Abstract

Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) are the major downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway, which regulates tissue homeostasis, organ size, regeneration and tumorigenesis. In this Progress article, we summarize the current understanding of the biological functions of YAP and TAZ, and how the regulation of these two proteins can be disrupted in cancer. We also highlight recent findings on their expanding role in cancer progression and describe the potential of these targets for therapeutic intervention.

The Hippo pathway was initially identified and named through screenings for mutant tumour suppressors in flies, in which loss-of-function mutations of components of the Hippo pathway revealed robust overgrowth as a result of increased cell proliferation and decreased cell death1. The observation that this pathway — and its role in cell proliferation — is conserved in mammals spurred great anticipation and has sustained immense interest in recent years as experimental evidence has shown that the Hippo pathway is strongly involved in several processes of cancer progression and, in general, has important regulatory functions in organ development, regeneration and stem cell biology2–4.

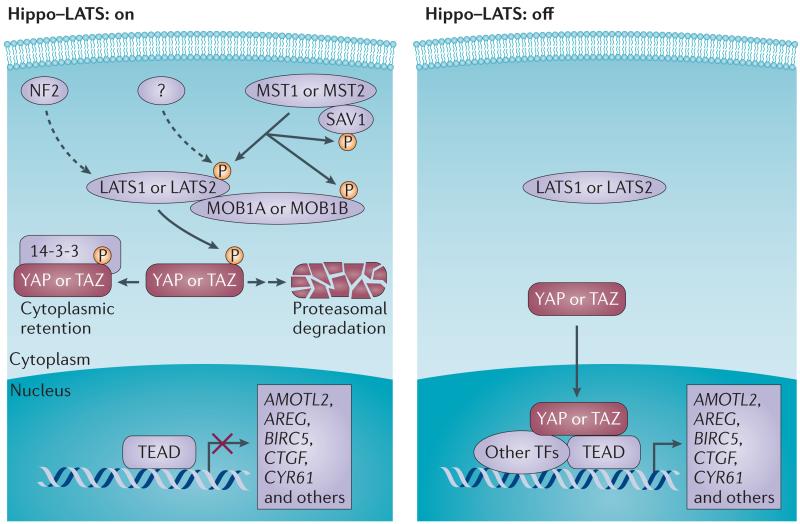

The central components of this pathway comprise a regulatory serine-threonine kinase module and a transcriptional module. The kinase module includes the mammalian orthologues of Drosophila melanogaster Hippo, mammalian STE20-like protein kinase 1 (MST1; also known as STK4) and MST2 (also known as STK3), and in addition, the large tumour suppressor 1 (LATS1) and LATS2 (REF. 1) (FIG. 1). The transcriptional module includes yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ; also known as WWTR1), which are two closely related paralogues that largely mediate the downstream effects of Hippo signalling1. YAP and TAZ predominantly show functional redundancy; genetic evidence in mice clearly shows their redundant roles in development5 and regeneration6, as the dual depletion of YAP and TAZ generally results in a more severe phenotype than either single mutation7. YAP and TAZ function as transcriptional co-activators that shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, where they induce expression of cell-proliferative and anti-apoptotic genes via interactions with transcription factors, particularly TEA domain family members (TEAD)3. When the inhibitory Hippo kinase module is ‘on’, LATS1 and LATS2 phosphorylate and inactivate YAP and TAZ, and the output gene production is therefore turned off. By contrast, when the kinase module is ‘off’, hypophosphorylated YAP and TAZ translocate into the nucleus and induce target gene expression4. In this classic view, the components of the kinase module are tumour suppressors and those of the transcriptional module are oncogenes.

Figure 1. Regulation of YAP and TAZ.

The core inhibitory kinase module is composed of two groups of kinases, the mammalian STE20-like protein kinase 1 (MST1) and MST2, and the large tumour suppressor 1 (LATS1) and LATS2, in combination with their activating adaptor proteins, salvador family WW domain-containing protein 1 (SAV1), MOB kinase activator 1A (MOB1A) and MOB1B. The transcriptional module is composed of the transcriptional co-activators yes-associated protein (YAP) and its paralogue, transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), and the TEA domain family members (TEAD1–TEAD4). When the upstream kinase module is activated, LATS1 and LATS2 phosphorylate YAP and TAZ, which leads to inhibition of the transcriptional activity through 14-3-3-mediated cytoplasmic retention of YAP and TAZ priming them for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation1,3. Neurofibromin 2 (NF2) is an additional and potent activator of LATS1 and LATS2 (indicated by the dashed arrow) but is devoid of kinase activity. A yet unidentified kinase (or several of them) may directly phosphorylate LATS1 and LATS2 on the key activation site(s) in a MST1- and MST2-independent manner (indicated by the dashed arrow); when this site is not phosphorylated, the Hippo–LATS pathway is ‘off’. When YAP and TAZ are not phosphorylated by LATS kinases, they translocate to the nucleus and bind to sequence specific transcription factors TEAD1–TEAD4 (and other transcription factors, such as SMAD, RUNX, TP73, TBX5 and PAX), which enables the transcription of target genes encoding proteins that are involved in cell proliferation and survival1,3. AMOTL2, angiomotin-like protein 2; AREG, amphiregulin; BIRC5, baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 5; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; CYR61, cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61; TF, transcription factor.

