Abstract

In this work iminyl σ-radical formation in several one-electron oxidized cytosine analogs including 1-MeC, cidofovir, 2′-deoxycytidine (dCyd), and 2′-deoxycytidine 5′-monophosphate (5′-dCMP) were investigated in homogeneous aqueous (D2O or H2O) glassy solutions at low temperatures employing electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy. Employing density functional theory (DFT) (DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* method), the calculated hyperfine coupling constant (HFCC) values of iminyl σ-radical agree quite well with the experimentally observed ones thus confirming its assignment. ESR and DFT studies show that the cytosine-iminyl σ-radical is a tautomer of the deprotonated cytosine π-cation radical (cytosine π-aminyl radical, C(N4-H)•). Employing 1-MeC samples at various pHs ranging ca. 8 to ca. 11, ESR studies show that the tautomeric equilibrium between C(N4-H)• and the iminyl σ-radical at low temperature is too slow to be established without added base. ESR and DFT studies agree that in the iminyl-σ radical, the unpaired spin is localized to the exocyclic nitrogen (N4) in an in-plane pure p-orbital. This gives rise to an anisotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling (Azz = 40 G) from N4 and a near isotropic β-nitrogen coupling of 9.7 G from the cytosine ring nitrogen at N3. Iminyl σ-radical should exist in its N3-protonated form as the N3-protonated iminyl σ-radical is stabilized in solution by over 30 kcal/mol (ΔG= −32 kcal/mol) over its conjugate base, the N3-deprotonated form. This is the first observation of an isotropic β-hyperfine ring nitrogen coupling in an N-centered DNA-radical. Our theoretical calculations predict that the cytosine iminyl σ-radical can be formed in dsDNA by a radiation-induced ionization–deprotonation process that is only 10 kcal/mol above the lowest energy path.

Introduction

High energy radiation impinging on DNA causes random ionization events in approximate proportions to the number of valence electrons present at any DNA site. Thus, formation of holes takes place at each of the bases as well as at the sugar-phosphate backbone forming G•+, A•+, C•+, T•+, and [sugar-phosphate]•+.1 – 8 Both purine and pyrimidine base cation radicals have been extensively studied experimentally in aqueous solution at room temperature by pulse radiolysis and flash photolysis as well as by electron spin resonance (ESR) at low temperatures in monomers, oligomers of defined sequences, polynucleotides, and in highly polymeric DNA (e.g., salmon sperm, calf thymus etc.).1 – 14 The mechanistic pathways of formation of DNA damage products from these initially-produced cation radicals are critically influenced by the electronic nature (π- or σ-) of DNA-radicals. Calculations employing density functional theory (DFT) predict that formation of both π- or σ-type DNA cation radicals may be observed in DNA bases and analogs.15 The DNA base cation radicals, G•+, A•+, C•+, and T•+ have been found to be only π-type cation radicals in irradiated DNA and its model systems.7, 15 DFT calculations, however, predict that the σ-states for one-electron oxidized pyrimidine DNA bases are energetically close to the corresponding lower lying π-states.15 Experimental evidence on formation of σ-type radicals has been presented in one-electron oxidized pyrimidine derivatives having modified nucleobases (e.g., 2-thiothymine,16 6-azauracil, 6-azathymine, and 6-azacytosine17).

For cytosine base π-cation radical (C•+) produced via one-electron oxidation by SO4•− in monomers, pulse radiolysis studies have suggested that deprotonation from the exocyclic amine group to the surrounding solvent (scheme 1) leads to the formation of a neutral cytosine π-aminyl radical (C(N4-H)•).9, 18, 19 Time-resolved ESR studies of 1-methylcytosine (1-MeC) in H2O by Beckert et al. had presented evidence of the 1-MeC π-cation radical formation by electron transfer from 1-MeC to the triplet state of anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate.20 The 1-MeC π-cation radical, subsequently, deprotonated to the π-aminyl radical (1-MeC(N4-H)•) which showed a 17.4 G doublet from the exocyclic N-H proton; further confirmation of this assignment came from studies in D2O where this doublet collapsed owing to the exchangeable nature of the exocyclic N-H proton.20 Furthermore, pulse radiolysis studies in aqueous solutions of SeO3•−-mediated one-electron oxidized calf thymus DNA have proposed that σ-iminyl radical from cytosine could be as an intermediate to guanine cation radical formation.21

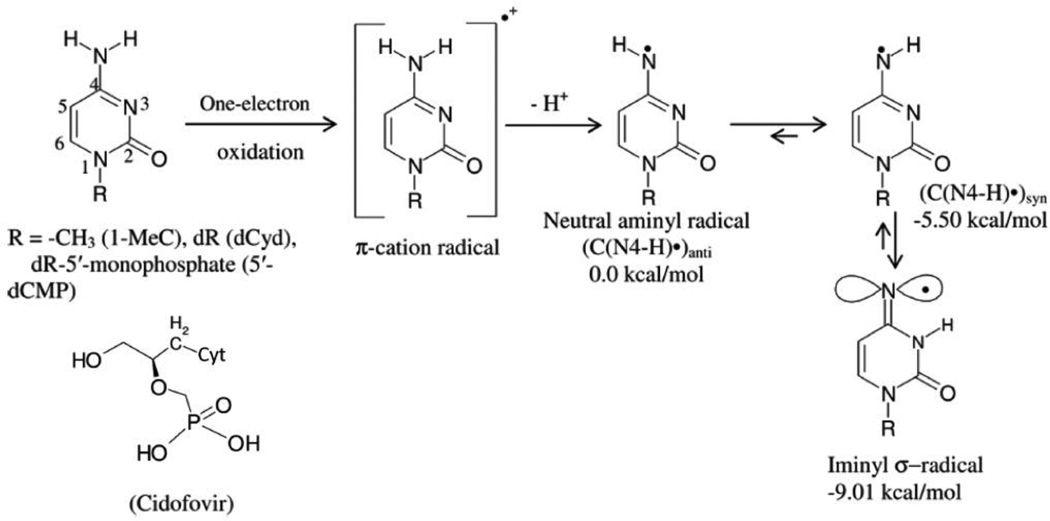

Scheme 1.

Formation of cytosine π-cation radical via one-electron oxidation of cytosine monomers. The cytosine π-cation radical, via deprotonation and by subsequent tautomerization, leads to the formation of iminyl radical, which is a σ radical by nature. The atom numbering scheme of the cytosine base is shown. The relative stabilities of C(N4-H)• syn, C(N4-H)•anti, and iminyl σ-radical in kcal/mol are provided. Optimization of the geometries of these radicals along with their energy values employing optimized structures were obtained with the aid of DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* method.

Steady state or continuous wave ESR (CW ESR) studies using 1-MeC as a model of a cytosine monomer,9, 19 have suggested that the neutral π-aminyl radical formed by deprotonation of the π-cation radical led to a subsequent radical production. The experimentally obtained hyperfine coupling constant (HFCC) values of this new radical were compared to those of DFT-calculated nitrogen and hydrogen HFCC for several aminyl and iminyl radicals.9, 19 This comparison of HFCC values led to the tentative assignment of the new radical species to the iminyl σ-radical9, 19 which is a tautomer of the neutral π-aminyl radical (scheme 1). This tentative assignment has not been confirmed to date.

Various cytosine analogs (e.g., 1-MeC, cidofovir, the nucleoside 2′-deoxycytidine (dCyd), and the nucleotide (5'-dCMP)) are investigated in this work. Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopic studies show formation of the iminyl σ-radical (scheme 1) in these one-electron oxidized cytosine analogs in homogeneous aqueous (D2O or H2O) glassy solutions at low temperatures and at higher pH (ca. 10 and above). Calculations employing density functional theory (DFT) support the ESR spectral assignment of the iminyl σ-radical. These results clearly show that the cytosine-iminyl σ-radical is a tautomer of the neutral cytosine π-aminyl radical, C(N4-H)• (scheme 1) and the C(N4-H)• formation occurs through deprotonation of the cytosine base π-cation radical at the exocyclic amine (scheme 1). The combination of ESR studies and DFT calculations identify both species (C(N4-H)• and cytosine-iminyl σ-radical) involved in the tautomeric equilibria. At low temperature, the shift in the tautomeric equilibria to the cytosine-iminyl σ-radical is aided by the presence of a proton acceptor, for example, −OH. These results show that the unpaired spin in the iminyl-σ radical is localized to the exocyclic nitrogen (N4) in an in-plane pure p-orbital which gives rise to an anisotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling from N4 and a near isotropic β-hyperfine coupling from the nitrogen (N3) on the cytosine ring. Previous spin trapped DNA-radicals have shown nitrogen couplings that are β to the nitroxide nitrogen.22 However, this is the first example of near isotropic β-hyperfine ring nitrogen coupling in a DNA base radical itself. In addition, theoretical calculations are employed to clarify the reaction energies of iminyl σ-radical-induced oxidation of G in a one-electron oxidized G:C base pair.

