing, and by 72 h, iDC and mDC loaded at an MOI of 1 or 10, delivered reovirus more efficiently for melanoma killing than T cells (Figure 1a). Interestingly, viral retention after loading (as determined by plaque assay of reovirus-pulsed carrier cells) was low for both T cells and DC, being less than 1% (data not shown). Thus, cells loaded at an MOI of 0.1, 1 and 10, correspond to a dose of neat reovirus of MOI 0.001, 0.01 and 0.1, respectively; at these doses however, direct reovirus results in only very low levels of B16 killing (Figure 1b), indicating that addition of neat reovirus is far less cytotoxic than delivery through cell carriage at an equivalent viral dose. This raises the possibility that infection with reovirus induces an intrinsic killer phenotype, particularly as has been previously described for DC.32 To address this, toxicity assays were repeated either leaving the suspension DC carrier cells in the coculture throughout the experiment (as in Figure 1a), or removing them after only overnight culture with B16 targets. Early removal of reovirus-loaded DC did not affect levels of tumour cell killing (Figure 1c), suggesting that the continued presence of carrier cells does not contribute to B16 death, and that DC are not acting significantly as direct cytotoxic effectors. Similarly, the early removal of carrier Tcells did not affect levels of B16 cell death (data not shown).

Figure 1.

T cells and DC are able to deliver reovirus for melanoma killing in vitro. (a) C57Bl/6 splenocytes, iDC and mDC were loaded with reovirus at the MOI indicated for 4 h at 4 °C, then washed two times in PBS and mixed with B16 melanoma targets at a 1:1 ratio. At 48 and 72 h the B16 cells were harvested and stained with PI for FACS analysis. Graphs show the mean±s.e. of data from three independent experiments; * denotes the significance of P<0.05. (b) Then, 105 B16 melanoma cells were cultured with reovirus at 0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 p.f.u. per cell for 48 or 72 h, before being harvested. Cell death was determined by FACS analysis after staining the cells with PI. Graphs show mean±s.e. of data from five independent experiments, * denotes the significance of P<0.05. (c) iDC and mDC were loaded with reovirus at the MOI indicated for 4 h at 4 °C then washed two times in PBS and mixed with B16 targets at a 1:1 ratio. After incubation overnight, the hitchhiking cells were either removed or not, and fresh medium was added. After 48 and 72 h the B16 cells were harvested and analysed by PI staining. Graphs show mean±s.e. of data from two independent experiments.

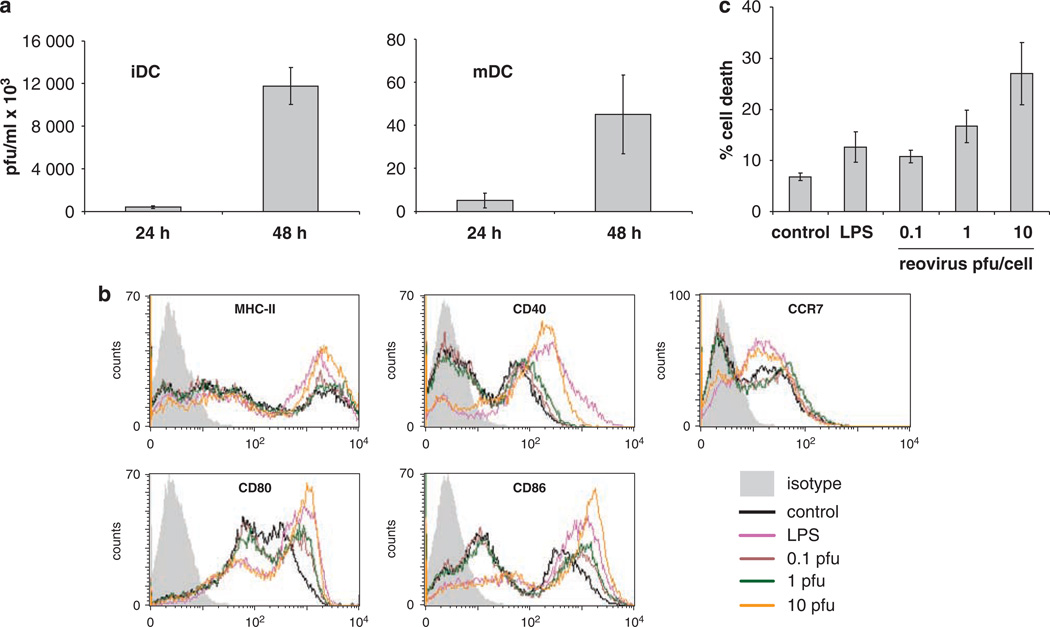

Effects of reovirus on murine DC in vitro

Unlike human DC,27 and despite their normal ras status, both murine iDC and, though to a lesser extent, mDC (note difference in y axis scale), consistently supported reovirus replication (Figure 2a), whereas T cells did not (data not shown). This may contribute to the greater target killing seen with DC carriers than with T cells (Figure 1a), as DC carry a higher toxic viral load, although there was no significant difference in tumour cytotoxicity between mDC and iDC (Figure 1a), despite higher levels of replication in iDC (Figure 2a). As previously shown for human DC,27 reovirus induced phenotypic maturation of iDC in a dose-dependent fashion, as evidenced by upregulation of MHC-II, CD40, CD80, CD86 and CCR7 (Figure 2b). Reovirus at an MOI of 1 was as efficient as LPS in stimulating DC maturation; however, increased levels of iDC death were seen at higher MOI (Figure 2c). In contrast, T cells were not susceptible to reovirus-induced cell death (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The effects of reovirus on murine BMDC. (a) DC were loaded with reovirus at MOI 10 then washed, re-suspended in medium and cultured for 24 or 48 h before being harvested, re-suspended in PBS, freeze-thawed and the presence of reovirus estimated by standard plaque assay. Graphs show the mean±s.e. of data from two independent experiments. (b and c) Then, 3 × 106 BMDC were cultured with 0, 0.1, 1, 10 p.f.u. per cell reovirus, or 100 ng ml−1 LPS. (b) MHC-II, CD40, CD80, CD86 and CCR7 expression after 24 h culture; data shown is representative of three independent experiments. (c) BMDC cell death after 48 h culture as determined by PI staining and FACS analysis. Graph shows mean±s.e. of data from five independent experiments.

