Abstract

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) is a relatively recently identified non-nuclear estrogen receptor, expressed in several tissues, including brain and blood vessels. The mechanisms elicited by GPER activation in brain microvascular endothelial cells are incompletely understood. The purpose of this work was to assess the effects of GPER activation on cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]i, nitric oxide (NO) production, membrane potential and cell nanomechanics in rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVEC). Extracellular but not intracellular administration of G-1, a selective GPER agonist, or extracellular administration of 17-β-estradiol and tamoxifen, increased [Ca2+]i in RBMVEC. The effect of G-1 on [Ca2+]i was abolished in Ca2+-free saline or in the presence of a L-type Ca2+ channel blocker. G-1 increased NO production in RBMVEC; the effect was prevented by NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME). G-1 elicited membrane hyperpolarization that was abolished by the antagonists of small and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, apamin and charibdotoxin. GPER-mediated responses were sensitive to G-36, a GPER antagonist. In addition, atomic force microscopy studies revealed that G-1 increased the modulus of elasticity, indicative of cytoskeletal changes and increase in RBMVEC stiffness. Our results unravel the mechanisms underlying GPER-mediated effects in RBMVEC with implications for the effect of estrogen on cerebral microvasculature.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, blood-brain barrier, calcium signaling, cerebral microvasculature, GPER

Introduction

Estrogen exerts its effects by interacting with classical nuclear receptors and via the G protein-coupled receptor (GPER), previously named GPR30 (Prossnitz and Barton, 2014; Alexander et al., 2013). GPER is expressed in several tissues, including the brain and blood vessels (Owman et al., 1996; Brailoiu et al., 2007; Prossnitz et al., 2008). In the vascular system, GPER was identified in endothelial and smooth muscle cells of human and rodent arteries and veins (Takada et al., 1997, Haas et al., 2007, Isensee et al., 2009, Broughton et al., 2010). Studies in transgenic mouse line Gpr30-lacZ indicated that the brain blood vessels expressed the receptor (Isensee et al., 2009).

Increasing evidence supports the contribution of the GPER in rapid vascular responses (Lindsey & Chappell, 2011; Lindsey et al., 2014). Activation of GPER causes vasodilation in isolated arteries from rodents and humans, reduces blood pressure in vivo, and inhibits human vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation (Haas et al., 2009, Broughton et al., 2010, Meyer et al., 2010).

GPER activation elicited endothelium-dependent vasodilation in rat carotid arteries (Broughton et al., 2010), while in rat mesenteric arteries (Lindsey et al., 2014) and epicardial coronary arteries (Meyer et al., 2010) both endothelium-dependent and -independent mechanisms were involved in GPER-mediated vasodilation. Recently, G-1, the GPER agonist (Bologa et al., 2006), was reported to produce vasodilation in cerebral microvascular arterioles by acting on both endothelium and vascular smooth muscle (Murata et al., 2013).

The mechanisms employed by GPER in brain endothelial cells are incompletely characterized. We examined the effects of GPER activation and the cellular mechanisms involved in rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVEC), an essential component of the blood-brain-barrier.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

GPER ligands, G-1 and G-36, were from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). H-89, PKA inhibitor, was from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA). Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise mentioned.

Cell Culture

Rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVEC) from Cell Applications, Inc (San Diego, CA) were cultured in rat brain endothelial basal medium and rat brain endothelial growth supplement, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cell Applications, Inc). Cells were grown in T75 flasks coated with attachment factor (Cell Applications, Inc) until 80% confluent. Cells were plated on round coverslips of 12 mm (for AFM studies) or 25 mm diameter (the rest of the studies), coated with human fibronectin (Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA).

Western Blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were separated on Mini-PROTEAN TGX 4–20% gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Proteins were transferred to an Odyssey nitrocellulose membrane (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska). After blocking with Odyssey blocking buffer, the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibody against GPER (rabbit polyclonal against GPER, C-term, 1:200, Abgent, Inc, San Diego, CA). An antibody against β-actin (mouse monoclonal, 1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to confirm equal protein loading. Membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with the secondary antibodies: IRDye 800CW conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, and IRDye 680 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, 1 h at room temperature). Membranes were then washed in TBST and scanned using a Li-Cor Odyssey Infrared Imager and analyzed using Odyssey V.3 software.

Cytosolic Ca2+ measurement

Measurements of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]i, were performed as previously described (Brailoiu et al., 2013a,b, 2014). Briefly, cells were incubated with 5 μM Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) at room temperature for one hour and washed with dye-free HBSS. Coverslips were mounted in an open bath chamber (QR-40LP, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) on the stage of an inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse TiE (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY), equipped with a Perfect Focus System and a Photometrics CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Fura-2 AM fluorescence (emission 510 nm), following alternate excitation at 340 and 380 nm, was acquired at a frequency of 0.25 Hz. Images were acquired/analyzed using NIS-Elements AR 4.13 software (Nikon, Inc.). The ratio of the fluorescence signals (340/380 nm) was converted to Ca2+ concentrations (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985).

Intracellular microinjection

Intracellular microinjections were performed using FemtotipsII, InjectManNI2 and FemtoJet systems (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) as previously reported (Brailoiu et al., 2011). Pipettes were back-filled with an intracellular solution containing, in mM: 110 KCl, 10 NaCl and 20 HEPES (pH 7.2) or the compounds to be tested (G-1 and inositol 1,4,5-trisphophate). The injection time was 0.4 s at 60 hPa with a compensation pressure of 20 hPa in order to maintain the microinjected volume to less than 1% of cell volume, as measured by microinjection of a fluorescent compound (Fura-2 free acid). The intracellular concentration of chemicals was determined based on the concentration in the pipette and the volume of injection.

NO measurement

Intracellular NO was monitored with DAF-FM [(4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluoro-fluorescein) diacetate] (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), a pH-insensitive fluorescent dye that emits increased fluorescence upon reaction with an active intermediate of NO formed during spontaneous oxidation of NO to NO2− (Kojima et al., 1998). RBMVEC were incubated at room temperature for 45 min in HBSS containing 0.5 μM of DAF-FM diacetate, as previously reported (Brailoiu et al., 2010). DAF-FM fluorescence (excitation/emission – 480 nm/540 nm) was acquired at a frequency of 0.1 Hz.

