Introduction

A 35-year-old male presented with a three-day history of epigastric pain and vomiting. Six months prior to presentation, the patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus and was on an insulin therapy regimen. He had no relevant history of familial illness. He reported 20 years of chronic, heavy alcohol consumption. Physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness. Laboratory investigation revealed raised serum amylase and serum pancreatic lipase levels (516 U/L and 912 U/L; normal values 0–200 U/L and 0–190 U/L, respectively), consistent with pancreatitis. Ultrasonography revealed mild peripancreatic oedema, and the body and tail of pancreas could not be visualized. A contrast-enhanced abdominal computed axial tomography (CT) examination allowed for only partial visualization of the pancreas. The pancreatic head and uncinate process were normal, but the distal neck, body, and tail of the pancreas were absent. The stomach and loops of jejunum could be seen in the distal pancreatic bed (dependent stomach/dependent intestine sign, see Figures 1 and 2), suggesting agenesis of the dorsal pancreas (ADP) as a possible diagnosis. To confirm the diagnosis, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed. On MRCP, the dorsal pancreatic duct (duct of Santorini) and minor duodenal papilla could not be visualized. The common bile duct and ventral duct of Wirsung were normal and clearly seen (Figure 3). These findings were compatible with complete dorsal pancreatic agenesis, eliminating the need for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The patient was managed conservatively with low-fat dietery modification.

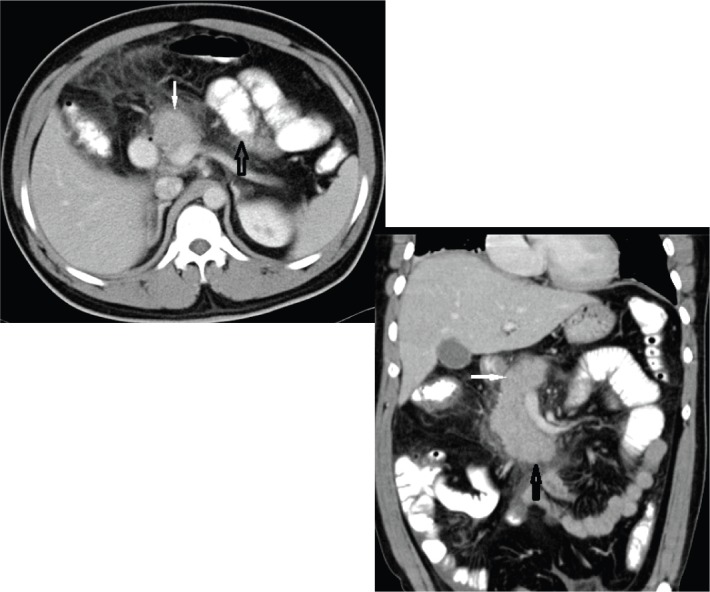

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) [ Fig. 1(a)] and coronal CT [Fig. 1(b)] showing normal head (white solid arrow) and uncinate process (black solid arrow) with absence of distal neck, body and tail of the pancreas. Jejunal loops of small intestine (hollow black arrow) and stomach in the distal pancreatic bed can be seen (dependent stomach/dependent intestine sign).

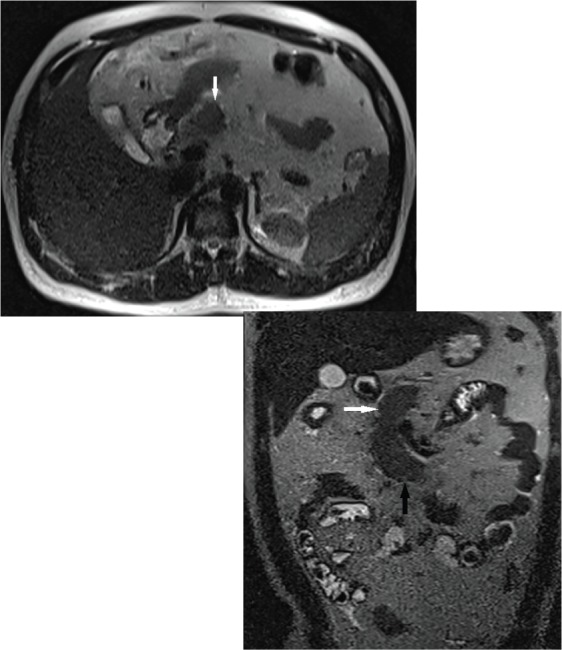

Figure 2.