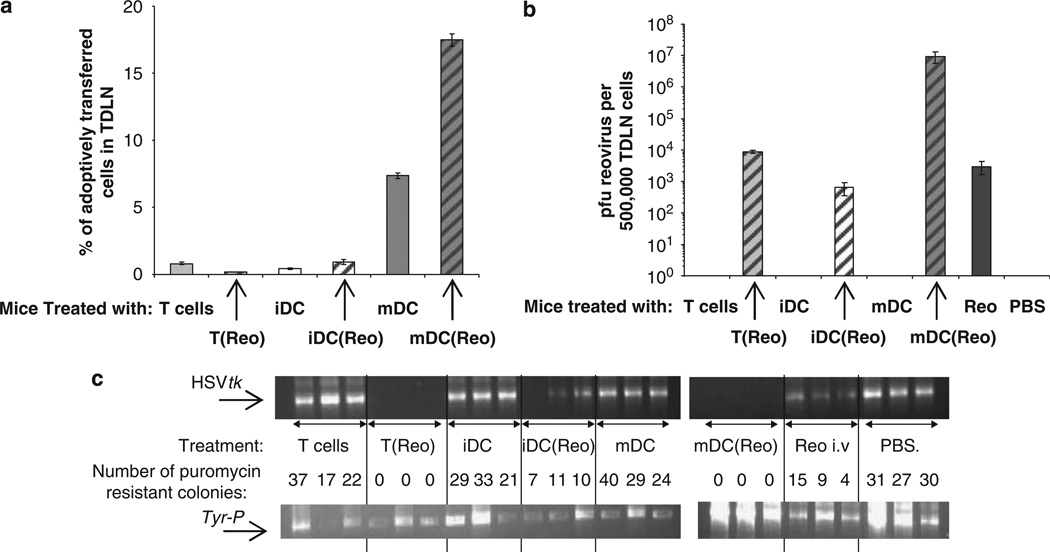

In naive mice, reovirus loaded onto T cells or DC are delivered to tumours and reduce metastatic lymph node disease at 3 days after treatment

To address the in vivo potential of DC and T cells as carriers for reovirus, a previously established mouse model was used, in which neat or cell-delivered virus is given i.v. as a single injection, 10 days after seeding a s.c. B16 tumour (B16tk) encoding the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSVtk) gene as a marker of tumour cell spread.28,33 Three days after treatment, tumour-draining lymph nodes (TDLN) and spleens were harvested and assessed for, (i) carrier cell tracking to tumour, (ii) intratumoural reovirus and (iii) early metastatic TDLN tumour cell burden (by PCR for the HSVtk transgene and by a tumour colony outgrowth assay). At 10 days TDLN and spleens were harvested and assessed for, (i) anti-viral/anti-tumour immune priming in the spleen and (ii) later TDLN metastatic disease purging, again by PCR/tumour colony outgrowth assays. iDC and mDC were compared with purified CD8+ T cells in these studies (rather than with unpurified splenocytes) to reproduce our previous in vivo system as described for VSV.16 DC maturation was also modified for in vivo therapy (as described in Materials and methods), to avoid use of potentially contaminating LPS.

In these virus-naive mice, mDC were the most effective cells at trafficking to TDLN, and their efficiency was further increased when they were loaded with reovirus at an MOI of 1 (mDC(reo), Figure 3a); some trafficking was detected for iDC loaded with reo (iDC(reo)), but detection of T(reo) was very low. Nevertheless, when levels of virus in TDLN were measured by plaque assay at this time point, high titres of reovirus were detected for mDC(reo) with lower, but still significant levels found for iDC(reo), T(reo) and neat virus (Figure 3b). It should however be noted, as stated earlier, that any cell carrier only retains <1% of the neat virus-administered dose. Hence, these data suggest that different carrier cells access TDLN with variable success after i.v. delivery (with mDC the most efficient); that loading with reovirus enhances trafficking of iDC and mDC to TDLN; and that the combination of reovirus replication in carrier DC (but not T cells) and/or metastatic tumour cells in TDLN, generates broadly comparable cell-delivered viral titres at 3 days, which is similar to that achieved by injection of an approximately 100-fold higher dose of neat virus.

Figure 3.

T cells and DC carry reovirus for metastatic melanoma killing in vivo. C57Bl/6 mice (three per group) were seeded s.c. with 5 × 105 B16tk cells. After 10 days the mice were treated with PBS, 2 × 106 p.f.u. reovirus or 2 × 106 CTB-labeled Tcells, iDC or mDC loaded at MOI of 0 or 1. After 3 days the TDLN were explanted, dissociated and analysed by FACS; the percentage of adoptively transferred cells reaching the TDLN is shown—graphs show the mean values±s.e. of data from three mice (a). Delivery of reovirus to the TDLN was determined by plaque assay (b); graphs show the mean values±s.e. of data from three mice. (c) The presence of the HSVtk and Tyr-P (control) genes were determined by PCR; in addition, the dissociated TDLN were plated in puromycin-containing medium and the number of puromycin-resistant colonies counted. Individual results for each mouse are shown; the number of colonies after treatment with T(reo), iDC(reo), mDC(reo) and neat virus were all significantly lower than controls, P<0.01. In addition, for T(reo) and mDC(reo), P<0.05 compared to both iDC(reo) and neat virus.

In terms of TDLN tumour cell clearance (measured by PCR for the HSVtk transgene and tumour colony outgrowth assay), 3 days after treatment of reovirus-naive mice bearing established s.c. tumours, disease burden was significantly reduced by neat reovirus and iDC(reo), and eliminated by mDC(reo) and T(reo) (Figure 3c). Hence, T cells and mDC carrying reovirus but not iDC(reo) or neat virus, were able to fully purge TDLN of melanoma at 3 days in this naive model, despite significant levels of viral delivery after all four treatments.

Only T cells loaded with reovirus generate an anti-tumour immune response in naive mice and control metastatic disease in TDLN at 10 days

At 3 days after treatment neat reovirus, iDC(reo), mDC(reo) and T(reo) all reduced metastatic disease burden in TDLN to some degree, with greatest control for mDC(reo) and T(reo) (Figure 3c). TDLN explanted later at 10 days showed a somewhat different disease pattern, with partial reduction of disease burden in mice treated with iDC(reo) and mDC(reo), little activity for neat virus and only major therapy for T(reo) (Figure 4a). Early lymph node purging at 3 days is probably due to direct reovirus oncolysis and/or innate immune activation and, in the absence of a developing adaptive anti-tumour immune response, the tumour may be able to re-seed the lymph node by 10 days. To further address whether 10-day tumour control in TDLN was associated with generation of an anti-tumour and/or anti-viral immune response, splenocytes from mice treated as in Figure 4a were harvested and pulsed with B16 lysate (to test specific anti-tumour immunity), or lysates from Lewis lung carcinoma cells (an irrelevant but autologous tumour line) infected with reovirus (LLC-reo), to assess anti-viral immunity; culture supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ as an indicator of response. Only splenocytes from mice treated with T(reo)-secreted IFN-γ in response to B16 lysate, indicating an anti-tumour response (Figure 4b), whereas iDC(reo)/mDC(reo)-treated mice responded only to LLC-reo, signalling generation of anti-viral immunity (Figure 4c). There was no significant IFN-γ production from any splenocytes in response to lysate from LLC cells which had not been infected with reovirus (data not shown). Hence, in reovirus-naive mice, an anti-tumour immune response to B16 lysate, associated with longer term tumour control, is generated only when reovirus is delivered on T cells (rather than neat or on DC), whereas an anti-viral rather than anti-tumour response dominates after treatment with DC(reo), precluding full tumour control in TDLN.