Measurement of membrane potential

The relative changes of RBMVEC membrane potential were evaluated using bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)-trimethine-oxonol, DiBAC4(3), a voltage-sensitive dye, as reported (Brauner et al., 1984; Brailoiu et al. 2013b, 2014). RBMVEC were incubated for 30 min in HBSS containing 0.5 μM DiBAC4(3) and the fluorescence (excitation/emission - 480nm/540nm) was monitored at 0.1 Hz. Upon membrane hyperpolarization, the dye concentrates in the cell membrane leading to a decrease of fluorescence intensity, whereas depolarization results in a sequestration of the dye into cytosol and is associated with an increase in the fluorescence intensity (Brauner et al., 1984).

Drug treatment

In calcium imaging, NO and membrane potential measurement experiments, drugs were applied by perfusion using a MiniPuls 3 peristaltic pump (Gilson Inc., Middleton, WI) at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The antagonists (G-36, apamin, charibdotoxin) were applied in preincubation for 20 min and for the duration of G-1 application.

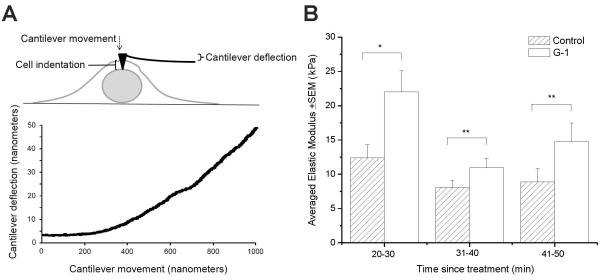

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

We used atomic force microscopy (AFM), a nanotechnique that reliably measures stiffness and deformability in endothelial cells (Oberleithner et al., 2007) to assess the effect of GPER activation on RBMVEC elasticity aspreviously reported (Mathur et al., 2001). AFM allows cells to be indented with small probes attached to cantilevers with low spring constants (Arce et al., 2008). The cell and cantilever displacements were recorded and used, along with the spring constant, to calculate the force that the cell exerts on the cantilever as the cell was indented. Each indentation generated a force curve which was analyzed to determine the modulus of elasticity, as. RBMVEC cultured on 12 mm diameter coverslips were fastened to a metal disk using epoxy. Cells were either exposed to vehicle or to G-1 (10 μM) for a period of five minutes. After allowing the epoxy to cure for eight minutes, the metal disk was transferred to the MultiMode V AFM (Bruker Corporation, Goleta, CA). The cells were imaged in a fluid cell containing HBSS. DNP cantilevers with a spring constant of 0.06 N/m (Bruker Corporation) were used in contact mode to locate the center of the nucleus. Force curves were generated by indenting the cell membrane with the probe andanalyzed using NanoScope Analysis 1.4 using the Sneddon fit model. Data from each group (control and G-1 treated) were compared at 20-30 minutes, 31-40 minutes, and 41-50 minutes post exposure.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Mann-Whitney U test (for AFM studies) or one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis using Bonferonni and Tukey tests (for the rest of the studies) were used to evaluate significant differences between groups; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

GPER is expressed in RBMVEC

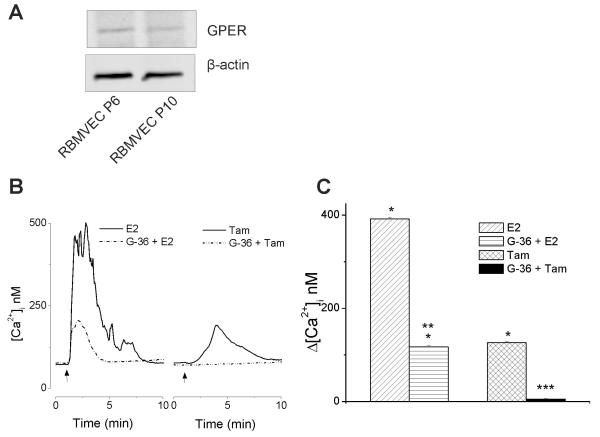

Western blot analysis of the whole-cell lysate identified GPER protein expression, as a band around 37-40 kDa, in both early and later passages of RBMVEC (Fig.1A).

Fig. 1. GPER activation increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in RBMVEC.

A, Rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVEC) express GPER. Western blot analysis of RBMVEC passage 6 (P6) and 10 (P10) indicating the presence of GPER at the protein level; β-actin was used as an internal loading control. Results are representative of three independent experiments. B, Representative traces showing increases in [Ca2+]i produced by activation of GPER by 17β-estradiol (E2, 100 nM) and tamoxifen (Tam, 10 μM). G-36, the GPER antagonist, reduced the response to E2 and abolished the response to tamoxifen. C, Comparison of the amplitude of increase in [Ca2+]i elicited by E2, and tamoxifen in the absence and presence of G-36. P < 0.05 as compared to basal [Ca2+]i (*), to the [Ca2+]i increase produced by E2 (**), or by tamoxifen (***)

GPER activation increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in RBMVEC

Treatment of RBMVEC with 17β-estradiol (E2) (100 nM) produced a fast and sustained increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]i,, by 392 ± 3.9 nM (n = 18); a representative trace is shown in Fig. 1B; pretreatment with the GPER antagonist, G-36 (10 μM) reduced the response to E2 (Δ[Ca2+]i = 117 ± 2.6 nM (n = 32). Tamoxifen (10 μM), a selective estrogen receptor modulator and GPER agonist (Thomas et al., 2005), produced a modest and transitory increase in [Ca2+]i by 126 ± 2.4 nM (n = 28) (Fig. 1B). The tamoxifen-induced increase in [Ca2+]i was abolished by pretreatment with G-36 (10 μM); Δ[Ca2+]i = 5 ± 1.3 nM. Comparison of the amplitude of the increase in [Ca2+]i elicited by E2, and tamoxifen in the absence and presence of G-36 is shown in Fig. 1C

