SUMMARY

In the classical anaerobic pathway of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis, that of Escherichia coli, the double bond is introduced into the growing acyl chain by the FabA dehydratase/isomerase. Another dehydratase, FabZ, functions in the chain elongation cycle. In contrast, Aerococcus viridans has only a single FabA/FabZ homolog we designate FabQ. FabQ can not only replace the function of E. coli FabZ in vivo, but it also catalyzes the isomerization required for unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Most strikingly, FabQ in combination with E. coli FabB imparts the surprising ability to bypass reduction of the trans-2-acyl-ACP intermediates of classical fatty acid synthesis. FabQ allows elongation by progressive isomerization reactions to form the polyunsaturated fatty acid, 3-hydroxy-cis-5, 7-hexadecadienoic acid, both in vitro and in vivo. FabQ therefore provides a potential pathway for bacterial synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

INTRODUCTION

Unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) biosynthesis is essential for all cells except the Archaea. UFAs (or fatty acids with similar physical properties) are required for the structure and function of cell membranes. Escherichia coli has long provided the paradigm of the type II fatty acid synthetic pathway found in bacteria, mitochondria, and plant plastids, in which each step is catalyzed by a discrete enzyme (Campbell and Cronan, 2001; Zhang and Rock, 2008). The key player in UFA synthesis in E. coli is the fabA gene encoding 3-hydroxydecanoyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) dehydratase/isomerase (Bloch, 1971; Cronan et al., 1969). This bifunctional enzyme introduces the trans-2 double bond into the growing acyl chains at the C10 level and then isomerizes this product to the cis-3 species (Bloch, 1971; Figure 1). The cis double bond is retained and following several subsequent C2 elongation cycles, the long-chain UFAs needed for membrane phospholipid function are produced (Feng and Cronan, 2009). FabB (3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase I) is also essential for UFA synthesis in E. coli and acts to channel the metabolic intermediates produced by FabA into the mainstream fatty acid synthetic pathway (Feng and Cronan, 2009; Figure 1). E. coli also contains a second 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase, FabZ, which catalyzes only the dehydration reaction of the classical fatty acid biosynthesis cycle (Heath and Rock, 1996; Mohan et al., 1994) and has only weak sequence identity (28%) with FabA. Thus, FabA plays an essential role in UFA synthesis whereas FabZ seems to function mainly in synthesis of saturated fatty acids (SFA). However, genes encoding FabA homologs are found only in the α- and γ-proteobacteria (representative bacteria would be Agrobacterium and E. coli/Salmonella, respectively) and FabA shows covariance with FabB (Feng and Cronan, 2009). Thus, other bacteria that grow anaerobically must synthesize UFAs using different enzymes. These proteins may act in pathways chemically analogous to that of E. coli, but their amino acid sequences preclude recognition as FabA/FabB homologs. Although both the FabA and FabZ monomers adopt a single “hotdog fold” in which a long central α helix is wrapped by a six-stranded antiparallel β sheet (Kimber et al., 2004; Leesong et al., 1996; White et al., 2005) and exhibit a common active-site motif, the specificity of a given protein cannot be deduced by sequence comparisons alone (White et al., 2005). The first example of this predicament was the two FabZ homologs of Enterococcus faecalis. One of these proteins (FabN) is a bifunctional dehydratase/isomerase like FabA whereas the second E. faecalis FabZ homolog has only dehydratase activity (Wang and Cronan, 2004). A different mode of UFA synthesis is found in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which encodes FabM, an isomerase that like FabA converts trans-2- decenoyl-ACP to cis-3-decenoyl-ACP but lacks dehydratase activity (Marrakchi et al., 2002). Recently an unidentified anaerobic UFA synthesis mechanism involving a gene called ufaA was reported in Neiserria gonorrhoeae (Isabella and Clark, 2011), which may require a partner (perhaps a specific electron transport chain). Anaerobic synthesis of UFAs is unique to bacteria and thus the key enzymes of this pathway, particularly FabA, have been targeted for development of new antibacterial agents (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Moynié et al., 2013).

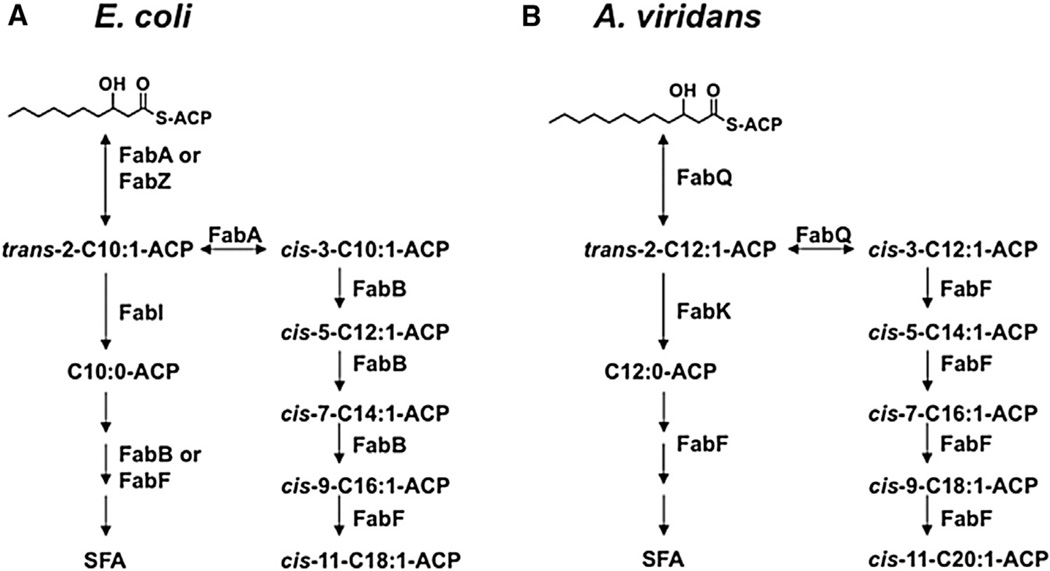

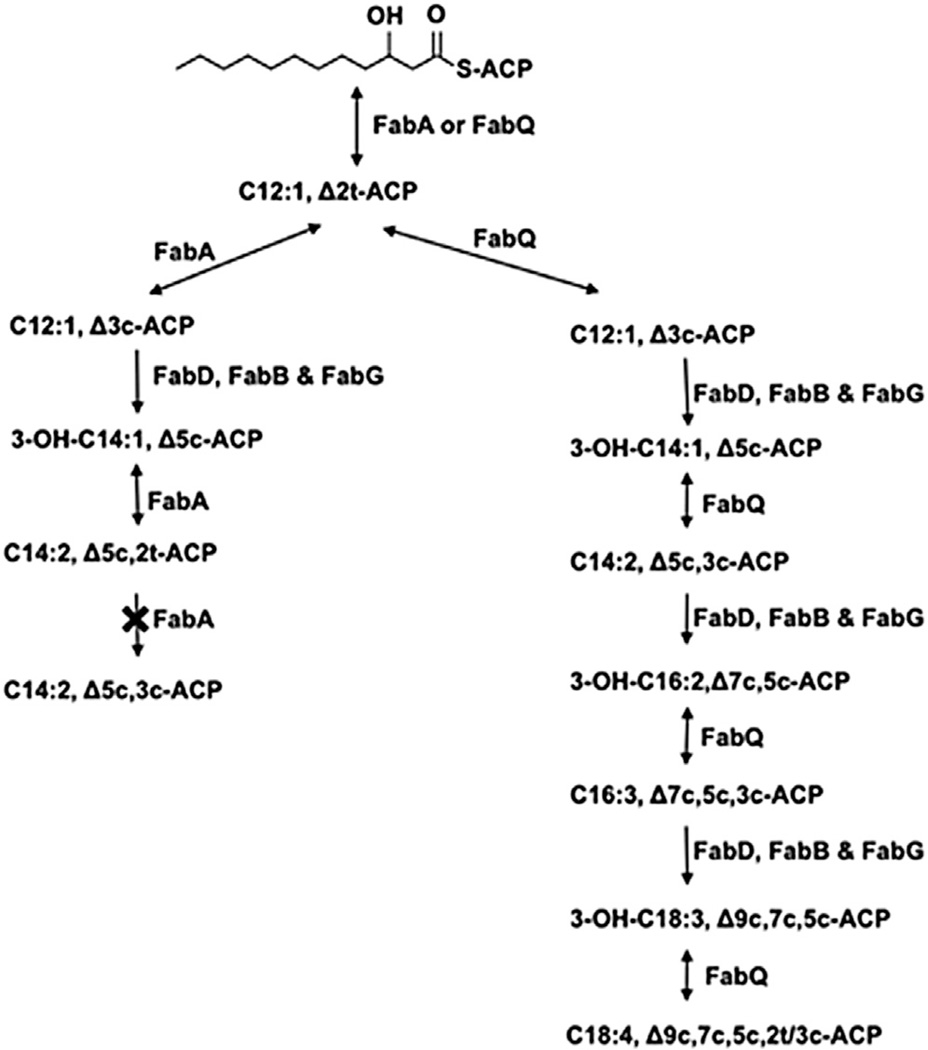

Figure 1. Comparison of the E. coli and A. viridians Fatty Acid Biosynthetic Pathways.

