Abstract

Background/Aims

The diagnostic yield of fecal leukocyte and stool cultures is unsatisfactory in patients with acute diarrhea. This study was performed to evaluate the clinical significance of the fecal lactoferrin test and fecal multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in patients with acute diarrhea.

Methods

Clinical parameters and laboratory findings, including fecal leukocytes, fecal lactoferrin, stool cultures and stool multiplex PCR for bacteria and viruses, were evaluated prospectively for patients who were hospitalized due to acute diarrhea.

Results

A total of 54 patients were included (male, 23; median age, 42.5 years). Fecal leukocytes and fecal lactoferrin were positive in 33 (61.1%) and 14 (25.4%) patients, respectively. Among the 31 patients who were available for fecal pathogen evaluation, fecal multiplex PCR detected bacterial pathogens in 21 patients, whereas conventional stool cultures were positive in only one patient (67.7% vs 3.2%, p=0.000). Positive fecal lactoferrin was associated with presence of moderate to severe dehydration and detection of bacterial pathogens by multiplex PCR (21.4% vs 2.5%, p=0.049; 100% vs 56.5%, p=0.032, respectively).

Conclusions

Fecal lactoferrin is a useful marker for more severe dehydration and bacterial etiology in patients with acute diarrhea. Fecal multiplex PCR can detect more causative organisms than conventional stool cultures in patients with acute diarrhea.

Keywords: Acute diarrhea, Fecal lactoferrin, Fecal leukocytes, Multiplex polymerase chain reaction

INTRODUCTION

About half the population of the world is affected with diarrhea every year and diarrhea remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Infection is the most common cause of acute diarrhea, but microbiological tests are not usually required unless patients present with dehydration, fever, or bloody feces since most acute diarrheal illnesses are self-limited and the diagnostic yield of stool cultures ranges from only 1.5% to 5.6%.1

The presence of fecal leukocytes is believed to suggest an inflammatory etiology and a more serious illness in patients with acute diarrhea and further diagnostic workup such as stool cultures may be indicated.2 However, the results of microscopy are largely dependent on the technician and the freshness of the specimen.3 In contrast, lactoferrin, which is a major constituent in the second granules of neutrophils, can be a useful marker for fecal leukocytes,4 and an increase of fecal lactoferrin is related to greater disease severity in children with infectious diarrhea.5 The test can detect lactoferrin even after the morphologic loss of leukocytes and the subjectivity in the reading is minimal.3

Accurate and rapid detection of causative organisms in patients with acute diarrhea may be helpful for decreasing the duration of morbidity and complications. Recently, simultaneous and rapid detection of pathogens in patients with acute diarrhea is enabled by multiplex molecular biology techniques, which are expected to be more sensitive than conventional cultures and highly specific.6

Thus, this study was performed to evaluate the clinical significance of noninvasive fecal markers including lactoferrin and multiplex PCR in patients with moderate to severe acute diarrhea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The prospective study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital. From June 2010 to August 2011, patients were included according to the following criteria: age (20 to 80 years), acute diarrheal symptoms (≥5 times/day) within 2 weeks, and hospitalization due to diarrhea-associated symptoms or signs (dehydration, fever >37°C, or bloody diarrhea). Patients with underlying gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel syndrome, gastrointestinal cancer, liver cirrhosis, chronic pancreatitis, hospital-acquired diarrhea, administration of antibiotics within 1 month, or other chronic diseases requiring intensive care were excluded. Clinical parameters including bloody diarrhea, dehydration, duration of diarrhea, length of hospital stay, and complications including acute kidney injury (serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL) were also evaluated. Moderate to severe dehydration was defined when the patient showed orthostatic hypotension (decrease in systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg at standing position), overt hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 80 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure less than 60 mm Hg), or mental aberration (mental status other than alert).

Conservative care including parenteral hydration was provided for all the patients, and intravenous ciprofloxacin 500 mg was administered twice a day to patients with fever. Use of antibiotics was delayed until stool specimens were obtained. All the stool specimens were collected within 24 hours after admission.

1. Inflammatory markers

Routine blood tests including complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), and fecal tests including microscopic examination of leukocytes, a latex agglutination assay for detection of lactoferrin (LEUKO-TEST; TechLab, Blacksburg, VA, USA), and a quantitative immunochemical occult blood test (OC-Sensor Diana; Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were performed within 24 hours after admission. Fecal leukocytes were examined under a microscope by two laboratory technicians and cross-checked within 2 hours after collection.