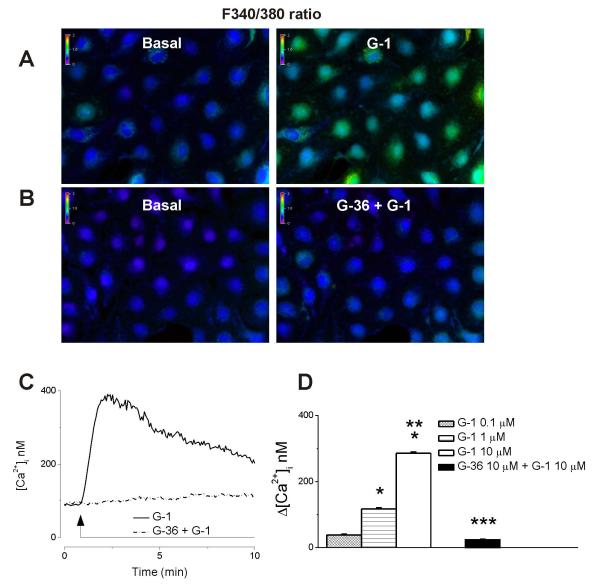

Treatment of RBMVEC with G-1 (10 μM), a GPER selective agonist that does not bind ERα and ERβ (Bologa et al., 2006), produced a sustained increase in Fura-2 AM 340/380 fluorescence ratio that was prevented by the GPER antagonist, G-36 (10 μM). (Fig 2A, B). G-1 (10 μM) produced a robust and long-lasting increase in [Ca2+]i; a representative trace is shown in Fig. 2C (solid trace); the effect was abolished by G-36 (Fig. 2C, dotted trace).

Fig. 2. G-1 produced a dose-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i via GPER activation.

AB, Changes in Fura 2-AM fluorescence ratio (340/380 nm) produced by the GPER agonist, G-1 (10 μM) in the absence and presence of the GPER antagonist, G-36 (10 μM). C, Representative example of sustained increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i produced by G-1 (solid trace); the response was abolished by G-36 (dotted trace). D, G-1 (0.1 μM, 1 μM and 10 μM) produced a dose-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i.. P < 0.05 as compared to basal [Ca2+]i,(*), the [Ca2+]i increase produced by G-1 (1 μM) (**), or by G-1 (10 μM) (***).

G-1 (0.1 μM, 1 μM and 10 μM) induced a concentration-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i by 38 ± 2 nM (n = 76), 117 ± 3.6 nM ( n= 78) and 286 ± 3.4 nM ( n = 85), respectively; comparison of the mean amplitude of the increase in [Ca2+]i, produced by different concentrations of G-1, is shown is Fig. 2D.

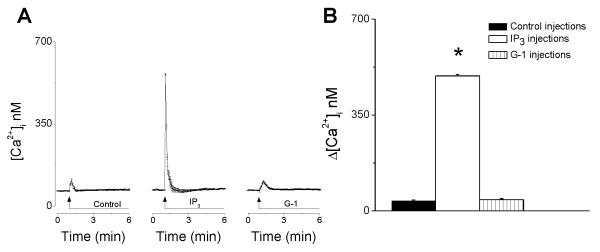

Intracellular microinjection of G-1 does not elicit an increase in [Ca2+]i

Intracellular microinjection of G-1 (10 μM) increased [Ca2+]i by 41± 3.6 nM (n = 6), that was not significantly different from microinjection of control intracellular solution (Δ[Ca2+]i = 37 ± 2.8 nM; P > 0.05, n = 6). As a positive control we used microinjection of inositol 1,4,5-trisphophate (IP3), a second messenger that releases Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store. Intracellular microinjection of IP3 (10 nM) increased [Ca2+]i by 493 ± 5.2 nM in RBMVEC ( n = 6) (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3. Intracellular microinjection of G-1 did not elicit an increase in [Ca2+]i.

A, Averaged traces (n = 6) of Ca2+ responses elicited by intracellular microinjection of control buffer, inositol 1,4,5-trisphophate (IP3) and G-1. IP3, but not G-1 or control buffer, elicited a fast and transitory increase in [Ca2+]i; the response elicited by the intracellular microinjection of G-1 was not significantly different from that produced by the microinjection of control intracellular solution. B, comparison of the averaged amplitudes of increases in [Ca2+]i produced by control buffer, IP3, and G-1. (*) P < 0.05 as compared to basal [Ca2+]i.

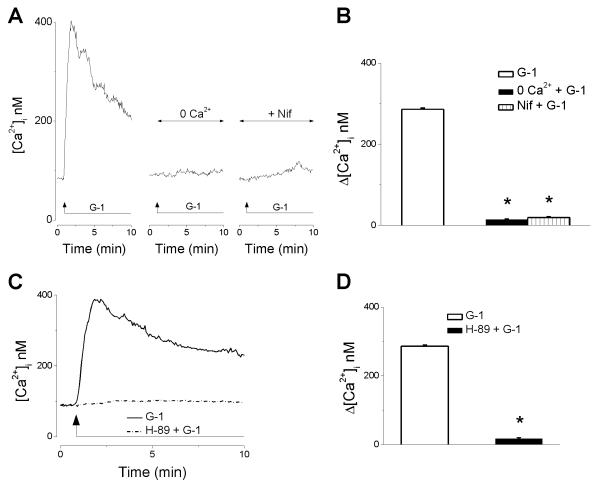

G-1 elicits Ca2+ influx in RBMVEC

In Ca2+-free saline or in the presence of nifedipine (1 μM), an inhibitor of L-type Ca2+ channels, G-1 (10 μM) did not induce an increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4A). This indicates that Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels was responsible for the G-1-induced increase in [Ca2+]. . Δ [Ca2+]i produced by G-1 (10 μM) in Ca2+-free and in the presence of nifedipine was 14 ± 1.3 nM (n = 52) and 19 ± 2.7 nM (n = 46), respectively, as compared to 286 ± 3.4 nM in regular Ca2+-containing saline (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. G-1 elicits Ca2+ influx in RBMVEC via a PKA-dependent mechanism.

