Abstract

A painful shoulder is a very common complaint among athletes, especially in the case of those in sports involving throwing. Partial lesions of the rotator cuff may be very painful and cause significant functional limitation to athletes’ sports practice. The incidence of partial lesions of the cuff is variable (13–37%). It is difficult to make the clinical and radiological diagnosis, and this condition should be borne in mind in the cases of all athletes who present symptoms of rotator cuff syndrome, including in patients who are diagnosed only with tendinopathy.

Objective

To evaluate the epidemiological behavior of partial lesions of the rotator cuff in both amateur and professional athletes in different types of sports.

Methods

We evaluated 720 medical files on athletes attended at the shoulder service of the Discipline of Sports Medicine at the Sports Traumatology Center, Federal University of São Paulo. The majority of them were men (65%). Among all the patients, 83 of them were diagnosed with partial lesions of the rotator cuff, by means of ultrasonography or magnetic resonance, or in some cases using both. We applied the binomial test to compare the proportions found.

Result

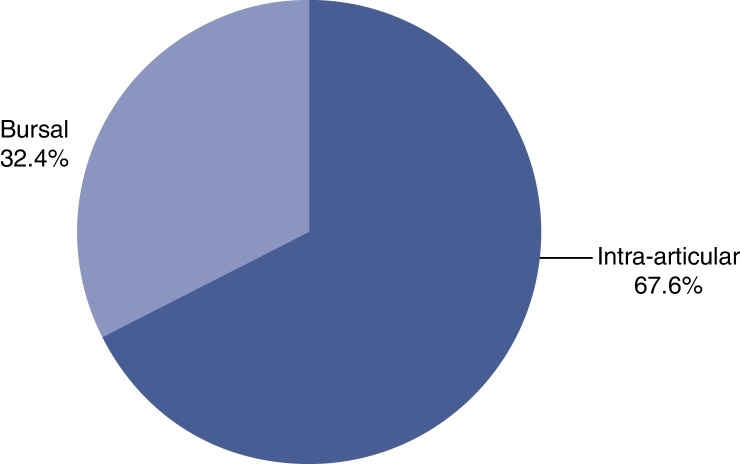

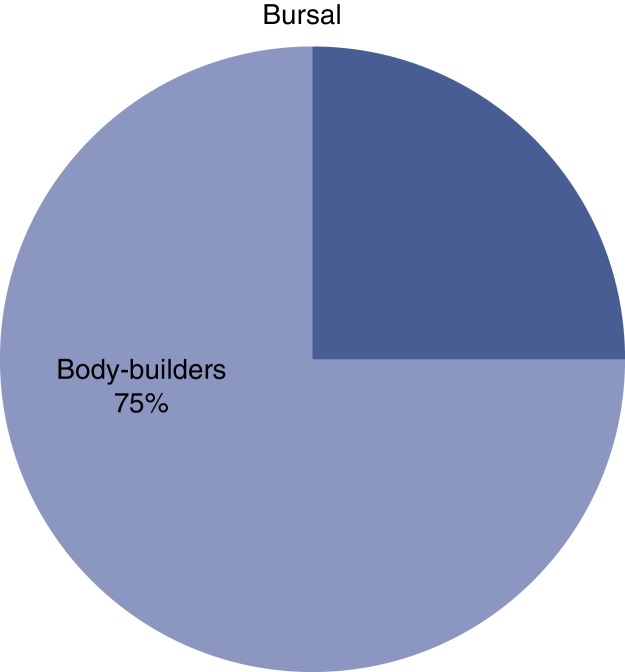

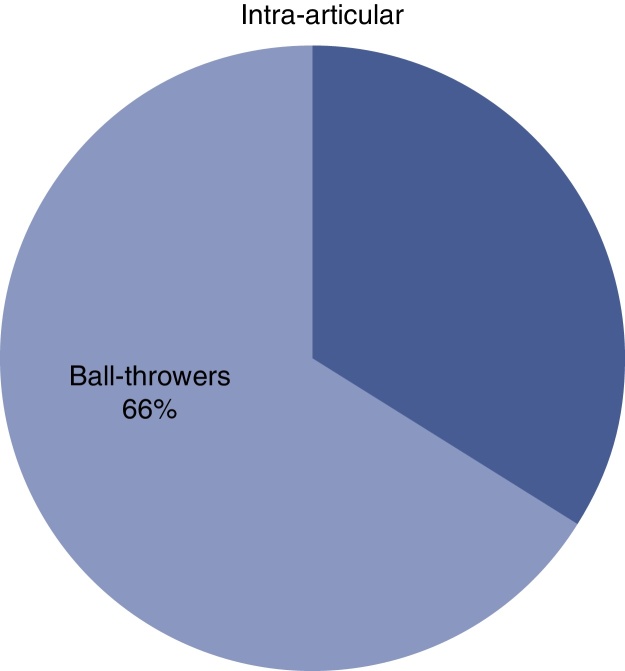

It was observed that intra-articular lesions predominated (67.6%) and that these occurred more frequently in athletes in sports involving throwing (66%). Bursal lesions occurred in 32.4% of the athletes, predominantly in those who did muscle building (75%).