(A) In E. coli, the branch point between SFA/UFA synthesis occurs at the level of the ten carbon intermediate. Both FabA and FabZ can catalyze the dehydration of 3-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP to trans-2-decenoyl-ACP (Heath and Rock, 1996), whereas only FabA can isomerize the double bond to cis-3-decenoyl-ACP (Bloch, 1971; Cronan et al., 1969). SFA biosynthesis proceeds by the action of FabI on the trans-2 intermediate followed by further elongation cycles initiated by a long-chain 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase (either FabB or FabF). UFA synthesis requires FabB to elongate cis-3-decenoyl-ACP (Feng and Cronan, 2009) and thereby initiate the elongation cycles that form the major long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, C16:1Δ9c and C18:1Δ11c (Cronan and Thomas, 2009).

(B) In A. viridans, UFA synthesis proceeds from a pathway branch at the 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP stage. FabQ dehydrates 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP and isomerizes a portion of this intermediate to cis-3-dodecenoyl-ACP. FabF is required for the subsequent elongation of cis-3-dodecenoyl-ACP to produce the long-chain unsaturated fatty acids. SFA are formed by the action of the FabK enoyl-ACP reductase followed by further elongation cycles initiated by FabF.

See also Figure S2.

Aerococcus viridans is considered a saprophytic bacterium, although it can rarely cause human infections (Facklam and Elliott, 1995; Nathavitharana et al., 1983). Previous strain characterizations showed that A. viridans produces straight-chain SFAs and three unusual UFAs, cis-7-hexadecenoic acid, cis-9-octadecenoic acid, and cis-11-eicosenoic acid (Bosley et al., 1990; Moss et al., 1989). The first two acids were reported in Clostridium butyricum (now Clostridium beijerinckii), an obligate anaerobe, where they are accompanied by the typical bacterial UFAs, palmitoleate (cis-9-hexadecenoic acid) and cis-vaccenate (cis-11-octadecenoic acid) (Biebl and Spröer, 2002; Goldfine and Panos, 1971; Johnston and Goldfine, 1983; Scheuerbrandt et al., 1961).

The C. beijerinckii enzyme(s) responsible for introduction of the UFA double bonds has not been determined. However, the overall pathway was outlined by the pioneering studies of Bloch and coworkers (Scheuerbrandt et al., 1961). These workers showed that the patterns of incorporation of radioactive octanoic acid and decanoic acid into UFAs by cultures of C. beijerincki differed. This bacterium converted exogenous radioactive octanoic acid to labeled palmitoleate and cis-vaccenate, whereas radioactive decanoic acid was converted to the C16:1Δ7c and C18:1Δ9c acids (Scheuerbrandt et al., 1961). Based on this precedent and the E. coli pathway (Campbell and Cronan, 2001; Feng and Cronan, 2009), synthesis of the A. viridans UFAs was expected to involve a FabA homolog that dehydrated 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP and then isomerized the double bond to the cis-3 species (Figure 1). Thus, the reaction would proceed as does the E. coli FabA reaction except with a longer acyl chain. However, the A. viridans strains of known genome sequence contain only a single FabA/FabZ homolog and encode no recognizable homologs of FabM or UfaA. Because only a single FabZ homolog is present, a scenario similar to that of E. faecalis is ruled out. The single FabZ homolog raised the possibility that this enzyme could carry out the functions performed by both FabZ and FabA in E. coli fatty acid synthesis. If so, this would be in contrast to the situation in C. acetobutylicum, where the single FabZ homolog is unable to perform the isomerization reaction and the mechanism of double bond insertion remains unknown (Zhu et al., 2009).

We report that the single A. viridans FabZ homolog (renamed FabQ) performs the functions of both E. coli FabZ and FabA using 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP as the key substrate. Moreover, when partnered with E. coli FabB, FabQ has the extraordinary ability to bypass the need for reduction of the enoyl-ACP intermediate required in the classical fatty acid chain elongation pathway.

RESULTS

Purification and Characteristics of FabQ

The type II fatty acid biosynthetic genes in A. viridans are clustered at a single genomic location (Figure 2A). A comparison of the predicted protein sequences of these open reading frames to those of the characterized E. coli enzymes showed that the A. viridans gene cluster lacked FabA, FabI, FabB, and FabH homologs. However, the cluster includes a gene encoding a FabK flavoprotein enoyl-ACP reductase homolog expected to functionally replace FabI (Heath and Rock, 2000). The lack of FabB and FabH homologs could be explained by a trifunctional FabF, such as that of Lactococcus lactis, which functionally replaces the L. lactis FabH and both the E. coli FabB and FabF proteins (Morgan-Kiss and Cronan, 2008). However, there is only a single A. viridans FabZ homolog (renamed FabQ), which shares 39% identical residues with E. coli FabZ (Figure 2B) and no genes encoding homologs of any enzyme known to be involved in cis double bond introduction are present in the two available A. viridans genome sequences (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome). This led us to test the possibility that FabQ could functionally replace both the FabA and FabZ proteins of E. coli.

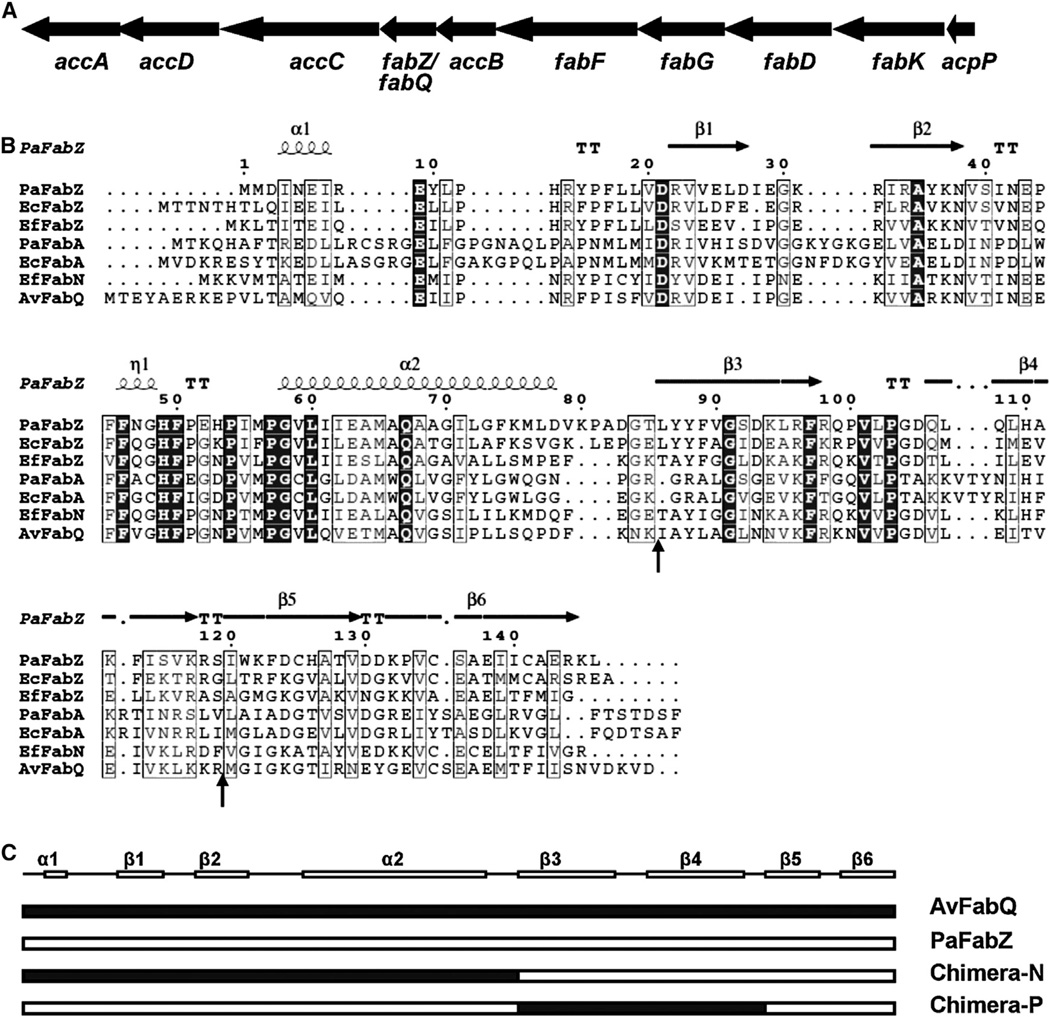

Figure 2. Organization of the A. viridans Fatty Acid Biosynthetic Gene Cluster and Alignment of A. viridans FabQ with other β-Hydroxyacyl-ACP Dehydrases.

