Abstract

Objective

To perform a retrospective radiographic evaluation on the fracture reduction and implant position in the femoral head among patients with pertrochanteric fractures who had been treated using a cephalomedullary nail in lateral decubitus; and to assess factors that might interfere with the quality of the fracture reduction and with the implant position in using this technique.

Methods

Nineteen patients with a diagnosis of pertrochanteric fractures of the femur who had been treated using cephalomedullary nails in lateral decubitus were evaluated. For outpatient radiographic evaluations, we used the anteroposterior view of the pelvis and lateral view of the side affected. We measured the cervicodiaphyseal angle, tip-apex distance (TAD), spatial position of the cephalic element in relation to the head, and the bispinal diameter. To make an anthropometric assessment, we used the body mass index. Two groups of patients were created: one in which all the criteria were normal (TAD ≤25 mm, cervicodiaphyseal angle between 130° and 135° and cephalic implant position in the femoral head in the central–central quadrant); and another group presenting alterations in some of the criteria for best prognosis.

Results

Female patients predominated (57.9%) and the mean age was 60 years. Seven patients presented a central–central cephalic implant position. One patient present a cervicodiaphyseal angle >135° and the maximum TAD was 32 mm; consequently, 12 patients presented some altered criteria (63.2%). None of the characteristics evaluated differed between the patients with all their criteria normal and those with some altered criteria, or showed any statistically significant association among them (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

The technique described here enabled good reduction and good positioning of the implant, independent of the anthropometric indices and type of fracture.

Keywords: Pertrochanteric, Cephalomedullary nail, Lateral decubitus, Femur fracture

Resumo

Objetivo

Fazer uma avaliação radiográfica retrospectiva da redução e posição do implante na cabeça femoral em pacientes com fraturas pertrocantéricas tratados com haste cefalomedular em decúbito lateral e fatores que possam interferir na qualidade da redução da fratura e posição do implante no uso dessa técnica.

Métodos

Foram avaliados retrospectivamente 19 pacientes com diagnóstico de fratura pertrocantérica do fêmur tratados com haste cefalomedular em decúbito lateral. Para avaliação radiográfica ambulatorial usamos as incidências anteroposterior da pelve e o perfil do lado afetado. Aferimos o ângulo cervicodiafisário, o TAD, a posição espacial do elemento cefáfilo em relação à cabeça e o diâmetro biespinhal. Para avaliação antropométrica usamos índice de massa corporal. Foram criados dois grupos de pacientes, um com todos os critérios normais (TAD < 25 mm, ângulo cervicodiafisário entre 130° e 135° e a posição do implante cefálico na cabeça femoral no quadrante central-central) e outro com alteração em algum dos critérios de melhor prognóstico.

Resultados

Houve predomínio do sexo feminino (57,9%), com idade média de 60 anos. Sete pacientes ficaram com a posição do implante cefálico na posição central-central, um apresentou ângulo cervicodiafisário > 135° e o TAD máximo foi de 32 mm. Consequentemente, 12 pacientes apresentaram algum dos critérios alterados (63,2%). Nenhuma das características avaliadas diferiu ou mostrou associação estatisticamente significativa entre pacientes com todos os critérios normais e algum critério alterado (p > 0.05).

Conclusão

A técnica descrita permite uma boa redução e um bom posicionamento do implante, independentemente dos índices antropométricos e do tipo de fratura.

