Abstract

Objective

To derive and validate a predictive model and novel Emergency Medical Services (EMS) screening tool for severe sepsis (SS).

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

A single EMS system and an urban, public hospital.

Patients

Sequential adult, non-trauma, non-arrest, at-risk, EMS-transported patients between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012. At-risk patients were defined as having all 3 of the following criteria present in the EMS setting: heart rate >90bpm, 2) respiratory rate >20bpm, and 3) systolic blood pressure <110mmHg.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Among 66,439 EMS encounters, 555 met criteria for analysis. Fourteen percent (n=75) of patients had SS, of which 19% (n=14) were identified by EMS clinical judgment. In-hospital mortality for patients with SS was 31% (n=23). Six EMS characteristics were found to be predictors of SS: older age, transport from nursing home, Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) 9-1-1 chief complaint category of “Sick Person”, hot tactile temperature assessment, low systolic blood pressure, and low oxygen saturation. The final predictive model showed good discrimination in derivation and validation subgroups (AUC 0.843 and 0.820, respectively). Sensitivity of the final model was 91% in the derivation group and 78% in the validation group. At a pre-defined threshold of 2 or more points, prehospital severe sepsis (PRESS) score sensitivity was 86%.

Conclusions

The PRESS score is a novel EMS screening tool for SS that demonstrates a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 47%. Additional validation is needed before this tool can be recommended for widespread clinical use.

MeSH Keywords: Sepsis, Critical Care, Emergency Medical Services

Introduction

Early recognition of severe sepsis is of paramount importance in order to facilitate timely initiation of life-saving treatment. The goal of early recognition is supported by the most recent Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines as a means of maximizing mortality benefit, primarily from early antibiotics and intravenous fluid therapy [1–3]. Despite best care practices, however, severe sepsis mortality remains as high as 18–30% [3, 4]. Notably, the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) care setting is a critical healthcare access point for up to 40–50% of patients with severe sepsis [5]. However, there are currently no standardized, evidence-based screening tools available to enable EMS providers to accurately recognize severe sepsis in the field. This recognition is a crucial first step to the provision of both supportive and definitive therapy. As the point of first medical contact, EMS recognition has the potential to positively impact patient outcomes by allowing for the development of coordinated care systems that facilitate earlier treatment in the Emergency Department (ED). Notably, this type of strategy has proven beneficial for other life-threatening, time-sensitive conditions including cardiac arrest, heart attack, stroke, and trauma [6–8].

Small studies suggest that EMS recognition of severe sepsis may be beneficial in reducing time to initiation of antibiotic and intravenous fluid administration [9, 10]. However, these reports have utilized screening tools that demonstrate low sensitivity to rule out sepsis, have not been formally validated, or require point-of-care diagnostic testing such as point-of-care venous lactate that is not readily available to most EMS providers [10–12]. In addition, the need for a practical, reliable EMS screening tool is highlighted by the finding that EMS clinical judgment is only 17% sensitive for recognizing severe sepsis [12]. This can likely be explained by a variety of factors, most important of which are the absence of a validated EMS screening tool, protocols derived from them, the complex, dynamic, and heterogeneous nature of the sepsis syndrome, and the low-resource nature of ambulances.

A practical, reliable EMS screening tool would not only allow earlier recognition of this life-threatening condition but would also enable further hypothesis testing that EMS recognition and coordinated EMS-ED care delivery systems improve sepsis outcomes through expediting definitive treatment. The aim of this study was to develop a simple, reliable EMS screening tool to aid first responders in detecting severe sepsis. As such, we herein report the derivation and validation of the prehospital severe sepsis (PRESS) score.

Methods

Study design and patient population

A retrospective cohort study of all adult patients (age ≥ 18) transported by Grady EMS to Grady Memorial Hospital was conducted between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012. All patients met a priori criteria for being at-risk of having sepsis. The at-risk group was defined in order to both enrich the study population and to reflect the practical realities of how a severe sepsis screening tool might be utilized. This approach is recommended when creating a predictive model and is similar to the approach utilized by EMS providers in screening patients for stroke and heart attack, for example [13]. In these situations, screening is not performed on every EMS patient but rather is triggered by the presence of at-risk features such as unilateral weakness or chest pain, respectively.

Patients were defined as being at-risk if all 3 of the following criteria were present in the EMS setting: heart rate (HR) >90bpm, 2) respiratory rate (RR) >20bpm, and 3) systolic blood pressure (SBP) <110mmHg. At-risk criteria were chosen based on modified systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and previously published reports of the association between low EMS systolic blood pressure and acute illness [1, 14].

