Abstract

Background/Aims

Recent papers have highlighted the role of diet and lifestyle habits in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but very few population-based studies have evaluated this association in developing countries. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between diet and lifestyle habits and IBS.

Methods

A food frequency and lifestyle habits questionnaire was used to record the diet and lifestyle habits of 78 IBS subjects and 79 healthy subjects. Cross-tabulation analysis and logistic regression were used to reveal any association among lifestyle habits, eating habits, food consumption frequency, and other associated conditions.

Results

The results from logistic regression analysis indicated that IBS was associated with irregular eating (odds ratio [OR], 3.257), physical inactivity (OR, 3.588), and good quality sleep (OR, 0.132). IBS subjects ate fruit (OR, 3.082) vegetables (OR, 3.778), and legumes (OR, 2.111) and drank tea (OR, 2.221) significantly more frequently than the control subjects. After adjusting for age and sex, irregular eating (OR, 3.963), physical inactivity (OR, 6.297), eating vegetables (OR, 7.904), legumes (OR, 2.674), drinking tea (OR, 3.421) and good quality sleep (OR, 0.054) were independent predictors of IBS.

Conclusions

This study reveals a possible association between diet and lifestyle habits and IBS.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Food, Diet habits, Life style, Odds ratio

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorder in the absence of any structural, physiological, or biochemical abnormalities in the GI tract. Functional GI disorders are common in developed countries, and IBS is the most frequent of these disorders. The worldwide prevalence of IBS varies according to the location, diagnostic criteria, and design of the study from 1.1% to 22%.1–3 Patients with IBS have been found to have a considerable reduction in quality of life.4–6 IBS reduces quality of life to the same degree of impairment as major chronic diseases, such as hepatic cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, and diabetes.4,7,8

The etiology of IBS is poorly understood and many factors are involved, including genetics, heritability, gut hypersensitivity, intestinal microbiota, low-grade mucosal inflammation, disturbed colonic motility, previous GI infection, and disturbances in the gut neuroendocrine system (NES).6,9,10 Many subjects with IBS relate their symptoms to their food intake. In other words, certain foods may precipitate or aggravate IBS symptoms.11–16

Interestingly, an association between diet and lifestyle habits and IBS has been reported by several investigators.11,17–19 IBS patients are affected by sleep impairment, eating habits, diet, exercise, and other lifestyle factors.19 A diet with low amounts of fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FOD-MAPs) has been found to be efficient in alleviating GI symptoms in IBS patients.17,18 Moreover, a diet with a high content of fat and spicy foods is thought to give rise to GI symptoms.11

Conceivably, a combination of diet and lifestyle habits may cause GI symptoms in IBS patients. However, most investigators have evaluated the association between IBS and diet or lifestyle habits, and very few surveys have been performed to explore the association between diet and lifestyle habits and IBS at the same time. Moreover, most of the literature on IBS has focused on Western industrialized societies, and no surveys have been performed in Chinese populations. Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate the association between diet and lifestyle habits and IBS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Research subjects

The study cohort included consecutive inpatients admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology from January 2011 to December 2012 who fulfilled the Rome III Diagnostic Criteria for IBS.2 These criteria include symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort and a marked change in bowel habit for at least 6 months, with symptoms experienced on at least three days of at least 3 months. Two or more of the following must apply: (1) onset of pain is related to a change in frequency of stool; (2) onset of pain is related to a change in the appearance of stool; and (3) pain is relieved by a bowel movement.

In addition to the Rome III Diagnostic Criteria for IBS, the study cohort fulfilled the following criteria: (1) no evidence of esophagitis, esophageal ulcer, GI tumors, and cholecystitis on upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy, and transabdominal ultrasonography and (2) limitation of onset of the symptoms to one year before hospitalization in order to avoid memory bias. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with a history of pharmacologic therapy and (2) patients with a previous medical history such as abdominal surgery, which could cause abdominal symptoms before the actual diagnosis of IBS.