Materials & Methods

Compounds

1-methylcytosine (1-MeC, scheme 1) and 2'-deoxycytidine (dCyd) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA). 1-MeC was also procured from Astatech Inc. (Bristol, PA, USA). Cidofovir (scheme 1) was purchased from ADooQ Bioscience (Irvine, CA, USA). Lithium chloride (LiCl) (ultra dry, 99.995% (metals basis)) and 2'-deoxycytidine 5'-monophosphate (5'-dCMP) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Deuterium oxide (D2O) (99.9 atom % D) was purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company Inc. (Milwaukee, WI, USA). Potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) was procured from Mallinckrodt, Inc. (Paris, KY, USA). All compounds were used without further purification.

Glassy sample preparation

As per our ongoing studies on various model systems of DNA and RNA,7, 8, 23 – 35 the homogeneous glassy samples of 1-MeC, cidofovir, dCyd, and 5'-dCMP were prepared as follows:

Preparation of homogeneous solutions: By dissolving 0.6 to 9.8 mg/ml of the compound in either 7.5 M LiCl in D2O or in H2O and in the presence of K2S2O8 (6 to 20 mg/ml), its homogeneous solutions were prepared. K2S2O8 was added as an electron scavenger so that only the formation of the one-electron oxidized species and its subsequent reactions can be followed employing ESR spectroscopy.

pH adjustments: The pH of these homogeneous solutions either in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O or in 7.5 M LiCl/H2O was adjusted to the range of ca. 8 to ca. 11. These pH adjustments were performed by quickly adding µL amounts 1 M NaOH under ice-cold conditions. Owing to the high ionic strength (7.5 M LiCl), pH meters would not provide accurate pH measurements of these solutions. Hence, pH papers were employed to measure the pH values of these solutions and these pH values are approximate.

Preparation of glassy samples and their storage: These pH-adjusted homogenous solutions were thoroughly bubbled with nitrogen gas. These solutions were then immediately drawn into 4 mm Suprasil quartz tubes (Catalog no. 734-PQ-8, WILMAD Glass Co., Inc., Buena, NJ, USA). By rapidly immersing the quartz tubes containing these solutions in liquid nitrogen (77 K), these solutions were cooled to 77 K. As a result of the rapid cooling at 77 K, the homogeneous liquid solutions form transparent homogeneous glassy solutions. For γ-irradiation and subsequent progressive annealing experiments, these homogeneous glassy solutions were used. All glassy samples were stored at 77 K in Teflon containers in the dark.

γ-Irradiation of glassy samples and their storage

Following our ongoing efforts on various DNA and RNA model systems,8, 23 – 35 the glassy samples were γ (60Co)-irradiated (absorbed dose = 1.4 kGy) at 77 K and stored at 77 K in Teflon containers in the dark.

Annealing of glassy samples

We have employed a variable temperature assembly that passed liquid nitrogen cooled dry nitrogen gas past a thermister and over the sample for the annealing as per our previous studies.8, 23 – 35 Each glassy sample has been progressively annealed in the range (140 – 170) K for 15 min. The matrix radical Cl2•− causes one-electron oxidation of the solute (e.g., 1-MeC) via annealing and thus enables us to study only the solute cation radical production and its subsequent reactions directly via ESR spectroscopy.

Electron Spin Resonance

As per our ongoing studies on DNA and RNA-radicals,7, 8, 23 – 35 a Varian Century Series X-band (9.3 GHz) ESR spectrometer with an E-4531 dual cavity, 9-inch magnet, and a 200 mW Klystron was used and Fremy’s salt (gcenter = 2.0056, A(N) = 13.09 G) was employed for the field calibration. All ESR spectra have been recorded at 77 K and at 40 dB (20 µ W). Spectral recording at 77 K maximizes signal height and allows for comparison of signal intensities.

Following our works on DNA and RNA-radicals,7, 8, 23 – 35 the anisotropic simulations of the experimentally recorded ESR spectra were carried out by employing the Bruker programs (WIN-EPR and SimFonia). The ESR parameters (e.g., hyperfine coupling constant (HFCC) values, linwidth, etc.) were adjusted to obtain the “best fit” simulated spectrum that matched the experimental ESR spectrum well (see supporting information Figure S1 and our works26, 28, 29, 35).

Calculations based on DFT

B3LYP functional and 6-31G* as the basis set implemented in the Gaussian 09 suit of program,36 have been employed to carry out the theoretical calculations such as geometry optimizations, calculations of the hyperfine coupling constant (HFCC) values of radicals in 1-MeC (see supporting information). The calculated HFCC values employing B3LYP/6-31G* method agree well with those obtained using experiment.7, 8, 10, 23 – 35, 37 The GaussView38 program was used to plot the spin densities and molecular structures.

For localization of the radical site of cytosine iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized G:C base pair, DFT/ωb97x/6-31++G(d) method was employed for geometry optimization to study the reaction energies along with spin density distribution plots. The integral equation formalism polarized continuum model39 (IEF-PCM) as implemented in Gaussian 09 was used to treat the effect of full solvent. The group of Head-Gordon developed ωb97x functional40, 41 and this functional was observed to be very successful for the calculations of various properties of molecules in different spin states.35, 42

Results and Discussion

ESR studies

1. Formation of the iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized 1-MeC, cidofovir, dCyd, and 5′-dCMP

In Figure 1, we present the ESR spectral (spectra recorded at 77 K) evidence showing formation of the iminyl σ-radical in matched homogeneous glassy (7.5 M LiCl in D2O) samples of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC, cidofovir, dCyd, and 5′-dCMP. We note here that cidofovir, a cytosine nucleotide analog (scheme 1), is an antiviral agent that is widely used to treat cytomegalovirus infection in the retina of the patients with AIDS43, 44.