2. Pathogen detection by conventional fecal cultures and multiplex PCR

Conventional stool cultures using selective agars for Salmonella, Shigella, and Vibrio species (spp.) were performed for all patients. Multiplex PCR using the SeeplexⓇ Diarrhea ACE detection kit (Seegene, Seoul, Korea) was performed on 10 bacteria (Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Vibrio spp., Clostridium difficile toxin B, C. perfringens, Yersinia enterocolitica, Aeromonas spp., Escherichia coli O157:H7, and verocytotoxin-producing E. coli [VTEC]) and four viruses (Group A rotavirus, norovirus GI/GII, enteric adenovirus, and astrovirus) when the amount of the fecal specimens were sufficient for the test.

3. Sigmoidoscopy

Within 48 hours after admission, sigmoidoscopy was performed without bowel preparation after informed consent. The endoscope was inserted until the patient complained of procedure-related pain (≥numeric rate scale 4).

4. Statistical analysis

The results are presented as median (range) or number (percentage). All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data were tested using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for small expected frequencies. Mann-Whitney U-test was used for continuous data. Detection rates for fecal bacterial pathogens between conventional stool cultures and multiplex PCR were compared with the McNemar test. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 54 patients was included in this study. The median age of patients was 42.5 years (range, 20 to 74 years), and the clinical parameters and findings are summarized in Table 1. The median values for frequency of diarrhea and duration of diarrhea were 10 times/day (range, 5 to 30 times/day) and 6 days (range, 2 to 13 days), respectively. Bloody diarrhea for 10 patients (18.5%), fever for 24 patients (44.4%), and moderate to severe dehydration for four patients (7.4%) were found. Acute kidney injury as a complication was present in four patients (7.4%).

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Parameters and Findings for a Total of 54 Patients

| Clinical finding | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 42.5 (20–74) |

| Male sex | 23 (42.6) |

| Diarrhea, times/day* | 10 (5–30) |

| Bloody diarrhea* | 10 (18.5) |

| Fever* | 24 (44.4) |

| Moderate to severe dehydration* | 4 (7.4) |

| Duration of diarrhea, day* | 6 (2–13) |

| Acute kidney injury* | 4 (7.4) |

| Bacteria detected by multiplex PCR (n=31)* | 21 (67.7) |

| Virus detected by multiplex PCR (n=31)* | 4 (12.9) |

| Mucosal erosion or ulcer (n=44)* | 16 (36.4) |

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Clinical parameters in this study.

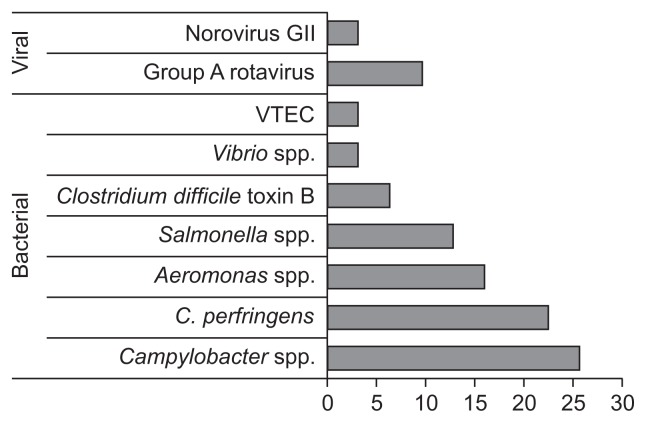

Causative pathogens were detected in only one patient (Salmonella spp. Group C) by conventional cultures (1/54, 1.9%). However, various pathogens were detected in 24 out of 31 patients (77.4%) who were available for multiplex PCR assays as follows: 28 bacteria for 21 patients, five viruses for four patients, one coinfection of a bacterium and a virus for a patient. Campylobacter spp. (25.8%) were most prevalent, followed by C. perfringens (22.6%), Aeromonas spp. (16.1%), Salmonella spp. (12.9%), Group A rotavirus (9.7%), C. difficile toxin B (6.5%), norovirus GII (3.2%), Vibrio spp. (3.2%), and VTEC (3.2%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathogens detected by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (n=31). Values are presented as percentages.

VTEC, verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli.

The detection rate of fecal bacterial pathogens was significantly higher for multiplex PCR than for conventional stool cultures (67.7% vs 3.2%, p=0.000).

Among 44 patients who received sigmoidoscopy, mucosal erosion or ulcers were found in 16 patients (36.4%).

