Abstract

Background

The high prevalence of asthma among urban African American (AA) populations has attracted research attention while the prevalence among rural AA populations is poorly documented.

Objective

To compare the prevalence of asthma among AA youth in rural Georgia and urban Detroit, Michigan.

Methods

The prevalence of asthma was compared in population-based samples of 7297 youth attending Detroit public high schools and in 2523 youth attending public high schools in rural Georgia. Current asthma was defined as a physician diagnosis and symptoms in the previous 12 months. Undiagnosed asthma was defined as multiple respiratory symptoms in the previous 12 months without a physician diagnosis.

Results

In Detroit, 6994 (95.8%) youth were AA compared to 1514 (60.0%) in GA. Average population density in high school ZIP codes was 5628 people/mi2 in Detroit and 45.1 people/mi2 in GA. The percent of poverty and of students qualifying for free or reduced lunches were similar in both areas. The prevalence of current diagnosed asthma among AA youth in Detroit and GA were similar: 15.0% (95% CI 14.1–15.8), and 13.7% (CI 12.0–17.1) (p=.22), respectively. Undiagnosed asthma prevalence in AA youth was 8.0% in Detroit and 7.5% in GA (p=.56). Asthma symptoms were reported more frequently among those with diagnosed asthma in Detroit while those with undiagnosed asthma in Georgia reported more symptoms.

Conclusions

Among AA youth living in similar socioeconomic circumstances, asthma prevalence is as high in rural Georgia as it is in urban Detroit suggesting that urban residence is not an asthma risk factor.

Clinical Implications

Asthma prevalence was as common among African American high school students in rural Georgia as among students in urban Detroit, Michigan. Asthma is more likely related to poverty than urban residence.

Keywords: urban, rural, African American, asthma, prevalence, inner city, high school students, youth

Introduction

In the United States many studies have focused on the increased prevalence and greater morbidity of asthma among both adults and children in impoverished urban areas, often colloquially referred to as “inner cities”.1–7 However, few studies have compared the prevalence of asthma between impoverished urban populations and populations of similar racial and socioeconomic status living outside urban areas.1;8 Comparisons of urban and non-urban populations for asthma prevalence are complicated by numerous factors including the marked residential segregation of African Americans (AA) in urban areas.9–11 The understanding that asthma is unusually frequent and severe in urban populations has led to major funding initiatives to study asthma among urban residents. For example, funding initiatives of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) have ranged from $18.7 to ~$70 million for urban asthma.5 The areas studied in these initiatives are not only urban but also areas in which relatively large proportions of the population live in impoverished circumstances. These intensely funded efforts have described many features related to urban asthma under the assumption that these features are unique to urban environments.1;2;4;12;13 It is also assumed that the same factors lead to both a higher prevalence and greater morbidity of asthma. However few investigators have directed their attention to asthma in rural AA populations of similar socioeconomic status.1;3;5;14;15 This is in spite of the fact that 19.3% of the population lives in rural areas of the United States according to the 2010 census.

It is important to assess whether AA children living in urban environments are at higher risk of asthma than those living in rural areas because clear differences would suggest that specific environmental dissimilarities, such as the built environment or urban pollution, were causally related to the prevalence of asthma. By way of contrast, if the prevalence of asthma was the same in populations living in similar socioeconomic circumstances, whether urban or rural, it would suggest that socioeconomic factors or ancestral heritage constitute a major risk for asthma and not living in an urban environment.

Statistics from government agencies are highly valuable for looking at asthma across the US but these statistics rarely attempt to compare urban and rural populations within socioeconomic strata.16;17 Statistics based on samples broadly representative of the entire United States do show dramatic disparities in asthma by self-identified racial or ethnic groups.17 While a number of studies have shown that the prevalence of asthma is similar in rural children and urban children, none of these studies have compared populations living in the large Northeastern or Midwestern cities where high rates of asthma were originally reported.8;18–20 To properly compare populations from widely varying areas it is important that the same screening instrument be used in both locations and that study methodologies are similar.

The purpose of this study was to compare the prevalence and morbidity of asthma among high school students attending public high schools in Detroit, Michigan with students of similar age and race attending public high schools in four rural counties of Georgia using identical methods.

