Abstract

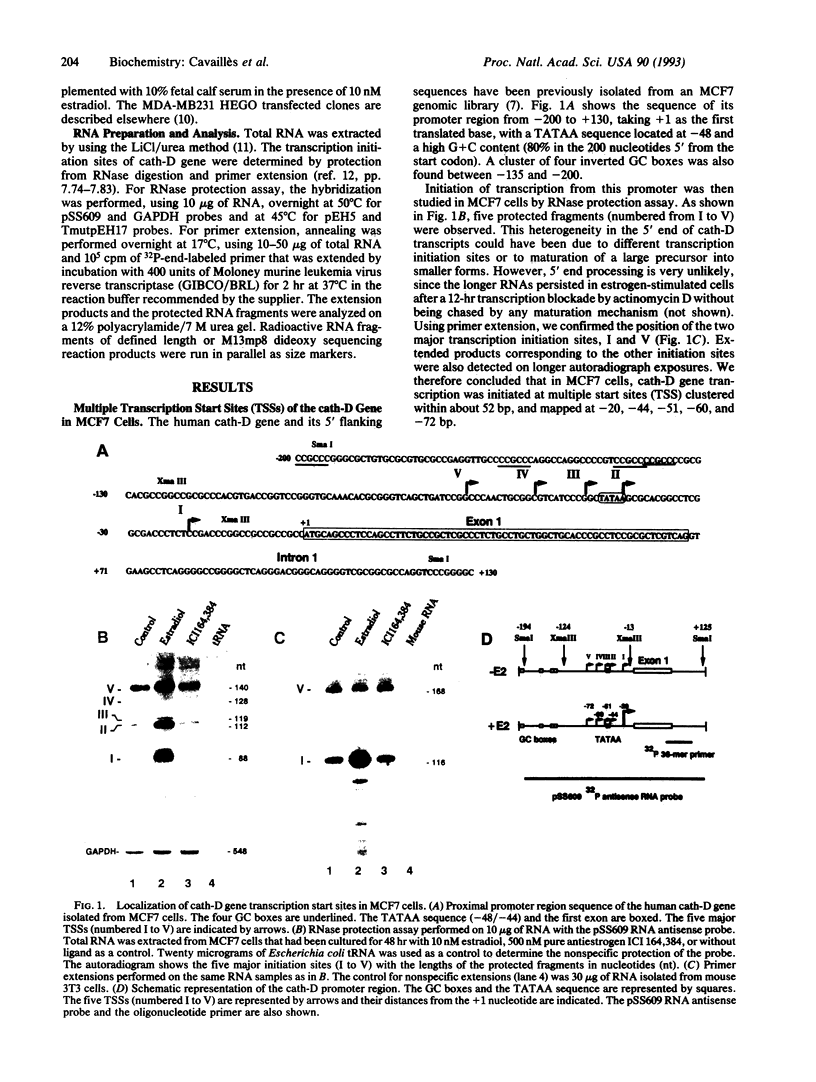

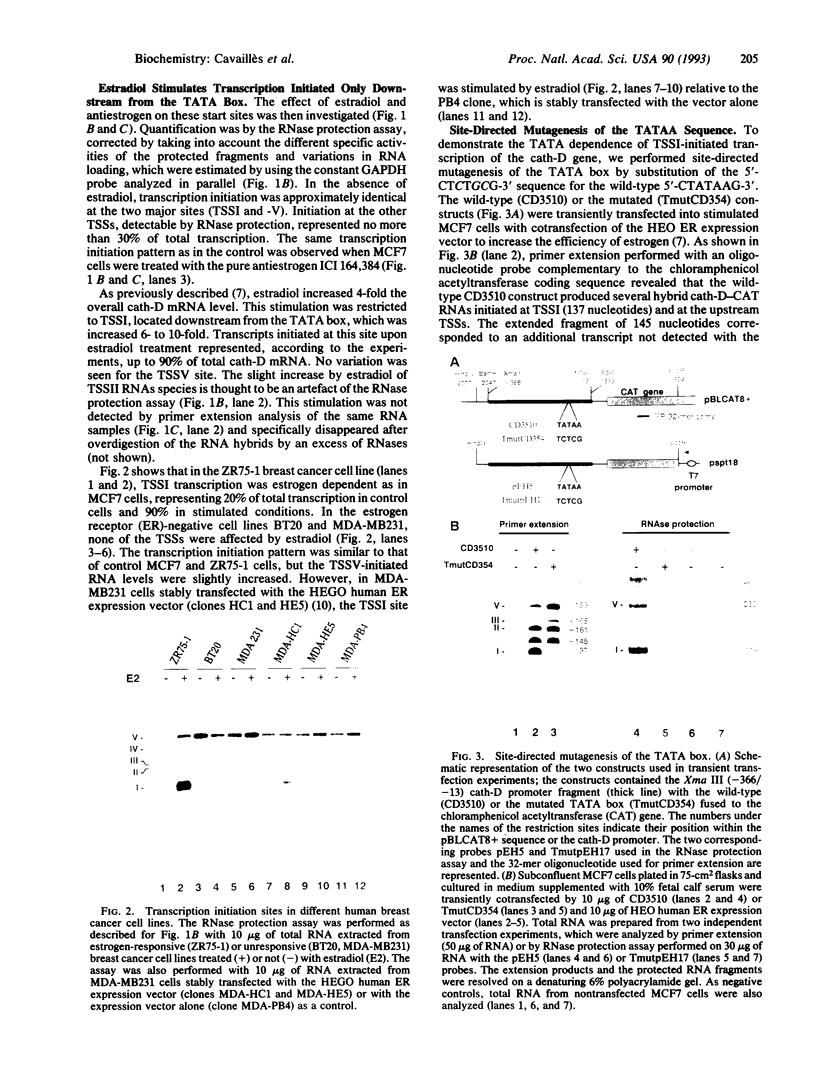

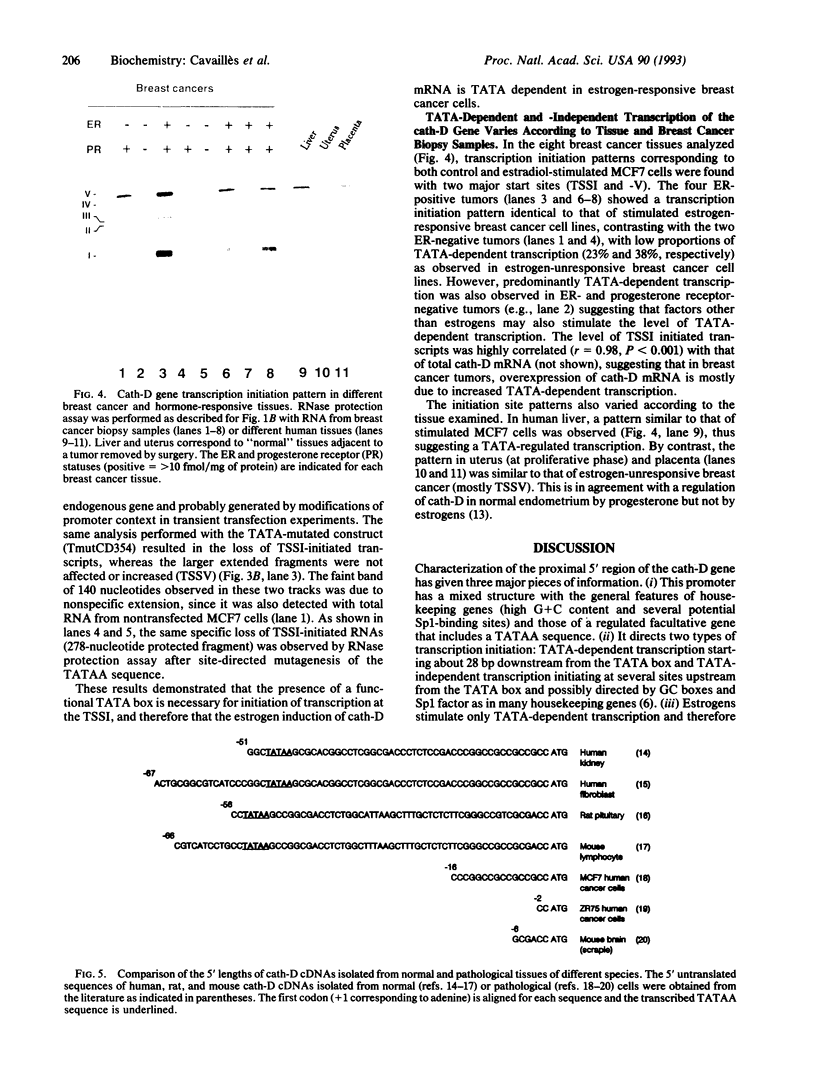

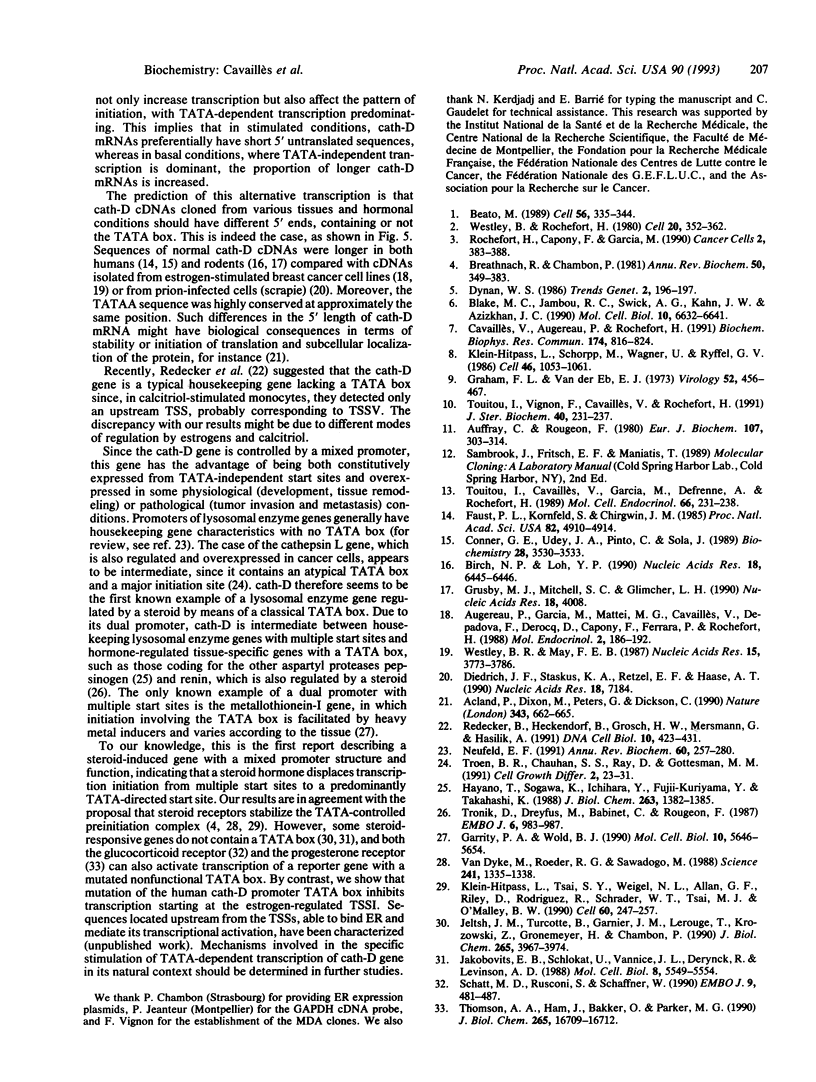

The cathepsin D (cath-D) gene, coding for a ubiquitous lysosomal aspartyl protease, is overexpressed in aggressive human breast cancers, and its transcription is induced by estrogens in hormone-responsive breast cancer cells. We have determined the structure and function of the proximal 5' upstream region of the human cath-D gene from MCF7 cells. We show that the promoter has a compound structure with features of both housekeeping genes (high G+C content and potential transcription factor Sp1 sites) and regulated genes (TATAA sequence). By RNase protection assay, we show that transcription is initiated at five major transcription sites (TSSI to -V) spanning 52 base pairs. In hormone-responsive breast cancer cells, estradiol increased by 6- to 10-fold the level of RNAs initiated at TSSI, which is located about 28 base pairs downstream from the TATA box. The specific regulation by estradiol of transcription starting at site I exclusively was confirmed by primer extension. Moreover, the same estradiol effect was observed in the ZR75-1 cell line and in MDA-MB231 estrogen-resistant breast cancer cells stably transfected with the estrogen receptor. Site-directed mutagenesis indicated that the TATA box is essential for initiation of cath-D gene transcription at TSSI. In breast cancer biopsy samples, high levels of TATA-dependent transcription were correlated with overexpression of cath-D mRNA. We conclude that cath-D behaves, depending on the conditions, as a housekeeping gene with multiple start sites or as a hormone-regulated gene that can be controlled from its TATA box.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Acland P., Dixon M., Peters G., Dickson C. Subcellular fate of the int-2 oncoprotein is determined by choice of initiation codon. Nature. 1990 Feb 15;343(6259):662–665. doi: 10.1038/343662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffray C., Rougeon F. Purification of mouse immunoglobulin heavy-chain messenger RNAs from total myeloma tumor RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1980 Jun;107(2):303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb06030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augereau P., Garcia M., Mattei M. G., Cavailles V., Depadova F., Derocq D., Capony F., Ferrara P., Rochefort H. Cloning and sequencing of the 52K cathepsin D complementary deoxyribonucleic acid of MCF7 breast cancer cells and mapping on chromosome 11. Mol Endocrinol. 