(A) The genes of type II fatty acid biosynthesis are located in a single cluster in the A. viridans genome. The thick arrows indicate the relative sizes of the genes. The gene names below the arrows indicate the E. coli genes that correspond to the open reading frames in the A. viridans genome cluster. accA, accB, accC, and accD encode the four subunits of acetyl-CoA carboxylase; fabZ/fabQ, β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydrase; fabF, β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase II; fabG, β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase; fabD, malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase; fabK, enoyl-ACP reductase II; and acpP, ACP.

(B) Sequence alignments of FabZ/Q protein with homologs of other bacteria. The predicted protein sequence of FabZ/Q (ZP_06808097.1) from A. viridans is compared with the predicted protein sequences of PaFabZ (NP_252335.1) and PaFabA (NP_250301.1) from P. aeruginosa, EcFabZ (NP_414722.1) and EcFabA (NP_415474.1) from E. coli, EfFabZ (NP_816498.1) and EfFabN (AAO80147.1) from E. faecalis. The secondary structure diagrammed at the top is that of PaFabZ. Identical residues are in white letters with black background, similar residues are in gray letters with white background, varied residues are in black letters, and dots represent gaps. α, α-helix; β, β sheet; T, β-turns/coils.

(C) Schematic diagram of the PaFabZ/AvFabQ chimeric proteins constructed. Chimeras were constructed based on the secondary structure predictions illustrated in B and the junctions are indicated by the arrows of (B).

See also Figure S5.

We first expressed FabQ in E. coli and compared the purified enzyme to the well-studied E. coli FabA plus the Pseudomonas aeruginosa FabZ and FabA proteins. The N terminal hexahistidine-tagged FabQ protein was expressed in E. coli and purified by affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography. The purified protein had an apparent monomeric molecular mass of ~18 kDa based on SDS-gel electrophoresis. The size exclusion chromatographic elution profile of FabQ (Figure S1 available online) indicated that the FabQ is a hexamer in solution form as are the FabZ proteins of E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Kimber et al., 2004), whereas the E. coli and P. aeruginosa FabA proteins are dimeric both in solution (Kass et al., 1967; Kimber et al., 2004) and in crystals (Leesong et al., 1996; Moynié et al., 2013).

Heterologous Complementation of E. coli fabZ and fabA Null Mutant Strains by Expression of FabQ

The function of FabQ in heterologous complementation assays was tested in parallel using two E. coli mutant strains, HW7 and HW8 (Wang and Cronan, 2004). In strain HW7, the chromosomal fabZ gene was disrupted by insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette and the strain remains viable due to the presence of a plasmid that encodes Clostridium acetobutylicum FabZ under control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. Because fabZ is an essential gene in E. coli (Baba et al., 2006), this strain grows in the presence of arabinose but fails to grow in the absence of arabinose or in the presence of the antiinducer, fucose (Figure 3A). Strain HW8 is a derivative of the fabA null mutant strain MH121, which also carries a null mutation in cfa, so that unsaturated fatty acids cannot be converted to their cyclopropane derivatives. The fabQ gene was inserted into an IPTG-inducible vector. This plasmid was introduced into E. coli strains HW7 and HW8 and the resulting transformants were tested for growth following induction of FabQ expression. No growth of strain HW8 transformants was found in the absence of oleic acid supplementation (Figure S4A). However, we found that strain HW7 transformed with fabQ grew in the presence of IPTG and fucose, indicating that FabQ expression restored β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase function, albeit less efficiently than the wild-type E. coli FabZ (Figure 3A). Hence, FabQ functionally replaced E. coli FabZ.

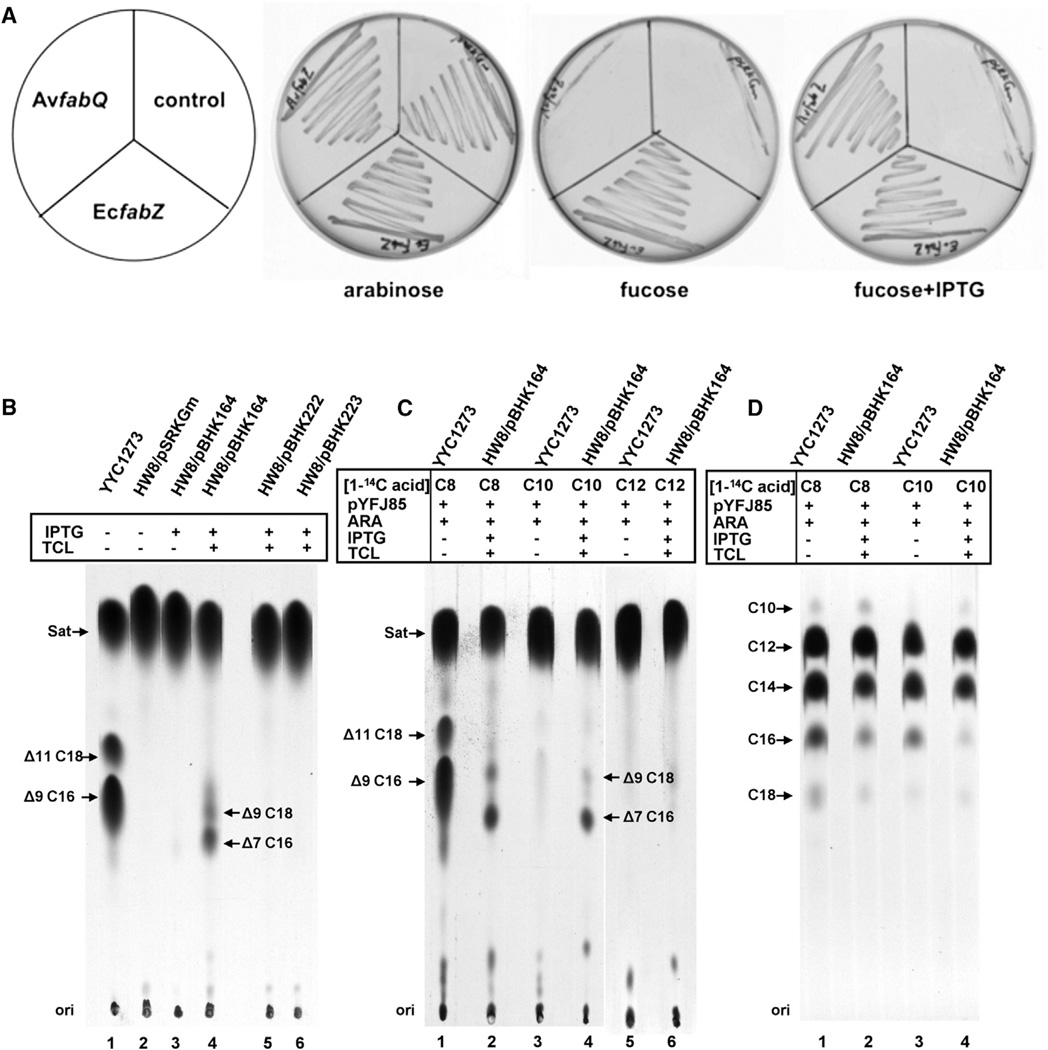

Figure 3. In Vivo Activity of A. viridans fabQ.

(A) Complementation of arabinose-dependent growth of an E. coli strain HW7 by a plasmid expressing A. viridans fabQ. The fabQ and E. coli fabZ genes were inserted into the lac promoter expression vector pSRKGm resulting in pBHK164 and pBHK172, respectively. These plasmids were then transformed into E. coli HW7, a strain in which the chromosomal fabZ gene is deleted and FabZ function is provided by a compatible plasmid carrying C. acetobutylicium fabZ under control of the vector arabinose (pBAD) promoter. The plates contained RB medium with arabinose as the inducer of fabZ expression (or the anti-inducer fucose) or with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to induce fabQ or fabZ expression. The plates were incubated overnight at 30°C due to temperature-sensitive λ prophage carried by the host strain. Strain HW7 carrying the empty vector, pRKGm, was used as a negative control.

