Abstract

Catastrophic floods generated ~3.2 Ga by rapid groundwater evacuation scoured the Solar System’s most voluminous channels, the southern circum-Chryse outflow channels. Based on Viking Orbiter data analysis, it was hypothesized that these outflows emanated from a global Hesperian cryosphere-confined aquifer that was infused by south polar meltwater infiltration into the planet’s upper crust. In this model, the outflow channels formed along zones of superlithostatic pressure generated by pronounced elevation differences around the Highland-Lowland Dichotomy Boundary. However, the restricted geographic location of the channels indicates that these conditions were not uniform Boundary. Furthermore, some outflow channel sources are too high to have been fed by south polar basal melting. Using more recent mission data, we argue that during the Late Noachian fluvial and glacial sediments were deposited into a clastic wedge within a paleo-basin located in the southern circum-Chryse region, which was then completely submerged under a primordial northern plains ocean. Subsequent Late Hesperian outflow channels were sourced from within these geologic materials and formed by gigantic groundwater outbursts driven by an elevated hydraulic head from the Valles Marineris region. Thus, our findings link the formation of the southern circum-Chryse outflow channels to ancient marine, glacial, and fluvial erosion and sedimentation.

At the end of the Noachian Period Mars experienced an abrupt transition into a climate dominated by extremely cold and dry conditions, which resulted in the subsequent confinement of the planet’s hydrosphere in highly pressurized aquifers beneath thick upper crustal permafrost materials1,2. A popular model proposes that the vast Noachian surface water systems were cold-trapped in the planet’s south polar region to form an ice cap, which gradually infiltrated into a global mega-regolith as a consequence of pressure-induced basal melting1,2. The catastrophic floods that excavated the Late Hesperian southern circum-Chryse outflow channels3 would have occurred in zones where the elevation difference between the Martian south polar region and lower terrains generated superlithostatic pressures1,2.

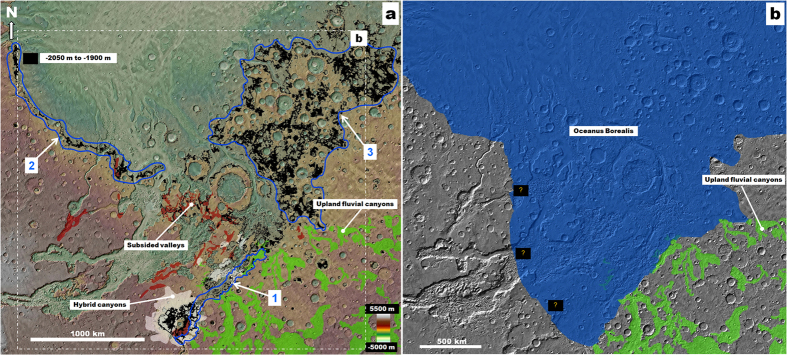

In order to explain the relative localized occurrence4,5 of catastrophic-flood-formed Martian outflow channels, it was hypothesized that the causative flooding emanated from a compartmentalized global hydrosphere that was also contained within a planetwide megaregolith6. In this model, the existence of high elevation outflow channels in the circum-Chryse region7,8 can be explained by the presence of an aquifer system that extended from the Tharsis Montes to the outflow channel head source regions9. It was subsequently discovered that rather than possessing global megaregolith, much of the Martian upper crust appears to be dominated by Noachian sedimentary deposits of great stratigraphic thicknesses that both infill and bury numerous impact craters10,11. Hence, it was proposed that, instead of a megaregolith-trapped hydrosphere1,2,6, significant portions of these outflow-channel-source (OFCS) aquifers might have consisted of water-ice contained within buried impact craters and impact-fractured rocks12,13. However, because the sedimentary deposits are distributed globally on Mars, the unique conditions leading to the formation of the southern circum-Chryse outflow channel source regions are still poorly understood. Here, we propose a new geologic model linking the development of OFCS aquifers within the highlands of southern circum-Chryse (Fig. 1a) to a stage of Late Noachian large-scale regional marine sedimentation.