1. Inflammatory markers

Among 54 patients, 33 (61.1%) were positive for fecal leukocytes, 14 (25.9%) for fecal lactoferrin, and 34 (63.0%) for fecal occult blood (Table 2). The median value of CRP was 51.1 mg/L (range, 1.9 to 310.6 mg/L).

Table 2.

Summary of Laboratory Findings and Inflammatory Markers for the 54 Patients

| Laboratory finding | Value |

|---|---|

| Fecal leukocytes-positive* | 33 (61.1) |

| Fecal lactoferrin-positive* | 14 (25.9) |

| Fecal occult blood-positive* | 34 (63.0) |

| ESR, mm/hr | 14 (1–83) |

| CRP, mg/L* | 51.1 (1.9–310.6) |

| Leukocytes, /μL | 9,960 (2,040–33,000) |

| Neutrophil ratio, % | 77.8 (35.0–92.0) |

| Lymphocyte ratio, % | 11.6 (2.0–48.0) |

| Platelets, /μL | 207,000 (101,000–313,000) |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (range).

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Inflammatory markers in this study.

2. Correlation between clinical parameters and inflammatory markers

Clinical parameters including frequency of diarrhea, fever, moderate to severe dehydration, duration of diarrhea, acute kidney injury, and bacterial and/or viral pathogen detection by multiplex PCR were not different statistically between fecal leukocyte-positive and negative groups (Table 3). However, moderate to severe dehydration was more prevalent in the fecal lactoferrin-positive group than in the negative group (21.4% vs 2.5%, p=0.049). Bacterial detection by multiplex PCR was also more frequent in the fecal lactoferrin-positive group than in the negative group (100% vs 56.5%, p=0.032). Thirteen bacterial pathogens were detected in eight lactoferrin-positive patients as follows: Campylobacter spp. (5), C. perfringens (2), Aeromonas spp. (2), Salmonella spp. (2), C. difficile toxin B (1), and Vibrio spp. (1). Of them, Campylobacter spp. were more prevalent in the lactoferrin-positive group than in the negative group (62.5% vs 13.0%, p=0.013) while there was no statistically significant difference among other types of bacterial pathogens between lactoferrin-positive and negative groups.

Table 3.

Differences (p-Values) in Clinical Parameters in the Fecal Leukocyte, Lactoferrin, and Occult Blood-Positive versus Negative Groups

| Fecal leukocytes | Fecal lactoferrin | Fecal occult blood | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea, times/day | 0.239 | 0.959 | 0.207 |

| Fever | 0.263 | 0.540 | 1.000 |

| Moderate to severe dehydration | 0.638 | 0.049 | 1.000 |

| Duration of diarrhea, day | 0.687 | 0.604 | 0.172 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.622 |

| Bacterial pathogen detection by multiplex PCR (n=31) | 0.697 | 0.032 | 0.423 |

| Viral pathogen detection by multiplex PCR (n=31) | 1.000 | 0.550 | 1.000 |

| Mucosal erosion or ulcer (n=44) | 0.352 | 0.724 | 0.510 |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Although there was no statistically significant difference in detection rates of bacterial pathogens by multiplex PCR between fecal occult blood positive and negative groups, Campylobacter spp. were more prevalent in the fecal occult blood-positive group than in the negative group (40.0% vs 0.0%, p=0.028).

All the clinical parameters including frequency of diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, fever, moderate to severe dehydration, duration of diarrhea, acute kidney injury, bacterial and viral pathogen detection by multiplex PCR, and mucosal erosion or ulcers were not correlated significantly with CRP levels.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that fecal lactoferrin can be a more useful clinical marker than fecal leukocyte testing in patients with acute diarrhea. Positive fecal lactoferrin was significantly associated with presence of moderate to severe dehydration and fecal bacterial pathogen detection by multiplex PCR. These findings are comparable with the results of a previous report by Chen et al.5 that showed an increase of fecal lactoferrin during bacterial infection and association with greater disease severity in children. In contrast, fecal leukocytes did not show any significant correlation with the clinical parameters evaluated in this study even though an attempt to increase diagnostic accuracy was made by cross-checking by two expert technicians.

So far, fecal lactoferrin has been considered a useful noninvasive test for differentiating inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) from irritable bowel syndrome or differentiating active IBD from inactive IBD.7–9 However, the results of our study suggested that fecal lactoferrin can also be used as a marker for presence of more severe dehydration and bacterial etiology in patients with acute diarrhea.