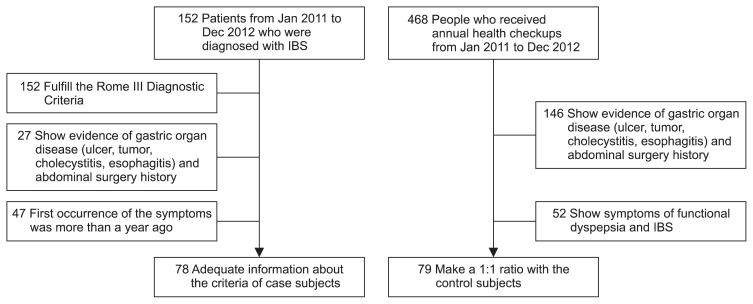

Eventually, a total of 78 subjects were enrolled in the case group. The control group included 79 healthy subjects who received annual health checkups in the Department of Health (Fig. 1). All subjects provided written consent to participate in the study. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board at Southern Medical University. This study complies with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and current ethical guidelines.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart.

Jan, January; Dec, December; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

2. Research methods

A Chinese questionnaire was designed to evaluate the diet and lifestyle habits of adults in China. The contents of the questionnaire include the following four parts:

1) Sociodemographic variables

Age, gender, height, weight, educational level, and job were recorded. Educational level was categorized into the following three classes: low (no school, elementary school, or junior high school only), medium (high school), and high (college or university).

2) Health-related conditions and lifestyle habits

Smoking status was dichotomized as “smoker” or “nonsmoker.” Drinking status was dichotomized as “drinker” if alcohol was consumed at least weekly or “nondrinker” if alcohol was consumed less often. Physical activity status was dichotomized as “physically active” if the subject exercised at least weekly or “physically inactive” if the subject exercised less often. In addition, each subject’s body mass index (BMI) was recorded based on the Chinese guidelines in four categories: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 to 23.9 kg/m2), overweight (24.0 to 27.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥28.0 kg/m2). BMI was calculated using the international standard formula: BMI=mass (kg)/[height (m)]2. Moreover, sleep quality was categorized according to the definition of insomnia:20 sleep disturbance (difficulty sleeping occurs at least 3 times per week, and these difficulties have occurred for at least 1 month) or good quality sleep (difficulty sleeping occurs less than 3 times per week, and these difficulties have not occurred for 1 month). The term difficulty sleeping must fulfill the following criteria:20 (1) difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or nonrestorative sleep; (2) this difficulty is present despite adequate opportunity and circumstance to sleep; and (3) this impairment in sleep is associated with daytime impairment or distress.

3) Dietary habits

Time spent eating was categorized in three classes: less than 10 minutes, 10 to 20 minutes, and more than 20 minutes. In addition, the subjects recorded the following dietary habits: eating late-night snacks, eating meals with family or outside the home, having meals on time, and picky eating habits.

4) Food preference

Ten food categories were established based on Chinese dietary habits. Consumption frequencies in each category were calculated and cut off into the following classes by the medians.

When the median was more than 1 time per day, consumption was categorized as “several times a day” or “once a day or less.”

When the median was 1 time a day, it was categorized as “at least once a day” or “less than once a day.”

When the median was more than 1 time a week, it was categorized as “at least several times a week” or “once a week or less.”

When the median was 1 time a week, it was categorized as “at least once a week” or “less than once a week.”

When the median was less than 1 time a week, it was categorized as “monthly” or “never or rarely.”

The data were collected through the questionnaire survey. The length of each interview was limited to 20 to 30 minutes to obtain relevant recall information about the period of time 6 months before the first occurrence of the syndrome. Every patient had enough time during the interview to provide recall information.

3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed with SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Student t-test and chi-square test were used to evaluate differences in sociodemographic variables between patients and controls. Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) and p-value. Subjects were divided into two categories by consumption (less than median frequency and equal or more than the median frequency). Cross-tabulation analysis (chi-square test) was used initially to reveal any association between health-related conditions, lifestyle habits, dietary habits, and food preferences. Then, the logistic regression (binary, univariate) was used to determine significant predictors of IBS derived from the initial analysis. Finally, to evaluate variables responsible for IBS, a multivariate analysis was performed by stepwise multiple logistic regression. Data are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