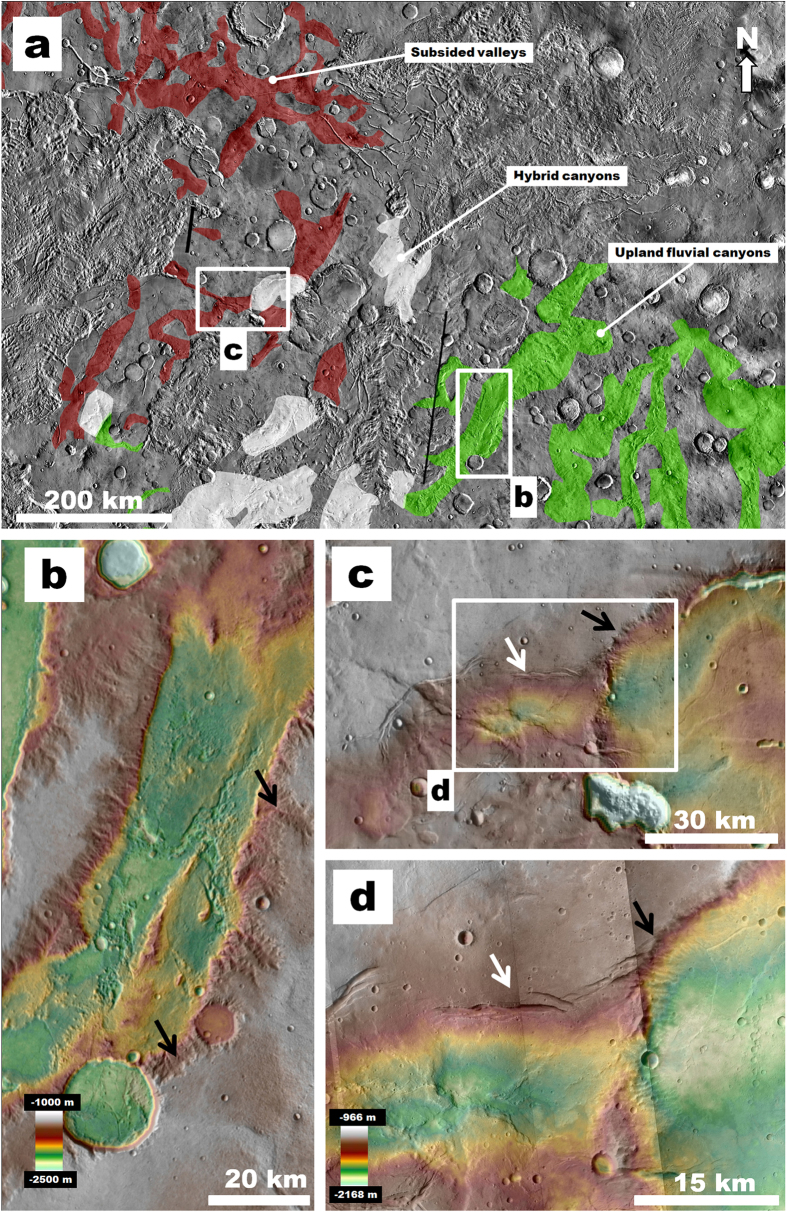

Figure 1.

(a) Context topographic view of southern circum-Chryse and eastern Valles Marineris showing cited geographic features (MOLA DEM, 460 m/pixel centered at 3.18° S; 332.10° E). (b) Geomorphic map of southern circum-Chryse showing the distribution of Noachian fluvial canyons, subsided surfaces, chaotic terrains and outflow channels. Black arrows show the inferred directions of surface flows along the upland canyons. Dashed yellow line traces an equatorial belt of chaotic terrains. (c) Close-up view on panel b shows the most extensive zone of subsidence in southern circum-Chryse, including the distribution of fault systems (white lines) in the region. (d,e) Close-up views on a subsided valley that exhibit faulted slope breaks (white arrows). We produced the maps in this figure using Esri’s ArcGIS geographic information system.

Results and interpretative synthesis

The long-held view is that regional groundwater outbursts led to the formation of extensive chaotic terrains (collapsed upper crustal materials) that are the sources of the southern circum-Chryse outflow channels5,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. More recently, zones of surface subsidence have been recognized as including much more extensive areas of adjacent highlands12,13,21. Consequently, the distribution of regional highland surfaces modified by collapse and subsidence were proposed to demark the approximate extent of the OFCS aquifers12,13.

These chaotic terrains have been mapped in detail by previous investigators4,16,22, and here we present the first map showing the full extent of highland subsidence in this region of the planet (Fig. 1b,c). We show that these previously unmapped subsidence zones modify large areas of the highlands and connect eastern Valles Marineris to the initiation zones of numerous outflow channels (Fig. 1b). The subsided terrains include regionally extensive networks of broad valleys (e.g., Fig. 1b,c) that are characterized by faulted margins (Fig. 1c–e) and abrupt breaks-in-slope (Fig. 1c–e) that deform pre-existing landforms (e.g., Fig. 1d,e). These formational structures have been interpreted as synclinal and monoclinal folds and associated ruptures developed by subsidence over caverns that formed by the removal of ice, water, and fluidized sediment12,13.

