Abstract

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) that includes only 150 patients described to date meeting the latest World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and the recently reported CSF3R mutations. The diagnosis is based on morphological criteria of granulocytic cells and the exclusion of genetic drivers that are known to occur in others MPNs, such as BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, or FGFR1 rearrangements. However, this scenario changed with the identification of oncogenic mutations in the CSF3R gene in approximately 83% of WHO-defined and no monoclonal gammopathy-associated CNL patients. CSF3R T618I is a highly specific molecular marker for CNL that is sensitive to inhibition in vitro and in vivo by currently approved protein kinase inhibitors. In addition to CSF3R mutations, other genetic alterations have been found, notably mutations in SETBP1, which may be used as prognostic markers to guide therapeutic decisions. These findings will help to understand the pathogenesis of CNL and greatly impact the clinical management of this disease. In this review, we discuss the new genetic alterations recently found in CNL and the clinical perspectives in its diagnosis and treatment. Fortunately, since the diagnosis of CNL is not based on exclusion anymore, the molecular characterization of the CSF3R gene must be included in the WHO criteria for CNL diagnosis.

Keywords: CSF3R, SETBP1, CNL, neutrophilic, WHO, PTK inhibitors

Current diagnosis criteria and treatment for chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL)

CNL is an uncommon myeloid malignancy characterized by a high number of mature neutrophils in the peripheral blood (PB), a hyperplasic bone marrow (BM), and hepatosplenomegaly.1 Applying the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for CNL, the diagnosis could be confirmed in only 51% of the clinically suspected patients with CNL. For the “true” CNL cases, the median age was 65 years (26–83 years) at diagnosis of which 67% were male.2

The disease course of CNL is variable, but acceleration is typically characterized by refractory neutrophilia, worsening organomegaly, and blastic transformation. Median time to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) transformation is 21 months (3–94 months) and median survival is 23.5 months (1–106 months). The most frequent causes of death are intracranial hemorrhage, progressive disease/blastic transformation, and regimen-related toxicity from induction chemotherapy or transplantation.1,3

Clinical presentation

No specific symptom is observed at diagnosis presentation, and leukocytosis is detected incidentally in routine laboratory tests. The most frequent symptom is hepatosplenomegaly and some patients present with fatigue, weight loss, and bruise. Lymphadenopathy is uncommon at CNL presentation.1

Laboratory findings

The laboratory features of CNL include persistent neutrophilic leukocytosis with minimal left-shift, often characterized by toxic granulation and Döhle bodies, and elevated leukocyte alkaline phosphatase (LAP) and vitamin B12 levels.1,3–5

According to the 2008 WHO diagnostic criteria for CNL, the PB leukocytosis is ≥25×109/L (median 57×109/L, but as high as 138×109/L);2 where more than 80% of leukocytes are segmented neutrophils/band forms; <10% are immature granulocytes (promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes); and <1% myeloblasts.5 Granulocytic dysplasia is not present, and there is no monocytosis, eosinophilia, or basophilia. The hemoglobin levels are low (more or less 11.0 g/dL) and the platelet numbers are normal but often they decrease in the advanced stages of the disease.1

BM morphology

BM aspirates and biopsies show a myeloid hyperplasia (>90% cellularity) where myeloblasts represent less than 5% of the cells. Erythro and megakaryopoiesis are typically normal, and dyspoiesis are not present in any cell lineage. Reticulin fibrosis is not significantly increased.

CNL co-occurs with monoclonal gammopathy (MG) of undetermined significance in approximately 33% of the cases.2 This phenomenon has been reported in the literature with this subset of 12 patients presenting a MG associated with lambda light chain excess.6,7 However, it remains unclear whether the neutrophilic leukocytosis is a leukemoid response to the underlying MG, or if the presence of the two diseases represents a real entity.8 In cases where the BM shows a plasma cell dyscrasia, it is important to prove the neutrophilic clonality by cytogenetic and/or molecular tests.6

Molecular cytogenetics and clonality

Molecular cytogenetics should be negative for the well-defined markers of other neoplasms such as the Philadelphia chromosome and the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene (characteristic of chronic myeloid leukemia – CML); and rearrangements in PDGFRA/B or FGFR1 (characteristic of eosinophilic leukemia). Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) mutations are not specific for any myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) but can provide evidence that the proliferation is clonal.5 Although clonality has been demonstrated in CNL,9,10 the majority of patients exhibit normal cytogenetics.1,3,4 In CNL, trisomy 8 and del(20q) are the most common nonspecific chromosomal abnormalities observed at diagnosis or at the time of progressive disease.