RESULTS

1. IBS and sociodemographic variables

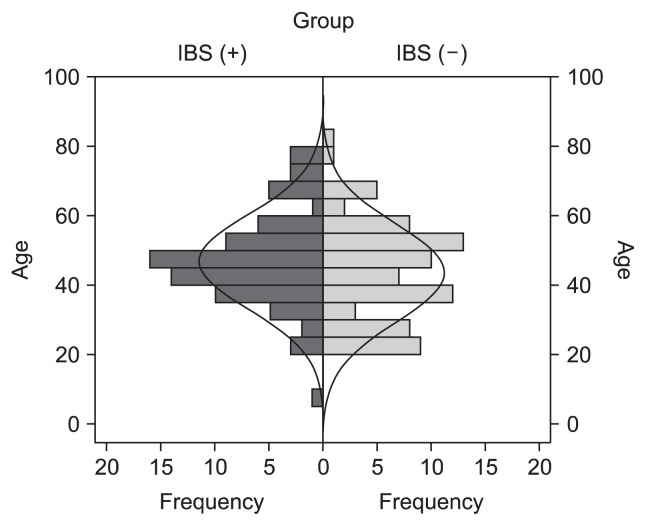

Among the total 157 subjects, there were no differences in age, gender, height, weight, and educational level between the two groups (Table 1). However, the evaluation of the age distribution indicated increased prevalence of IBS in subjects above the age of 30 (p<0.05) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Information

| Sociodemographic characteristic | IBS patients (n=78) | Control subjects (n=79) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 46.76±13.58 | 43.41±14.06 | 0.131 |

| Sex, male/female | 37/41 | 44/35 | 0.300 |

| Height, m | 1.63±0.72 | 1.65±0.75 | 0.204 |

| Weight, kg | 60.28±10.60 | 62.60±11.41 | 0.189 |

| Duration of education, low/middle/high* | 28/19/31 | 24/24/31 | 0.643 |

Data are presented as the mean±SD or number.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Educational level was categorized into the following three classes: low (no school, elementary school, or junior high school only), medium (high school) and high (college or university).

Fig. 2.

Age distribution of the case-control subjects.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

2. IBS, health-related behaviors/conditions, and lifestyle habits

The data shown in Table 2 reveal significant differences in physical activity and sleep quality between groups. Subjects who were physically inactive were 3.588 times more likely to suffer from IBS than those who were physically active (95% CI, 1.728 to 7.449; p<0.01). Moreover, those with good quality sleep were 0.132 times less likely to suffer from IBS less than those who had sleep disturbances (95% CI, 0.051 to 0.340; p<0.01).

Table 2.

Health Behaviors, Conditions, and Lifestyle Habits

| Behaviors, conditions, and habits | IBS patients (n=78) | Control subjects (n=79) | p-value | Univariate logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker | 17 (21.8) | 15 (19.0) | 0.662 | -* |

| Drinker | 25 (32.1) | 29 (36.7) | 0.539 | - |

| Physically inactive | 34 (43.6) | 14 (17.7) | 0.001 | 3.588 (1.728–7.449) |

| Good quality sleep | 48 (61.5) | 73 (92.4) | 0.000 | 0.132 (0.051–0.340) |

| BMI | 0.582 | - | ||

| Underweight | 5 (6.4) | 5 (6.3) | - | - |

| Normal | 57 (73.1) | 52 (65.8) | - | - |

| Overweight | 14 (17.9) | 21 (26.6) | - | - |

| Obese | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | - | - |

Data are presented as number (%).

Variables with p-values that were not significant according to the chi-square test were not included in the univariate logistic regression.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

3. IBS and dietary habits

Subjective perceptions of irregular eating were evaluated. Irregular eating is a behavior defined as not eating meals regularly each day, and having long periods between each meal, including breakfast, lunch, and supper. These subjective perceptions of irregular eating were more frequent among IBS patients (65.4%) than control subjects (36.7%) (p<0.01) as shown in Table 3. Subjects with irregular eating habits were 3.257 times more likely to suffer from IBS than those with regular eating habits (95% CI, 1.694 to 6.259; p<0.01). There were no significant differences in other dietary habits (time spent eating, eating late-night snacks, having meals with family or outside the home, having meals on time, and picky eating habits) between groups.

Table 3.

Dietary Habits

| Dietary habits | IBS patients (n=78) | Control subjects (n=79) | p-value | Univariate logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular eating | 51 (65.4) | 29 (36.7) | 0.000 | 3.257(1.694–6.259) |

| Eating late-night snacks | 21 (26.9) | 19 (24.1) | 0.680 | -* |

| Time spent eating, min | 0.269 | - | ||

| <10 | 28 (35.9) | 19 (24.1) | - | - |

| 10–20 | 35 (44.9) | 42 (53.2) | - | - |

| >20 | 15 (19.2) | 18 (22.8) | - | - |

| Meals with family | 59 (75.6) | 56 (70.9) | 0.501 | - |

| Picky eating habits | 56 (71.8) | 59 (74.7) | 0.683 | - |

Data are presented as number (%).

