Abstract

Iron-rich (ferruginous) ocean chemistry prevailed throughout most of Earth’s early history. Before the evolution and proliferation of oxygenic photosynthesis, biological production in the ferruginous oceans was likely driven by photoferrotrophic bacteria that oxidize ferrous iron {Fe(II)} to harness energy from sunlight, and fix inorganic carbon into biomass. Photoferrotrophs may thus have fuelled Earth’s early biosphere providing energy to drive microbial growth and evolution over billions of years. Yet, photoferrotrophic activity has remained largely elusive on the modern Earth, leaving models for early biological production untested and imperative ecological context for the evolution of life missing. Here, we show that an active community of pelagic photoferrotrophs comprises up to 30% of the total microbial community in illuminated ferruginous waters of Kabuno Bay (KB), East Africa (DR Congo). These photoferrotrophs produce oxidized iron {Fe(III)} and biomass, and support a diverse pelagic microbial community including heterotrophic Fe(III)-reducers, sulfate reducers, fermenters and methanogens. At modest light levels, rates of photoferrotrophy in KB exceed those predicted for early Earth primary production, and are sufficient to generate Earth’s largest sedimentary iron ore deposits. Fe cycling, however, is efficient, and complex microbial community interactions likely regulate Fe(III) and organic matter export from the photic zone.

Ferruginous water bodies are rare on the modern Earth, yet they are invaluable natural laboratories for exploring the ecology and biogeochemistry of Fe-rich waters extensible to the ferruginous oceans of the Precambrian Eons1,2,3,4. One modern ferruginous system, Lake Matano (Indonesia) hosts large populations of anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria implicated in photoferrotrophy due to the scarcity of sulfur substrates4. Low light levels and extremely slow growth rates, however, have precluded the direct measurement of photoferrotrophy in its water column5. In contrast, recent measurements of Fe-dependent carbon fixation reveal photoferrotrophy in Lake La Cruz (Spain) where photoferrotrophs have been enriched from the water column, but represent a minor fraction of the natural microbial community6. Inspired by the emerging evidence for photoferrotrophy in modern environments, we sought a photoferrotroph-dominated ecosystem that could be used to place constraints on the ecology of ancient ferruginous environments.

