Abstract

Attenuation of the p53 protein is one of the most common abnormalities in human tumors. Another important marker of tumorigenesis is focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a 125-kDa tyrosine kinase that is overexpressed at the mRNA and protein levels in a variety of human tumors. FAK is a critical regulator of adhesion, motility, metastasis, and survival signaling. We have characterized the FAK promoter and demonstrated that p53 can inhibit the FAK promoter activity in vitro. In the present study, we showed that p53 can bind the FAK promoter-chromatin region in vivo by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. Furthermore, we demonstrated down-regulation of FAK mRNA and protein levels by adenoviral overexpression of p53. We introduced plasmids with different mutations in the DNA-binding domain of p53 (R175H, p53 R248W and R273H) into HCTp53−/− cells and showed that these mutations of p53 did not bind FAK promoter and did not inhibit FAK promoter activity, unlike wild type p53. We analyzed primary breast and colon cancers for p53 mutations and FAK expression, and showed that FAK expression was increased in tumors containing mutations of p53 compared to tumors with wild type p53. In addition, tumor-derived missense mutations in the DNA-binding domain (R282, R249, and V173) also led to increased FAK promoter activity. Thus, the present data show that p53 can regulate FAK expression during tumorigenesis.

Keywords: p53, focal adhesion kinase, breast cancer, colon cancer, tumor

Introduction

It is known that the p53 tumor suppressor is the most frequent target for genetic alterations in human cancers and is mutated in almost 50% of all tumors [1–5]. Following induction by a variety of cell stresses such as DNA damage, hypoxia, and oncogene activation, p53 up-regulates a set of genes that can promote cell death and growth arrest, such as p21, GADD45, cyclin G, and Bax (reviewed in [6]). Recently, it was shown that p53 can repress promoter activities of a number of antiapoptotic genes and cell-cycle genes [survivin, cyclin B1, cdc2, cdc25 c, stathmin, Map4, bcl-2, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK)] [7]. In the present study, we have explored the potential link between p53 and FAK expression.

FAK is a 125-kDa nonreceptor tyrosine kinase localized at the focal adhesions [8], which are the contact points between cells and their substratum, and are the sites of intense tyrosine phosphorylation [9]. FAK is tyrosine phosphorylated in response to a number of stimuli, including clustering of integrins, plating on fibronectin, and in response to a number of mitogenic agents [10]. It has been shown that FAK is overexpressed in a number of tumors: breast, colon, melanomas, thyroid, sarcomas, cervical carcinomas, and other tumors [11]. Recently, FAK has been shown to play role in survival, angiogenesis, and metastasis signaling, and has been proposed as a new potential therapeutic target in cancer [12,13].

We have shown increased FAK mRNA and protein levels in primary tumors [14], and subsequently cloned the human FAK promoter and found that it contains p53 binding sites [7]. In the present study, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays and showed that p53 can bind the FAK promoter-chromatin region in vivo. In addition induced endogenous p53 increased binding to FAK promoter and blocked FAK mRNA and protein expression. We showed that adenoviral expression of p53 in HCT116 p53−/− colon cancer cells reduced the FAK mRNA and protein levels. Dual-luciferase assay with the FAK promoter construct detected that mutant p53 in the DNA-binding domain (R175H, R248W, and R273H) did not bind to the FAK promoter and did not inhibit FAK promoter activity. In addition, we screened for p53 mutations in breast and colon tumors and found that p53 mutations correlated with FAK overexpression in these tumors. Moreover, tumor-derived p53 mutations had abrogated FAK had abrogated FAK promoter activity. Thus, the linkage of p53 and FAK is important for development of targeted therapy of tumors with mutant p53 and FAK overexpression.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Cell Culture

HCT116 p53 −/− colon cancer cells were kindly provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and maintained in McCoy's 5A medium 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 μg/mL insulin, and 2 mM l-glutamine. BT474 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 μg/mL insulin, and 2 mM l-glutamine. MEFp53−/− and p53+/+ cells were maintained in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 250 ng/mL amphotecin B.

Antibodies, Plasmids, and Reagents

For immunological analyses, the antibodies used were anti-FAK 4.47 (Upstate Biologicals, Charlottesville, VA), and anti-p53 monoclonal antibody Ab-6, clone DO-1 (Oncogene Research, Inc., San Diego, CA), antivinculin antibody was from Sigma, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). For the ChIP analysis, control C-myc tagged antibody was obtained from (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Anti-β-Actin was obtained from (Sigma, Inc.). Wild type p53 and R273, R248W, and R175H-p53 constructs were kindly provided by Dr. Daiqing Liao (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL). Wild type p53 and R282W, R249, V173M p53 mutant plasmids, described in [15] were kindly provided by Dr. Rainer K. Brachmann (University of California, Irvine, CA). All p53 mutations were confirmed by sequencing. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) was obtained from (Sigma, Inc.).