Secondly, fecal multiplex PCR detected significantly more bacterial pathogens than conventional stool cultures and also detected viral pathogens simultaneously. This result is compatible with previous studies using fecal multiplex PCR.10–12 According to the study using stool samples collected from 245 pediatric patients with suspected infectious gastroenteritis, multiplex PCR was found to have a higher level of sensitivity than our routine detection methods for common enteric pathogens, with the exception of Salmonella spp. and C. difficile. However, multiplex PCR did not always result in a significant improvement in specificity.13

Although most cases of acute infectious diarrhea are self-limited, the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy has been addressed in selected patients with bacterial diarrhea.14,15 However, antibiotics should be avoided in patients with VTEC infection since there is concern about an increase in the risk of hemolytic-uremic syndrome.16 Thus, earlier and more accurate detection of pathogens may be very helpful for appropriate management in patients with acute diarrhea.

Bloody diarrhea is known to be helpful for discrimination of infectious colitis including Salmonella, Shigella, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, and Campylobacter from noninfective colitis.17,18 However, fecal occult blood is more helpful than gross hematochezia for diagnosis of bacterial infectious colitis causing variable amounts of intestinal mucosal bleeding.18 This finding is compatible with the result of our study that detection of Campylobacter spp. was associated with a positive fecal occult blood test.

There may be some limitations to the present study. First, a relatively small number of patients were enrolled in the study. Secondly, the possibility of “innocent bystanders” among pathogens detected by multiplex PCR exists since a certain amount of infectious dose is required for the onset of an illness.

In conclusion, fecal lactoferrin is a useful marker for more severe dehydration and bacterial etiology in patients hospitalized for acute diarrhea. Fecal multiplex PCR can detect more causative organisms than conventional stool cultures and therefore may be helpful for management of patients with acute diarrhea.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Clinical Research Laboratory Foundation Program of Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:331–351. doi: 10.1086/318514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerrant RL, Shields DS, Thorson SM, Schorling JB, Gröschel DH. Evaluation and diagnosis of acute infectious diarrhea. Am J Med. 1985;78:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi SW, Park CH, Silva TM, Zaenker EI, Guerrant RL. To culture or not to culture: fecal lactoferrin screening for inflammatory bacterial diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:928–932. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.928-932.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerrant RL, Araujo V, Soares E, et al. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1238–1242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1238-1242.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CC, Chang CJ, Lin TY, Lai MW, Chao HC, Kong MS. Usefulness of fecal lactoferrin in predicting and monitoring the clinical severity of infectious diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4218–4224. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Leary J, Corcoran D, Lucey B. Comparison of the EntericBio multiplex PCR system with routine culture for detection of bacterial enteric pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3449–3453. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01026-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayakawa T, Jin CX, Ko SB, Kitagawa M, Ishiguro H. Lactoferrin in gastrointestinal disease. Intern Med. 2009;48:1251–1254. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisbert JP, McNicholl AG, Gomollon F. Questions and answers on the role of fecal lactoferrin as a biological marker in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1746–1754. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KM. Fecal biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2013;11:73–78. doi: 10.5217/ir.2013.11.2.73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coupland LJ, McElarney I, Meader E, et al. Simultaneous detection of viral and bacterial enteric pathogens using the SeeplexⓇ Diarrhea ACE detection system. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:2111–2121. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812002622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins RR, Beniprashad M, Cardona M, Masney S, Low DE, Gubbay JB. Evaluation and verification of the Seeplex Diarrhea-V ACE assay for simultaneous detection of adenovirus, rotavirus, and norovirus genogroups I and II in clinical stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3154–3162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00599-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baek SJ, Kim SH, Lee CK, et al. Relationship between the severity of diversion colitis and the composition of colonic bacteria: a prospective study. Gut Liver. 2014;8:170–176. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2014.8.2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onori M, Coltella L, Mancinelli L, et al. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of bacterial and viral enteropathogens in stool samples of paediatric patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dryden MS, Gabb RJ, Wright SK. Empirical treatment of severe acute community-acquired gastroenteritis with ciprofloxacin. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:1019–1025. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J, Ekdahl K. A meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:696–700. doi: 10.1086/509924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Ryan M, Prado V. Risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010263431716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones R, Rubin G. Acute diarrhoea in adults. BMJ. 2009;338:b1877. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Clinical practice: acute infectious diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:38–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp031534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]