In recent years, the complexity of YAP and TAZ regulation has expanded considerably, with the identification of more regulatory components and with evidence showing that the Hippo pathway is inter-linked with other cancer-relevant pathways, especially G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and WNT pathways. This highlights that the field is moving away from the idea of a simple linear pathway to a view in which YAP and TAZ are an integral part and a nexus of a network composed of multiple signalling pathways.

In this Progress article, we summarize the latest findings regarding the expanding roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer, discuss the different ways in which the regulation of these proteins is disrupted and describe their potential as therapeutic targets.

Regulation of and by YAP and TAZ

Regulation through the microenvironment

YAP and TAZ are regulated by soluble extracellular factors, cell–cell adhesions and mechanotransduction3. Therefore, this pathway is capable of sensing and responding to the physical organization of cells, coordinating these physical signals with chemical cues and ultimately functioning as an integrator and a nexus for both dynamic short-term and long-term regulation of cellular signalling.

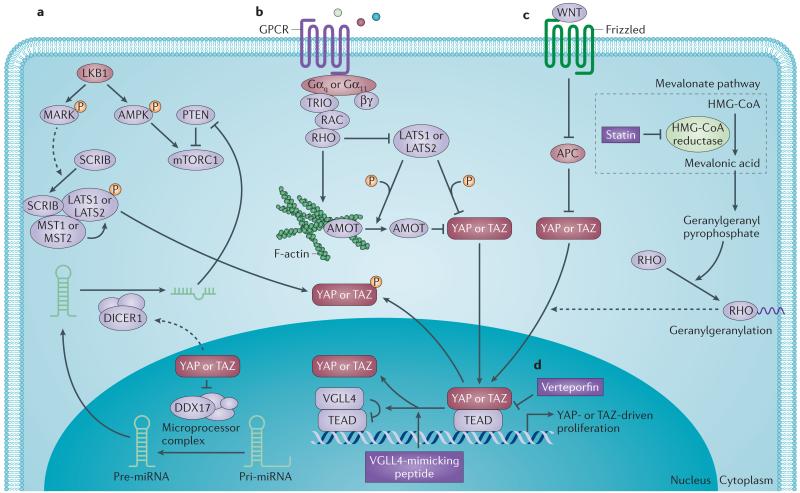

Tumour cells generate niches that are different to those found in non-neoplastic tissues. YAP and TAZ regulate these niches by modulating cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions8 and the production of secretory proteins, such as amphiregulin (AREG; an epidermal growth factor (EGF) family member)9, cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)3,10. In addition, YAP and TAZ are also directly regulated by the extracellular matrix (ECM)8,11,12, which is itself stiffened in tumours, partly as a result of enhanced integrin signalling13. Cells grown on high ECM stiffness show high nuclear localization and subsequent transcriptional activity of YAP and TAZ, whereas in cells that are grown on low stiffness substrates, YAP and TAZ translocate to the cytoplasm and are inactivated11,12,14. This regulation requires RHO GTPase activity and tension of the actomyosin cytoskeleton but is apparently independent of the Hippo–LATS cascade8,12; however, other reports have shown that mechanotransduction also includes regulation of YAP and TAZ phosphorylation by LATS kinases15,16. How actin regulates YAP and TAZ is thus unclear but the small GTPase RHO functions as a prime regulator of this actin dependency12,15,17 (FIG. 2). Angiomotin (AMOT) is a filamentous actin (F-actin)-binding protein that predominantly localizes to cellular junctions18. AMOT binds and sequesters YAP and TAZ in the cytoplasm, regardless of the phosphorylation status of YAP and TAZ18 (FIG. 2b). Interestingly, recent studies revealed that AMOT is phosphorylated by LATS kinases, which potentiates its inhibitory effects on YAP and TAZ activity19. LATS kinases thereby inhibit YAP and TAZ nuclear activity by two different means.

Figure 2. Pathway crosstalks regulate YAP and TAZ.

Regulation of yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) activity goes well beyond the core kinases in the Hippo pathway. a | The liver kinase B1 (LKB1)–microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK) pathway inhibits YAP and TAZ through scribble homologue (SCRIB)-mediated activation of mammalian STE20-like protein kinase 1 (MST1), MST2, large tumour suppressor 1 (LATS1) and LATS2. LKB1 tumour suppressor directly phosphorylates and activates substrates of the MARK family kinases to induce membrane localization of the basolateral polarity complex containing SCRIB47. This relocalization of SCRIB activates the MST–LATS canonical Hippo kinase cascade to induce phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of YAP and TAZ47. LKB1 also regulates the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to confer its tumour suppressor function46. In addition, YAP and TAZ inhibition mediated by the LKB1–MARK pathway can suppress mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) function by restricting the transcription of micro-RNA 29 (miR-29)48, which inhibits the translation of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), an upstream negative regulator of mTOR. b | Gαq- and Gα11-coupled receptor signals activate YAP and TAZ through RHO and/or RAC-regulated signalling circuitry. Cancer-associated Gαq and Gα11 mutants activate RHO to inhibit LATS through actin cytoskeleton reorganization, resulting in dephosphorylation and activation of YAP50. Gαq also stimulates triple functional domain protein (TRIO)–RHO and TRIO–RAC signalling to promote actin polymerization, which causes the dissociation of angiomotin (AMOT)–YAP complexes through AMOT binding to filamentous actin (F-actin), thereby contributing to YAP nuclear translocation49. Phosphorylation of AMOT by LATS prevents AMOT binding to F-actin, which potentiates its inhibitory effects on YAP and TAZ activity19. c | YAP and TAZ are transcriptionally inactivated by the tumour suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC). WNT stimulation or loss of APC causes YAP and TAZ nuclear localization and activation of YAP–TEA domain family member (TEAD)-dependent and TAZ–TEAD-dependent transcription23. d | Inhibitors that suppress YAP and TAZ function. Verteporfin abrogates the interaction between YAP and TEAD, thus inhibiting YAP-induced transcription42. Vestigial-like family member 4 (VGLL4) directly competes with YAP in binding to TEAD58, and a peptide mimicking this function of VGLL4 is capable of functioning as a YAP antagonist59. The mevalonate cholesterol biosynthesis pathway provides a source of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, which is required for membrane localization and activation of RHO GTPases. Inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase) by statins reduces the geranylgeranylation and membrane localization of RHO GTPases, restricting YAP and TAZ nuclear accumulation and thus activity60. DDX17, DEAD box helicase 17; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor.