Methods

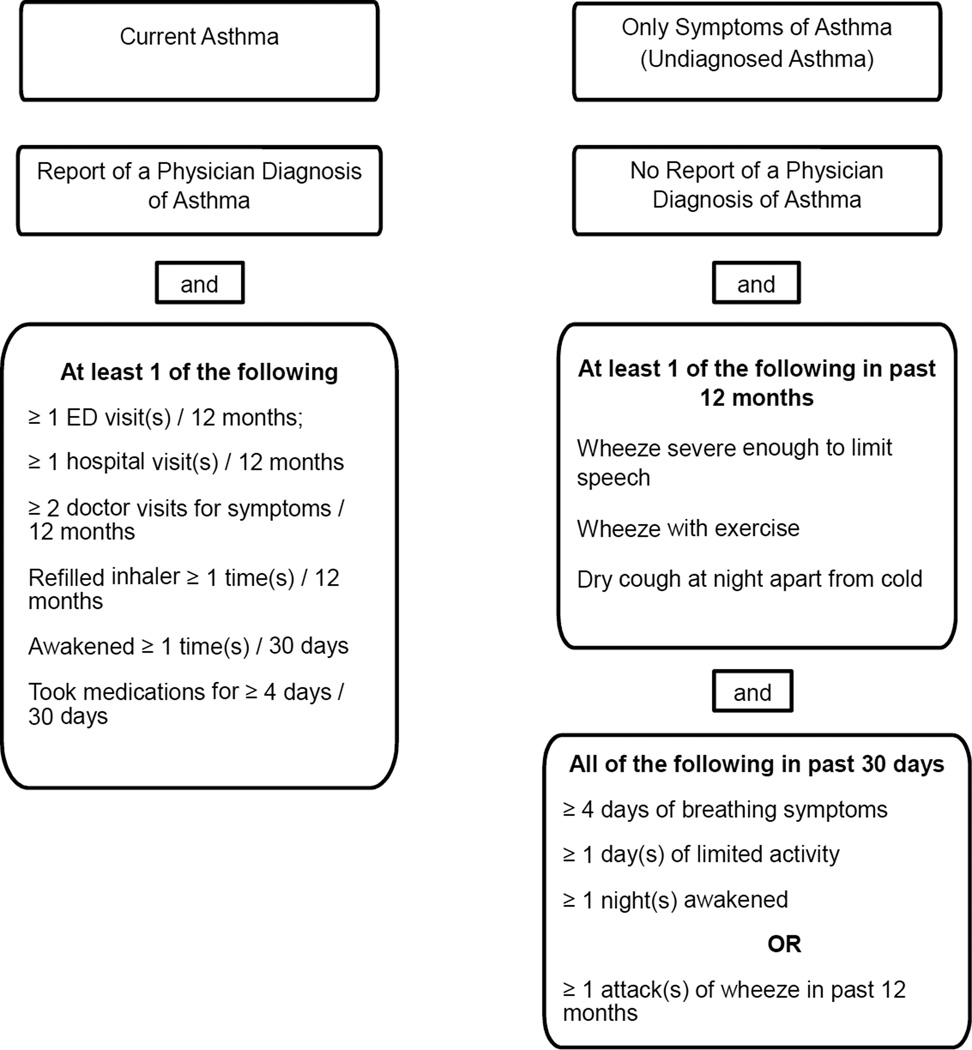

Reports of asthma and asthma symptoms were collected using a Lung Health Survey (LHS) administered to students attending six public high schools in urban Detroit, Michigan and those attending four public high schools in rural counties of Georgia. The LHS has been used in previous studies.21;22 This survey contains questions from well recognized instruments including the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children (ISAAC) and is based on recommendations and classifications used in the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (Expert Panel Report III).23;24 Specifically, youth reporting any physician diagnosis of asthma were considered to have life-time asthma. Current asthma was defined as a physician diagnosis and use of either medications or acute respiratory symptoms in the previous 12 months. Undiagnosed asthma was defined as multiple respiratory symptoms in the previous 12 months but no reported physician diagnosis of asthma. The schema of variables used to classify youth as having current diagnosed asthma, undiagnosed asthma, or no current asthma is the same as used in our previous studies as shown in Figure 1.25

Figure 1.

Schematic of criteria for classifying subjects as having current diagnosed or current undiagnosed asthma.