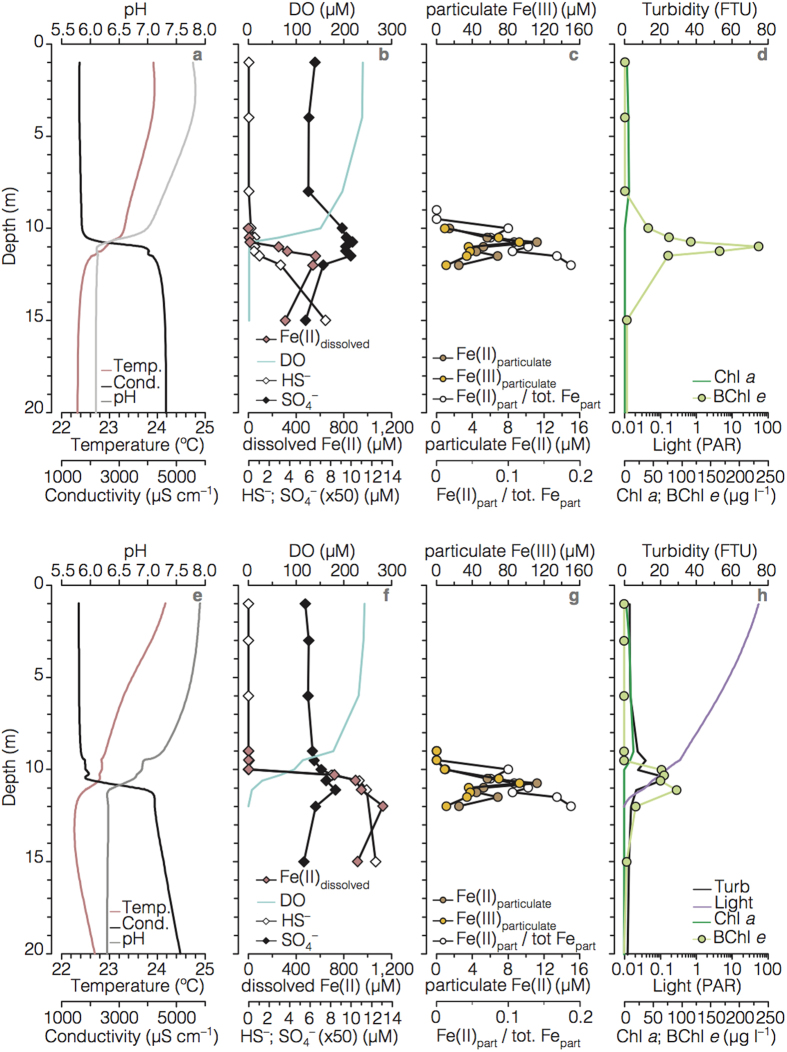

Kabuno Bay (KB) is a ferruginous sub-basin of Lake Kivu, situated in the heart of East Africa on the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda (Supplementary Fig. S1). Lake Kivu is of tectonic origin and is fed by deep-water inflows containing high concentrations of dissolved salts and geogenic gases7. KB is separated from the main basin of Lake Kivu by a shallow volcanic sill that restricts water exchange between the basins7. KB has a strongly stratified water column with oxic surface waters giving way to anoxic waters below about 10 m (Fig. 1a,b,e,f; Supplementary Fig. S2a,e)7. The deep anoxic waters of KB are iron-rich (Fe(II), 0.5M HCl extractable), containing up to 1.2 mM ferrous Fe {Fe(II)}, unlike the deep waters of Lake Kivu’s main basin, which contain abundant hydrogen sulfide (ca. 0.3 mM in deep waters)8. Fe(II)-rich hydrothermal springs with chemistry matching deep waters of KB are observed within the catchment basin9 (Supplementary Table S1), implicating hydrothermal Fe inputs to KB. Oxidation of upward diffusing Fe(II) generates both sharp gradients in dissolved Fe(II) concentration and an accumulation of mixed-valence Fe particles around the oxic-anoxic boundary (i.e., chemocline; Fig. 1b,c,f,g). Reduction of the settling particulate ferric Fe {Fe(III)} to Fe(II) partly closes the Fe-cycle (Fig. 1c,g).

Figure 1. Physical and chemical depth profiles from Kabuno Bay.

Data in the upper panels are from the rainy season (RS; February 2012) and lower panels from the dry season (DS; October 2012). (a,e) temperature (ºC), conductivity (μS cm−1), and pH; (b,f) dissolved oxygen (DO, μM), sulfide (HS−, μM), sulfate (SO4−, μM), and dissolved ferrous Fe (μM); (c,g) particulate ferrous Fe {Fe(II)} and ferric Fe {Fe(III)} (μM), and ratio of particulate Fe(II) with respect to total particulate Fe (i.e., particulate Fe(II)/[particulate Fe(II) + particulate Fe(III)]); (d,h) light (% PAR) and turbidity (FTU) profiles, and Chl a (μg l−1) and intercalibrated BChl e concentration (μg l−1) measured with multiparametric probes.