Figure 4.

T cells carrying reovirus prime anti-tumour immunity in naive mice. C57Bl/6 mice (three per group) were seeded s.c. with 5 × 105 B16tk cells. After 10 days the mice were treated with PBS, 2 × 106 p.f.u. reovirus or 2 × 106 CTB-labeled Tcells, iDC or mDC loaded at MOI of 0 or 1. After a further 10 days the TDLN were explanted, dissociated and screened by PCR for the presence of the HSVtk and Tyr-P (control) genes (a); in addition, the dissociated TDLN were plated in puromycin-containing medium and the number of puromycin-resistant colonies were counted (=over 100 colonies)—results shown are for individual mice; P<0.05 for T(reo), iDC(reo) and mDC(reo) compared with controls. In addition, P<0.05 for T(reo) and mDC(reo) compared with neat virus, and for T(reo) compared with iDC(reo) and mDC(reo). (b and c) Pooled splenocytes from the same mice were cultured for 48 h with B16 lysate or reovirus-infected Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC-reo) lysate and the culture supernatants were assayed for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA. Graphs show mean±s.e. of triplicate wells.

mDC are more efficient reovirus carriers than iDC or T cells in reovirus-immune mice

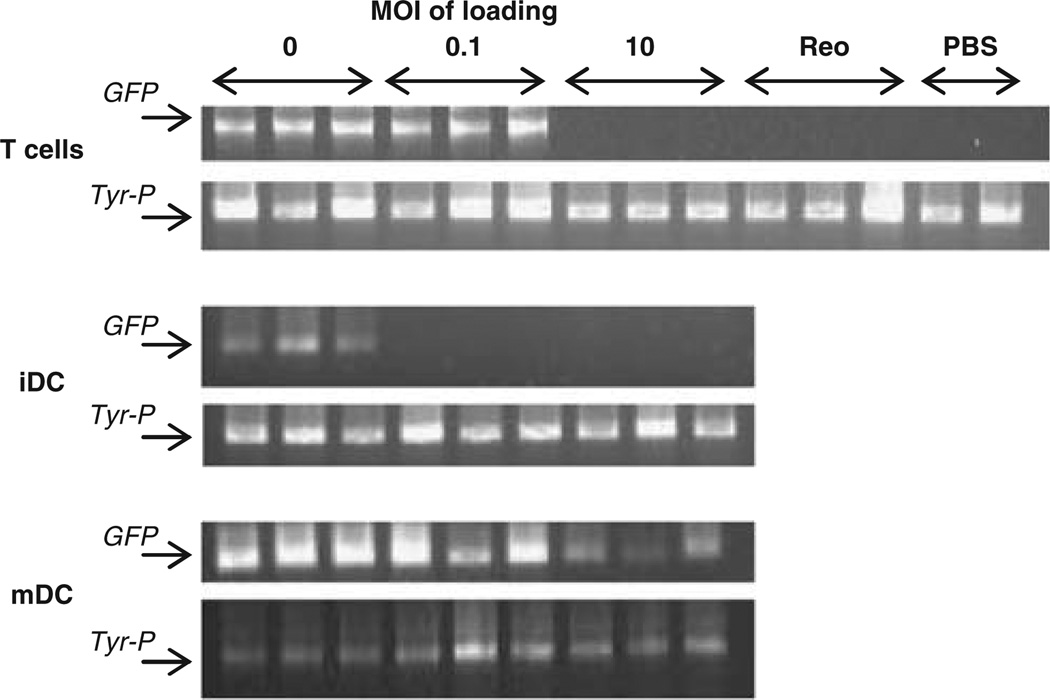

As the majority of human adults have already been exposed to reovirus and have neutralizing antibodies,25 viral delivery by T cells and DC was investigated further in reovirus-immune mice. Previous studies had shown that a loading MOI of 0.1, but not lower, was sufficient to achieve therapeutic LN purging in virus-naive animals (data not shown); therefore, trafficking and viral delivery by cells loaded at MOI of 0.1 (minimum likely effective dose) as well as at the significantly higher loading dose of MOI 10 were tested in this context. Mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 108 p.f.u. reovirus 2 weeks prior to seeding with B16tk tumour, and 10-day established tumours were treated as previously, with reovirus-loaded T cells or DC. Here, T cells and DC from GFP-transgenic mice were used as virus carriers, and cell trafficking to the TDLN was detected by highly sensitive PCR for the GFP gene. All non-loaded cells were detectable in TDLN, but no loaded iDC and only T cells loaded with the lower level of reovirus, were detected (Figure 5). In contrast, TDLN were positive for GFP in mice treated with mDC loaded with an MOI of both 0.1 and 10, although trafficking was less efficient at the higher virus dose (Figure 5). Here, titres of reovirus delivered to TDLN broadly correlated with cell trafficking; mDC delivered more virus when loaded at MOI of 0.1 than 10, and T cells only delivered virus when loaded at the lower MOI, and then less effectively than mDC (Table 1). The virus was not detected in TDLN of mice treated with loaded iDC or neat i.v. virus. As expected, even maximum reovirus delivery (by mDC(reo)), was much lower in reovirus-immune mice than in naive mice (compare titres in Figure 3b with Table 1).

Figure 5.

Only T cells loaded at a low MOI and mDC are able to traffic to TDLN for delivery of reovirus in reovirus-immune mice. Mice (three per group) were immunized with 108 p.f.u. reovirus i.p. 2 weeks later the mice were seeded s.c. with 2 × 105 B16tk cells. After a further 10 days, the mice were treated with PBS, 2 × 107 p.f.u. reovirus or 2 × 106 T cells, iDC or mDC from GFP-transgenic mice loaded at MOI of 0 or 0.1 or 10. 3 days later the TDLN were explanted and dissociated. The presence of adoptively transferred cells was assessed by PCR screening for the presence of the GFP and Tyr-P (control) genes.

Table 1.