Differential diagnosis

Exclusionary criteria include no evidence of a reactive neutrophilia (inflammatory, infectious, or malignant disease) or other MPNs, such as primary myelofibrosis (PMF), polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), and atypical CML (aCML).5

PV diagnosis requires hemoglobin levels >18.5 g/dL in men and >16.5 g/dL in women or the presence of JAK2 V617F or JAK2 exon 12 mutation. In the case of ET, a platelet count >450×109/L is necessary, and we observe megakaryocyte proliferation with large and mature morphology and demonstration of JAK2 V617F or other clonal marker or no evidence of reactive thrombocytosis. In the case of PMF, megakaryocyte proliferation and atypia are observed, accompanied by either reticulin and/or collagen fibrosis; or demonstration of JAK2 V617F or other clonal marker or no evidence of reactive BM fibrosis. In CMML, we observe a persistent (>3 months) PB monocytosis (>1×109/L), no BCR-ABL1, no PDGFRA/B mutations, <20% blast or promonocytes in BM or PB, and dysplasia or clonal cytogenetic or molecular abnormality. Finally, for aCML, PB leukocytosis >13×109/L, increased neutrophils/precursors with dysgranulopoiesis, >10% immature granulocytes, <20% PB myeloblasts, no BCR-ABL1, no PDGFRA/B mutations, <2% PB basophilia, no monocytosis and <10% PB monocytes; and BM hypercellular with increased granulocyte proliferation and granulocytic dysplasia in erythroid or megakaryocytic lineages; <20% myeloblasts are observed.5

In particular, in cases of plasma cell dyscrasia, it is important to prove the neutrophilic clonality by cytogenetic and/or molecular tests. The current diagnostic criteria for CNL (WHO 2008) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

2008 WHO diagnostic criteria for CNL

| • Leukocytosis (WBC ≥25×109/L) Segmented neuthrophils/band >80% Immature granulocytes <10% Myeloblasts <1% |

| • Hypercellular BM Neutrophilic granulocytes increased in number and percentage Myeloblasts <5% Neutrophilic maturation pattern normal Megakaryocytes normal or left shifted |

| • Hepatosplenomegaly |

| • No cause for neutrophilia or, if so, clonality No infectious/inflammatory process No underlying tumor |

| • No BCR-ABL1 |

| • No PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1 rearrangements |

| • No evidence of PV, ET, or PMF |

| • No evidence of MDS or MDS/MPN No granulocytic dysplasia No myelodysplastic changes Monocytes <1×109/L |

Notes: Diagnosis requires leukocytosis (≥25×109/L), >80% neutrophils, <10% immature granulocytes, and 1% myeloblasts. No dysplasia, monocytosis, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGRF1 rearrangements, and no underlying process that can cause neutrophilia.

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; CNL, chronic neutrophilic leukemia; WBC, white blood cells; BM, bone marrow; PV, polycythemia vera; ET, essential thrombocythemia; PMF, primary myelofibrosis; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Treatment and stem-cell transplantation (SCT)

No standard of care exists for CNL. Therapy has primarily consisted of hydroxyurea or other oral chemotherapeutics, as well as interferon-alpha.1,3,4,11–15 These agents can elicit an improvement in blood counts, but exhibit no proven disease-modifying benefit. Although splenic irradiation and splenectomy may provide transient palliation of symptomatic splenomegaly, the latter has been associated with the worsening of neutrophilic leukocytosis in CNL. The limited experience with induction-type chemotherapy for blastic transformation is generally poor, with death related to resistant disease or regimen-related toxicities.

As CNL frequently progresses to blast crises and to be refractory to therapy, allogeneic hematopoietic SCT represents the only possibility to cure these patients. Revisiting SCT in CNL patients, it is observed that the 71% of the patients who received the transplant at the chronic phase have an ongoing remission of more than 7 months, in contrast with those who received it at the accelerated phase and died after the procedure.3,16–18 To summarize, SCT may result in favorable long-term outcomes in selected patients, particularly when undertaken in the chronic phase of disease.1,3,4,11,13

Genetic alterations in CNL

As stated above, due to the lack of either specific or prognostic molecular markers, the diagnosis of CNL has been considered of exclusion. However, in 2013, a disease-defining mutation in CSF3R and a potentially prognostic mutation in set binding protein 1 (SETBP1) were found.2,19,20 Since then, the scientific community has considerably progressed in the molecular pathogenesis of CNL and an additional genetic alteration has been reported.21 In the following sections, we will revisit the main molecular alterations in CNL.