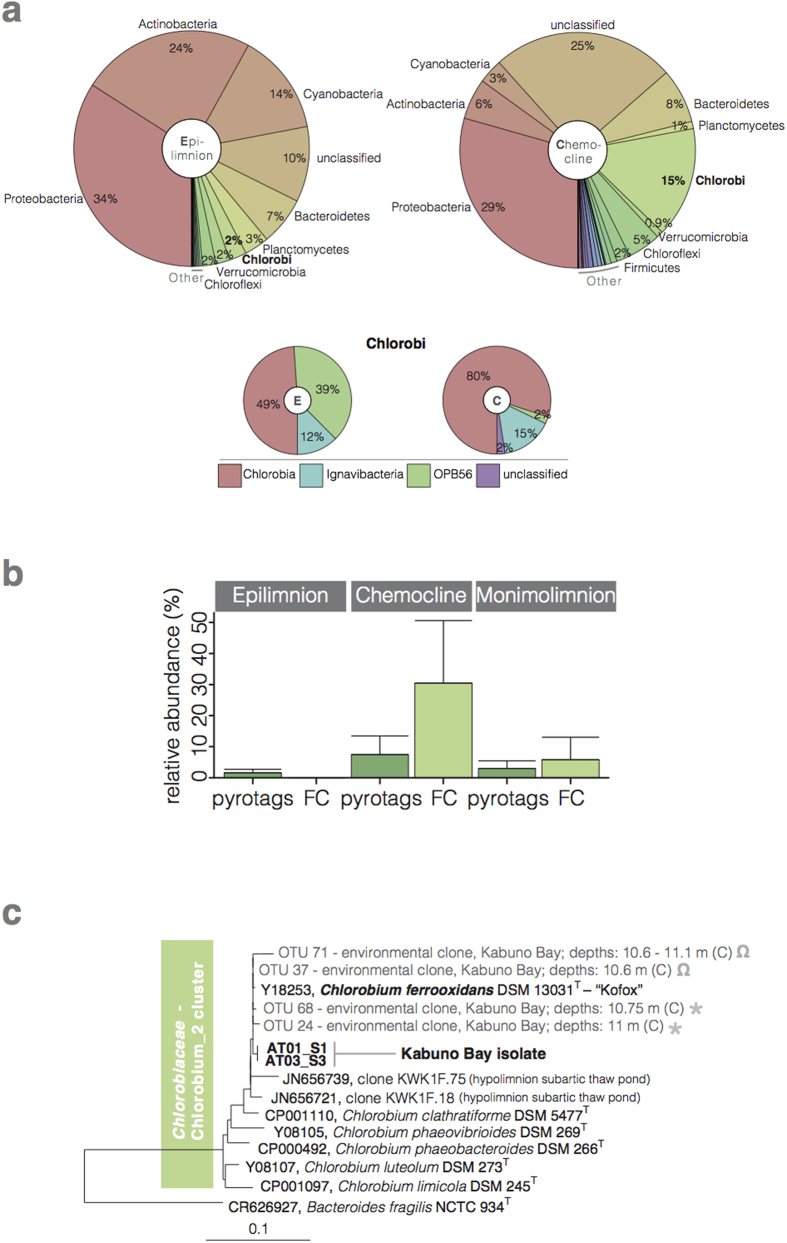

The physical and chemical stratification of the water column is also reflected in microbial community composition. In the oxic sunlit waters (between surface and 10.0 m depth), cyanobacteria (ca. 10% of total cell counts by flow cytometry), algae, and heterotrophic bacteria typical of freshwater environments10 dominate (Fig. 1d,h; Fig. 2a; Supplementary Table S2). Light, however, penetrates well below these surface waters illuminating the Fe(II)-rich anoxic waters below (Fig. 1d,h). Here, we find a very different microbial community (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. S2b,c,f,g). Anoxygenic photosynthetic green-sulfur bacteria (GSB) dominate in the chemocline where they comprise up to 30% of the total microbial community (Fig. 2b). Concentrations of Bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) e, a photosynthetic pigment utilized by brown-coloured, low light adapted GSB11,12 reach up to ca. 235 μg l−1 (Fig. 1d,h) and clearly delineate the distribution of GSB in the chemocline waters. Depth-integrated BChl e concentrations (130 mg m−2) are 10-fold higher than Chlorophyll (Chl) a (13 mg m−2) concentrations in the upper waters. Analysis of the 16S small subunit rRNA gene reveals that the GSB present in KB are closely related to Chlorobium (Chl.) ferrooxidans strain KoFox (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4). To date, str. KoFox is the sole member of the GSB known to conduct photoferrotrophy13 using Fe(II) as electron donor, and lacking the capacity to grow with reduced sulfur species13. Such physiology is consistent with the sub-μM concentrations (0–0.6 μM, maximum at 10.5 m; Fig. 1b,f) of reduced sulfur species observed in the illuminated waters of KB.

Figure 2. Microbial diversity in Kabuno Bay.

(a) Pie charts showing relative sequence abundances of retrieved bacterial phyla, with detailed hierarchy for the Chlorobi phylum, detected in epilimnetic (left, E), and chemocline (right, C) waters of KB. (b) Relative abundances of Chlorobi sequences (dark green) retrieved by pyrosequencing (pyrotags) and cell abundances (light green) determined by flow cytometry (FC) from KB water samples. (c) 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic tree of the Chlorobiaceae including representative OTUs (0.03 cut-off) from those depths with maximum relative abundances of GSB from both the rainy (RS; asterisk) and dry (DS; omega) season water samples, as well as full 16S rRNA gene sequences from the KB isolate. The identifier code for each OTU and the metadata describing the depths and the layers (E for epilimnion, C for chemocline, and M for monimolimnion) where sequences were recovered are also indicated.