(B–D) Incorporation of [1-14C]acetate or medium chain length [1-14C]-labeled fatty acids into the membrane phospholipids of the wild-type E. coli strain YYC1273 or the E. coli fabA strain HW8 transformed with the empty vector pSRKGm, plasmid pBHK164 encoding A. viridans fabQ, plasmid pBHK222 encoding chimera-X-N, or pBHK223 encoding chimera-X-P (Figure 2). (B) Argentation TLC analysis of [1-14C]acetate-labeled E. coli fabA strain HW8 transformed with the A. viridans fabQ. (C) Argentation TLC analysis of [1-114C]-labeled octanoate-, decanoate-, or dodecanoate-labeled E. coli fabA strain HW8 transformed with A. viridans fabQ. All strains carried the AasS-encoding plasmid pYFJ85 to allow the conversion of the exogenous acids to the ACP thioesters required to enter the fatty acid synthetic pathway. (D) The saturated fatty acid methyl ester fraction obtained by argentation column chromatography was analyzed with reverse-phase TLC (see the Experimental Procedures). Arabinose (ARA) was present at a concentration of 0.02% and IPTG at a concentration of 0.5 mM. Triclosan (TCL) was added at 0.1 µg/ml to inhibit host FabI activity. Sat, SFA esters.

See also Figures S2 and S4 and Tables S1 and S2.

FabQ Has FabA Activity In Vivo

Although fabQ failed to allow growth of the E. coli fabA strain, it remained possible that the recombinant plasmid supported UFA synthesis, but that the levels of UFA synthesized were insufficient for growth. This possibility was tested by [1-14C]acetate labeling of the fatty acids synthesized by strain HW8 carrying the fabQ plasmid followed by analysis of the resulting radioactive fatty acids for UFA. Upon IPTG induction, no UFA synthesis was detected (Figure 3B). A plausible explanation for the observed lack of UFA synthesis was that FabI, the E. coli enoyl-ACP reductase, converted the trans-2-enoyl-ACP intermediate to acyl-ACP before the putative FabQ isomerization activity could act. Thus, the labeling experiment was repeated in the presence of a low dose of triclosan, a specific inhibitor of FabI (Campbell and Cronan, 2001; White et al., 2005) to allow the putative isomerase activity an opportunity to compete for the trans-2-enoyl-ACP intermediate. Upon addition of triclosan, UFA synthesis was readily detected in strain HW8 expressing FabQ and the UFAs synthesized had the double bond positions characteristic of A. viridans (Bosley et al., 1990; Moss et al., 1989), as judged from argentation chromatography (Figure 3B). In the FabQ-expressing cultures, the UFA methyl ester species migrated as cis-7 and cis-9 UFAs in place of the cis-9 and cis-11 species normally found in E. coli (Figure 3B). In the presence of triclosan, expression of FabQ in the fabA mutant HW8 restored UFA synthesis, albeit with low efficiency (11% as much UFA as the wild-type strain; Table S2), but gave sufficient material for identification of the double-bond positions and chain lengths of the UFAs by analysis of their dimethyldisulphide adducts. Mass spectral analyses of the dimethyldisulfide adducts of these esters identified the two UFAs as cis-7-hexadecenoic and cis-9-octadecenoic acids (Figure S2) in accord with the argentation chromatography results (Figures 3B and 3C). Note that we did not observe cis-11-eicosenoic acid, a major A. viridans UFA. Because E. coli accumulates C20 fatty acids in the absence of phospholipid synthesis (Cronan et al., 1975), the lack of this acid can be attributed to the specificities of the acyltransferases of E. coli phospholipid synthesis.

Based on the classical pathway of anaerobic UFA synthesis (Bloch, 1971; Scheuerbrandt et al., 1961) we expected that the synthesis of the C16:1Δ7c and C18:1Δ9c UFAs begins by dehydration of 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP (Figure 1). This expectation was tested by expression of Vibrio harveyi acyl-ACP synthetase (AasS) to allow exogenous fatty acids to enter the E. coli fatty acid synthetic pathway (Jiang et al., 2010). Hence, the chain length dependence of the branch point between UFA and SFA could be directly tested in vivo as in the classical studies of Bloch and coworkers (Bloch, 1971; Scheuerbrandt et al., 1961). The pathway predicted that upon expression of FabQ and AasS, exogenously added 14C-labeled octanoic and decanoic acids would be incorporated into UFAs as well as SFAs whereas [1-14C]dodecanoic acid would label only SFAs. In contrast, the E. coli pathway would convert octanoic acid to both UFA and SFA, whereas decanoic and dodecanoic acids would give only SFAs. These labeling patterns were as predicted (Figure 3C), and thus the FabQ substrate should be 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP. Note that the use of carboxyl-labeled precursor fatty acids eliminated the possibility of shortening of the acids by β-oxidation prior to incorporation. Finally, reverse-phase thin-layer chromatography (TLC) showed that the labeled acids were similarly elongated to long-chain phospholipid SFAs (Figure 3D).

FabQ Has FabA Activity In Vitro, but Unlike FabA, Dehydrates and Isomerizes Unsaturated 3-Hydroxy Substrates

FabQ was tested for its ability to replace FabA in a reconstituted fatty acid synthesis system with 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP as substrate. The defined in vitro synthesis system was assembled from purified E. coli proteins and allowed direct comparison of the activities of FabA, FabZ, and FabQ. In the FabZ-containing reaction, 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP was converted to trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP as expected from prior work (Heath and Rock, 1996; Figure 4A, lane 7). When FabA, FabD, FabB, and FabG were added, the elongation product formed, 3-hydroxy-cis- 5-tetradecenoyl-ACP, was the product of FabA-catalyzed isomerization of trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP to cis-3-dodecenoyl-ACP and the elongation of the cis product by FabB (Figure 4A, lane 8). The addition of only FabQ also resulted in conversion of 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP (Figure 4A, lane 2).

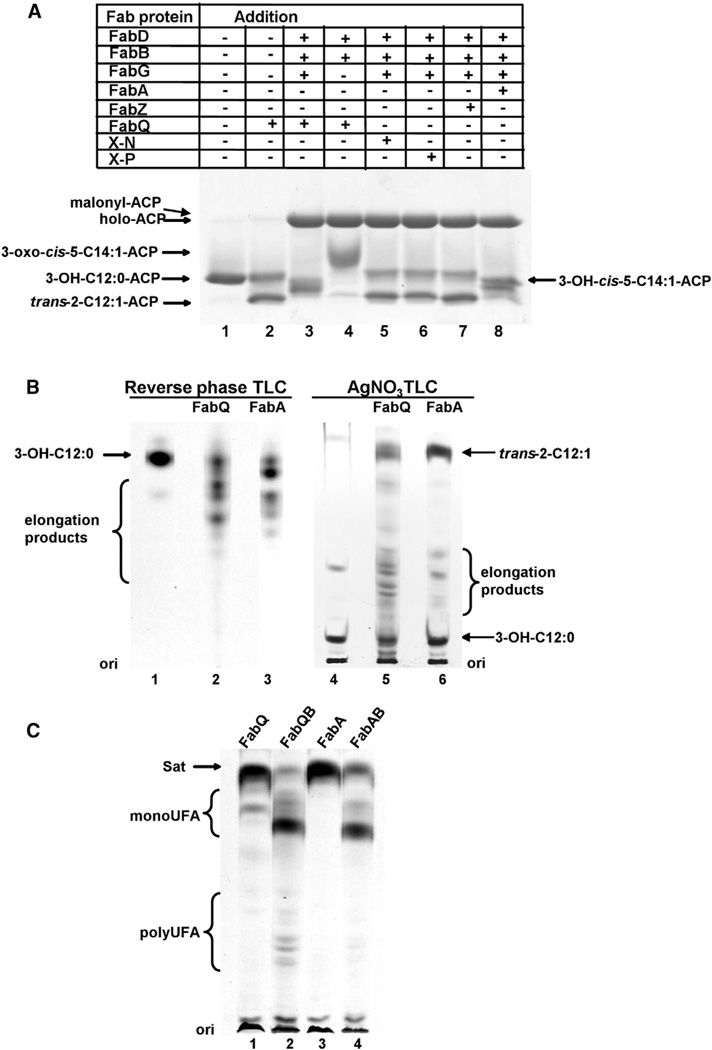

Figure 4. FabQ Catalyzes the Formation of Polyunsaturated Acyl-ACP Intermediates In Vitro and In Vivo.

(A) The catalytic properties of FabQ were tested in a reconstituted in vitro E. coli fatty acid synthesis system with 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP (3-OH-C12: 0-ACP) as the substrate. The reaction mixture is described in the Experimental Procedures. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, and the reaction products were resolved by conformationally sensitive gel electrophoresis on 18% polyacrylamide gels containing an optimized urea concentration (Cronan et al., 1988; Cronan and Thomas, 2009; Post-Beittenmiller et al., 1991). The appearance of elongation products in lanes 3 and 8 indicates that trans-2-C12:1-ACP was isomerized to cis-3-C12:1-ACP, which allowed elongation by FabB.