Palavras-chave: Pertrocantérica, Hastes cefalomedulares, Decúbito lateral, Fratura de fêmur

Introduction

Pertrochanteric fractures are common in the elderly population because of osteoporosis. Their incidence has increased significantly because of greater life expectancy among the population, with the estimate that this may double over the next 25 years.1 Every year, one in every 1000 inhabitants of developed countries is affected by these fractures and it has been estimated that by 2050, the annual cost of treatment (currently US$ 8 billion) may have doubled. Thus, this is considered to be one of the world's most important public health problems.2

Today, there is a consensus that fractures in the pertrochanteric region of the femur should be fixed surgically, given that the aim of surgical treatment is to achieve stable reduction and fixation that provide patients with early active and passive mobilization.3, 4

Many authors have recommended treatment for unstable pertrochanteric fractures consisting of modern intramedullary implants because of their greater capacity for load absorption5 and their potential for application to all fracture patterns. Fixation techniques for these fractures consisting of cephalomedullary nails can be performed best on a traction table. However, in the absence of this, another form of decubitus becomes necessary, such as oblique lateral decubitus,6 for this treatment.

The aim of this study was to perform a retrospective radiographic evaluation on fracture reduction and implant positioning in the femoral head, in patients with pertrochanteric fractures that were treated using a cephalomedullary nail, with the patient in lateral decubitus; and to evaluate factors that might interfere with the quality of the fracture reduction and implant positioning when this technique is used.

Material and methods

Between June 2012 and November 2013, 29 patients with a diagnosis of pertrochanteric fractures of the femur were treated using a cephalomedullary nail at the municipal hospital of São Paulo (SP). Among these patients, 19 returned for a retrospective final assessment, eight could not be found and two died within the hospital environment during the immediate postoperative period due to complications from their injuries. Eleven of the reassessed patients (57.9%) were female and eight (42.1%) were male, with a mean age of 60 years (range: 18–87). Regarding the trauma mechanism, there were 13 cases of a fall to the ground, four cases of falls from motorcycles, one case of gunshot wounds and one case of a fall from a bicycle. Eleven of these patients presented fractures on the left side and eight on the right side.

We used the AO classification for pertrochanteric fractures (31--): A1 comprises simple two-part fractures, with good bone support in the medial cortex; A2 comprises multi-fragment fractures, with the medial cortex and dorsal cortex (lesser trochanter) broken at several levels, but with an intact lateral cortex; and A3 also presents a broken lateral cortex (inverted oblique fractures).7 Among the preoperative radiographs evaluated, one presented the 31A1 pattern, eleven 31A2 and seven 31A3. The minimum duration of the postoperative evaluation was six months.

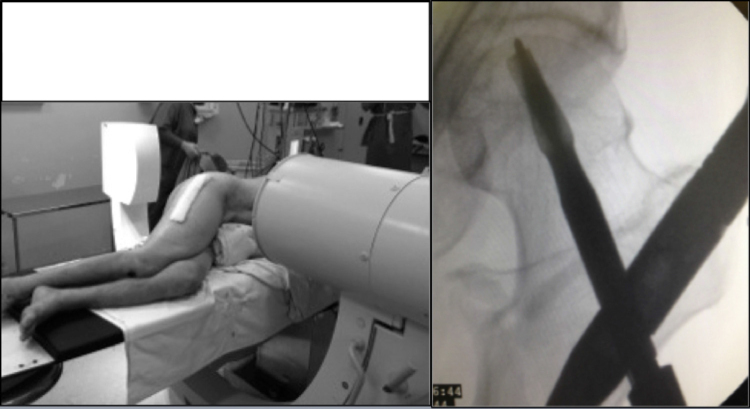

To perform the surgical procedure, the patient was put under general or spinal anesthesia while in lateral decubitus, with the aid of pads on the dorsum and abdomen on that side, using a radiotransparent table with an extender because of the short length. Radioscopic control was performed in anteroposterior (AP) view and lateral view, in order to ascertain the correct viewing of the entire femur and pelvis in the two planes. Following this, asepsis and antisepsis were performed on the side affected, from the iliac crest to the foot. The reduction was performed by means of manual traction, with some degree of rotation, adduction or abduction when necessary, with or without a mini-incision on the proximal lateral face of the thigh for fracture reduction. We used cephalomedullary nails (Gamma™ nail®, TFN®) and the standard technique8 for osteosynthesis of fractures. In the proximal fixation, it was sought to position the cephalic fixation element at the center of the head, 1 cm from the subchondral bone in normal bone and 0.5 cm in osteoporotic bone, in AP and lateral views. The lateral fixation was performed by means of a guide when a nail of standard size was used, or freehand in situations of long nails. At each stage, radioscopic control was performed both in AP and in lateral view. All the cases were operated by a third-year resident under supervision by the same senior attending physician (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Patient positioned in lateral decubitus – AP radioscopic view of the pelvis.