The methods and results of using the LHS in the Detroit high schools have been previously reported.25 Students were recruited from the fall of 2007 through the fall of 2008. All of the studies in the Detroit public high schools were approved by the institutional review board of Henry Ford Health System and the Detroit Public Schools Office of Research, Evaluation, and Assessment. All of the high schools approached agreed to participate in the study. Studies in the Detroit Public Schools attempted to reach all students through their English class since school policy requires all students to be enrolled in an English class during each year of high school.

In Georgia, participating schools were located in Burke, Jefferson, Wilkes and McDuffie counties. Each of these counties has a single public high school and all four of these counties fit the most commonly used US Department of Agriculture definition of “rural’, no county has a population center of greater than 50,000 inhabitants (the total population of the largest county was 23,316 in the 2010 US census). Each school was approached through the county school superintendent and high school principal and all schools approached agreed to participate. The counties selected were also selected for their proximity to the medical school in Augusta, GA. All of the studies in Georgia were approved by the Human Assurance Committee of Georgia Regents University and by the respective school superintendents in each county. The parents of all students in the four Georgia high schools were given the option of not allowing their student to participate in the LHS (passive opt-out). The students were told that if they did not wish to participate they did not need to complete the LHS. Completion of the survey was considered as student assent for participation. These were the same parental consent/student assent processes approved and used in the Detroit survey. The LHS was completed by students during their home room period from August, 2009 through December, 2010. School policies stated that all students in these four schools were to be assigned a home room.

In both Detroit and Georgia students were asked to indicate their race as: Latino/Hispanic, Black/African American, Asian, Native American/American Indian, White/Non-Latino, and other.

To provide a better understanding of key differences between the Detroit and Georgia schools, public data sources were used to find the number of students in each school during the year of the survey, the percentage of students reported as Black (AA), the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch, the population density defined as the number of persons per square mile, and the number of physicians practicing in the ZIP codes where the schools are located. Physicians were divided into those typically providing primary care, who could be expected to provide care for adolescents with asthma (family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, preventive medicine, obstetrics and gynecology), those providing specialty care for asthma (allergy, pulmonology) and all other specialties. When a practice was listed but no indication of the number of physicians was given for the practice it was counted as one physician.

One parent or guardian of each participating high school student was invited to participate in two telephone interviews concerning their student’s health. Among the interview questions were questions related to socioeconomic status including: whether they owned or rented their home, the highest level of education they had completed, the total annual income of the home and the amount they paid each month for their home, either as rent or mortgage. The responses to these questions were compared to assess differences in socioeconomic status of the students.

Statistical methods

Characteristics between groups, including the prevalence of lifetime and current asthma, were compared using Pearson chi-square tests with exact (Clopper-Pearson) confidence intervals (CIs). Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare groups on number of visits or symptom days. Self-reported racial categories were collapsed into AA, White (non-Hispanic), other (including Hispanic) and those who failed to report a category. For socioeconomic information the frequencies and percentages across groups were compared with Fisher’s Exact test due to low expected frequencies in some cells. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum was used to compare median housing payments by racial groups.

Results

The selection and rate of participation of the high school students in Detroit has been previously published as detailed in the methods.25 In total, 18,398 students were reported as enrolled in grades 9–12 in the participating high schools, and 11,551 were reported as enrolled in English classes with an estimated attendance of 9,125 on the days of survey administration. The LHS was completed and returned by 7,878 (86.3%) of the students enrolled in the English classes. A total of 7297 had sufficient information to determine current asthma prevalence and symptoms.

In Georgia, school records indicated a total population of 2,952 students in the four high schools and 145 (4.9%) were not permitted to participate by their parents yielding 2807 to be surveyed. Surveys were completed by 2,636 (93.9%) students during the single day the LHS was given in each school. The reasons some students failed to complete a survey vary and including tardiness, absenteeism, participating in some activity other than home room, and 112 either marked “don’t know” or did not answer the question on a doctor’s diagnosis of asthma leaving 2,523 for analysis.