(B) Fatty acid products formed in vitro. 14C-labeled 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP was obtained using the reconstituted fatty acid synthesis system (see the Experimental Procedures). Then either FabQ or FabA was added to the reaction mixtures, respectively, followed by incubation at 37°C for additional 60 min. The synthesized acyl chains were then converted to their methyl esters and separated by either reverse phase or argentation TLC with detection by autoradiography.

(C) Fatty acid products formed in vivo by analysis of [1-14C]acetate-labeled esters present in the medium of E. coli fabA strain HW8 transformed with plasmids expressing both E. coli ′TesA and the enzymes denoted. Cultures of plasmid-containing strains were grown and the fatty acid methyl esters were obtained from the medium as described in the Experimental Procedures. The methyl esters were then separated by argentation TLC followed by autoradiography.

See also Figures S1 and S3 and Table S1.

Upon replacement of FabA with FabQ in reactions containing FabD, FabB, and FabG, we expected the same products as those formed with FabA. However, gel electrophoresis showed a broader band of greater mobility, suggesting that several products were present (Figure 4A, lane 3). Provisional identification of the ACP thioester intermediates formed in these reconstitution assays was done by mass spectrometry. Note that the small amounts of the products precluded rigorous determination of the exact structures of the acyl chains (e.g., the positions and conformations of double bonds). The control reaction of Figure 4A (lane 2), in which only FabQ was present, contained 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP and trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP as expected (mass peaks at 9,046.8 and 9,029.1, respectively; Figure 5A), whereas the mass peaks for the holo-ACP starting material and the malonyl-ACP formed by FabD occurred at 8,847.8 and 8,933.7, respectively (Figure 5B). When FabA, FabD, FabB, and FabG were all present, the elongation products formed had the masses of the ACP thioesters of 3-hydroxy, cis-5-tetradecenoyl-ACP (3-OH-C14:1, Δ5c-ACP; mass 9,072.1) and 5-cis, 2-trans-tetradecadienoyl-ACP (C14:2, 5c, 2t-ACP; mass 9,054.6; Figure 5C) in accord with previous results (Heath and Rock, 1996). Unexpectedly, when FabQ replaced FabA, the elongation products formed had the masses of a C16 acyl-ACP containing three double bonds (9,080.3), a 3-hydroxy-C16 acyl-ACP containing two double bonds (9,098.6), and a C18 acyl-ACP containing four double bonds (9,106.6; Figure 5B). Therefore, in the absence of FabI, FabQ appeared to have dehydrated 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP and catalyzed its isomerization to cis-3-dodecenoyl-ACP (Figure 7). This in turn was elongated by FabB to give 3-oxo-cis-5-tetradecenoyl-ACP. The oxo group of this product would be reduced by FabG to produce an FabQ substrate that was dehydrated to trans-2 (cis-3), cis-5-tetradecadienoyl-ACP as is the case with FabA. FabB would then elongate the isomerization product cis-3, 5-tetradecadienoyl-ACP to 3-oxo-cis-5,7-hexadecadienoyl-ACP, and FabG action would allow another cycle of dehydration, isomerization, and elongation to produce a C18 acyl-ACP containing four double bonds (Figure 7). As expected, formation of these products required FabQ, FabB, FabG, and FabD (Figure 4A). Elongation of 3-hydroxydodecanoyl- ACP was also demonstrated by use of [2-14C]malonyl-CoA and reverse-phase TLC, which separates fatty acid esters according to their hydrophobicity (hence by chain length and degree of unsaturation with a double bond canceling about two methylene groups; Christie, 2003). As shown in Figure 4B, several species formed in FabQ reactions were more hydrophobic than any formed in FabA reactions. The presence of several double bonds was shown by the very slow migration of the methyl esters on AgNO3 chromatography (Metz et al., 2001; Morris and Wharry, 1965; Figure 4B). Therefore, FabQ acts like FabA in UFA synthesis, but following dehydration of 3-hydroxy substrates that contain a double bond, it isomerizes the trans double bond to the cis configuration, a reaction that FabA cannot catalyze (Heath and Rock, 1996). As mentioned previously, these acids were not produced in vivo unless the FabI enoyl-ACP reductase was inhibited because FabI competes with FabQ for enoyl-ACP derivatives and reduces the trans-2 double bonds (Figures 3B and 3C). FabI similarly outcompetes FabQ in vitro (Figure S3).

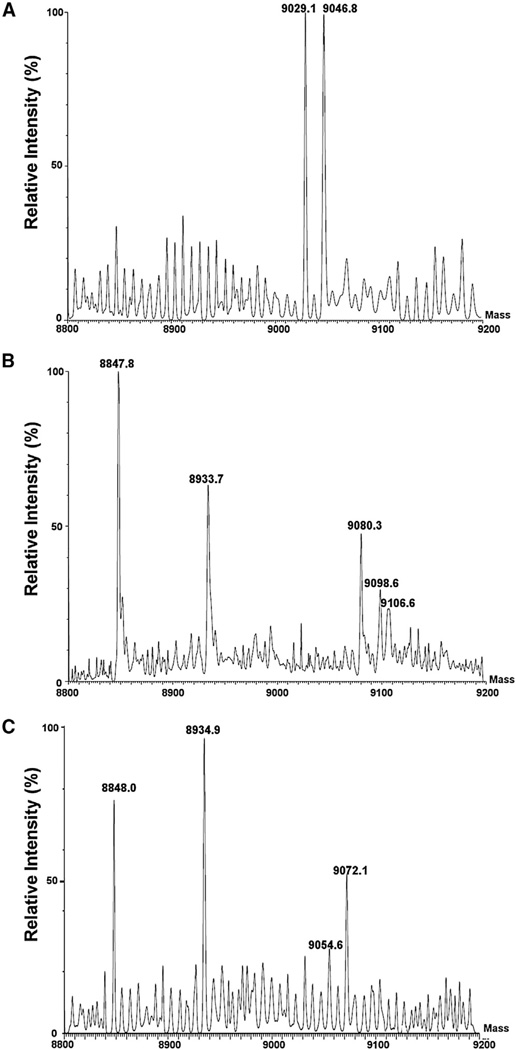

Figure 5. Mass Spectrometry of Products of the FabQ and FabA-Catalyzed Reactions In Vitro.

(A) Mass spectrum of the reaction products of lane 2 of Figure 4A shows dehydration of 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP (9,046.8) to trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP (mass 9,029.1).

(B) Mass spectrum of the products of the reaction mixture of lane 3 of Figure 4A showing the FabQ-catalyzed conversion of 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to a series of unsaturated acyl-ACPs putatively assigned as C16:3, Δ7c, Δ5c, Δ2t/3c-ACP (mass 9,080.3); 3-hydroxy-C16:2, Δ7c, Δ5c-ACP (mass 9,098.6); and C18:4, Δ9c, Δ7c, Δ5c, Δ2t/3c-ACP (mass 9,106.6). The peaks of masses 8,847.8 and 8,933.7 are holo-ACP and malonyl-ACP, respectively.

(C) Mass spectrum of the products of the reaction mixture in lane 8 of Figure 4A showing the FabA-catalyzed conversion of 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to an acyl-ACP putatively assigned as 3-hydroxy, cis-5-tetradecenoyl-ACP (3-OHC14: 1, Δ5c-ACP; mass 9,072.1) and 5-cis, 2-trans-tetradecadienoyl-ACP (C14:2, 5c, 2t-ACP; mass 9,054.6) based on the work of Heath and Rock (Heath and Rock, 1996). The mass peaks at 8,848.0 and 8,934.9 are those of holo-ACP and malonyl-ACP, respectively.

See also Table S1.

Figure 7. Proposed Pathway for Enoyl-ACP Reductase-Independent Chain Elongation by FabQ plus E. coli FabB.

Production of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids In Vivo by Coexpression of FabQ and FabB

To confirm the polyunsaturated fatty acids formed in vitro, plasmid pHC122, which expresses the broad chain length specificity E. coli thioesterase I lacking its periplasmic export sequence (′TesA; Cho and Cronan, 1993), was transformed into E. coli strain HW8. Expression of ′TesA results in hydrolysis of the acyl-ACP thioester bonds and allows export of the liberated fatty acids into the culture medium. Use of this strategy avoids the necessity that abnormal fatty acids be incorporated into phospholipids (Cho and Cronan, 1993; Feng and Cronan, 2009). Individual colonies of strains carrying plasmid pHC122 and compatible plasmids that expressed FabQ, FabA, FabQ plus FabB or FabA plus FabB were grown in the presence of [1-14C]acetate and triclosan followed by induction with protein expression. The medium was collected followed by extraction of the free fatty acids. The fatty acids were converted to their methyl esters and analyzed by argentation TLC (Figure 4C). We found that only upon coexpression of FabQ and FabB did the medium contain detectable levels of poly-UFAs, whereas expression of FabQ or FabA in the absence of FabB overexpression gave the expected high-level production of saturated fatty acids (Figure 4C).

