Abstract

Background:

Transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs) are one of the biggest threats to blood transfusion safety. Nucleic acid testing (NAT) in blood donor screening has been implemented in many countries to reduce the risk of TTIs. NAT shortens this window period, thereby offering blood centers a much higher sensitivity for detecting viral infections.

Aims:

The objective was to assess the role of individual donor-NAT (ID-NAT) for human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and its role in blood safety.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 32978 donations were tested for all three viruses using enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay (Vironostika® HIV Ag-Ab, Hepanostika® HCV ultra and hepatitis B surface antigen ultra by Biomerieux) and ID-NAT using Procleix Ultrio plus® Assay (Novartis Diagnostic, USA). All initial NAT reactive samples and serology nonreactive were retested in triplicate and NAT discriminatory assay for HIV-1, HCV and HBV were performed.

Results:

Of the 32978 samples, 43 (0.13%) were found to be ID-NAT reactive but seronegative. Out of 43, one for HIV-1, 13 for HCV and 27 for HBV were reactive by discriminatory assays. There were two samples that were reactive for both HCV-HBV and counted as HCV-HBV co-infection NAT yield. The prevalence of these viruses in our sample, tested by ID-NAT is 0.06%, 0.71%, and 0.63% for HIV-1, HCV and HBV respectively. The combined NAT yield among blood donors was 1 in 753.

Conclusion:

ID-NAT testing for HIV-1, HCV and HBV can tremendously improve the efficacy of screening for protecting blood recipient from TTIs. It enables detection of these viruses that were undetected by serological test and thus helped in providing safe blood to the patients.

Keywords: Blood safety, hepatitis B and C virus, individual donor-nucleic acid testing

Introduction

Blood safety status in India is challenging task with a population of more than 1.2 billion, including more than 2.5 million, 15 million, 43 million cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV),[1,2] with a seroprevalence of HIV, HCV and HBV in blood donors, which is 0.5, 0.4 and 1.4% respectively,[3] compared to 0.0097, 0.3 and 0.07% in the US blood donors respectively.[4]

Despite the current practice of screening blood with the newest generation serological tests of different sensitivities, a considerable residual risk of transfusion transmission of this virus remains. Although these tests have shortened the pre-sero conversion window period, they still are not able to identify a number of newly infected blood donors.[5] This technologic limitation puts recipients at a tangible, albeit infrequent risk for transmissible disease. Since viremia precedes sero conversion by several days in case of HIV and several weeks for HBV and HCV, tests that detect viral nucleic acid are considered a significant step in our quest to achieve the goal of zero risks for blood transfusion recipients.[6]

Individual donor-nucleic acid amplification test (ID-NAT) has the potential to detect viremia earlier than current screening methods which are based on sero conversion. ID-NAT is currently being used in selected center for donor screening, though it is not mandatory by drugs and cosmetics rules. It is highly sensitive and a direct test, which detects the viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) by the amplification method. It reduces the window period by detecting low level of viral genomic materials that are present soon after infection but before the body starts producing antibodies in response to the virus. This allows for earlier detection of infection and further decrease the possibility of transmission via transfusion and also detects mutants and occult cases.[7]

Individual donor-NAT is currently used in conjunction with serological test in North America, Europe, Australia and Asia.[8] Although NAT screening cannot completely eliminate the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs), but it has reduced the risk of HIV-1, HCV and HBV where it has been implemented.[9] Implementation of NAT has introduced not only a new methodology, new logistic but when combined with sensitive serology it provides the most sensitive and specific screening platform for blood screening.[10] The window period for detection by ID-NAT by ultrio plus is 4.7 days for HIV-1, 2.2 days for HCV and 14.9 days for HBV.[11,12] The corresponding window periods for serological test are 15-20 days, 2-26 weeks and 50-150 days respectively.

The aim of this study is to assess the impact of the introduction of ID-NAT for HIV-1, HCV and HBV and its role in further improving blood safety in a tertiary care hospital.

Materials and Methods

Study design

All voluntary and replacement blood donors donating in the Department of Immunohematology and Blood Transfusion, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab between January and December 2013 were included in the study. Samples from the donated blood units were tested in our ID-NAT center.