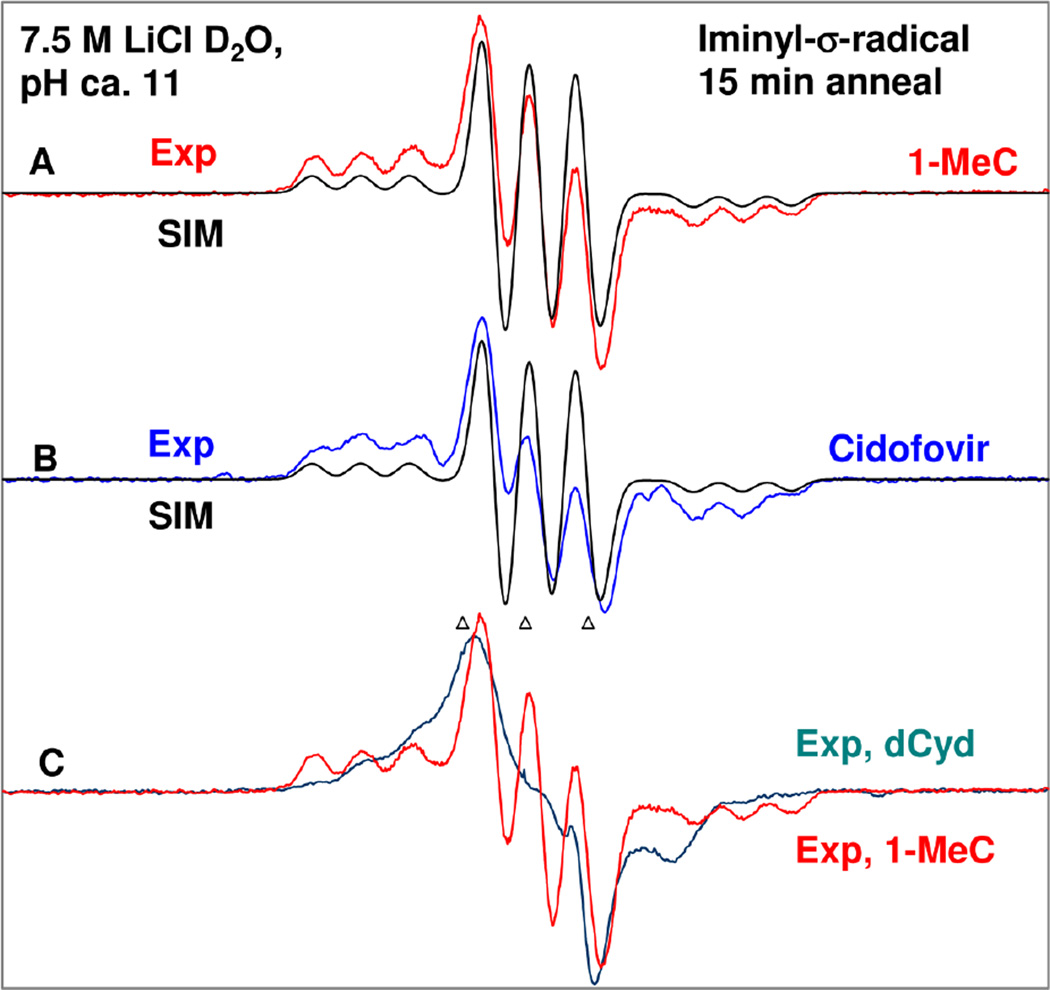

Figure 1.

ESR spectra of iminyl σ-radical formed in γ-irradiated (dose = 1.4 kGy at 77 K) matched glassy samples (2 mg/ml each) of (A) 1-MeC (red), (B) cidofovir (blue), and (C) dCyd (teal) in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O with electron scavenger K2S2O8 (8 mg/ml in each sample), pH ca. 11 via annealing at 160 – 165 K for 15 min after one-electron oxidation of the cytosine base by Cl2•−. The simulated spectra (black) due to iminyl σ-radical of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC (A) and cidofovir (B) are placed underneath the experimental spectra. For simulation parameters see text. (C) The experimentally recorded spectrum of one-electron oxidized dCyd (teal) is shown in Figure 1(C). The experimentally obtained iminyl σ-radical spectrum from 1-MeC (red, Figure 1(A)) has been superimposed on this spectrum for comparison. All ESR spectra shown in Figures A to C were recorded at 77 K. The three reference markers in this figure and in subsequent figures are Fremy’s salt resonances with central marker is at g = 2.0056 and each of three markers is separated from one another by 13.09 G.

The ESR spectrum (red) from a γ-irradiated (absorbed dose = 1.4 kGy, γ-irradiation at 77 K) homogeneous glassy (7.5 M LiCl/D2O, pH ca. 11) sample of 1-MeC (2 mg/ml) in the presence of K2S2O8 as electron scavenger obtained via annealing at 165 K for 15 min in the dark is presented in Figure 1A. The spectra from matched samples of cidofovir (blue) and dCyd (teal) also at pH ca. 11 are presented in Figures 1(B) and 1(C) respectively. The ESR spectra obtained from matched samples of 1-MeC (pH ca. 10) and cidofovir (pH ca. 11) via progressive annealing in the dark and in the temperature range (77 K (immediately after γ-irradiation at 77 K) to 170 K) are presented in the supporting information Figures S2 to S7.

Following our ongoing work on formation of one-electron oxidized species by Cl2•− in DNA model structures,8, 23–32, 34, 35 progressive annealing of these samples at and above 140 K softens the glass so that the migration of Cl2•− and its reaction with the solute, for example, 1-MeC, produces only one-electron oxidized 1-MeC. Therefore, spectrum 1(A) (red) has been obtained after further annealing of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC sample at 165 K. In other words, the spectrum obtained in Figure 1(A) is due to a radical species that is produced from the 1-MeC π-cation radical or its deprotonated species i.e, π-aminyl radical (1-MeC(N4-H)•). Employing pulse radiolysis in aqueous solution at ambient temperature, the pKa of the cytosine π-cation radical (C•+) in dCyd has reported as 4.12 Also, theoretically (DFT) predicted pKa values of C•+ in dCyd are 3.445 and 3.6 to 4.246 – the latter being more accurate. Since C•+ produces C(N4-H)• by fast reversible deprotonation from the exocyclic amine group (scheme 1),9, 18 – 20, 45, 46 the radical observed in Figure 1 after annealing at 165 K and at pH 10 and above should be produced from C(N4-H)• (scheme 1) and is supported by our results is Figure 2. We have assigned this radical species as iminyl σ-radical (scheme 1). Justification of this radical assignment is provided below.

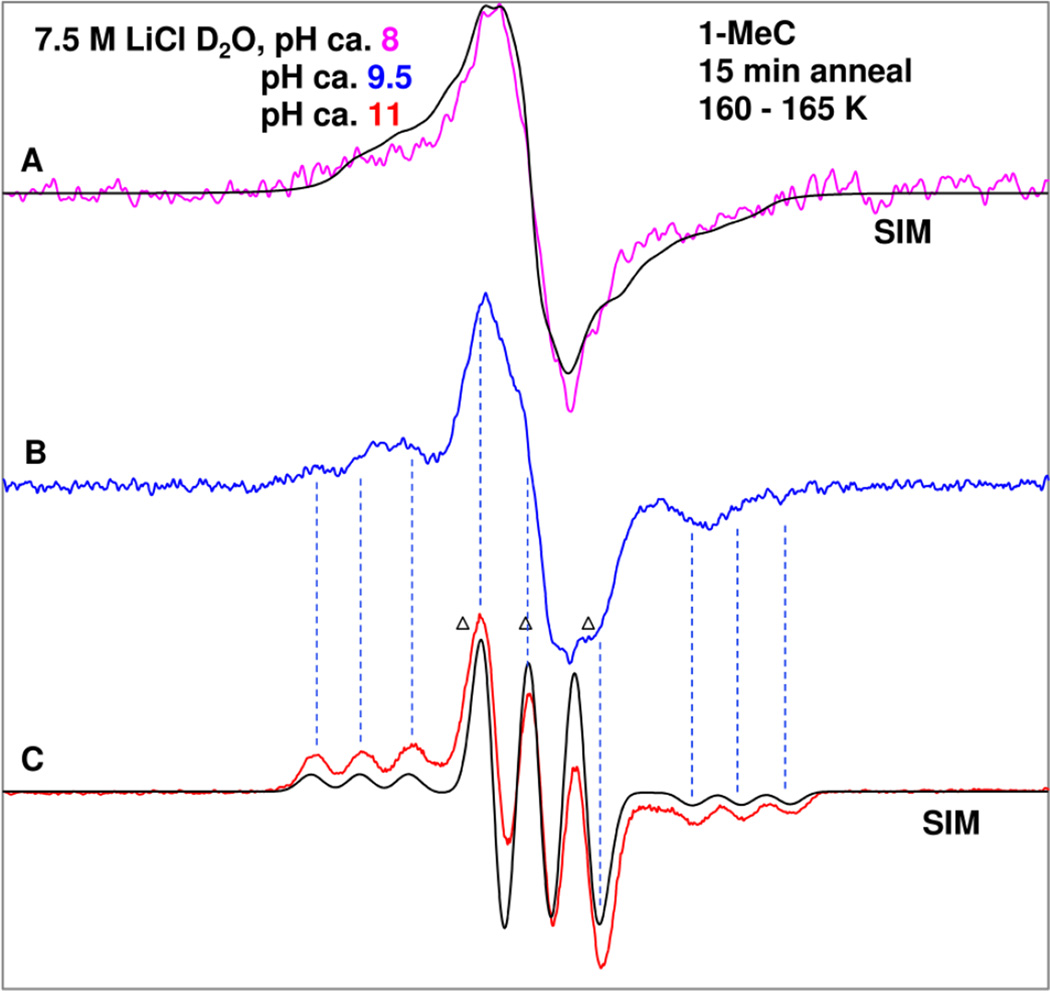

Figure 2.

