Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Neuropathologic assessment is the current “gold standard” for evaluating the Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but there is no consensus on methods used.

METHODS

Fifteen unstained slides (eight brain regions) from each of the fourteen cases were prepared and distributed to ten different National Institute on Aging AD Centers for application of usual staining and evaluation following recently revised guidelines for AD neuropathologic change.

RESULTS

Current practice used in the AD Centers program achieved robustly excellent agreement for the severity score for AD neuropathologic change (average weighted κ =.88, 95% CI: 0.77 – 0.95), and good to excellent agreement for the three supporting scores. Some improvement was observed with consensus evaluation but not with central staining of slides. Evaluation of glass slides and digitally-prepared whole slide images was comparable.

CONCLUSION

AD neuropathologic evaluation as performed across AD Centers yields data that have high agreement with potential modifications for modest improvements.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neuropathology, methods, whole slide imaging, multisite

1. INTRODUCTION

The National Institute on Aging (NIA) in collaboration with the Alzheimer’s Association (AA) recently convened a group of expert neuropathologists to revise the 1997 consensus guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to reflect advances in knowledge over the intervening fifteen years. The product of that committee’s work is now published as the NIA-AA guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of AD and related illnesses that commonly contribute to cognitive impairment and dementia in the elderly [1, 2].

As part of fulfilling this charge, the committee recognized there was no consensus on optimal methods for tissue staining and evaluation of AD neuropathologic change, and so made recommendations on preferred approaches. Although an improvement, this lack of consensus remains a potentially serious limitation to the field of AD research because variation in staining methods or idiosyncrasies in evaluation could lead to varying limits of detection and scoring of neuropathologic changes. Substantial variation in approach potentially could undermine the use of neuropathologic evaluation as the “gold standard” in correlation with other data such as genomics, molecular neuroimaging, biomarkers, and cognitive and behavioral testing. The goal of this study is to begin to fill this gap in our knowledge by undertaking a collaborative study of different methods for neuropathologic assessment among ten AD Centers.

We sought to determine the degree of variation in the neuropathologic assessment of AD using different combinations of staining protocols and evaluators. First, we determined the degree of observed variance in current practice, which is characterized by independent evaluators with independent staining protocols. Next, we attempted to focus on particular potential sources of variance, by varying either the evaluator or the staining protocol. Finally, we determined the variance of neuropathologic evaluation of whole slide images (WSI) in anticipation of increasing future use of digital pathology.

2. METHODS

Our study was a collaborative effort among ten AD Centers. Neuropathologists at the different sites worked completely independently of each other, were blinded to the level of neuropathologic change for each case, and were not aware of determinations made by other neuropathologists. Each site had one neuropathologist performing evaluations with the exception of the University of Pennsylvania where Dr. E.B. Lee and Dr. J.Q. Trojanowski worked together. Dr. Frosch and Dr. Sonnen were the sole evaluators at their institutions without any input from other institutional colleagues involved in this project. Central evaluations were performed by six neuropathologists at a multi-headed microscope (Drs. Bigio, Frosch, Hyman, Montine, Nelson, and Schneider) and evaluated a representative set of slides, with adjudication by Drs. Hyman and Montine.

Cases and their evaluation

All evaluations followed the NIA-AA guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of AD that specify an “ABC” score and from it assign a severity level of AD neuropathologic change [1, 2]. The “ABC” score derives from modified versions of the original protocols for Thal Phases of Aβ deposition (“A”) [3], Braak staging for neurofibrillary degeneration (“B”) [4], and CERAD neuritic plaque score (“C”) [5] that all have been converted into four-point scales that span 0 to 3. The severity level of AD neuropathologic change is a synthesis of these three dimensions into a single descriptor: not AD, low, intermediate, or high AD neuropathologic change. The fourteen cases selected from the University of Washington (UW) had varying severity levels of AD neuropathologic change, and did not have evidence of Lewy body disease, vascular brain injury, hippocampal sclerosis, or TDP-43 inclusions: two with not AD, four with low, four with intermediate level, and four with high level of AD neuropathologic change as assessed initially [1, 2].