Reovirus delivery to TDLN; p.f.u. per 500 000 cells

| Loading MOI |

2 × 107 reo | PBS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 10 | |||

| T cells | 0 | 5000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 10 000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| iDC | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| mDC | 0 | 300 000 | 400 | ||

| 0 | 4000 | 0 | |||

| 0 | 100 000 | 8000 | |||

Mice (3 per group) were immunized with 108 p.f.u. reovirus i.p. After 2 weeks the mice were seeded s.c. with 2 × 105 B16tk cells. After a further 10 days, the mice were treated with PBS, 2 × 107 pfu reovirus or 2 × 106 T cells, iDC or mDC loaded with reovirus as indicated. After 3 days TDLN were removed and viral delivery was determined by plaque assay.

Most important, although T cells loaded at MOI 0.1, and mDC loaded at 0.1 and, to a lesser degree 10, reduced TDLN disease burden at 3 days, neither iDC nor neat virus were able to control metastases in this immunized model (Table 2). Hence, carrier cell trafficking, reovirus delivery and early tumour clearance all correlated in the context of prior reovirus immunization, and the pattern and success of therapy was very different to that seen in naive mice.

Table 2.

Early tumour burden in reovirus-immune mice after treatment

| Loading MOI |

2 × 107 reo | PBS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 10 | |||

| T cells | >30 | 7 | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| >30 | 0 | >30 | >30 | >30 | |

| >30 | 15 | >30 | >30 | ||

| iDC | >30 | >30 | >30 | ||

| >30 | >30 | >30 | |||

| >30 | >30 | >30 | |||

| mDC | >30 | 0 | 15 | ||

| >30 | 70 | 25 | |||

| >30 | 0 | 0 | |||

Mice (3 per group) were immunized with 108 pfu reovirus i.p. After 2 weeks the mice were seeded s.c. with 2 × 105 B16tk cells. After a further 10 days, the mice were treated with PBS, 2 × 107 p.f.u. reovirus or 2 × 106 T cells, iDC or mDC loaded with reovirus as indicated. After 3 days TDLN were removed and metastatic burden was determined by puromycin-resistant colony outgrowth.

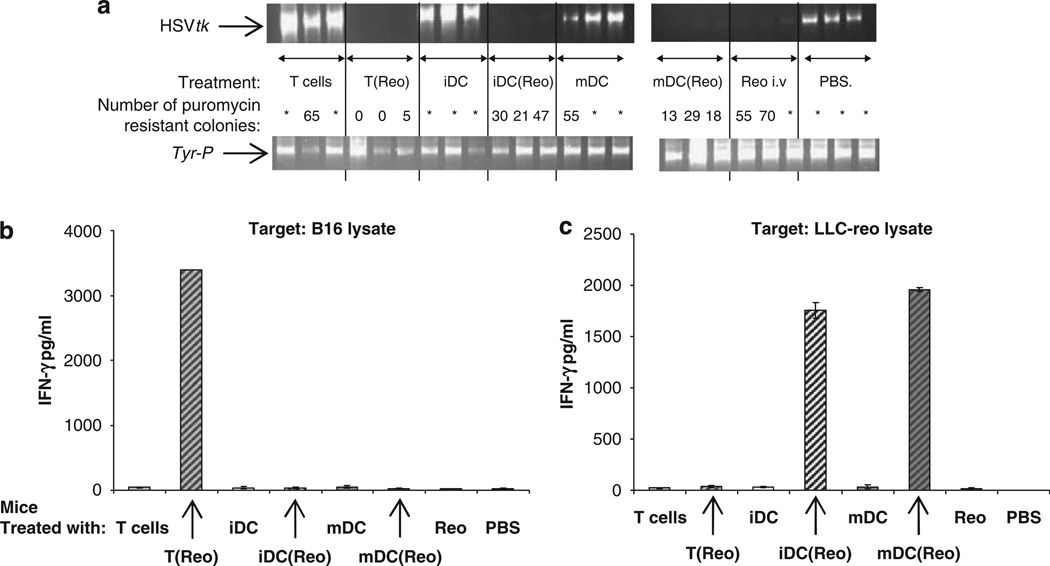

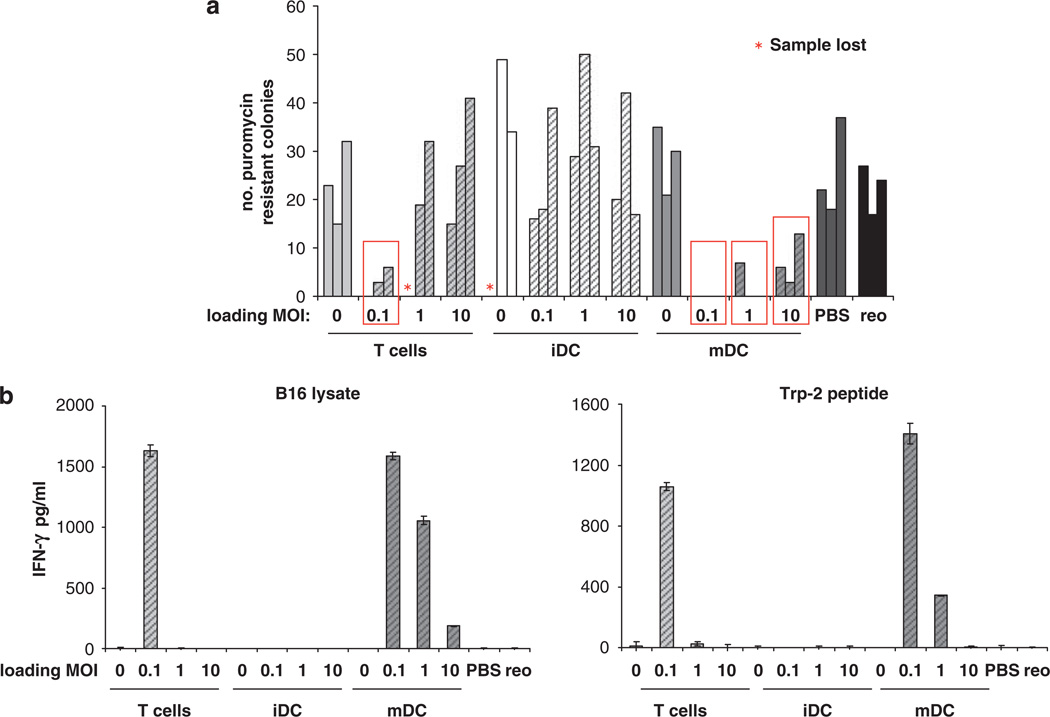

mDC(reo) are most potent for later tumour control and anti-tumour immune priming in reovirus-immune mice