The relationship between YAP and TAZ activity and the ECM provides a feedforward mechanism in which cancer cells drive extracellular stiffening that further activates YAP and TAZ, and these transcriptional co-activators are therefore not only responders but also direct mediators of mechanical signals8,14.

Regulation via extracellular signalling

The Hippo pathway does not seem to have a unique extracellular ligand that exclusively regulates this pathway. Instead, a general role of GPCRs as potent regulators of Hippo signalling has recently been revealed17. GPCRs function as key transducers of extracellular signals to the interior of the cell by using hetero trimeric G proteins that consist of α-, β- and γ-subunits20. Among the Gα proteins, Gα11, Gα12, Gα13, Gαi , Gαo and Gαq can activate YAP and TAZ, whereas Gαs-coupled signals repress them17. These regulatory effects are mediated by LATS kinases; when a GPCR activates RHO GTPase, it subsequently induces F-actin formation to inhibit LATS kinase activity in a MST-independent manner17 (FIG. 2b).

In addition to GPCRs, the cytokine receptor leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) can also activate the Hippo kinase module21, as can epidermal growth factor (EGF), which dissociates the Hippo kinase complex thereby activating YAP and TAZ22. Furthermore, other signalling pathways — such as WNT23–27, TGFβ10,28,29 and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)29 — also potentiate YAP and TAZ activity30. WNT stimulation diverts YAP and TAZ away from the β-catenin destruction complex, causing β-catenin stabilization as well as YAP and TAZ nuclear accumulation23. TAZ interacts with TGFβ-regulated SMAD2 and SMAD3 controlling their nuclear localization and driving transcription28. YAP can also engage with SMAD1 and synergize the transcriptional activity downstream of BMP signalling29.

Regulation of microRNA biogenesis

MicroRNA (miRNA) suppression has been proposed to promote tumorigenesis31. The processing and biogenesis of miRNAs require stepwise cleavage of long primary miRNA transcripts (pri-miRNA) by the microprocessor and DICER complexes to generate mature mi RNAs that repress expression of target mRNAs. Recent data suggest that YAP induces widespread miRNA repression by modulating the microprocessor complex machinery in a cell density-dependent but apparently TEAD-independent manner32 (FIG. 2). At low cell density, YAP is localized in the nucleus33, where it represses miRNA biogenesis by binding and sequestering DEAD box helicase 17 (DDX17) from other members of the microprocessor complex32. At high cell density, the Hippo pathway-mediated cytoplasmic retention of YAP allows DDX17 to associate with the microprocessor complex, resulting in enhanced miRNA biogenesis. Furthermore, in YAP-induced mouse models of squamous cell and hepatic carcinoma, the levels of several mi RNAs were decreased, whereas levels of pri-mi RNAs were increased32, which suggests an important role of miRNA biogenesis in YAP-induced tumorigenesis. Intriguingly, Chaulk et al.34 reported that nuclear YAP and TAZ induce the activity of the DICER complex, therefore suggesting that nuclear YAP and TAZ can mediate the processing of specific pre-miRNAs to mature miRNAs in some instances34. Therefore, in some contexts, YAP and TAZ have opposite roles in miRNA biogenesis. The biological regulation and the mechanisms for these differing phenomena are currently not well understood32,34.

Oncogenic roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer

Hyperactivation of YAP and TAZ is widespread in cancers2,4, and reports of gene amplification and epigenetic modulation of the YAP and TAZ loci in cancer are similarly prevalent, which implies that YAP- and TAZ-mediated transcriptional activity is important for the development and sustainability of neoplasia2,4.