1988 Feb;2(2):186–192. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-2-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato M. Gene regulation by steroid hormones. Cell. 1989 Feb 10;56(3):335–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch N. P., Loh Y. P. Cloning, sequence and expression of rat cathepsin D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Nov 11;18(21):6445–6446. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake M. C., Jambou R. C., Swick A. G., Kahn J. W., Azizkhan J. C. Transcriptional initiation is controlled by upstream GC-box interactions in a TATAA-less promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Dec;10(12):6632–6641. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breathnach R., Chambon P. Organization and expression of eucaryotic split genes coding for proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:349–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavailles V., Augereau P., Rochefort H. Cathepsin D gene of human MCF7 cells contains estrogen-responsive sequences in its 5' proximal flanking region. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991 Jan 31;174(2):816–824. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91491-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner G. E., Udey J. A., Pinto C., Sola J. Nonhuman cells correctly sort and process the human lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D. Biochemistry. 1989 Apr 18;28(8):3530–3533. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich J. F., Staskus K. A., Retzel E. F., Haase A. T. Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA encoding mouse cathepsin D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Dec 11;18(23):7184–7184. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust P. L., Kornfeld S., Chirgwin J. M. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for human cathepsin D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Aug;82(15):4910–4914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity P. A., Wold B. J. Tissue-specific expression from a compound TATA-dependent and TATA-independent promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Nov;10(11):5646–5654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham F. L., van der Eb A. J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973 Apr;52(2):456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusby M. J., Mitchell S. C., Glimcher L. H. Molecular cloning of mouse cathepsin D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Jul 11;18(13):4008–4008. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano T., Sogawa K., Ichihara Y., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Takahashi K. Primary structure of human pepsinogen C gene. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jan 25;263(3):1382–1385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobovits E. B., Schlokat U., Vannice J. L., Derynck R., Levinson A. D. The human transforming growth factor alpha promoter directs transcription initiation from a single site in the absence of a TATA sequence. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Dec;8(12):5549–5554. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch J. M., Turcotte B., Garnier J. M., Lerouge T., Krozowski Z., Gronemeyer H., Chambon P. Characterization of multiple mRNAs originating from the chicken progesterone receptor gene. Evidence for a specific transcript encoding form A. J Biol Chem. 1990 Mar 5;265(7):3967–3974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Hitpass L., Schorpp M., Wagner U., Ryffel G. U. An estrogen-responsive element derived from the 5' flanking region of the Xenopus vitellogenin A2 gene functions in transfected human cells. Cell. 1986 Sep 26;46(7):1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Hitpass L., Tsai S. Y., Weigel N. L., Allan G. F., Riley D., Rodriguez R., Schrader W. T., Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. The progesterone receptor stimulates cell-free transcription by enhancing the formation of a stable preinitiation complex. Cell. 1990 Jan 26;60(2):247–257. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld E. F. Lysosomal storage diseases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:257–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.001353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redecker B., Heckendorf B., Grosch H. W., Mersmann G., Hasilik A. Molecular organization of the human cathepsin D gene. DNA Cell Biol. 1991 Jul-Aug;10(6):423–431. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort H., Capony F., Garcia M. Cathepsin D in breast cancer: from molecular and cellular biology to clinical applications. Cancer Cells. 