Patients were excluded if any of the following conditions were identified by Emergency Medical Dispatch call takers or by EMS initial impression on-scene: trauma injury, cardiac arrest, pregnancy, psychiatric emergency or toxic ingestion. Exclusion criteria were based on: 1) existence of mature care pathways for the condition, 2) a low likelihood of severe sepsis being present, or 3) if the condition is not treated in the main Grady Emergency Department. Patients were also excluded if the EMS patient care record could not be linked to a corresponding hospital encounter.

Study setting

Grady EMS manages the Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) of 9-1-1 medical calls for the portion of the City of Atlanta located in Fulton County, Georgia (88% of the City’s population). Of approximately 74,000 annual ambulance transports by Grady EMS, approximately 30,000 are transported to Grady Memorial Hospital, a 900-bed, urban, public hospital. EMD call takers use an integrated software system, ProQA (version 3.4.3.33; Priority Dispatch Corporation; Salt Lake City, Utah), to query callers as well as categorize and prioritize caller information [15]. EMD complaint categories are generated by caller answers to scripted questions supplied by the standardized EMD protocol set. The “Sick Person” category is a standard classifier in the ProQA cardset and software system which is defined by Priority Dispatch as “a patient with a non-categorizable chief complaint who does not have an identifiable priority symptom” [15]. Please see Appendix 1 for a list of “Sick Person” non-priority complaints.

Grady EMS ambulances are staffed with basic life support emergency medical technicians and advanced life support paramedics. The level of expertise for a given response is based on the acuity of the complaint, as provided by the caller. Information routinely captured during the on-scene evaluation and treatment phase of EMS care includes a chief complaint-based patient history, an initial EMS impression, routine vital signs, physical examination and a summary clinical impression by EMS providers. The guidelines for arriving at these impressions are protocol-driven. Although temperature is not routinely measured, tactile temperature assessment is performed. EMS tactile temperature assessment has been shown to correlate with first measured, core temperature in the ED [16].

Data abstraction

EMS and hospital electronic medical records were manually linked based on the following criteria: date and time of encounter, patient name and date of birth. The presence of two out of three criteria was required for patient inclusion. Cases that could not be linked by the defined criteria were excluded. Data abstraction was performed by trained abstractors who were overseen by a lead abstractor (C.P.). The abstractors followed procedures outlined in the study operations manual. Random audit of 5% of all abstracted charts were performed by the lead abstractor to ensure at least 95% consistency with the operations manual procedures.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was an inpatient diagnosis of severe sepsis, including septic shock, within the first 48 hours of hospital arrival. The time cutoff was selected in order to exclude cases of hospital-acquired severe sepsis. Chart review was performed for each subject, and severe sepsis was defined as present if “severe sepsis” or “septic shock” was listed as a diagnosis in the clinical documentation of the inpatient care team [1, 17–19]. EMS and hospital demographics, biologic and physiologic data, admission diagnoses, and hospital outcomes were collected for each patient.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and entered into REDCap, an online, HIPAA-compliant database. For descriptive analysis, median values with interquartile ranges are reported. Student’s t test and Chi-square (or Fisher’s exact) tests were used as appropriate to report differences in means and proportions, respectively. Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to determine goodness-of-fit of the model.

To derive and validate the predictive model, the cohort was divided into derivation (80%) and validation (20%) subgroups using a random number generator [20]. To build the predictive model, univariable logistic regression analysis was performed on EMS variables consistent with potential predictors of severe sepsis. Variables were chosen for univariable analysis based on biologic plausibility, or if there was a significant difference in the distribution of patients with and without severe sepsis. Infectious signs and symptoms were grouped into a composite category consisting of reported fever, cough or infection due to small sample size of individual symptoms and instability in the model when symptoms were run individually. Shock, respiratory failure and respiratory arrest were grouped into a composite risk factor for the same reason. Seizure was not modeled as a risk factor due to model instability.

Variables associated with a p-value <0.10 were retained in a multivariable model, and variables associated with a p-value <0.05 were retained in the final predictive model. Stepwise selection procedures were used to further evaluate the final predictive model. We used cross validation techniques to assess the appropriateness of our model. These techniques changed the number of predictors from 6 to 5, but did not result in significant change in the point estimates. The final model was tested in both derivation and validation subgroups to determine performance characteristics including sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, both positive and negative. A risk classification table generated from the model was reviewed in order to select a highly sensitive cut point for risk classification [21]. This strategy was chosen in order to minimize the number of false negative sepsis screens. However, this strategy also unavoidably increases the number of false positive screens, a common characteristic of screening tests.

Using a previously described method, based on point estimate-weighted values for each predictor, the predictive model was converted into a prehospital severe sepsis clinical risk prediction score (PRESS) [22]. A highly sensitive point threshold was chosen to classify patients as low or increased risk for having severe sepsis [22]. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, North Carolina).

