Abstract

Objectives

Our primary objective was to compare the utility of the Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCCI) and Elixhauser-van Walraven Comorbidity Index (EVCI) to predict mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

Setting

Observational study of 2 tertiary academic centres located in Boston, Massachusetts.

Participants

The study cohort consisted of 59 816 patients from admitted to 12 ICUs between January 2007 and December 2012.

Primary and secondary outcome

For the primary analysis, receiver operator characteristic curves were constructed for mortality at 30, 90, 180, and 365 days using the DCCI as well as EVCI, and the areas under the curve (AUCs) were compared. Subgroup analyses were performed within different types of ICUs. Logistic regression was used to add age, race and sex into the model to determine if there was any improvement in discrimination.

Results

At 30 days, the AUC for DCCI versus EVCI was 0.65 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.67) vs 0.66 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.66), p=0.02. Discrimination improved at 365 days for both indices (AUC for DCCI 0.72 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.72) vs AUC for EVCI 0.72 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.72), p=0.46). The DCCI and EVCI performed similarly across ICUs at all time points, with the exception of the neurosciences ICU, where the DCCI was superior to EVCI at all time points (1-year mortality: AUC 0.73 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.74) vs 0.68 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.70), p=0.005). The addition of basic demographic information did not change the results at any of the assessed time points.

Conclusions

The DCCI and EVCI were comparable at predicting mortality in critically ill patients. The predictive ability of both indices increased when assessing long-term outcomes. Addition of demographic data to both indices did not affect the predictive utility of these indices. Further studies are needed to validate our findings and to determine the utility of these indices in clinical practice.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There have been few studies examining the utility of comorbidity indices as predictors of mortality in patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

This study uses a large multi-institution cohort of critically ill patients admitted to several different intensive care units.

The results may not be generalisable to other institutions where coding practices may differ.

There is a chance of misclassification of vital status; however, there is no reason to suspect that this was differential between the two indices studied.

Introduction

Utilisation of critical care resources has continued to escalate over the past several years, despite attempts to reduce healthcare expenditures.1 2 The availability of reliable outcome predictors of critically ill patients may help improve the value of care. Providing information on expected mortality may help patients and relatives make informed decisions about their goals of care. In addition, comorbidity indices have become an important tool for policymakers, administrators and researchers to predict population-based outcomes.3

In the general population, two of the most commonly used indices are the Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index4 (DCCI) and the Elixhauser-van Walraven Comorbidity Index5 (EVCI). Originally proposed by Charlson et al6 in 1987, and then modified in 1992, the DCCI assigns a score to various chronic medical conditions and uses the sum to predict long-term mortality. Similarly, the EVCI score is based on 30 acute and chronic comorbidities to predict in-hospital mortality.7 In 2009, the Elixhauser score was modified by van Walraven et al5 into a weighted point system for streamlined use.

In contrast to scoring modalities such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), the DCCI and EVCI can be calculated at the time of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and do not require the interpretation of laboratory and bedside clinical data. Thus, they can be easily derived from administrative databases and their use in the critical care literature has been increasing. Both the DCCI and EVCI have been widely used to predict survival in acute hospital settings.8–11 There have been several studies demonstrating the validity of these indices to predict in-hospital mortality in ICU patients.12–16 Recent evidence suggests that the EVCI may be modestly superior to the DCCI for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients.17–20 However to date, there are few to no studies comparing DCCI to EVCI for use in critically ill patients when examining long-term mortality across a variety of types of ICUs. Our primary objective was to evaluate and compare the DCCI to EVCI for predicting mortality at 30, 60, 180, 365 days. Our secondary objectives were to: (1) compare DCCI and EVCI across medical and surgical ICU settings; (2) determine if adding three readily available patient characteristics (age, race and sex) to the DCCI and EVCI would improve prediction of mortality; and (3) to calculate the number of patients who would be reclassified based on predetermined mortality risk levels depending on which index was used.