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Variables with p-values that were not significant according to the chi-square test were not included in the univariate logistic regression.

4. IBS and food preference

Using the median as the cutoff for food consumption frequency, there were differences between the two groups in the following categories: fruit (p<0.05), vegetables (p<0.01), legumes (p<0.05), and tea (p<0.05) (Table 4). For the rest of the food categories, i.e., noodles, canned foods, pickled foods, sweetmeats (cakes, ice cream, and cream), milk, coffee, and carbonated drinks, there were no statistically significant differences in food preference between groups.

Table 4.

Frequency of Food Consumption in Various Food Categories

| Food category and frequency of food consumption | IBS patients (n=78) | Control subjects (n=79) | p-value | Univariate logistic regression OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | 10.129 (p<0.05) | 3.082 (1.521–6.248) | ||

| Once a week or less | 16 (20.5) | 35 (44.3) | ||

| At least once a week | 62 (79.5) | 44 (55.7) | ||

| Vegetables | 13.014 (p<0.001) | 3.778 (1.796–7.947) | ||

| Once a day or less | 13 (16.7) | 34 (43.0) | ||

| Several times a day | 65 (83.3) | 45 (57.0) | ||

| Legumes | 5.355 (p<0.05) | 2.111 (1.117–3.991) | ||

| Once a week or less | 32 (41.0) | 47 (59.5) | ||

| At least once a week | 46 (59.0) | 32 (40.5) | ||

| Tea | 5.646 (p<0.05) | 2.221 (1.144–4.312) | ||

| Monthly or rare | 42 (53.8) | 57 (72.2) | ||

| At least once a week | 36 (46.2) | 22 (27.8) | ||

| Noodles | 0.051 (p>0.05) | 1.078 (0.562–2.066) | ||

| Once a week or less | 49 (62.8) | 51 (64.6) | ||

| At least once a week | 29 (37.2) | 28 (35.4) | ||

| Canned food | 1.058 (p>0.05) | 0.575 (0.198–1.667) | ||

| Monthly | 6 (7.7) | 10 (12.7) | ||

| Never or rarely | 72 (92.3) | 69 (87.3) | ||

| Pickled foods | 0.006 (p>0.05) | 1.026 (0.549–1.198) | ||

| Monthly | 39 (50.0) | 39 (49.4) | ||

| Never or rarely | 39 (50.0) | 40 (50.6) | ||

| Sweetmeats | 1.558 (p>0.05) | 1.533 (0.782–3.005) | ||

| Once a week or less | 49 (62.8) | 57 (72.2) | ||

| At least once a week | 29 (37.2) | 22 (27.8) | ||

| Milk | 1.936 (p>0.05) | 0.636 (0.335–1.205) | ||

| Once a week or less | 50 (64.1) | 42 (53.2) | ||

| At least once a week | 28 (35.9) | 37 (46.8) | ||

| Coffee | 3.029 (p>0.05) | 0.450 (0.180–1.123) | ||

| Monthly | 8 (10.3) | 16 (20.3) | ||

| Never or rarely | 70 (89.7) | 63 (79.7) | ||

| Carbonated drinks | 0.026 (p>0.05) | 0.938 (0.427–2.058) | ||

| Monthly | 15 (19.2) | 16 (20.3) | ||

| Never or rarely | 63 (80.8) | 63 (79.7) |

Data are presented as number (%).

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

5. Multivariable logistic regression

In the logistic step-by-step regression for the factors mentioned above with statistical differences between groups, the interference factors, i.e., age and gender, were eliminated from the model. The following variables were included in the final model: physical inactivity, irregular eating, good quality sleep, vegetables, tea, and legumes (Table 5). Compared with the univariate logistic regression, fruit was not included in the final multivariable logistic model. The rest of the variables were consistent with the single-factor results.

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome

| Factor | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical inactivity | 0.000 | 6.297 (2.294–17.286) |

| Good quality sleep | 0.000 | 0.054 (0.015–0.190) |

| Irregular eating | 0.002 | 3.963 (1.666–9.427) |

| Vegetables | 0.000 | 7.904 (2.889–21.620) |

| Legumes | 0.025 | 2.674 (1.130–6.325) |

| Tea | 0.008 | 3.421 (1.383–8.461) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

As a functional GI disorder, IBS has been shown to be associated many kinds of factors.6,9,10 This study is the first case-control study to examine the effect of lifestyle and diet on IBS patients in a developing country—China. This research demonstrates that a poor lifestyle and poor dietary habits, such as physical inactivity, sleep disturbance, and irregular eating, increase the risk of IBS. Alternatively, the consumption of fruit, vegetables, and tea may also induce IBS symptoms.