Study approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Emory Emergency Medicine Departmental Review Committee, the Emory Institutional Review Board, and the Grady Research Oversight Committee.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

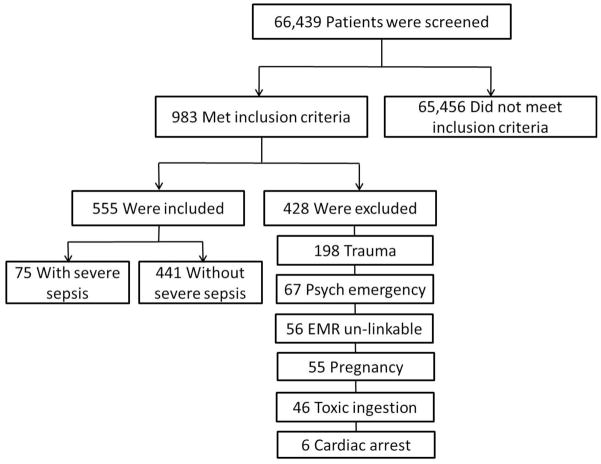

Among 66,439 EMS transports to Grady Memorial Hospital between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012, 555 met entry criteria, of which 13.5 % (n=75) had severe sepsis (Figure 1). Fourteen of 75 (19%) patients with severe sepsis were accurately identified by EMS providers. Baseline characteristics of patients with and without severe sepsis were compared (Table 1). Patients with severe sepsis were older (56 vs. 50 years, p=0.002), more likely to have a history of stroke (21% vs. 6%, p<0.0001), and less likely to have a history of asthma (9% vs. 21%, p=0.02).

Figure 1. Patient Selection†.

Definitions: EMR – Emergency Medical Record. † Inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18, EMS systolic blood pressure <110 mmHg, EMS heart rate >90 bpm, EMS respiratory rate >20bpm

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients with severe sepsis (N=75) | Patients without severe sepsis (N=480) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years, mean (SD) | 56 (15) | 49 (16) | 0.002 |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 35 (47) | 252 (53) | 0.35 |

| Race and ethnicity – no. (%) | 0.57 | ||

| Caucasian | 8 (11) | 33 (7) | |

| African-American | 63 (84) | 417 (87) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (1) | 14 (3) | |

| Other | 3 (4) | 16 (3) | |

| Medical history – no. (%) | |||

| Cardiac | 9 (12) | 100 (21) | 0.07 |

| Hypertension | 31 (41) | 182 (38) | 0.57 |

| Diabetes | 16 (21) | 93 (19) | 0.69 |

| Stroke | 16 (21) | 30 (6) | <0.0001 |

| Seizure | 9 (12) | 52 (11) | 0.76 |

| Asthma | 7 (9) | 102 (21) | 0.02 |

| COPD | 4 (5) | 40 (8) | 0.37 |

| CKD | 5 (7) | 26 (5) | 0.66 |

| Hemodialysis | 4 (5) | 21 (4) | 0.71 |

| Cancer | 8 (11) | 49 (10) | 0.90 |

| HIV/AIDS | 11 (15) | 59 (12) | 0.56 |

Definitions: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD – chronic kidney disease; HIV/AIDS – human immunodeficiency virus / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

EMS characteristics of patients are listed in Table 2. Patients with severe sepsis were more likely to have been categorized by medical dispatch as a “Sick Person” (40% vs. 16%, p<0.0001) and to have been transported from a nursing home (29% vs. 6%, p<0.0001). Patients with severe sepsis were also more likely to have had a hot tactile temperature (36% vs. 21%, p<0.0001), lower systolic blood pressure [(90mmHg (IQR 83–98) vs. 100mmHg (IQR 90–106), p<0.0001)], higher heart rate [123 (IQR 112–140) vs. 114 (IQR 104–130), p=0.01], lower oxygen saturation [92% (IQR 87–96) vs. 96% (IQR 92–99), p<0.0001)] and lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [(14 (IQR 9–15) vs. 15 (IQR 14–15), p<0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 2.

EMS Characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients with severe sepsis (N=75) | Patients without severe sepsis (N=480) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMD chief complaint category – no (%) | |||

| Chest pain | 4 (5) | 58 (12) | 0.08 |

| Cardiac symptoms | 1 (1) | 7 (2) | 1.00 |

| Difficulty in breathing | 17 (23) | 161 (34) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes-related complaint | 2 (3) | 23 (5) | 0.56 |

| Stroke | 1 (1) | 9 (2) | 1.00 |

| Unconscious | 9 (12) | 38 (8) | 0.24 |

| Seizure | 4 (5) | 39 (8) | 0.40 |

| Sick person | 30 (40) | 79 (16) | <0.0001 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (4) | 15 (3) | 0.72 |

| Hemorrhage | 2 (3) | 21 (4) | 0.76 |

| Other | 2 (3) | 29 (6) | 0.24 |

| Transport from location – no (%) | |||

| Residence | 43 (57) | 330 (69) | 0.05 |

| Nursing home | 22 (29) | 29 (6) | <0.0001 |

| Other | 7 (9) | 99 (21) | 0.02 |

| Not documented | 1 (1) | 12 (3) | 1.00 |

Definitions: EMD – Emergency Medical Dispatch. All dispatch categories were defined and determined by use of Priority Dispatch Corporation software.

