Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a heterogeneous chronic inflammatory skin disease. Most AD during infancy resolves during childhood, but moderate to severe AD with allergic sensitization is more likely to persist into adulthood and more often occurs with other allergic diseases.

Objective

We sought to find susceptibility loci by performing the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) of AD in Korean children with recalcitrant AD, defined as moderate to severe AD with allergic sensitization.

Methods

Our study included 246 children with recalcitrant AD and 551 adult controls with a negative history of both allergic disease and allergic sensitization. DNA from these individuals was genotyped; sets of common SNPs were imputed and used in the GWAS after quality control checks.

Results

SNPs at a region on 13q21.31 were associated with recalcitrant AD at a genome-wide threshold of significance (P < 2.0×10−8). These associated SNPs are >1Mb from the closest gene, PCDH9. SNPs at four additional loci had P < 1×10−6, including SNPs at or near the NBAS (2p24.3), THEMIS (6q22.33), GATA3 (10p14) and SCAPER (15q24.3) genes. Further analysis of total serum IgE levels suggested 13q21.31 may be primarily an IgE locus, and analyses of published data demonstrated SNPs at the 15q24.3 region are expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) for two nearby genes, ISL2 and PSTPIP1, in immune cells.

Conclusion

Our GWAS of recalcitrant AD identified new susceptibility regions containing genes involved in epithelial cell function and immune dysregulation, two key features of AD, and potentially extend our understanding of their role in pathogenesis.

Keywords: genome-wide association study, atopic dermatitis, allergic sensitization, IgE, severity, children

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a complex chronic inflammatory skin disease that commonly presents during childhood, when it is strongly associated with allergic sensitization.1 Although AD has a varied disease course, children with moderate to severe AD with allergic sensitization are more likely to have disease persisting to adulthood and more concomitant allergic diseases, such as asthma or allergic rhinitis, which result in significant healthcare costs.2 Available treatment options for prevention and treatment of this subtype of recalcitrant AD are still insufficient,3 reflecting our poor understanding of disease pathogenesis.

AD is highly heritable, with heritability estimates of 72% in European twin pairs4,5 and genetic studies supporting a significant role for aberrant gene expression in AD.6 In particular, low frequency and rare loss-of-function variants in the filaggrin (FLG) gene are major predisposing factors for persistent AD, as well as for skin infections with AD and multiple allergic diseases.7–9 Filaggrin deficiency results in skin barrier dysfunction resulting in accelerated water loss, skin alkalinization and colonization by microbial pathogens.10 Based on these findings, epithelial barrier dysfunction (filaggrin, in particular) has been placed in the center of AD pathogenesis.

Three large genome-wide association studies (GWAS),11–13 a meta-analysis of GWAS from 16 population-based European cohorts14 and targeted studies using the immunochip15 have identified several candidate AD genes in addition to FLG. However, none reached genome-wide significance in the discovery samples and, moreover, there were no shared loci among the top associations in studies of European and Han Chinese AD populations.11,12 These combined results suggest genetic heterogeneity in AD between continental populations, particularly when broad case definitions are used. AD is characterized by genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity, and this is consistent with the finding susceptibility loci discovered to date, including FLG, account for only 14.4% of the heritability of AD in Europeans,15 and suggest studies in additional populations and narrower clinical definitions are needed to fully characterize the genetic architecture of AD.

Here, we conducted the first GWAS of AD in Korean children, and focus on the distinct phenotype of recalcitrant AD, defined as moderate to severe AD with allergic sensitization. Moreover, we included as controls non-allergic adults without history of allergic diseases. We identified a novel region of chromosome 13q21.31 as likely to contain genes controlling risk to AD which was genome-wide significant and additional loci including the NBAS, THEMIS, GATA3 and SCAPER genes as suggested genes for AD.

Methods

Sample compositions

Our study included 246 Korean children with both moderate to severe AD and allergic sensitization and 551 Korean adult controls without history of allergic diseases or evidence of allergic sensitization. In addition, because IgE levels vary with age, we performed association studies of selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with total serum IgE in the 246 case children and 108 healthy Korean children without allergic diseases or evidence of allergic sensitization where measured levels of total serum IgE as controls were available (Table S1). Children cases and controls were recruited from Severance children’s hospital, Seoul, Korea, and adult controls were from the Ansung population-based cohort (N = 5,108), which was established as part of the KoGES by Korea Center for Diseases Control and Prevention.16