Importantly, studies have revealed that the correlation between YAP and TAZ amplification and transcriptional activity is functionally relevant. Inactivation of the transcriptional module (FIG. 1) in a variety of cancer models — including cell lines, xenografts, transgenic mouse models and flies — reverts principal cancer features such as cancer stem cell properties3,35–38, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)36, increased migration39 and resistance to anoikis15 (apoptosis induced by insufficient attachment of cells to a substrate) and increased potential for metastasis39. Furthermore, induced expression of YAP and TAZ can trigger transition of normal epithelial cells into metastatic cells via EMT21,35,36,39 and can confer stem cell characteristics35,38. Interestingly dedifferentiation of adult hepatocytes into progenitor cells was reported upon transient inducible YAP expression38. In addition, TAZ, but not YAP, was shown to promote lineage switching from luminal to basal mammary epithelial cells37 and to confer cancer stem cell features to breast cancer cells36. These results highlight not only the potential of YAP and TAZ as effectors in stem cell biology but also the differences in regulation between YAP and TAZ depending on the tissue type. Intriguingly, separate YAP and TAZ ablation in the mouse kidney yields distinct phenotypes; YAP loss leads to the development of dysplastic kidneys, whereas depletion of TAZ results in cystic kidneys40. Importantly, additional ablation of TAZ shows no exacerbation of the glomeruli phenotype in YAP-mutant kidneys, indicating their distinct roles during nephrogenesis40. Although YAP and TAZ predominantly show functional redundancy7, this divergence adds an extra level of complexity and a conceivable level of dynamic regulation to the Hippo pathway in different tissues, but how this interplay and distinct regulation happens is currently not well understood.

Oncogenic activation of YAP and TAZ

Given the fact that the Hippo pathway is a prime regulator of cancer pathology, a major conundrum in the field has been the lack of germline or somatic mutations identified in components of the pathway in neoplastic tissues, except for neurofibromin 2 (NF2; also known as Merlin) in neurofibromatosis and malignant mesothelioma, and LATS2 in malignant mesothelioma2,4. NF2 activates the core inhibitory Hippo kinase module under normal circumstances (FIG. 1) and loss of NF2 therefore causes hyperactivation of YAP and TAZ41. Importantly, predisposition for neoplasia by NF2 loss is mediated by the activation of YAP, as genetic and pharmacological inhibition of YAP prevents the neoplastic phenotype in Nf2-mutant mice41,42.

KRAS mutations

Activating mutations in KRAS frequently occur in diverse human carcinomas and are particularly prominent in those of the pancreas, lung and colon. Recent data revealed that YAP is essential for the neoplastic progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in Kras-mutant mice43. In addition, YAP is required for tumour recurrence in the absence of KRAS in Kras-driven murine models of both PDAC44 and lung cancer45, implying the need for combinatorial YAP inhibition in some tumours that are treated with drugs targeting KRAS signalling pathways. However, these observations in pancreatic and lung cancer are in contrast to the results obtained in the liver, in which YAP loss failed to prevent oncogenic Kras-induced hepatocellular carcinoma41. Therefore, there are tissue-specific differences in the function of YAP during KRAS-driven tumorigenesis.

Liver kinase B1 mutations

Liver kinase B1 (LKB1; also known as STK11) was originally identified as the tumour suppressor responsible for the inherited cancer disorder Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS)46. LKB1 is also mutated in 15–35% of non-small-cell lung carcinomas and 20% of cervical carcinomas46. A small interfering RNA (siRNA) screening of the human kinome linked LKB1 to the Hippo–YAP pathway by showing that LKB1 signals through its substrates of the microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK) family to regulate the localization of protein scribble homologue (SCRIB), which can facilitate the activation of the core kinases MST and LATS47, which in turn phosphorylate and inactivate YAP (FIG. 2a). Furthermore, YAP was shown to be functionally essential for the growth of the LKB1-deficient lung adenocarcinoma line A549 and for the liver overgrowth phenotype of the Lkb1-mutant mouse47.

The tumour suppressor function of LKB1 has primarily been linked to its ability to regulate the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)–mammalian target of rapacmycin (mTOR) pathway. mTOR clearly has an important role downstream of LKB1, as mTOR inhibition by rapamycin efficiently decreases the tumour burden of existing large polyps and reduces the onset of polyposis in an Lkb1+/− mouse model of PJS46. It is noteworthy that YAP can also activate mTOR by inducing miR-29 to inhibit the translation of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), which is an upstream negative regulator of mTOR48 (FIG. 2a). This link between YAP and the LKB1 tumour suppressor pathway has substantial implications for the treatment of LKB1-mutant cancers.

Gαq and Gα11 mutations

Deep sequencing studies revealed a high rate of mutations in GPCRs and G proteins across a wide range of human cancers20. Strikingly, somatic mutations in GNAQ or GNA11 (which encode Gαq and Gα11, respectively) have been observed in more than 80% of uveal melanomas20, which is the most common intraocular tumour in adults and accounts for ~5% of all melanomas.

Recently, two independent studies have revealed that cancer-associated Gαq and Gα11 mutants activate YAP, mediating the oncogenic activity of mutant Gαq and Gα11 in uveal melanoma development49,50 (FIG. 2b). On the one hand, Yu et al.50 showed that cancer-associated Gαq and Gα11 mutants inhibit LATS, resulting in dephosphorylation and activation of YAP; on the other hand, Feng et al.49 showed that Gαq stimulated the triple functional domain protein (TRIO)–RHO and TRIO–RAC signalling to promote actin polymerization, which causes the dissociation of AMOT–YAP complexes, thereby contributing to YAP nuclear translocation independently of LATS. Although the mechanisms linking the actin cytoskeleton to YAP activation are poorly understood, both groups showed that YAP is essential in transducing the oncogenic activity of mutant Gαq and Gα11 to induce uveal melanoma. In addition, both groups successfully used the YAP and TAZ inhibitor verteporfin42 to block tumour growth of uveal melanoma cells containing Gαq and Gα11 mutations, suggesting that YAP could be a therapeutic target in these tumours.