Methods

Setting

We performed an observational study of ICU patients from two teaching hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts—Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital. Massachusetts General Hospital is a 1052-bed hospital with burn, cardiac surgery, coronary, medical, neonatal, neuroscience, paediatric and surgical ICUs. Brigham and Women's Hospital is a 793-bed hospital with burn, cardiothoracic, coronary, medical, neonatal, neuroscience and surgical ICUs.

Data source and study population

We performed an electronic chart review of all admissions to the ICUs at the two study centres. We included patients 18 years and older, admitted to any adult ICU from 1 January 2007 to 3 December 2012. In-hospital mortality data were captured via the medical record and mortality after discharge was obtained using the Social Security Administration's Death Master File. We excluded foreign nationals since they did not have social security numbers, and therefore mortality could not be verified in the Social Security Administration's Death Master File. For patients with multiple admissions to the ICU over the study time period, only the first admission to the ICU during the study time period was included in the analysis. Patients under the age of 18 were excluded (n=1206), as were patients with coding errors that prevented the calculation of either index (n=162).

Data collection and processing

We abstracted demographic and pertinent clinical information on all patients who met inclusion/exclusion criteria using a system-wide (including both hospitals) longitudinal patient data registry. Specific elements included were: (1) age; (2) sex; (3) race; (4) ICU type; (5) International Classification of Disease Clinical Modification 9 (ICD-9) discharge diagnosis codes; (6) hospital admission and discharge dates; (7) ICU admission and discharge dates; and (8) date of death.

The EVCI and DCCI were calculated using ICD-9 codes based on published algorithms.21 Race and ethnicities were coded into Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, Asian and Unknown/Other based on self-reported data. Age was treated as a continuous variable, and a sensitivity analysis was performed to ensure that there was no difference in model discrimination when age was included as 10-year categories. Time to death was calculated from the ICU admission date.

Statistical analysis

For both the DCCI and EVCI, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to generate the areas under the curve (AUCs) for predicting 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365-day mortality following ICU admission. To test differences in the discriminative ability of the indices, the AUCs were compared using a previously described non-parametric approach.22 This analysis was repeated for each type of ICU. For the primary analysis, each index was compared with the other both as the sole predictor as well as with age, sex and race included in the model. These factors were selected since they are typically easily available in administrative databases.

Given that the implications of differences in AUCs can be difficult to interpret, we set to calculate how many patients would undergo reclassification of mortality risk depending on which index score was used. The probability of mortality for an individual patient was calculated using a logistic regression model with DCCI as the sole independent covariate. Patients were then placed into predefined categories of predicted risk of mortality (0–4.9%, 5–9.9%, 10–14.9% and ≥15%). The patients were then reclassified into a higher, equal or lower risk classification based on their EVCI score as calculated from a separate logistic regression. The net reclassification improvement was calculated to determine whether this reclassification was appropriate.23