Clinical evaluations

AD was diagnosed by pediatric allergists, based on the revised Hanifin and Rajka criteria.17 We first determined the severity using the Severity SCOring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index18 of 572 children, and then recruited 275 children cases with moderate to severe AD (SCORAD ≥ 30; mean ± SD, 59.9 ± 14.4) for our studies. Allergic sensitization was defined by specific IgE greater than 0.7 kUA/l to at least one of the following food or airborne allergens: egg white, milk, peanut, soybean, wheat, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p), Dermatophagoides farina (Der f), Alternatia or Blattella germanica. Of the 275 children with moderate to severe AD, 246 had specific IgE to at least one of the allergens. We selected 551 adult controls with a negative history of both allergic diseases and allergic sensitization among 1,214 adults. Negative histories of allergic diseases, including asthma and AD, were based on a self-administered questionnaire; lack of sensitization was based on a negative skin prick test result to 12 common allergens (Der p, Der f, 2 tree pollen mixtures, grass pollen mixture, ragweed, mugwort, cockroach, Alternaria, Aspergillus, cat dander and dog dander). Additionally, 108 control children were recruited during routine hospital visits and were included in our study if they had a negative history of allergic diseases based on interviews with their parents, were negative for serum specific IgE to 6 common allergens (egg white, milk, Der p, Der f, Alternatia or Blattella germanica) and had total serum IgE levels below 100 kU/l. All cases and controls were unrelated and either they or their parents provided written informed consent for themselves to participate in the study according to the Hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

Genotyping, imputation and quality control in the GWAS

Blood samples were collected from each participant and the derived genomic DNA was genotyped using the Affymetrix Axiom array in the AD and control children and the Affymetrix 5.0 chip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, Calif) in the adult controls (Table S1). We excluded samples with call rates for autosomal SNPs less than 95%, and excluded SNPs with minor allele frequencies less than 5% or Hardy-Weinberg P values less than 10−4. Quality control was performed using PLINK 1.07.19 After quality control exclusions, 402,919 SNPs remained in the children and 287,622 SNPs in the adults. The common sets of SNPs were then used for imputation using minimac20 and the 1000 Genomes Asian reference panel.21 The resulting genotype data for 14,598,181 SNPs were subjected to further quality control checks and selected for high imputation accuracy (r2 > 0.9) and minor allele frequency > 5%. As a final quality filter, SNPs were excluded if their allele frequencies differed (P ≥ 0.001) between the adult and children control samples. In the end, 2,501,352 autosomal SNPs were used for the GWAS analysis.

Association of most significant SNPs with total serum IgE levels

We tested 20 of the 53 SNPs with P < 10−6 in the GWAS of AD after pruning for LD (r2 > 0.8 in the Asian 1000 genomes data) for association with total serum IgE in 108 control children (Table S1). These studies were performed in non-allergic control children to determine if these variants were also associated with IgE independent of AD (Fig. S2).

Replication studies

To examine the association of SNPs with P value < 10−6 in our GWAS, we obtained P-values of those SNPs from a GWAS of AD in Japanese individuals (Table S1). That study included 1,472 cases with physician-diagnosed AD, and 7,966 controls including 6,042 subjects with one of five non-AD diseases (cerebral aneurysm, esophageal cancer, endometrial cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and glaucoma) and 1,929 healthy volunteers without history of asthma or AD.13

Gene expression and eQTL analysis

To determine whether the SNPs associated with AD in our GWAS were expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), we used the eQTL browser (GTEx, http://www.gtexportal.org/)22 and published reports from eQTL studies of different cell types, including skin,15,23–25 B-cells and monocytes,26,27 and of CD14+ monocytes stimulated with interferon-γ or lipopolysaccharide (LPS).28

Statistical Analysis

We performed logistic regression analysis for binary phenotypes (AD) and linear regression analysis for continuous phenotypes (total serum IgE) using R software an additive model. The statistical significance of the association with each SNP was assessed using a 1-degree-of-freedom Cochran-Armitage trend test. Regional association plots were generated using LocusZoom.29