Adenomatous polyposis coli mutations and WNT signalling

Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is the most commonly mutated tumour suppressor in human colorectal cancers and is best known as a downstream component of the WNT signalling pathway. Several studies in recent years have revealed crosstalk between the WNT and Hippo pathways30. YAP and TAZ can interact and cooperate with β-catenin in the nucleus to promote the transcriptional activation of a panel of target genes, such as SOX2, SNAI2, BCL2L1 (which encodes BCL-2-like protein 1) and BIRC5 (which encodes baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 5)25,26. Azzolin et al.23 also revealed that YAP and TAZ are transcriptionally inactivated as a result of sequestration in the β-catenin destruction complex that includes APC, whereas WNT stimulation or loss of APC causes their nuclear localization and activation of YAP–TEAD- and TAZ–TEAD-dependent transcription (FIG. 2c). The role of YAP and TAZ as mediators of WNT signalling is further evidenced by an animal model that showed that both YAP and TAZ are required for loss of APC-induced crypt hyperplasia23. Moreover, these findings are clinically relevant as YAP and TAZ have been revealed to be independent predictors of colorectal cancer progression51.

Virus-induced YAP and TAZ oncogenic activation

Some oncogenic viruses activate YAP and TAZ, mediating their oncogenic effects. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a viral GPCR that activates Gα11, Gα12, Gα13 and Gαq and thus inhibits LATS, which activates YAP and TAZ52. Similarly, viral small T oncoproteins of simian virus 40 and of Merkel cell polyomavirus activate YAP by alleviating the kinase module via NF2 inhibition53. Whether this activation of YAP and TAZ is a general feature of oncogenic viruses awaits further studies.

YAP as a tumour suppressor

Although YAP behaves as an oncogene in several cancers, recent data suggest an interesting hypothesis that YAP also has tumour suppressor functions in certain contexts.

Suppressing WNT signalling

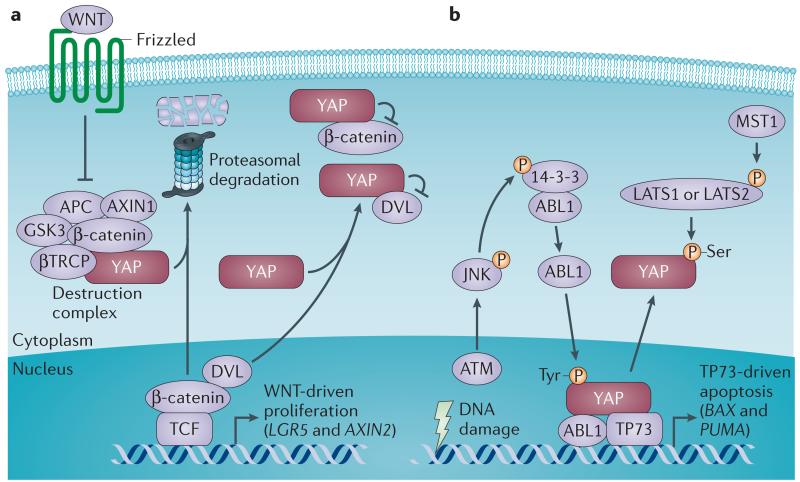

Although YAP and TAZ mediate the WNT signalling response, other studies suggest that cytoplasmic YAP and TAZ can dampen WNT signalling by multiple mechanisms30. YAP and TAZ recruit β-transducin repeat-containing protein (βTRCP) to the β-catenin destruction complex to degrade β-catenin in the absence of WNT23 (FIG. 3a). Cytoplasmic YAP and TAZ also suppress WNT signalling by sequestering β-catenin in the cytoplasm54. As Dishevelled (DVL) facilitates the WNT signalling transcriptional response when forming a complex with β-catenin–T cell factor (TCF), cytoplasmic YAP and TAZ also suppress WNT signalling by sequestering DVL in the cytoplasm24,27. Barry et al.24 found that loss of YAP can lead to WNT hypersensitivity with subsequent stem cell expansion and hyperplasia during mouse intestinal regeneration, whereas transgenic overexpression of YAP restricts WNT signals. Furthermore, YAP is silenced in a subset of highly aggressive and undifferentiated human colorectal cancers, and its re-expression can restrict the growth of colorectal carcinoma xenografts, suggesting a potential tumour suppressor role for YAP in this tissue24. Thus, a plausible scenario is one in which only cytoplasmic YAP and TAZ function as inhibitors of β-catenin, whereas nuclear YAP and TAZ function as positive mediators of WNT-associated intestinal transformation23.

Figure 3. Tumour suppressor role of YAP.