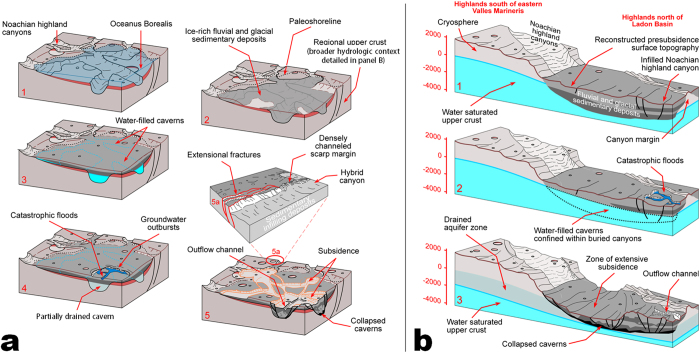

The southern Margaritifer Terra highlands are extensively dissected by vast canyon systems (Fig. 1b and 2a), which exhibit flanks densely marked by channels (e.g., Fig. 2b)4. The formation of these canyons is thought to have been dominated by Middle and Late Noachian fluvial erosion4. Late Noachian equatorial glaciers may have also contributed to their development23. Within the study region, these canyons converge northwestward into the highlands containing the subsided terrains (Fig. 1a,b). Although the contact between these two terrain types is disrupted by the Margaritifer and Iani chaotic terrains, we have identified a relatively narrow stretch of plateau materials that includes a subset of canyons that exhibit transitional morphologies (Fig. 2a). These hybrid canyons include scarp margins marked by dense channel systems and extensional fractures generated by subsidence (Fig. 2c,d), thus offering a rare insight into the regional upper stratigraphy of the outflow channel source region, consistent with the existence of buried canyons underlying the subsided valleys. Similar hybrid morphologies are observable along the flanks of Ladon basin (Fig. 1a), which constitutes large impact basin that partly captured drainage from the upland fluvial canyons (Fig. 1b).

Figure 2.

(a) Map showing the distribution of hybrid canyons in terrains located along the boundary between upland fluvial canyons and subsided valleys (context and location in Fig. 1b). (b) Topographic view of an upland fluvial canyon, which shows margins densely marked by small valleys/channels (black arrows). (c,d) Topographic views of a subsided valley (white arrow) that extends eastward to join a hybrid canyon that exhibits a margin dissected by small valleys/channels adjoined by subsidence related fractures (black arrow). We produced the map in this figure using Esri’s ArcGIS geographic information system.

The terrain contact between the upland and hybrid canyons is defined by elevations ranging between −2050 m and −1900 m (Fig. 3a, label 1), which also mark a section of the dichotomy boundary to the west (Fig. 3a, label 2). The dichotomy boundary corresponds approximately to the margins of water bodies (“Oceanus Borealis”24) that episodically covered the northern plains, most extensively during the Late Noachian24,25,26,27,28 and Late Hesperian25,26,27,28,29. The mean elevation of the Late Noachian ocean shoreline, which is the one of relevance to this study, has been estimated to be approximately −1680 m24. The elevation range also characterizes the inter-crater plains surfaces in western Arabia Terra (Fig. 3a, label 3), a region of the planet which has been interpreted as a frozen, buried remnant of the Late Noachian ocean30, where localized desiccation of the regional hydrosphere generated the widespread evaporite deposits detected by the Opportunity rover31.

Figure 3.

(a) Topographic view of circum-Chryse and western Arabia Terra showing the distribution of upland fluvial canyons (green), hybrid canyons (white) and subsided valleys (red). The black areas mark elevations ranging from −2050 to −1900, which mark the contact between the upland fluvial canyons and the subsided terrains (1), the dichotomy boundary west of the outflow channels (2), and the inter-crater plains of western Arabia Terra (3). (b) Reconstruction of coastal line at approximately −1900 m during the proposed stage of regional Late Noachian sedimentation. Question marks show the locations of uncertain paleoshoreline stretches. We produced the maps in this figure using Esri’s ArcGIS geographic information system.