Axial T2W magnetic resonance (MR) [ Fig. 2(a)] and coronal T2W MR [ Fig. 2(b)] images showing partial visualization of the pancreas. Well-developed, normal head (white solid arrow) and uncinate process (black solid arrow) of pancreas are visible, but the neck, body, tail and dorsal pancreatic duct cannot be seen.

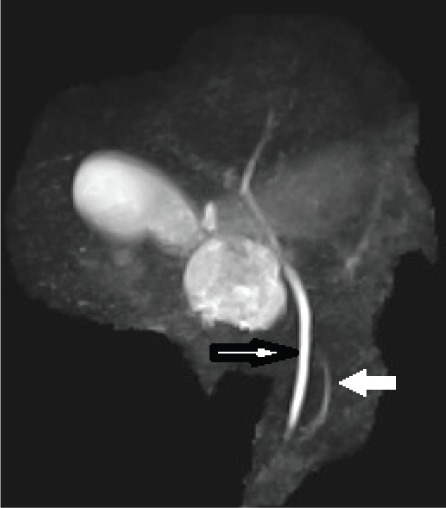

Figure 3.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) image showing a normal common bile duct (black bordered arrow) and duct of Wirsung (white solid arrow). The duct of Santorini is not visualized.

Discussion

The pancreas develops from dorsal and ventral buds originating from the endodermal lining of the duodenum. During the seventh gestational week, the ventral bud turns posteriorly and to the left, connecting with the dorsal bud to form the mature gland. Each of the pancreatic buds grows into a pair of branching arborized ductal systems. The neck, body, tail, and cephalic aspects of the head of the pancreas originate from the dorsal bud. This part is drained through duct of Santorini. At the 12th week of embryogenesis, discrete islets of Langerhans form primarily within the tail of the pancreas and the dorsal pancreas. The ventral bud becomes the inferior portion of the head and the uncinate process, which is drained through duct of Wirsung1,2. Abnormal embryogenesis can lead to developmental failure of the dorsal pancreas, resulting in complete agenesis of the dorsal pancreas3.

This condition is exceedingly rare; less than 100 cases have been reported in the literature since 19114. Agenesis of the ventral pancreas and complete agenesis of the pancreas are incompatible with life5. The exact mechanism and aetiology of ADP is not known.

Most ADP patients are asymptomatic, but 92.9% of the symptomatic cases present with epigastric pain. About half of affected individuals develop diabetes mellitus, resulting from reduced islet cell mass secondary to the absence of endocrine structures, which are normally predominantly located in the body and tail of the pancreas. Pancreatitis results from sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, compensatory enzyme hypersecretion and consequent hypertrophy of the remnant ventral gland, and higher intrapancreatic duct pressures resulting from morphological alterations6–8. Our patient's epigastric pain, pancreatitis, and diabetes mellitus can all be explained as resulting from ADP.

Other abnormalities such as heterotaxy, polysplenia syndrome, ectopic spleen, bowel malrotation, coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, atrioventricular valvular abnormalities, and total anomalous pulmonary venous connection have also been reported to be associated with ADP6.

Conditions that have clinical pictures similar to that of agenesis of the dorsal pancreas include: pseudoagenesis (atrophy of the corpus and the tail of the pancreas secondary to chronic pancreatitis); carcinoma of the head of pancreas (proximal atrophy of the gland); pancreas divisum (absence of fusion or incomplete fusion of the ventral and dorsal pancreas, mainly of the drainage ducts [Wirsung' and Santorini]); pancreatic pseudolipodystrophy; pancreatic masses; and distal pancreatic lipomatosis (abundant fat tissue anterior to the splenic vein, with a present dorsal pancreatic duct)9–12. It is essential to differentiate these conditions from ADP, so it is therefore crucial to obtain a careful medical history and to perform the appropriate imaging studies: ultrasonography, computed axial tomography (CT), magnetic resonance pancreatogram (MRI, including MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and—a recent addition—endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in order to exclude the aforementioned differential diagnoses.