Fig. 2.

Patient positioned in lateral decubitus – lateral radioscopic view of the pelvis.

To perform outpatient radiographic assessments, we used the AP view of the pelvis with the patient in dorsal decubitus, with the rays incident on the median line of the public symphysis and the feet rotated internally at 15°–20°, in the standard technique; and the lateral view with the patient also positioned in dorsal decubitus, with the hip affected flexed at 45° and abducted at 20°, and with the ray centered vertically on the coxofemoral joint, in the standard technique.9 Through these views, the following were evaluated:

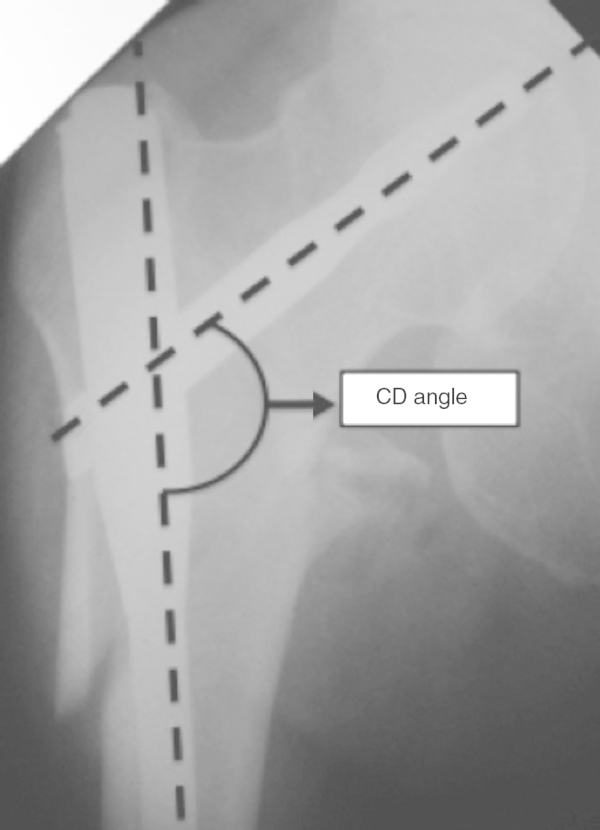

Cervicodiaphyseal angle: angle formed between two lines, one crossing the center of rotation of the femoral head and the center of the femoral neck, and the other along the long axis of the femur10 (Fig. 3).

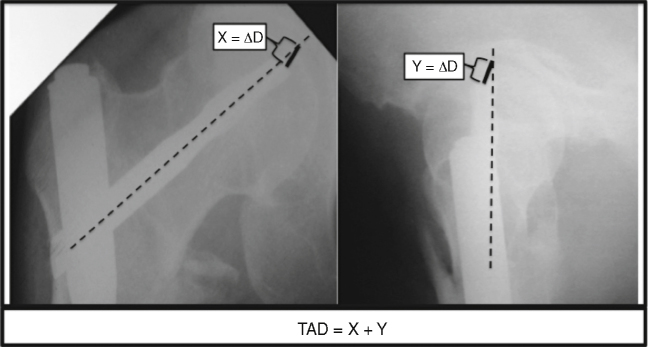

Tip-apex distance (TAD): defined in accordance with what was described by Baumgaertner et al.11 (Fig. 4).