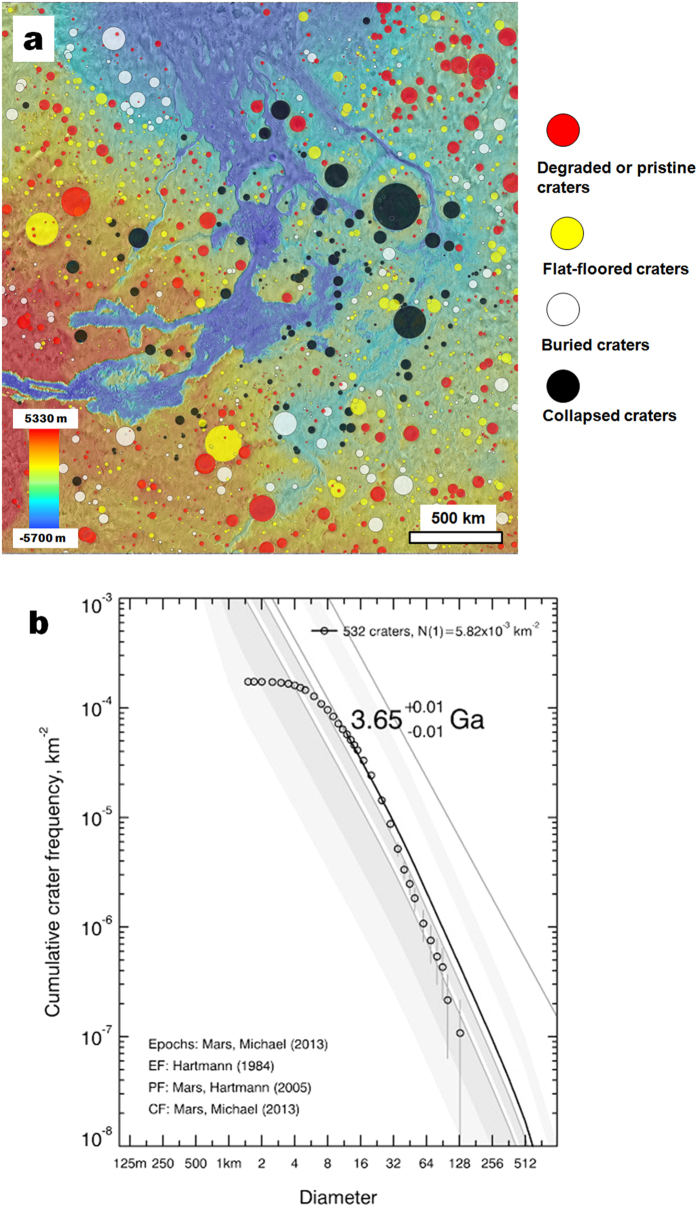

We propose the following regional geologic reconstruction leading to the development of the OFCS aquifers: The vast fluvial, or glacial-glaciofluvial, canyon systems of southern Margaritifer Terra4,23 discharged enormous volumes of sediments into southern circum-Chryse, where lower portions of these canyons were completely buried and integrated into the regional upper crustal stratigraphy (Fig. 4a). Coeval fluvial activity through the huge Uzboi-Ladon-Morava channel system, which connects the Argyre basin to the northern plains, is thought to have discharged vast volumes of water generated by the melting of a Late Noachian south polar ice sheet32. This enormous fluvial system could have also contributed to regional sedimentation in southern circum-Chryse2,33. In the proposed geologic scenario the upper extent of regional sedimentation would have been controlled by the elevation of Oceanus Borealis (Fig. 3b, sketches 1 and 2 in Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) Sketches depicting the inferred geologic evolution of a subsided highland plateau in southern circum-Chryse. (1) Submarine troughs become infilled with water-saturated sediments during the Late Noachian. (2) The sedimentary deposits freeze into permafrost upon the ocean’s retreat stage. (3) The troughs’ infilling deposits undergo melting to generate vast systems of interconnected water-filled caverns that extend to eastern Valles Marineris. (4) Groundwater outbursts lead catastrophic flooding. (5) Subsidence occurs over the evacuated caverns and hydrid canyons form close to the paleoshoreline elevation. (5a) View of a hybrid canyon. (b) Sketches depicting the inferred relationship between the eastern Valles Marineris, zones of subsidence and outflow channel formation in southern circum-Chryse. Ice/water-saturated sediments contained within buried troughs (1) undergo extensive melting and interconnect with a highly pressurized aquifer in eastern Valles Marineris (2). Extensive groundwater drainage along the trough interior deposits leads to outflow channel activity in southern circum-Chryse as well as to extensive subsidence over evacuated conduits (3). The pre- and post-subsidence surface elevations were constructed using MOLA elevation profiles and the topographic analyses described in the supplement. We produced the sketches using adobe illustrator.