Donor samples studies

From January to December 2013, a total of 32,978 blood donor's samples were tested by ID-NAT apart from routine serological screening for anti-HIV 1-2, p24 antigen, anti HCV and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) by Biomerieux (Vironostika® HIV Ag-Ab, Hepanostika® HCV ultra and HBsAg ultra, France). All the samples were tested individually by Procleix® Utrio Plus® Assay (Novartis Emeryville, CA). It is a transcription mediated amplification (TMA) based screening for the simultaneous, single tube detection of HIV-1, HCV RNA and HBV DNA in donor's plasma. The entire test takes place in a single tube and involves three steps

Target capture

Target amplification by TMA

Detection of the amplification products with chemiluminescent probes by the hybridization protection assay.

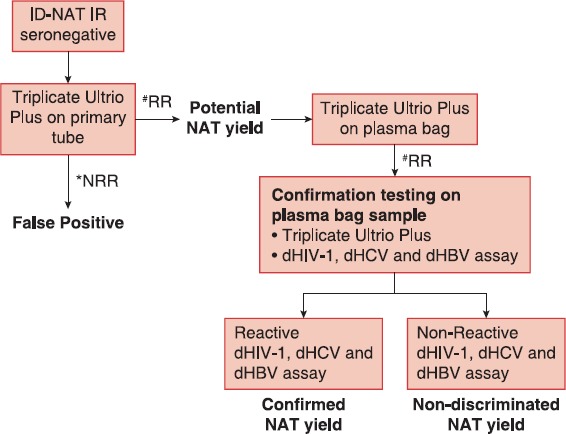

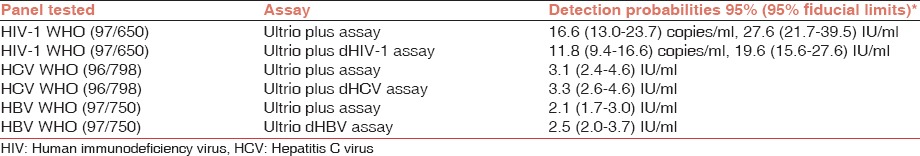

Finally, the dual kinetic assay simultaneously detects the internal control and the viral RNA or DNA. All three assays incorporate internal control to validate each reaction.[13,14] ID-NAT is a multiplex assay which provide simultaneous detection of HIV, HCV RNA and HBV DNA. Samples found initial reactive in the Utrio Plus Assay were later retested using multiplexed protocol as shown in Figure 1. ID Procleix® Ultrio Plus® Assay is a sensitive screening assay available. The analytic sensitivity of Procleix® Ultrio Plus® Assay (95% detection limit for routine testing) for HIV-1 27.6 IU/ml, HCV 3.1IU/ml and HBV 2.1 IU/ml,[15] which has been described in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Ultrio Plus screening algorithm in seronegative donations. #RR: Reactive repeat, *NRR: Non reactive repeat

Table 1.

Analytical sensitivity of Procleix® Ultrio Plus® assay

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using the Chi-square test.

Results

A total of 32978 blood units were collected over the period of 1 year. Of these 11592 (35.2%) were voluntary and 21386 (64.8%) were replacement donors. The majority of these 30217 (91.6%) were first time and lapsed donors, and remaining 2761 (8.4%) were regular repeat donors. There were 30319 (91.9%) males and 2659 (8.1%) females. Of these, there were 589 (1.78%) sero-reactive cases, including 40 (0.12%) anti HIV, 328 (0.99%) anti HCV and 221 (0.67%) HBsAg. All blood samples were tested by ID-NAT, in which 509 (1.54%) were initial reactive. Discriminatory assay found 20 (0.06%) to be reactive for HIV-1 RNA, 222 (0.67%) to be reactive for HCV RNA and 181(0.55%) for HBV DNA. Thirty seven (0.11%) were Ultrio Plus initial reactive, but negative in triplicate with primary tube and counted as false positive. Six samples were NAT initial reactive and also sero-reactive but discriminatory non-reactive and counted as seropositive, NAT-IR concordant positives non-discriminated.

Nucleic acid testing (NAT) yield: Of these 509 ID-NAT reactive samples, 43 (0.13%) were ID-NAT reactive, but seronegative. Out of 43, one was reactive for HIV-1, 13 for HCV and 27 for HBV. There were two samples that were reactive for both HCV-HBV and counted as HCV-HBV co-infection NAT yield. The prevalence of these viruses in our sample tested by ID-NAT is 0.06%, 0.71%, and 0.63% for HIV-1, HCV and HBV respectively. The combined NAT yield among blood donors was one in 753.