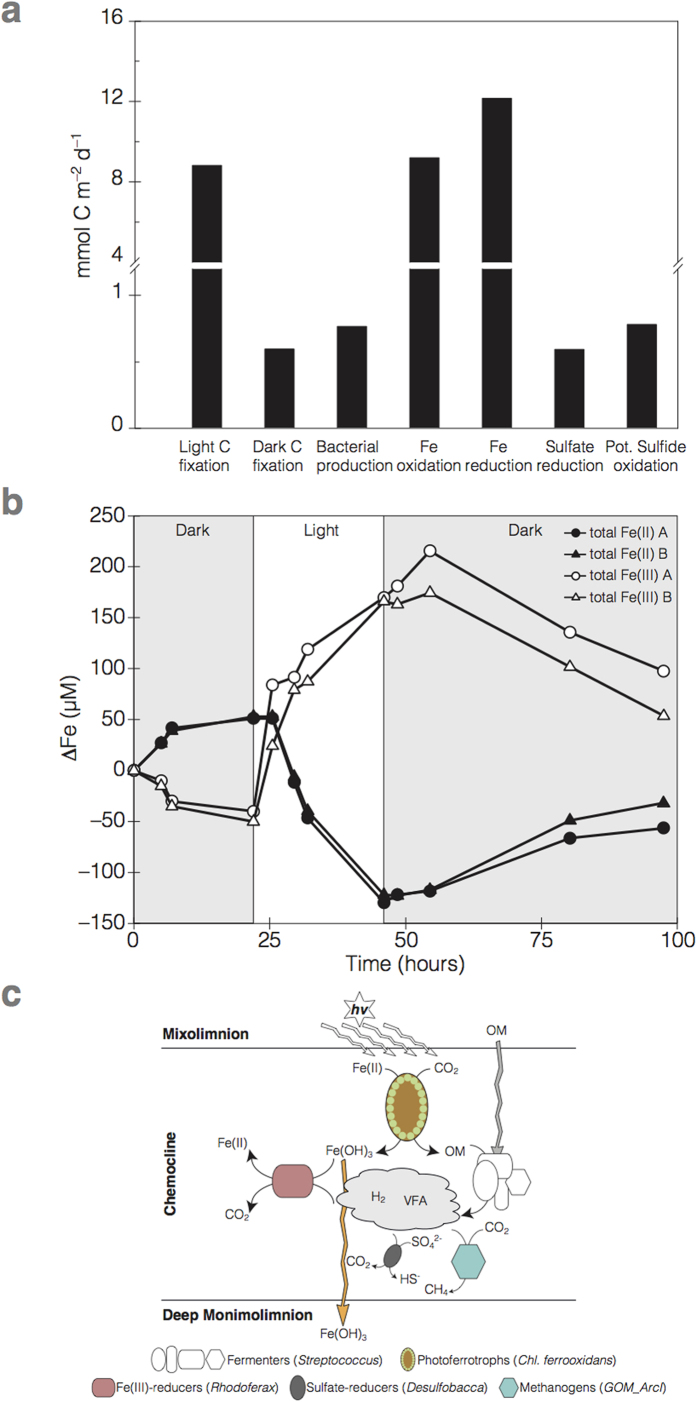

To directly test for photoferrotrophic activity in KB, we conducted a suite of incubation experiments in which rates of Fe(II) oxidation were measured over time. In the first set of experiments, we incubated water samples between 10.5 and 11.3 m by suspending triplicate glass incubation vessels directly in the water column so that the microbial community would experience near in situ light conditions with an average diel illumination of 0.6 μE m−2 s−1 and a mid-day maximum of 3.2 μE m−2 s−1. We measured light-dependant Fe(II) oxidation rates up to 100 μmol Fe l−1 d−1, demonstrating active photoferrotrophic activity in the KB chemocline (Fig. 3a). At 8 × 107 GSB cells l−1, cell specific Fe oxidation rates are up to 1.25 pmol cell−1 d−1. Depth-integrated Fe(II) oxidation rates of 36.8 mmol Fe m−2 d−1 were computed by taking the mean of the measured rates between 10.5 and 11.3 m, and multiplying by the 0.8 m interval. This Fe(II) oxidation could drive carbon (C) fixation at rates of 9.2 mmol C m−2 d−1 based on the expected (4:1) relationship between Fe oxidation to C-fixation during photoferrotrophy14; nearly the same rate (9 mmol C m−2 d−1) as measured directly by 13C labelling experiments. Rates of photosynthetic C fixation in the chemocline were up to 28% of the production in the oxic suface waters (32 mmol C m−2 d−1). While cyanobacteria and GSB co-occur in the chemocline, low average Chl a concentrations (ca. 1.1 μg l−1) and BChl e:Chl a ratios of more than about 100 highlight the dominance of GSB in the ferruginous waters. The importance of photoferrotrophy in the chemocline of KB is underscored by mass balance on the stable C isotope composition of particulate organic matter. Using a simple isotope-mixing model (Supplementary Information) we estimated that 74% ± 13% of the particulate organic carbon pool in the chemocline is derived through anoxygenic photosynthesis by GSB, with a maximum (89%) at 11.25 m. This mass balance reveals that GSB constituted 208 mmol m−2 biomass, which together with the light-dependent C fixation rates translates to a GSB biomass turnover time of 23 d.