In the next experiments in mice immunized against reovirus, established tumours were treated with T cells/DC loaded with reovirus at MOI 0, 0.1, 1 or 10, and 10 days later TDLN were explanted and tested for the presence of B16tk cells (as for naive mice in Figure 4a). Similar to the results in immunized mice 3 days after treatment, T(reo) at the lowest MOI cleared LN of metastases, whereas iDC(reo) were completely ineffective at all virus dose levels (Figure 6a). mDC(reo) at MOI 0.1 completely purged metastatic B16tk cells with less, though detectable, purging following treatment with mDC loaded at higher MOI. As in naive mice, the longer term purging of LN was associated with development of an anti-tumour immune response; only T(reo)/MOI 0.1 and reovirus-loaded mDC generated immunity against both whole melanoma lysate and the TAA epitope TRP-2 (Figure 6b). There was no reactivity against a control ovalbumin-derived peptide SIINFEKL (data not shown). Therefore, as in naive mice, the level of anti-tumour immune priming in spleens of treated mice correlated with the success of long-term TDLN purging. Spleens of all immunized mice secreted high levels of IFN-γ (over 300 pg ml−1) on pulsing with LLC-reo lysate, but none in response to LLC lysate (data not shown). Hence, in mice immune to oncolytic reovirus, mDC are the most effective cell carriers for viral delivery, tumour therapy and priming of anti-tumour immunity, over the widest range of reovirus loading doses.

Figure 6.

T cells and mDC carrying reovirus prime anti-tumour immunity in virus-immune mice. Mice (three per group) were immunized with 108 p.f.u. reovirus i.p. After 2 weeks the mice were seeded s.c. with 2 × 105 B16tk cells. After a further 10 days, the mice were treated with PBS, 2 × 107 p.f.u. reovirus or 2 × 106 T cells, iDC or mDC loaded at MOI of 0 or 0.1, 1 or 10. 10 days later the TDLN and spleens were explanted. Dissociated LN cells were cultured in medium containing puromycin and the number of puromycin-resistant colonies were counted (a); bars represent individual mice and show the number of puromycin-resistant colonies per 500 000 LN cells; red boxes denote significance compared with PBS control (P<0.05). (b) Pooled splenocytes were cultured for 48 h in the presence of the indicated peptide or cell lysates, and the culture supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ by ELISA; graphs show mean±s.e. of triplicate wells.

Discussion

Metastatic melanoma is a disease for which there is currently no effective therapy and new approaches are therefore needed. One approach currently under investigation is the use of oncolytic viruses, either alone or in combination with standard therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Reovirus is one oncolytic virus which is cytotoxic to melanoma,30 but its systemic delivery is likely to be hampered by the presence of neutralizing anti-reovirus antibodies.26 Delivery of VSV through antigen-specific or non-specific lymphocytes for the therapy of murine melanoma has been shown to be more potent than delivery of neat virus for both direct cytotoxicity and priming of anti-tumour immunity,16,20 whereas intravenous reovirus alone also has limited efficacy against melanoma in vivo.31 Here, we show for the first time that reovirus can also be loaded onto non-antigen-specific T cells for effective delivery to lymph node metastases, and that DC represent an alternative potential cell carrier for oncolytic viral therapy.

In vitro, both DC and Tcells loaded with reovirus were more cytotoxic to melanoma cells than an equivalent dose of neat reovirus; in addition, DC were more efficient carriers than T cells (Figure 1a). Although reovirus matured DC (Figure 2b), it did not appear to induce significant killer activity in these cells (Figure 1c); this is in agreement with our previous observation in a human system, where reovirus similarly matured DC but did not induce DC cytotoxicity.27 The higher level of melanoma killing seen when DC rather than T cells were used as carriers, may be due to viral replication in DC (Figure 2a) and/or closer interaction between DC and tumour target cells, leading to better viral ‘hand-off’.

In naive mice, direct viral oncolysis appears to contribute significantly to early 3 day purging of the lymph node, as tumour clearance was associated with detection of significant viral titres (Figure 3b/c). It is noteworthy, however, that the efficiency of carrier cell trafficking to TDLN (Figure 3a), did not correlate with the titre of virus, which is subsequently detected (Figure 3b). This may be due to differences in the efficiency of viral hand-off, replication, spread and clearance following delivery by different cells. In addition, with regard to tumour clearance at 3 days, other mechanisms such as non-specific innate immune activation are likely to come into play. In support of this, we have found that intravenous cellular delivery of reovirus results in rapid induction of general splenic activation in vivo (unpublished data).

For longer term purging, generation of a specific anti-tumour immune response appears to be involved which, in naive mice, was only induced when T cells were the reovirus carriers (Figure 4). This was unexpected, as potentially DC might enhance anti-tumour adaptive immunity.34 However, in a naive mouse, although mDC in particular delivered reovirus effectively to the TDLN (Figure 3a), the immune response generated was anti-viral rather than anti-tumour (Figure 4b/c), probably due to the high level of viral antigen presented by reovirus-permissive DC. Where Tcells (in which reovirus does not replicate) were the viral carriers, no such anti-viral immunity ensued (Figure 4c). We hypothesize that this allowed anti-tumour immunity (arising from cross-priming by endogenous lymph node DC of TAA released by dying tumour cells) to develop, thus supporting effective tumour clearance.

The relevance of a virus-naive mouse model is uncertain, since most human adults have been exposed to reovirus and possess anti-reoviral antibodies,25 which are likely to neutralize the virus on systemic delivery. We therefore investigated reovirus hitchhiking by T cells and DC in reovirus-immune mice. Here, the results were strikingly different. Lower reovirus loading correlated with better delivery to the TDLN, particularly for mDC, whereas iDC were ineffective as reovirus carriers, failing to reach the node/deliver reovirus even when loaded at a low MOI (Figure 5, Table 1). The reduction in trafficking of mDC/T cells loaded with higher levels of virus, and the failure of reovirus-loaded iDC to traffic to TDLN at all, may be due to anti-reovirus antibody binding eliminating hitchhiking cells by scavenging or complement attack. The ability of different carrier cells to ‘hide’ virus from such clearance has been reported previously,35 and may involve multiple cellular mechanisms, including whether the carrier cell is permissive for viral replication. In our system in immunized mice, a high level of reovirus replication in iDC (Figure 2a) was associated with abolition of cell trafficking even at low viral load (Figure 5), despite CCR7 expression by these cells (Figure 2b), suggesting that the higher level of reovirus replication does lead to rapid cell carrier elimination. The multiple factors controlling carrier cell clearance tracking to the lymph node and oncolytic viral delivery, in virus versus naive mice, await full characterization; nevertheless, the current data clearly highlights the importance of cell choice and virus dose selection when planning clinical protocols for patients who already carry anti-viral antibodies, and/or are likely to rapidly develop them with multiple treatments. It is also noteworthy that in this model reovirus delivered neat, without hitchhiking, was entirely unable to access the TDLN in reovirus-immune mice (Table 1).