A, Representative examples of G-1-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. in regular Ca2+-containing saline, Ca2+-free saline, and in the presence of L-type Ca2+ channels blocker, nifedipine. B, Comparison of the amplitude of increase in [Ca2+]i elicited by G-1 (10 μM) in the each of the conditions mentioned; Ca2+-free (0 Ca2+) and nifedipine abolished the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by G-1. (*) P < 0.05 as compared to G-1-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in Ca2+-containing HBSS. C, Representative examples of the G-1-induced Ca2+ response in the presence (solid line) and absence (dashed line) of the PKA inhibitor, H-89; treatment with H-89 abolished the increased in [Ca2+]i elicited by G-1. D, comparison of the mean amplitude of the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by G-1 in the absence and presence of H-89; (*) P< 0.05 as compared to G-1-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in the absence of H-89.

G-1 increases [Ca2+]i via a PKA-dependent mechanism

Treatment with the PKA antagonist, H-89 (1 μM), markedly decreased the G-1-induced increase in [Ca2+] (Fig. 4C). Δ [Ca2+ i. ]i produced by G-1 (10 μM) in the presence of H-89 was only 17 ± 2.6 nM ( n = 37) as compared to 286 ± 3.4 nM in the absence of the PKA antagonist (Fig. 4D).

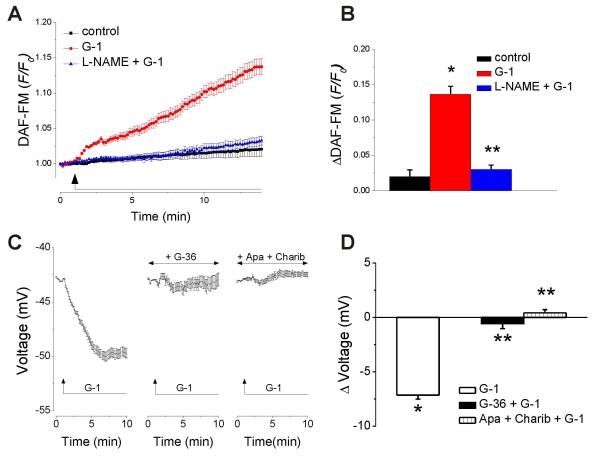

G-1 increases NO production in RBMVEC

NO production in RBMVEC was determined in cells loaded with DAF-FM. G-1 (10 μM) increased the DAF-FM fluorescence; the response was prevented by treatment with NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 100 μM), an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (Fig. 5 A,B). Averaged recordings (n = 26) of DAF-FM fluorescence ratio (F/Fo) in response to G-1 (10 μM) are shown in Fig. 5A, and the comparison of ΔDAFFM in control, untreated, and cells treated with G-1 in the absence and presence of L-NAME are shown in Fig. 5B. G-1 (10 μM) increased the DAF-FM fluorescence ratio by 0.136 ± 0.011 (n = 26) as compared to 0.019 ± 0.009 (n = 22) in untreated cells; in the presence of L-NAME, G-1 increased ΔDAF-FM by only 0.030 ± 0.006, n =33) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. G-1 increases NO production and elicits hyperpolarization in RBMVEC.

A, Averaged DAF-FM fluorescence ratios ± S.E.M. in untreated cells (black trace), cells treated with G-1 (red trace) or G-1 in presence of L-NAME (blue trace); G-1 increased DAF-FM fluorescence, an indicator of NO level. B, Comparison of ΔDAF-FM in control, untreated cells, and cells treated with G-1 in the absence and presence of L-NAME; P < 0.05 as compared to control (*) or to G-1-treated cells in the absence of L-NAME (**). C, Averaged changes in membrane potential ± S.E.M. in response to G-1 (10 μM), in the absence or presence of the GPER antagonist, G-36 (10 μM), or of the apamin and charibdotoxin. Treatment of RBMVEC with G-1 (10 μM) induced a hyperpolarization that was abolished by G-36 (10 μM), or by treatment with apamin (1 μM), and charibdotoxin (100 nM), inhibitors of small and intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa). D, Comparison of the average amplitude of the change in potential produced by G-1 in the absence and presence of G-36, apamin and charibdotoxin. P < 0.05 as compared to control resting potential (*), or to G-1-treated cells (**).

G-1 elicits RBMVEC hyperpolarization

Treatment of RBMVEC with G-1 (10 μM) induced a cellular hyperpolarization that was abolished by the GPER antagonist, G-36 (10 μM), or by treatment with apamin (1 μM) and charibdotoxin (100 nM), inhibitors of small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa), respectively (Fig. 5C). G-1 produced a hyperpolarization with a mean amplitude of −7.14 ± 0.37 mV (n = 37); in the presence of G-36, Δ voltage = − 0.57 ± 0.46 (n = 35); in the presence of apamin and charibdotoxin, Δ voltage = 0.42 ± 0.29 (n = 33) (Fig. 5D).

G-1 increases RBMVEC modulus of elasticity

The calculated modulus of elasticity in the central cellular region of RBMVEC was 12.4 ± 1.9 kPa (n = 7 cells) at 20-30 minutes after exposing the cells to vehicle (HBSS). Treatment of RBMVEC with G-1 (10 μM) increased the modulus of elasticity to 22.1 ± 3.0 kPa (n = 7) during the same time period; this increase in modulus of elasticity by almost 80% was statistically significant (P = 0.035) (Fig. 6A-B); this reflects an increase in RBMVEC stiffness. At 31-40 minutes after treatment, the averaged modulus of elasticity was 8.1 ± 1.1 kPa in control group (n = 7) and 10.9 ± 1.4 kPa (n =10) in G-1-treated group, indicating an increase in modulus of elasticity and cell stiffness by 35%. The averaged modulus of elasticity at 41-50 minutes after exposure to HBSS or G-1 was 8.9 ± 1.9 kPa (n = 6 cells) and 14.8 ± 2.7 kPa (n = 7 cells), indicating an increase in stiffness by 65%. However, the changes in modulus of elasticity/stiffness at 31-40 minutes and 41-50 minutes were not statistically significant (P = 0.117 and P = 0.199, respectively) (Fig. 6A-B). The modulus of elasticity values detected in RBMVEC are within the limits previously reported; elastic modulus of live cells can range from 0.1 kPa to 100 kPa depending on the cell type and probes (cantilevers) used (Mathur et al., 2001 Lee et al., 2011; Arce et al., 2013). A diagram summarizing the mechanisms proposed is illustrated in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6. G-1 increases RBMVEC modulus of elasticity.