Conclusion

Intra-articular lesions are more frequent than bursal lesions and they occur predominantly in athletes in sports involving throwing, while bursal lesions were more prevalent in athletes who did muscle building.

Keywords: Rotator cuff/injuries, Bursitis, Sports, Resistance training

Resumo

O ombro doloroso é uma queixa muito comum entre os atletas, especialmente no caso dos arremessadores. As lesões parciais do manguito rotador podem ser muito dolorosas e causar limitação funcional importante na pratica esportiva do atleta. A incidência das lesões parciais do manguito é variável (13% a 37%). O diagnóstico clínico e radiológico é difícil e deve ser considerado em todo atleta que apresente sintomatologia da síndrome do manguito rotador, inclusive nos pacientes diagnosticados apenas com tendinopatia.

Objetivo

Avaliar o comportamento epidemiológico das lesões parciais do manguito rotador nos atletas tanto amadores como profissionais de diferentes modalidades esportivas.

Métodos

Avaliamos 720 prontuários de atletas atendidos no serviço de ombro da disciplina de medicina esportiva no Centro de Traumatologia do Esporte da Universidade Federal de São Paulo, a maioria (65%) homens. Dentre todos, 83 pacientes foram diagnosticados com lesão parcial do manguito rotador por meio da ultrassonografia ou ressonância magnética e em alguns casos por ambas. Aplicamos o teste binomial para comparar as proporções encontradas.

Resultado

Verificou-se um predomínio das lesões intra-articulares (67,6%) e que essas ocorreram com maior frequência nos arremessadores (66%). Já com relação às lesões bursais, essas ocorreram em 32,4% dos atletas e predominam nos de musculação (75%).

Conclusão

As lesões intra-articulares são mais frequentes em relações às bursais e predominam nos atletas arremessadores, enquanto que as lesões bursais foram mais prevalentes nos atletas de musculação.

Palavras-chave: Bainha rotadora/lesões, Bursite, Esportes, Treinamento de resistência

Introduction

Painful shoulders are a very common complaint among athletes, especially in the case of those involved in ball-throwing sports. Partial tears of the rotator cuff may be very painful and cause significant functional limitation in athletes’ sports practice.1, 2

The clinical and radiological diagnosis of partial tears is difficult to make. Some studies have suggested that partial tears may be more painful that complete tears,3, 4, 5 although clinical examinations and the pain presented are poor indicators of the size of the lesion6 and also are no help in differentiating between partial and complete tears.7

Partial tears of the rotator cuff should be considered as a diagnosis for any patient who has been identified in preoperative examinations as presenting tendinopathy of the rotator cuff, or for any patient with complete tears, since there is evidence that a significant number of untreated partial tears evolve to larger or complete tears.8

The incidence of partial tears ranges from 13% to 37%.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Fukuda4 reported that partial tears occurred in 13% of their patients. Of these, 18% were bursal, 55% were within the tendon and 27% were inside the joint, on the tendon of the supraspinatus.

Rotator cuff injuries in athletes have been described in several studies in the literature recently.4, 6, 7, 12, 14, 15 However, the athletes most studied have been those involved in ball-throwing sports. The present study observed a pattern of partial tears of the rotator cuff both in these athletes and in those practicing muscle-building. We did not find any studies in the literature addressing these injuries in the latter type of sport.

Typically, rotator cuff injuries among athletes involved in ball-throwing sports occur in the articular portion of the tendon and at the junction between the tendons of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus.4, 6, 7, 12, 14, 15

There are basically two theories regarding the etiology of partial tears: the extrinsic and the intrinsic theory.