ESR spectra obtained from matched 1-MeC samples [concentration of 1-MeC in each sample = 2 mg/ml in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O] in the presence of the electron scavenger K2S2O8 (8 mg/ml in each sample). Each sample has been γ-irradiated (absorbed dose = 1.4 kGy at 77 K), subsequently annealed to 160 to 165 K for 15 min in the dark at various pHs (A) pH ca. 8 (pink), (B) pH ca. 9.5 and (C) pH ca. 11 (red, spectrum in Figure 1(C)). The simulated spectra (black) due to the π-aminyl radical (1-MeC(N4-H)•) in (A) as well as owing to the iminyl σ-radical of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC in (C) respectively are placed underneath the experimental spectra. The line components of the red (or, black) spectrum in (C) are visible in (B) (see dotted lines). See text for the details of simulation. All ESR spectra are recorded at 77 K.

Assignment of spectra in Figure 1(A) to the iminyl σ-radical in 1-MeC

It is evident from the hyperfine splittings, line intensities, and g-value of the experimentally obtained spectrum (red) shown in Figure 1(A) that this ESR spectrum results to two nitrogen HFCC values – one anisotropic N-atom HFCC and one nearly isotropic N-atom HFCC. This spectrum has been simulated by employing the ESR parameters (Axx, Ayy, and Azz) for two nitrogens with (40.0, 0, 0) G and (10.2, 9.5, 9.5) G along with gxx, gyy, gzz values of (2.0023, 2.0043, 2.0043), isotropic linewidth of 5 G and mixed Lorentzian/Gaussian =1. The simulated spectrum (black) is superimposed on the experimentally obtained spectrum (blue) in Figure 1(A) and both spectra match nicely. Our DFT calculations show that these couplings are in agreement only with an iminyl σ-radical (vide infra).

The experimental and theoretical work by von Sonntag et al.9, 19 for the CW ESR spectrum of SO4•−-induced one-electron oxidized 1-MeC in aqueous solution at room temperature had presented the isotropic g-value (2.0035) indicative of a N-centered radical and the fit of DFT calculations of N-atom isotropic hyperfine couplings to their experimental values (Aiso (N3) = 11.8 G; Aiso (N4) = 11.6 G).19 We also note here that the isotropic HFCC value of the nitrogen with radical site in other iminyl radicals (e.g., 9-fluorenoneiminyl radical (9.7 G)47, dialkyl as well as diaryl iminyl radical (9.1 to 10.3 G)48) measured in aqueous solutions at ambient temperature are quite close to the isotropic HFCC value of the nitrogen with radical site (Aiso (N3) = 11.8 G) observed by von Sonntag et al.19 These agreements led von Sonntag et al.19 to the tentative assignment of this N-centered radical to the iminyl σ-radical (scheme 1). This previous work is in accord with our assignment of the spectrum in Figure 1(A), to the iminyl σ-radical (scheme 1). Indeed, the isotropic components of the HFCC values from our work are 13.3 G (N4) and 9.7 G (N3) (see Table 1) with an isotropic g-value of 2.0036. Considering the different media (homogeneous glassy solutions at low temperatures (our work) vs. aqueous solution at room temperature (von Sonntag et al.9, 19), the isotropic components of the HFCC values as well as the isotropic g-value from our work compare very well with those of von Sonntag et al.9, 19

Table 1.

Comparison of experimentally obtained HFCCs values of the iminyl-σ-radical and C(N4-H)• in Gauss (G) with those obtained by calculation using DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* method.

| Molecule | Radical | Atoms | HFCC (G) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory | Expa | |||||

| AIso |

AAniso xx yy zz |

A(total)a,b Axx Ayy Azz |

A(total)a,b Axx Ayy Azz |

|||

| 1-MeC | Iminyl-σ-radical | N4 atom | 11.6 (11.7d) |

26.2 −11.2 −15.1 |

37.2 0.4 −3.5 |

40 0 0 |

| N3 atom | 12.4 (12.3d) |

1.9 −0.6 −1.3 |

14.3 11.8 10.9 |

10.2 9.5 9.5 |

||

| H3 atom | 0.8 (0.8d) | 3.8 −1.2 −2.6 |

4.6 −0.4 −1.8 |

n.d. | ||

| 1-MeC | C(N4-H)•syn | N4 atom | 10.7 (10.8d) | 21.6 −10.7 −10.9 |

32.3 0.0 −0.2 |

28.0 0 0e |

| N3 atom | 4.3 (3.7d) | 8.1 −4.2 −3.9 |

12.4 0.1 0.4 |

10.5 0 0e |

||

| H4 atom | −17.6 | −3.8 16.9 −13.2 |

−20.8 −0.7 −30.8 |

|||

| C(N4-H)•anti | N4 atom | 10.5 | 21.44 −10.9 −10.5 |

31.94 −0.4 0 |

28.0 0 0e |

|

| N3 atom | 4.9 | 9.6 −4.9 −4.7 |

14.5 0 0.2 |

10.5 0 0e |

||

| H4 atom | 17.7 | 3.6 17.6 13.9 |

21.3 0.1 31.6 |

|||

Experiments give the magnitude but not the sign of the couplings. Estimated errors are of ±1 G for Azz, Axx, and Ayy. See supporting information Figure S1 for details.

A(total) = AIso + AAniso

n.d. = not detected

Ref. 19 reports only isotropic HFCC values which are shown in brackets.

The experimental spectrum (pink) in Figure 2(A) is analyzed to obtain the experimental values of Azz components of the nitrogen hyperfine couplings.

From the structural formula of the iminyl σ-radical (scheme 1), it is evident that the N3-atom is in a beta position to the p-orbital at the radical site on the N4-atom and should give an isotropic N-atom HFCC value as seen in the spectrum shown in Figure 1(A). We note here that there are reported nitrogen couplings that are β to the nitroxide nitrogen in spin trapped DNA-radicals,22 however, the nearly isotropic β-nitrogen HFCC in this iminyl σ-radical is the only β nitrogen coupling that is reported to date in a DNA-radical itself. This iminyl σ-radical assignment is aptly supported by DFT calculations (vide infra).

Formation of iminyl σ-radical in cidofovir, dCyd, and in 5'-dCMP

To investigate whether the cytosine iminyl σ-radical production is affected by the nature of the side chain at N1 of the cytosine base (scheme 1), we have employed matched samples of one-electron oxidized cidofovir, dCyd, and 5'-dCMP in homogeneous aqueous glassy solution (7.5 M LiCl/D2O (or H2O)) at pH 10 and above and have progressively annealed these samples up to ca. 160 to 165 K. These results are presented in Figures 1((B), for cidofovir) and 1((C), for dCyd) (see supporting information Figures S5 and S6 for cidofovir), and for 5'-dCMP (see supporting information Figure S7).

A simulated spectrum (black) using the same nitrogen HFCC values and g-values as employed for 1-Me-C iminyl σ-radical in Figure 1(A) is superimposed on the experimentally obtained spectrum (blue) in Figure 1(B) and both spectra match nicely. Hence, the spectra in Figure 1(B) are also assigned to the cidofovir iminyl σ-radical (scheme 1).

The experimentally recorded spectrum of one-electron oxidized dCyd (teal) is shown in Figure 1(C). The experimentally obtained iminyl σ-radical spectrum from 1-MeC (red, Figure 1(A)) has been superimposed on this spectrum for comparison. It is evident from both spectra shown in Figure 1(C) that spectrum obtained from the one-electron oxidized dCyd sample has the same hyperfine components as the iminyl σ-radical spectrum from 1-MeC but is overlapped with a broad underlying spectrum which we assign to dCyd C(N4-H)•, the untautomerized precursor of the iminyl σ-radical (See Figure 2(A) for the spectrum of C(N4-H)•, the π-radical for 1-MeC, and 2(B) for a similar case of overlap of the iminyl σ-radical over the broad π-radical). Hence, the spectrum of one-electron oxidized dCyd (teal) in Figure 1(C) is assigned to the dCyd iminyl σ-radical overlapped with dCyd (N4-H)• (scheme 1). Similar results were found employing the matched sample of 5'-dCMP; these results are presented in the supporting information Figure S7.