Fifteen unstained slides (eight brain regions) from each of the fourteen cases (210 total unstained slides) were prepared and distributed to each site for usual staining and evaluation of AD neuropathologic change following the recently revised guidelines [1, 2] (Table 1 and Table S1). Each site performed their usual histochemical and immunohistochemical stains on the unstained slides, and then returned all stained slides and scoring sheets to UW. Importantly, all staining methods used by the different sites were “preferred” or “acceptable alternatives” by NIA-AA guidelines [1, 2].

Table 1. Brain regions and stains.

| For “A” score^ | For “B” score# | For “C” score* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ Stain | NFT Stain | NP Stain | |

| Middle frontal gyrus | X | X | X |

| Superior and middle temporal gyri | X | X | X |

| Inferior parietal lobule | X | X | X |

| Occipital Cortex (BA 17 & 18) | X | ||

| Hippocampus and entorhinal cortex | X | X | |

| Basal ganglia at anterior commissure | X | ||

| Midbrain including substantia nigra | X | ||

| Cerebellar cortex | X |

Staining methods used by different sites included:

immunohistochemistry for Aβ (antibodies (source) 6E10 (Covance), 6F/3D (DAKO), 4G8 (Covance), NAB228 (University of Pennsylvania), 10D5 (Elan), and AB5074P and AB5078P (Chemicon);

immunohistochemistry for neurofibrillary degeneration (antibodies PHF-1 (Dr. Peter Davies), Tau (DAKO), AT8 (Autogen Bioclear), MN1020 (Thermo Scientific), and

histochemistry (Thioflavin S or Bielschowsky stain) or immunohistochemistry (NM1020 or PHF-1) for neuritic plaques. Staining methods used by site are shown in Table S1.

Eight cases with AD neuropathologic change varying from not AD to high were selected from those stained locally. All slides were re-labeled and used as a representative set of stained slides. The representative set was distributed to the sites, one at a time, for evaluation by each of the ten neuropathologists. Consensus evaluation was performed during a one-day session on five of the cases in the representative set. Finally, slides from the eight cases in the representative set were scanned and stored at 40x resolution with an Aperio ScanScope CS system at UW, and WSI evaluated by the 10 neuropathologists at participating sites.

Statistical analysis

Agreement across raters was assessed using Cohen’s weighted κ statistic [6], an extension of the original Cohen’s κ [7]. Like the original κ, the weighted κ measures agreement above chance; however, it also allows for the evaluation of ordinal measures, not just binary outcomes. In all analyses, squared distance weights were used so that discordant ratings were penalized by their distance from each other. For example, if one neuropathologist gave a rating of not AD and the other gave a rating of intermediate AD neuropathologic change, the resulting weighted κ statistic would be lower than if the two ratings were not AD and low AD neuropathologic change.