Yes-associated protein (YAP) can, in a context-dependent manner, function as a tumour suppressor by either inhibiting WNT signalling or triggering apoptosis. a | Cytoplasmic YAP dampens WNT signalling by multiple mechanisms. YAP recruits β-transducin repeat-containing protein (βTRCP) to the destruction complex for β-catenin degradation, which leads to β-catenin downregulation in the absence of WNT23. Cytoplasmic YAP also restricts the nuclear translocation of β-catenin54 and Dishevelled (DVL)24,27, which facilitates the WNT transcriptional response when forming a complex with β-catenin–T cell factor (TCF). Expression of YAP abrogates the DVL-mediated upregulation of the WNT target genes, such as LGR5 (which encodes leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5) and AXIN2 (REFS 23,24). b | Oncogene-induced DNA damage promotes the activation of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)–JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) axis to phosphorylate the adaptor protein 14-3-3 at the binding site of ABL1, releasing the ABL1 tyrosine kinase from the cytoplasm into the nucleus where it phosphorylates YAP on a tyrosine residue55. Tyrosine-phosphorylated YAP then forms a complex with the tumour suppressor TP73 to support the transcription of pro-apoptotic genes, such as BAX (which encodes BCL-2-associated X gene) and PUMA (which encodes p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis; also known as BBC3)56. Mammalian STE20-like protein kinase 1 (MST1)-induced activation of the Hippo pathway suppresses this pro-apoptotic response by phosphorylating YAP at specific serine residues and thereby inhibiting its activity56. APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; LATS, large tumour suppressor.

Triggering DNA damage-induced apoptosis

In normal haematological cells, oncogene-induced DNA damage promotes ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) activation and subsequent activation of the JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) to phosphorylate the adaptor protein 14-3-3, which releases ABL1 tyrosine kinase from the cytoplasm into the nucleus55,56 (FIG. 3b). ABL1 then phosphorylates YAP on a tyrosine residue and forms a complex with the tumour suppressor TP73 (also known as p73) to support the trans cription of pro-apoptotic genes, such as BAX (which encodes BCL-2-associated X gene) and PIG3 (also known as TP53I3)55. Cottini et al.56 identified that YAP was consistently upregulated in tumour cell lines of epithelial origin but was markedly downregulated in haematological malignancies, including lymphomas, leukaemias and multiple myeloma. Low expression of YAP prevents ABL1-induced apoptosis in the presence of DNA damage in these haematological malignancies56. Re-expression of YAP in multiple myeloma cells with YAP deletion or knockdown of MST1 in multiple myeloma cells with wild-type YAP, promoted apoptosis and growth arrest56. These results suggest that YAP has a tumour suppressor function whereas the Hippo kinase module has an oncogenic function in combination with ABL1 in the context of DNA damage in haematological malignancies. Of note, in contrast to YAP, focal deletions affecting the TAZ locus were not detected in multiple myeloma, suggesting that haematological cancers preferentially inactivate YAP56. Interestingly, a recurrent inactivating mutation encoding a G17V substitution in the GTP-binding domain of RHOA GTPase was observed in T cell lymphoma57. This mutation functions in a dominant-negative manner and thereby inhibits RHOA function57. Given the importance of RHO in YAP activation (FIG. 2), it is possible that the RHOA mutation could inactivate YAP and thus inhibit YAP–TP73-mediated apoptosis in T cell lymphoma, although this awaits formal examination.

A possible explanation for the conflicting cancer-related functions of YAP is that it can form complexes with various transcription factors that have distinct functions, which might be differentially altered in distinct types of cancers. YAP may induce the expression of pro-apoptotic genes by binding to TP73 in haematological cancers56. More speculatively, YAP and TAZ may differentially contribute to tumorigenesis by binding to various partners, depending on the cellular context. This flexibility adds an extra level of complexity to the regulation of cancer by YAP and TAZ in different tissues.

YAP and TAZ as therapeutic targets

The studies described above provide evidence for the therapeutic benefits of YAP and TAZ inhibition in cancer. The best targets for small-molecule therapeutics are generally kinases. However, efforts in this direction are frustrated by the fact that the majority of kinases in the Hippo pathway are mainly tumour suppressors, which has led to a hunt for therapeutic options beyond the core Hippo kinases.

Verteporfin

Verteporfin, which is a clinical photosensitizer in photocoagulation therapy for macular degeneration, was identified via a small-molecule library screen as a compound that inhibits the transcriptional activity of YAP42. Verteporfin abrogates the interaction between YAP and TEAD, and thus inhibits YAP-induced transcription (FIG. 2d). Importantly, in addition to the above-mentioned effects on uveal melanoma cells49,50, verteporfin also blocks YAP-induced liver tumorigenesis42, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of disrupting the YAP–TEAD and TAZ–TEAD interactions in treating cancers with aberrant YAP and TAZ hyperactivation.

VGLL4-mimicking peptide

Recent data suggest that vestigial-like family member 4 (VGLL4) is a natural inhibitor of the YAP–TEAD interaction and is capable of preventing YAP-induced cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in both D. melanogaster and mouse models58 (FIG. 2d). Jiao et al.59 identified that VGLL4 was potentially downregulated in human gastric cancer and established an association between upregulation of YAP target genes and poor prognosis of gastric cancer. On the basis of the structure of the VGLL4–TEAD4 complex, Jiao et al.59 developed a peptide-based YAP inhibitor mimicking this function of VGLL4. Treatment with this peptide suppresses tumour growth of human primary gastric cancer grown in nude mice, as well as tumorigenesis in the Helicobacter pylori-infected mouse model of gastric cancer59, providing an opportunity for treating this malignancy. As most peptide-based drugs are expensive to manufacture and inefficient to administer orally — as a result of their rapid degradation by internal enzymes — further manipulations of this peptide might be needed to extend such a therapeutic strategy.