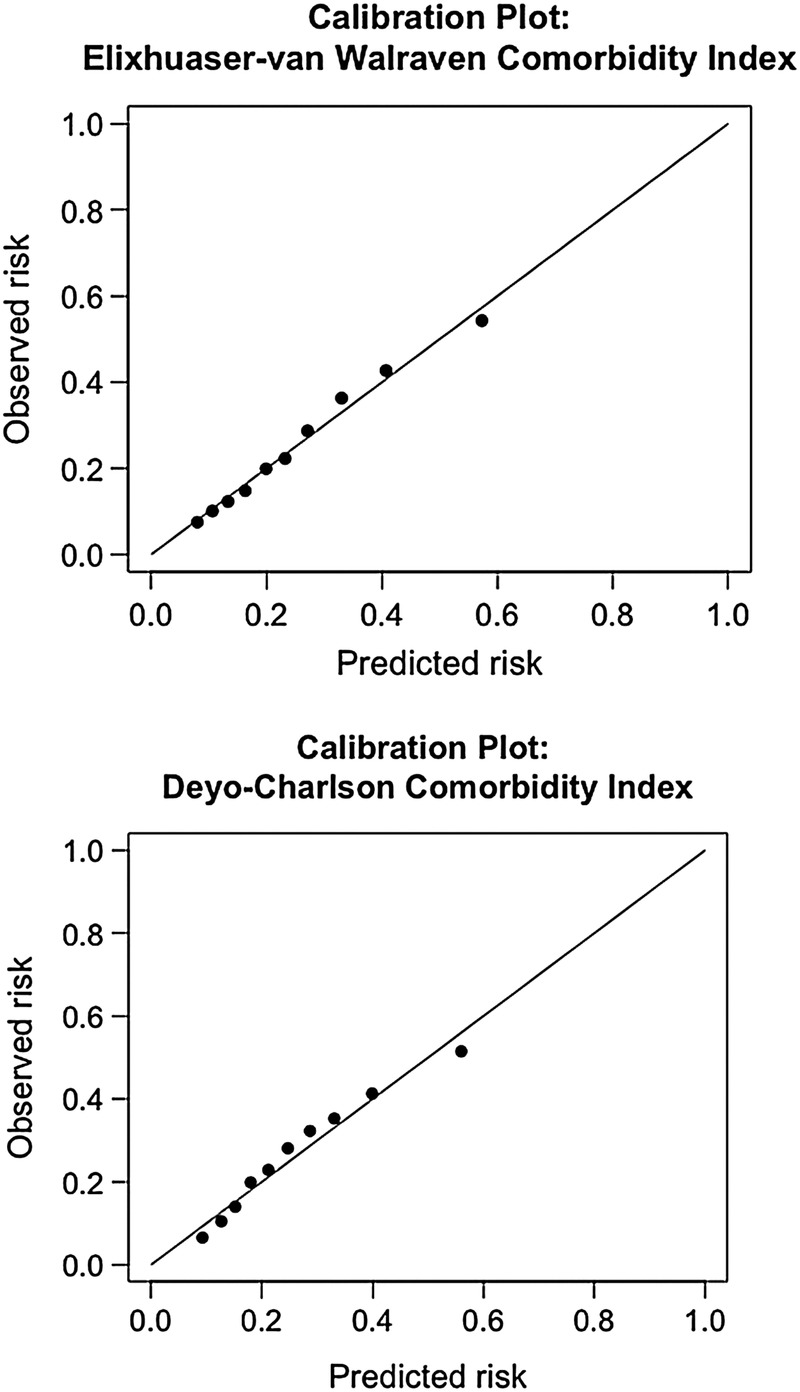

We also performed several additional analyses after the results of the above described analysis were obtained. To further understand the calibration of the models, calibration plots were created for each index with 1-year mortality as the outcome. We also constructed time-dependent ROC curves by modelling our data as a survival data set and assessed the AUC at the same time points as the primary analysis. Finally, we examined the discriminatory ability of the indices to predict prolonged length of stay in both the ICU and the hospital. These were defined as having a length of stay greater than the 75th centile, which was 5 days for the ICU and 16 days for the hospital.

The creation of the ROC curves and their analyses was performed in STATA V.12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The remainder of the analysis was performed in R V.3.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Specifically the reclassification analysis and the calibration plots were created using the PredictABEL package, and the time-dependent ROC curves were constructed using the timeROC package. All tests were performed with a two-tailed statistical level of significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Between January 2007 and December 2012, a total of 59 816 individual patients from 12 ICUs at two study hospitals met our study criteria (table 1). ICUs with the highest percentage of admissions included the cardiothoracic surgical ICU (23%), coronary care units, neurological/neurosurgical ICU (22%), medical ICU (19%) and surgical ICU (18%). Patients had a mean age of 64 (SD 16) and 81% of the population was Caucasian. The average DCCI score was 7 (SD 4) and the average EVCI was 16 (SD 12). Overall mortality at 30, 90, 180 and 365 days was 11%, 16%, 20% and 24%, respectively. The specific frequency of each comorbidity used to calculate the respective indices is presented in table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.3 (±16.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 48 274 (80.7) |

| Black | 3781 (6.3) |

| Hispanic | 2475 (4.1) |

| Asian | 1392 (2.3) |

| Unknown/other | 3894 (6.5) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 34 132 (57.1) |