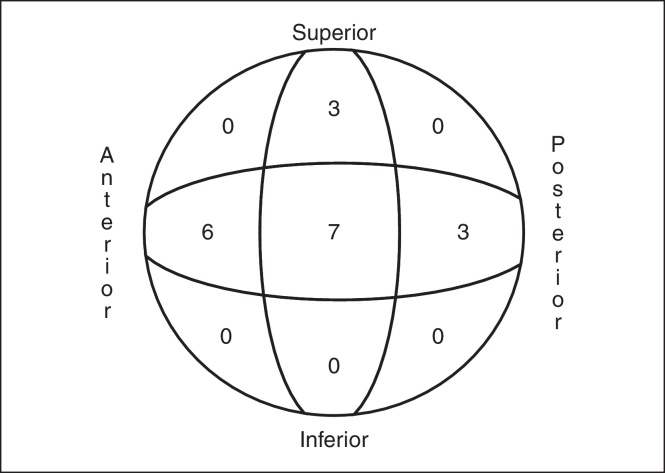

Spatial position of the cephalic element in relation to the head: the femoral head was divided into nine separate zones, in which the cephalic element might be located, as follows: upper, middle and lower thirds on AP radiographs and anterior, central and posterior thirds on lateral radiographs11 (Fig. 5).

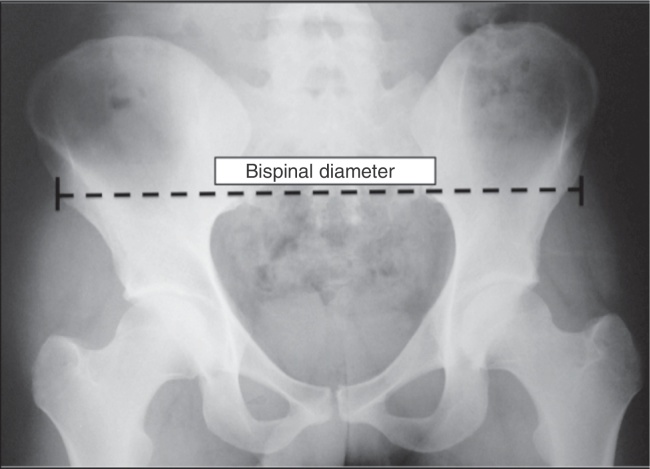

Bispinal diameter: this extended from the anterosuperior iliac spine on one side to that of the opposite side12 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Cervicodiaphyseal (CD) angle.

Fig. 4.

Tip-of-pin to apex-of-the-head distance (TAD).

Fig. 5.

Spatial position of the cephalic element in relation to the head.

Fig. 6.

Bispinal diameter.

To make anthropometric evaluations, we used the body mass index (BMI), which was calculated using weight and height measurements according to the following formula: BMI = weight (kg)/height2 (cm).13

The quantitative characteristics that were evaluated were described using summary measurements (mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum) and the qualitative characteristics were described using absolute and relative frequencies for all the patients in the study.14

Two groups of patients were created: one presenting normal values for all criteria (TAD ≤ 25 mm, cervicodiaphyseal angle between 130° and 135° and cephalic implant position in the femoral head located in the central–central quadrant); and the other with alterations to some of the criteria for better prognosis. The quantitative characteristics were described according to groups of patients and were compared between the groups using Student's t-test, while the qualitative characteristics were described according to the groups and were correlated using Fisher's exact test or the likelihood ratio test.14 The tests were performed using the significance level of 5%.

Results

Among the 19 patients evaluated, we found that the mean cervicodiaphyseal angle was 135°, with a range from 130° (84.2% of the patients evaluated) to 140° (5.3% of the patients evaluated). The mean values, maximum and minimum TAD, bispinal diameter, height, weight and BMI are described in Table 1. The distribution of the cephalic element is represented schematically as shown in Fig. 5. With regard to AO classification, one fracture (5.3%) was considered to be 31A1, eleven (57.9%) 31A2 and seven (34.8%) 31A3.

Table 1.