CSF3R mutations

Mutations in CSF3R have been recently defined as the common genetic event in patients with CNL by Maxson et al,19 becoming a potentially useful biomarker for diagnosing and therapy target.2,22 CSF3R encodes the transmembrane receptor for the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF; CSF3), which provides the proliferative and survival signal for granulocytes and also contributes to their differentiation and function.23–25

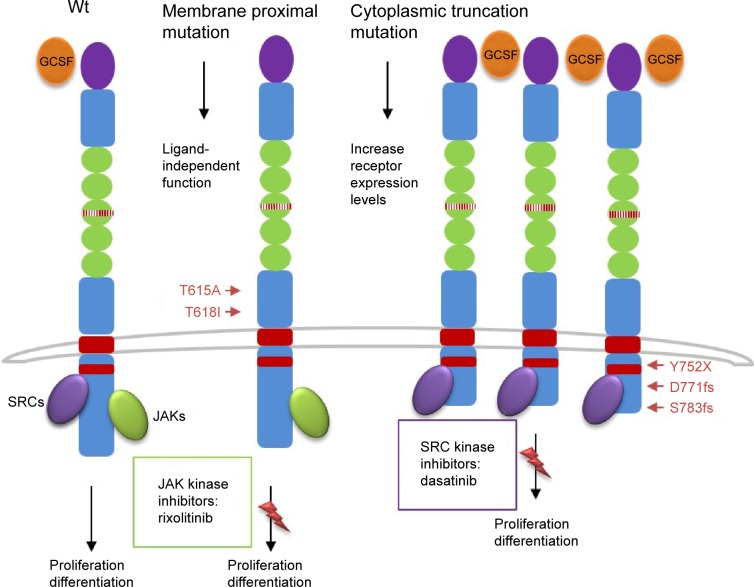

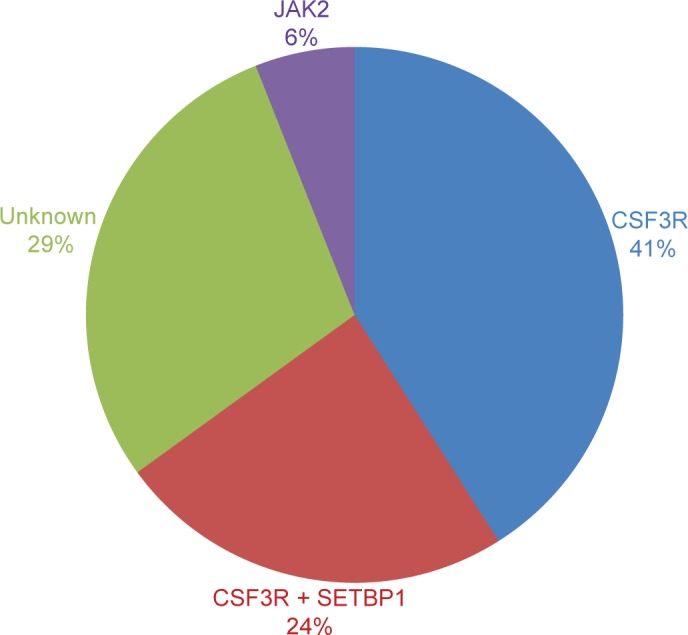

These mutations were present in approximately 83% of patients with WHO-defined/no MG-associated CNL (Figure 1) and fall into two classes: nonsense or frameshift mutations (D771fs, S783fs, and Y752X) that lead to the premature truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor (same as the secondary CSF3R mutation in severe congenital neutropenia [SCN]); and point mutations in the extracellular domain of CSF3R (T615A and T618I). The most common CSF3R alteration in CNL is the membrane proximal mutation T618I. CSF3R is known to signal downstream through both Janus kinase (JAK) and SRC tyrosine kinase pathways, and the two classes of CSF3R mutations exhibit different downstream signaling and kinase inhibitor sensitivities. CSF3R truncation mutations operate predominantly through SRC kinases, and exhibit drug sensitivity to SRC kinase inhibitors, such as dasatinib. In contrast, CSF3R membrane proximal mutations strongly activate the JAK/STAT pathways and are sensitive to JAK kinase inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib in vitro (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CNL mutations frequencies.