| Female | 25 684 (42.9) |

| Admission ICU, n (%) | |

| Burn ICU | 3753 (6.3) |

| CCU | 7756 (12.9) |

| CTICU | 13 480 (22.5) |

| MICU | 11 419 (19.0) |

| NSICU | 12 864 (21.5) |

| SICU | 10 704 (17.9) |

| Mortality, n (%) | |

| 30 days | 6574 (11.0) |

| 90 days | 9651 (16.1) |

| 180 days | 11 960 (20.0) |

| 1 year | 14 551 (24.3) |

| Comorbidity score, mean (SD) | |

| Charlson | 7.22 (±3.81) |

| Elixhauser | 16.28 (±11.55) |

CCU, coronary care unit; CTICU, cardiothoracic ICU; ICU, intensive care unit; MICU, medical ICU; NSICU, neuroscience ICU; SICU, surgical ICU.

Table 2.

Frequency of individual constituents of each comorbidity index

| Deyo-Charlson comorbidities | Frequency (%) | Elixhauser-van Walraven comorbidites | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIDS | 371 (0.6) | HIV/AIDS | 369 (0.6) |

| Any malignancy | 23 249 (38.9) | Alcohol abuse | 3361 (5.6) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 20 926 (35.0) | Blood loss/anaemia | 1167 (2.0) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 16 097 (26.9) | Cardiac arrhythmias | 38 084 (63.7) |

| Congestive heart failure | 22 693 (37.9) | Chronic pulmonary disease | 15 877 (26.5) |

| Dementia | 1019 (1.7) | Coagulopathy | 13 187 (22.1) |

| Diabetes with complications | 3311 (5.5) | Congestive heart failure | 22 464 (37.6) |

| Diabetes without chronic complications | 17 063 (28.5) | Deficiency/anaemia | 13 336 (22.3) |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 4562 (7.6) | Depression | 8231 (13.8) |

| Metastatic solid tumour | 8627 (14.4) | Diabetes complicated | 4623 (7.7) |

| Mild liver disease | 2307 (3.9) | Diabetes uncomplicated | 16 821 (28.1) |

| Moderate/severe liver disease | 1996 (3.3) | Drug abuse | 2526 (4.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 18 123 (30.3) | Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 30 627 (51.2) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 4037 (6.8) | Hypertension complicated | 265 (0.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 9345 (15.6) | Hypertension uncomplicated | 33 857 (56.6) |

| Renal disease | 13 077 (21.9) | Hypothyroidism | 6468 (10.8) |

| Rheumatoid disease | 2230 (3.7) | Liver disease | 4631 (7.7) |

| Lymphoma | 3319 (5.6) | ||

| Metastatic cancer | 8559 (14.3) | ||

| Neurodegenerative disorders | 0 (0) | ||

| Obesity | 4285 (7.2) | ||

| Neurological disorders | 11 278 (18.9) | ||

| Paralysis | 4824 (8.1) | ||

| Peptic ulcer disease (excluding bleeding) | 1691 (2.8) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 12 963 (21.7) | ||