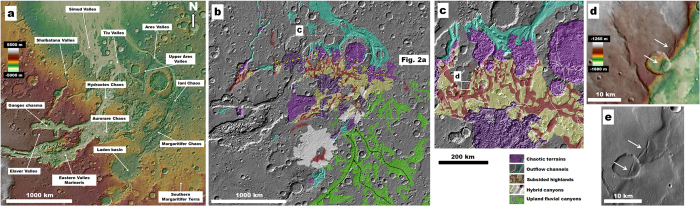

We infer a relatively short-lasting duration for the conditions allowing deep upland erosion connected with the formation of the proposed massive clastic sedimentary wedge based on previous investigations that propose a major spike in erosional and sedimentation rates occurring near the Noachian-Hesperian boundary34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. This geologic stage likely lasted just a few million years35. To establish a relative chronology for the proposed stage of large-scale sedimentation, we mapped the distribution of (1) collapsed craters, (2) buried craters, (3) flat-floored impact craters infilled up to their rims, and (4) impact craters that retain significant topography (Fig. 5a). Our mapping of buried craters is based on the identification of quasi-circular depressions distributed throughout the regional highlands. These features are thought to have formed by compaction of sediments overlying buried impact craters44. Impact crater statistics yield a Late Noachian age of 3.65 ± 0.01 Ga (Fig. 5b), and point to a major spike in impact cratering rates during this time period. This spike was likely the result of a late phase of the Late Heavy Bombardment thought to have affected Mars up to 3.6 Ga45. Increased global erosional and depositional rates associated with an active surface hydrosphere34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 during the Late Heavy Bombardment are consistent with impact-induced climate change as proposed by Segura et al.46.

Figure 5.

(a) Distribution of impact craters greater than 12 km in diameter. Measured impact craters include (1) collapsed craters, (2) buried craters, (3) flat-floored craters infilled up to their rims, and (4) degraded and pristine craters that retain significant topography. (b) Cumulative size-frequency distribution for all craters in study region. Calculated age includes craters with diameters larger than 12 km. Crater diameters were measured in ArcGIS software and cumulative size-frequency distributions were plotted using Craterstats2 software59. The Hartmann60 model production function and the Michael59 chronology function were used to calculate an overall age of 3.65 ± 0.01 Ga for the sedimentary wedge (i.e., Late Noachian60).

The rapid groundwater evacuation required to generate the Late Hesperian catastrophic floods would have required groundwater migration via extraordinarily permeable structures, most likely including extensive systems of large interconnected caverns filled with water and/or unconsolidated fluidizable sediment12,13. We estimate that ~2.8 × 105 km3 of groundwater and eroded or fluidized sediments were rapidly evacuated from the hypothesized caverns. This value was calculated as the total area of subsided highlands (~4 × 105 km2) times an average negative relief of ~700 m [−1200 m minus −1900 m, respectively, elevation averages of undeformed highland plateaus and adjoining subsided terrains (Supplement)].

The distribution of the subsided valleys, here proposed to have been largely controlled by the distribution of the ancient buried troughs, indicates that the hypothesized caverns formed a direct connection between eastern Valles Marineris and a lower-lying equatorial belt of chaotic terrains located at the upstream portions of numerous outflow channels (dashed yellow line in Fig. 1a). These chaotic terrains occur within highland surfaces located within a narrow range of surface elevations (approx. ~500 m to −1000 m), which is consistent with groundwater outbursts produced by rapid release from an initially confined, underground body of water conforming to a potentiometric surface defined by the upper boundary of groundwater saturated crust in eastern Valles Marineris. Vast aquifers confined beneath a seal of ice-cemented permafrost are proposed to have existed within eastern Valles Marineris and nearby plateau regions during the Late Hesperian47,48,49. These aquifers are thought to have reached superlithostatic pressures as a consequence of ~3.5 to ~4.5 kilometers of hydraulic head generated due to the warping of regional upper crustal rocks by the Tharis uplift19.

Elaver Valles (Fig. 1a), located at an elevation of ~2000 m, is the highest outflow channel in eastern Valles Marineris. In contrast, the northern margin of the subsided terrain adjoining upper Ares Valles exhibits elevation ranges between approximately −1500 and −2500 m (Supplement). Moreover, elevation profiles from nearby undeformed highland surfaces show that the pre-subsidence topography was likely closer to approximately −1200 m, ranging between approximately −500 m and −1500 m (Supplement). These relief estimates provide a basis to quantify relevant hydraulic pressures. Prior to the catastrophic outflows, hydrostatic pressures within the confined, water-filled caverns could have attained hwgρ between ~13 and 16.5 MPa (or 11 MPa, if corrected to pre-subsidence topography hw (~3000 m)), where hw is the relief in meters (~3500 m to ~4500 m), g is Martian surface gravity (3.711 m/s2), ρ is water density (1000 kg/m3). These estimates of regional groundwater pressurization approximate or exceed the upper estimate predicted to have caused outflow channel activity in circum-Chryse [10 MPa]50. The pressure may have been even greater if the groundwater was highly saline, saturated in CO2, or contained large volumes of fine-grained sediments. Following the groundwater outbursts, the hydraulic head within the previously confined cavernous water systems would have rapidly diminished due to drawdown of the regional water table, however, continued exsolution of CO2 could have maintained the outflow channel discharges.

Our proposed scenario implies that the sedimentary deposits that buried the troughs were highly porous and likely included large volumes of hydrated clays and perhaps glacal ice. As Oceanus Borealis receded, these water-saturated deposits would have progressively frozen into extensive areas of ice-rich permafrost (Fig. 4a, sketch 2), which remained stable for a few hundred million years.