Statins

Sorrentino et al.60 screened 640 clinically used compounds for their ability to sequester YAP and TAZ in the cytoplasm and found that statins, a class of drugs used to lower cholesterol levels in patients with hypercholesterolaemia, had the most potent effect. Statins mechanistically inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase — which is the rate-limiting enzyme of the mevalonate cholesterol biosynthesis pathway — reducing geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, which is required for membrane localization and activation of RHO GTPases. The mevalonate–RHO axis thus promotes nuclear accumulation of YAP and TAZ60,61 (FIG. 2d). Inhibition of the mevalonate pathway had antiproliferative and apoptotic effects in breast cancer cells and prevented the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie (the fly homologue of YAP and TAZ) from inducing eye overgrowth in D. melanogaster60. Also of note, substantial evidence in animal models of a wide range of cancers — including breast, colon, pancreas and liver cancers — indicates that statins have tumour suppressor effects, a conclusion that is supported by accumulating clinical studies showing a considerable negative association of statins with cancer occurrence or survival62.

Conclusions and perspectives

Given the frequent perturbation of Hippo pathway activity in human cancers, the general lack of somatic or germline mutations in core members of the pathway is still puzzling2,4. One possibility is that the pathway is fundamental during development, when constitutive activation of YAP and TAZ could be lethal. An additional plausible scenario is that mutations in components of the Hippo pathway might be identified in rare types of cancers, as the recent finding of LATS2 loss-of-function mutations in malignant mesothelioma-derived cell lines implies4. In addition, it is clear that some of the proteins that are implicated in regulation of the Hippo pathway are ‘derailed’ and mutated in cancers, such as the junctional protein E-cadherin (in breast adenocarcinomas)63, the LIM domain-containing protein AJUBA (in head and neck squamous carcinoma)63, LKB1 (REFS 46,47,64), RHOA57, and GPCRs and their cognate G proteins17,20,49,50.

YAP has very recently been shown to function not only as a proto-oncogene but also as a tumour suppressor depending on the cellular context24,56, revealing apparent cell context-dependent properties of this pathway. This dual role is not surprising given recent results that have identified new regulators and functions of the Hippo–YAP and Hippo–TAZ pathway, and have provided evidence for a model in which network-level pathway perturbations affect the activity of YAP and TAZ to contribute to tumorigenesis. Several recent proteomic studies examining the Hippo pathway interactome65 have implicated a large number of proteins and pathways that may be linked to YAP and TAZ and, thus, when further scrutinized, may contribute to our understanding of the composition and structure of this network. Delineating these interactions will have important clinical implications.

Acknowledgements

The authors apologize to their colleagues whose work could not be cited owing to space limitations and the scope of a Progress article. The authors would like to thank all the members of the Guan laboratory for insightful discussions and critical comments. The work in the Guan laboratory was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (CA132809 and EY022611) to K.-L.G. T.M. is supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad and by a grant from the Yasuda Medical Foundation. C.G.H. is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Danish Council for Independent Research | Natural Sciences.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