Table 3.

EMS Vital Signs

| Characteristic | Patients with severe sepsis (N=75) | Patients without severe sepsis (N=480) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tactile temperature – no. (%) | |||

| Hot | 27 (36) | 56 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Normal | 38 (51) | 358 (76) | <0.0001 |

| Cool | 9 (12) | 55 (12) | 0.92 |

| Cold | 1 (1) | 5 (1) | 0.59 |

| SBP – mmHg, median (IQR) | 90 (83–98) | 100 (90–106) | <0.0001 |

| HR – bpm, median (IQR) | 123 (112–140) | 114 (104–130) | 0.01 |

| RR – bpm, median (IQR) | 26 (22–30) | 24 (22–28) | 0.07 |

| O2 saturation - %, median (IQR) | 92 (87–96) | 96 (92–99) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose – mg/dL, median (IQR) | 134 (94–165) | 123 (102–168 | 0.70 |

| GCS – median (IQR) | 14 (9–15) | 15 (14–15) | <0.0001 |

Definitions: SBP – systolic blood pressure; HR – heart rate; RR – respiratory rate; GCS – Glascow Coma Scale; IQR – interquartile range

The following initial EMS impression categories were more frequently documented in patients with severe sepsis: respiratory failure or arrest (4% vs. 0.4%, p=0.02), shock (4% vs 0.6%, p=0.04), acutely altered mental status or unconscious status (28% vs. 11%, p<0.0001), and a composite category of fever, infection or cough (15% vs. 8%, p=0.04) (Table 4). The following initial EMS impression categories were more frequently documented in patients without severe sepsis: chest pain (1% vs 11%, p=0.01), asthma (0% vs. 7%, p=0.01), and seizure (0% vs. 8%, p=0.01).

Table 4.

Initial EMS Impression

| Impression | Patients with severe sepsis (N=75) | Patients without severe sepsis (N=480) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure or arrest | 3 (4) | 2 (0.4) | 0.02 |

| Shock | 3 (4) | 3 (0.6) | 0.04 |

| Chest pain | 1 (1) | 53 (11) | 0.01 |

| Difficulty in breathing | 14 (19) | 87 (18) | 0.91 |

| Asthma | 0 (0) | 34 (7) | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary edema | 0 (0) | 8 (2) | 0.60 |

| Abdominal pain | 7 (9) | 28 (6) | 0.30 |

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | 2 (3) | 19 (4) | 0.75 |

| Stroke | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Altered or LOC | 21 (28) | 52 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Seizure | 0 (0) | 36 (8) | 0.01 |

| Dehydration | 3 (4) | 20 (4) | 1.00 |

| Dizzy or weak | 9 (12) | 28 (6) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 3 (4) | 31 (6) | 0.60 |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (1) | 16 (3) | 0.71 |

| Fever | 3 (4) | 6 (1) | 0.11 |

| Infection | 8 (11) | 29 (6) | 0.14 |

| Cough | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Fever, infection, cough | 11 (15) | 36 (8) | 0.04 |

| Other | 1 (1) | 42 (9) | 0.03 |

| Not Documented | 1 (1) | 7 (1) | 1.00 |

Definitions: LOC – loss of consciousness

In-hospital mortality for patients with severe sepsis was 31% (n=23) as compared to 5% (n=25) for those without severe sepsis (p<0.0001).

Development and Validation of the Predictive Model

Using univariable logistic regression analysis, the following variables were found to be significant predictors of severe sepsis in the derivation subgroup: older age modeled in tertiles, absent medical history of asthma, medical history of stroke, transport from nursing home, EMD chief complaint category of “Sick Person”, initial EMS impression of a composite of shock, respiratory failure or arrest, initial EMS impression of acutely altered mental status or unconscious state, hot tactile temperature assessment, low systolic blood pressure, elevated heart rate, elevated respiratory rate, low oxygen saturation, and low GCS (Table 5).

Table 5. Univariable Logistic Regression.