Results

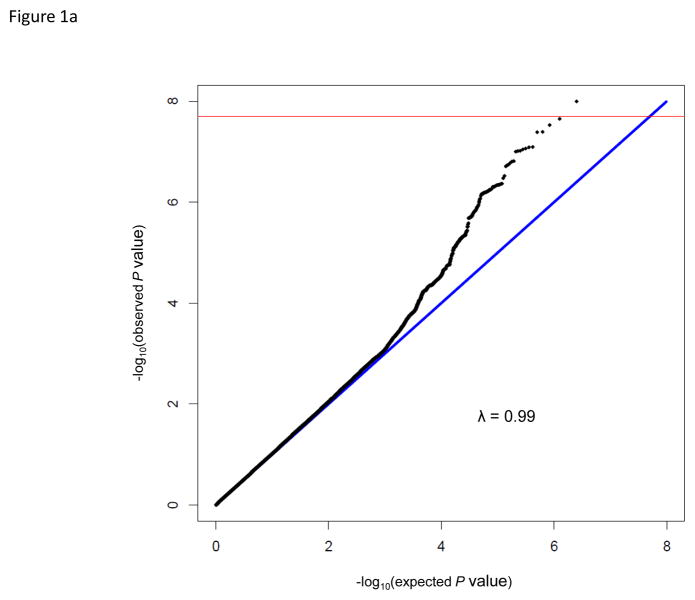

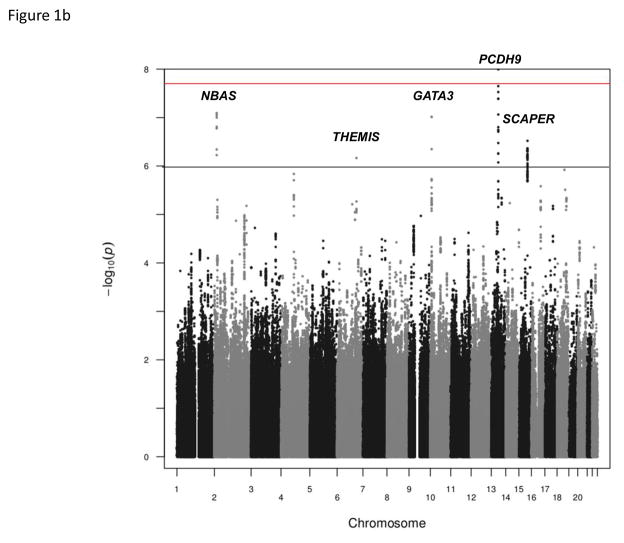

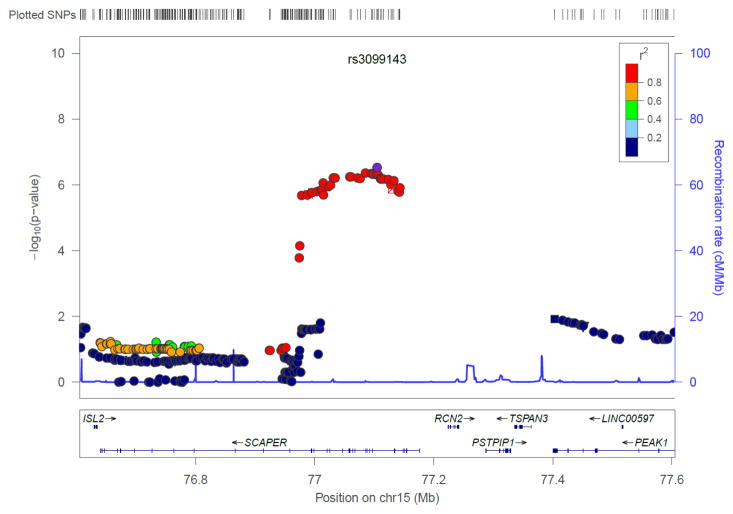

The GWAS of AD in 246 Korean children with moderate to severe AD and allergic sensitization and 551 Korean adults with a negative history of allergic diseases and no allergic sensitization showed an excess of small p-values compared to those expected by chance (Fig. 1a). One SNP (rs9540294) at 13q21.31 passed genome-wide threshold of significance (Bonferroni corrected P < 2.0 × 10−8); 13 additional SNPs at this region including PCDH20-PCDH9 were associated with moderate to severe AD with allergic sensitization at P< 1 × 10−6 (Fig. 1b, Fig. S1a). A total of 39 SNPs in four additional regions were also associated at P< 1 × 10−6: the NBAS gene at 2p24.3 (Fig. S1b), the THEMIS gene at 6q22.33 (Fig. S1c), the GATA3- CELF2 locus at 10p14 (Fig. S1d), and the SCAPER gene at 15q24.3 (Fig. 2). The most significant SNP at each locus is shown in Table 1; the results for SNPs at these six loci are shown in Table S2.

Figure 1.

(a) Quantile-quantile plot of P values for the test statistics (Cochran-Armitage trend tests) in the GWAS. Horizontal and vertical axes show expected P values under a null distribution and observed P values, respectively. Black data points correspond to the P values of all SNPs in the GWAS. (b) Manhattan plot showing the –log10 P values of 2,501,352 SNPs in the GWAS for 246 Korean children with recalcitrant atopic dermatitis and 551 Korean adult controls without a history of allergic diseases and allergic sensitization plotted against their respective positions on the autosomes. The red line shows the genome-wide significance threshold (P = 2.0 × 10−8). The gray line shows the threshold at P = 1 × 10−6. Locations of the NBAS (2p24.3), THEMIS (6q22.33), GATA3 (10p14), PCDH9 (13q21.31), SCAPER (15q24.3) loci are indicated.

Figure 2.

Regional association plots at the 15q24.3 locus for recalcitrant atopic dermatitis. Significant SNPs are located within the SCAPER gene and include cis-eQTLs for the ISL2 gene in whole blood and for PSTPIP1 in CD14+ monocytes after treatment with LPS for 24 hours. The –log10 P value (left y axis) of each SNP is shown according to its chromosomal position (x axis). Genetic recombination rates are shown by the blue line, and horizontal arrows indicate the locations of genes and direction of transcription. The most associated SNP (labeled by rs number) is shown as a purple circle, and its LD (r2) with all other SNPs is indicated by color.

Table 1.