Selected characteristics of the ZIP codes in which the high schools of participating students were located are displayed in Table I. The Detroit high schools on average had larger enrollments and had higher percentages of AA students. The average percentage of students eligible for free or reduced cost lunches (74.2% in Detroit versus 73.3% in Georgia) and the average percentage of poverty in the ZIP codes based on federal standards (23.0% in Detroit versus 22.8% in Georgia) were similar. The major difference is the population densities of the school ZIP codes with an average of 5,627.8 persons/mi2 in Detroit and only 45.1 persons/mi2 in Georgia. There were nearly twice as many physicians; both primary care and total, in the Detroit ZIP codes compared to Georgia and only the Detroit ZIP codes had any asthma specialists. However, the number of primary care physicians per 10,000 persons was similar in both Detroit and Georgia ZIP codes. The range in Detroit ZIP codes was 1.8–8.8 primary care physicians per 10,000 population, in Georgia 1.8–8.5 primary care physician per 10,000 population and in the entire United States there were approximately 8.0 primary care physicians per 10,000 population in 2010.26

Table I.

Selected characteristics of ZIP codes in which high schools of Participating Students were located in rural Georgia counties and Detroit, Michigan

| Participating High Schools |

Enrollment during recruitment period |

% Black Students in school* |

% Eligible Free or Reduced Lunch in school** |

% Poverty in School Zip Code*** |

Population Density*** people/sq mi |

Physician Practices, primary care / non-primary care specialties / asthma specialists = total physicians** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Detroit, Michigan High Schools (2007 school year)* | ||||||

| 1 | 2134 | 99.0 | 72.6 | 22.9 | 6,054.7 | 14/3/0 = 17 |

| 2 | 1598 | 99.0 | 78.0 | 16.0 | 7,749.1 | 19/9/1 = 29 |

| 3 | 1275 | 98.0 | 69.8 | 17.5 | 5,581.2 | 22/11/0 = 33 |

| 3 | 1944 | 99.0 | 68.1 | 11.5 | 7,102.7 | 7/3/1 = 11 |

| 5 | 1559 | 99.0 | 79.6 | 38.1 | 3,236.1 | 4/1/0 = 5 |

| 6 | 2519 | 99.0 | 76.8 | 32.3 | 4,043.0 | 20/20/1 = 41 |

| Average | 1838.2 | 98.9 | 74.2 | 23.0 | 5627.8 | 14.3/7.8/0.5 = 22.7 |

| Rural Georgia High Schools (2010 school year)* | ||||||

| 1 | 1,290 | 66.8 | 78.3 | 29.7 | 38.5 | 12/9/0 = 21 |

| 2 | 864 | 71.5 | 81.2 | 25.0 | 28.7 | 3/1/0 = 4 |

| 3 | 1,102 | 51.8 | 62.5 | 19.1 | 83.3 | 14/1/0 = 15 |

| 4 | 468 | 48.1 | 70.5 | 17.4 | 29.9 | 9/3/0 =12 |

| Average | 931 | 67.4 | 73.3 | 22.8 | 45.1 | 9.5/3.5/0 = 13 |

2007 enrollment from www.city-data.com/ accessed on 4/16/2014

School statistics from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/ accessed on 5/13/2013

% Poverty, Population density as persons per square mile, and physicians practicing in ZIP code of high school.

Poverty and population density statistics from http://www.usa.com/ accessed on 5/14/2013.

The prevalence of current physician diagnosed asthma in relationship to selected demographic characteristics is shown in Table II. The prevalence of current asthma in AA compared to other racial groups in Detroit is 15.0 (95% CI 14.1–15.8) vs 11.4 (5.3–20.5), p=.37, respectively, while for Georgia it is 13.7% (12.0–15.6) versus 10.4% (8.5–12.4), p=.012. Undiagnosed asthma did not differ between sites, races or other characteristics as shown in supplemental Table I.

Table II.

Prevalence of current physician diagnosed asthma by site and demographic characteristics

| n/N | % | 95% Cis** | p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | ||||