A, Illustration of force-distance curves obtained in single RBMVEC. The slopes of the curves were analyzed from the cantilever deflection related to cell indentation. B. Comparison of the calculated averaged modulus of elasticity of RBMVEC, as an indicator of cytoskeletal changes and cell stiffness, at 20-30 min, 31-40 min and 41-50 min after treatment. The modulus of elasticity was higher in G-1 -treated cells than in control- cells (n = 6-10 cells per group); however, the difference was statistically different only at 20-30 min after treatment (*P < 0.05), but not between 31-50 min (**P >0.05).

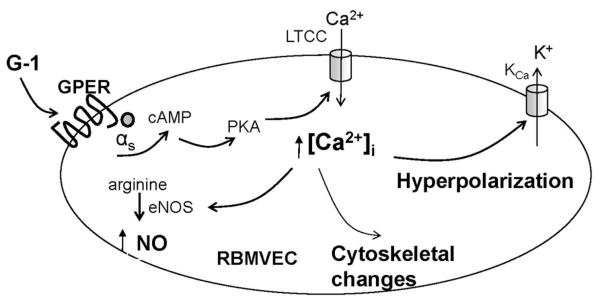

Fig. 7. Diagram summarizing the mechanisms proposed for GPER-mediated effects in RBMVEC.

G-1 acting on GPER increases cAMP, activates protein kinase A (PKA) leading to increase in [Ca2+]i by promoting Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC). The increase in [Ca2+]i leads to activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (K 2+ Ca ) and cellular hyperpolarization, as well as to activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and NO production, and to the cytoskeletal changes leading to increased cell stiffness.

Discussion

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) contributes to several physiological functions controlled by estrogen in the central nervous system (CNS), and cardiovascular system (for review Prossnitz et al., 2008; Olde and Leeb-Lundberg, 2009; Prossnitz and Barton, 2011, 2014). Previous studies indicate that GPER mediates rapid vasodilator responses in various vascular beds by acting on the endothelium and/or vascular smooth muscle cells (Haas et al., 2009; Broughton et al., 2010; Lindsey et al., 2014). Endothelial cells, besides the barrier role, have important signal transduction functions (Pries and Kuebler, 2006); conversely, endothelial dysregulation has been involved in disease states (Favero et al., 2014). Estrogen contributes to neuroprotection by several mechanisms (Sohrabji and Williams, 2013), mainly attributed to ERα and ERβ (Asl et al., 2013). Recently, the GPER was proposed to contribute to the protective effects of estrogen against ischemia/reperfusion injury and to induce vasodilation in cerebral microvessels (Murata et al., 2013). Brain microvascular endothelial cells are an essential component of the blood-brain barrier (Cardoso et al., 2010). Since the mechanisms downstream to GPER activation in endothelial cells of the microvasculature are largely unknown, we used rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVEC) to examine the effects of GPER activation at this level.

The gene encodingGPER (GPR30) was cloned from several tissues (reviewed in Prossnitz et al., 2008) including human endothelial cells (Takada et al., 1997), where it was named Flow-induced Endothelial G protein coupled receptor gene-1, FEG-1. Using western blot analysis, we identified the expression of GPER in RBMVEC at the protein level. Similarly, cultured rat aortic vascular endothelial cells demonstrated persistent GPER (GPR30) expression (Gros et al., 2011).

Emerging evidence supports the complexity of GPER pharmacology (Prossnitz and Barton, 2014). Earlier studies have established 17β-estradiol as the endogenous agonist of GPER (Thomas et al., 2005; Revankar et al., 2006). Interestingly, selective estrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen (Filardo, 2000), as well as the flavonoid ‘phytoestrogens’ genistein and quercetin (Maggiolini, 2004), and selective estrogen receptor downregulators/antagonists such as ICI 182,780 or fulvestrant, are GPER agonists (Prossnitz and Barton, 2014). In RBMVEC, 17β-estradiol elicited a fast and sustained increase in [Ca2+]i that was partially sensitive to the GPER antagonist G-36 (Dennis et al., 2011), indicating that in addition to GPER, 17β-estradiol activated other estrogen receptors. On the other hand, tamoxifen produced a modest and transitory increase in [Ca2+]i which was abolished by the GPER antagonist. To examine the role of GPER in isolation, we employed a widely used selective GPER agonist, G-1 (Bologa et al., 2006; Prossnitz and Barton, 2014).

In RBMVEC, G-1 produced a sustained increase in [Ca2+]I, similar to previous reports, in other cellular models (Revankar et al., 2005; Brailoiu et al., 2007; Ariazi et al., 2010, Tica et al., 2011, Deliu et al., 2012, Meyer et al., 2012; Brailoiu et al., 2013a, b). Vascular endothelial cells may respond to a variety of mechanical and chemical stimuli by generating Ca2+ signals (Moccia, 2012). Since an increase in [Ca2+]i in endothelial cells may be produced by Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ release from internal stores (Yakubu & Leffler, 2002; Moccia et al., 2012), we next explored the source of Ca2+ increase. The sustained increase in Ca2+ produced by G-1 was abolished in Ca2+ free saline or by nifedipine, indicating a critical role for Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels in the response. This is in agreement with earlier reports indicating that the Ca2+ influx elicits a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i, while Ca2+ release from internal stores produces fast and transient increases in [Ca2+]i (Moccia et al., 2012).