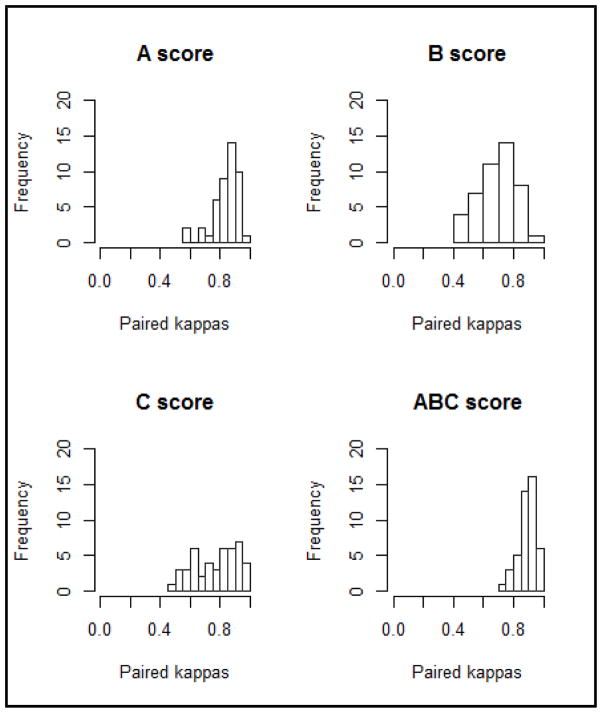

For each of the measures of interest (A score, B score, C score, and severity score for AD neuropathologic change), a weighted κ was calculated for every possible pair of evaluators’ ratings, resulting in 45 paired ratings for each measure. These 45 weighted κ statistics were then plotted in a histogram in order to evaluate the variation and potential patterns of agreement between any two evaluators. The range and average of all the paired ratings were calculated for each specific aim. All of the cases analyzed fell into a category; there was no missing data nor unknown responses.

Cutoffs were applied to the average of the weighted κ in order to facilitate interpretation. As there are no recommended cutoffs for the average of the weighted κ, we applied the cutoffs for the standard κ statistic. In general, a κ statistic of 1 indicates perfect agreement, while 0 indicates agreement equivalent to that expected by chance. In general, κ >0.75 is considered “excellent” agreement, 0.4–0 – 0.75 is “good” agreement, and <0.4 is “poor” agreement. Next, the jackknife method [8] was used to explore influential cases and evaluators. We calculated the average weighted κ for each score in each aim removing one case at a time. We then repeated this process removing one evaluator at a time. Substantial changes in the average weighted κ statistic would suggest that one case or one evaluator was inflating or deflating the results more than the others. We then used the bootstrap method [8] to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the average of the weighted κ statistics. Since the correlation structure of these data is complicated, we resampled only the cases, not the evaluators. Thus, the CIs reflect only the neuropathologists in this study. For all parameters, 1000 bootstrap samples were produced and then ordered to obtain 95% CIs.

All analyses were run using R version 3.1.1. Package ‘irr’ was used to calculate the weighted κ statistics [9].

3. RESULTS

Results for current practice, meaning slides stained and evaluated at ten independent sites, are summarized in Table 2. Of the 14 cases assessed, the 10 neuropathologists were in complete agreement for 4 cases in assessing the ABC score; of the remaining 10 cases, 3 had 9 of 10, 2 had 8 of 10, 3 had 7 of 10, and 2 had 6 of 10 in agreement. The distribution of paired κ statistics for severity, A, B, and C scores are presented in Figure 1. Of the 560 scores provided by the ten evaluators, four severity scores were miscoded according to the Thal phasing, Braak staging, or CERAD scoring noted by the neuropathologist; these were left uncorrected in the analysis. Table 2 shows that the 95% CI for average weighted κ was excellent (k=.88, 95% CI: 0.77 – 0.95) for severity score, and ranged from good to excellent for A, B, and C scores for the fourteen cases stained locally and evaluated independently.

Table 2. Current practice.

Agreement for independent evaluation of locally-stained slides (14 cases and 10 neuropathologists).

| Average weighted κ | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Severity score | 0.88 | (0.77–0.95) |

| A score | 0.84 | (0.68–0.92) |

| B score | 0.70 | (0.45–0.83) |

| C score | 0.77 | (0.58–0.88) |

Figure 1.

Histogram of paired κ for current practice (independent evaluation of locally-stained slides).

We sought the major contributors to variance in current practice by first focusing on variation due to interpretation by the individual neuropathologists. In order to eliminate variation due to the slides themselves, we assembled a representative set of stained slides that were circulated around the US for independent evaluation by the ten neuropathologists (Table 3 and Supplemental Figure 1). Independent evaluation of slides in the representative set yielded average weighted κ that was 17% or 18% lower than current practice (independent evaluation of locally-stained slides) for severity score, A score, and B score but with only −2% change in average weighted κ for C score. For A and B scores, there was no clear tendency of over vs. under assessment; scores were either mixed or had a few deviations in both directions. There was, however, more variation in reported scores when low or intermediate pathologic change was present compared to when severe pathologic change was present. Independent evaluation of slides in the representative slide set shifted 95% CI to include the poor range, while current practice had 95% CI for all four scores ranging from good to excellent. Thus, these results suggest that central staining followed by distributed evaluation may actually lower average agreement across evaluators, perhaps indicating that a given neuropathologist is most adept at interpretation of the product of his or her laboratory. Still, it is important to note that while the average weighted kappa estimates were different, the 95% CI for these two approaches (independent evaluation of slides in the representative slide set and independent evaluation of locally-stained slides) overlapped for the severity, A, B, and C, scores.