Figure 3. Process rates in Kabuno Bay chemocline.

(a) depth integrated rates (Carbon normalized; mmol C m−2 d−1) of: light and dark C fixation; bacterial production (as 3H-Thymidine incorporation); Fe oxidation and reduction; sulfate reduction; and potential sulfide oxidation from in situ measurements conducted in KB. (b) total Fe(II) (black) and total Fe(III) (white) concentrations over time from duplicate vessels incubated ex situ through a light (white background) and dark (light grey background) cycle. (c) proposed metabolic model for Fe and C cycling in ferruginous waters; legend: hv, sunlight; VFA, volatile fatty acids; OM, organic matter.

Fe(III) reduction rates measured in glass vessels kept dark and incubated alongside the light vessels are nearly equivalent (48 mmol m−2 d−1) to Fe(II) oxidation rates, suggesting a tightly coupled, pelagic Fe-cycle driven by photoferrotrophy, with comparably little net Fe oxidation. Sulfate reduction and potential sulfide oxidation also occurred, but these S-based metabolisms proceed at rates much lower than Fe-reduction and oxidation, respectively (Fig. 3a). This implies that sulfide produced during sulfate reduction plays a small role in reduction of Fe, and most Fe reduction is likely heterotrophic. Fe reduction driven by GSB biomass breakdown is likely reflected by bacterial production rates, which were highest in the illuminated ferruginous waters of the chemocline (Supplementary Fig. S2d). Photoferrotrophy therefore appears to support much of the biogeochemical cycling in the KB chemocline, with primary production of organic matter driving heterotrophic microbial Fe(III) reduction. The rapid GSB turnover rates estimated through our stable isotope mass balance also indicate the effective breakdown of GSB biomass implying that fermentation of this biomass provides substrates (e.g., CH3COO−, H2) to fuel Fe reduction, and possible pelagic heterotrophy with other electron acceptors such as sulfate, or methanogenesis. Both CH3COO− and H2 can be detected in the KB water column (Fig. S2e).

To more directly test the potential for pelagic Fe cycling, the microbial community was also subjected to alternating light and dark conditions in a second incubation experiment conducted ex situ with an inhibitor of oxygenic photosynthesis15 (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea; DCMU; 0.55 mg l−1; Fig. 3b) and at light intensities known to support maximum Fe oxidation rates by Chl. ferrooxidans str. KoFox (15 μE m−2 s−1). These ex situ Fe(II) oxidation rates are similar to in situ rates (115 μmol l−1 d−1; Fig. 3b), and at 9 × 107 GSB cells l−1 in this experiment translate to 1.3 pmol cell−1 d−1. Fe(III) reduction rates, in contrast, are much lower (44 μmol l−1 d−1; Fig. 3b), allowing net Fe(II) oxidation of 71 μmol l−1 d−1 and Fe(III) accumulation (Fig. 3b). These measurements demonstrate that Fe(II) oxidation can outpace the reactions, like fermentation, that degrade GSB biomass and ultimately lead to Fe(III) reduction.

We also isolated the dominant GSB from the water column into axenic culture. Analyses of the small subunit 16S rRNA gene sequence from the axenic culture reveal that the KB GSB isolate is closely related (98.7% of sequence similarity) to Chl. ferrooxidans str. KoFox (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S4) and clusters with the dominant Chlorobii 16S rRNA gene sequences recovered from the KB water column. Unlike str. KoFox though, which only grows in co-culture13, the KB strain grows in a pure culture. Str. KB is clearly adapted to pelagic growth under low light conditions synthesizing BChl e pigments rather than BChl c as does str. KoFox13, which was isolated from the surface of shallow creek sediments13. Detailed pigment analyses show low-light adaptations in KB strain’s light harvesting apparatus, including high abundances of higher alkylated BChl e homologs and a lack of the first BChl e homolog (Supplementary Fig. S5). These adaptations may be essential for photoferrotrophy under the low light conditions (Fig. 1h) encountered in ferruginous water columns11,16. Incubation experiments with the KB isolate also demonstrate its capacity to grow photoferrotrophically under low light conditions (i.e., 0.64 μE m−2 s−1) oxidizing Fe at a rate of 1.4 mmol l−1 d−1 (Supplementary Fig. S6).