The subcellular localization of GPER has been a subject of debate: both intracellular (Revankar et al., 2006) and plasma membrane (Thomas et al., 2005; Filardo et al., 2007) localization of the receptor have been reported. To investigate the location of GPER in RBMVEC, we compared the effect of extracellular versus intracellular administration of G-1. Intracellular microinjection of G-1 did not produce an increase in [Ca2+]i, different from control injections, while the extracellular administration produced a sustained Ca2+ increase. These results support a membrane localization of functional GPER in RBMVEC, similar to that observed in HEK-293 or SKBR3 cells (Thomas et al., 2005; Filardo et al., 2007), but different from the intracellular location of functional GPER in spinal cord neurons (Deliu et al., 2012) and rat myometrial cells (Tica et al., 2011). Our study is the first to report the location of functional GPER in brain microvascular endothelial cells. The functional significance of different subcellular localization in different cellular models remains to be established

GPER may couple with different G proteins: Gs-coupling followed by cAMP-mediated signaling (Filardo et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2005), as well as PLC-mediated increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (Revankar et al., 2005) were reported. A cAMP-dependent mechanism was recently identified in vascular smooth muscle cells of mesenteric arteries (Lindsey et al., 2014) and coronary arteries (Yu et al., 2014), while GPER-mediated signaling in endothelial cells remained unclear. In RBMVEC, the increase in [Ca2+]i elicited by G-1 was prevented by a PKA antagonist, supporting a Gs-coupling mechanism.

In endothelial cells, an increase in [Ca2+]i may activate NO synthase leading to NO production (Fleming et al., 1997). Therefore, we next examined the effect of G-1 on NO production. In RBMVEC, G-1 induced an increase in NO that was abolished by the GPER antagonist, G-36 and by the NOS inhibitor, L-NAME. Similarly, GPER activation increased NO production in other vascular beds such as rat carotid arteries (Broughton et al., 2010), epicardial coronary arteries (Meyer et al., 2010), cerebral arterioles (Murata et al., 2013), and mesenteric arteries (Lindsay et al., 2014). In addition, estrogen and G-1 induced NO release in an immortalized mouse cerebrovascular endothelial cell line (Kitamura et al., 2009). Moreover, in brain microvessels, estrogen and tamoxifen produced vasorelaxation (Florian, 2004). In addition to the vasodilator effect (Furchgott, 1999), NO modulates microvascular permeability (Kubes and Granger, 1992) and inflammatory response (Kubes et al., 1991) while inhibiting platelet activation (Pries and Kuebler, 2006). On the other hand, GPER activation reduces oxidative stress in renal tubules of salt-sensitive female mRen2.Lewis rats (Lindsey and Chappell, 2011).

Measurement of membrane potential indicated that GPER activation promoted hyperpolarization. In endothelial cells, agonist-induced hyperpolarization is most likely due to the activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (KCa) (Feletou, 2009). Endothelial cells express small-conductance (SKCa) and intermediate-conductance (IKCa) Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Kohler et al., 2000). G-1-induced hyperpolarization was abolished by pretreatment with apamin and charybdotoxin consistent with the activation of KCa channels (Burnham et al., 2002; Bychkov et al., 2002). The increase in NO and activation of K+ channels consequent to GPER activation in microvascular endothelial cells may contribute to the protective effects of estrogen on cerebral microcirculation. Endothelial cells possess a cytoskeleton comprising of contractile proteins such as actin, myosin, and tropomyosin that contribute to the shape, elasticity and motor activities (Favero et al., 2014). An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ has been shown to modulate cytoskeletal reorganization (Park et al., 1999; Tiruppathi et al., 2002). Since GPER activation increased [Ca2+]i, we assessed the effects of G-1, the selective GPER agonist, on the elastic modulus, an indicator of underlying structural force and cell stiffness, in live RBMVEC.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been proven an invaluable tool to examine the nanomechanics and function of living endothelial cells (Hillebrand et al., 2008; Fels et al., 2014). Previous studies found a good correlation between the cytoskeletal changes and cell nanomechanics (Arce et al., 2008, 2013). Agents like thrombin, which disrupt barrier function, increase the accumulation of F-actin stress fibers and cell stiffness in the central region (Arce et al., 2008). Our AFM studies indicate that G-1 increases modulus of elasticity in the central region 20-30 minutes after treatment. Several conditions have been shown to modulate the cell elasticity. For example, aldosterone high plasma sodium and TNF-α increased cell stiffness (Oberleithner et al., 2006; Oberleithner et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011). On the other hand, 17β-estradiol increased elasticity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Hillebrand et al., 2006). Nevertheless, that effect occurred over a few days, suggesting the involvement of nuclear receptors (Hillebrand et al., 2006).

Interestingly, aldosterone was reported to have a biphasic effect on endothelial cell stiffness; it decreased stiffness in the first 15 minutes and increased it at 20-30 min (Fels et al., 2010a). Moreover, the response was not affected by spironolactone, indicating that it was mediated by a receptor distinct from mineralocorticoid receptors. In addition, aldosterone was shown to increase NO within 10 min (Fels et al., 2010b). Since aldosterone was found to activate GPER in endothelial vascular smooth muscle cells (Gros et al., 2011, 2013) as well as in neurons (Brailoiu et al., 2013) relatively recently, the mechanisms described here may also have implications for aldosterone signaling in brain microvascular endothelial cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. James Shaw (Bruker Nano Surfaces Division, Goleta, CA) for help with atomic force microscopy. This study was supported by startup funds from Jefferson School of Pharmacy (GCB), and NIH grant P30 DA 013429 from the Department of Health and Human Services. All experiments had the institutional approval.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