Tumor Samples

Tumor (breast and colon) and matched control tissue samples were obtained from the UF Molecular Tissue Bank with IRB approval (Department of Pathology, University of Florida). DNA and RNA were isolated using the DNAzol reagent (Promega, Inc., Madison, WA). Slides from tissue and normal samples were prepared, as described in [14], at the Immunohistochemistry Core facility (Department of Pathology, University of Florida).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP assay was performed with the Upstate, Inc. ChIP kit, according to the manifacture's protocol. Primers for the FAK promoter were: forward primer #1 from −1020 to −1000 of FAK promoter (Accession number AY323812; [7]): 5′-TCACTTCCTGCTTAAAGCCC-3′, forward primer #2 from −920 to −900 of the FAK promoter (Accession number of sequence AY323812 [7]): 5′-CTCCAACCTCGCCTTTTGC-3′ and reverse primer: 5′- GGGACTTAGAAGTC CACTGG-3′. The third set of primers #3 for PCR was from −106 to +47 of the FAK promoter: forward: 5′GCTGCCGAGAGAGGACGCG-3′ and reverse: 5′-TTCCT CCCACGCCTCACG-3′. Primers for 3′untranslated region (3′-UTR) of FAK gene were from 3391 to 3741 bp of sequence Accession number L13616: forward primer 5′-TTTTGAAGATGTTCTC-TAGC-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-TTAAGATGTCAC-CC CTTGGC-3′. PCR was performed, as previously described [7]. Primers for p21 promoter were: forward primer: 5′-ACAGCAGAG GAGAAAGAAGCC-3′ and reverse: 5′-ATTACTGACATCTC AGGCTGC-3′. Primers for GAPDH promoter were: forward primer: 5′-TTGAACCAGGCGGCTGCGGA-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-GGAGGCTGCG GGCTCAATTT-3′.

Adenoviral Transduction

Adenoviruses containing the p53 gene and GFP gene were obtained from Dr. J. Samulski and the Gene Therapy Center Virus Vector Core Facility of the University of North Carolina and described in [16]. Cells were infected with Ad-p53 or Ad-GFP at an optimal concentration of virus (500 ffu, focus forming units/cell) for each cell line, as determined in [17]. Optimal concentrations of virus caused protein expression in 100% of the cells without visible toxic effect.

5-Fluorouracil Treatment

Cells were treated with 5-FU at 0.5 mM for 24 h, as described [18]. The FAK protein level in lysates was analyzed by Western blotting and mRNA level by real-time PCR.

RNA Isolation

Total cellular RNA was isolated from cultured cells with a NucleoSpin RNA II Purification Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Real-Time PCR

For FAK cDNA amplification by RT-PCR, TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix was used (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RT-PCR Primers and TaqMan probes and PCR conditions were described previously in [14]. For normalization purposes, we used RT-PCR with primers for GAPDH, forward: 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′, and reverse 5′-GA-AGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′ and probe 5′-FAM-CAAGCTTCCC GTTCTCAGCCT-3′-TAMRA. The ABI PRISM 7700 cycler's software calculated a threshold cycle number (Ct) at which each PCR amplification reached a significant threshold level.

Dual-Luciferase Assay

Dual-luciferase assay was performed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System kit (Promega, Inc.). For normalization of luciferase activity, the pRL-TK control vector, encoding Renilla luciferase was used, as described in [7]. Luminescence was measured on a Luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA).

Single Stand Conformational Polymorphism (SSCP) Analysis

SSCP mutation analysis for p53 exons 4–8 was performed, as described in [19]. PCR products were denatured and analyzed on native polyacrylamide gels, as described in [19]. Silver staining patterns of the single-stranded products were examined for aberrant bands. And the samples with abnormal single strand patterns were sequenced for detection of mutation and compared with matched normal sample.

Loss of p53 Heterozygosity (LOH) Analysis

Loss of heterozygocity (LOH) analysis at exon 4 (codons 68 and 72) and intron 6 were performed by PCR amplification of the fragment and then by restriction digestion. Exon 4 polymorphisms at codons 68 and 72 were screened with the enzymes Alw NI and Bst UI, respectively, while intron six polymorphisms were screened with Msp I. Unaffected (normal) DNA from patients was genotyped at specific loci, digested and subjected to polyacrylamide electrophoresis (PAGE) to determine p53 heterozygosity by the presence of three bands on PAGE for heterozygous samples in the patient's germline. For patients positive for p53 heterozygosity, their affected (tumor) DNA was genotyped at that locus to check for allelic loss (detected by differences in band intensities or complete absence of an allele).

DNA Sequence Analysis

Positive samples (PCR products with abnormal SSCP patterns) were purified with Millipore Microcon-PCR Centrifugation devices and sequenced using Big Dye Terminator 2 chemistry (ABI) and ABI 310 genetic analyzer or tBI 377 sequencer. Data were analyzed using SeqEd v.1.0.3 (ABI) software and Sequencher v.4.5 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) software.

Western Blotting

Immunofluorescent staining, Western blot analysis, and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously [16].

Immunohistochemistry Staining

FAK staining was performed on normal and matched tumor slides, as described previously with FAK 4.47 antibodies [11]. A single-board-certified pathologist (Dr. Nicole Massoll) scored each slide for FAK expression based on a scoring system that measured intensity (0, none; 1, borderline; 2, weak; 3, moderate; 4, strong), and percentage of positive cells (0–100%). FAK expression was considered as high with 3+ or 4+ intensity and >90% positive cells.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