Subsequent Late Hesperian groundwater eruptions and subsidence would have been controlled by the distribution of the buried troughs (Fig. 4a, sketches 3–5). Consequently, the water-filled caverns that produced the immense outflow channel discharges and related subsidence12,13 must have been excavated within the troughs’ permafrost or water-saturated infill. The generation and integration of these caverns have been attributed to localized permafrost melting by magmatic dikes in a way that large groundwater bodies were generated and confined by surrounding icy Late Noachian strata12,13,21, which likely contained significant volumes of less permeable phyllosilicates23. The integration of these caverns and their connection to a kilometers-deep aquifer system in Valles Marineris47,48,49 would have allowed for the role of superlithostatic pressures (Fig. 4b) in driving immense discharges to the southern Chryse basin. An alternative scenario might also involve the pressurization of meltwater beneath the Valles Marineris ice sheet51.

We find that Southern circum-Chryse had a unique geologic history that combined large-scale fluvial sedimentation along the margin of an ancient Late Noachian ocean; conduit development within the sedimentary materials infilling vast systems of buried troughs; and the development of superlithostatic pressures within the lower reaches of these conduits, perhaps driven by elevated potentiometric surfaces transferred from eastern Valles Marineris. High hydraulic pressure gradients across large regions of water-filled caverns permitted the rapid drainage of the immense groundwater systems. This region of the planet contains the largest outflow channel system on Mars, so our hypothesis, including the precursory erosional and sedimentation processes, centers on one of the most dramatic hydrogeologic stories in the Solar System.

On Mars there is evidence for the long-term retention of large groundwater volumes within buried impact craters12,52 and within thick upper crustal hydrated mineral deposits53. Clastic wedges containing large amounts of relic massive ice have been recognized within relatively young Earth deposits emplaced during recent glacial periods. These include glacial and glaciomarine sedimentary sequences54,55,56,57 produced during high sea-level stands58 that infilled and buried older valleys excavated by glacial and glaciofluvial erosion54,55,56,57. However, frequent warm climatic excursions on Earth imply that these ice masses can only remain stable over relatively short geologic periods. On the other hand, the colder climate and lower geothermal heat flow on Mars could have allowed Martian clastic wedges to retain vast volumes of ice during billions of years. This model and our new observations provide support for the Martian primeval ocean24,25,26,27,28 and link the formation of the vast outflow channel source region aquifers to the emplacement of thick water-rich upper crustal sedimentary deposits during a spike in global hydrologic activity34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. The spike was perhaps triggered by impact-induced climate change46 during a late phase of the Late Heavy Bombardment45. If these extensive Late Noachian aquifer systems formed globally, then their development could have significantly depleted the surface hydrosphere, thereby playing a potentially significant role in triggering the abrupt transition into the colder and drier conditions that characterized most of the post-Noachian climatic regimes1. Thus, global Late Noachian sedimentary infill of buried canyons and craters might still retain much of the planet’s hydrosphere.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Rodriguez, J. A. P. et al. Martian outflow channels: How did their source aquifers form, and why did they drain so rapidly? Sci. Rep. 5, 13404; doi: 10.1038/srep13404 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to James Head III for his insightful comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of this manuscript. Funding provided by NASA’s NPP program to J. Alexis P. Rodriguez and by MRO HiRISE Co-Investigator funds to V.C. Gulick. A. G. Fairén was supported by the Project “icyMARS”, funded by the European Research Council, Starting Grant no 307496. Hideaki Miyamoto was supported by KAKENHI 23340126. We would also like to express our gratitude to Alexander Cox for his helpful suggestions regarding the editing of this paper. HiRISE images were analyzed using HiView developed by the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.A.P.R., J.S.K., V.R.B. and V.C.G. wrote the main text, J.A.P.R. prepared figures 1, 2 and 3 and the supplement. D.C.B. prepared figure 4, R.L. and M.Z. prepared figure 5. A.G.F., Y.J., H.M. and N.G. contributed to the development of specific aspects of the proposed hypotheses. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Clifford S. M. A model for the hydrologic and climatic behavior of water on Mars. Jour. of Geophys. Res 98, 10973–11016 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Clifford S. M. & Parker T. J. The evolution of the martian hydrosphere: Implications for the fate of a primordial ocean and the current state of the northern plains. Icarus 154, 40–79 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Baker V. R. The channels of Mars (University of Texas Press, 1982). [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. L. et al. Geologic map of Mars: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3292, scale 1:20,000,000, http://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/3292/ (2014) Date of access: 0707/2015.

- Scott D. H. & Carr M. H. Geologic map of Mars: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map I-1083, scale 1:25,000,000, http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/i1083 (1978) Date of access: 0707/2015.