We note the N3-H proton would show only small HFCC values of ca. 2 G in the iminyl σ-radicals (see Table 1 and supporting information). Since this proton is exchanged in D2O system, the coupling is reduced by a factor of 6.514; thus, the N3-D does not contribute to the iminyl σ-radical spectrum.

pH dependence on the iminyl σ-radical formation

It is evident from Figure 1 that the 1-MeC iminyl σ-radical spectrum shows excellent resolution of the line components. Therefore, it is of interest to see the precursor radicals after one-electron oxidation. So, the effect of pH on the iminyl σ-radical formation has been investigated employing matched samples of 1-MeC in homogeneous 7.5 M LiCl/D2O glassy solutions with pH values of ca. 8, 9.5, and 11. The spectra of these samples are presented in Figure 2.

In Figure 2(A), the experimentally recorded (77 K) ESR spectrum (pink) of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC at pH (pD) ca. 8 in a homogeneous glassy 7.5 M LiCl/D2O solution is shown. Following our results in Figure 1, the one-electron oxidation of 1-MeC at pH ca. 8 was induced by Cl2•− attack after annealing at 160 K in the dark.

The experimentally recorded spectra obtained from matched samples of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC at pD ca. 9.5 (blue spectrum) and at ca. 11 (red spectrum) are shown in Figures 2(B) and (C). The spectrum of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC sample at pH ca. 11 was found to be identical to that shown in Figure 1(A). Therefore, the experimentally recorded spectrum (red) in Figure 1(A) is shown here as Figure 2(C). The simulated spectra in black Figure 2(A) and 2(C) are presented along with the experimentally recorded spectra. The experimentally recorded as well as the simulated spectra in Figure 2(C) are assigned to the same species – the iminyl σ radical (see Figure 1).

The blue spectrum in Figure 2(A) is best matched with a simulated spectrum that has been obtained employing two anisotropic 14N (nuclear spin = 1) HFCC values of (28.0, 0, 0) G and (10.5, 0, 0) G, a deuterium coupling (3.8, 0, 5.5) G, gxx, gyy, gzz (2.0019, 2.0047, 2.0047) along with an isotropic Gaussian line-width of 4.5 G. The simulation shows that the deuterium coupling only contributes to the broadening of the spectrum. The simulated spectrum in black is superimposed on the experimentally recorded spectrum in Figure 2(A) and both spectra match reasonably well. The radical species giving rise to Figure 2(A) is assigned to the neutral aminyl π-radical C(N4-H)• which is the precursor to the 1-MeC iminyl σ radical, scheme 1. Our DFT calculations show two anisotropic nitrogen HFCC values for C(N4-H)•syn which agree well with experiment (see pink spectrum in Figure 2(A), Table 1, and theory section).

Comparison of the experimentally recorded spectrum of one-electron oxidized 1-MeC sample (blue, pH ca. 9.5) in Figure 2(B) with that of the 1-MeC iminyl σ radical spectrum (red, pH ca. 11) in Figure 2(C) show that the blue spectrum contains line components of the iminyl σ radical spectrum (see dotted lines, especially at the left wings and at the center) and computer substraction shows that it accounts for approximately 30% of the overall intensity. Thus, we conclude that the spectrum 2(B) is a cohort of two radicals (C(N4-H)•syn ca. 70% (Figure 2(A) and iminyl σ radical ca. 30 % (Figure 2(C)).

These results, therefore, clearly show that C(N4-H)• is the precursor to the 1-MeC iminyl σ radical. Thus, both species C(N4-H)• and the iminyl σ-radical, which are in tautomeric equilibria (see scheme 1), are identified. In our system, we observe only ca. 30% conversion of C(N4-H)• to the iminyl σ-radical at pH ca. 9.5 after annealing the sample in the range 160 to 165 K for 15 min in the dark. Therefore, comparison of the experimental and theoretical work by von Sonntag et al.9, 19 for the CW ESR spectrum of SO4•−-induced one-electron oxidized 1-MeC in aqueous solution (pH ca. 7) with the CW ESR spectral studies of Cl2•−-induced one-electron oxidized 1-MeC in our homogeneous glassy solutions at low temperatures at higher pH (Figures 1 and 2) clearly show that the equilibrium between C(N4-H)• and the iminyl σ-radical at low temperature is too slow to be established without the base.

We note that our theoretical results predict that the iminyl σ-radicals do not undergo deprotonation at N3 (see theory).

Subsequent reaction of the iminyl σ-radical

Iminyl radicals are highly reactive and well-known for undergoing various types of reactions – such as, dimerization,48 addition to double and triple bonds,49 H-atom abstraction leading to DNA cleavage.50 von Sonntag proposed that the iminyl radical of 1-methylcytosine undergoes dimerization.9, 19 We also note that in the work employing DFT calculations in the gas phase and in the presence of water, the cytosine iminyl σ-radical has been shown to be the key intermediate in deamination of cytosine to uracil that is mediated by cytosine base π- cation radical or its deprotonated form, C(N4-H)•.51 Several alternative pathways have been suggested at room temperature in aqueous solutions. For example, C1'• formation and it’s diamagnetic product 2-deoxyribonolactone was reported by menadione-induced one-electron oxidation of dCyd due to type I photosensitization.22, 52 Also, in the same experiments 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosin-5-yl radical, was reported to be the predominant radical via hydration of π-cytosine radical cation.22, 52, 53

The line intensities of the iminyl σ-radical spectrum in 1-MeC decrease by ca. factor of 4 by progressive annealing from 160 K to ca. 170 K, (see supporting information Figure S4). We attribute this simple decay of line intensities to dimerization of the iminyl σ-radicals in 1-MeC.

Upon further annealing of matched cidofovir samples (0.6 to 9.8 mg/ml) to 170 or 175 K (see supporting information Figure S5), we find that the line components from the cidofovir iminyl σ-radical are decreased for samples with concentrations 0.6 and 2 mg/ml but not much for a sample with concentration 9.8 mg/ml. Simultaneously, a spectrum consisting of one anisotropic α-hydrogen HFCC ((10.0, 22.0, 35.0) G), one isotropic β-hydrogen HFCC (49.5 G) along with a g-value (2.0042, 2.0020, 2.0049) was found to develop without loss of signal intensity for cidofovir samples (concentrations 2 and 9.8 mg/ml) and not for the cidofovir sample 0.6 mg/ml. The g-value of this multiplet spectrum is in accord with those of the C-centered radicals near heteroatoms.2 – 4, 7, 8, 35 This concentration dependent formation of the C-centered radical ruled out a cidofovir iminyl σ-radical-induced deprotonation reaction similar to our recent findings of C3'• formation in gemcitabine35 or by intramolecular H-atom abstraction by the iminyl σ-radical either from the -CH2-OH moiety or from the N1-CH2- moiety on the cidofovir side chain (see scheme 1). However, the concentration dependent C-centered radical production points to a bimolecular addition of the iminyl σ-radical to the C5=C6 double bond of an unreacted proximate cidofovir molecule.

Influence of the solvent (D2O vs. H2O) on formation of the iminyl σ-radical in 1-MeC and cidofovir

Employing 1-MeC as well as cidofovir samples in H2O instead of a D2O glass (7.5 M LiCl/H2O, pH ca. 10), ESR studies on formation of the iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized 1-MeC and cidofovir were carried out to observe the effect of couplings from exchangeable proton sites. These results are presented in supporting information Figures S2, S3, and S6. The results in Figure S3 are compared with those obtained using a matched 1-MeC sample in D2O glass. It is evident from Figures 1, S2(D), S3(D), and S6(C) that these spectra are due to the iminyl σ-radical. Owing to the relatively softer nature of an H2O glass than a D2O glass, progressive warming of the 1-MeC and cidofovir samples in H2O glass to 155 K result in the complete conversion of C(N4-H)• to the iminyl σ-radical (Figure 1) as found in D2O glasses at 165 K.