Summary of GWAS of atopic dermatitis at P < 10−6 in Korean Children

| Genes or nearby genes | Location | SNP | Position | Alleles (risk/alt) | RAF (Case) | RAF (Control) | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBAS | 2p24.3 | rs13403179 | 15482752 | C/G | 0.131 | 0.054 | 8.07E-08 | 2.947 | (1.989–4.386) |

| THEMIS | 6q22.33 | rs675531 | 128040839 | C/T | 0.205 | 0.113 | 6.82E-07 | 2.193 | (1.610–2.994) |

| GATA3 | 10p14 | rs35766269 | 9023815 | A/T | 0.717 | 0.580 | 9.61E-08 | 1.946 | (1.529–2.494) |

| PCDH9 | 13q21.31 | rs9540294 | 65564031 | G/T | 0.181 | 0.083 | 1.01E-08* | 2.655 | (1.904–3.717) |

| SCAPER | 15q24.3 | rs3099143 | 77104856 | C/A | 0.239 | 0.137 | 3.02E-07 | 2.126 | (1.594–2.841) |

RAF, risk allele frequency; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The most significant SNPs at each locus are shown and ordered by genomic location.

P value exceeded the threshold for Bonferroni-corrected genome-wide significance (P < 2.0 × 10−8)

Because all the cases had both AD and allergic sensitization and the adult controls had neither, we utilized a second control group of non-allergic children with measured levels of total serum IgE to disentangle associations primarily with AD from those that are primarily with IgE levels (i.e., allergic sensitization). SNPs at the 13q21.31 locus showed suggestive evidence for association with serum total IgE in 108 control children (P < 0.05, Table 2). Thus, it is likely the association with AD at this region may be due to the significantly higher levels of IgE in the AD cases compared to non-allergic controls, and that the primary effects of this locus are on IgE production and not risk of AD per se.

Table 2.

Summary of results for most significant AD-associated SNPs with total serum IgE in Korean children controls

| Genes or nearby genes | Location | SNP | Position | Alleles (risk/alt) | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBAS | 2p24.3 | rs13398948 | 15481147 | A/G | 0.346 | 0.726 | (0.371–1.421) |

| rs75790198 | 15481366 | T/C | 0.351 | 0.729 | (0.372–1.423) | ||

| rs16862519 | 15481752 | T/C | 0.350 | 0.729 | (0.374–1.422) | ||

| rs13428288 | 15482611 | G/A | 0.354 | 0.731 | (0.375–1.424) | ||

| rs13403179 | 15482752 | C/G | 0.354 | 0.731 | (0.375–1.424) | ||

| rs147759857 | 15485351 | A/T | 0.354 | 0.731 | (0.375–1.424) | ||

| rs114663129 | 15486515 | T/C | 0.351 | 0.730 | (0.375–1.422) | ||

|

| |||||||

| THEMIS | 6q22.33 | rs675531 | 128040839 | C/T | 0.510 | 0.828 | (0.471–1.458) |

|

| |||||||

| GATA3 | 10p14 | rs35766269 | 9023815 | A/T | 0.569 | 1.100 | (0.790–1.532) |

|

| |||||||

| PCDH9 | 13q21.31 | rs7987130 | 65557327 | T/C | 0.005 | 2.433 | (1.314–4.505) |

| rs9540294 | 65564031 | G/T | 0.005 | 2.431 | (1.313–4.498) | ||

| rs9528865 | 65564293 | A/G | 0.305 | 1.256 | (0.810–1.948) | ||

| rs9540298 | 65567319 | T/C | 0.005 | 2.435 | (1.315–4.510) | ||

|

| |||||||

| SCAPER | 15q24.3 | rs141545456 | 77014367 | T/C | 0.422 | 1.215 | (0.752–1.963) |

| rs111406539 | 77076517 | C/T | 0.429 | 1.211 | (0.750–1.955) | ||

| rs1114717 | 77086078 | A/G | 0.424 | 1.213 | (0.753–1.953) | ||

| rs3099143 | 77104856 | C/A | 0.464 | 1.193 | (0.741–1.922) | ||

| rs3099140 | 77111012 | A/G | 0.423 | 1.211 | (0.756–1.939) | ||

| rs3099139 | 77112291 | G/A | 0.423 | 1.211 | (0.756–1.939) | ||

| rs3099138 | 77115524 | A/G | 0.423 | 1.210 | (0.756–1.937) | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

SNPs are ordered by genomic location.

SNPs were selected after LD pruning (r2> 0.8) using Asian 1000Genome genotypes from the 53 SNPs with P < 10−6 in GWAS results. No P value exceeded the threshold for Bonferroni-corrected significance (P < 2.5×10−3, 0.05/20).

To attempt replication of the SNPs identified in our GWAS of moderate to severe AD with allergic sensitization, we examined the results of the 53 SNPs yielding P < 10−6 in our study to a published GWAS in another Asian study comprised of Japanese adults, in which AD was diagnosed by physicians irrespective of severity or allergic sensitization population.13 None of the associations in the Korean children in our study replicated in the study of Japanese adults (Table S2).