The extrinsic theory16, 17 describes abrasion between the rotator cuff and an abnormal acromion, in which the impact would result in a bursal lesion. For intra-articular lesions, another type of impact has been described: internal impact. In this, the supraspinatus impacts against the glenoid, especially when these athletes adopt a throwing position above head level.18, 19

On the other hand, the intrinsic theory is based on internal degeneration of the tendon. In histological studies, this degeneration is more prominent on the joint side of the tendon of the intact supraspinatus.20

Other factors have been described, such as trauma, repetitive movements, instability and an insidious start associated with degenerative age-related alterations.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Objective

To study the epidemiology of partial tears in athletes practicing different sports who were attended at the shoulder outpatient clinic for athletes at the Sports Traumatology Center (CETE) of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP).

Material and method

This study consisted of an initial evaluation of 720 medical files from the shoulder outpatient clinic for athletes of the Discipline of Sports Medicine of UNIFESP. Out of the total number of patients, 252 (35%) were women and 468 (65%) were men, with a mean age of 28.3 years. Among these patients, 34% were competitive athletes and 66% were recreational.

We divided the athletes into two groups: sports involving ball-throwing (volleyball, tennis and handball) and sports relating to muscle-building, such as body-building, base-training and gym training. There were 44 athletes in the first group and 39 in the second.

The inclusion criterion was that the patients should be athletes who were evaluated at our service and diagnosed with partial rotator cuff tears. Patients with other diagnoses, those who did not practice sports routinely, those presenting complete tears of the rotator cuff and those with associated glenohumeral pathological conditions such as arthrosis or infection were excluded.

Data were gathered using a form that sought clinical data such as pain and length of evolution of the condition, sex, type of sport and previous treatment. The provocative tests of Neer and Hawkins–Kennedy and the Jobe test were also conducted as part of the physical examination.

The diagnosis was confirmed either by ultrasonography or by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In some cases, the patient underwent both of these examinations.

All the patients signed a free and informed consent statement prior to participation in this study. The study had previously been submitted to our institution's ethics committee for research on human beings, for assessment and approval.

The data were evaluated and processed by means of the binomial test for comparison between two proportions. The Bioestat 5.0 software was used.27 We used the significance reference value of 5% (p < 0.05).

Results

Among the 720 athletes evaluated, 83 (11.5%) were diagnosed with partial tears of the rotator cuff. The diagnosis of rotator cuff injury was confirmed by means of ultrasonography in 74% of the cases and by means of MRI in 87% of the cases.

The sports-related injury mechanism was of traumatic origin in 35.3% of the athletes studied and was associated with repetitive movement in 64.7%.

We found an incidence of intra-articular lesions of 67.6%. Of these, 66% were in athletes involved in ball-throwing sports. On the other hand, the incidence of bursal lesions was 32.4% and 75% of these occurred in athletes who practiced muscle-building (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the partial rotator cuff tears among the athletes.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of bursal lesions.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of intra-articular lesions.

From applying the binomial test between the proportions found, we observed that there was a statistically significant relationship between the intra-articular and bursal lesions (p = 0.0001). The intra-articular lesions were more prevalent than the bursal lesions.

Among the intra-articular lesions, statistical significance was observed regarding the prevalence of the injuries found among the athletes involved in ball-throwing sports (p = 0.0007). Bursal lesions were prevalent among practitioners of muscle-building (p = 0.0004).

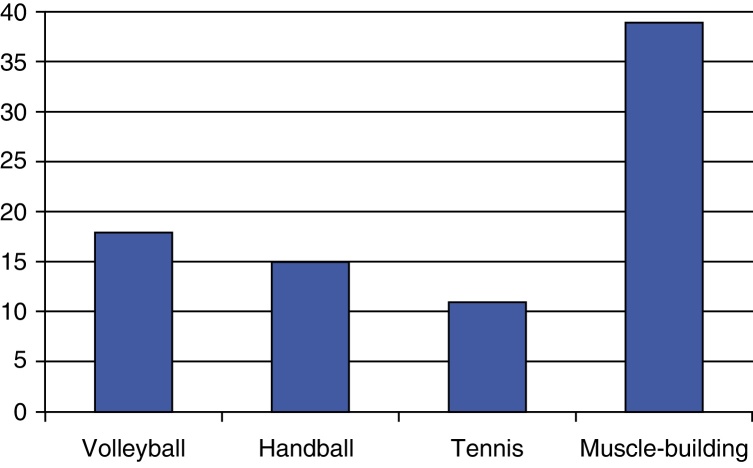

The sports most frequently affected were volleyball, handball, tennis and muscle-building, with 18, 15, 11 and 39 athletes affected, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution according to type of sport.