Description of the characteristics of all the patients evaluated.

| Variable | Description (n = 19) | Variable | Description (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Trauma mechanism | ||

| Female | 11 (57.9) | Fall to ground | 13 (68.4) |

| Male | 8 (42.1) | Other | 6 (31.6) |

| Age (years) | Width of pelvis (cm) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 60 (20.9) | Mean (SD) | 28 (3) |

| Median (min., max.) | 64 (18; 87) | Median (min., max.) | 28 (23; 34) |

| Weight (kg) | Position of cephalic implant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 68.2 (21.4) | Superior-central | 3 (15.8) |

| Median (min., max.) | 67.8 (40; 121) | Central-anterior | 6 (31.6) |

| Height (m) | Central–central | 7 (36.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.1) | Central-posterior | 3 (15.8) |

| Median (min., max.) | 1.6 (1.5; 1.9) | Cervicodiaphyseal angle | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 130° | 16 (84.2) | |

| Mean (SD) | 25.6 (6.8) | 135° | 2 (10.5) |

| Median (min., max.) | 22.4 (17.3; 40.4) | 140° | 1 (5.3) |

| Side | TAD (mm) | ||

| Right | 8 (42.1) | Mean (SD) | 22.5 (4) |

| Left | 11 (57.9) | Median (min., max.) | 22 (15; 32) |

| Classification | Criteria | ||

| A1 | 1 (5.3) | Normal | 7 (36.8) |

| A2 | 11 (57.9) | Some altered | 12 (36.2) |

| A3 | 7 (36.8) | ||

Table 1 shows that the majority of the patients evaluated were female (57.9%), with a mean age of 60 years (SD = 20.9). Seven patients had the cephalic implant in the central–central position; only one patient presented a cervicodiaphyseal angle greater than 135°; and the maximum TAD observed was 32 mm. Consequently, 12 patients presented some criteria that were altered (63.2%).

Table 2 shows that none of the characteristics evaluated differed or showed any statistically significant association between the patients presenting normal values for all criteria and those with some altered values (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Description of the characteristics evaluated according to alterations to the criteria and results from the statistical tests.

| Variable | Criteria |

Total (n = 19) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 7) | Some altered (n = 12) | |||

| Sex | >0.999 | |||

| Female | 4 (57.1) | 7 (58.3) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Male | 3 (42.9) | 5 (41.7) | 8 (42.1) | |

| Age (years) | 0.575a | |||

| Mean (SD) | 56.3 (21.2) | 62.1 (21.4) | 60 (20.9) | |

| Median (min., max.) | 50 (35; 85) | 64.5 (18; 87) | 64 (18; 87) | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.434a | |||

| Mean (SD) | 73.4 (20.1) | 65.1 (22.4) | 68.2 (21.4) | |

| Median (min., max.) | 70.4 (53; 101) | 67.3 (40; 121) | 67.8 (40; 121) | |

| Height (m) | 0.527a | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| Median (min., max.) | 1.6 (1.5; 1.8) | 1.6 (1.5; 1.9) | 1.6 (1.5; 1.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.456a | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.2 (8.1) | 24.7 (6.2) | 25.6 (6.8) | |

| Median (min., max.) | 22.4 (20.9; 40.4) | 22.7 (17.3; 37.3) | 22.4 (17.3; 40.4) | |

| Side | 0.377 | |||

| Right | 4 (57.1) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (42.1) | |

| Left | 3 (42.9) | 8 (66.7) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Classification | 0.598b | |||

| A1 | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.3) | |

| A2 | 4 (57.1) | 7 (58.3) | 11 (57.9) | |

| A3 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (33.3) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Trauma mechanism | 0.617 | |||

| Fall to ground | 4 (57.1) | 9 (75) | 13 (68.4) | |

| Other | 3 (42.9) | 3 (25) | 6 (31.6) | |

| Bispinal diameter | >0.999a | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28 (2.6) | 28 (3.4) | 28 (3) | |

| Median (min., max.) | 28 (23; 31) | 27 (23; 34) | 28 (23; 34) | |

Student's t-test.