p53 Binds to the FAK Promoter In Vivo

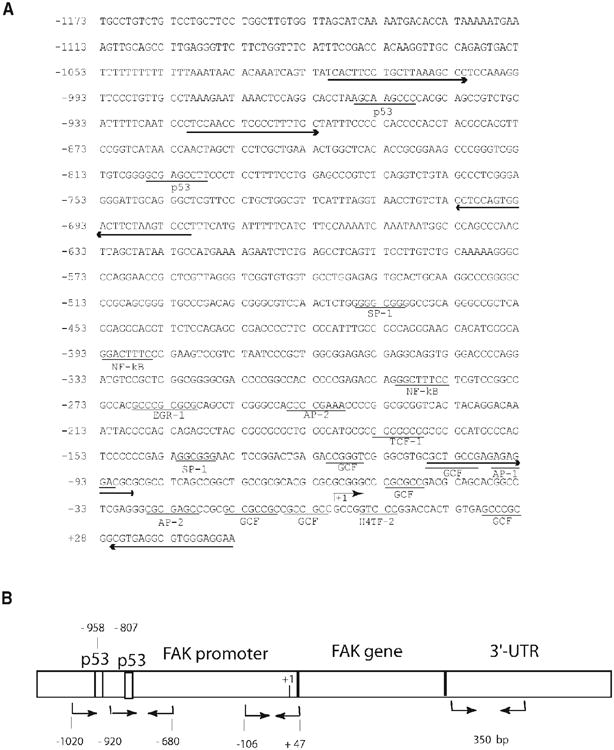

Although wild type p53 can bind the FAK promoter in vitro [7], it has not been shown to bind in vivo at the chromatin level in cancer cells. To demonstrate this binding, we performed ChIP assays with p53 antibody, and performed PCR with the two sets of FAK promoter primers from −1020 and −920 to −680 bases shown in Figure 1A and B in p53 positive, HCTp53+/+ and p53-negative, p53−/− cells (Figure 1C, upper panel). P53 bound the FAK promoter in HCTp53+/+ cells, but not in HCTp53−/− cells (Figure 1, upper panel). Both primer sets covering p53 sites demonstrated binding with the FAK promoter. In addition, PCR was negative in samples precipitated without antibody or with control C-myc tagged antibody (Figure 1C). The same p53 binding results were obtained in a ChIP assay with a known positive control p53 target, p21 (Figure 1C, middle panel). No binding was present with a negative control, GAPDH promoter (Figure 1C). No binding of p53 was observed by PCR with primers from −106 to +47 covering FAK promoter region without p53 binding sites (not shown) and with a negative control primers from the 3′-UTR region of FAK gene (Figure 1C, lower panel). Thus, the p53 transcription factor is able to bind the FAK promoter on a chromatin level in vivo.

Figure 1.

(A,B) The scheme of FAK promoter with p53 binding sites and primers used for ChIP assay. (A) FAK promoter sequence is shown with p53 sites underlined, and primers used for ChIP assay are shown by arrows in forward and reverse directions. FAK promoter sequence (Gene Bank Accession number AY323812 [7]) has two p53 binding sites, two NF-kappa B binding sites, SP-1, GCF, TCF-1, H4TF-2, AP-2, and other binding sites. Transcription initiation site (G) is marked as +1 [7]. Numbers to the left show bases upstream (−) and downstream (+) from the start of transcription. (B) The scheme of primers used for ChIP assay. The lengths of FAK fragments are shown not in scale on the scheme. Two primer sets: forward primer starting from −1020 and another forward primer starting from −920 with the reverse primer starting from −680 that covered p53 binding sites were used for PCR in ChIP assay. Another set of primers for PCR in the FAK promoter were from −106 to +47 in the region without p53 binding sites. The negative control primers were from three-untranslated 3′UTR region of FAK gene, positions from 3393 to 3721 of FAK cDNA sequence (Accession number L13616) are shown on the right. (C) p53 binds FAK promoter in vivo by ChIP assay. Immunoprecipitation with p53 monoclonal antibody was performed on HCT116 p53−/− and HCT116 p53+/+ colon cancer cells that were cross-linked, as described in Upstate ChIP protocol. PCR was performed with immunoprecipitated DNA using FAK promoter primers from −920 to −680 bases of FAK promoter sequence shown on Figure 1B (upper panel), p21 promoter primers (middle panel), and GAPDH promoter and FAK 3′-UTR (untranslated) region primers (lower panels) (Materials and Methods Section). Left lane has Molecular Weight Marker. Input and genomic DNA were used as a positive control. No antibody and control antibody (c-Myc tag) were used as a negative controls. The ChIP assay shows binding of p53 to the FAK promoter in vivo in HCT116p53+/+ cells, and absence of binding in HCT116 p53−/− cells. The ChIP assay with the positive control had the same results with p21 control primers, resulted in the binding of p53 to the p21 promoter in p53+/+ cells (middle panel). ChIP assay with negative control GAPDH promoter and FAK 3′-UTR primers resulted in the negative binding in both p53+/+ and p53−/− cell lines (lower panels).