Table 3. Estimate of variation from Evaluator.

Agreement for independent evaluation of a representative set of stained slides (8 cases) among the 10 neuropathologists. For direct comparison is agreement for the same 8 cases using locally-stained slides among the same 10 neuropathologists.

| Representative set of slides | Locally-stained slides | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Average weighted κ | 95% CI | Average weighted κ | 95% CI | |

| Severity score | 0.70 | (0.31–0.84) | 0.84 | (0.56–0.91) |

| A score | 0.67 | (0.33–0.84) | 0.81 | (0.50–0.90) |

| B score | 0.68 | (0.37–0.81) | 0.83 | (0.61–0.92) |

| C score | 0.71 | (0.42–0.88) | 0.73 | (0.52–0.83) |

Next, we focused on variance in scores resulting from staining protocol (Table 4 and Supplemental Figure 2). Stained slides from six different sites for five cases in the representative set that had varying AD neuropathologic change were assembled for consensus evaluation. Thus, the staining protocol varied but the evaluation was always by consensus. For direct comparison, average weighted κ for independent evaluation of the same five cases, among the six neuropathologists whose slides were selected for the consensus evaluation, was calculated. The 95% CI for both conditions for evaluating these five cases ranged from poor to excellent. Consensus evaluation increased average weighted κ by 20 to 25% for severity score, A score, and B score but only 4% change for C score. These results indicate that consensus evaluation improves agreement when compared directly to independent evaluation of the same cases; however, as in the previous comparison, the 95% CI overlapped, requiring cautious interpretation of the observed differences.

Table 4. Estimate of variation from staining protocol.

Agreement among consensus evaluation (6 sets of slides stained at different sites for 5 cases). For direct comparison is agreement among independent evaluation for the same 5 cases by the 6 neuropathologists whose slides were included in consensus evaluation.

| Consensus evaluation | Independent evaluation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Average weighted κ | 95% CI | Average weighted κ | 95% CI | |

| Severity score | 0.84 | (0.48–0.96) | 0.67 | (0.33–0.80) |

| A score | 0.80 | (0.67–0.87) | 0.64 | (0.29–0.80) |

| B score | 0.90 | (0.43–1.00) | 0.75 | (0.49–0.90) |

| C score | 0.51 | (0.26–0.79) | 0.49 | (0.16–0.70) |

Finally, we assessed the influence of WSI on variance in scoring cases. WSI of the representative set of stained slides were recoded again, posted online, and underwent independent evaluation by neuropathologists at the ten sites (Table 5 and Supplemental Figure 3). Independent evaluation of WSI improved B score (4%) and C score (14%) but diminished severity score (−10%) and A score (−19%).

Table 5. Estimate of variation with whole slide imaging.

Agreement for independent evaluation of WSI using the representative slide set (10 neuropathologists). For direct comparison is agreement for current practice of the same 8 cases and 10 neuropathologists.

| Whole slide imaging | Glass slides | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Average weighted κ | 95% CI | Average weighted κ | 95% CI | |

| Severity score | 0.76 | (0.45–0.86) | 0.84 | (0.56–0.91) |

| A score | 0.66 | (0.37–0.81) | 0.81 | (0.50–0.90) |

| B score | 0.86 | (0.65–0.92) | 0.83 | (0.61–0.92) |

| C score | 0.83 | (0.56–0.93) | 0.73 | (0.52–0.83) |

4. DISCUSSION

The goal of our study was to determine the extent, sources, and potential approaches to mitigate variation in the neuropathologic assessment of AD. We are aware of no other effort to obtain these data within the AD Centers Program. Our results showed that the current practice of neuropathologic evaluation of AD used in the AD Centers program, i.e., local staining and independent evaluation, achieved robustly excellent agreement for the severity score for AD neuropathologic change (average weighted κ=.88, 95% CI: 0.77 – 0.95). Agreement for A, B, and C scores had average weighted κ statistics that were good or excellent, and 95% CI that spanned from good to excellent values. Overall, these results show that the process by which AD neuropathologic evaluation is performed across AD Centers yields data that have high agreement. This is an important point because it underscores the comparability of these neuropathologic data across AD Centers that have been assembled by the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center and already used in over 45 publications.