It is evident from the spectral simulations for the iminyl σ-radical in Figure 1 and in Figures S2(D), S3(D), and S6(C) that change of solvent (D2O vs. H2O) causes observable line broadening (5 G in D2O vs. 7.5 G in H2O) and affects lineshape (mixed (Lorentzian/Gaussian =1) for D2O vs. Gaussian in H2O); but, most importantly, the N-atom hyperfine couplings ((40.0, 0, 0) G and (10.2, 9.5, 9.5) G) and the g-values (gxx, gyy, gzz (2.0023, 2.0043, 2.0043)) remain unaltered. For the 1-MeC iminyl σ-radical, the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* predicted HFCC value of ca. 3 G for the exchangeable N3-H proton (Table 1) is less than the linewidth of 7.5 G and hence cannot be observed in the broad ESR spectrum (Figures S2 and S3). However, the exchangeable N3-H proton HFCC should contribute to the observed line broadening. Moreover, Figures S3(D) and S6(C) show the presence of outermost weak line components (outermost lines at ca. 127 G). These small components are from an unidentified species in low intensity and are not included in the simulation.

We conclude that the iminyl σ-radical is produced in H2O systems as in D2O with only line broadening of the ESR spectra. Thus, the change of solvent does not affect the reactions leading to formation of iminyl σ-radical shown in scheme 1.

Theoretical studies

Cytosine iminyl σ-radical in 1-MeC

In this DFT study, we have considered 1-MeC•+ (scheme 1) along with three different tautomers of C(N4-H)• (scheme 1) : (i) deprotonation of 1-MeC•+ at either the syn or anti sites of the >C=O group at C2 with respect to the N4-H atom (scheme 1) leading to the formation of C(N4-H)•, and (ii) iminyl-σ-radical tautomer of C(N4-H)• (scheme 1). The geometries of all these radicals were fully optimized by employing B3LYP/6-31G* method in the gas phase (see supporting information). The relative stabilities of the three different tautomers of C(N4-H)•, C(N4-H)•anti, C(N4-H)•syn, and iminyl-σ-radical were 0.00, −5.50, and −9.01 kcal/mol, respectively (scheme 1). These calculations clearly predict that the iminyl-σ-radical is the most stable radical species when compared to C(N4-H)•syn and C(N4-H)•anti. The stability (3.5 kcal/mol) of the iminyl-σ-radical in comparison to C(N4-H)•syn is in good agreement with that (2.5 kcal/mol) calculated by von Sonntag et al. by employing UB3LYP/6-31G(d)/Onsagar SCRF method19. The experimentally determined HFCC values (see Figure 2) of C(N4-H)• match very well with the predicted HFCC values of C(N4-H)•syn.

It is evident from Table 1 that our calculated isotropic HFCC values of 1-MeC iminyl-σ-radical are in very good agreement with those calculated by von Sonntag et al.19 The combination of our ESR and theoretical studies (see also supporting information) clearly point out that:

the theoretically calculated HFCC values of 1-MeC iminyl-σ-radical are in very good agreement with its experimentally observed HFCC values (Table 1) and, this agreement justifies the radical assignment of the spectra shown in Figure 1. Furthermore, experimental values of Azz components of the nitrogen hyperfine couplings owing to C(N4-H)• are in good agreement with the theoretically calculated values.

deprotonation from the N4 amine group in 1-MeC•+ at the syn site of the >C=O group at C2 with respect to the N4-H atom should aid the tautomeric formation of the iminyl-σ-radical. It is evident from the relative stabilities of C(N4-H)•syn and C(N4-H)•anti (see scheme 1 and supporting information).

Our theoretical results show that iminyl σ-radical should not undergo deprotonation at N3 as the N3-deprotonated iminyl σ-radical is destabilized in solution by over 30 kcal/mol (ΔG= −32 kcal/mol) over its conjugate acid (or the N3-protonated form) (see supporting information).

as expected for a neutral π-radical such as C(N4-H)•, we find two axially symmetric anisotropic nitrogen HFCC values; whereas, the iminyl σ-radical shows one anisotropic and one near isotropic nitrogen HFCC values (see Table 1, supporting information Figure S11).

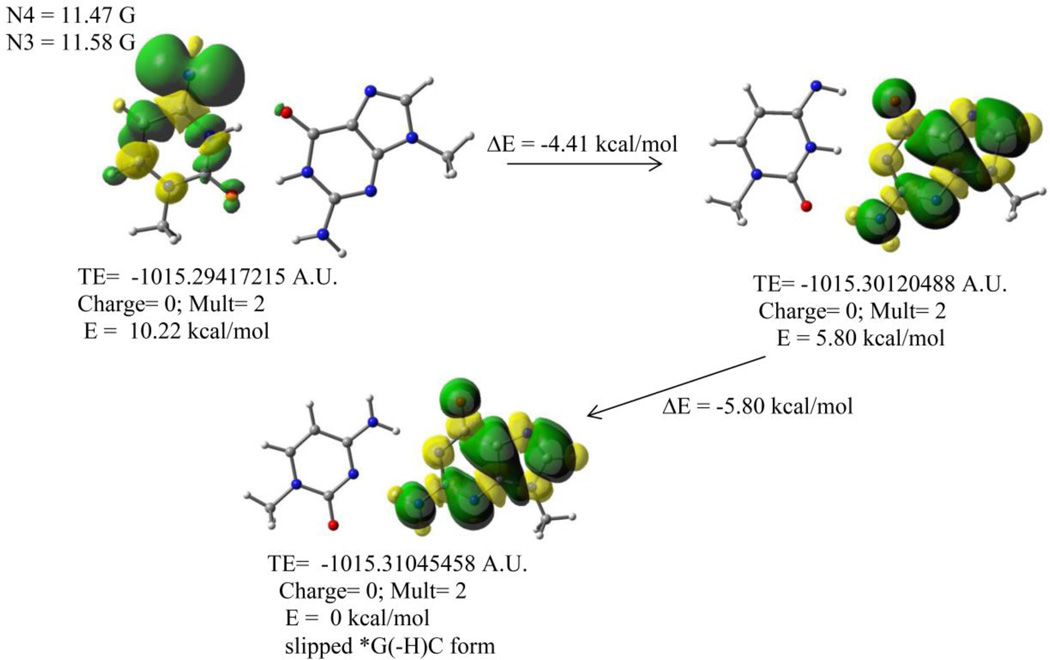

Role of cytosine iminyl σ-radical in the formation of guanyl radical in DNA

Photolytically generated aminyl and iminyl radicals from arylhydrazones show DNA cleaving activity in aqueous solution (pH ca. 7) at ambient temperature.49 In addition, experimental and theoretical work by von Sonntag et al.9, 19 for the CW ESR spectrum of SO4•−-induced one-electron oxidized 1-MeC along with our results at low temperature (this work) clearly show that the C(N4-H)• tautomerizes to the iminyl σ-radical in aqueous solution (pH ca. 7) at room temperature. Therefore, it would be of interest to investigate the role of cytosine iminyl σ-radical in the G:C base pair. Based on pulse radiolysis studies at ambient temperature in aqueous solution (pH ca. 7) of one-electron oxidized calf thymus DNA, Anderson et al. has proposed cytosine iminyl σ-radical “gated” neutral guanyl radical (G(N1-H)•:C) formation (see scheme 1 in Ref. 21). In lieu of this, we have employed ωb97x/6-31++G(d) method for geometry optimization to study the reaction energies along with spin density distribution plots for localization of the radical site of cytosine iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized G:C base pair. We have employed the integral equation formalism polarized continuum model (IEF-PCM) as implemented in Gaussian 09 to treat the effect of full solvent (see “materials and methods”).

Each radical species shown in the scheme by Anderson et al.21, is designated as (A), (B), (C), and (D) (see supporting information Figure S9). The reaction energy for the formation of radical (B) from radical (A) in the scheme proposed by Anderson et al.21 is found to be endothermic (31.6 kcal/mol). The spin density distribution plots in each of the radicals (A) to (D) show that the unpaired spin (electron) is localized only on the guanine base in the one-electron oxidized G:C base pair. Thus, these results clearly show that the mechanism proposed by Anderson et al.21 is not energetically feasible. To resolve this issue, we have extensively searched for the most feasible reaction path that involves cytosine iminyl σ-radical “gated” (G(N1-H)•:C) formation as a modification of the mechanism proposed by Anderson et al. and have shown that in Figure 3 (see also supporting information Figure S10). The calculated reaction energy in each step is exothermic. The spin density distribution plots in radical (B) (the starting radical in Figure 3 and radical (B) in supporting information Figure S10) clearly show the cytosine iminyl σ-radical as an intermediate. The cytosine iminyl σ-radical “gated” (G(N1-H)•:C) is in the “slipped” form34, 54, 55 and is ca. 10 kcal/mol more stable than the unslipped one-electron oxidized G:C base pair involving authentic cytosine iminyl σ-radical (compare the nitrogen HFCC values with those in Table 1).