Notes: Percentages of CSF3R, SETBP1, and JAK2 V617F mutations in 18 CNL WHO-defined patients are shown. Six out of 18 were MGUS/lymphoma-associated, and none had CSF3R or SETBP1 mutations and only one presented JAK2 V617F.

Abbreviations: CNL, chronic neutrophilic leukemia; WHO, World Health Organization; SETBP1, set binding protein 1; JAK2, Janus kinase 2.

CSF3R mutations have been first described in patients with SCN, which can evolve into AML if a secondary CSF3R mutation develops at the time of transformation.26–29 These new nonsense or frameshift mutations truncate the cytoplasmic tail of CSF3R, impair its internalization, and alter its interactions with proteins such as SOCS family members.30–32 These structural and functional alterations are thought to perturb the ability of CSF3R to regulate granulocyte differentiation and to increase granulocytic proliferative capacity.33–35

SETBP1 mutations

SETBP1 interacts with SET, a negative regulator of the tumor suppressor protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A).36 SETBP1 protects SET from protease cleavage, thus increasing the amount of SET available to repress the activity of PP2A.37 In AML, SETBP1 overexpression is significantly associated with reduced survival, indicating that SETBP1 may be relevant to leukemia oncogenesis.37 SETBP1 mutations were recently identified in 25% of aCML patients, and in lower frequencies in unclassified MDS/MPN (10%),20 CMML (14.5%), and AML (<1%),38 but no mutation was identified in lymphoid leukemia or solid tumors.20 SETBP1 mutations in aCML were associated with a higher white blood cells (WBC) count at diagnosis and poorer survival.20 The prevalence of SETBP1 mutations in CNL coexpressing CSF3R T618I is 24% (Figure 2).2 Although these cases showed a trend to reduce survival, the analysis is limited by the small number of cases. Further follow-up studies are necessary to confirm these findings so that SETBP1 could be used as a prognostic marker to guide therapeutic decisions.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of CSF3R mutations and pathways activation.

Notes: CSF3R is known to signal downstream through both JAK and SRC tyrosine kinase pathways, and the two classes of CSF3R mutations exhibit different downstream signaling and kinase inhibitor sensitivities. CSF3R truncation mutations operate predominantly through SRC kinases and exhibit drug sensitivity to SRC kinase inhibitors, such as dasatinib. In contrast, CSF3R membrane proximal mutations strongly activate the JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways, and are sensitive to JAK kinase inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib.

Abbreviation: JAK, Janus kinase.

JAK2-V617F

Mutations in the JAK2 gene were first reported in 2005, and JAK2 V617F became the most frequent mutation in patients with BCR-ABL1-negative MPN, such as PV, ET, and PMF.39–42 This mutation changes a valine to a phenylalanine at position 617 and is specific to patients with myeloid neoplasm.43 The presence of this alteration is extremely important to establish the clonality and to make a differential diagnosis with reactive myeloproliferation. As observed in other myeloid neoplasms, the value of JAK2 V617F mutation founded in the 13 CNL cases was to corroborate clonality. Until now, JAK2 V617F and CSF3R T618I seems to be mutually exclusive (Figure 1).2 Further molecular studies of well-defined CNL, such as the one performed by Makishima et al38 will elucidate the role of JAK2 V617F mutation in the pathogenesis of CNL or will determine a new subgroup of MPN that does not coexpress CSF3R T618I mutation.

Additional alterations

In 2013, somatic mutations in calreticulin (CALR gene) were observed in JAK2- and MPL-negative patients (ET ~50% and PMF ~75%), making CARL mutations the second most common in MPN.44,45 Reduced frequencies were found in MDS, CMML, and aCML.46,47 Regarding CNL, only one case was reported with a novel CALR point mutation, different from the ones found in ET and PMF, and the biological significance is unknown.48

By using exome and RNA sequencing, Menezes et al21 demonstrated that the CNL genome has a combination of alterations – in addition to CSF3R T618I – that affects epigenetics (ASXL1 and TET2), spliceosome genes (LUC7L2 and U2AF1), and protein kinase (PIM3-SCO2 fusion gene). Epigenetic modifiers provide new targets for therapeutic intervention and targeting these enzymatic activities are currently being explored from a therapeutic standpoint in several types of leukemia.49,50 Interestingly, the inhibition of PIM kinases by PIM kinase inhibitors in Myc-induced lymphoma resulted in cell death.51 In this complex scenario, a combination of new targeted therapies may be considered as reasonable options for the therapeutic management of this aggressive and rare subtype of leukemia.