The level of reovirus found in the TDLN at early time points in reovirus-immune mice was relatively low compared with that found in naive mice (Table 1 versus Figure 3b), suggesting that direct oncolysis may play a less significant role in the reduction in tumour burden at 3 days following treatment of immune mice with reovirus-loaded carrier cells. As mentioned above, the presence of reovirus in the TDLN may lead to activation of an innate immune response, which might be therapeutically more significant in the context of pre-existing anti-viral immunity. For example, activated DC recruit NK cells to the lymph node,36 and reovirus can activate DC to support both NK and T cell innate anti-tumour immunity.27 In addition, reovirus induces IFN-α, which in turn activates NK cells to secrete the inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α, and also to increase their cytotoxic activity.37 Thus, a major immune effect of reovirus may be as an adjuvant, supporting both early innate and later specific arms of the immune system. In the immune mouse, as in the virus-naive, longer term 10-day tumour control was associated with the induction of specific anti-tumour immunity (Figure 6). Thus, pre-established anti-viral immunity did not absolutely preclude subsequent anti-tumour priming by appropriate cell carriers/viral dose, which is encouraging for clinical application.

Although the disease model used in this study is primarily focused on reovirus delivery/replication and tumour purging of lymph nodes, oncolytic virus delivery on immune carrier cells may also impact on the primary tumour. Across three experiments in virus-naive and immune mice, we did observe a trend towards decreased size of the primary tumours in mice treated with immune cells carrying reovirus, compared to mice treated with immune cells alone or PBS. However, this treatment of the primary tumour only reached statistical significance in one of the three experiments by 10 days post adoptive transfer of the virus-loaded cells (P=0.04 for treatment with mDC(Reo) compared with mDC alone, or P<0.01 versus PBS). Moreover, this trend was not associated with the detection of virus in the primary tumour, consistent with the hypothesis that LN purging is due to virus delivery and oncolysis of tumour cells in the lymphoid organs. Studies using a more controlled primary tumour model are underway to demonstrate definitively whether immune cell-mediated viral delivery to metastases in the lymphoid organs can reproducibly generate immune-based therapy of primary tumours.

From the current data, it is not possible to precisely define the ideal cell carrier and reovirus dose for human clinical application. This study does, however, highlight that the viral dose and mode of delivery, as well as the viral immune status of the individual, may profoundly affect the success of any clinical anti-tumour viral therapy. Significantly, one conclusion from a recent phase I trial of i.v. reovirus therapy for cancer is that pre-existing and rapidly induced neutralizing anti-reovirus antibody may be a potential obstacle to clinical use of the virus.38

In our model, a reduction in later tumour burden is consistently associated with the induction of an anti-tumour adaptive immune response; however, further work is required to more precisely define the role of the innate immune response, together with direct oncolysis, in early tumour control. DC are an effective alternative delivery cell for oncolytic viral delivery, and appear more effective than T cells for delivery of a higher therapeutic dose in the face of anti-viral immunity (Table 1). An improved understanding of the multiple factors controlling the efficacy of viral treatments for cancer, particularly in terms of limitation or enhancement of therapy by the interplay between anti-viral and anti-tumour immune priming, will support optimization of pre-clinical human testing and trial protocol development for this promising novel anti-cancer strategy.

Materials and methods

Cells and virus

Reovirus Dearing Type 3 was provided by Oncolytics Biotech Inc. (Calgary, Canada) and stored in PBS at 4 °C (maximum 3 months) or at −80 °C for longer term storage. Virus titres were measured by a standard plaque assay on L929 cells.

The murine melanoma line B16 (H2-Kb) was grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) with 10% (v v−1) FCS (Biosera, Ringmer, UK) and 2 mm l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK). B16tk cells were derived from B16 cells by transducing them with a cDNA encoding the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (tk) gene39 and were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v v−1) FCS, l-glutamine and 1.25 µg ml−1 puromycin selection. Cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma and found to be free of infection.

Preparation of C57Bl/6 lymphocytes and dendritic cells

Murine splenocytes were isolated from C57Bl/6 mice by crushing spleens through a 100 µm filter to create a single cell suspension. Red blood cells were removed by 2 min incubation in ACK buffer (sterile distilled H2O containing 0.15 m NH4Cl, 1.0 mm KHCO3 and 0.1 mm EDTA adjusted to pH 7.2–7.4). Remaining cells were washed and cultured in DMEM with 5% FCS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) and 50 µm β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Where indicated, CD8+ lymphocytes were further purified by treating spleens and lymph nodes as above, followed by isolation using the MACS CD8a (Ly-2) microbead magnetic cell-sorting system (Miltenyi-Biotec, Woking, UK). FACS analysis showed that the cultures were typically >98% CD8+ T cells, <2% CD4+ T cells and <0.1% NK1.1+ cells (data not shown). Viable cells were purified by density gradient centrifugation with Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, Ontario, Canada).

Murine BMDC were prepared from C57Bl/6 mice as described earlier.40,41 Briefly, bone marrow was removed from the femur and tibia by flushing into RPMI-1640. To enrich for dendritic cell precursors, cells were incubated with biotinylated antibodies to B220, I-A, Gr1, CD3 and CD4 (BD-Pharmingen, Oxford, UK), washed, incubated with streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi-Biotech) and passed through a magnetic cell separation column (Miltenyi-Biotech). Eluted cells were cultured for 7 days as described earlier, at which point approximately 70% were CD11c+ by flow cytometry (immature, iDC). BMDC were matured for in vitro experiments with 100 ng ml−1 LPS (Sigma) for 24 h (mature, mDC). To avoid any possibility of direct LPS-induced effects in the in vivo experiments, iDC were grown as described above, but maturation was instead carried out by harvesting the iDC between day 5 and day 8, and re-plating them in fresh medium at a maximum of 1 × 106 cells per ml for a further 24–48 h.42 Preliminary experiments showed that the DC phenotypic maturation was equally effective whether triggered by addition of LPS or re-plating (data not shown).