In the present study, the prevalence of IBS was higher in women, as previously reported by others,21,22 but this difference did not reach statistical significance. However, the evaluation of the age distribution indicated increased prevalence of IBS in subjects above the age of 30. This result is in contrast to a previous report that showed that IBS incidence decreased with age,23 but our results match those of other studies showing that the prevalence of IBS was high in the elderly24 and an overlooked problem.25 The population sample in the present study had a high mean age (Table 1). Increasing age was associated with higher consultation rates in our study. There were more IBS subjects older than 30 years of age than there were IBS subjects younger than 30 years of age (Fig. 2). There is also a possibility of a volunteer bias. These associations may explain the higher prevalence of IBS in older people in our sample.

Sleep disturbance was independently associated with IBS in the general population.26–28 Our results confirmed these observations from a different perspective, as subjects with good quality sleep were less likely to have IBS than subjects without good quality sleep. It is possible that patients with IBS may exhibit a longer duration of the rapid eye movement (REM) phase of sleep, as REM sleep is associated with increased colonic propagating and nonpropagating motility, which could theoretically predispose an individual to develop IBS symptoms through the induction of persistent motor activity.29 However, this hypothesis has not been confirmed by other studies.

Similar to previous results, physical factors affected IBS.30 Increased physical activity improves GI symptoms in IBS patients. Physically active patients with IBS have less symptom deterioration compared with physically inactive patients. Physical activity might be used as a primary treatment modality in IBS patients.31 Educational level, smoking, and alcohol intake did not influence the prevalence of IBS. However, in different populations, those with higher educational levels were more likely to be physically active32 and have a healthy diet.33 These factors would help decrease IBS incidence. However, anxiety may be more common in people with a higher educational level, which could lead to sleep disturbance and increase IBS incidence. Further studies are needed to explore these kinds of associations.

Similar to the results of an earlier report,19 IBS patients had significantly more irregular meal habits than those without IBS. It is possible that irregular eating may lead to disturbed colonic motility and cause GI symptoms in IBS patients. Further studies are needed to examine the mechanisms that explain this association.

We developed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to assess habitual intake, which was shown to be appropriate for exploring dietary patterns based on frequencies but not for estimating total intakes of energy or nutrients.34,35 Furthermore, the reproducibility and validity of major FFQ dietary patterns were previously found to be satisfactory for studying diet-disease relationships.36 In our study, certain categories of food (vegetables, legumes, fruit, and tea) were significantly related to IBS. Foods may contribute to symptom onset through several mechanisms including food allergy and intolerance. Moreover, certain foods may alter the composition of the luminal milieu, either directly or indirectly through effects on bacterial metabolism. Finally, IBS symptoms may develop following exposure to food-borne pathogens.37 A specific food intolerance (for example, lactase deficiency) may explain the symptoms of some patients. In addition, fiber-rich products may promote intestinal peristalsis, which may also increase intestinal dysfunction. Tea contains salicylates, which may cause gut symptoms.22,38–43 In contrast with a previous report,41 milk was not significantly related to IBS in our study. This discrepancy may be related to the differences between the Chinese and Western diets and the low penetration of milk consumption in the Chinese population.