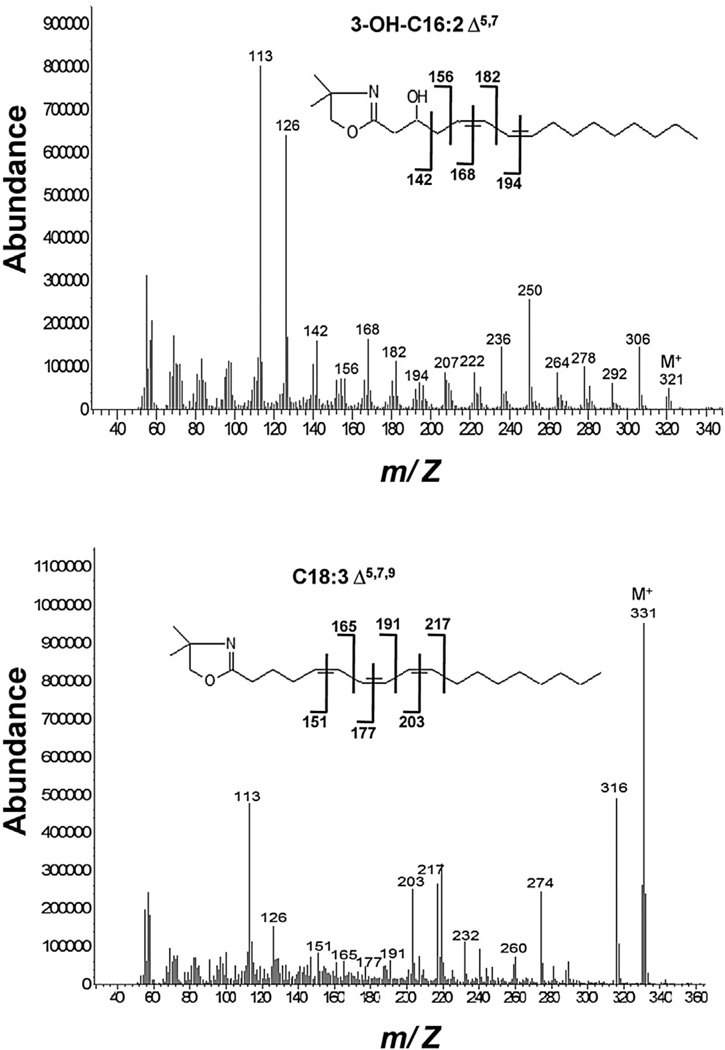

To determine the positions of double bonds of these poly-UFAs, E. coli strain HW8 carrying the plasmids pHC122 and pBHK265 was grown as above but in nonradioactive medium, and large volumes of culture supernatant were subjected to free fatty acid extraction because of the low levels of fatty acids produced. Because the mass spectra of fatty acid methyl esters do not contain characteristic ion fragments that allow location of double-bond positions and dimethyldisulfide addition to proximal double bonds gives complex and poorly volatile products, the positions of the double bonds were identified based on gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis of 4,4-dimethyloxazoline (DMOX) derivatives. The nitrogen atom of the derivatives carries the charge during ionization resulting in radical-induced cleavage at every carbon-carbon bond along the alkyl chain. If a double bond occurs between carbon n and n + 1, a gap of 12 atomic mass units (amu) between ions corresponding to fragments containing n − 1 and n carbons is observed (Qi et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 1988). In saturated segments of the chain, the gaps of 14 amu are seen due to cleavage between adjacent methylene groups. We found only one poly-UFA in the culture medium of strain HW8 expressing FabA plus FabB, the trans-2, cis-5 species of Figure 5C and Heath and Rock (Heath and Rock, 1996), whereas longer chain acids were found when both FabQ and FabB were expressed from compatible plasmids (Figure 6). The mass spectra of the DMOX derivatives of 3-hydroxy-C16:2 and a probable C18:3 species extracted from the culture medium of strain HW8 expressing FabQ plus FabB were obtained. For the former acid, a peak at m/z 142 characteristic of a hydroxyl group at position 3 was present. Gaps of 12 amu between m/z 156 and 168 and between m/z 182 and 194 indicate double bonds at the 5 and 7 positions. When combined with the molecular ion at m/z 321, the acid was identified as 3-hydroxy-C16:2, Δ7, Δ5. We also putatively identified the other poly-UFA as C18:3 based on the highly abundant molecular ion at m/z 331. Indeed, the presence of the m/z 217 ion in the DMOX derivative mass spectrum suggested that all the three double bonds are located between the carboxyl and carbon 10. Gaps of 12 amu between m/z 165 and 177 and between m/z 191 and 203 strongly suggested that double bonds are present in the 7 and 9 positions. Thus, this acid is likely to be C18:3, Δ9, Δ7, Δ5. Although this C18:3 isomer was unexpected, it can be readily explained by reduction of the trans-2 double bond of the C18:4, Δ9, Δ7, Δ5, trans-Δ2 intermediate by residual FabI activity, consistent with the in vitro product (Figure 5B). We also found trace amounts of the C16:3 and C18:4 species having molecular ions at m/z 303 and m/z 329, respectively, as expected from the in vitro results. However, the DMOX derivative mass spectra obtained for these acids were complex, and we were unable to determine the double-bond positions.

Figure 6. Positional Analysis of the Carbon Double Bonds of Two Poly-UFAs Extracted from the Culture Medium of Strain HW8 Expressing FabQ Plus FabB with Partial Inhibition of FabI Activity.

See also Table S1.

Domain Swapping between FabQ and FabZ

Previous domain-swapping experiments showed that the isomerase activity of FabN was caused by the structure of the β sheets controlling the shape of the active site tunnel (White et al., 2005). To test if it is the case for FabQ, two chimeric FabQ/FabZ proteins (Figure 2C) were tested to see if the minimal structural elements (the β3 and β4 strands) were sufficient to transform P. aeruginosa FabZ from a dehydratase into a dehydratase/isomerase. Chimera-N containing the N-terminal part of FabQ was constructed as a negative control, whereas chimera-P containing the β3 and β4 strands of FabQ was expected to show isomerase activity. Both proteins retained only dehydratase activity as indicated by the formation of trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP in vitro and no elongation products were observed (Figure 4A, lanes 5 and 6). Expression of the chimeric proteins also partially restored the growth of strain HW7 (Figure S4B), and thus weak FabZ activity was retained. Moreover, in vivo, only 14C-labeled SFAs were synthesized in the presence of triclosan (Figure 3B). Thus, the β strands of the dimer interface are not sufficient to impart isomerase activity.

Bioinformatic Analysis of FabQ

The phylogeny of FabQ was determined in relation to other members of FabZ or FabM homologs (Figure S5). Members from the related 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratases HadABC were included as an out-group. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that FabQ homologs form a clade distinct from other groups. Close homologs of FabQ are found in the order Lactobacillales. Three FabZ homologs from C. maltaromaticum, G. adiacens, and D. pigrum showed the highest sequence identity (64%) with FabQ. All sequenced strains of these species encode only one FabZ homolog and lack known UFA synthetic genes.