As primary producers in the KB chemocline, photoferrotrophic GSB play a key role supporting and shaping the resident microbial community. This community is taxonomically and functionally diverse with common diversity metrics indicating nearly 3,000 estimated species (Supplementary Table S3), which is comparable to typical modern coastal marine waters or oxygen-minimum zones17,18. This community is comprised of known heterotrophic Fe(III)-reducers19 with members of the Rhodoferax genera making up 8% of the OTUs (operational taxonomic units) retrieved. Other community members include micro-aerophillic Fe(II)-oxidizers, sulfate reducers (e.g., Desulfobacca, Desulfomonile), fermenters (e.g., Streptococcus), methanotrophs (e.g., Methylobacterium), and methanogens (e.g., Methanosaeta, GOM_ArcI), as well as an appreciable fraction (>13%) of taxa belonging to phyla lacking cultured representatives (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 2a). Anoxygenic phototrophs in addition to the 15% GSB, include purple sulfur bacteria and Chloroflexi, but these combined never exceed 9% of the OTUs retrieved (Fig. 2a). The archaeal community is dominated by methanogens suggesting pelagic methanogenic activity in these ferruginous waters (Supplementary Fig. S2c,g). Overall, the most abundant taxa in the chemocline are involved in C cycling linked to the oxidation and reduction of Fe, but other members almost certainly play key roles in microbial community metabolism and biogeochemical cycling. For example, the presence of sulfate reducers and methanogens directly in the KB water column implies that some organic matter degradation is channelled through sulfate reduction and methanogenesis, thereby escaping remineralization through Fe reduction. By extension, this also requires that some Fe(III) escapes reduction, perhaps through aging and recrystallization to forms less available towards Fe reduction20, for subsequent export to underlying sediments. Mixed valence Fe particles at the base of the chemocline indeed are comprised of 20% Fe(II) and 80% Fe(III) (mean redox state of 2.8, Fig 1c), demonstrating the export of ferric iron from the photic zone.

Our observations from KB provide possible insight into the structure and functioning of ancient photoferrotrophic microbial communities thought to have sustained the global C-cycle prior to the evolution and proliferation of oxygenic phototrophs. Rates of photoferrotrophy in the KB water column (3.4 mol C m−2 yr−1) are within the range of those modelled for global photoferrotrophic production in Earth’s early ferruginous oceans (1.4 mol m−2 yr−1 based on 5 × 1014 mol C yr−1 and an ocean area of 3.6 × 1014 m2)21. Previous computations also suggest Fe deposition rates of up to 45 mol m−2 yr−1 were needed to deposit the largest Precambrian banded iron formations (BIFs)22. Net Fe oxidation rates of 0.8 pmol cell−1 d−1 in KB show that for a photic zone depth of 100 m, photoferrotrophic GSB at low cell densities of 1.7 × 103 cells ml−1 could produce up to 50 mol m−2 yr−1 Fe(III) under modest light conditions, enough to deposit even the largest BIF (i.e., Hammersley Basin; Australia)22. Notably, the mean redox state of 2.8 for mixed valence Fe particles exported from the KB photic zone is sufficiently oxidized to explain the Fe(III) component in many BIFs, which have an average Fe redox state of 2.423. In KB, pelagic Fe(III) reduction results from microbial community metabolism illustrating the importance of considering net Fe(II) oxidation rates in photoferrotrophic models of BIF deposition. Photoferrotrophic deposition of BIF then likely requires that rates of Fe(II) oxidation outpace processes like fermentation that ultimately lead to pelagic Fe(III) reduction. Our observations implicate complex interactions between microbial community metabolism and physical and chemical dynamics in the regulation of C and Fe export from ferruginous euphotic zones, but the quantitative nature of these interactions remains uncertain for now. Future work at KB and in other ferruginous water bodies will help tease apart these interactions, and elucidate the microbial controls on biogeochemical cycling in modern and ancient ferruginous waters.