cytosolic Ca2+ concentration

- GPER

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor

- L-NAME

NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- NO

nitric oxide

- RBMVEC

rat brain microvascular endothelial cells

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ, CGTP Collaborators The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariazi EA, Brailoiu E, Yerrum S, Shupp HA, Slifker MJ, Cunliffe HE, Black MA, Donato AL, Arterburn JB, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ, Jordan VC. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 inhibits proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2010;70:1184–1194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce FT, Whitlock JL, Birukova AA, Birukov KG, Arnsdorf MF, Lal R, Garcia JG, Dudek SM. Regulation of the micromechanical properties of pulmonary endothelium by S1P and thrombin: role of cortactin. Biophysical journal. 2008;95:886–894. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce FT, Meckes B, Camp SM, Garcia JG, Dudek SM, Lal R. Heterogeneous elastic response of human lung microvascular endothelial cells to barrier modulating stimuli. Nanomedicine: nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2013;9:875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asl SZ, Khaksari M, Khachki AS, Shahrokhi N, Nourizade S. Contribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the brain response to traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 2013;119:353–361. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.JNS121636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nature chemical biology. 2006;2:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu E, Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Mizuo K, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ. Distribution and characterization of estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 in the rat central nervous system. The Journal of endocrinology. 2007;193:311–321. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu E, Deliu E, Sporici RA, Benamar K, Brailoiu GC. HIV-1-Tat excites cardiac parasympathetic neurons of nucleus ambiguus and triggers prolonged bradycardia in conscious rats. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2014;306:R814–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00529.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Gurzu B, Gao X, Parkesh R, Aley PK, Trifa DI, Galione A, Dun NJ, Madesh M, Patel S, Churchill GC, Brailoiu E. Acidic NAADP-sensitive calcium stores in the endothelium: agonist-specific recruitment and role in regulating blood pressure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:37133–37137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.169763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Oprea TI, Zhao P, Abood ME, Brailoiu E. Intracellular cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors are activated by anandamide. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29166–29174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.217463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Arterburn JB, Oprea TI, Chitravanshi VC, Brailoiu E. Bradycardic effects mediated by activation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in rat nucleus ambiguus. Experimental physiology. 2013a;98:679–691. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Benamar K, Arterburn JB, Gao E, Rabinowitz JE, Koch WJ, Brailoiu E. Aldosterone increases cardiac vagal tone via G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor activation. The Journal of physiology. 2013b;591:4223–4235. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner T, Hulser DF, Strasser RJ. Comparative measurements of membrane potentials with microelectrodes and voltage-sensitive dyes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1984;771:208–216. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton BR, Miller AA, Sobey CG. Endothelium-dependent relaxation by G protein-coupled receptor 30 agonists in rat carotid arteries. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2010;298:H1055–1061. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00878.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham MP, Bychkov R, Feletou M, Richards GR, Vanhoutte PM, Weston AH, Edwards G. Characterization of an apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channel in porcine coronary artery endothelium: relevance to EDHF. British journal of pharmacology. 2002;135:1133–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov R, Burnham MP, Richards GR, Edwards G, Weston AH, Feletou M, Vanhoutte PM. Characterization of a charybdotoxin-sensitive intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in porcine coronary endothelium: relevance to EDHF. British journal of pharmacology. 2002;137:1346–1354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso FL, Brites D, Brito MA. Looking at the blood-brain barrier: molecular anatomy and possible investigation approaches. Brain research reviews. 2010;64:328–363. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliu E, Brailoiu GC, Arterburn JB, Oprea TI, Benamar K, Dun NJ, Brailoiu E. Mechanisms of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-mediated spinal nociception. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2012;13:742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MK, Field AS, Burai R, et al. Identification of a GPER/GPR30 antagonist with improved estrogen receptor counterselectivity. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2011;127:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favero G, Paganelli C, Buffoli B, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Endothelium and its alterations in cardiovascular diseases: life style intervention. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:801896. doi: 10.1155/2014/801896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feletou M. Calcium-activated potassium channels and endothelial dysfunction: therapeutic options? British journal of pharmacology. 2009;156:545–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fels J, Callies C, Kusche-Vihrog K, Oberleithner H. Nitric oxide release follows endothelial nanomechanics and not vice versa. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2010a;460:915–923. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0871-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fels J, Oberleithner H, Kusche-Vihrog K. Menage a trois: aldosterone, sodium and nitric oxide in vascular endothelium. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010b;1802:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fels J, Jeggle P, Liashkovich I, Peters W, Oberleithner H. Nanomechanics of vascular endothelium. Cell and tissue research. 2014;355:727–737. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1853-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR., Jr. Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Molecular endocrinology. 2000;14:1649–1660. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Frackelton AR, Jr., Bland KI. Estrogen action via the G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-mediated attenuation of the epidermal growth factor receptor-to-MAPK signaling axis. Molecular endocrinology. 2002;16:70–84. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo E, Quinn J, Pang Y, Graeber C, Shaw S, Dong J, Thomas P. Activation of the novel estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) at the plasma membrane. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3236–3245. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Thomas P. Minireview: G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1, GPER-1: its mechanism of action and role in female reproductive cancer, renal and vascular physiology. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2953–2962. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I, Bauersachs J, Busse R. Calcium-dependent and calcium-independent activation of the endothelial NO synthase. Journal of vascular research. 1997;34:165–174. doi: 10.1159/000159220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian M, Lu Y, Angle M, Magder S. Estrogen induced changes in Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. Steroids. 2004;69:637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor: discovery, early studies, and identification as nitric oxide. Bioscience reports. 1999;19:235–251. doi: 10.1023/a:1020537506008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros R, Ding Q, Liu B, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. Aldosterone mediates its rapid effects in vascular endothelial cells through GPER activation. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2013;304:C532–540. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00203.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros R, Ding Q, Sklar LA, Prossnitz EE, Arterburn JB, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. GPR30 expression is required for the mineralocorticoid receptor-independent rapid vascular effects of aldosterone. Hypertension. 2011;57:442–451. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, Damjanovic M, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Mueller-Guerre L, Marjon NA, Gut A, Minotti R, Meyer MR, Amann K, Ammann E, Perez-Dominguez A, Genoni M, Clegg DJ, Dun NJ, Resta TC, Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Regulatory role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor for vascular function and obesity. Circulation research. 