We next examined in our study subjects SNPs loci associated with AD or IgE in previous GWAS. We detected modest associations (P < 0.05) with SNPs associated with AD at the IL2-IL21, RAD50-IL13, TMEM232-SLC25A46, KIF3A and ZNF365 loci, and with total serum IgE at the PTBP2, PEX14, IL2-ADAD1, PTGER4, TSLP, SLC25A46, RAD50, PCDH20, FOXA1-TTC6 and IL4R-IL21R loci (Table 3). Among these associations, four regions (4q27, 5q13, 5q22.1 and 5q31) have been previously reported in GWAS of both AD and IgE phenotypes. In addition, a SNP nearby PCDH20 gene at the 13q21.31 region was previously associated with IgE in a Japanese population,30 further suggesting 13q21.31 region might contain a gene controlling IgE levels.

Table 3.

Evidence of associations with atopic dermatitis or IgE phenotype in the Korean children for the previously reported loci

| Phenotype | Location | Gene | Previous report | Current study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| SNP | P value | Population | Reference | SNP | HapMap r2 | P value | |||

| Atopic dermatitis | 4q27 | IL2-IL21 | rs17389644 | 1.16E-06 | European | Ellinghaus D15 | rs17454584 | 1 | 0.038 |

| 5q22.1 | TMEM232-SLC25A46 | rs7701890 | 4.33E-08 | Chinese | Sun LD12 | rs10038233 | 0.863 | 0.025 | |

| 5q22.1 | TMEM232-SLC25A46 | rs10067777 | 6.32E-08 | Chinese | Sun LD12 | rs10035754 | 0.846 | 0.039 | |

| 5q22.1 | TMEM232-SLC25A46 | rs13361382 | 2.09E-07 | Chinese | Sun LD12 | rs10038233 | 0.863 | 0.025 | |

| 5q22.1 | TMEM232-SLC25A46 | rs13360927 | 2.80E-07 | Chinese | Sun LD12 | rs13360927 | - | 0.046 | |

| 5q31 | KIF3A | rs2897442 | 3.80E-08 | European | Paternoster L14 | rs2897442 | - | 0.002 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50 | rs2897443 | 8.95E-13 | European | Weidinger S52 | rs2897443 | - | 0.029 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50 | rs6871536 | 2.11E-15 | European | Weidinger S52 | rs6871536 | - | 0.028 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50-IL13 | rs2158177 | 5.90E-11 | European | Weidinger S52 | rs2706338 | 0.92 | 0.022 | |

| 10q21.2 | ZNF365 | rs2393903 | 1.05E-07 | Chinese | Sun LD12 | rs2393903 | - | 0.033 | |

|

| |||||||||

| IgE phenotype | 1p21.3 | PTBP2 | rs321588 | 2.05E-06 | Admixture | Levin AM53 | rs321588 | - | 0.003 |

| 1p36.22 | PEX14 | rs2056417 | 3.70E-07 | European | Hinds DA46 | rs2056417 | - | 0.029 | |

| 4q27 | IL2 | rs2069772 | 1.10E-06 | European | Ramasamy A54 | rs2069772 | - | 0.042 | |

| 4q27 | IL2-ADAD1 | rs17454584 | 5.50E-10 | European | Bonnelykke K55 | rs17454584 | - | 0.038 | |

| 4q27 | ADAD1 | rs17388568 | 3.90E-08 | European | Hinds DA46 | rs17388568 | - | 0.043 | |

| 5p13.1 | PTGER4 | rs7720838 | 8.20E-11 | European | Hinds DA46 | rs7720838 | - | 0.016 | |

| 5q22.1 | TSLP | rs1898671 | 9.00E-03 | European | Ramasamy A54 | rs1898671 | - | 0.006 | |

| 5q22.1 | SLC25A46 | rs10056340 | 5.20E-14 | European | Bonnelykke K55 | rs4259213 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50 | rs2706347 | 6.28E-07 | European | Weidinger S56 | rs2706347 | - | 0.026 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50 | rs3798135 | 6.69E-08 | European | Weidinger S56 | rs3798135 | - | 0.027 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50 | rs2040704 | 4.46E-08 | European | Weidinger S56 | rs2040704 | - | 0.030 | |

| 5q31.1 | RAD50 | rs7737470 | 3.35E-07 | European | Weidinger S56 | rs7737470 | - | 0.033 | |

| 13q21.31 | PCDH20 | rs1399315 | 6.40E-07 | Japanese | Yatagai Y30 | rs1399315 | - | 0.033 | |

| 14q21.1 | FOXA1-TTC6 | rs1998359 | 4.80E-08 | European | Hinds DA46 | rs9671863 | 1 | 0.042 | |

| 16p12.1 | IL4R-IL21R | rs2107357 | 3.30E-07 | European | Hinds DA46 | rs2107357 | - | 0.026 | |

SNPs are shown with P value < 0.05 and ordered by phenotype and genomic location.

If the reported SNP was not imputed in our data, a surrogate SNP with the strongest LD to the reported SNP and the amount of LD in Japanese HapMap (r2) are shown.