DATABASES

National Cancer Institute Drug Dictionary: http://www.cancer.gov/drugdictionary

Pathway Interaction Database: http://pid.nci.nih.gov

References

- 1.Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey KF, Zhang X, Thomas DM. The Hippo pathway and human cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:246–257. doi: 10.1038/nrc3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mo JS, Park HW, Guan KL. The Hippo signaling pathway in stem cell biology and cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:642–656. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson R, Halder G. The two faces of Hippo: targeting the Hippo pathway for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:63–79. doi: 10.1038/nrd4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishioka N, et al. The Hippo signaling pathway components LATS and YAP pattern TEAD4 activity to distinguish mouse trophectoderm from inner cell mass. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:398–410. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xin M, et al. Hippo pathway effector YAP promotes cardiac regeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13839–13844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313192110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varelas X. The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ and YAP in development, homeostasis and disease. Development. 2014;141:1614–1626. doi: 10.1242/dev.102376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvo F, et al. Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodelling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nature Cell Biol. 2013;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, et al. YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nature Cell Biol. 2009;11:1444–1450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii M, et al. TGFβ synergizes with defects in the Hippo pathway to stimulate human malignant mesothelioma growth. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:479–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aragona M, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dupont S, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedl P, Alexander S. Cancer invasion and the microenvironment: plasticity and reciprocity. Cell. 2011;147:992–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Y, et al. MT1-MMP-dependent control of skeletal stem cell commitment via a β1-integrin/YAP/TAZ signaling axis. Dev. Cell. 2013;25:402–416. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao B, et al. Cell detachment activates the Hippo pathway via cytoskeleton reorganization to induce anoikis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:54–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.173435.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Codelia VA, Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of YAP by mechanical strain through JNK and Hippo signaling. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:2012–2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu FX, et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao B, et al. Angiomotin is a novel Hippo pathway component that inhibits YAP oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 2011;25:51–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.2000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler JJ, et al. Serum deprivation inhibits the transcriptional co-activator YAP and cell growth via phosphorylation of the 130-kDa isoform of Angiomotin by the LATS1/2 protein kinases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17368–17373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308236110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Hayre M, et al. The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:412–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, et al. LIFR is a breast cancer metastasis suppressor upstream of the Hippo–YAP pathway and a prognostic marker. Nature Med. 2012;18:1511–1517. doi: 10.1038/nm.2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan R, Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Regulation of Hippo pathway by mitogenic growth factors via phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216462110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azzolin L, et al. YAP/TAZ incorporation in the β-Catenin destruction complex orchestrates the WNT response. Cell. 2014;158:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barry ER, et al. Restriction of intestinal stem cell expansion and the regenerative response by YAP. Nature. 2013;493:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heallen T, et al. Hippo pathway inhibits WNT signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332:458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1199010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenbluh J, et al. β-catenin-driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varelas X, et al. The Hippo pathway regulates WNT/β-catenin signaling. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varelas X, et al. TAZ controls SMAD nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and regulates human embryonic stem-cell self-renewal. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:837–848. doi: 10.1038/ncb1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alarcon C, et al. Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGFβ pathways. Cell. 2009;139:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal integration in TGFβ, WNT, and Hippo pathways. F1000Prime Rep. 2013;5:17. doi: 10.12703/P5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nature Genet. 2007;39:673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori M, et al. Hippo signaling regulates microprocessor and links cell-density-dependent miRNA biogenesis to cancer. Cell. 2014;156:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao B, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaulk SG, Lattanzi VJ, Hiemer SE, Fahlman RP, Varelas X. The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ/YAP regulate dicer expression and microRNA biogenesis through Let-7. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:1886–1891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.529362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong JH, et al. TAZ, a transcriptional modulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science. 2005;309:1074–1078. doi: 10.1126/science.1110955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordenonsi M, et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011;147:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skibinski A, et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ interacts with the SWI/SNF complex to regulate breast epithelial lineage commitment. Cell Rep. 2014;6:1059–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yimlamai D, et al. Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate. Cell. 2014;157:1324–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan SW, et al. A role for TAZ in migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2592–2598. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reginensi A, et al. YAP- and CDC42-dependent nephrogenesis and morphogenesis during mouse kidney development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang N, et al. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu-Chittenden Y, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W, et al. Downstream of mutant KRAS, the transcription regulator YAP is essential for neoplastic progression to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapoor A, et al. YAP1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2014;158:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao DD, et al. KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell. 2014;158:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ. The LKB1–AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrc2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohseni M, et al. A genetic screen identifies an LKB1–MARK signalling axis controlling the Hippo–YAP pathway. Nature Cell Biol. 2014;16:108–117. doi: 10.1038/ncb2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tumaneng K, et al. YAP mediates crosstalk between the Hippo and PI(3)K–TOR pathways by suppressing PTEN via miR-29. Nature Cell Biol. 2012;14:1322–1329. doi: 10.1038/ncb2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng X, et al. Hippo-independent activation of YAP by the GNAQ uveal melanoma oncogene through a trio-regulated rho GTPase signaling circuitry. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:831–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu FX, et al. Mutant Gq/11 promote uveal melanoma tumorigenesis by activating YAP. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, et al. Overexpression of YAP and TAZ is an independent predictor of prognosis in colorectal cancer and related to the proliferation and metastasis of colon cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Liu G, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus promotes tumorigenesis by modulating the Hippo pathway. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2014.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen HT, et al. Viral small T oncoproteins transform cells by alleviating Hippo-pathway-mediated inhibition of the YAP proto-oncogene. Cell Rep. 2014;8:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imajo M, Miyatake K, Iimura A, Miyamoto A, Nishida E. A molecular mechanism that links Hippo signalling to the inhibition of WNT/β-catenin signalling. EMBO J. 2012;31:1109–1122. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. YAP1 phosphorylation by c-ABL is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:350–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cottini F, et al. Rescue of Hippo coactivator YAP1 triggers DNA damage-induced apoptosis in hematological cancers. Nature Med. 2014;20:599–606. doi: 10.1038/nm.3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoo HY, et al. A recurrent inactivating mutation in RHOA GTPase in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Nature Genet. 2014;46:371–375. doi: 10.1038/ng.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koontz LM, et al. The Hippo effector Yorkie controls normal tissue growth by antagonizing scalloped-mediated default repression. Dev. Cell. 2013;25:388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiao S, et al. A peptide mimicking VGLL4 function acts as a YAP antagonist therapy against gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:166–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sorrentino G, et al. Metabolic control of YAP and TAZ by the mevalonate pathway. Nature Cell Biol. 2014;16:357–366. doi: 10.1038/ncb2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Z, et al. Interplay of mevalonate and Hippo pathways regulates RHAMM transcription via YAP to modulate breast cancer cell motility. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E89–E98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319190110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gronich N, Rennert G. Beyond aspirin-cancer prevention with statins, metformin and bisphosphonates. Nature Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013;10:625–642. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kandoth C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nguyen HB, Babcock JT, Wells CD, Quilliam LA. LKB1 tumor suppressor regulates AMP kinase/mTOR-independent cell growth and proliferation via the phosphorylation of YAP. Oncogene. 2013;32:4100–4109. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moya IM, Halder G. Discovering the Hippo pathway protein–protein interactome. Cell Res. 2014;24:137–138. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]