DISCUSSION

FabQ was shown to be responsible for the synthesis of C16:1Δ7c and C18:1Δ9c, two major UFAs of A. viridans with 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP as the key precursor. Thus, the UFA biosynthetic pathway in A. viridans branches from the classic fatty acid biosynthesis pathway by “tapping off” the 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP intermediate (Figure 1) rather than the 3-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP as in E. coli and many other bacteria. FabQ can act strictly as a dehydratase like E. coli FabZ or as a dual-function dehydratase/isomerase like E. coli FabA. This is a FabZ homolog that must act in a bifunctional manner. The ratio of activities is such that in vitro FabQ allows the elongation of acyl chains in the absence of an enoyl-ACP reductase such as E. coli FabI. In vitro, long-chain products are made from 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP by the combined action of FabQ, FabB, FabG, and FabD. The poly-UFA, 3-hydroxy-cis-5, 7-hexadecadienoic acid, was detected in vivo upon coexpression of FabQ and FabB when FabI was partially inhibited. We believe these products are formed by the following sequence of reactions (Figure 7). FabQ dehydrates 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP to trans-2-acyl-ACP and then isomerizes the double bond to the cis-3-isomer. In our model (Figure 7), movement of the double bond from position 2 to position 3 allows FabB to elongate cis-3-dodecenoyl-ACP to produce 3-oxo-cis-5-tetradecenoyl-ACP, which is reduced to 3-hydroxy-cis-5-tetradecenoyl-ACP by FabG to provide a different FabQ substrate. Another round of this atypical elongation cycle will give 3-hydroxy-cis-5, 7-hexadecadienoyl- ACP and a further round will give 3-hydroxy-cis-5, 7, 9-octadecatrienoyl-ACP. Heath and Rock (Heath and Rock, 1996) reported that in the absence of an enoyl-ACP reductase and in the presence of FabB, FabG, and FabA, their in vitro system elongated cis-3-decenoyl-ACP to a mixture of 3-hydroxy, cis-5-dodecenoyl-ACP and trans-2, cis-5-dodecdienoyl-ACP, but no further elongation can occur because FabA is unable to isomerize the trans-2 double bond to the cis-3 species required for elongation by FabB. The inability of FabA to isomerize the C12 unsaturated species can probably be attributed to the very tight hydrophobic tunnel where FabA sequesters the substrate acyl chain (Leesong et al., 1996; Moynié et al., 2013). Modeling done similar to that of Moynié and coworkers (Moynié et al., 2013) suggests that the kinks introduced by the double bond could clash with the wall of the tunnel, resulting in distorted substrate presentation or perhaps an inability to bind the substrate. This scenario seems unlikely to explain isomerization by FabQ because within its active site tunnel the enzyme readily tolerates double bonds, which would alter any strict geometry required. Thus we expect FabQ to have a larger or more flexible acyl chain-binding tunnel such as that of P. aeruginosa FabZ (White et al., 2005). Hence, when available, the FabQ structure should be most instructive in further interpretations of the FabA and FabZ structures.

The FabQ isomerase activity directly competes with enoyl-ACP reductase for the common substrate, trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP, indicating that trans-2-dodecenoyl-ACP does not remain tightly bound to the enzyme. The same is true of FabA where free trans-2-decenoyl-ACP has been demonstrated in vitro (Guerra and Browse, 1990). Moreover, overexpression of FabA in E. coli results in increased synthesis of saturated fatty acids (Clark et al., 1983). This is because FabB activity becomes limiting and FabI reduces the “backed up” trans-2-decenoyl-ACP. It follows that in A. viridans the ratio of the activities of FabQ and enoyl-ACP reductase must be coordinated in order that the proportions of UFA and SFA producing functional phospholipids maintained. The ratio of the two enzyme activities seems likely to be “hard wired” because both FabQ and FabK (the putative enoyl-ACP reductase) appear to be cotranscribed within a fatty acid synthesis operon (Figure 2A). The A. viridans fatty acid synthesis pathway we propose requires that the single FabF encoded by this bacterium must be able to perform the key reaction catalyzed by E. coli FabB, elongation of the cis-3-acyl-ACP resulting from the FabQ isomerization reaction. The single FabFs encoded by both Lactococcus lactis (Morgan-Kiss and Cronan, 2008) and Clostridium acetobutylicium (Zhu et al., 2009) have this ability and show strong sequence (49%–59%) identity to A. viridans FabF, particularly in the regions implicated in acyl chain substrate binding (White et al., 2005). Why does A. viridans encode only a single FabZ/FabA homolog whereas other bacteria have multiple homologs? One possibility is the small genome (2.01 Mb) of this bacterium. It is 60% smaller than the E. faecalis genome, which encodes two FabZ/FabA homologs. Moreover, two other bacteria encoding FabQ homologs have similarly small genomes (Figure S5).

The enoyl-ACP reductase-independent elongation pathway we postulate (Figure 7) has parallels in the bacterial synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids by certain type I polyketide synthases called polyunsaturated fatty acid synthases (Jiang et al., 2008; Metz et al., 2001; Orikasa et al., 2009). These poly-functional protein systems all contain dehydratase domains that strongly resemble E. coli FabA and some also have FabZ-like domains (Orikasa et al., 2009). The elongation pathway proposed for the early steps of eicosapentaenoic acid synthesis is the same as our elongation pathway except that the pathway begins with 3-hydroxyhexanoate (Metz et al., 2001). Hence, some of these dehydratase domains may well have enzymatic properties resembling those of FabQ.

It may be possible to use FabQ to bypass enoyl-ACP reductase activity in a bacterium that does not require saturated fatty acids for growth. We previously showed that L. lactis grows well with only unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (Lai and Cronan, 2003; Morgan-Kiss and Cronan, 2008); thus, the unusual FabQ-dependent poly-UFAs might suffice to support growth of an enoyl-ACP reductase null mutant of this bacterium. If successful, this would provide for feasible production of a new class of conjugated polyunsaturated fatty acids.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Oligonucleotides

Materials

The growth media and growth conditions are given in Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Table S1. Fatty acid synthetic proteins were expressed, purified, analyzed, and utilized as given in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Acyl-ACP Preparations

3-Hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP was synthesized as described previously (Bi et al., 2012). Briefly, a typical reaction mixture consists of 25 µM holo-ACP, 200 µM fatty acid, and 170 nM V. harveyi AasS in a buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, and 10 mM ATP in a reaction volume of 1 ml. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 4 hr, stopped by the addition of two volumes of acetone, and the proteins were allowed to precipitate at −20°C overnight. The precipitates were pelleted at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and then washed twice with three volumes of acetone. The pellets were air-dried and resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM tris[2-carboxyethyl] phosphine (TCEP). The final samples were concentrated with an Amicon ultracentrifugation filter device from Millipore (5,000 MWCO). Acyl-ACP synthesis was verified by electrophoresis on 18% gels containing 2.5 M urea (Cronan and Thomas, 2009; Jiang et al., 2008) and by electrospray mass spectrometry. Note that the ACP preparation retained the N-terminal methionine.

Assay of FabQ Activity In Vitro

Fatty acid synthesis was reconstituted in vitro to assay FabQ activity using the purified enzymes that catalyze the fatty acid biosynthesis essentially. The fatty acid synthesis assay mixtures contained, in a volume of 30 µl, 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.0); 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol; 25 µM 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP; 100 µM NADPH; 0.2 µg each of FabD, FabB, and FabG; 75 µM holo-ACP; and 150 µM malonyl-CoA. FabQ (0.2 µg), chimeric enzymes (0.2 µg), FabA (0.2 µg), or FabZ (0.2 µg) was added to the appropriate reactions as indicated in the figure legends. For the competition of FabI and FabQ, different amounts (0.02, 0.2, 1, and 4 µg) of EcFabI and 100 µM NAPH were also added to the reactions above. Note that the substrate 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP was added last to ensure simultaneous attack of AvFabQ and EcFabI for the substrates. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reactions were stopped by placing the tubes in ice slush. Samples of the mixtures were mixed with gel loading buffer and analyzed with conformationally sensitive gel electrophoresis on 18% polyacrylamide gels containing a concentration of urea optimized for the separation (Cronan and Thomas, 2009; Post-Beittenmiller et al., 1991).

To produce 14C-labeled 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-ACP, the fatty acid synthesis assay mixtures, which contained 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 25 mM decanoyl-ACP, 100 mM NADPH, 100 mM holo-ACP, and 100 mM [2-14C]malonyl-CoA (specific activity, 55 mCi mmol−1), EcFabD (1 µg), EcFabB (1 µg), and EcFabG (1 µg) in a final volume of 100 µl, were incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Then either 1 µg AvFabQ or EcFabA was added to the reaction mixtures, respectively, followed by incubation at 37°C for additional 60 min. The assay mixtures were dried by nitrogen, and the acyl chains of in vitro products were then converted to their methyl esters by sodium methoxide in methanol, which were separated by argentation TLC or reverse-phase TLC and detected by autoradiography as described previously (Jiang et al., 2010). For high-resolution separation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by argentation TLC, toluene-acetonitrile (98.5:1.5, v/v) was used as the developing solvent (Wilson and Sargent, 1992).

Radioactive Labeling, Phospholipid Extraction, and Fatty Acid Analyses

Detailed protocols are given in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Mass spectrometry of proteins and isolated fatty acid moieties and their modified species are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Fatty acid synthesis is essential in all organisms except the Archea and the fatty acid biosynthetic reactions are strictly conserved. Fatty acid synthesis is required not only for synthesis of membrane lipids, but also for protein acylation and synthesis of the key vitamins biotin and lipoic acid. Fatty acids are assembled by incorporating carbons atoms two at a time by an elongation cycle that requires three enzymes that act after attachment of the two carbons to the growing fatty acid chain. These reactions prepare the chain for entry into the next elongation cycle. The last of these reactions involves removal of a double bond by reduction and is catalyzed by an enzyme called enoyl-ACP reductase. We report FabQ, an enzyme from the bacterium Aerococcus viridans, which can bypass the completely conserved enoyl-ACP reductase step by flipping the double bond down the chain to allow elongation to proceed without reduction, thereby resulting in synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids. FabQ is also able to catalyze both the strict dehydratase and dehydratase/isomerase fatty acid synthetic reactions generally performed by two different enzymes in other bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI15650 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. We thank Dr. Peter Yau and Dr. Alexander Ulanov of the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center and Dr. Furong Sun and Elizabeth Eves of the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for help with protein identification and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, five figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.07.007.