1990 Dec;2(12):383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatt M. D., Rusconi S., Schaffner W. A single DNA-binding transcription factor is sufficient for activation from a distant enhancer and/or from a promoter position. EMBO J. 1990 Feb;9(2):481–487. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A. A., Ham J., Bakker O., Parker M. G. The progesterone receptor can regulate transcription in the absence of a functional TATA box element. J Biol Chem. 1990 Oct 5;265(28):16709–16712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touitou I., Cavaillès V., Garcia M., Defrenne A., Rochefort H. Differential regulation of cathepsin D by sex steroids in mammary cancer and uterine cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1989 Oct;66(2):231–238. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(89)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touitou I., Vignon F., Cavailles V., Rochefort H. Hormonal regulation of cathepsin D following transfection of the estrogen or progesterone receptor into three sex steroid hormone resistant cancer cell lines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;40(1-3):231–237. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90187-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troen B. R., Chauhan S. S., Ray D., Gottesman M. M. Downstream sequences mediate induction of the mouse cathepsin L promoter by phorbol esters. Cell Growth Differ. 1991 Jan;2(1):23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronik D., Dreyfus M., Babinet C., Rougeon F. Regulated expression of the Ren-2 gene in transgenic mice derived from parental strains carrying only the Ren-1 gene. EMBO J. 1987 Apr;6(4):983–987. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke M. W., Roeder R. G., Sawadogo M. Physical analysis of transcription preinitiation complex assembly on a class II gene promoter. Science. 1988 Sep 9;241(4871):1335–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.3413495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westley B. R., May F. E. Oestrogen regulates cathepsin D mRNA levels in oestrogen responsive human breast cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 May 11;15(9):3773–3786. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.9.3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westley B., Rochefort H. A secreted glycoprotein induced by estrogen in human breast cancer cell lines. Cell. 1980 Jun;20(2):353–362. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]