p53 Inhibits FAK mRNA and Protein Level in Cancer Cells

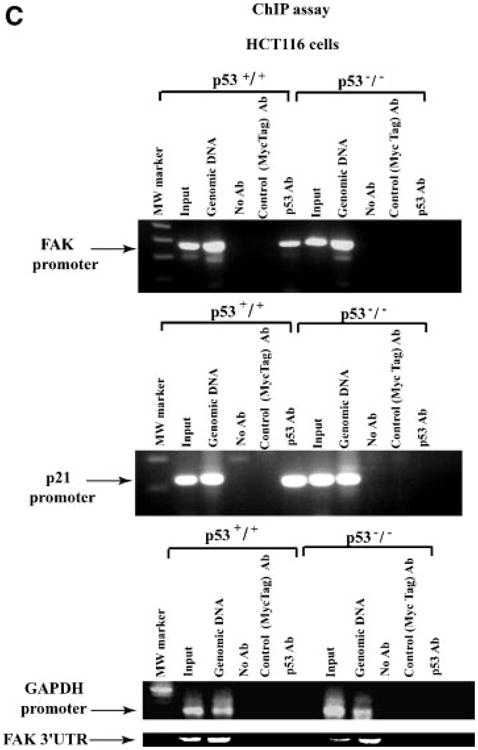

Since we have shown that p53 can bind to the FAK promoter in vitro [7] and in vivo and decrease its luciferase activity [7], we induced expression of endogenous p53 and tested its effect on FAK expression in p53-null and p53+/+ cells. It has been demonstrated recently that 5-FU increased binding of p53 to the numerous regulatory regions of genes and regulated their expression in a p53-dependent manner [20], but the effect of p53 overexpression on FAK mRNA and protein levels has never been described. Thus, we tested the effect of endogenous p53 on the expression of FAK in normal MEF fibroblasts p53+/+ and control MEF p53−/− cells (Figure 2A). Treatment with 5-FU induced p53 and decreased the level of FAK expression in MEF 53+/+ cells compared with MEF p53−/− cells (Figure 2A). The same result was observed in HCT116 p53−/− and HCTp53+/+ colon cancer cells, where treatment with 5-FU induced p53 level and significantly decreased the level of FAK protein in HCT116 p53+/+ cells. Similarly, induction of p53 by 5-FU in MEFp53+/+ cells led a significant reduction of FAK mRNA compared to MEFp53−/− cells (Figure 2B). Similarly, treatment of HCT116 colon cancer cells with 5-FU significantly blocked FAK mRNA in HCT116 p53+/+ cells compared with HCT116p53−/− cells (Figure 2C). These results show that induced endogenous p53 causes decrease in levels of FAK protein and mRNA expression.

Figure 2.

(A,B) Increased p53 inhibits FAK protein and mRNA expression in 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-treated MEF p53−/− and MEFp53+/+ cells. (A) Normal MEFp53−/− and MEFp53+/+ cells were treated with 0.5 mM 5-FU for 24 h. Untreated and treated cells were analyzed for FAK expression by Western blotting with anti-FAK antibodies. Treatment with 5-FU increased p53 in MEFp53+/+ cells and inhibited FAK protein expression compared to MEF−/− cells. Equal protein loading was controlled by Western blotting with beta-Actin antibody. (B) Untreated and 5-FU treated MEFp53−/− and MEF+/+ cells were collected and RNA was isolated. Real-time PCR was performed with FAK and GAPDH primers using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit protocol (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR data obtained with FAK primers were normalized to the level of RNA obtained with GAPDH and expressed relatively to GAPDH control. Real-time PCR demonstrates significantly decreased FAK mRNA in 5-FU-treated MEFp53+/+ cells compared to MEFp53−/− cells. P<0.05 MEFp53+/+ versus control MEFp53−/− cells. (C) Increased p53 inhibits mRNA expression in 5-FU-treated colon cancer HCT116 p53−/− and HCT116 p53+/+ cells. The same analysis as shown on Figure 2B was performed on HCTp53−/− and HCT116 p53+/+ cells. FAK mRNA was significantly decreased in HCT116 p53+/+ cells treated with 5-FU compared with HCT116 p53−/− without and with 5-FU-treatment. Real-time PCR data obtained with FAK primers were normalized to the level of RNA obtained with GAPDH and expressed relatively to GAPDH control. P<0.05 HCT116 p53+/+ with 5-FU treatment versus control HCT p53−/− cells. (D) Induced p53 increases binding to the FAK promoter. HCTp53−/− and HCT116 p53+/+ cells were treated with 0.5 mM 5-FU for 24 h, and used for ChIP assay (Materials and Methods Section) Immunoprecipitation of p53 with monoclonal p53 antibody was performed on HCT116 p53−/− and HCT116 p53+/+ colon cancer cells without and with fluorouracil treatment, as described in Materials and Methods Section. PCR was performed with immunoprecipitated DNA using FAK promoter primers from −920 to −680 bases of the FAK promoter sequence, as shown in Figure 1C. Induced p53 increases binding to the FAK promoter in p53+/+ cells but not in p53−/− cells. Upper panel: ChIP with p53 antibody, lower panel: inputs.

Finally, we analyzed binding of induced endogenous p53 to the FAK promoter by ChIP assay on HCT116 p53+/+ and control HCTp53−/− cells without and with 5-FU treatment (Figure 2D). We clearly showed that 5-FU treatment increased binding of induced p53 to the FAK promoter in p53+/+ cells, but not in p53−/− cells (Figure 2D). Taken together, these results show that p53 binds to the FAK promoter in vivo, and inhibits the expression of FAK mRNA and protein.

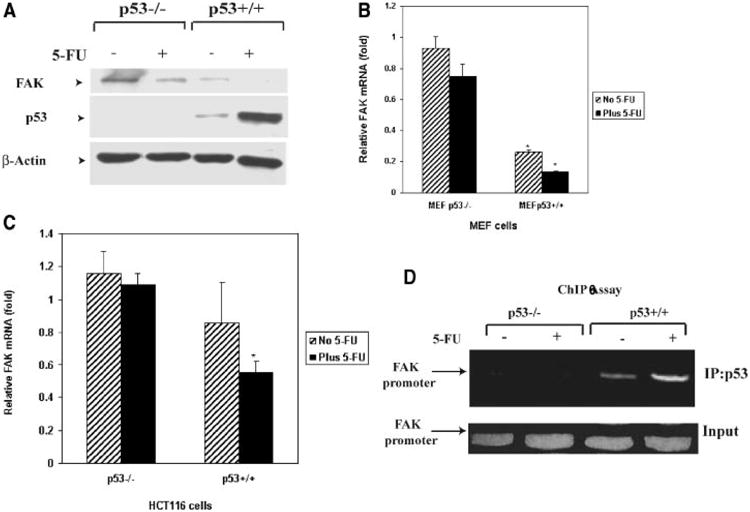

Next, we tested the effect of p53 on FAK expression by introducing adenoviral p53 and control GFP into p53 negative HCT116 p53−/− cells (Figure 3A). We observed a decreased level of FAK protein expression after 24 h of infection with Ad-p53, but not with Ad-GFP (Figure 3A), demonstrating a direct p53 inhibitory effect on the FAK protein level. To determine the effect of p53 expression on FAK mRNA levels, we next performed real-time PCR analyses on HCT p53−/− cells treated with Ad-GFP and Ad-p53 under the same conditions (Figure 3B). p53 significantly decreased the FAK mRNA levels in HCTp53−/− cells, while control Ad-GFP did not have this inhibitory effect (Figure 3B). Thus, expression of p53 in p53−/− cells inhibited FAKmRNA and protein levels.