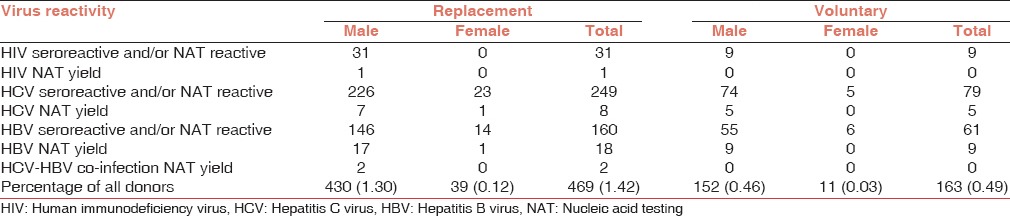

Sero yield: There were 166 (0.5%) samples, which were sero-reactive, but ID-NAT non-reactive which included 20 for anti-HIV, 106 for anti-HCV and 40 for HBsAg. The reactive rate among voluntary blood donors was 0.49% compared with 1.42% in replacement blood donors as shown in Table 2 and P ≥ 0.05, but this was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Characteristic distribution of reactive donor profile in replacement and voluntary donors

Discussion

The efficacy of the introduction of a new technology such as NAT to screen TTI's is measured by the incremental rate of detection of acute infection compared with conventional screening or more specifically by the reduction in viral transmission risk. Despite improvements in HIV, HCV and HBV serological tests in recent years, instances of viral transmission via transfusion still occur because of donation that take place in pre-sero conversion window phase, is infected with immune variant virus or is a non sero converting chronic carriers and it can lead to a 1% chance of transmission of TTIs with every unit of blood.[16]

In the present ID-NAT study which is first ever in Punjab, 32978 blood donors samples were tested, 43 were tested NAT reactive and were serologically non-reactive for any of the three viruses. Among these 43 NAT yield, 1 (1/32978) was reactive for HIV-1, 13 (1/2536) for HCV and 27 (1/1221) for HBV virus. There were two samples, which were reactive for both HCV-HBV and counted as HCV-HBV co-infection NAT yield. The prevalence of the three viruses in our study was 0.06%, 0.71% and 0.63% for HIV-1, HCV and HBV respectively. The combined NAT yield rate of ID-NAT among blood donors for all three viruses was one in 753 sample tested.

The NAT yield rate from other blood banks in India is 1 in 3182,[17] 1 in 2972,[18] 1 in 2622[7] and 1 in 1528[19] which is 4.22, 3.94, 3.48 and 2.0 times lower than our NAT yield rate.

It is no surprise that our NAT yield of 1/753 is higher than that from US (1 in 2 million for HIV and HCV),[9] Germany (1 in 431843),[20] Japan (1 in 48262),[21] Singapore (1 in 24567),[17] and Thailand (1 in 25000).[17] The NAT yield reported from various studies in Africa (1 in 14485)[22] and 1 in 24064[23] which is about 19.2 and 32 times lower than us. One of the reasons for this lower NAT yield is that these countries mostly collect blood through voluntary blood donations. The higher NAT yield in India is possibly because of the higher prevalence of these viral infections in our population; 5.7 million[24] with HIV, 12 million with HCV[25] and 40 million with HBV that represent 10% of world HBV-infected population.[26]

In most developed countries, most blood donors are repeat voluntary donors. While in India, voluntary donors constitute only 55% of all blood donors. In our study, there were 35.2% voluntary blood donors which included only 8.4% repeat voluntary blood donors and the remaining 64.8% were replacement donors. The sero prevalence among voluntary blood donors at our blood bank is 0.02%, 0.24% and 0.17% for HIV, HCV and HBV respectively, compared with 0.24%, 1.36% and 0.90%, respectively for replacement donors. The majority of Indian voluntary donors being first-time voluntary donors may not be safer than replacement donors and it could explain the higher NAT yields in India compared to some other Asian countries in spite of an increase in voluntary blood donations.[27]