Methods Summary

Water samples from the water column of Kabuno Bay (1.58º–1.70º S, 29.01º–29.09º E; DR Congo) were collected in February (rainy season, RS) and October (dry season, DS) 2012 and processed for physico-chemical characteristics, microbial abundance, diversity, activity, and cultivation of green sulfur bacteria. Vertical CTD (conductivity, temperature, depth) profiles were measured in situ with two multiparametric probes (Hydrolab DS5, OTT Hydromet, Germany; and Sea & Sun CTD90, Sea and Sun Technology, Germany). Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) was measured using a submersible Li-Cor LI-193SA spherical quantum sensor (Lincoln, NE, USA). pH, CH4 (methane) concentrations, and stable C isotopic composition (δ13C) of particulate organic carbon (POC; δ13C-POC) were measured as previously described24,25. Bacterial production was estimated from tritiated thymidine (3H-Thymidine) incorporation rates25,26. Bulk light and dark inorganic C fixation was measured by NaH13CO3 incorporation (see supplementary methods for description). Fe speciation was measured using the ferrozine method27, while Fe oxidation and reduction rates were determined following changes in Fe speciation over time. Sulfate reduction rates were determined by using the 35S radiotracer method28. Photosynthetic pigments were analysed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography according to29,30. Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described31 and further subjected to pyrosequencing32. Chlorobi enrichment cultures were generated by supplementing water with nutrients and Fe. Isolates were obtained through multiple serial dilutions in a defined mineral media33. Small aliquots from the isolates were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the 16S rRNA gene, and PCR products sequenced. All Chlorobi-retrieved 16S rRNA gene sequences were analysed by means of ARB34 loaded with a SILVA 16S rRNA compatible database.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Llirós, M. et al. Pelagic photoferrotrophy iron cycling in a modern ferruginous basin. Sci. Rep. 5, 13803; doi: 10.1038/srep13803 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Georges Alunga, Pascal Masilya, Pascal Mwapu Ishumbisho, Boniface Kaningini, Charles Balagizi, Katcho Karume, Mathieu Yalire, Djoba, Silas, Laetitia Nyinawamwiza, Bruno Leporcq, Adriana Anzil, Marc-Vincent Commarieu, Fleur A E Roland, Laetitia Montante, Alexander Treusch and Niko Finke for help with laboratory and field work. This work was partially supported by Belgian (FNRS 2.4.515.11 and BELSPO SD/AR/02A contracts), Danish (grant no. DNRF53 to DEC), and European (grant no. ERC-StG 240002, for stable isotope measurements) funds. AVB is a senior research associate at the FRS-FNRS. SAC was supported by the Agouron institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions S.A.C., A.V.B., F.D. and M.L.l. conceived research; M.L., A.V.B., S.A.C., F.D., J.–P.D., T.G.–A., Ö.I. and C.M. collected and analyzed samples; M.L., T.G.–A., Ö.I. and X.T.–M. conducted gene sequence analyses; S.A.C. isolated the Kabuno Bay strain and conducted Fe oxidation and reduction rate measurements; C.M. and F.D. conducted C-fixation rate measurements; M.L., S.A.C., F.D., C.M., A.V.B., X.T.–M., C.M.B., S.B., T.G.–A., Ö.I., P.S. and D.E.C. analyzed the data; M.L. and S.A.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

References

- Poulton S. W. & Canfield D. E. Ferruginous conditions: a dominant feature of the ocean through Earth's History. Elements 7, 107–112 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Planavsky N. J. et al. Widespread iron-rich conditions in the mid-Proterozoic ocean. Nature 477, 448–451 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland H. D. in Treatise on Geochemistry (eds. Holland H. D. & Turekian K. K.) 6, 583–625 (Elsevier, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Crowe S. A. et al. Photoferrotrophs thrive in an Archean Ocean analogue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 15938–15943 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe S. A. et al. Deep-water anoxygenic photosythesis in a ferruginous chemocline. Geobiology 12, 322–339 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter X. A. et al. Phototrophic Fe(II)-oxidation in the chemocline of a ferruginous meromictic lake. Front. Microbiol . 5, 1–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degens E. T. & Kulbicki G. Hydrothermal origin of metals in some East African rift lakes. Mineral Deposita 8, 388–404 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Pasche N., Dinkel C., Müller B., Schmid M. & Wehrli B. Physical and biogeochemical limits to internal nutrient loading of meromictic Lake Kivu. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1863–1873 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tassi F. et al. Water and gas chemistry at Lake Kivu (DRC): Geochemical evidence of vertical and horizontal heterogeneities in a multibasin structure. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 10, 1–22 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. J., Jones S. E., Eiler A., Mcmahon K. D. & Bertilsson S. A guide to the natural history of freshwater lake bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 14–49 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego C. M. & Garcia-Gil L. J. Rearrangement of light harvesting bacteriochlorophyll homologues as a response of green sulfur bacteria to low light intensitie. Photosynth. Res. 45, 21–30 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego C. M. et al. Distribution of bacteriochlorophyll homologs in natural populations of brown-colored phototrophic sulfur bacteria. 24, 301–309 (1997).