- Harrison K. P. & Grimm R. E. Regionally compartmented groundwater flow on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 114, E04004 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Russell P. S. & Head J. W. The Martian hydrologic system: Multiple recharge centers at large volcanic provinces and the contribution of snowmelt to outflow channel activity. Planet. Space Sci., Planet Mars II 55, 315–332 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Carr M. H. Elevations of water-worn features on Mars: Implications for circulation of groundwater. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 5131 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Harrison K. P. & Grimm R. E. Tharsis recharge: A source of groundwater for Martian outflow channels. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31 (2004), 10.1029/2004GL020502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malin M. C. & Edgett K. S. Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbiter Camera: Interplanetary cruise through primary mission. J. Geophys. Res. 106 (E10), 23, 429–423,570 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Frey H. V. Impact constraints on, and a chronology for, major events in early Mars history. J. Geophys. Res. 111 (2006), 10.1029/2005JE002449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J. A. P. et al. Control of impact crater fracture systems on subsurface hydrology, ground subsidence, and collapse, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 110 (2005), 10.1029/2004JE002365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J. A. P. et al. Outflow channel sources, reactivation, and chaos formation, Xanthe Terra, Mars. Icarus 175, 36–57 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lucchitta B. K. et al. in Mars (Eds. Kieffer H. H., Jakosky B. M., Synder C. W., Mattews S. M.), 453–492, (Univ. of Ariz. Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J. F. et al. Preliminary Mariner 9 report on the geology of Mars. Icarus 17, 289–327 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. H. & Tanaka K. L. Geologic map of the western equatorial region of Mars, U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map I-1802-A, scale 1:15,000,000, ISBN: 978-0-607-89775-3, http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/i1802A (1986) Date of access: 0707/2015.

- Sharp R. P. & Malin M. C. Channels on Mars. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull 86, 593–609 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- Baker V. R. & Milton D. J. Erosion by catastrophic floods on Mars and Earth. Icarus 23, 27–41 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Carr M. J. Formation of Martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. 84, 2995–3007 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Carr M. H. Water on Mars (Oxford University Press, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J. A. P., Sasaki S. & Miyamoto H. Nature and hydrological relevance of the Shalbatana complex underground cavernous system. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1304 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Rotto S. & Tanaka K. L. Geologic/geomorphic map of the Chryse Planitia Region of Mars Geologic map of the western equatorial region of Mars, U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map, I-2441-A, scale 1: 5,000,000, http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/i2441 (1995) Date of access: 0707/2015.

- Fairén A. G., Davila A. F., Schulze-Makuch D., Rodríguez J. A. P. & McKay C. P. Glacial paleoenvironments on Mars revealed by the paucity of hydrated silicates in the Noachian crust of the northern lowlands. Planet. Space Sci. 70, 126–133 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Baker V. R. et al. Ancient oceans, ice sheets and the hydrological cycle on Mars. Nature 352, 589–594 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Head J. W. et al. Possible Ancient Oceans on Mars: Evidence from Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter Data. Science 286, 2134–2137 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker T. J., Saunders R. S. & Schneeberger D. M. Transitional morphology in west Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars: Implications for modification of the lowland/upland boundary. Icarus 82, 111–145 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Carr M. H. & Head J. W. Oceans on Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 5042 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Fairén A. G. et al. Episodic flood inundations of the northern plains of Mars. Icarus, 165, 53–67 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Kreslavsky M. A. & Head J. W. Fate of outflow channel effluent in the northern lowlands of Mars: The Vastitas Borealis Formation as a sublimation residue from frozen ponded bodies of water. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 5121 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Lucchitta B. K. Ice in the northern plains: relic of a frozen ocean? Workshop on the Martian northern plains : sedimentological, periglacial, and paleoclimatic evolution. edited by Kargel J. S., Parker T. J. & Moore J. M., pp 9–10 Lunar and Planetary Inst. Tech. Rep 93-04 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Zabrusky K., Andrews-Hanna J. C. & Wiseman S. M. Reconstrucing the distribution and depositional history of the sedimentary deposits of Arabia Terra, Mars. Icarus 220, 311–330 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Fastook J. L., Head J. W., Marchant D. R., Forget F. & Madelaine J. B. Early Mars climate near the Noachian-Hesperian boundary: Independent evidence for cold conditions from basal melting of the south polar ice sheet (Dorsa Argentina Formation) and implications for valley network formation. Icarus 219, 25–40 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Parker T. J. & Gorsline D. S. Where is the source for Uzboi Vallis, Mars? Lunar Planet Sci. XXII, 1033–1034 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Irwin R. P. III et al. An intense terminal epoch of widespread fluvial activity on early Mars: Increased runoff and paleolake development. J. Geophys. Res. 110 (E12S15) (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kite E. S. Lucas A. & Fassett C. I. Pacing Early Mars fluvial activity at Aeolis Dorsa: Implications for Mars Science Laboratory observations at Gale Crater and Aeolis Mons. Icarus 225, 850–855 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart C. J. et al. Long-term precipitation and late-stage valley network formation: landform simulations of Parana Basin, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 114 (E01003) (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hoke M. R. T. et al. Formation timescales of large Martian valley networks. Earth and Planet. Sci. Lett. 312, 1–12 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Stepinski T. F., Stepinski A. P. Morphology of drainage basins as an indicator of climate on early Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 110 (E12S12) (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Fassett C. I. & Head J. W. The timing of Martian valley network activity: constraints from buffered crater counting. Icarus 195, 61–89 (2008a). [Google Scholar]