Clinical perspectives

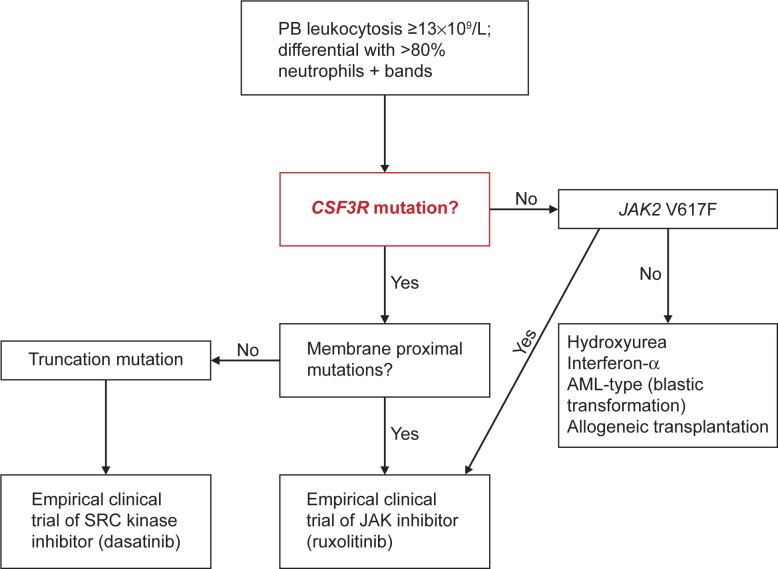

The recent discovery of CSF3R mutations and their almost invariable association with the WHO-defined CNL presents the opportunity to make significant changes in the diagnostic approach of CNL. The 2008 WHO diagnosis criteria are primarily driven by the absence of a clonal marker. Although, they require a relatively high leukocyte threshold and a list of exclusion criteria, it is equally possible to misdiagnose some cases of CNL as aCML or CMML (Table 1).

Very recently, Tefferi et al52 proposed a classification system for ET/PMF and CNL, based on the new genetic findings to be incorporated in the new WHO classification criteria for MPN. Such availability of a clonal marker for the majority of patients with CNL should allow lowering of the leukocyte level to 13×109/L, consistent with that is currently being used for the diagnosis of WHO-defined aCML (Figure 3).5 In addition, the authors proposed separate sets of major and minor criteria to accommodate the diagnostic possibility in both CSF3R-mutated and unmutated CNL. In this algorithm, diagnosis requires the presence of all three major criteria (leukocytosis WBC ≥13×109/L; segmented neutrophils/band >80% and CSF3R mutations) or, in the absence of CSF3R mutations, all minor criteria (hypercellular BM; immature granulocytes <10% in PB; no cause for neutrophilia or, if so, demonstration of clonality; no BCR-ABL1 rearrangements; and no meeting WHO diagnostic criteria for other myeloid neoplasm).

Figure 3.

Algorithm for CNL diagnosis and treatment.

Notes: The presence of a membrane proximal CSF3R mutation in a patient with predominantly neutrophilic granulocytosis should be sufficient for the diagnosis of CNL.

Abbreviations: CNL, chronic neutrophilic leukemia; PB, peripheral blood; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

Novel therapeutic approaches

Revisiting the literature, only three CNL patients, all carrying CSF3R T618I mutation, received ruxolitinib therapy.19,53,54 Interestingly, only the case who coexpressed SETBP1 mutation did not respond to this JAK inhibitor therapy. Until now, there is no evidence that the coexpression of SETBP1 is responsible for treatment failure. Defining a safe profile and clinical benefits of these treatments is extremely important to establish a prospective clinical trial of ruxolitinib and other JAK inhibitors in CNL and aCML patients. In detail, the trial will address the frequency, durability, depth, and genetic modifiers of clinical responses, such as coexisting SETBP12 or TET221 mutations. A prospective, multicenter phase II clinical trial investigating the safety and efficacy of ruxolitinib in this patient population is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02092324) and is open for participant recruitment.