Univariable Analysis (N=441)†

| Predictor variable | Odds Ratio (95% CL) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age – (tertiles) | ||

| <40 | Reference | -- |

| 50–59 | 7.65 (2.30–25.45) | <0.001 |

| ≥60 | 6.73 (1.92–23.52) | <0.01 |

| Sex (M:F) | 1.36 (0.78–2.39) | 0.28 |

| Race (AA:C) | 0.81 (0.30–2.21) | 0.51 |

| Medical History | ||

| Asthma (Y/N) | 0.33 (0.13–0.86) | 0.02 |

| Stroke (Y/N) | 5.10 (2.39–10.91) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer (Y/N) | 1.31 (0.56–3.11) | 0.53 |

| HIV (Y/N) | 0.96 (0.41–2.23) | 0.92 |

| Diabetes (Y/N) | 1.44 (0.75–2.77) | 0.28 |

| EMS Characteristics | ||

| Nursing home transport (Y/N) | 8.87 (4.30–18.29) | <0.0001 |

| EMD chief complaint | ||

| DIB (Y/N) | 0.70 (0.37–1.31) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes (Y/N) | 0.90 (0.20–4.02) | 0.88 |

| Sick person (Y/N) | 3.32 (1.84–6.01) | <0.0001 |

| Altered or LOC (Y/N) | 0.96 (0.32–2.85) | 0.94 |

| Initial EMS impression | ||

| Shock, RF or arrest (Y/N) | 7.17 (1.74–29.53) | 0.006 |

| DIB (Y/N) | 1.37 (0.70–2.69) | 0.35 |

| Diabetes (Y/N) | 0.70 (0.16–3.08) | 0.64 |

| Altered or LOC (Y/N) | 2.91 (1.49–5.68) | 0.002 |

| Fever, cough, infection (Y/N) | 2.30 (0.87–4.62) | 0.11 |

| EMS Vital Signs | ||

| Hot tactile temp (Y/N) | 3.81 (2.02–7.18) | <0.0001 |

| SBP – per 1 mmHg increase | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | <0.0001 |

| HR - per 1 bpm increase | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.02 |

| RR – per 1 bpm increase | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.046 |

| Oxygen saturation – per 1 % inc. | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | <0.0001 |

| Blood glucose – per 1 mg/dL inc. | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.12 |

| GCS – per 1 point increase (3–15) | 0.86 (0.80–0.92) | <0.0001 |

Definitions: HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; DIB – difficulty in breathing; EMD – Emergency Medical Dispatch; RF – respiratory failure; LOC – loss of consciousness; SBP – systolic blood pressure; HR – heart rate; RR – respiratory rate; GCS – Glascow Coma Scale; CL – confidence limit.

Analysis performed in the derivation subgroup.

All variables modeled as binary categorical predictors (1-present; 0-absent) unless otherwise stated. Sex modeled as male vs. female (reference); race modeled African-American vs. Caucasian (reference). Age, SBP, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, GCS and blood glucose modeled as continuous variables.

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, the following predictors remained significant: older age modeled in tertiles, transport from nursing home, EMD chief complaint category of “Sick Person”, hot tactile temperature, low SBP, and low oxygen saturation (Table 6). These predictors were retained for the final predictive model (Table 7).

Table 6. Multivariable Logistic Regression.

Multivariable Analysis (N=441)†

| Predictor variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CL | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (tertiles) | |||

| <40 | Ref | -- | -- |

| 50–59 | 3.83 | 1.05–14.07 | 0.04 |

| ≥60 | 1.63 | 0.39–6.75 | 0.50 |

| Medical History | |||

| Asthma (Y/N) | 0.45 | 0.14–4.41 | 0.17 |

| Stroke (Y/N) | 1.88 | 0.65–5.43 | 0.24 |

| EMS Characteristics | |||

| Nursing home transport (Y/N) | 4.47 | 1.77–11.25 | <0.01 |

| EMD dispatch complaint | |||

| Sick person (Y/N) | 2.46 | 1.12–5.40 | 0.03 |

| Initial EMS impression | |||

| Shock, RF or arrest (Y/N) | 0.61 | 0.05–6.76 | 0.68 |

| Altered or LOC (Y/N) | 1.49 | 0.55–4.03 | 0.43 |

| EMS Vital Signs | |||

| Hot tactile temp (Y/N) | 2.52 | 1.10–5.74 | 0.03 |

| SBP – per 1 mmHg increase | 0.96 | 0.94–0.99 | <0.01 |

| HR - per 1 bpm increase | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.92 |

| RR – per 1 bpm increase | 0.98 | 0.92–1.05 | 0.61 |

| Oxygen saturation – per 1% inc. | 0.94 | 0.90–0.99 | 0.01 |

| GCS – per 1 point inc. (3–15) | 0.98 | 0.87–1.11 | 0.77 |

Definitions: EMD – Emergency Medical Dispatch; RF – respiratory failure; LOC – loss of consciousness; SBP – systolic blood pressure; HR – heart rate; RR – respiratory rate; GCS – Glascow Coma Scale; CL – confidence limit.