- Fassett C. I. & Head J. W., Valley network-fed, open-basin lakes on Mars: distribution and implications for Noachian surface and subsurface hydrology. Icarus 198, 37–56 (2008b). [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart C. J. et al. Long-term precipitation and late-stage valley network formation: landform simulations of Parana Basin, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 114 (E01003) (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Som S. M. et al. Scaling relations for large Martian valleys. J. Geophys. Res. 114 (E02005) (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tosca N. J. & Knoll A. H. Juvenile chemical sediments and the long term persistence of water at the surface of Mars. Earth and Planet. Sci. Lett. 286, 379–386 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowski D. L., Frey H. V., Roark J. H. & McGill G. E. Buried impact craters: A topographic analysis of quasi-circular depressions, Utopia Basin, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 110 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Cuk M. Chronology and sources of lunar impact bombardment. Icarus 218, 69–79 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Segura T. L. et al. Environmental Effects of Large Impacts on Mars. Science 298, 1977–1980 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman N. M. & Baker V. R. in Megaflooding on Earth and Mars (eds Burr D. M., Baker V. R. & Carling P. A. ) 172–193 (Cambridge University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu G. et al. Paleolakes, paleofloods, and depressions in Aurorae and Ophir Plana, Mars: Connectivity of surface and subsurface hydrological systems. Icarus 201, 474–491 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Coleman N. M. Hydrographs of a Martian flood from a breached crater lake, with insights about flow calculations, channel erosion rates, and chasma growth. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 263–277 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna J. C. & Phillips R. J. Hydrological modeling of outflow channels and chaos regions on Mars. J Geophys. Res. 112 (2007), 10.1029/2006JE002881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gourronc M. et al. One million cubic kilometers of fossil ice in Valles Marineris: Relicts of a 3.5 Gy old glacial land system along the Martian equator. Geomorphology 204, 235–255 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zegers T. E., Oosthoek J. H. P., Rossic A. P., Blomd J. K. & Schumachere S. Melt and collapse of buried water ice: An alternative hypothesis for the formation of chaotic terrains on Mars. Earth and Planet. Sci. Lett. 297, 496–504 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Mustard J. F., Poulet F., Ehlman B. E., Milliken R. & Fraeman A. Sequestration of volatiles in the Martian crust through hydrated minerals: A significant planetary reservoir of water. Lunar Planet Sci. XLIII, 1539 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Vorren T. O. & Laberg J. S. Trough mouth fans—Palaeoclimate and ice-sheet monitors. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 16, 865–881 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Olsen L., Sveian H., Ottesen D. & Rise L. Quaternary glacial, interglacial and interstadial deposits of Norway and adjacent onshore and offshore areas. In Olsen L., Fredin O. & Olesen O. (eds.) Quaternary Geology of Norway, Geological Survey of Norway Special Publication 13, 79–144 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan R. P. M. Quaternary landform and sediment analysis of the Alliston area (southern Simcoe County), Ontario, Canada. M.S. Thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, 178 pp (2013).

- Girard F., Ghienne J. F. & Rubino J. L. Channelized sandstone bodies (‘cordons’) in the Tassili N’Ajjer (Algeria and Libya): Snapshots of a late Ordovician proglacial outwash plain. In Huuse M., Redfern J., Le Heron D. P., Dixon R. J., Moscariello A. & Craig J. (eds.) Glaciogenic Reservoirs and Hydrocarbon Systems Geological Society [London] Special Publication 368, 355–379 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Polyak L. & Jakobsson M. Quaternary sedimentation in the Arctic Ocean: Recent advances and further challenges. Oceanography 24, 52–64 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Michael G. G., Planetary surface dating from crater size-frequency distribution measurements: Multiple resurfacing episodes and differential isochron fitting. Icarus 226, 885–890 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann W. K. Martian cratering. 8. Isochron refinement and the history of martian geologic activity. Icarus 174, 294–320 (2005). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.