Conclusion

The discovery of the high-frequency CSF3R T618I mutation in CNL identifies a new disease-defining marker, suggesting that the molecular characterization of this gene should be included in the diagnostic criteria for this disease. Given the poor prognosis of this disorder, the potential applicability of JAK or SRC kinase inhibitors is another important implication of the discovery of activating CSF3R mutation.

Acknowledgments

JM was supported by “La Caixa International PhD” fellowship. This work was supported by INTRASALUD (PI12/00425) and Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Cáncer (RTICC RD12/0036/0037) to JCC.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Elliott MA, Hanson CA, Dewald GW, Smoley SA, Lasho TL, Tefferi A. WHO-defined chronic neutrophilic leukemia: a long-term analysis of 12 cases and a critical review of the literature. Leukemia. 2005;19(2):313–317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Laborde RR, et al. CSF3R T618I is a highly prevalent and specific mutation in chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1870–1873. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohm J, Schaefer HE. Chronic neutrophilic leukaemia: 14 new cases of an uncommon myeloproliferative disease. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(11):862–864. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.11.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly JT. Chronic neutrophilic leukaemia: a distinct clinical entity? Br J Haematol. 2002;116(1):10–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the world health organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Standen GR, Jasani B, Wagstaff M, Wardrop CA. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia and multiple myeloma. An association with lambda light chain expression. Cancer. 1990;66(1):162–166. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<162::aid-cncr2820660129>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standen GR, Steers FJ, Jones L. Clonality of chronic neutrophilic leukaemia associated with myeloma: analysis using the X-linked probe M27 beta. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46(4):297–298. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nedeljkovic M, He S, Szer J, Juneja S. Chronic neutrophilia associated with myeloma: is it clonal? Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(2):439–440. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.809080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohm J, Kock S, Schaefer HE, Fisch P. Evidence of clonality in chronic neutrophilic leukaemia. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(4):292–295. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.4.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwong YL, Cheng G. Clonal nature of chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Blood. 1993;82(3):1035–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breccia M, Biondo F, Latagliata R, Carmosino I, Mandelli F, Alimena G. Identification of risk factors in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2006;91(11):1566–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurzrock R, Bueso-Ramos CE, Kantarjian H, et al. BCR rearrangement-negative chronic myelogenous leukemia revisited. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2915–2926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martiat P, Michaux JL, Rodhain J. Philadelphia-negative (Ph-) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): comparison with Ph+ CML and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. The Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. Blood. 1991;78(1):205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández JM, del Cañizo MC, Cuneo A, et al. Clinical, hematological and cytogenetic characteristics of atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(4):441–444. doi: 10.1023/a:1008393002748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Pan J, Guo J. Presence of the JAK2 V617F mutation in a patient with chronic neutrophilic leukemia and effective response to interferon Alfa-2b. Acta Haematol. 2013;130(1):44–46. doi: 10.1159/000345851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasle H, Olesen G, Kerndrup G, Philip P, Jacobsen N. Chronic neutrophil leukaemia in adolescence and young adulthood. Br J Haematol. 1996;94(4):628–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.7082329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piliotis E, Kutas G, Lipton JH. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in the management of chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(10):2051–2054. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000016087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goto H, Hara T, Tsurumi H, Tanabashi S, Moriwaki H. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia with congenital Robertsonian translocation successfully treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in a young man. Intern Med. 2009;48(7):563–567. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxson JE, Gotlib J, Pollyea DA, et al. Oncogenic CSF3R mutations in chronic neutrophilic leukemia and atypical CML. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1781–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piazza R, Valletta S, Winkelmann N, et al. Recurrent SETBP1 mutations in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(1):18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menezes J, Makishima H, Gomez I, et al. CSF3R T618I co-occurs with mutations of splicing and epigenetic genes and with a new PIM3 truncated fusion gene in chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e158. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotlib J, Maxson JE, George TI, Tyner JW. The new genetics of chronic neutrophilic leukemia and atypical CML: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2013;122(10):1707–1711. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metcalf D. The granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factors. Cell. 1985;43(1):5–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beekman R, Touw IP. G-CSF and its receptor in myeloid malignancy. Blood. 2013;115(25):5131–5136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-234120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F, Wu HY, Wesselschmidt R, Kornaga T, Link DC. Impaired production and increased apoptosis of neutrophils in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;5(5):491–501. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong F, Brynes RK, Tidow N, Welte K, Lowenberg B, Touw IP. Mutations in the gene for the granulocyte colony-stimulating-factor receptor in patients with acute myeloid leukemia preceded by severe congenital neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(8):487–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508243330804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong F, Hoefsloot LH, Schelen AM, et al. Identification of a nonsense mutation in the granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor receptor in severe congenital neutropenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(10):4480–4484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Germeshausen M, Ballmaier M, Welte K. Incidence of CSF3R mutations in severe congenital neutropenia and relevance for leukemogenesis: results of a long-term survey. Blood. 2007;109(1):93–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beekman R, Valkhof MG, Sanders MA, et al. Sequential gain of mutations in severe congenital neutropenia progressing to acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(22):5071–5077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-406116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong F, Qiu Y, Yi T, Touw IP, Larner AC. The carboxyl terminus of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor, truncated in patients with severe congenital neutropenia/acute myeloid leukemia, is required for SH2-containing phosphatase-1 suppression of Stat activation. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6447–6452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Geijn GJ, Gits J, Aarts LH, Heijmans-Antonissen C, Touw IP. G-CSF receptor truncations found in SCN/AML relieve SOCS3-controlled inhibition of STAT5 but leave suppression of STAT3 intact. Blood. 2004;104(3):667–674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward AC, van Aesch YM, Schelen AM, Touw IP. Defective internalization and sustained activation of truncated granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor found in severe congenital neutropenia/acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1999;93(2):447–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermans MH, Ward AC, Antonissen C, Karis A, Lowenberg B, Touw IP. Perturbed granulopoiesis in mice with a targeted mutation in the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor gene associated with severe chronic neutropenia. Blood. 1998;92(1):32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter MG, Avalos BR. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor mutations in severe congenital neutropenia transforming to acute myelogenous leukemia confer resistance to apoptosis and enhance cell survival. Blood. 2000;95(6):2132–2137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitsui T, Watanabe S, Taniguchi Y, et al. Impaired neutrophil maturation in truncated murine G-CSF receptor-transgenic mice. Blood. 2003;101(8):2990–2995. doi: 10.1182/blood.V101.8.2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minakuchi M, Kakazu N, Gorrin-Rivas MJ, et al. Identification and characterization of SEB, a novel protein that binds to the acute undifferentiated leukemia-associated protein SET. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268(5):1340–1351. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cristóbal I, Blanco FJ, Garcia-Orti L, et al. SETBP1 overexpression is a novel leukemogenic mechanism that predicts adverse outcome in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(3):615–625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makishima H, Yoshida K, Nguyen N, et al. Somatic SETBP1 mutations in myeloid malignancies. Nat Genet. 2013;45(8):942–946. doi: 10.1038/ng.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.James C, Ugo V, Le Couedic JP, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, et al. Cancer Genome Project Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine RL, Loriaux M, Huntly BJ, et al. The JAK2V617F activating mutation occurs in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia, but not in acute lymphoblastic leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2005;106(10):3377–3379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotunno G, Mannarelli C, Guglielmelli P, et al. Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative Investigators Impact of calreticulin mutations on clinical and hematological phenotype and outcome in essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2014;123(10):1552–1555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, et al. CALR vs JAK2 vs MPL-mutated or triple-negative myelofibrosis: clinical, cytogenetic and molecular comparisons. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1472–1477. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, et al. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2379–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2391–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasho TL, Elliott MA, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. CALR mutation studies in chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(4):450. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James LI, Frye SV. Targeting chromatin readers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93(4):312–314. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burridge S. Target watch: drugging the epigenome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(2):92–93. doi: 10.1038/nrd3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forshell LP, Li Y, Forshell TZ, et al. The direct Myc target Pim3 cooperates with other Pim kinases in supporting viability of Myc-induced B-cell lymphomas. Oncotarget. 2011;2(6):448–460. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tefferi A, Thiele J, Vannucchi AM, Barbui T. An overview on CALR and CSF3R mutations and a proposal for revision of WHO diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lasho TL, Mims A, Elliott MA, Finke C, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia with concurrent CSF3R and SETBP1 mutations: single colony clonality studies, in vitro sensitivity to JAK inhibitors and lack of treatment response to ruxolitinib. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1363–1365. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dao KH, Solti MB, Maxson JE, et al. Significant clinical response to JAK1/2 inhibition in a patient with CSF3R-T618I-positive atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res Rep. 2014;3(2):67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]