| Detroit | 1095/7297 | 15.0 | 14.2 – 15.9 | |

| Georgia | 311/2523 | 12.3 | 11.1 – 13.7 | 0.001 |

| Male* | ||||

| Detroit | 480/3265 | 14.7 | 13.5 – 16.0 | |

| Georgia | 156/1240 | 12.6 | 10.8 – 14.6 | 0.07 |

| Female* | ||||

| Detroit | 579/3812 | 15.2 | 14.1 – 16.4 | |

| Georgia | 155/1267 | 12.2 | 10.5 – 14.2 | 0.010 |

| African Am. | ||||

| Detroit | 1047/6994 | 15.0 | 14.1 – 15.8 | |

| Georgia | 208/1514 | 13.7 | 12.0 – 15.6 | 0.22 |

| White | ||||

| Detroit | 3/32 | 9.4 | 2.0 – 25.0 | |

| Georgia | 92/880 | 10.4 | 8.5– 12.7 | 0.84 |

| Other | ||||

| Detroit | 6/47 | 12.8 | 4.8 – 25.7 | |

| Georgia | 10/105 | 9.5 | 4.7 – 16.8 | 0.57 |

| Unk/missing | ||||

| Detroit | 39/224 | 17.4 | 12.7 – 23.0 | |

| Georgia | 1/24 | 4.2 | 0.1 – 21.1 | 0.14 |

The sum of male and female participants is less than the total number of participants because 16 students in GA and 220 in Detroit did not provide gender.

P-values are from Pearson chi-square tests with exact (Clopper-Pearson) conficence intervals.

Because of the very small numbers of non-AA among the Detroit participants the main comparisons of interest are between AA students in Detroit and Georgia. When only AA youth are considered, the prevalence of lifetime asthma, current diagnosed asthma and current undiagnosed asthma did not significantly differ by either location or by gender as shown in Table III, although the prevalence of undiagnosed asthma in males was significantly higher in Detroit compared to Georgia (5.5% versus 3.6%, respectively, p=0.040).

Table III.

Comparison of diagnosed and current undiagnosed asthma prevalence by site for African American youth

| Lifetime Diagnosed Asthma |

n/N | % |

95% Cis* |

p- value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | |||||

| Detroit | 1324/6994 | 18.9 | 18.0 – 19.9 | ||

| Georgia | 293/1514 | 19.4 | 17.4 – 21.4 | 0.70 | |

| Male | |||||

| Detroit | 652/3231 | 20.2 | 18.8 – 21.6 | ||

| Georgia | 158/743 | 21.3 | 18.4 – 24.4 | 0.51 | |

| Female | |||||

| Detroit | 672/3763 | 17.9 | 16.6 – 19.1 | ||

| Georgia | 135/770 | 17.5 | 14.9 – 20.4 | 0.83 | |

| Current Diagnosed Asthma | |||||

| All | |||||

| Detroit | 1047/6994 | 15.0 | 14.1 – 15.8 | ||

| Georgia | 208/1514 | 13.7 | 12.0 – 15.6 | 0.22 | |

| Male | |||||

| Detroit | 476/3231 | 14.7 | 13.5 – 16.0 | ||

| Georgia | 107/743 | 14.4 | 12.0 – 17.1 | 0.82 | |

| Female | |||||

| Detroit | 571/3763 | 15.2 | 14.0 – 16.4 | ||

| Georgia | 101/770 | 13.1 | 10.8 – 15.7 | 0.14 | |

| Current Undiagnosed Asthma | |||||

| All | |||||

| Detroit | 558/6994 | 8.0 | 7.4 – 8.6 | ||

| Georgia | 114/1514 | 7.5 | 6.2 – 9.0 | 0.56 | |

| Male | |||||

| Detroit | 177/3231 | 5.5 | 4.7 – 6.3 | ||

| Georgia | 27/743 | 3.6 | 2.4 – 5.2 | 0.040 | |

| Female | |||||

| Detroit | 381/3763 | 10.1 | 9.2 – 11.1 | ||

| Georgia | 86/770 | 11.2 | 9.0 – 13.6 | 0.3927 | |

P-values are from Pearson chi-square tests with exact (Clopper-Pearson) conficence intervals.

When the frequency of asthma symptoms and morbidity measures were compared by sites among AA students with current asthma, students in Detroit reported significantly more symptoms in the past 30 days for all questions of symptoms as shown in Table IV. The students in Detroit also reported more hospitalizations, however, there were no differences in reported symptoms or need for other forms of health care in the previous 12 months by location. Considering students with undiagnosed asthma, those in Georgia reported significantly more episodes of wheezing with exercise, nights with coughing, ER visits, doctor visits, and days requiring medications, and school days missed for any reason compared to those undiagnosed in Detroit, supplemental Table II.

TABLE IV.