Colleagues in Europe have attempted a related study through the BrainNet Europe Consortium. However, the design and goals of the BrainNet study are markedly different from ours. BrainNet used blocks of only temporal lobe from 21 AD cases to create a tissue microarray that was then stained and pathologic lesions scored at 17 participating centers [10–12]; noteworthy, BrainNet used original scoring protocols and not NIA-AA guidelines, complicating a direct comparison of results. BrainNet has determined that immunohistochemical approaches are superior to histochemical approaches for some lesions, and these findings were incorporated already into the NIA-AA revised guidelines [1, 2]. However, BrainNet was not designed to determine the major sources of variation in neuropathologic assessment of AD. Indeed, BrainNet assessed agreement using absolute percentages and the Kruskal-Wallis test, which tests whether or not the samples are likely to have come from the same distribution. This approach does not compare each sample across individual raters, but rather compares the overall distribution of all the evaluations for each rater. In our analysis, we used the κ statistic, which evaluates inter-rater agreement while accounting for agreement occurring by chance. Therefore, because of BrainNet’s designed purpose to focus on temporal lobe and their statistical approach, its data cannot be used to sort out the major sources of variation in the neuropathologic assessment of AD.

We explored potential means to improve on the already good to excellent practice standard either by central staining of slides or consensus evaluation. Independent evaluation of slides stained at different sites lowered agreement of three of the four scores, so a central staining facility does not seem to be an effective means to increase agreement. In contrast, consensus evaluation increased agreement across individually stained slides for severity score, A score, and B score, while C score was relatively unchanged. This suggests that one mechanism to decrease variance in the neuropathologic assessment of AD would be to implement consensus training or perhaps digitally link neuropathologists across different sites for consultation and consensus of locally-stained slides. Interestingly, although it tended to have the lowest agreement, perhaps due to greater variation among staining methods, the C score was more consistent across evaluation scenarios than A and B scores. There are several possible reasons for this outcome including that the CERAD neuritic plaque scoring guidelines may provide clearer separation of categories.

Our last investigation sought to determine the potential change in variance introduced by WSI. It is important to recognize that our group has variable, and overall limited, experience with assessment of WSI compared to extensive experience with glass slides and light microscopy. While one might expect that less technical familiarity may increase variance, others have observed the opposite in surgical neuropathology [13, 14], and prior studies of AD neuropathologic change indicate that digital methods can provide insights beyond the limitations of human observation [15]. Our results were mixed with reduced variance in some scores and increased variance in others with WSI compared to glass slides and microscopy. Even with limited experience, overall WSI achieved variance in histopathologic scoring for AD neuropathologic change that was similar to the standard approach of glass slides and light microscopy.

In summary, we find that current AD research site practice yields good to excellent comparisons across sites and investigators. Improvements might come with consensus training, and potentially with WSI. Overall, our study supports continued use of current diagnostic criteria and utilization of multisite data acquisition to evaluate clinco-pathologic and genotype correlations in a research setting.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Histogram of paired weighted κ statistics for independent evaluation of central set of stained slides (8 cases) among the 10 neuropathologists.

Supplemental Figure 2: Histogram of paired weighted κ statistics for consensus evaluation (6 sets of slides stained at different sites for 5 cases).

Supplemental Figure 3: Histogram of paired weighted κ statistics for independent evaluation of WSI using the central slide set (10 neuropathologists).