Figure 3.

(A) Adenoviral p53 blocks FAK expression in HCT116 p53−/− cells. HCT116 p53−/− cancer cells were infected with Ad-GFP and Ad-p53 adenoviruses for 24 h. Western blotting was performed with FAK, p53, and GFP antibodies (Materials and Methods Section) to test the expression of FAK, p53, and GFP, respectively. Adenoviral p53 blocked FAK protein expression in cancer cells. To control for equal protein loading, Western blotting was performed with β-Actin antibody. (B) Real-time PCR analysis demonstrates decreased FAK mRNA after p53 expression in HCT116 p53−/− cells. HCT116 p53−/− cells were treated with adenoviruses, containing p53 and control GFP genes, Ad-p53 and Ad-GFP, for 24 h, and total RNA was isolated from untreated and treated cells. Real-time PCR was performed with FAK and GAPDH primers using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit protocol (Applied Biosystems). The relative mRNA level is shown normalized to untreated samples ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. FAKmRNA was significantly decreased by p53 (*P < 0.05, Ad-p53-treated samples versus control GFP-treated samples).

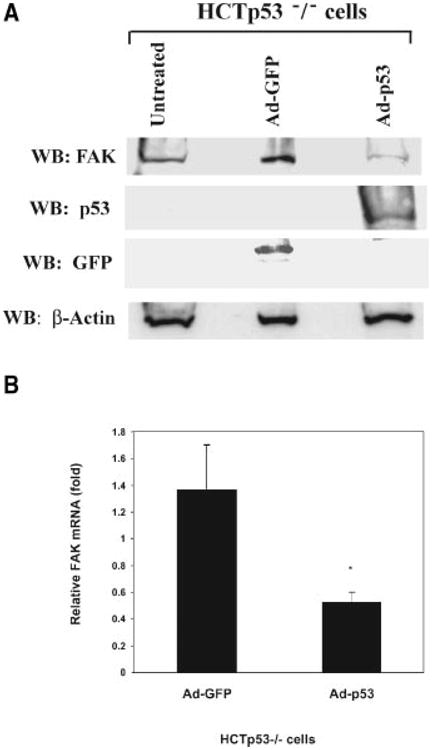

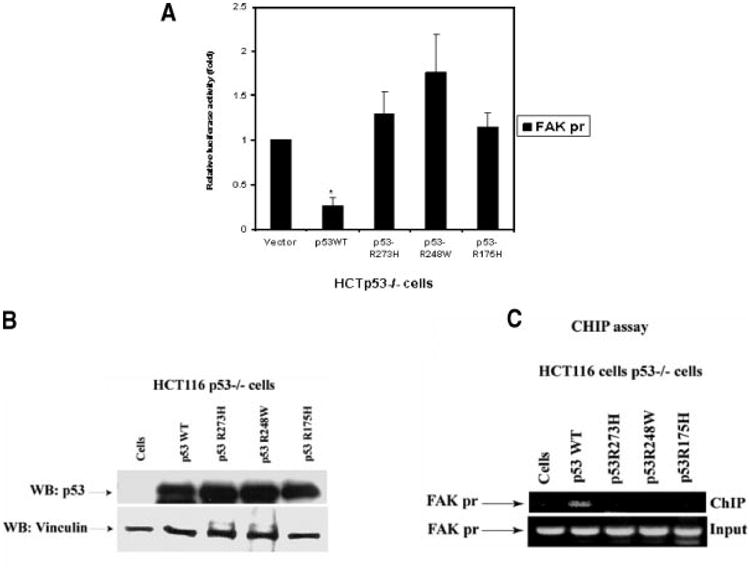

Mutants of p53 in the DNA-Binding Domain Did Not Cause an Inhibitory Effect on FAK Promoter Activity in Contrast to Wild Type p53

Since we have shown that wild type p53 inhibited FAK promoter activity [7], we tested p53 mutations to their effects on FAK promoter activity. To test the effect of different mutations in the central DNA-binding domain of p53 on FAK promoter, we used missense mutations: R175H, R248W, and R273H (known as “hot-spot” tumor mutations) [21] to compare their effects with wild type p53. We cotransfected p53 wild type and mutant plasmids with the P-1020 FAK-promoter construct into p53-null HCT116 p53−/− cells, and performed dual-luciferase assays (Figure 4A). Mutants of p53 did not inhibit FAK promoter luciferase activity, but wild type p53 did (Figure 4A). In fact, the FAK promoter activity was significantly higher in cells transfected with mutant p53 than cells transfected with wild type p53 (Figure 4A). The same effect was observed with a control p21-promoter construct, whereby p53 mutants did not activate the promoter, but wild type p53 did (not shown). All p53 plasmids resulted in equal expression of protein in HCT116 p53−/− cells transfected with wild type and mutant p53, as demonstrated by Western blotting with p53 antibody (Figure 4B). In addition, we performed a ChIP assay and showed that wild type p53 binds FAK promoter in vivo, but mutants of p53 (R175H, R248W, and R273H) do not bind to the FAK promoter (Figure 4C). Thus, mutations in the DNA-binding domain of p53 did not bind the FAK promoter and did not have an inhibitory effect on FAK-promoter activity.

Figure 4.