Comparison of self-reported symptoms by site among African American students with current diagnosed asthma

| Detroit N=1047* |

Georgia N=208* |

p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 12 months: | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Wheeze with exercise | 0.56 | ||

| Yes | 690 (66.5%) | 121 (64.4%) | |

| No | 347 (33.5%) | 67 (35.6%) | |

| Severe Wheeze | 0.065 | ||

| Yes | 360 (34.6%) | 54 (27.8%) | |

| No | 679 (65.4%) | 140 (72.2%) | |

| Cough at night | 0.99 | ||

| Yes | 577 (55.6%) | 110 (55.6%) | |

| No | 461 (44.4%) | 88 (44.4%) | |

| In the past 12 months: | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | |

| ED visits | 1.36 (2.06) | 1.14 (1.78) | 0.22 |

| Median (IQR†) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | |

| Doctor visits | 1.79 (2.11) | 1.74 (1.86) | 0.70 |

| Median (IQR†) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Hospitalizations | 0.51 (1.43) | 0.43 (1.39) | 0.032 |

| Median (IQR†) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Refill your prescription | 2.55 (2.78) | 2.35 (2.30) | 0.28 |

| Median (IQR†) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (,5–4) | |

| In the past 30 days: | |||

| Asthma symptom days | 2.93 (3.14) | 1.98 (2.46) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR†) | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Slow down or stop normal activity | 2.92 (3.24) | 1.87 (2.71) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR†) | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Nights awakened by trouble breathing | 2.27 (2.83) | 1.55 (2.35) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR†) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | |

| Changed plans because of trouble breathing | 0.90 (1.97) | 0.64 (1.59) | 0.041 |

| Median (IQR†) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Took medications for breathing | 2.93 (3.42) | 2.27 (3.02) | 0.015 |

| Median (IQR†) | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Missed school for any reason | 2.33 (2.65) | 1.62 (2.14) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR†) | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Missed school because of breathing symptoms | 0.99 (1.93) | 0.71 (1.55) | 0.029 |

| Median (IQR†) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

Numbers vary because some students did not answer all questions or indicated that they did not know the answer to some questions.

Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare number of time data between the two sites. Pearson chi-square tests were used to compare binary data.

IQR = interquartile range

In Georgia, 283, and in Detroit, 355, parents or guardians participated in a questionnaire at the beginning of the study. In Georgia, whites had significantly higher average levels of education, family income and paid significantly more per month for housing compared to AA as shown in supplemental Table III. (There were insufficient numbers of whites in Detroit for meaningful comparison.)

Discussion

We initially found a higher prevalence of asthma in Detroit compared to rural Georgia but this appears to be the result of the larger number of whites participating in Georgia and the significantly lower prevalence of asthma in the white students. When the comparison was restricted to AA high school youth, we found no significant difference in the prevalence of every having diagnosed asthma, current physician-diagnosed asthma and of undiagnosed asthma in urban Detroit and rural Georgia. These findings are important for several reasons. Most importantly, the findings suggest that a high risk of asthma is not unique to urban residents but more likely a risk associated with impoverished living conditions, specifically financial and social hardships.18;27;28 These findings also suggests that research designed to identify allergens or other exposures unique to urban environments will only minimally contribute to solving the large disparities in asthma seen by race and ethnicity in the United States. Our findings are also consistent with a hypothesis of a racial difference in asthma risk, but other studies point toward poor housing, both urban and rural, as a more dominant risk factor for asthma than racial differences.28–30 However, racial differences in the risk of asthma should be carefully examined in populations of similar socioeconomic status adjusting for premature birth.31;32

Consistent with an increased risk related to poor housing or other factors associated with living in impoverished conditions was our finding that the levels of indicators of poverty were quite similar for the students in Detroit and Georgia. The percentages of students qualifying for free or reduced cost school lunches and the percentages of poverty in the ZIP codes where the high schools were located were similar.

In Georgia, where there were adequate numbers of participating parents for statistical comparison, white parents reported significantly higher levels of three indicators of socioeconomic status than did AA parents. The higher indicators of socioeconomic status are consistent with a hypothesis that impoverished living conditions are a major factor in asthma prevalence, but these findings do not address possible racial differences in asthma risk. A direct statistical comparison of the parent reported incomes and housing costs was not done because of the difficulties in adjusting for the relative costs of living and housing between the two locations. The more global measures of percentage of families living below the Federal poverty level and students qualifying for meal subsidies appeared more appropriate.

The numbers of primary care physicians per 10,000 population were also somewhat lower in the areas studied compared to the national average for the United States. Unfortunately, this study did not attempt to assess either the access to or the quality of primary care for these students.