Finally, we asked whether the 53 SNPs associated with AD at P < 10−6 in our study, or SNPs in strong LD with these SNPs (r2=0.8), were also associated with the expression of nearby (± 1 Mb) genes (i.e., are cis-eQTLs) in relevant tissues.15,22–28 Five SNPs in strong LD at the 15q24.3 locus were cis-eQTLs for PSTPIP1 in primary CD14+ monocytes after LPS exposure (P = 1.8 × 10−5, Fig. 2),28 and were also cis-eQTLs for ISL2 in whole blood (P < 3.1 × 10−6, GTEx). SNPs at the other four AD-associated loci in our study were not reported as eQTLs in any published studies in skin or blood cells.

Discussion

AD is a heterogeneous disease1 with respect to the presence of allergic sensitization, levels of total serum IgE, predilection to skin lesions, and prognosis, which differ both between children and adults and among children and adults separately.2 It is likely that the genetic architecture also differs between phenotypic subtypes of AD. Yet, this heterogeneity was not considered in previous GWAS that included cases with physician-diagnosed AD without regard to severity or sensitization, and relied on population controls who were not screened for AD or allergic sensitization.11–13 We hypothesized that focusing on more severe AD in sensitized children would identify additional genes and pathways. To this end, we focused on an extreme phenotype by including only children with moderate to severe AD and allergic sensitization, and considered as controls adults without a current or prior history of allergic disease and lack of allergic sensitization. The stringent criteria resulted in a smaller sample than in previous GWAS of AD,11–14 yet we identified a new AD locus at genome-wide levels of significance on chromosome 13q and a second locus at 15q24.3 included SNPs that are eQTLs for two nearby genes in relevant cell types. Although associations with variants in the FLG gene have robust associations with AD, the low frequency and rare pathogenic mutations in FLG were not imputed in our study so we could not directly assess the effects of those variants or their interactions with genotypes at other associated loci AD in our study.

The most significant association in our GWAS was with SNPs on 13q21.31 (smallest P = 1.01 × 10−8). In previous studies, SNPs in this region were associated with asthma,31 rheumatoid arthritis,32 and total serum IgE.30 In fact, some of the most significant SNPs (P < 10−6) were also associated with serum total IgE in non-allergic controls (Table 2). The associated SNPs reside in a gene desert including six long intergenic non-protein coding (linc) RNAs and predicted regulatory elements (DNaseI hypersensitivity sites) in skin tissue from patients with malignant melamona or lymphoblast.33 The closest protein coding genes, PCDH9, is approximately 1.3 Mb and encodes a member of the nonclustered protocadherin family, a subgroup of the cadherin superfamily of cell adhesion proteins.34 Another member of the protocadherin family of genes, PCDH1, has been implicated in susceptibility to both AD35,36 and asthma.35,37,38 Nonetheless, our results extend earlier findings by potentially implicating other genes in the protocadherin family in AD pathogenesis.

We also observed associations with AD at suggestive levels of significance at four additional loci at 2p24.3, 6q22.33, 10p14 and 15q24.3. The NBAS gene at 2p24.3 encodes neuroblastoma amplified sequence (NBAS) whose expression has been associated with poor outcome in patients with neuroblastoma.39 NBAS protein is expressed in epidermal skin cell, although it has not previously been implicated in chronic skin inflammatory diseases.40 In contrast, genes at the 6q22.33, 10p14 and 15q24.3 locus are involved in immune dysregulation, which is a key pathogenic pathway in AD. The 6q22.33 and 10p14 loci include genes involved in adaptive immune responses, particularly in T cell differentiation. SNPs at the 6q22.33 locus were associated with autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s disease41 and multiple sclerosis.42 The THEMIS (thymus-expressed molecule involved in selection) gene at this locus encodes a molecule that “fine-tunes” positive and negative T-cell selection in the thymus,43 and its mutation has been reported to yield impaired function of regulatory T cells and skewed cytokine profile toward Th2 phenotypes in inflammatory bowel disease animal model.44 The associated locus at 10p14 resides between GATA3 and CELF2. SNPs at this locus were previously associated with rheumatoid arthritis,45 self-reported allergy,46 or asthma.47 GATA3 is the closest protein coding gene (approximately 900 Kb), which an important regulator of T cell development and promotes the secretion of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 from Th2 cells, which lead to allergic sensitization.48 This locus also includes predicted DNaseI hypersensitivity sites for GATA3 in various tissues or cell types including skin or Th2 cell.33 Of potential relevance is that allergen-specific GATA3 expression precedes clinical allergic sensitization,49 which might suggest GATA3 plays a role at the beginning of allergic inflammation. Moreover, our GWAS replicated the previous reported association with SNPs at the Th2 cytokine (RAD50-IL13-IL4) locus on 5q31.1 (Table 3). Taken together, we suggest these Th2 related loci represent excellent candidate regions for the inflammatory network of AD.