(A) Mutations of p53 DNA binding domain (R273H, R248W, and R175H) don't inhibit FAK-promoter activity in contrast to the wild type p53. We co-transfected p53 mutants (R273H, R248W, and R175H) and p53 wild type with FAK P-1020-pGL3 luciferase vector into p53-null HCT116 cells. After 24 h, cell lysates were analyzed in a dual-luciferase assay (Materials and Methods Section). Wild type p53 inhibited FAK promoter activity, while mutants did not repress its activity. The dual-luciferase activity was normalized relatively to the vector control sample. *P<0.05, FAK promoter activity in cells transfected with wild type p53 plasmids versus control cells transfected with vector alone or with mutant p53 plasmids. (B) Expression of p53 proteins in HCT116 p53−/− cells. Cell lysates transfected with wild type p53 and mutant p53 (R273H, R248W, and R175H) constructs were analyzed by Western blotting with p53 antibody (clone DO-1). Equal protein loading was analyzed with antivinculin antibody. All p53 proteins expressed at equal levels in HCT p53−/− cells. (C) Mutations of p53 DNA binding domain (R273, R248, and R175) don't bind FAK promoter in contrast to wild type p53. We transfected p53 mutants (R273H, R248W, and R175H) and p53 wild type plasmid into HCT116 p53−/− cells and performed ChIP assay, as described in Figure 1C. Immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by PCR with the FAK-promoter primers (from −920 to −680, Figure 1B), as described (Materials and Methods Section). Wild type p53 binds FAK promoter, while p53 mutants don't. Upper panel: ChIP samples, lower panels: inputs.

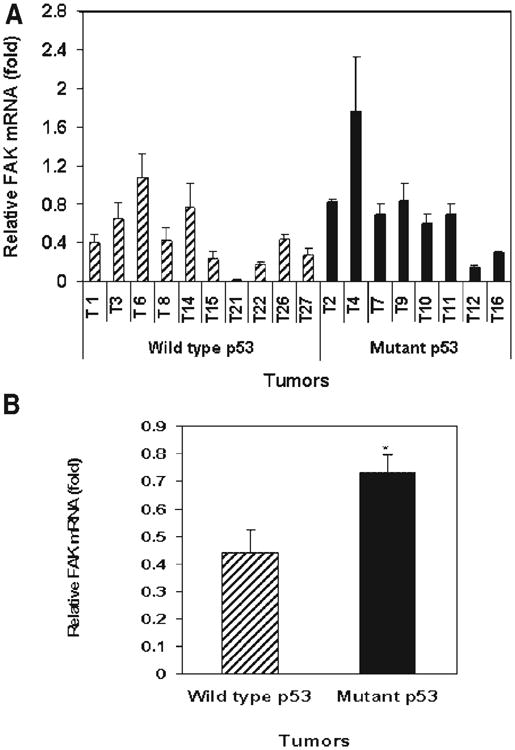

Tumors With p53 Mutations Overexpress FAK

Since wild type p53 inhibited FAK mRNA and protein expression, while mutations of p53 in the DNA binding domain did not inhibit FAK promoter activity, we compared expression of FAK mRNA and protein levels with the p53 status of primary human tumors. We analyzed 18 primary breast and colon tumors for p53 abnormalities using SSCP (single-strand conformation polymorphism) analysis of exons 4–8 and LOH (loss of heterozygosity) analysis at three loci (codons 68 and 72 in exon 4, and intron 6), detecting p53 mutations in 8 (44%) of 18 tumors (Table 1).

Table 1. Spectrum of p53 Mutations and LOH in Breast and Colon Tumors.

| Mutation and LOH | FAK expressiona | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Tumor number | Type | Nucleotide(s) change | Codon | Amino acid change | Exon | Intensity | % Positive | Level of expressiona |

| 2 | Breast | AGG→GGG | 249 | Arg→Gly | 7 | 4 | 100 | High |

| 4 | Colon | GTG→ATG | 173 | Val→Met | 5 | 3 | 100 | High |

| 7 | Colon | LOH | 72 | 4 | 3 | 95 | High | |

| 9 | Breast | G-insert | 67 | 4 | 2 | 95 | Low | |

| LOH | Intron 6 | |||||||

| LOH | 68, 72 | 4 | ||||||

| 10 | Colon | LOH | Intron 6 | 3 | 100 | High | ||

| 11 | Colon | CGG→TGG | 282 | Arg→Trp | 8 | 3 | 95 | High |

| 12 | Colon | CCT deletion | 191 | Pro deletion | 6 | 3 | 20 | Low |

| LOH | Intron 6 | |||||||

| 16 | Breast | CGG→GGG | 282 | Arg→Gly | 8 | 2 | 100 | Low |

FAK expression were considered high with intensity equal to 3 or 4 and detected >90% of cells. SSCP, LOH, and sequencing analyses were performed on 18 breast and colon tumors.

We performed real-time PCR analysis of these 18 tumors (Figure 5A) and demonstrated significantly increased FAK mRNA in tumors with the mutant p53 compared with tumors containing wild type p53 (Figure 5B). Immunohistochemical analyses on these tumors demonstrated high FAK protein expression in 8 (44%) of the 18 tumor samples. FAK was expressed at high levels in 63% of tumors with p53 mutations in contrast to only 30% of tumors with wild type p53.

Figure 5.