The benefits of ID-NAT are especially important in patients who receive multiple blood transfusions for diseases such as thalassemia, hemophilia and oncology. Such patients need regular, repeated and life-long blood transfusions and are at higher risk of being infected with serious TTIs. In a survey by the National Thalassemia Welfare Society, among 551 multiple transfused patients with Thalassemia, 33 were HIV-positive, 89 were HCV-positive and 43 were HBV-positive but in our center, out of 199 multi transfused thalassemic patient, 22 (11.1%) were reactive for HCV and 1 (0.5%) patient was reactive for HIV. Transfusion associated common infections in thalassemic patients are Hepatitis C (2.2-44%) followed by HBV (1.2-7.4%) and HIV (0-9%).[28] HCV is the current major problem in Punjab with seroprevalence in blood donors of Northern India ranging from 0.53% to 5.1%,[29] which can be further reduced by screening blood donor samples by ID-NAT.

In the present study, blood donors with a low viral load can sometimes go unrecognized by the discriminatory assays. The discrepancies between multiplex and discriminatory assays observed in the present study should be attributed to the low viremia content of the sample tested rather than to false positive results or to decreased sensitivity of the discriminatory assays. The most likely explanation of discrepant results is stochastic sampling variation in low viral load samples. Regardless of the outcome of the discriminatory probe assay or multiplex repeat assays, it has been recommended to discard all initial NAT reactive donations in order to avoid the infusion of a very low-level viremic unit that was originally detected as reactive by the primary screening assay, but missed in the repeat assays.[30]