In vitro hitchhiking

Target B16 cells were seeded at 105 cells per well in six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Reovirus was added to the wells at 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1 or 10 p.f.u. per cell, or 106 T cells, iDC and mDC were loaded with reovirus at 0, 0.1, 1 and 10 p.f.u. per cell in 1 ml PBS at 4 °C for 4 h, washed two times in PBS, re-suspended and added to the target cells at a 1:1 ratio (105 cells per well). After a further 48 and 72 h, wells were harvested, cells were labelled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11c or anti-CD3 (BD-Pharmingen) to allow gating out of carrier DC and T cells respectively, stained with propidium iodide (Sigma) and analysed for B16 cell death by flow cytometry using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). In some experiments the virus-loaded cells were removed after 18 h culture, wells were washed with PBS and fresh culture medium was added.

In vivo studies

All procedures were approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. C57Bl/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbour, ME, USA) at 6–8 weeks of age. Reovirus-immune mice were generated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) immunization with 108 p.f.u. reovirus, 2 weeks prior to B16tk tumour seeding. To establish s.c. tumours meta-static to lymph nodes, 2–5 × 105 B16tk cells were injected in 100 µl PBS into the flanks of mice (three mice per group for each readout). After 10 days, mice were treated i.v. with: PBS; neat reovirus (equivalent to the highest cell loading dose in that experiment); 2 × 106 T cells, iDC or mDC loaded at 0, 0.1, 1 or 10 p.f.u. per cell for 4 h at 4 °C. Tumour draining lymph nodes (TDLN) were explanted at 3 or 10 days post treatment; spleens were explanted 10 days post treatment.

Determination of viral titre

Hitchhiking cells loaded with reovirus as described above were cultured in vitro for 24 or 48 h, or TDLN from treated mice were dissociated immediately after excision. Cells were then treated with 3 cycles of freeze/thaw and viral titre was determined using a standard plaque assay on L929 cells; in vivo values were normalized to p.f.u. per 500 000 dissociated LN cells.

In vivo tracking of adoptively transferred DC and T cells

C57Bl/6 DC and lymphocytes were labelled with CellTracker Blue (7-amino-4-chloromethylcoumarin; Invitrogen) and injected i.v. into 10-day tumour-bearing mice. After 3 days the TDLN were explanted from three mice per group and dissociated in vitro. Then, 1 × 106 cells were washed in PBS containing 0.1% BSA, re-suspended in 500 ml PBS containing 4% formaldehyde and analysed by flow cytometry using CellQuest software. The total number of adoptively transferred cells in the LN was calculated from: ((no. of CTB+ve events recorded from FACS of 5000 excised LN cells) × (total no. of LN cells recovered))÷5000.

In tracking experiments in reovirus-immune mice, lymphocytes and DC from mice expressing the enhanced green fluorescent protein driven by chicken β-actin promoter and CMV intermediate early enhancer on a C57Bl/6 background were used as a means of avoiding the CellTracker Blue labelling step. However, GFP-expressing T cells/DC could not be detected by FACS (data not shown); therefore, PCR for GFP was used to identify injected cells in the TDLN instead. Genomic DNA from lymph nodes was prepared with the DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), 10 ng of DNAwas amplified by PCR with primers specific for GFP. As a control, PCR was performed with primers specific for a genomic fragment of the murine tyrosinase promoter (Tyr-P). In all experiments, a mock PCR (without added DNA) was performed to exclude contamination (not shown).

PCR screening for B16tk tumour cells

Genomic DNA from lymph nodes was prepared with the DNeasy kit. Then, 10 ng of DNA was amplified by PCR with primers specific for HSVtk, which is stably integrated into the genome of B16tk tumour cells. Control and mock PCR was carried out as detailed above.

Puromycin-resistant colony outgrowth assay to detect metastatic B16tk tumour cells

B16tk tumour cells stably express the puromycin-resistance gene, allowing for growth in puromycin. To select for viable B16tk cells present at resection, 1×106 cells from dissociated TDLN were plated in six-well plates with 1.25 µg ml−1 puromycin. Every 2–3 days cultures were washed and fresh puromycin-containing medium was added. After 7–10 days, individual puromycin-resistant colonies were counted in wells.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for IFN-γ secretion

Here, 7.5 × 105-pooled day-10 splenocytes from treated mice were plated into 24-well plates in triplicate and incubated at 37 °C, with 5 µg ml−1 of appropriate peptide or cell lysate (equivalent to ~106 cells) being added every 24 h. Cell-free supernatants were collected after 48 h and tested by specific ELISA for IFN-γ according to the manufacturer’s instructions (OptEIA IFN-γ kit; BD Biosciences). The synthetic, H2-Kb-restricted peptides TRP-2180–188 SVYDFFVWL and control ovalbumin SIIN-FEKL were synthesized at the Mayo Foundation Core Facility.

Statistics

The Student’s t-test was used; statistical significance was determined at the level of P<0.05.

Acknowledgements

We thank Oncolytics Biotech (http://www.oncolyticsbiotech.com) for providing reovirus. This work was funded by Cancer Research UK, and by the Richard M. Schulze Family Foundation, the Mayo Foundation and by NIH Grants CA RO1107082-02 and RO1130878.

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- iDC

immature DC

- mDC

mature DC

- BMDC

bone marrow-derived dendritic cells

- HSVtk

herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- TAA

tumour-associated antigens

- T(reo)/DC(reo)