Finally, the associated SNPs at 15q24.3 are located within the SCAPER gene, which regulates cell cycle progression.50 Some of these SNPs are also cis-eQTLs for PSTPIP1 in CD14+ monocytes after treatment with LPS and for the ISL2 gene in whole blood.28 Because the latter results are from studies of mixed cells, we do not know if the eQTL is present in all leukocytes or just in a subset. Mutations in PSTPIP1 gene cause PAPA syndrome (Pyogenic Arthritis, Pyodermagangrenosum, and Acne), which is an autosomal dominant auto-inflammatory disease.51 In PAPA, PSTPIP1 induces the activation of the inflammasome involved in interleukin-1 production resulting in aberrant innate immune responses in the skin and joints.51 A primary feature of AD is skin inflammation, making this gene on 15q24.3 a logical functional candidate for moderate to severe AD in children.

To our knowledge, this is the first GWAS of AD in Koreans and the first GWAS of AD using extreme phenotypes in cases and unaffected individuals as controls. As a result, there are no available replication samples with the same phenotype or ethnicity as that used in our study. The lack of replication of our most significant SNPs may be due to different case definitions, differences between childhood and adult AD, different ancestries or some combination of these factors. Regardless, this GWAS in Korean children with moderate to severe AD and allergic sensitization identified new AD candidate genes related to epithelial cell function and immune dysregulation, two key features of AD. Further studies of these genes are required to both replicate the association with the distinct phenotype of recalcitrant AD and to better understand their role in pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

We report 5 new AD candidate genes through this GWAS in Korean children.

SNPs at the13q21.31 locus were associated with recalcitrant AD at genome-wide levels of significance, but this may be a primarily IgE locus.

GWAS of extreme phenotypes may reveal additional genes for AD.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This research was supported by the grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI11C1404, HI14C0234 and A092076), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2007-0056092), the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2010-0025171), and NIH grants U19 AI095230 and R01 HL085197 to C.O. This study included biospecimens and data from the Korean Genome Analysis Project (4845-301), the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (4851-302), and Korea Biobank Project (4851-307, KBP-2014-033) that were supported by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Republic of Korea.

We thank all of the subjects and families for their participation in the study, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments.