2009;104:288–291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas E, Meyer MR, Schurr U, Bhattacharya I, Minotti R, Nguyen HH, Heigl A, Lachat M, Genoni M, Barton M. Differential effects of 17beta-estradiol on function and expression of estrogen receptor alpha, estrogen receptor beta, and GPR30 in arteries and veins of patients with atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2007;49:1358–1363. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand U, Hausberg M, Stock C, Shahin V, Nikova D, Riethmüller C, Kliche K, Ludwig T, Schillers H, Schneider SW, Oberleithner H. 17β-estradiol increases volume, apical surface and elasticity of human endothelium mediated by Na+/H+ exchange. Cardiovascular research. 2006;69:916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isensee J, Meoli L, Zazzu V, Nabzdyk C, Witt H, Soewarto D, Effertz K, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Busch D, Adler T, de Angelis MH, Irgang M, Otto C, Noppinger PR. Expression pattern of G protein-coupled receptor 30 in LacZ reporter mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1722–1730. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura N, Araya R, Kudoh M, Kishida H, Kimura T, Murayama M, Takashima A, Sakamaki Y, Hashikawa T, Ito S, Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T, Wess J, Yamada M. Beneficial effects of estrogen in a mouse model of cerebrovascular insufficiency. PloS one. 2009;4:e5159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler R, Degenhardt C, Kuhn M, Runkel N, Paul M, Hoyer J. Expression and function of endothelial Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels in human mesenteric artery: A single-cell reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and electrophysiological study in situ. Circulation research. 2000;87:496–503. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.6.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima H, Nakatsubo N, Kikuchi K, Kawahara S, Kirino Y, Nagoshi H, Hirata Y, Nagano T. Detection and imaging of nitric oxide with novel fluorescent indicators: diaminofluoresceins. Analytical chemistry. 1998;70:2446–2453. doi: 10.1021/ac9801723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubes P, Granger DN. Nitric oxide modulates microvascular permeability. The American journal of physiology. 1992;262:H611–615. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubes P, Suzuki M, Granger DN. Nitric oxide: an endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:4651–4655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Zaske AM, Novellino T, Danila D, Ferrari M, Conyers J, Decuzzi P. Probing the mechanical properties of TNF-α stimulated endothelial cell with atomic force microscopy. International journal of nanomedicine. 2011;6:179–195. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SH, Chappell MC. Evidence that the G protein-coupled membrane receptor GPR30 contributes to the cardiovascular actions of estrogen. Gender medicine. 2011;8:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SH, Liu L, Chappell MC. Vasodilation by GPER in mesenteric arteries involves both endothelial nitric oxide and smooth muscle cAMP signaling. Steroids. 2014;81:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SH, Yamaleyeva LM, Brosnihan KB, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC. Estrogen receptor GPR30 reduces oxidative stress and proteinuria in the salt-sensitive female mRen2. Lewis rat. Hypertension. 2011;58:665–671. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiolini M, Vivacqua A, Fasanella G, Recchia AG, Sisci D, Pezzi V, Montanaro D, Musti AM, Picard D, Andà S. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 mediates c-fos up-regulation by 17beta-estradiol and phytoestrogens in breast cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:27008–27016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur AB, Collinsworth AM, Reichert WM, Kraus WE, Truskey GA. Endothelial, cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle exhibit different viscous and elastic properties as determined by atomic force microscopy. J Biomech. 2001;34:1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MR, Baretella O, Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Dilation of epicardial coronary arteries by the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor agonists G-1 and ICI 182,780. Pharmacology. 2010;86:58–64. doi: 10.1159/000315497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MR, Field AS, Kanagy NL, Barton M, Prossnitz ER. GPER regulates endothelin-dependent vascular tone and intracellular calcium. Life sciences. 2012;91:623–627. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moccia F, Berra-Romani R, Tanzi F. Update on vascular endothelial Ca(2+) signalling: A tale of ion channels, pumps and transporters. World journal of biological chemistry. 2012;3:127–158. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v3.i7.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Dietrich HH, Xiang C, Dacey RG., Jr. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor agonist improves cerebral microvascular function after hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in male and female rats. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:779–785. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.678177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberliethner H, Riethmüller C, Schillers H, MacGregor GA, Wardener HE, Hausberg M. Plasma sodium stiffens vascular endothelium and reduces nitric oxide release. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberleithner H, Riethmüller C, Ludwig T, Shahin V, Stock C, Schwab A, Hausberg M, Kusche K, Schillers H. Differential action of steroid hormones on human endothelium. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:1926–1932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olde B, Leeb-Lundberg LM. GPR30/GPER1: searching for a role in estrogen physiology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owman C, Blay P, Nilsson C, Lolait SJ. Cloning of human cDNA encoding a novel heptahelix receptor expressed in Burkitt’s lymphoma and widely distributed in brain and peripheral tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:285–292. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Okayama N, Gute D, Krsmanovic A, Battarbee H, Alexander JS. Hypoxia/aglycemia increases endothelial permeability: role of second messengers and cytoskeleton. The American journal of physiology. 1999;277:C1066–1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.6.C1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries AR, Kuebler WM. Normal endothelium. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2006:1–40. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32967-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Barton M. The G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in health and disease. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2011;7:715–726. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Estrogen biology: new insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2014;389:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Arterburn JB. GPR30: a novel therapeutic target in estrogen-related disease. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2008;29:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Williams M. Stroke neuroprotection: oestrogen and insulin-like growth factor-1 interactions and the role of microglia. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2013;25:1173–1181. doi: 10.1111/jne.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y, Kato C, Kondo S, Korenaga R, Ando J. Cloning of cDNAs encoding G protein-coupled receptor expressed in human endothelial cells exposed to fluid shear stress. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1997;240:737–741. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:624–632. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tica AA, Dun EC, Tica OS, Gao X, Arterburn JB, Brailoiu GC, Oprea TI, Brailoiu E. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1-mediated effects in the rat myometrium. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2011;301:C1262–1269. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00501.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruppathi C, Minshall RD, Paria BC, Vogel SM, Malik AB. Role of Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Vascular pharmacology. 2002;39:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu MA, Leffler CW. L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells and ET-1 biosynthesis. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2002;283:C1687–1695. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00071.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Li F, Klussmann E, Stallone JN, Han G. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER) mediates relaxation of coronary arteries via cAMP/PKA-dependent activation of MLCP. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;307:E398–407. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00534.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]