Many subjects with IBS relate their symptoms to their food intake.11,12 Most of these subjects modify their diets, and these modifications sometimes result in an inadequate diet.12 Mazzawi et al.44 and Ostgaard et al.45 studied the effects of dietary guidance on the symptoms, quality of life, and habitual diets of IBS patients. They found that individual dietary guidance is a costeffective option for the management of IBS. Moreover, dietary guidance promoted healthier diets, improved the quality of life, and reduced IBS symptoms in IBS patients.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that lifestyle and dietary factors influence the occurrence of IBS, and these findings may guide future cohort studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2011).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sorouri M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, et al. Functional bowel disorders in Iranian population using Rome III criteria. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:154–160. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoshkrood-Mansoori B, Pourhoseingholi MA, Safaee A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: a population based study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:413–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rey E, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: novel views on the epidemiology and potential risk factors. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li FX, Patten SB, Hilsden RJ, Sutherland LR. Irritable bowel syndrome and health-related quality of life: a population-based study in Calgary, Alberta. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:259–263. doi: 10.1155/2003/706891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehead WE, Burnett CK, Cook EW, 3rd, Taub E. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2248–2253. doi: 10.1007/BF02071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151–5163. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161–176. doi: 10.1023/A:1008970312068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank L, Kleinman L, Rentz A, Ciesla G, Kim JJ, Zacker C. Health-related quality of life associated with irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with other chronic diseases. Clin Ther. 2002;24:675–689. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(02)85143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parry S, Forgacs I. Intestinal infection and irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:5–9. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simrén M1, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63:108–115. doi: 10.1159/000051878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:667–672. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, et al. What patients know about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National survey on patient educational needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational Needs Questionnaire (PEQ) Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1972–1982. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dainese R, Galliani EA, De Lazzari F, Di Leo V, Naccarato R. Discrepancies between reported food intolerance and sensitization test findings in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1892–1897. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarrett M, Visser R, Heitkemper M. Diet triggers symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. The patient’s perspective. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2001;24:246–252. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:634–641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142:1510–1518. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miwa H. Life style in persons with functional gastrointestinal disorders: large-scale internet survey of lifestyle in Japan. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:464–471. e217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang L, Toner BB, Fukudo S, et al. Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient’s perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1435–1446. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiller RC. Irritable bowel syndrome. Br Med Bull. 2005;72:15–29. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillilä MT, Färkkilä MA. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to different diagnostic criteria in a non-selected adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grundmann O, Yoon SL. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment: an update for health-care practitioners. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:691–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal A, Khan MH, Whorwell PJ. Irritable bowel syndrome in the elderly: an overlooked problem? Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:721–724. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vege SS, Locke GR, 3rd, Weaver AL, Farmer SA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders among people with sleep disturbances: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1501–1506. doi: 10.4065/79.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulewitsch MD, Enck P, Hautzinger M, Schlarb AA. Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms among German students: prevalence, characteristics, and associations to somatic complaints, sleep, quality of life, and childhood abdominal pain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:311–316. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283457b1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou HQ, Yao M, Chen GY, Ding XD, Chen YP, Li DG. Functional gastrointestinal disorders among adolescents with poor sleep: a school-based study in Shanghai, China. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:1211–1218. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roehrs T, Hyde M, Blaisdell B, Greenwald M, Roth T. Sleep loss and REM sleep loss are hyperalgesic. Sleep. 2006;29:145–151. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omagari K, Murayama T, Tanaka Y, et al. Mental, physical, dietary, and nutritional effects on irritable bowel syndrome in young Japanese women. Intern Med. 2013;52:1295–1301. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:915–922. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dowler E. Inequalities in diet and physical activity in Europe. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2B):701–709. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson L, Thelle DS, Solvoll K, Bjørneboe GE, Drevon CA. Healthy dietary habits in relation to social determinants and lifestyle factors. Br J Nutr. 1999;81:211–220. doi: 10.1017/S0007114599000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeill G, Masson L, Macdonald H, et al. Food frequency questionnaires vs diet diaries. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:884. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oellingrath I, Svendsen MV, Brantsaeter AL. Tracking of eating patterns and overweight-a follow-up study of Norwegian school children from middle childhood to early adolescence. Nutr J. 2011;10:106. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:243–249. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morcos A, Dinan T, Quigley EM. Irritable bowel syndrome: role of food in pathogenesis and management. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews SB, Waud JP, Roberts AG, Campbell AK. Systemic lactose intolerance: a new perspective on an old problem. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:167–173. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newcomer AD, McGill DB. Irritable bowel syndrome. Role of lactase deficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:339–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arvanitakis C, Chen GH, Folscroft J, Klotz AP. Lactase deficiency: a comparative study of diagnostic methods. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:1597–1602. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.10.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nanda R, James R, Smith H, Dudley CR, Jewell DP. Food intolerance and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1989;30:1099–1104. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.8.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Deng Y, Chu H, et al. Prevalence and presentation of lactose intolerance and effects on dairy product intake in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:262–268.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ligaarden SC, Lydersen S, Farup PG. Diet in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a cross-sectional study in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazzawi T, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Effects of dietary guidance on the symptoms, quality of life and habitual dietary intake of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:845–852. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1382–1390. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]