T cells/DC loaded with reovirus

- TDLN

tumour-draining lymph nodes

- VSV

vesicular stomatitis virus

References

- 1.Aghi M, Martuza RL. Oncolytic viral therapies—the clinical experience. Oncogene. 2005;24:7802–7816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu TC, Kirn D. Systemic efficacy with oncolytic virus therapeutics: clinical proof-of-concept and future directions. Cancer Res. 2007;67:429–432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pizzato M, Marlow SA, Blair ED, Takeuchi Y. Initial binding of murine leukemia virus particles to cells does not require specific Env-receptor interaction. J Virol. 1999;73:8599–8611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8599-8611.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons M, Onion D, Green NK, Aslan K, Rajaratnam R, Bazan-Peregrino M, et al. Adenovirus type 5 interactions with human blood cells may compromise systemic delivery. Mol Ther. 2006;14:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worgall S, Wolff G, Falck-Pedersen E, Crystal RG. Innate immune mechanisms dominate elimination of adenoviral vectors followingin vivoadministration. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:37–44. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye X, Jerebtsova M, Ray PE. Liver bypass significantly increases the transduction efficiency of recombinant adenoviral vectors in the lung, intestine, and kidney. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:621–627. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devaux P, Christiansen D, Plumet S, Gerlier D. Cell surface activation of the alternative complement pathway by the fusion protein of measles virus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1665–1673. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79880-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakimoto H, Ikeda K, Abe T, Ichikawa T, Hochberg FH, Ezekowitz RA, et al. The complement response against an oncolytic virus is species-specific in its activation pathways. Mol Ther. 2002;5:275–282. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai V, Johnson DE, Rahman A, Wen SF, LaFace D, Philopena J, et al. Impact of human neutralizing antibodies on antitumor efficacy of an oncolytic adenovirus in a murine model. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7199–7206. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Yu DC, Charlton D, Henderson DR. Pre-existent adenovirus antibody inhibits systemic toxicity and antitumor activity of CN706 in the nude mouse LNCaP xenograft model: implications and proposals for human therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:1553–1567. doi: 10.1089/10430340050083289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher K. Striking out at disseminated metastases: the systemic delivery of oncolytic viruses. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2006;8:301–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croyle MA, Chirmule N, Zhang Y, Wilson JM. PEGylation of E1-deleted adenovirus vectors allows significant gene expression on readministration to liver. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1887–1900. doi: 10.1089/104303402760372972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green NK, Herbert CW, Hale SJ, Hale AB, Mautner V, Harkins R, et al. Extended plasma circulation time and decreased toxicity of polymer-coated adenovirus. Gene Therapy. 2004;11:1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bangari DS, Mittal SK. Current strategies and future directions for eluding adenoviral vector immunity. Curr Gene Ther. 2006;6:215–226. doi: 10.2174/156652306776359478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bian H, Fournier P, Moormann R, Peeters B, Schirrmacher V. Selective gene transfer to tumor cells by recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus via a bispecific fusion protein. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiao J, Kottke T, Willmon C, Galivo F, Wongthida P, Diaz RM, et al. Purging metastases in lymphoid organs using a combination of antigen-nonspecific adoptive T cell therapy, oncolytic virotherapy and immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2008;14:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nm1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iankov ID, Blechacz B, Liu C, Schmeckpeper JD, Tarara JE, Federspiel MJ, et al. Infected cell carriers: a new strategy for systemic delivery of oncolytic measles viruses in cancer virotherapy. Mol Ther. 2007;15:114–122. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Power AT, Wang J, Falls TJ, Paterson JM, Parato KA, Lichty BD, et al. Carrier cell-based delivery of an oncolytic virus circumvents antiviral immunity. Mol Ther. 2007;15:123–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorne SH, Contag CH. Integrating the biological characteristics of oncolytic viruses and immune cells can optimize therapeutic benefits of cell-based delivery. Gene Therapy. 2008;15:753–758. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiao J, Wang H, Kottke T, Diaz RM, Willmon C, Hudacek A, et al. Loading of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus onto antigen-specific Tcells enhances the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy of tumors. Gene Therapy. 2008;15:604–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorne SH, Negrin RS, Contag CH. Synergistic antitumor effects of immune cell-viral biotherapy. Science. 2006;311:1780–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1121411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prestwich RJ, Harrington KJ, Pandha HS, Vile RG, Melcher AA, Errington F. Oncolytic viruses: a novel form of immunotherapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:1581–1588. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.10.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comins C, Heinemann L, Harrington K, Melcher A, De Bono J, Pandha H. Reovirus: viral therapy for cancer ‘as nature intended’. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coffey MC, Strong JE, Forsyth PA, Lee PW. Reovirus therapy of tumors with activated Ras pathway. Science. 1998;282:1332–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tai JH, Williams JV, Edwards KM, Wright PF, Crowe JE, Jr, Dermody TS. Prevalence of reovirus-specific antibodies in young children in Nashville, Tennessee. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1221–1224. doi: 10.1086/428911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White CL, Twigger KR, Vidal L, De Bono JS, Coffey M, Heinemann L, et al. Characterization of the adaptive and innate immune response to intravenous oncolytic reovirus (Dearing type 3) during a phase I clinical trial. Gene Therapy. 2008;15:911–920. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Errington F, Steele L, Prestwich R, Harrington KJ, Pandha HS, Vidal L, et al. Reovirus activates human dendritic cells to promote innate antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:6018–6026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prestwich RJ, Errington F, Ilett EJ, Morgan RS, Scott KJ, Kottke T, et al. Tumor infection by oncolytic reovirus primes adaptive antitumor immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7358–7366. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole C, Qiao J, Kottke T, Diaz RM, Ahmed A, Sanchez-Perez L, et al. Tumor-targeted, systemic delivery of therapeutic viral vectors using hitchhiking on antigen-specific T cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nm1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Errington F, White CL, Twigger KR, Rose A, Scott K, Steele L, et al. Inflammatory tumour cell killing by oncolytic reovirus for the treatment of melanoma. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1257–1270. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao J, Wang H, Kottke T, White C, Twigger K, Diaz RM, et al. Cyclophosphamide facilitates antitumor efficacy against subcutaneous tumors following intravenous delivery of reovirus. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:259–269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang J, Tatsumi T, Pizzoferrato E, Vujanovic N, Storkus WJ. Nitric oxide sensitizes tumor cells to dendritic cell-mediated apoptosis, uptake, and cross-presentation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8461–8470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diaz RM, Galivo F, Kottke T, Wongthida P, Qiao J, Thompson J, et al. Oncolytic immunovirotherapy for melanoma using vesicular stomatitis virus. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2840–2848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunzer M, Janich S, Varga G, Grabbe S. Dendritic cells and tumor immunity. Semin Immunol. 2001;13:291–302. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Power AT, Bell JC. Cell-based delivery of oncolytic viruses: a new strategic alliance for a biological strike against cancer. Mol Ther. 2007;15:660–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivori S, Falco M, Della Chiesa M, Carlomagno S, Vitale M, Moretta L, et al. CpG and double-stranded RNA trigger human NK cells by Toll-like receptors: induction of cytokine release and cytotoxicity against tumors and dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10116–10121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403744101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidal L, Pandha HS, Yap TA, White CL, Twigger K, Vile RG, et al. A phase I study of intravenous oncolytic reovirus type 3 dearing in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7127–7137. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vile RG, Hart IR. Use of tissue-specific expression of the Herpes Simplex virus thymidine kinase gene to inhibit growth of established murine melanomas following direct intratumoural injection of DNA. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3860–3864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melcher A, Todryk S, Bateman A, Chong H, Lemoine NR, Vile RG. Adoptive transfer of immature dendritic cells with autologous or allogeneic tumor cells generates systemic anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2802–2805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merrick A, Diaz RM, O’Donnell D, Selby P, Vile R, Melcher A. Autologous versus allogeneic peptide-pulsed dendritic cells for anti-tumour vaccination: expression of allogeneic MHC supports activation of antigen specific T cells, but impairs early naive cytotoxic priming and anti-tumour therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:897–906. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallucci S, Lolkema M, Matzinger P. Natural adjuvants: endogenous activators of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:1249–1255. doi: 10.1038/15200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]