| Psychoses | 5942 (9.9) | ||

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 10 471 (17.5) | ||

| Renal failure | 12 605 (21.1) | ||

| Rheumatoid disorders | 2654 (4.4) | ||

| Solid tumour without metastasis | 23 476 (39.3) | ||

| Valvular heart disease | 14 033 (23.5) | ||

| Weight loss | 5857 (9.8) |

Predictors of mortality

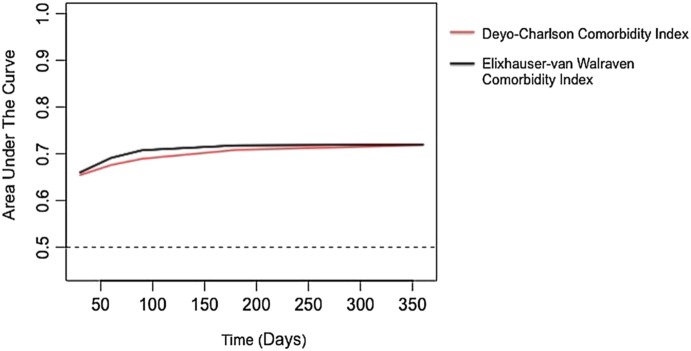

As a predictor of 30-day mortality, the AUC for the DCCI was 0.65 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.67) while AUC for the EVCI was 0.66 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.66), p=0.02. The AUCs increased as the time window for assessing mortality was lengthened. The AUC for 1-year mortality was 0.72 for both indices (AUC for DCCI 0.72 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.72) vs AUC for EVCI 0.72 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.72), p=0.46). Comparisons of AUCs for all study time points can be found in table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of area under receiver operator characteristic curves for the Charlson and Elixhauser Comorbidity Indices as predictors of mortality at various time points

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality | 0.65 (0.65 to 0.66) | 0.66 (0.65 to 0.67) | 0.02 |

| 90-day mortality | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.71) | <0.001 |

| 180-day mortality | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.71) | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.72) | <0.001 |

| 365-day morality | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.72) | 0.72 (0.72 to 0.72) | 0.46 |

Values represent area under the curve with 95% CIs in parentheses. p Values calculated by testing the difference between the areas under the curve using a t test.

Prediction by type of ICU

We compared the DDCI and EVCI within different subtypes of ICUs. Overall, the two indices predicted mortality similarly within each ICU type across different time periods. The exception to this was the neurosciences ICU where the DCCI was superior to the EVCI (1-year mortality AUC 0.73 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.74) vs 0.68 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.70), p=0.005). Table 4 lists the AUCs for 30-day and 365-day mortality across ICU types.

Table 4.

Comparison of area under receiver operator characteristic curves for the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices as predictors of mortality for different intensive care units

| 30-day mortality |

1-year mortality |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elixhauser | Charlson | p Value | Elixhauser | Charlson | p Value | |

| Burn ICU | 0.62 (0.58 to 0.65) | 0.63 (0.60 to 0.66) | 0.11 | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.75) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.75) | 0.57 |

| CCU | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.66) | 0.17 | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.73) | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.72) | 0.002 |

| CTICU | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.73) | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.70) | 0.001 | 0.75 (0.74 to 0.77) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.75) | 0.001 |

| MICU | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.65) | 0.03 | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.72) | 0.70 (0.69 to 0.71) | 0.005 |

| Neuro ICU | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.61) | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.67 to 0.70) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.74) | 0.005 |

| SICU | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.70) | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.001 | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.74) | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.73) | 0.050 |

Values represent area under the curve with 95% CIs in parentheses.

Addition of age, race, sex to the DCCI and EVCI

There was minimal improvement in discrimination when adding the comorbidity indices to basic demographic information (ie, age, race and sex) for both the DCCI and EVCI scores. The AUC for DCCI with demographic variables added was 0.67 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.67) for the prediction of 30-day mortality versus 0.65 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.66) for the index alone (p<0.001). The AUC for the EVCI score with demographics included was 0.73 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.74) for 1-year mortality compared with 0.72 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.72) for EVCI alone (p<0.001). Table 5 lists the various combinations and compares the AUCs to a prediction model with just demographic information. All of the indices and combinations with demographic information performed better than demographic variables alone with all p<0.001.

Table 5.

Areas under the curve for variation combinations of comorbidity indices and demographic data

| C-statistic | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality | ||

| Age, race, sex | 0.61 (0.60–0.62) | – |

| Charlson only | 0.65 (0.65–0.66) | Reference |

| Charlson, age, race, sex | 0.67 (0.66–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser only | 0.66 (0.65–0.67) | Reference |

| Elixhauser, age, race, sex | 0.69 (0.68–0.70) | <0.001 |

| 90-day mortality | ||

| Age, race, sex | 0.60 (0.59–0.60) | – |

| Charlson only | 0.69 (0.68–0.70) | Reference |

| Charlson, age, race, sex | 0.69 (0.69–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser only | 0.71 (0.70–0.71) | Reference |