In conclusion, our findings showed that the implementation of ID-NAT had a significant affect on the safety of blood supply by allowing rapid detection of three prevalent viruses that cause serious infections. It can also help provide valuable epidemiological data regarding the incidence and prevalence of these viral infections. Within the first 1 year, after implementing ID-NAT, we detected TTIs in 43 samples of donated blood which were missed by serological tests, which helped in preventing the TTIs in 129 patients due to blood components. Universal and routine use of ID-NAT for HIV, HBV and HCV by all blood banks would be an important step in this direction. Current serological tests have made a significant difference, but we are nowhere close to International standards, but it can make our blood supply comparable to the world.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicting Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kurien T, Thyagarajan SP, Jeyaseelan L, Peedicayil A, Rajendran P, Sivaram S, et al. Community prevalence of hepatitis B infection and modes of transmission in Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:670–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaur P, Basu S. Transfusion-transmitted infections: Existing and emerging pathogens. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51:146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia R. Blood transfusion services in developing countries of South-East Asia. Tranfus Today. 2005;65:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodd RY, Notari EP, 4th, Stramer SL. Current prevalence and incidence of infectious disease markers and estimated window-period risk in the American Red Cross blood donor population. Transfusion. 2002;42:975–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch MP, Glynn SA, Stramer SL, Strong DM, Caglioti S, Wright DJ, et al. A new strategy for estimating risks of transfusion-transmitted viral infections based on rates of detection of recently infected donors. Transfusion. 2005;45:254–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch MP, Kleinman SH, Jackson B, Stramer SL, Hewlett I, Preston S. Committee report. Nucleic acid amplification testing of blood donors for transfusion-transmitted infectious diseases: Report of the Interorganizational Task Force on Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing of Blood Donors. Transfusion. 2000;40:143–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40020143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee K, Coshic P, Borgohain M, Premchand, Thapliyal RM, Chakroborty S, et al. Individual donor nucleic acid testing for blood safety against HIV-1 and hepatitis B and C viruses in a tertiary care hospital. Natl Med J India. 2012;25:207–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelfriet CP, Reesink HW, Hernandez JM, Sauleda S, O’Riordan J, Pratt D, et al. Implementation of donors screening for infectious agents transmitted by blood by nuclic acid technology. Vox Sang. 2002;82:87–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00636_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stramer SL, Glynn SA, Kleinman SH, Strong DM, Caglioti S, Wright DJ, et al. Detection of HIV-1 and HCV infections among antibody-negative blood donors by nucleic acid-amplification testing. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:760–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coste J, Reesink HW, Engelfriet CP, Laperche S, Brown S, Busch MP, et al. Implementation of donor screening for infectious agents transmitted by blood by nucleic acid technology: Update to 2003. Vox Sang. 2005;88:289–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00636_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palla P, Vatteroni ML, Vacri L, Maggi F, Baicchi U. HIV-1 NAT minipool during the pre-seroconversion window period: Detection of a repeat blood donor. Vox Sang. 2006;90:59–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weusten J, Vermeulen M, van Drimmelen H, Lelie N. Refinement of a viral transmission risk model for blood donations in seroconversion window phase screened by nucleic acid testing in different pool sizes and repeat test algorithms. Transfusion. 2011;51:203–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giachetti C, Linnen JM, Kolk DP, Dockter J, Gillotte-Taylor K, Park M, et al. Highly sensitive multiplex assay for detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and hepatitis C virus RNA. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2408–19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2408-2419.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allain JP, Candotti D, Soldan K, Sarkodie F, Phelps B, Giachetti C, et al. The risk of hepatitis B virus infection by transfusion in Kumasi, Ghana. Blood. 2003;101:2419–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabarczyk P, van Drimmelen H, Kopacz A, Gdowska J, Liszewski G, Piotrowski D, et al. Head-to-head comparison of two transcription-mediated amplification assay versions for detection of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 in blood donors. Transfusion. 2013;53:2512–24. doi: 10.1111/trf.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg S, Mathur DR, Garg DK. Comparison of seropositivity of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in replacement and voluntary blood donors in western India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44:409–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makroo RN. Impact of routine individual blood donor nucleic acid testing (ID-NAT) for HIV-1, HCV and HBV on blood safety in a tertiary care hospital. Apollo Med. 2007;4:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain R, Aggarwal P, Gupta GN. Need for nucleic Acid testing in countries with high prevalence of transfusion-transmitted infections. ISRN Hematol 2012. 2012:718671. doi: 10.5402/2012/718671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makroo RN, Choudhury N, Jagannathan L, Parihar-Malhotra M, Raina V, Chaudhary RK, et al. Multicenter evaluation of individual donor nucleic acid testing (NAT) for simultaneous detection of human immunodeficiency virus -1 & hepatitis B & C viruses in Indian blood donors. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:140–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hourfar MK, Jork C, Schottstedt V, Weber-Schehl M, Brixner V, Busch MP, et al. Experience of German Red Cross blood donor services with nucleic acid testing: Results of screening more than 30 million blood donations for human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus. Transfusion. 2008;48:1558–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohnuma H, Tanaka T, Yoshikawa A, Murokawa H, Minegishi K, Yamanaka R, et al. The first large-scale nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) of donated blood using multiplex reagent for simultaneous detection of HBV, HCV, and HIV-1 and significance of NAT for HBV. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:667–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heyns AD, Swanevelder JP, Lelie PN, Crookes RL, Busch MP. The impact of individual donation NAT screening on blood safety – The South African experience. ISBT Sci Ser. 2006;1:203–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cable R, Lelie N, Bird A. Reduction of the risk of transfusion-transmitted viral infection by nucleic acid amplification testing in the Western Cape of South Africa: A 5-year review. Vox Sang. 2013;104:93–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2012.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNAIDS, 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. HIV and AIDS estimates and data 2005 and 2003. [Last accessed on 2013 Sept, 11]. Available from: http://www.data.unaids.org/pub/globalReport/2006/2006_GR)ANN2_en.pdf .

- 25.Kumari S. WHO Report on Overview of hepatitis C problem in countries of South-East Asia Region. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 11]. Available from: http://www.sero.who.Int/EN/Section10/Section17/Section58/Section220_217.htm .

- 26.Khan M, Dong JJ, Acharya SK, Dhagwahdorj Y, Aabbas Z, Jafri W, et al. Hepatology issues in Asia; Perspectives from regional leaders. J Grasteroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(Suppl 7):419–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allain JP. Volunteer Safer than replacement blood donor: A myth revealed by evidence. ISBT Sci Ser. 2010;5:169–75. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain R, Perkins J, Johnson ST, Desai P, Khatri A, Chudgar U, et al. A prospective study for prevalence and/or development of transfusion-transmitted infections in multiply transfused thalassemia major patients. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2012;6:151–4. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.98919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain A, Rana SS, Chakravarty P, Gupta RK, Murthy NS, Nath MC, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibodies among the voluntary blood donors of New Delhi, India. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:695–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1024887211146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAuley JD, Caglioti S, Williams RC, Robertson GF, Morgan L, Tobler LH, et al. Clinical significance of nondiscriminated reactive results with the Chiron Procleix HIV-1 and HCV assay. Transfusion. 2004;44:91–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]