Previously, the diagnosis of ADP was only made at autopsy or median laparotomy with a xipho-umbilical approach. ERCP is considered to be the gold standard for detailed description and evaluation of the biliary and pancreatic tree because of its superior spatial resolution . However, the examination is invasive, technique-sensitive, operator-dependent, requires radiation exposure and morbidity risk (pancreatitis can result from catheterization of the minor duodenal papilla). The ultrasonographic appearance of ADP exhibits the head of pancreas as a small hypoechoic structure just ventral to the portal confluence. At the junction of head and neck of pancreas, a hyperechoic line of demarcation segregates the hypoechoic pancreatic head from the more echogenic retroperitoneal fat13–14. However, diagnostic findings on transabdominal ultrasound can be suspicious because of organ screening and overlying bowel gas interference, as occurred in our case. Three-dimensional reconstruction CT is a better method for ADP diagnosis because it allows for visualization of the viscera blood supply. In a study by Karcaaltincaba, multidetector CT (MDCT) was performed to differentiate of ADP from distal or dorsal pancreas lipomatosis9. Agenesis of the dorsal pancreas can be diagnosed by the absence of body and tail of the pancreas. In the absence of the distal pancreas, the distal pancreatic bed can be filled by stomach or intestine (dependent stomach or dependent intestine signs), which abut the splenic vein. The same findings can be seen in patients who have undergone a distal pancreatectomy, but in these patients the splenic vein is absent. In the case of distal pancreatic lipomatosis, abundant fat tissue is observed anterior to the splenic vein. Dependent stomach and/or dependent intestine signs on MDCT imaging can thus allow confirmation of ADP9.

When the concern is merely diagnostic , magnetic resonance imaging, including MRCP, is the choice of investigation for confirmation, as it is non-invasive and accurately depicts the pancreatic duct morphology and parenchyma in the same examination. In a study reported by Kahl et al., endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was described as a relatively new minimally invasive imaging technique which provides direct visualization of the entire pancreatic parenchyma and the pancreatic ductal system13. EUS also provides the opportunity for fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and may be as good as ERCP13,14. EUS is crucial in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma but further studies are recommended to confirm its diagnostic efficacy.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest and no funding.

References

- 1.Macari M, Giovanniello G, Blair L, et al. Diagnosis of agenesis of thedorsal pancreas with MR pancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:144–146. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.1.9423620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulusan S, Bal N, Kizilkilic O, Bolat F, Yildirim S, Yildirim T, et al. Case report: solid-pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas associated with dorsal agenesis. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:441–443. doi: 10.1259/bjr/91312352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulte SJ. Embryology, normal variation, and congenital anomalies of the pancreas. In: Freeny PC, Stevenson OW, editors. Margulis and Burhenne 's alimentary tract radiology. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Yearbook; 1994. pp. 1039–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohapatra M, Mishra S, Dalai PC, Acharya SD, Nahak B, Ibrarullah M, et al. Imaging Findings in Agenesis of the Dorsal Pancreas. Report of Three Cases. JOP. 2012;10:108–114. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voldsgaard P, Kryger-Baggesen N, Lisse I. Agenesis of pancreas. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:791–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnedl WJ, Piswanger-Soelkner C, Wallner SJ, Krause R, Lipp RW, Hohmeier HE. Agenesis of the dorsal pancreas and associated diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:481–487. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cano DA, Hebrok M. Pancreatic development and disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:745–762. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uygur-Bayramiçli O, Dabak R, Kiliçoglu G, Dolapçioglu C, Oztas D. Dorsal Pancreatic Agenesis. JOP. 2007;8:450–452. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karcaaltincaba M. CT differentiation of distal pancreas fat replacement and distal pancreas agenesis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28:637–641. doi: 10.1007/s00276-006-0151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi R, Kumar R, Bhargava S, Rastogi V. Isolated pancreatic hypoplasia: a rare but significant radiological finding. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:289–290. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.56090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfgang J, Schnedl WJ, Reisinger EC, Scheiber P, Pieber TR, Lipp RW, et al. Complete and partial agenesis of the dorsal pancreas within one family. Gatrointest Endosc. 1995;42:485–487. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radi JM, Gaubert R, Cristol-Gaubert R, Baecker V, Travo P, Prudhomme M. A 3D reconstruction of pancreas development in the human embryos during embryonic period (Carnegie stages 15–23) Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32:11–15. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahl S, Glasbrenner B, Zimmermann S, Malfertheiner P. Endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatic diseases. Dig Dis. 2002;20:120–126. doi: 10.1159/000067481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palazzo L. Echoendoscopy of the pancreas. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;25:26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5705(02)70237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]