(A,B) Real-time PCR analysis demonstrates increased FAK mRNA in tumors with p53 mutations versus tumors with wild type p53. Real-time PCR was performed with FAK and GAPDH primers on 18 tumors using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit protocol (Applied Biosystems). The relative mRNA level normalized to the GAPDH control is shown ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. (A) FAK mRNA levels are shown in individual tumor samples with wild type p53 and tumors with mutant p53. (B) FAK mRNA in the pooled samples of tumors with wild type p53 and in the tumors with mutant p53. FAK mRNA level was higher in tumors with mutant p53 versus tumors with wild type p53. *P<0.05, mRNA in tumors with mutant p53 versus tumors with wild type p53, Student's t-test.

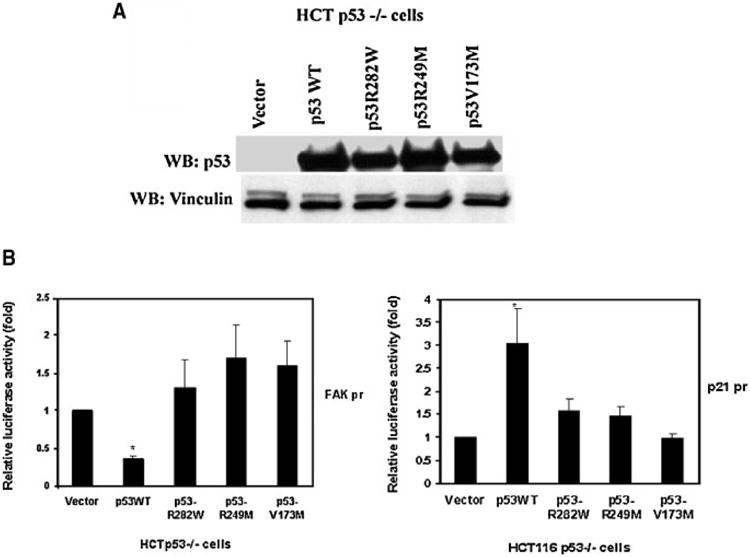

Tumor-Derived p53 Mutations Do Not Inhibit FAK Promoter Activity

In our tumors with p53 mutations, there were three different mutations in the DNA-binding domain (R249, V173, and R282). We obtained these constructs of p53 and tested their effect on FAK promoter activity in HCTp53−/− cells. All p53 proteins expressed at equal levels in HCT116 p53−/− cells transfected with wild type and mutant p53 plasmids (Figure 6A). We clearly showed that while wild type p53 inhibited FAK promoter activity, the p53 mutants did not (Figure 6B, left). A similar result was obtained with a control p21 promoter (Figure 6B, right). Thus, the tumor-derived p53 mutations did not inhibit FAK promoter, strongly supporting the regulation of FAK expression by p53. Thus, we observed increased expression of FAK mRNA and protein in tumors with mutant p53 consistent with our data in cancer cell lines.

Figure 6.

(A,B) Tumor-derived p53 mutants (R249, V173, and R282) have defect in FAK promoter activity. We cotransfected wtp53 and missense p53 mutations (R249M, V173M, R282W), derived from tumors in codons that resulted in high FAK expression. (A) All protein expressed at equal levels, as demonstrated by Western blotting with p53 antibody (clone DO-1) (Materials and Methods Section). Vinculin antibody was used a control for equal protein loading. (B) For cotransfection we used wild type p53 (WTp53) and mutant p53 with FAK promoter luciferase construct (left panel) and p21 (right panel) as a positive control promoter construct into HCTp53−/− cells. Dual-luciferase assay demonstrates that wild type p53 inhibited FAK promoter luciferase activity, but tumor-derived p53 mutations did not. The same result was obtained on control p21 promoter, wild type p53 induced p21 -promoter activity, but mutants did not. P<0.05, FAK promoter activity in cells transfected with wild type p53 plasmids versus control cells transfected with vector alone or with mutant p53 plasmids.

Discussion

In the present report, we demonstrated that normal p53 binds to the FAK chromatin-promoter region in vivo. Moreover, we showed that induced endogenous p53 and exogenous overexpression of wild type p53 inhibited FAK mRNA and protein levels in the p53-null HCT116 colon cancer cell line. This demonstrates direct regulation of FAK expression by p53. Conversely, we showed that mutations of p53 in its DNA-binding domain did not lead to inhibition of FAK promoter luciferase activity, as wild type p53 did. We demonstrated increased FAK mRNA and protein expression in primary tumors with p53 mutations of breast and colon tumor samples. Moreover, tumor-derived mutants (R249, V173, and R282) that resulted in high FAK expression caused no inhibition of the FAK promoter, in contrast to wild type p53. Taken together, these results show a novel role for p53 in human tumorigenesis.

Recently, global characterization of 65 572 p53 ChIP DNA fragments was done on 5-FU-treated HCT116 colorectal cancer cells to determine potential targets of activated p53 [20]. The authors identified a number of novel targets, including PTK2 (FAK) that was involved in cell adhesion, migration, and metastasis [20], consistent with our ChIP assays. These 5-fluouracil-treated HCT116 cells inhibited FAK [20], leading the authors to suggest that p53 can suppress metastasis through repression of FAK.

However, as we have shown, once p53 is mutated, FAK is up-regulated and overexpressed, promoting tumor invasion and metastasis. These data are consistent with the oncogenic properties of p53 mutants [22], whereby mutant p53 can exhibit a dominant negative effect through inactivation of the function of wild type p53. In fact, our previous results have demonstrated that high FAK expression is associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype [11]. Thus, we have demonstrated a direct link of p53 mutation to FAK overexpression.

In addition we observed that treatment of tumor cells with 5-FU downregulated FAK and increased p53 expression. Furthermore, 5-FU caused an increase in binding of p53 to the FAK promoter. This result is consistent with our previous data on melanoma cells that down-regulated FAK in response to 5-FU [18]. Down-regulation of FAK with antisense oligonucleotides combined with 5-FU chemotherapy resulted in greater loss of adhesion and apoptosis in melanoma cells than treatment with either agent alone, suggesting that the combination may be a potential therapeutic agent for melanoma in vivo [18]. In this study, we extended these findings whereby 5-FU increased endogenous p53 in cancer cells that down-regulated FAK, suggesting a potential for future therapeutics.