Analysis performed in the derivation subgroup.

All variables modeled as binary categorical predictors unless otherwise stated. Sex modeled as male vs. female (reference); race modeled African-American vs. Caucasian (reference). Age, SBP, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, GCS and blood glucose

Table 7.

Final Predictive Model (N=441)

| Predictor Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CL | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – (tertiles) | |||

| <40 | Ref | -- | -- |

| 50–59 | 4.28 | 1.20–15.38 | 0.03 |

| ≥60 | 2.19 | 0.56–8.66 | 0.26 |

| Nursing home transport (Y/N) | 4.73 | 2.01–11.13 | <0.001 |

| EMD complaint: sick person (Y/N) | 3.04 | 1.45–6.37 | <0.01 |

| Hot tactile temperature (Y/N) | 2.90 | 1.35–6.23 | <0.01 |

| SBP – per 1 mmHg increase | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | <0.01 |

| O2 saturation – per 1% increase | 0.95 | 0.91–0.99 | <0.01 |

Definitions: EMD – Emergency Medical Dispatch; SBP – systolic blood pressure; CL – confidence limit

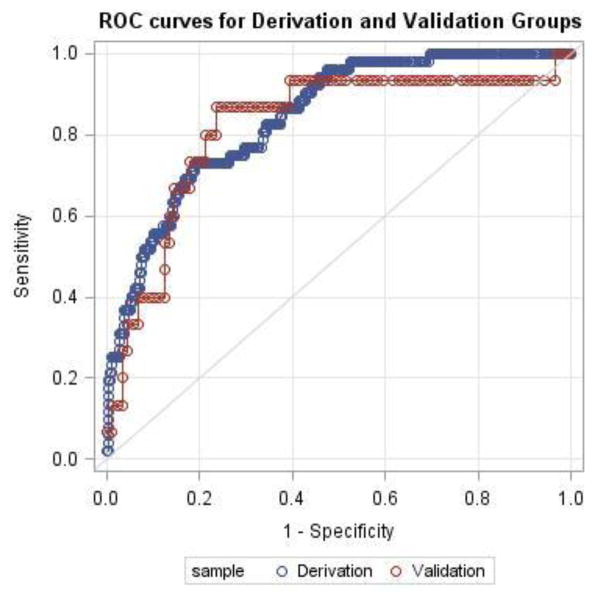

In the final model, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test demonstrated good model fit (Chi-square statistic 6.34; p=0.61). Performance characteristics of the model were determined in both the derivation and validation subgroups (AUC derivation 0.843; AUC validation 0.820) (Figure 2). Using a highly sensitive cut point of predicted probability >3%, the sensitivity and specificity were measured in both the derivation and validation groups and are reported in Table 8.

Figure 2. ROC Curves for Derivation and Validation Subgroups*.

Definitions: ROC – receiver-operating characteristic; AUC – area under curve

*AUC derivation – 0.843; AUC validation 0.820

Table 8.

Performance Characteristics of the Predictive Model and PRESS Score

| Characteristic | Model Derivation (N=441) | Model Validation (N=114) | PreSS Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 91% | 78% | 86% |

| Specificity | 34% | 26% | 47% |

| Positive predictive value | 17% | 16% | 19% |

| Negative predictive value | 96% | 86% | 96% |

Development of the PreSS Score

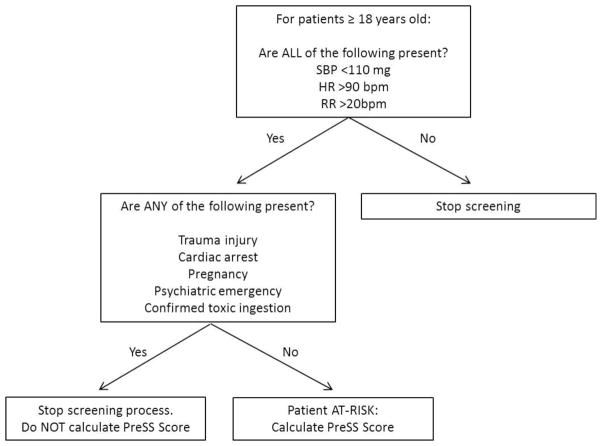

The predictive model was used to generate the PreSS score and an estimate of points-based risk using the same 6 risk factors used in the model: an Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) chief complaint category of “Sick Person”, EMS transport from a nursing home, older patient age, hot tactile temperature assessment, lower systolic blood pressure and lower oxygen saturation. The PreSS score demonstrated a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 47% (Table 8). A pre-screening flow sheet and final PreSS score sheet can be seen in Figure 3 and Table 9, respectively.