Thirty-four patients (40%) were symptomatic and refractory to conservative treatment. These patients underwent arthroscopy. The other patients achieved remission of the symptoms through conservative treatment alone.

Discussion

Partial tears of the rotator cuff in sports have been greatly studied. Both the Brazilian and the worldwide literature are vast in relation to these injuries in athletes involved in ball-throwing sports. Nevertheless, shoulder injuries in athletes are multifactorial and present some patterns that differ from those of the general population, which need to be noted. Moreover, we are unaware of any studies addressing this type of injury among muscle-builders.

We observed in this study that there was greater incidence of intra-articular lesions, of the order of approximately two to one, which is in line with current literature, which suggests that joint lesions are at least twice as frequent as bursal lesions1, 12, 21, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 and that the majority of partial tears involve the tendon of the suprasupinatus.22, 33, 34

This predominance of intra-articular lesions can perhaps be explained by the bursal and intra-articular characteristics of the tendon, which are different. The bursal layer is composed primarily of tendon bands with greater capacity for stretching and, therefore, greater resistance to tearing. On the other hand, the joint face is composed on a complex of tendons, capsules and ligaments. It has the characteristic of poor distensibility and greater predisposition to tearing.14

In the present study, 40% of the patients diagnosed with partial rotator cuff tears continued to show symptoms after conservative treatment. This proportion was much higher than what can be found in the literature, as represented by the systematic review by Reilly et al.,35 in which it was estimated that 5–10% of painful shoulders presented symptomatic partial rotator cuff tears. We considered that this important difference occurred because we were evaluating a population of athletes rather than the general population. Another factor might also have been the different age groups of the two studies: in the meta-analysis, the ages ranged from 43 to 54 years, while in our study the mean age was 28.3 years.

In some situations, the clinical and radiological diagnoses may be difficult to make, given that the clinical–radiological correlation may be low. The literature suggests that the pain may be more significant in partial tears3, 4, 5 and that no pattern of pain can be established for differentiating between partial tears and tearing that affects the entire thickness of the tendon.7 The gold standard for the diagnosis would really arthroscopy performed during the operation. However, according to more recent studies, arthro-MRI is indicated as the best radiological examination for this.36 It is superior to conventional MRI and ultrasonography and presents sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 96%. However, its interobserver accuracy for classifying tears both as partial or complete and in relation to the degree of partial tearing is poor, as observed by Kuhn et al.37 and Spencer et al.,38 respectively.

Within the world of sports, a series of associated factors has meant that these injuries have acquired some particular characteristics, such that diagnosing these injuries becomes more difficult. In some way, this makes them diverge from the epidemiological patterns of the general population. From this perspective, shoulder pain in athletes involved in ball-throwing sports has been correlated with a variety of conditions or dysfunctions, such as: subacromial impact,17, 38 anterior glenohumeral instability,39, 40 internal impact,17, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 contracture of the posterior capsule,43, 48, 49 medial rotation deficit,43, 48, 49 humeral retroversion,50 dysfunction of the trunk, scapula and shoulder musculature51 and biomechanical disorders.21

In individuals involved in ball-throwing sports and athletes who use their upper limbs in positions above head level, the internal impact seems to be the main cause of their shoulder pain.52 In the stage of preparing for the throw, there is abduction of the humerus at between 60° and 70°, at maximum external rotation. In this position, arthroscopic and MRI examinations have shown that the joint face of the posterior portion of the tendon of the supraspinatus and the superior portion of the tendon of the infraspinatus has an impact against the posterosuperior border of the glenoid and its labrum.7, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 This suggests that there is a biomechanical explanation for the predominance of intra-articular lesions.

Although the relationship established above is plausible and some studies point in this direction, other authors such as Walch,41 Jobe and Sidles46 and McFarland et al.44 have believed that this impact between the glenoid and the tendon might be physiological.

From this perspective, we observed different patterns in the two groups studied (athletes involved in throwing sports and muscle-builders). Intra-articular lesions predominated in the athletes involved in throwing sports (66%) and bursal lesions among the weight-lifters (75%).

The relationship between these injuries and ball-hitting sports like baseball, volleyball and handball, in which the injury mechanisms and patterns are very similar, if not the same, is well defined. A combination of the internal impact, lower vascularization of the joint portion, greater module of elasticity and concentration of eccentric forces on a surface that is less favorable to the curve of maximum tension52, 53 favors joint injuries in the rotator cuff. Extension of the lesion to layers that are more internal to the rotator cuff is notably recognized among athletes involved in throwing sports with internal impact.17, 54 However, we are unaware of any studies in the literature addressing the relationship of these injuries with individuals undertaking muscle-building in gyms, as observed in this study.