- Heising S., Richter L., Ludwig W. & Schink B. Chlorobium ferrooxidans sp. nov., a phototrophic green sulfur bacterium that oxidizes ferrous iron in coculture with a ‘Geospirillum’ sp. strain. Arch. Microbiol. 172, 116–124 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdel F., Schnell S., Heising S. & Ehrenreich A. Ferrous iron oxidation by anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Nature 362, 834–836 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen B. B., Kuenen J. G. & Cohen Y. Microbial transformations of sulfur compounds in a stratified lake (Solar Lake, Sinai). Limnol. Oceanogr. 24, 799–822 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Kappler A., Pasquero C., Konhauser K. O. & Newman D. K. Deposition of banded iron formations by anoxygenic phototrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria. Geology 33, 865–868 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Stewart F. J., Ulloa O. & DeLong E. F. Microbial metatranscriptomics in a permanent marine oxygen minimum zone. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 23–40 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa O., Wright J. J., Belmar L. & Hallam S. J. in The Prokaryotes (eds. Rosenberg E., DeLong E. F., Lory S., Stackebrandt E. & Thompson F.) 113–122 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Finneran K. T., Johnsen C. V. & Lovley D. R. Rhodoferax ferrireducens sp. nov., a psychrotolerant, facultatively anaerobic bacterium that oxidizes acetate with the reduction of Fe(III). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 669–673 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden E. E. Fe(III) oxide reactivity toward biological versus chemical reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 1319–1324 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D. E., Rosing M. T. & Bjerrum C. Early anaerobic metabolisms. Philos T Roy Soc B 361, 1819–1836 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konhauser K. O. et al. Could bacteria have formed the Precambrian banded iron formations? Geology 30, 1079–1082 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Klein C. & Beukes N. J. in The Proterozoic Biosphere (eds. Schopf J. W. & Klein C.) 139–146 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Borges A. V., Abril G., Delille B., Descy J.-P. & Darchambeau F. Diffusive methane emissions to the atmosphere from Lake Kivu (Eastern Africa). J. Geophys. Res. 1–15 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Borges A. V. et al. Carbon cycling of Lake Kivu (East Africa): net autotrophy in the epilimnion and emission of CO2 to the atmosphere sustained by geogenic inputs. PLoS ONE 9, e109500 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman J. A. & Azam F. Thymidine incorporation as a measure of heterotrophic bacterioplankton production in marine surface waters: Evaluation and field results. Mar. Biol. 66, 109–120 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Viollier E., Inglett P. W., Hunter K., Roychoudhury A. N. & Van Cappellen P. The ferrozine method revisited: Fe(II)/Fe(III) determination in natural waters. Appl. Geochem. 15, 785–790 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Fossing H. & Jørgensen B. B. Measurement of bacterial sulfate reduction in sediments – Evaluation of a single-step Chromium reduction method. Biogeochemistry 8, 205–222 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Descy J.-P., Higgins H. W., Mackey D. J., Hurley J. P. & Frost T. M. Pigment ratios and phytoplankton assessment in northern Wisconsin lakes. J. Phycol. 36, 274–286 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Borrego C. M. & Garcia-Gil L. J. Separation of bacteriochlorophyll homologues from green photosynthetic sulfur bacteria by reversed-phase HPLC. Photosynth. Res. 41, 157–164 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llirós M., Casamayor E. O. & Borrego C. M. High archaeal richness in the water column of a freshwater sulfurous karstic lake along an interannual study. 66, 331–342 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shah V. et al. Bacterial and archaea community present in the Pine Barrens Forest of Long Island, NY: unusually high percentage of ammonia oxidizing bacteria. PLoS ONE 6, e26263 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegler F., Posth N. R., Jiang J. & Kappler A. Physiology of phototrophic iron(II)-oxidizing bacteria: implications for modern and ancient environments. 66, 250–260 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ludwig W. et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1363–1371 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.