Figure 3. Pre-screening Flow Sheet.

Definitions: SBP – systolic blood pressure; HR – heart rate; RR – respiratory rate

Table 9.

Prehospital Severe Sepsis (PreSS) Score

| Risk Factor | Points |

|---|---|

| 1. EMD chief complaint: sick person | 3 |

| 2. Nursing home transport | 4 |

| 3. Age | |

| 18–39 | 0 |

| 40–59 | 4 |

| >=60 | 2 |

| 4. Hot tactile temperature | 3 |

| 5. Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |

| 100–109 | 0 |

| 90–99 | 1 |

| 80–89 | 2 |

| 70–79 | 3 |

| 60–69 | 4 |

| <60 | 5 |

| 6. Oxygen saturation (%) | |

| ≥ 90 | 0 |

| 80–89 | 1 |

| 70–79 | 3 |

| 60–69 | 4 |

| <60 | 5 |

| Total Points (0–24): | |

| ≥2 points = increased risk for severe sepsis | |

Definitions: EMD – Emergency Medical Dispatch

Discussion

The prehospital severe sepsis (PRESS) screening tool is simple, practical, and reliable and demonstrates a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 47%. One of the advantages of the PreSS score is that it is comprised of various types of routinely and practically collected EMS data including the following 6 risk factors: an EMD chief complaint category of “Sick Person”, EMS transport from a nursing home, older patient age, hot tactile temperature assessment, low systolic blood pressure and low oxygen saturation.

The potential impact of EMS recognition of severe sepsis is considerable. Just as EMS identification of STEMI allows for coordinated care that is streamlined to achieve the goal of door-to-balloon times of less than 90 minutes, EMS recognition of severe sepsis could potentially allow for shortened door-to-antibiotic times that maximize benefit to patients. The effectiveness of targeting other time-sensitive treatments including intravenous fluids and early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) is unknown [23, 24]. Diagnostic challenges currently limit prehospital identification of severe sepsis, arguably resulting in delay of initiation of life-saving treatment. In fact, a recent epidemiologic study showed that although the average prehospital care interval was greater than 45 minutes for EMS patients with severe sepsis, only 37% received prehospital intravenous access [5].

Small studies of EMS identification of severe sepsis have been shown to improve patient outcomes. In a study by Studek et al, severe sepsis patients who were identified by EMS had a shorter time to first antibiotics in the ER (70 vs 122 minutes, p=0.003) and a shorter time from ER triage to early goal-directed therapy initiation as compared to patients who were not identified by EMS (69 vs. 131 minutes, p=0.001) [9]. In another study by Guerra et al., EMS identification of severe sepsis using a tool that included point-of-care (POC) venous lactate was associated with an in-hospital mortality rate of 13.6% as compared to 50% in patients who were not identified or treated by EMS [10].

To our knowledge, three other EMS screening tools have been developed for severe sepsis [10–12]. They include: 1) the Guerra protocol that utilizes POC lactate, 2) the Robson screening tool, and 3) the BAS 90-30-90 [10–12]. These screening tools are arguably suboptimal for a variety of reasons. In a small, pilot study, the Guerra protocol demonstrated low sensitivity of 48%, and is also limited by the fact that POC lactate is not currently available in most EMS systems, including ours. The Robson screening tool was first described as a perspective piece in 2009 by Robson et al and is an adaptation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign diagnostic criteria [1, 11]. It utilizes modified systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, the presence of a suspected infection, and measures of end-organ dysfunction including systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, anuria, lactic acidosis, and prolonged bleeding from injury or gums. In a validation study, the Robson screening tool demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% but requires incorporation of data that may not be routinely available in most EMS settings. Finally, the BAS 90-30-90 is a tool recommended for use in Swedish EMS guidelines that uses 3 clinical indicators: systolic blood pressure <90mmHg, respiratory rate >30bpm, and oxygen saturation <90% [25, 26]. The BAS 90-30-90 tool has demonstrated a sensitivity of 81%, lower than that of the PRESS score.

Our study has several important limitations including its retrospective design. Although arguably the most suitable type of design that practically lends itself to building a large predictive model, it also introduces the potential for misclassification of disease. Misclassification may be present in our study because the primary outcome measure, diagnosis of severe sepsis, was determined using inpatient clinician diagnosis, rather than an independent review by an expert panel Although this definition has been utilized in previous studies, it is still possible that this method could result in missed cases of sepsis which would lead to a lower sensitivity of the screening tool [17–19]. The extent to which this potential limitation compromises the validity of our study is unknown.