In a similar way, we observed that missense mutations, frequently seen in breast and colon tumors in the p53 DNA-binding domain [21], did not cause inhibition of FAK promoter activity. In fact, FAK promoter activity was higher in cells expressing mutant p53 than in cells expressing wild type p53. In addition, FAKmRNA level was significantly higher in tumors with mutant p53 compared with tumors containing wild type p53. In approximately 50% of human tumors, p53 is inactivated as a result of missense mutation in the DNA-binding domain [21]. There are two types of mutants, conformational mutants that change the structure of protein, such as R249, R175, and V143; and the DNA contact site mutants, such as R248 and R273, that have mutation at a site of wild type p53 that is directly involved in binding DNA [22]. In our studies, six different p53 mutations with known defects in DNA-binding did not cause result in inhibition of FAK promoter activity, while wild type p53 inhibited FAK promoter activity.

In conclusion, this is the first study demonstrating that p53 directly regulates FAK expression and that p53 mutations resulted in high FAK promoter activity and high FAK expression in human cancer cells. This is the first step for analysis of p53-mediated FAK expression and signaling during tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Molecular Tissue Bank (Department of Pathology, UF) for providing slides and DNA for SSCP and sequencing analyses. We would like to thank Dr. Li Zhang (Molecular Core Facility, UF) for technical help in real-time-PCR analysis. We would like to thank Drs. Daiqing Liao (UF Shands Cancer Center, University of Florida, FL) and Dr. Rainer K. Brachmann (University of California Medial Center) for a kind gift of p53 mutant and wild type plasmids. We would like to than Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD) for kind gift of HCT116 p53−/− and HCTp53+/+ cell lines. We would like to thank Christopher Virnig and Min Zheng for excellent technical help. Supported by a Hayward Foundation grant (M.R. Wallace), Susan G. Komen for the Cure grant (V. M. Golubovskaya) and NIH grant CA65910 (W. G. Cance).

Abbreviations

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- SSCP

single stand conformational polymorphism

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

References

- 1.Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, et al. p53 gene mutations occur in combination with 17p allelic deletions as late events in colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7717–7722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidransky D, Mikkelsen T, Schwechheimer K, Rosenblum ML, Cavanee W, Vogelstein B. Clonal expansion of p53 mutant cells is associated with brain tumour progression. Nature. 1992;355:846–847. doi: 10.1038/355846a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollstein M, Hergenhahn M, Yang Q, Bartsch H, Wang ZQ, Hainaut P. New approaches to understanding p53 gene tumor mutation spectra. Mutat Res. 1999;431:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willis AC, Chen X. The promise and obstacle of p53 as a cancer therapeutic agent. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:329–345. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Rastinejad F, El-Deiry WS. Restoring p53-dependent tumor suppression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:S55–S63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giaccia AJ, Kastan MB. The complexity of p53 modulation: Emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2973–2983. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golubovskaya V, Kaur A, Cance W. Cloning and characterization of the promoter region of human focal adhesion kinase gene: Nuclear factor kappa B and p53 binding sites*1. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Struct Expr. 2004;1678:111–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaller MD, Borgman CA, Cobb BS, Vines RR, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. pp125fak a structurally distinctive protein-tyrosine kinase associated with focal adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5192–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burridge K, Turner CE, Romer LH. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: A role in cytoskeletal assembly. J Cell Bio. 1992;119:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zachary I, Rozengurt E. Focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK): A point of convergence in the action of neuropeptides, integrins, and oncogenes. Cell. 1992;71:891–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90385-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lark AL, Livasy CA, Dressler L, et al. High focal adhesion kinase expression in invasive breast carcinomas is associated with an aggressive phenotype. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1289–1294. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean GW, Carragher NO, Avizienyte E, Evans J, Brunton VG, Frame MC. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer— A new therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:505–515. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Nimwegen MJ, van de Water B. Focal adhesion kinase: A potential target in cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;70:1330–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lark AL, Livasy CA, Calvo B, et al. Overexpression of focal adhesion kinase in primary colorectal carcinomas and colorectal liver metastases: Immunohistochemistry and real-time PCR analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baroni TE, Wang T, Qian H, et al. A global suppressor motif for p53 cancer mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4930–4935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Lh, Yang Xh, Bradham CA, et al. The focal adhesion kinase suppresses transformation-associated, anchorage-independent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. J Bio Chem. 2000;275:30597–30604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910027199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golubovskaya VM, Gross S, Kaur AS, et al. Simultaneous inhibition of focal adhesion kinase and SRC enhances detachment and apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:755–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith CS, Golubovskaya VM, Peck E, et al. Effect of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) downregulation with FAK antisense oligonucleotides and 5-fluorouracil on the viability of melanoma cell lines. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:357–362. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abernathy CR, Rasmussen SA, Stalker HJ, et al. NF1 mutation analysis using a combined heteroduplex/SSCP approach. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:548–554. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:6<548::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei CL, Wu Q, Vega VB, et al. A global map of p53 transcription-factor binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2006;124:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conway K, Edmiston SN, Cui L, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of p53 mutations associated with smoking in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1987–1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willis A, Jung EJ, Wakefield T, Chen X. Mutant p53 exerts a dominant negative effect by preventing wild-type p53 from binding to the promoter of its target genes. Oncogene. 2004;23:2330–2338. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]