Figure 3.

Proposed role of the cytosine iminyl σ-radical to produce neutral guanyl radical (G(N1-H)•:C (or, *G(-H)C)) via proton coupled electron transfer in the one-electron oxidized 9-Me-G:1-Me-C (Me group at N9 in G and at N1 in C mimic sugar moieties). The calculations were performed employing ωb97x/PCM/6-31++G(d) method for geometry optimization and spin density distribution plots (also see supporting information Figure S10). TE = total energy in atomic unit (A.U.). The HFCC values of N3 and N4 were shown for the 1-Me-C iminyl σ-radical (see left uppermost panel) in the one-electron oxidized 9-Me-G:1-Me-C and these values agree with those observed in the monomer (see Table 1).

Conclusion

Our work has the following salient findings:

The cytosine π-cation radical is shown to most favorably deprotonate in its ground state from the N4 exocyclic amine at the syn site of the >C=O group at C2 with respect to the N4-H atom by producing the aminyl π-radical (C(N4-H)•). C(N4-H)• tautomerizes to form the iminyl σ-radical. The unusual nature of the sigma radical is that it is localized to an in plane pure p-orbital of the exocyclic amine and shows large anisotropic alpha nitrogen coupling to N4 (Azz = 40 G) and an isotropic β- nitrogen coupling of 9.7 G to the cytosine ring nitrogen at N3. The nature of this species was earlier proposed by von Sonntag et al.19 and our work establishes this in an unequivocal fashion.

Under similar experimental conditions, deprotonation and subsequent tautomerization of the cytosine π-cation radical (scheme 1, this work) prevails over the nucleophilic addition of hydroxyl anion (or water) as found for the thymine π-cation radical or its deprotonated form22. Thus, these results show that thymine and cytosine π-cation radical would undergo different reactions under similar conditions. The tautomerization of C(N4-H)• to iminyl σ-radical has thus been observed in homogeneous glassy solution (this work) and in aqueous solution at ambient temperature by von Sonntag et al.19 However, there are experimental observations of hydration of C(N4-H)• in aqueous solution at ambient temperature prevailing over its tautomerization to iminyl σ-radical; for example, 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrocytosin-5-yl radical, has been observed to be the predominant radical via hydration of (N4-H)• produced in a photosensitized reaction.22, 52, 53

Our theoretical calculations predict that the cytosine iminyl σ-radical could be formed in dsDNA by the radiation-induced ionization–deprotonation process on cytosine that is only 10 kcal/mol above the lowest energy G:C radical form (slipped form of guanine N1-deprotonated G:C cation radical34, 54, 55). This is similar to the proposal of Anderson and coworkers21 who first suggested the cytosine iminyl σ-radical as an intermediate in DNA one-electron oxidation; however, our theoretical calculations provide an energy pathway that is lower than that is obtained by the suggested proposal of Anderson et al.21

Our ESR studies suggest that several reactions of iminyl σ-radicals in cytosine monomers may occur, such as, carbon-centered radical formation on the N1 side chain by deprotonation or by dimerization of the iminyl σ-radical itself. In addition, our results (Figures 1, 2) at low temperature in homogeneous glassy solutions along with the studies of von Sonntag et al.9, 19 on SO4•−-induced one-electron oxidized 1-MeC in aqueous solution (pH ca. 7) point out that the cytosine π- cation radical deprotonates in the ground state from the exocyclic amine of the cytosine base (scheme 1 and Figure S8).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01CA045424 for support. We also thank the reviewers for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available:

Supporting information contains the following: (i) Estimated uncertainties (errors) in HFCC values, (ii) Formation of iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized 1-Me-C in 7.5 M LiCl/H2O. (iii) Formation of iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized 1-Me-C in D2O and in H2O. (iv) Formation of iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized 1-Me-C in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O and its subsequent reaction via annealing at 170 K. (v) Formation of iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized cidofovir in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O and its subsequent reaction via annealing at 170 K at different concentrations of cidofovir. (vi) Formation of iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized cidofovir and in 1-MeC in 7.5 M LiCl/H2O. (vii) Formation of iminyl σ-radical in one-electron oxidized 1-MeC, cidofovir, dCyd, and 5'-dCMP in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O. (viii) Comparison of ESR spectrum of iminyl σ-radical formed in 1-MeC with that of C1'•. (ix) Proposed scheme of guanyl radical (G(N1-H)•:C) formation in the one-electron oxidized 9-Me-G:1-Me-C (Me group at N9 in G and at N1 in C mimic sugar moieties). (x) Proposed role of the cytosine iminyl σ-radical to produce guanyl radical via proton coupled electron transfer in the one-electron oxidized 9-Me-G:1-Me-C (Me group at N9 in G and at N1 in C mimic sugar moieties). (xi) Spin density distribution plots obtained employing B3LYP/ 6-31G* method in B3LYP/ 6-31G* geometry optimized structures of 1-MeC π cation radical, C(N4-H)•anti, C(N4-H)•syn, and of 1-MeC iminyl σ radical (xii) B3LYP/6-31G* optimized structures of various radicals considered in this work and their isotropic and anisotropic HFCC values. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. The Role of Charge and Spin Migration in DNA Radiation Damage. In: Chakraborty T, editor. Charge Migration in DNA: Physics, Chemistry and Biology Perspectives. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp. 139–175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Close DM. From the Primary Radiation Induced Radicals in DNA Constituents to Strand Breaks: Low Temperature EPR/ENDOR studies. In: Shukla MK, Leszczynski J, editors. Radiation-induced Molecular Phenomena in Nucleic Acids: A Comprehensive Theoretical and Experimental Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 493–529. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernhard WA. Radical Reaction Pathways Initiated by Direct Energy Deposition in DNA by Ionizing Radiation. In: Greenberg MM, editor. Radical and Radical Ion Reactivity in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009. pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagstuen E, Hole EO. Radiation Produced Radicals. In: Brustolon, Giamello, editors. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009. pp. 325–381. (2009) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. Mechanism of Radiation Induced DNA Damage: Direct Effects. In: Rao BSM, Wishart J, editors. Recent Trends in Radiation Chemistry. Singapore, New Jersey, London: World Scientific Publishing Co.; 2010. pp. 509–542. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. Physicochemical Mechanisms of Radiation Induced DNA Damage. In: Hatano Y, Katsumura Y, Mozumder A, editors. Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter - Recent Advances, Applications, and Interfaces. Boca Raton, London, New York: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adhikary A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Electron Spin Resonance of Radicals in Irradiated DNA. In: Lund A, Shiotani, editors. Applications of EPR in radiation research. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2014. pp. 299–352. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adhikary A, Becker D, Palmer BJ, Heizer AN, Sevilla MD. Direct Formation of The C5′-radical in The Sugar-phosphate Backbone of DNA By High Energy Radiation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:5900–5906. doi: 10.1021/jp3023919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Sonntag C. Free-radical-induced DNA Damage and Its Repair. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 213–482. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Theory and ESR Spectral Studies of DNA-radicals. In: Chatgilialoglu C, Struder A, editors. Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 1371–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steenken S. Purine Bases, Nucleosides and Nucleotides: Aqueous Solution Redox Chemistry and Transformation Reactions of Their Radical Cations and e− and OH-adducts. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:503–520. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenken S. Electron-transfer-induced Acidity/Basicity and Reactivity Changes of Purine and Pyrimidine Bases. Consequences of Redox Processes for DNA Base Pairs. Free Radical Res. Commun. 1992;16:349–379. doi: 10.3109/10715769209049187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steenken S. Electron Transfer in DNA? Competition by Ultra-fast Proton Transfer? Biol. Chem. 1997;378:1293–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Z, Sevilla MD. Studies of Excess Electron and Hole Transfers. In: Schuster GB, editor. Long Range Charge Transfer in DNA II; Topics In Current Chemistry. Vol. 237. Springer; 2004. pp. 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A, Sevilla MD. π- vs. σ-Radical States of One-electron-oxidized DNA/RNA Bases: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:11623–11632. doi: 10.1021/jp407897n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bešić E, Sanković K, Gomzi V, Herak JN. Sigma Radicals in Gamma-irradiated Single Crystals of 2-Thiothymine. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:2723–2725. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevilla MD, Swarts S. Electron Spin Resonance Study of Radicals Produced by One-electron Loss From 6-Azauraci1, 6-Azathymine, and 6-Azacytosine. Evidence for Both σ and π Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1982;86:1751–1755. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Neill P, Davies SE. Pulse Radiolytic Study of the Interaction of SO4•− With Deoxynucleosides. Possible Implications for Direct Energy Deposition. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1987;52:577–587. doi: 10.1080/09553008714552071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naumov S, Hildenbrand K, von Sonntag C. Tautomers of the N-centered Radical Generated by Reaction of SO4•− With N1-substituted Cytosines in Aqueous Solution. Calculation of Isotropic Hyperfine Coupling Constants by a Density Functional Method. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2001;2:1648–1653. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geimer J, Hildenbrand K, Naumov S, Beckert D. Radicals Formed by Electron Transfer From Cytosine and 1-Methylcytosine to the Triplet State of Anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonic Acid. A Fourier-transform EPR Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000;2:4199–4206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson RF, Shinde SS, Maroz A. Cytosine-gated Hole Creation and Transfer in DNA in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15966–15967. doi: 10.1021/ja0658416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishna CM, Decarroz C, Wagner JR, Cadet J, Riesz P. Menadione Sensitized Photooxidation of Nucleic Acid and Protein Constituents. An ESR and Spin-trapping Study. Photochem. Photobiol. 1987;46:175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Heizer AN, Palmer BJ, Pottiboyina V, Liang Y, Wnuk SF, Sevilla MD. Hydroxyl Ion Addition to One-electron Oxidized Thymine: Unimolecular Interconversion of C5 to C6 OH-adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3121–3135. doi: 10.1021/ja310650n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khanduri D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. Highly Oxidizing Excited States of One-electron Oxidized Guanine in DNA: Wavelength and pH Dependence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4527–4537. doi: 10.1021/ja110499a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Palmer BJ, Todd AD, Heizer AN, Sevilla MD. Adhikary A, Cadet J, O'Neill P, editors. Reactions of 5-Methylcytosine Cation Radicals in DNA and Model Systems: Thermal Deprotonation From the 5-Methyl group vs. Excited State Deprotonation From Sugar. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2014;90(Clemens von Sonntag Memorial issue):433–445. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.884293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Palmer BJ, Todd AD, Sevilla MD. Formation of S-Cl Phosphorothioate Adduct Radicals in dsDNA-S-oligomers: Hole Transfer to Guanine vs. Disulfide Anion Radical Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12827–12838. doi: 10.1021/ja406121x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adhikary A, Malkhasian AYS, Collins S, Koppen J, Becker D, Sevilla MD. UVA-visible Photo-excitation of Guanine radical cations Produces Sugar Radicals in DNA and Model Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5553–5564. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adhikary A, Collins S, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. Sugar Radicals Formed by Photo-excitation of Guanine Cation Radical in Oligonucleotides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7415–7421. doi: 10.1021/jp071107c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. The Guanine Cation Radical: Investigation of Deprotonation States by ESR and DFT. J. Phys Chem. B. 2006;110:24170–24180. doi: 10.1021/jp064361y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khanduri D, Collins S, Kumar A, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. Formation of Sugar Radicals in RNA Model Systems and Oligomers via Excitation of Guanine Cation Radical. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:2168–2178. doi: 10.1021/jp077429y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. The Effect of Base Stacking on The Acid-base Properties of The Adenine Cation Radical [A•+] in Solution: ESR and DFT Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10282–10292. doi: 10.1021/ja802122s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Kumar A, Sevilla MD. Photo-excitation of Adenine cation radical [A•+] in The Near UV-vis Region Produces Sugar Radicals in Adenosine and in Its Nucleotides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:15844–15855. doi: 10.1021/jp808139e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Pottiboyina V, Rice CT, Sevilla MD. Formation of Aminyl Radicals on Electron Attachment to AZT: Abstraction From the Sugar Phosphate Backbone vs. One-electron Oxidation of Guanine. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:9289–9299. doi: 10.1021/jp103403p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Munafo SA, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. Prototropic Equilibria in DNA Containing One-electron Oxidized GC: Intra-duplex vs. Duplex to Solvent Deprotonation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12:5353–5368. doi: 10.1039/b925496j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Rayala R, Hindi RM, Adhikary A, Wnuk SF, Sevilla MD. One-electron Oxidation of Gemcitabine and Analogs: Mechanism of Formation of C3′ and C2′ Sugar Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15646–15653. doi: 10.1021/ja5083156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, et al. Gaussian 09. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raiti MJ, Sevilla MD. Density Functional Theory Investigation of The Electronic Structure and Spin Density Distribution in Peroxyl Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1999;103:1619–1626. [Google Scholar]

- 38.GaussView. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomasi J, Mennucci B, Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999–3093. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chai J-D, Head-Gordon M. Systematic Optimization of Long-range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:084106. doi: 10.1063/1.2834918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chai J-D, Head-Gordon M. Long-range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals With Damped Atom–atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008;10:6615–6620. doi: 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar A, Sevilla MD. Proton Transfer Induced SOMO-to-HOMO Level Switching in One-electron Oxidized A-T and G-C Base Pairs: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:5453–5458. doi: 10.1021/jp5028004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Clercq E. The Acyclic Nucleoside Phosphonates From Inception to Clinical Use: Historical Perspective. Antiviral Res. 2007;75:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snoeck R, Sakuma T, De Clercq E, Rosenberg I, Holy A. (S)-1-(3-Hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine, A Potent and Selective Inhibitor of Human Cytomegalovirus Replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1839–1844. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.12.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baik M-H, Silverman JS, Yang IV, Ropp PA, Szalai VS, Thorp HH. Using Density Functional Theory to Design DNA Base Analogues With Low Oxidation Potentials. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:6437–6444. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Close DM. Calculated pKa’s of The DNA Base Radical Ions. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;117:473–480. doi: 10.1021/jp310049b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kolano C, Bucher G, Wenk HH, Jäger M, Schade O, Sander W. Photochemistry of 9-Fluorenone Oxime Phenylglyoxylate: A Combined TRIR, TREPR and ab initio Study. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2004;17:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griller D, Mendenhall GD, Van Hoof W, Ingold KU. Kinetic Applications of Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. XV. Iminyl Radicals’. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:6068–6070. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portela-Cubillo F, Alonso-Ruiz R, Sampedro D, Walton JC. 5-Exo-cyclizations of Pentenyliminyl Radicals: Inversion of The Gem-dimethyl Effect. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2009;113:10005–10012. doi: 10.1021/jp9047902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwu JR, Lin CC, Chuang SH, King KY, Su T-R, Tsay S-C. Aminyl and Iminyl Radicals From Arylhydrazones in The Photo-induced DNA Cleavage. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:2509–2515. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labet V, Grand A, Cadet J, Eriksson LA. Deamination of The Radical Cation of The Base Moiety of 2′-Deoxycytidine: A Theoretical Study. Chem Phys Chem. 2008;9:1195–1203. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Decarroz C, Wagner JR, van Lier JE, Krishna CM, Riesz P, Cadet J. Sensitized Photo-oxidation of Thymidine by 2-Methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone. Characterization of The Stable Photoproducts. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1986;50:491–505. doi: 10.1080/09553008614550901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wagner JR, Cadet J. Oxidation Reactions of Cytosine DNA Components by Hydroxyl Radical and One-electron Oxidants in Aerated Aqueous Solutions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:564–571. doi: 10.1021/ar9002637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reynisson J, Steenken S. DNA-base Radicals. Their Base Pairing Abilities As Calculated by DFT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002;4:5346–5352. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bera PP, Schaefer HF., III (G-H)*-C and G-(C-H)* Radicals Derived From The Guanine.Cytosine Base Pair Cause DNA Subunit Lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:6698–6703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408644102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.