Abbreviations used

- AD

Atopic dermatitis

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SCORAD

Severity SCOring Atopic Dermatitis

- Der p

Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus

- Der f

Dermatophagoides farina

- eQTLs

expression quantitative trait loci

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- Linc

long intergenic non-protein coding

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garmhausen D, Hagemann T, Bieber T, Dimitriou I, Fimmers R, Diepgen T, et al. Characterization of different courses of atopic dermatitis in adolescent and adult patients. Allergy. 2013;68:498–506. doi: 10.1111/all.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenstein P, Svartengren M. Genes, environments, and sex: factors of importance in atopic diseases in 7–9-year-old Swedish twins. Allergy. 1997;52:1079–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nystad W, Roysamb E, Magnus P, Tambs K, Harris JR. A comparison of genetic and environmental variance structures for asthma, hay fever and eczema with symptoms of the same diseases: a study of Norwegian twins. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1302–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes KC. An update on the genetics of atopic dermatitis: scratching the surface in 2009. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:16–29. e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.008. quiz 30–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAleer MA, Irvine AD. The multifunctional role of filaggrin in allergic skin disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:280–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Oord RA, Sheikh A. Filaggrin gene defects and risk of developing allergic sensitisation and allergic disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2433. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson J, Northstone K, Lee SP, Liao H, Zhao Y, Pembrey M, et al. The burden of disease associated with filaggrin mutations: a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:872–7. e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thyssen JP, Kezic S. Causes of epidermal filaggrin reduction and their role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.014. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esparza-Gordillo J, Weidinger S, Folster-Holst R, Bauerfeind A, Ruschendorf F, Patone G, et al. A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:596–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun LD, Xiao FL, Li Y, Zhou WM, Tang HY, Tang XF, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Chinese Han population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:690–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirota T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Tsunoda T, Tomita K, Sakashita M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1222–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paternoster L, Standl M, Chen CM, Ramasamy A, Bonnelykke K, Duijts L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies three new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:187–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellinghaus D, Baurecht H, Esparza-Gordillo J, Rodriguez E, Matanovic A, Marenholz I, et al. High-density genotyping study identifies four new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:808–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon D, Ban HJ, Kim YJ, Kim EJ, Kim HC, Han BG, et al. Replication of genome-wide association studies on asthma and allergic diseases in Korean adult population. BMB Rep. 2012;45:305–10. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2012.45.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Luger TA, Stevens SR, Pride HB. Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1088–95. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000247298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genomes Project C. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consortium GT. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding J, Gudjonsson JE, Liang L, Stuart PE, Li Y, Chen W, et al. Gene expression in skin and lymphoblastoid cells: Refined statistical method reveals extensive overlap in cis-eQTL signals. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:779–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grundberg E, Small KS, Hedman AK, Nica AC, Buil A, Keildson S, et al. Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1084–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G, Yang E, Brinkmeyer-Langford CL, Cai JJ. Additive, epistatic, and environmental effects through the lens of expression variability QTL in a twin cohort. Genetics. 2014;196:413–25. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.157503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairfax BP, Makino S, Radhakrishnan J, Plant K, Leslie S, Dilthey A, et al. Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type-specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat Genet. 2012;44:502–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy A, Chu JH, Xu M, Carey VJ, Lazarus R, Liu A, et al. Mapping of numerous disease-associated expression polymorphisms in primary peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocytes. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4745–57. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairfax BP, Humburg P, Makino S, Naranbhai V, Wong D, Lau E, et al. Innate immune activity conditions the effect of regulatory variants upon monocyte gene expression. Science. 2014;343:1246949. doi: 10.1126/science.1246949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yatagai Y, Sakamoto T, Masuko H, Kaneko Y, Yamada H, Iijima H, et al. Genome-wide association study for levels of total serum IgE identifies HLA-C in a Japanese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira MA, Matheson MC, Duffy DL, Marks GB, Hui J, Le Souef P, et al. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13. 5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet. 2011;378:1006–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60874-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padyukov L, Seielstad M, Ong RT, Ding B, Ronnelid J, Seddighzadeh M, et al. A genome-wide association study suggests contrasting associations in ACPA-positive versus ACPA-negative rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:259–65. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulpiau P, van Roy F. Molecular evolution of the cadherin superfamily. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:349–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mortensen LJ, Kreiner-Moller E, Hakonarson H, Bonnelykke K, Bisgaard H. The PCDH1 gene and asthma in early childhood. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:792–800. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00021613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koning H, Postma DS, Brunekreef B, Duiverman EJ, Smit HA, Thijs C, et al. Protocadherin-1 polymorphisms are associated with eczema in two Dutch birth cohorts. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:270–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koppelman GH, Meyers DA, Howard TD, Zheng SL, Hawkins GA, Ampleford EJ, et al. Identification of PCDH1 as a novel susceptibility gene for bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:929–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1621OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toncheva AA, Suttner K, Michel S, Klopp N, Illig T, Balschun T, et al. Genetic variants in Protocadherin-1, bronchial hyper-responsiveness, and asthma subphenotypes in German children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:636–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2012.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaneko S, Ohira M, Nakamura Y, Isogai E, Nakagawara A, Kaneko M. Relationship of DDX1 and NAG gene amplification/overexpression to the prognosis of patients with MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:185–92. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0156-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maksimova N, Hara K, Nikolaeva I, Chun-Feng T, Usui T, Takagi M, et al. Neuroblastoma amplified sequence gene is associated with a novel short stature syndrome characterised by optic nerve atrophy and Pelger-Huet anomaly. J Med Genet. 2010;47:538–48. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.074815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics C, Wellcome Trust Case Control C. Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu G, Rybakin V, Brzostek J, Paster W, Acuto O, Gascoigne NR. Fine-tuning T cell receptor signaling to control T cell development. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chabod M, Pedros C, Lamouroux L, Colacios C, Bernard I, Lagrange D, et al. A spontaneous mutation of the rat Themis gene leads to impaired function of regulatory T cells linked to inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–81. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hinds DA, McMahon G, Kiefer AK, Do CB, Eriksson N, Evans DM, et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of self-reported allergy identifies shared and allergy-specific susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:907–11. doi: 10.1038/ng.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirota T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Tsunoda T, Tomita K, Doi S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for adult asthma in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:893–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reubsaet LL, Meerding J, Scholman R, Arets B, Prakken BJ, van Wijk F, et al. Allergen-specific Th2 responses in young children precede sensitization later in life. Allergy. 2014;69:406–10. doi: 10.1111/all.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsang WY, Wang L, Chen Z, Sanchez I, Dynlacht BD. SCAPER, a novel cyclin A-interacting protein that regulates cell cycle progression. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:621–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith EJ, Allantaz F, Bennett L, Zhang D, Gao X, Wood G, et al. Clinical, Molecular, and Genetic Characteristics of PAPA Syndrome: A Review. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:519–27. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weidinger S, Willis-Owen SA, Kamatani Y, Baurecht H, Morar N, Liang L, et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and psoriasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4841–56. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levin AM, Mathias RA, Huang L, Roth LA, Daley D, Myers RA, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for serum total IgE in diverse study populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1176–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramasamy A, Curjuric I, Coin LJ, Kumar A, McArdle WL, Imboden M, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of genetic variants associated with allergic rhinitis and grass sensitization and their interaction with birth order. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:996–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonnelykke K, Matheson MC, Pers TH, Granell R, Strachan DP, Alves AC, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies ten loci influencing allergic sensitization. Nat Genet. 2013;45:902–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weidinger S, Gieger C, Rodriguez E, Baurecht H, Mempel M, Klopp N, et al. Genome-wide scan on total serum IgE levels identifies FCER1A as novel susceptibility locus. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.