Consistent with many other studies of inner city asthma we found a high prevalence of asthma among teenage high school students living in urban Detroit, Michigan.4;7 However, when we restricted our analyses to AA students the prevalence of lifetime asthma, current diagnosed asthma and undiagnosed asthma were not statistically significantly different between urban Detroit and rural Georgia. The lack of significance was not due to limited statistical power since a total of 10,073 high school students were surveyed: 7,297 in Detroit and 2,523 in Georgia. It is more likely we found similar prevalences of asthma in both locations because we compared students of the same racial group living under similar socioeconomic circumstances.

Similar to other studies we found a substantial number of students who did not report a diagnosis of asthma from a physician or other health care provider who nonetheless reported multiple asthma-like symptoms in the previous year.7;33–35 These undiagnosed students do report ED and physician visits and hospitalizations along with the use of medications for asthma suggesting that some may deny an asthma diagnosis or they may have been given an alternative diagnosis or failed to be diagnosed by their health care provider. However, if these students were given a diagnosis of asthma it is possible that their asthma management could be improved.

It is logical to compare these two populations since both populations were surveyed for asthma using the same LHS instrument utilizing essentially the same method of having students complete the LHS during school sessions which maximized the likelihood of surveying all students in all of the participating public high schools. A limitation is the fact that the two populations were surveyed approximately three years apart (2007–2008 in Detroit and 2009–2010 in Georgia). However there are few indications of substantial increase or decreases in asthma during this interval in Michigan or Georgia.36 Another study strength was the ability to survey relatively large, geographically representative, populations of similar ages. In all schools a passive opt-out consent procedure was allowed and rates of LHS completion were high in all schools. The same algorithm was used to classify students as having current diagnosed asthma and undiagnosed asthma in both studies. Additionally our surveys required at least a positive response to having a diagnosis of asthma and recent asthma symptoms to be considered as having current diagnosed asthma and at least two symptoms of wheezing or wheezing plus three other symptoms in the past 30 days to be considered as having undiagnosed asthma.

There were weaknesses in this study. As in all large surveys it was not feasible to externally validate the responses students gave to the LHS questionnaires. It is possible that some students exaggerated or imagined symptoms but we have no reason to suspect that this varied by location. Also, our survey findings are similar to those of others using similar methods in urban populations.7 Inevitably some students were missed and not screened for a variety of reasons in both locations. It is possible that those with asthma would be more likely to be absent on the day of the survey and this may have been more likely in Detroit, since Detroit students with asthma reported more missed school days. However, the rate of participation was high in both locations indicating that relatively few students were missed thus reducing the probability of substantially influencing the prevalence of asthma. We did not collect information concerning whether any of the students in rural Georgia lived on farms but other information suggests that few of these public high school students lived on farms. Our sampling was geographically based on high school districts even though not all teenage individuals attend public high schools in either Detroit or Georgia. We did not include students attending private schools who may be different with respect to asthma prevalence compared to students in public schools.

In summary, we did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of life-time, current diagnosed or undiagnosed asthma among AA high school youth residing in urban Detroit compared to AA youth residing in rural Georgia even though there are many environmental and climatic differences between these two locations. This finding strongly suggests that major characteristics associated with the prevalence of asthma in these urban and rural youth are the similarity in socioeconomic circumstances and reported ancestry, but not differences in local population density. This conclusion and the question of ancestral risks should be carefully examined in future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the schools who allowed students to participate and who facilitated the studies in both Georgia and in Detroit, MI.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards R01HL092412, R01HL06897 and the Fund for Henry Ford Hospital.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- AA