6E10 (Covance), 6F/3D (DAKO), 4G8 (Covance), NAB228 (University of Pennsylvania), 10D5 (Elan), AB5074P and AB5078P (Chemicon), PHF-1 (Dr. Peter Davies), Tau (DAKO), AT8 (Autogen Bioclear), and MN1020 (Thermo Scientific)

RESEARCH in CONTEXT.

The goal of our study was to determine the extent, sources, and potential approaches to mitigate variation in the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). We are aware of no other effort to obtain these data within the NIA AD Centers Program. Our results showed that the current practice of neuropathologic evaluation used in the AD Centers program, i.e., local staining and independent evaluation, achieved robustly excellent agreement for the severity score for AD neuropathologic change (average weighted κ=.88, 95% CI: 0.77 – 0.95). Agreement for subscores for amyloid β, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuritic plaques had average weighted κ statistics that were good or excellent. Central evaluation yielded modest improvements. Evaluation of digital whole slide images was comparable to glass slides. These results show that the process by which AD neuropathologic evaluation is performed across AD Centers yields data that have high agreement with potential areas for modest improvement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD: the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (U01 AG016976), Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (P50 AG05133, P50 AG05134, P50 AG05136, P50 AG05681, P30 AG10161, P30 AG10124, P30 AG13854, P50 AG16570, P30 AG19610, P30 AG28383), and P01 AG03991. We thank Dr. Kathleen Montine for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References cited

- 1.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Thies B, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Montine TJ. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Hyman BT. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968;70:213–20. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Efron B. The Jackknife, the Bootstrap, and Other Resampling Plans. CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamer M, Lemon J, Fellows I, Singh P. irr: Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. R package version 0.84. Package ‘irr’. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alafuzoff I, Pikkarainen M, Arzberger T, Thal DR, Al-Sarraj S, Bell J, Bodi I, Budka H, Capetillo-Zarate E, Ferrer I, Gelpi E, Gentleman S, Giaccone G, Kavantzas N, King A, Korkolopoulou P, Kovacs GG, Meyronet D, Monoranu C, Parchi P, Patsouris E, Roggendorf W, Stadelmann C, Streichenberger N, Tagliavini F, Kretzschmar H. Inter-laboratory comparison of neuropathological assessments of beta-amyloid protein: a study of the BrainNet Europe consortium. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:533–46. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alafuzoff I, Pikkarainen M, Al-Sarraj S, Arzberger T, Bell J, Bodi I, Bogdanovic N, Budka H, Bugiani O, Ferrer I, Gelpi E, Giaccone G, Graeber MB, Hauw JJ, Kamphorst W, King A, Kopp N, Korkolopoulou P, Kovacs GG, Meyronet D, Parchi P, Patsouris E, Preusser M, Ravid R, Roggendorf W, Seilhean D, Streichenberger N, Thal DR, Kretzschmar H. Interlaboratory comparison of assessments of Alzheimer disease-related lesions: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:740–57. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229986.17548.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horbinski C, Wiley CA. Comparison of telepathology systems in neuropathological intraoperative consultations. Neuropathology. 2009;29:655–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiley CA, Murdoch G, Parwani A, Cudahy T, Wilson D, Payner T, Springer K, Lewis T. Interinstitutional and interstate teleneuropathology. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:21. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.80717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neltner JH, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Denison SK, Anderson S, Patel E, Nelson PT. Digital pathology and image analysis for robust high-throughput quantitative assessment of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:1075–85. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182768de4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Histogram of paired weighted κ statistics for independent evaluation of central set of stained slides (8 cases) among the 10 neuropathologists.

Supplemental Figure 2: Histogram of paired weighted κ statistics for consensus evaluation (6 sets of slides stained at different sites for 5 cases).

Supplemental Figure 3: Histogram of paired weighted κ statistics for independent evaluation of WSI using the central slide set (10 neuropathologists).

6E10 (Covance), 6F/3D (DAKO), 4G8 (Covance), NAB228 (University of Pennsylvania), 10D5 (Elan), AB5074P and AB5078P (Chemicon), PHF-1 (Dr. Peter Davies), Tau (DAKO), AT8 (Autogen Bioclear), and MN1020 (Thermo Scientific)