Likelihood ratio test.

Discussion

Over recent years, the incidence of pertrochanteric fractures has increased as a result of increased life expectancy, consequent to improvement of the quality of life and also better healthcare. Many methods have been recommended for treating pertrochanteric fractures and there is unanimity in the literature regarding the recommendation that traction tables should be used for their treatment, or oblique lateral decubitus in the absence of such tables.6 However, because of the characteristics of our hospital service, we have not achieved good results through using this type of decubitus and we have therefore started to use the alternative of lateral decubitus.

Because this is a new technique, the reference standards that we used were the values encountered in cases of fractures in which the treatment was done on a traction table. Thus, we sought through reduction to reconstitute the normal cervicodiaphyseal angle of 130°–135°, so that the implant could be perfectly positioned and we would especially be able to avoid varus reductions.15, 16 In performing the proximal fixation, it was sought to position the cephalic fixation element at the center of the head, both in AP and in lateral view, at a distance of 1 cm from the subchondral bone in both views in normal bone and at 0.5 cm in osteoporotic bone. We followed the concept introduced by Baumgaertner et al.11 In the present study, we successfully obtained these parameters, given that we found a mean TAD of 22.5 mm (this was described for osteosynthesis using DHS and can be used for assessing whether the cephalomedullary nails have been correctly positioned)15 and a mean cervicodiaphyseal angle of 135°.

Since we used true lateral decubitus for obtaining lateral-view radioscopic images, we believe that greater pelvic width or obesity (measured indirectly from the bispinal diameter and BMI) would make it difficult to view and position the cephalic implant in lateral view. However, there was no statistical correlation between patients with greater BMI and bispinal diameters and those who presented TAD >25 mm and/or poor positioning of the cephalic fixation element, although we perceived that there was some intraoperative technical difficulty among the patients who were obese or whose pelvis was wider.

Among the nine possible locations for the proximal fixation element in the head, the location was distributed between four zones in our study: central–central (36.8%), central-anterior (31.6%), central-posterior (15.8%) and superior-central (15.8%). This shows that the areas at greatest risk of cutout (superior-anterior and inferior-posterior)11 were avoided (Fig. 5).

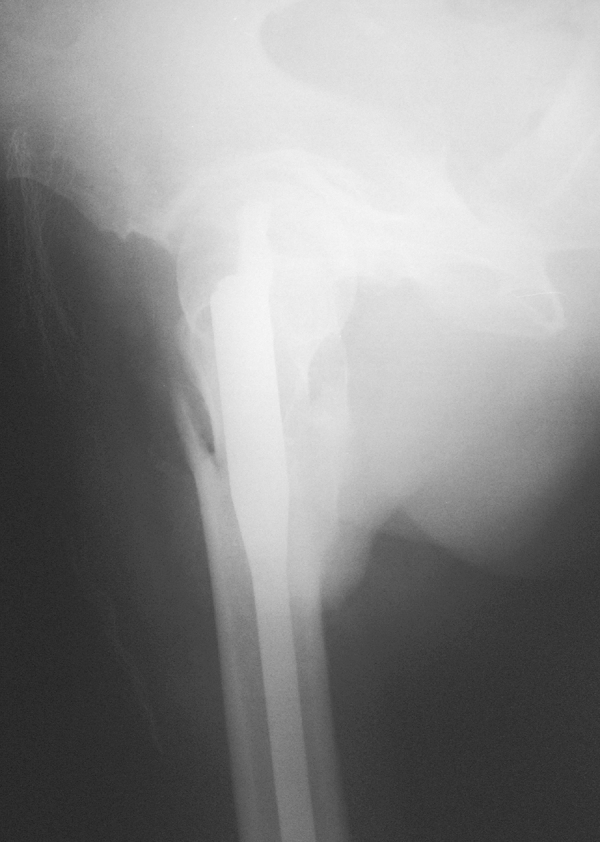

Pertrochanteric fractures have special importance at public health level, such that any useful technical evolution would have great human and economic value. Thus, lateral decubitus is a technique that can be chosen, which has been shown to enable good fracture reduction and good implant positioning in the femoral head, independent of anthropometric indices. It therefore becomes an option for treating these fractures in the absence of or impossibility of using a traction table or another type of decubitus (Fig. 7, Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

AP radiograph of the pelvis during the immediate postoperative period.