African American

- LHS

Lung Health Survey

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Busse WW. The National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases networks on asthma in inner-city children: an approach to improved care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breysse PN, Diette GB, Matsui EC, Butz AM, Hansel NN, McCormack MC. Indoor air pollution and asthma in children. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:102–106. doi: 10.1513/pats.200908-083RM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd RS, Joad JP. Urban asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:68–74. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000199001.68908.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss KB, Gergen PJ, Crain EF. Inner-city asthma. The epidemiology of an emerging US public health concern. Chest. 1992;101:362S–367S. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.362s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Togias A, Fenton MJ, Gergen PJ, Rotrosen D, Fauci AS. Asthma in the inner city: the perspective of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheehan WJ, Rangsithienchai PA, Wood RA, et al. Pest and allergen exposure and abatement in inner-city asthma: a work group report of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Indoor Allergy/Air Pollution Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant-Stephens T, West C, Dirl C, Banks T, Briggs V, Rosenthal M. Asthma prevalence in Philadelphia: description of two community-based methodologies to assess asthma prevalence in an inner-city population. J Asthma. 2012;49:581–585. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.690476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valet RS, Perry TT, Hartert TV. Rural health disparities in asthma care and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1220–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debbink MP, Bader MD. Racial residential segregation and low birth weight in Michigan's metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1714–1720. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iceland J, Sharp G, Timberlake JM. Sun belt rising: regional population change and the decline in black residential segregation, 1970–2009. Demography. 2013;50:97–123. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0136-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen M, Zhang X, Harris CD, Holt JB, Croft JB. Spatial disparities in the distribution of parks and green spaces in the USA. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(Suppl 1):S18–S27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eggleston PA, Rosenstreich DL, Lynn H, et al. Relationship of indoor allergen exposure to skin test sensitivity in inner-city children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:563–570. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donohue KM, Al-alem U, Perzanowski M, et al. Anti-cockroach and anti-mouse IgE are associated with early wheeze and atopy in an inner-city birth cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crain EF, Weiss KB, Bijur PE, Hersh M, Westbrook L, Stein REK. An estimate of the prevalence of asthma and wheezing among inner city children. Pediatr. 1994;94:356–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pesek RD, Vargas PA, Halterman JS, Jones SM, McCracken A, Perry TT. A comparison of asthma prevalence and morbidity between rural and urban schoolchildren in Arkansas. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins PS, Wakefield D, Cloutier MM. Risk factors for asthma and asthma severity in nonurban children in Connecticut. Chest. 2005;128:3846–3853. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry TT, Vargas PA, McCracken A, Jones SM. Underdiagnosed and uncontrolled asthma: findings in rural schoolchildren from the Delta region of Arkansas. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:375–381. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy SR, McGinty EE, Hayes SC, Zhang L. Regional and racial disparities in asthma hospitalizations in Mississippi. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph CL, Baptist AP, Stringer S, et al. Identifying students with self-report of asthma and respiratory symptoms in an urban, high school setting. J Urban Health. 2007;84:60–69. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9121-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph CLM, Peterson E, Havstad S, et al. A web-based, tailored asthma management program for urban African-American high school students. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:888–895. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1244OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiland SK, Bjorksten B, Brunekreef B, Cookson WO, von ME, Strachan DP. Phase II of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC II): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:406–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busse WW, Boushey HA, Camargo CA, Jr, Evans D, Foggs MB, Janson SL, et al. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; 2007. pp. 1–417. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph CL, Ownby DR, Havstad SL, et al. Evaluation of a web-based asthma management intervention program for urban teenagers: reaching the hard to reach. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010–2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503–509. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGrath RJ, Stransky ML, Seavey JW. The impact of socioeconomic factors on asthma hospitalization rates by rural classification. J Community Health. 2011;36:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AF, Huang B, Simmons JM, et al. Role of Financial and Social Hardships in Asthma Racial Disparities. Pediatr. 2014 doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bashir SA. Home is where the harm is: inadequate housing as a public health crisis. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:733–738. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Northridge J, Ramirez OF, Stingone JA, Claudio L. The role of housing type and housing quality in urban children with asthma. J Urban Health. 2010;87:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph CLM, Ownby DR, Peterson EL, Johnson CC. Racial differences in physiologic parameters related to asthma among middle-class children. Chest. 2000;117:1336–1344. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph CLM, Ownby DR, Peterson EL, Johnson CC. Does low birth weight help to explain the increased prevalence of asthma among African-Americans? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88:512. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeatts K, Davis KJ, Sotir M, Herget C, Shy C. Who gets diagnosed with asthma? Frequent wheeze among adolescents with and without a diagnosis of asthma. Pediatr. 2003;111:1046–1054. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magzamen S, Tager IB. Factors related to undiagnosed asthma in urban adolescents: a multilevel approach. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph CL, Baptist AP, Stringer S, et al. Identifying students with self-report of asthma and respiratory symptoms in an urban, high school setting. J Urban Health. 2007;84:60–69. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9121-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Prevalence Data: 1999–2010 Tables and Graphs. Atlanta, Georgia: 2014. Anonymous. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.