Although validated internally, it is also noteworthy that our study was conducted at a single center which limits the external validity of our findings. The PRESS score will need to be validated in other populations before widespread application by 9-1-1 EMS services can be recommended. Finally, the PRESS score was developed from a pragmatic standpoint, in that, its use is not meant for use on all patients in the EMS setting. Although this should not be considered a limitation of the study, it is an important point of clarification to ensure appropriate use of the tool in the future. Specifically, all patients in our study had abnormal EMS vital signs (SBP <110, HR>90 and RR>20). Extrapolating use of the tool to all EMS patients would likely yield lower sensitivity and specificity than has been reported herein.

The PRESS score is a prehospital severe sepsis screening tool that has been both derived and validated using routinely collected EMS clinical data. Our hope is that future studies will test the potential benefit of pairing the PreSS score with early, EMS-appropriate interventions and hospital pre-arrival alert systems that facilitate rapid ED triage and resource allocation for these critically-ill patients.

Conclusion

The PRESS screening tool was derived and validated using routinely collected EMS data with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 47% has been derived and validated in this study. Additional validation studies are needed before this tool can be recommended for utilization in the public sphere by EMS services.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: C.P. and this work are supported by NIH T32GM095442 and UL1TR000454.

Appendix 1. Sick Person Non-Priority Complaints

Used by permission of the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch. ©2014 IAED. All rights reserved.

Appendix A.

| Sick Person Non-Priority Complaints Priority Dispatch ProQA© | |

|---|---|

| Blood pressure abnormality (asymptomatic) | Defecation/diarrhea |

| Dizziness/vertigo | Earache |

| Fever/chills | Enema |

| Generalized weakness | Gout |

| Nausea | Hemorrhoids/piles |

| New onset of immobility | Hepatitis |

| Other pain | Hiccups |

| Transportation only | Itching |

| Unwell/Ill | Nervous |

| Vomiting | Object stuck |

| Boils | Object swallowed |

| Bumps (non-traumatic) | Painful urination |

| Can’t sleep | Penis problems/pain |

| Can’t urinate | Rash/skin disorder |

| Catheter | Sexually transmitted disease |

| Constipation | Sore throat |

| Cramps/spasm/joint pain | Toothache |

| Cut-off ring request | Wound infected |

| Deafness | |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GS, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaieski DF, et al. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1167–74. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angus DC, et al. Protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1406745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seymour CW, et al. Severe sepsis in pre-hospital emergency care: analysis of incidence, care, and outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(12):1264–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0713OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Heart Rhythm A et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(5):e247–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jauch EC, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Emergency P et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Studnek JR, et al. The impact of emergency medical services on the ED care of severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(1):51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerra WF, et al. Early detection and treatment of patients with severe sepsis by prehospital personnel. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(6):1116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robson W, Nutbeam T, Daniels R. Sepsis: a need for prehospital intervention? Emerg Med J. 2009;26(7):535–8. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.064469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallgren UM, et al. Identification of adult septic patients in the prehospital setting: a comparison of two screening tools and clinical judgment. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):260–5. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trillo-Alvarez C, et al. Acute lung injury prediction score: derivation and validation in a population-based sample. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(3):604–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00036810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seymour CW, et al. Prehospital systolic blood pressure thresholds: a community-based outcomes study. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):597–604. doi: 10.1111/acem.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Academies of Emergency Dispatch (IAED) Medical Priority Dispatch Systems (MPDS) v12.2: Protocol 26 (Sick Person), ProQA Software v3.4.3.33. Priority Dispatch Corp; Salt Lake City, Utah, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson BPCC, Martin GS, Isakov A, Yancey A, Wilson D, Sevransky JE. Hot or not: does EMS tactile temperature correlate with core temperature and risk of sepsis? Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41:A261. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson DK, et al. Patient factors associated with identification of sepsis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(10):1280–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vishnupriya K, et al. Does sepsis treatment differ between primary and overflow intensive care units? J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):600–5. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sevransky JE, et al. Mortality in sepsis versus non-sepsis induced acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2009;13(5):R150. doi: 10.1186/cc8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picard RE, Berk KN. Data Splitting. The American Statistician. 1990;44(2):140–147. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson JMGaJG. Principles and practice of screening for diseae. World Health Organization Public Health Papers. 1968;34:1–163. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB., Sr Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: The Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med. 2004;23(10):1631–60. doi: 10.1002/sim.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pro CI, et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Investigators A, et al. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1496–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blomberg TJLAB. Treatment guidelines SLAS 2011. 2011 Available from: www.flisa.nu.

- 26.Council, S.C. Medical guidelines for the ambulance services in stockholm. 2012 Available from: http://www.webbhotell.sll.se/Global/prehospitala/dokument/Medicinska%20riktlinjer/Nyheter%20%20Ambulanssjukv%A5rdens%20behandlingsriktlinjer%202012.pdf.