Fig. 8.

Lateral radiograph of the pelvis during the immediate postoperative period.

Conclusion

The technique described allows good fracture reduction and good implant positioning, independent of anthropometric indices and type of fracture.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Work performed in the Orthopedics and Traumatology Service, Hospital Municipal Dr. Fernando Mauro Pires da Rocha, Campo Limpo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Uliana C.S., Abagge M., Malafaia O., Kalil Filho F.A., Cunha L.A.M. Fraturas transtrocantéricas – Avaliação dos dados da admissão à alta hospitalar. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takano M.I., Moraes R.C.P., Almeida L.G.M.P., Queiroz R.D. Análise do emprego do parafuso antirrotacional nos dispositivos cefalomedulares nas fraturas do fêmur proximal. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucholz R.W., Court-Brown C.M., Heckman J.D., Tornetta P., III . 7th ed. Manole; Barueri, SP: 2013. Rockwood & Green fraturas em adultos. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pajarinen J., Lindahl J., Michelsson O., Savolainen V., Hirvensalo E. Pertrochanteric femoral fractures treated with a dynamic hip screw or a proximal femoral nail. A randomised study comparing post-operative rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridle S.H., Patel A.D., Bircher M., Calvert P.T. Fixation of intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. A randomised prospective comparison of the gamma nail and the dynamic hip screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(2):330–334. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirkin M.S., Behrens F., McCracken K., Aurori K., Aurori B., Schenk R. Femorl nailing without a fracture table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(332):119–125. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199611000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rüedi T.P. 2nd ed. Artmed; Porto Alegre: 2009. Princípios AO do tratamento de fraturas. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canale S.T. 12th ed. Mosby; St. Louis: 2013. Campbell's operative orthopaedics. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polesello G.C., Nakao T.S., Queiroz M.C., Daniachi D., Ricioli Junior W., Guimarães R.P. Proposta de padronização do estudo radiográfico do quadril e da pelve. Rev Bras Ortop. 2011;46(6):634–642. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30318-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pajarinen J., Lindahl J., Savolainen V., Michelsson O., Hirvensalo E. Femoral shaft medialisation and neck-shaft angle in unstable pertrochanteric femoral fractures. Int Orthop. 2004;28(6):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0590-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgaertner M.R., Curtin S.L., Lindskog D.M., Keggi J.M. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):1058–1064. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zugaib M. 2nd ed. Manole; Barueri, SP: 2012. Zugaib obstetrícia. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezende F.A.C., Rosado L.E.F.P.L., Ribeiro R.C.L., Vidigal F.C., Vasques A.C.J., Bonard I.S. Índice de massa corporal e circunferência abdominal: associação com fatores de risco cardiovascular. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006;87(6):728–734. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2006001900008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkwood B.R., Sterne J.A.C. 2nd ed. Blackwell Science; Malden, MA: 2006. Essential medical statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borger R.M., Leite F.A., Araújo R.P., Pereira T.F.N., Queiroz R.D. Avaliação prospectiva da evolução clínica, radiográfica e funcional do tratamento das fraturas trocantéricas instáveis do fêmur com haste cefalomedular. Rev Bras Ortop. 2011;46(4):380–389. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guimarães J.A., Guimarães A.C., Franco J.S. Avaliação do emprego da haste femoral curta na fratura trocantérica instável do fêmur. Rev Bras Ortop. 2008;43(9):406–417. [Google Scholar]