REFERENCES

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:2006. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi H, Christensen QH, Feng Y, Wang H, Cronan JE. The Burkholderia cenocepacia BDSF quorum sensing fatty acid is synthesized by a bifunctional crotonase homologue having both dehydratase and thioesterase activities. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;83:840–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biebl H, Spröer C. Taxonomy of the glycerol fermenting clostridia and description of Clostridium diolis sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2002;25:491–497. doi: 10.1078/07232020260517616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch K. β-hydroxydecanoyl thioester dehydrase. In: Boyer PD, editor. The Enzymes. New York: Academic Press; 1971. pp. 441–464. [Google Scholar]

- Bosley GS, Wallace PL, Moss CW, Steigerwalt AG, Brenner DJ, Swenson JM, Hebert GA, Facklam RR. Phenotypic characterization, cellular fatty acid composition, and DNA relatedness of aerococci and comparison to related genera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:416–421. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.416-421.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JW, Cronan JE., Jr Bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis: targets for antibacterial drug discovery. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:305–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Cronan JE., Jr Escherichia coli thioesterase I, molecular cloning and sequencing of the structural gene and identification as a periplasmic enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9238–9245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie WW. Lipid Analysis. Bridgewater, UK: The Oily Press, PJ Barnes & Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DP, DeMendoza D, Polacco ML, Cronan JE., Jr β-hydroxydecanoyl thio ester dehydrase does not catalyze a rate-limiting step in Escherichia coli unsaturated fatty acid synthesis. Biochemistry. 1983;22:5897–5902. doi: 10.1021/bi00294a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan JE, Thomas J. Bacterial fatty acid synthesis and its relationships with polyketide synthetic pathways. Methods Enzymol. 2009;459:395–433. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04617-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan JE, Jr, Birge CH, Vagelos PR. Evidence for two genes specifically involved in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli . J. Bacteriol. 1969;100:601–604. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.2.601-604.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan JE, Jr, Weisberg LJ, Allen RG. Regulation of membrane lipid synthesis in Escherichia coli. Accumulation of free fatty acids of abnormal length during inhibition of phospholipid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:5835–5840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan JE, Jr, Li WB, Coleman R, Narasimhan M, de Mendoza D, Schwab JM. Derived amino acid sequence and identification of active site residues of Escherichia coli beta-hydroxydecanoyl thioester dehydrase. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:4641–4646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facklam R, Elliott JA. Identification, classification, and clinical relevance of catalase-negative, gram-positive cocci, excluding the streptococci and enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995;8:479–495. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Cronan JE. Escherichia coli unsaturated fatty acid synthesis: complex transcription of the fabA gene and in vivo identification of the essential reaction catalyzed by FabB. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:29526–29535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfine H, Panos C. Phospholipids of Clostridium butyricum. IV. Analysis of the positional isomers of monounsaturated and cyclopropane fatty acids and alk-1′-enyl ethers by capillary column chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 1971;12:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra DJ, Browse JA. Escherichia coli β-hydroxydecanoyl thioester dehydrase reacts with native C10 acyl-acyl-carrier proteins of plant and bacterial origin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;280:336–345. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RJ, Rock CO. Roles of the FabA and FabZ β-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratases in Escherichia coli fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:27795–27801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RJ, Rock CO. A triclosan-resistant bacterial enzyme. Nature. 2000;406:145–146. doi: 10.1038/35018162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isabella VM, Clark VL. Identification of a conserved protein involved in anaerobic unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in Neiserria gonorrhoeae : implications for facultative and obligate anaerobes that lack FabA. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;82:489–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa F, Haushalter RW, Burkart MD. Dehydratase-specific probes for fatty acid and polyketide synthases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:769–772. doi: 10.1021/ja2082334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Zirkle R, Metz JG, Braun L, Richter L, Van Lanen SG, Shen B. The role of tandem acyl carrier protein domains in polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6336–6337. doi: 10.1021/ja801911t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Morgan-Kiss RM, Campbell JW, Chan CH, Cronan JE. Expression of Vibrio harveyi acyl-ACP synthetase allows efficient entry of exogenous fatty acids into the Escherichia coli fatty acid and lipid A synthetic pathways. Biochemistry. 2010;49:718–726. doi: 10.1021/bi901890a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston NC, Goldfine H. Lipid composition in the classification of the butyric acid-producing clostridia. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1983;129:1075–1081. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-4-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass LR, Brock DJ, Bloch K. β-hydroxydecanoyl thioester dehydrase. I. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:4418–4431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber MS, Martin F, Lu Y, Houston S, Vedadi M, Dharamsi A, Fiebig KM, Schmid M, Rock CO. The structure of (3R)-hydroxyacylacyl carrier protein dehydratase (FabZ) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52593–52602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CY, Cronan JE. β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) is essential for bacterial fatty acid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51494–51503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leesong M, Henderson BS, Gillig JR, Schwab JM, Smith JL. Structure of a dehydratase-isomerase from the bacterial pathway for biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids: two catalytic activities in one active site. Structure. 1996;4:253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrakchi H, Choi KH, Rock CO. A new mechanism for anaerobic unsaturated fatty acid formation in Streptococcus pneumoniae . J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44809–44816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz JG, Roessler P, Facciotti D, Levering C, Dittrich F, Lassner M, Valentine R, Lardizabal K, Domergue F, Yamada A, et al. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by polyketide synthases in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Science. 2001;293:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1059593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan S, Kelly TM, Eveland SS, Raetz CR, Anderson MS. An Escherichia coli gene (FabZ) encoding (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl acyl carrier protein dehydrase. Relation to fabA and suppression of mutations in lipid A biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:32896–32903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Kiss RM, Cronan JE. The Lactococcus lactis FabF fatty acid synthetic enzyme can functionally replace both the FabB and FabF proteins of Escherichia coli and the FabH protein of Lactococcus lactis Arch. Microbiol. 2008;190:427–437. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris LJ, Wharry DM. Chromatographic behaviour of isomeric long-chain aliphatic compounds. I. Thin-layer chromatography of some oxygenated fatty acid derivatives. J. Chromatogr. A. 1965;20:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)97362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss CW, Wallance PL, Bosley GS. Identification of monounsaturated fatty acids of Aerococcus viridans with dimethyl disulfide derivatives and combined gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989;27:2130–2132. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.9.2130-2132.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynié L, Leckie SM, McMahon SA, Duthie FG, Koehnke A, Taylor JW, Alphey MS, Brenk R, Smith AD, Naismith JH. Structural insights into the mechanism and inhibition of the β-hydroxydecanoyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathavitharana KA, Arseculeratne SN, Aponso HA, Vijeratnam R, Jayasena L, Navaratnam C. Acute meningitis in early childhood caused by Aerococcus viridans . Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1983;286:1248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6373.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orikasa Y, Tanaka M, Sugihara S, Hori R, Nishida T, Ueno A, Morita N, Yano Y, Yamamoto K, Shibahara A, et al. pfaB products determine the molecular species produced in bacterial polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;295:170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-Beittenmiller D, Jaworski JG, Ohlrogge JB. In vivo pools of free and acylated acyl carrier proteins in spinach. Evidence for sites of regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1858–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi B, Fraser T, Mugford S, Dobson G, Sayanova O, Butler J, Napier JA, Stobart AK, Lazarus CM. Production of very long chain polyunsaturated omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:739–745. doi: 10.1038/nbt972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuerbrandt G, Goldfine H, Baronowsky PE, Bloch K. A novel mechanism for the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1961;236:PC70–PC71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Cronan JE. Functional replacement of the FabA and FabB proteins of Escherichia coli fatty acid synthesis by Enterococcus faecalis FabZ and FabF homologues. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:34489–34495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Zheng J, Zhang YM, Rock The structural biology of type II fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:791–831. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Sargent JR. High-resolution separation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by argentation thin-layer chromatography 1992, 623 403–407. J. Chromatogr. A. 1992;623:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YM, Rock CO. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:222–233. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JY, Yu QT, Liu BN, Huang ZH. Chemical modification in mass-spectrometry IV. 2-Alkenyl-4,4-dimethyloxazolines as derivatives for the double-bond location of long-chain olefinic acids. Biomed. Mass Spectrom. 1988;15:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Cheng J, Luo B, Feng S, Lin J, Wang S, Cronan JE, Wang H. Functions of the Clostridium acetobutylicium FabF and FabZ proteins in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.