Also in relation to some characteristics of the injury, it is known that the inability of the tendon to become cured can be partially attributed to the poor vascular supply in the tendon of the supraspinatus.55, 56, 57 It has also been observed that the vascular supply is greater on the bursal side of the tendon.55, 58

On the other hand, in vivo studies have demonstrated that there is an increase in blood flow at the borders of complete tears.59 Moreover, there was hypervascularization in a small sample of partial tears.60 Histological studies have also suggested that the increases in vascularization are inversely proportional to the size of the lesion.61

Conclusion

In or study, the athletes were divided into two types: ball-throwers, encompassing volleyball, handball and tennis players; and practitioners of muscle-building, who could be doing this as a recreational or competitive activity, within body-building or base-training. We conclude that partial bursal lesions occur more frequently among individuals practicing muscle-building, while intra-articular lesions predominated among the athletes involved in ball-throwing sports.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Work developed in Hospital São Paulo, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Ellman H. Diagnosis and treatment of incomplete rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):64–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Lomas G., Kippe M.A., Brown G.D. In situ transtendon repair outperforms tear completion and repair for partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2008;17(5):722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.01.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss E.J., Salata M.J., Kercher J., Barker J.U., McGill K., Bach B.R., Jr. The arthroscopic management of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review of the literature arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda H. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a modern view on Codman's classic. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2000;9(2):163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gschwend N., Ivosevic-Radovanovic D., Patte D. Rotator cuff tear relationship between clinical and anatomopathological findings. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00463518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant L., Shnier R., Bryant C., Murrell G.A. A comparison of clinical estimation, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthroscopy in determining the size of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2002;11(3):219–224. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.121923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownlow H., Smith C., Corner T., Neen D., Pennington R. Pain and stiffness in partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(7):338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith C.D., Corner T., Morgan D., Drew S. Partial thickness rotator cuff tears: what do we know? Shoulder Elb. 2010;2(2):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löhr J.F., Uhthoff H.K. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of rotator cuff tears. Orthopade. 2007;36(9):788–795. doi: 10.1007/s00132-007-1146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depalma A. J. B. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1950. Surgery of the shoulder. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda H., Mikasa M., Yamanaka K. Incomplete thickness rotator cuff tears diagnosed by subacromial bursography. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(223):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne L.Z., Altchek D.W., Craig E.V., Warren R.F. Arthroscopic treatment of partial rotator cuff tears in young athletes. A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):299–305. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uhthoff H.K., Sano H. Pathology of failure of the rotator cuff tendon. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(1):31–41. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigliani L.U., Morrison D.S., April E.W. The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to the rotator cuff tears. Orthop Trans. 1986;10:228. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neer C.S., 2nd Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobe C.M. Superior glenoid impingement. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walch G., Boileau P., Noel E., Donell S.T. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: an arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1992;1(5):238–245. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sano H., Ishii H., Trudel G., Uhthoff H.K. Histologic evidence of degeneration at the insertion of 3 rotator cuff tendons: a comparative study with human cadaveric shoulders. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8(6):574–579. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsch A. Arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2007;16(2):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gartsman G.M., Milne J.C. Articular surface partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1995;4(6):409–415. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews J.R., Broussard T.S., Carson W.G. Arthroscopy of the shoulder in the management of partial tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1985;1(2):117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(85)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jobe F.W., Kvitne R.S., Giangarra C.E. Shoulder pain in the overhand or throwing athlete. The relationship of anterior instability and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Rev. 1989;18(9):963–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobe F.W., Pink M. Classification and treatment of shoulder dysfunction in the overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):427–432. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyons T.R., Savoie F.H., 3rd, Field L.D. Arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(2):219–223. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.8017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozaki J., Fujimoto S., Nakagawa Y., Masuhara K., Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1224–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordasco F.A., Backer M., Craig E.V., Klein D., Warren R.F. The partial-thickness rotator cuff tear: is acromioplasty without repair sufficient? Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(2):257–260. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayres M., Ayres M., Jr., Ayres DL, Santos AS . Sociedade Civil de Mamiraúa/CNPq; Belém, Brasília: 2007. Bioestat 5.0. Aplicações estatísticas nas áreas das ciências biológicas e médicas. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gartsman G.M. Arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1995;4(3):228–241. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itoi E., Tabata S. Incomplete rotator cuff tears. Results of operative treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(284):128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsewski J.M., Depew A.D. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression and rotator cuff debridement for stage II and stage III impingement. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber S.C. Arthroscopic debridement and acromioplasty versus mini-open repair in the treatment of significant partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):126–131. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.0150121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConville O.R., Iannotti J.P. Partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda H., Hamada K., Yamanaka K. Pathology and pathogenesis of bursal-side rotator cuff tears viewed from en-bloc histologic sections. Clin Orthop. 1990;(254):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reilly P., Macleod I., Macfarlane R., Windley J., Emery R.J. Dead men and radiologists don’t lie: a review of cadaveric and radiological studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(2):116–121. doi: 10.1308/003588406X94968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Jesus J.O., Parker L., Frangos A.J., Nazarian L.N. Accuracy of MRI, MR arthrography, and ultrasound in the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(6):1701–1707. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhn J.E., Dunn W.R., Ma B., Wright R.W., Jones G., Spencer E.E. Interobserver agreement in the classification of rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(3):437–441. doi: 10.1177/0363546506298108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spencer E., Jr., Dunn W., Wright R., Wolf B.R., Spindler K.P., McCarty E. Interobserver agreement in the classification of rotator cuff tears using magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:99–103. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neer C.S., 2nd Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop. 1983;173:70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montgomery W.H., 3rd, Jobe F.W. Functional outcomes in athletes after modified anterior capsulolabral reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(3):352–358. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson P.A., ElAttrache N.S., Jobe C.M. Rotator cuff and posterior–superior glenoid labrum injury associated with increased glenohumeral motion: a new site of impingement. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1995;4(5):384–390. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walch G. Rotator cuff disorders. 1996. Posterosuperior glenoid impingement; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jobe C.M. Current concepts: superior glenoid impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barber F.A., Morgan C.D., Burkhart S.S., Jobe C.M. Labrum bíceps cuff dysfunction in the throwing athlete. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(8):852–857. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.015085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McFarland E.G., Hsu Y.C., Neira C. Internal impingement of the shoulder: a clinical and arthroscopic analysis. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8(5):458–460. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jobe F.W., Tibone J.E., Perry J., Moynes D. A EMG analysis of the shoulder in throwing and pitching: a second report. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/036354658301100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jobe C.M., Sidles M. Evidence for a superior glenoid impingement upon the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1993;2(Suppl.):S19. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jobe C.M. Posterior superior glenoid impingement. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1995;11(5):530–536. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burkhart S.S., Morgan C.D. The peel-back mechanism: its role in producing and extending posterior type II SLAP lesions and its effect on SLAP repair rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):637–640. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan C.D. SLAP lesions in throwing athletes. Presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons meeting; Orlando, FL; 2000, February. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walch G., Levigne C. The cuff. Elsevier; Paris, France: 1997. Treatment of deep surface partial-thickness tears of the supraspinatous in patients under 30 years of age; pp. 243–244. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kibler B.W. Current concepts: the role of the scapular in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(2):325–337. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260022801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tibone J.E., Elrod B., Jobe F.W., Kerlan R.K., Carter V.S., Shields C.L., Jr. Surgical treatment of tears of the rotator cuff in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(6):887–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roye R., Grana W.A., Yates C.K. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: two-to-seven-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(3):301–306. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conway J.E. Arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears and SLAP lesions in professional baseball players. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32(3):443–456. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lohr J.F., Uhthoff H.K. The microvascular pattern of the supraspinatus tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rathbun J.B., Macnab I. The microvascular pattern of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52(3):540–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rothman R.H., Parke W.W. The vascular anatomy of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1965;41:176–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Codman E.A., Akerson I.B. The pathology associated with rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. Ann Surg. 1931;93(1):348–359. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193101000-00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy O., Relwani J., Zaman T., Even T., Venkateswaran B., Copeland S. Measurement of blood flow in the rotator cuff using laser Doppler flowmetry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(7):893–898. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.19918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swinontkowski M., Iannotti J.P., Hermann H., Esterhai J. Intraoperative assessment of rotator cuff vascularity using laser doppler flowmetry. In: Post M., Morrey B.F., Hawkins R.J., editors. Surgery of the shoulder. Mosby-Year Book; St Louis, MO: 1990. pp. 202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matthews T.J., Hand G.C., Rees J.L., Athanasou N.A., Carr A.J. Pathology of the torn rotator cuff tendon. Reduction in potential for repair as tear size increases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(4):489–495. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.16845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]