| Elixhauser, age, race, sex | 0.73 (0.72–0.73) | <0.001 |

| 180-day mortality | ||

| Age, race, sex | 0.59 (0.59–0.60) | – |

| Charlson only | 0.71 (0.70–0.71) | Reference |

| Charlson, age, race, sex | 0.71 (0.71–0.72) | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser only | 0.72 (0.71–0.72) | Reference |

| Elixhauser, age, race, sex | 0.73 (0.73–0.74) | <0.001 |

| 365-day mortality | ||

| Age, race, sex | 0.59 (0.58–0.59) | – |

| Charlson only | 0.72 (0.71–0.72) | Reference |

| Charlson, age, race, sex | 0.72 (0.72–0.73) | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser only | 0.72 (0.72–0.72) | Reference |

| Elixhauser, age, race, sex | 0.73 (0.73–0.74) | <0.001 |

p Value for difference comparing the comorbidity index alone to a model with the respective comorbidity index plus age, race and sex included in the model.

Reclassification

The reclassification data highlight the differences between the DCCI and EVCI, showing the number of patients requiring reclassification when using a different index for predicting mortality (see table 6). When patients were divided into four categories of mortality likelihood, there were a total of 26 388 (44%) patients who required reclassification for their 30-day mortality risk. The net reclassification improvement for 30-day mortality risk was 7.5% (95% CI 6.8% to 9.1%) favouring the EVCI. This means that compared with individuals without the outcome, individuals with the outcome were 7.5% more likely to move up a risk category than down. When examining 1-year mortality risk, there were a total of 18 445 (31%) patients that required reclassification, with a net reclassification improvement of 4.4% (95% CI 3.5% to 5.2%).

Table 6.

Reclassification data based on predicted mortality

| Elixhauser predicted probability |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4.9% | 5–9.9% | 10–14.9% | ≥15% | Total | |

| 30-day mortality | |||||

| Charlson predicted probability | |||||

| 0–5% | 888 (15.3) | 1241 (4.7) | 117 (0.7) | 12 (0.1) | 2258 (3.8) |

| 5–10% | 4678 (80.4) | 19 899 (75.2) | 6301 (38.1) | 1515 (13.8) | 32 393 (54.2) |

| 10–15% | 159 (2.7) | 4348 (16.4) | 5955 (36.0) | 2772 (25.23) | 13 234 (22.1) |

| >15% | 93 (1.6) | 981 (3.7) | 4171 (25.2) | 6686 (60.9) | 11 931 (20.0) |

| Total | 5818 | 26 469 | 16 544 | 10 985 | 59 816 |

| 1-year mortality | |||||

| Charlson predicted probability | |||||

| 0–5% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5–10% | 33 (50.0) | 2332 (28.7) | 1499 (14.6) | 1322 (3.2) | 5186 (8.7) |

| 10–15% | 25 (37.9) | 3257 (40.1) | 3051 (29.7) | 4053 (9.8) | 10 386 (17.4) |

| >15% | 8 (12.1) | 2540 (31.3) | 5708 (55.6) | 35 988 (87.0) | 44 244 (74.0) |

| Total | 66 | 8129 | 10 258 | 41 363 | 59 816 |

Additional analyses

As further sensitivity analysis, model calibration of the indices was assessed through the plotting of calibration plots with the outcome of 1-year mortality. The plots are displayed in figure 1 and demonstrate adequate calibration. When analysing the data as a survival data set, the results of the calculated AUCs from the time-dependent ROC curves were similar to the primary analysis. The AUCs across time points are displayed in figure 2. When examining the ability of both indices to predict prolonged length of stay, the EVCI outperformed for the DCCI. For prolonged ICU stay, EVCI had an AUC of 0.64 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.64) versus the DCCI that had an AUC of 0.53 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.54) with a p value for difference of <0.001. When examining the ability to predict a hospital stay of greater than 16 days, EVCI had an AUC of 0.67 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.68) versus the DCCI which had an AUC of 0.57 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.57) with a p value for difference of <0.001.

Figure 1.

Calibration plots for Elixhauser-van Walraven Comorbidity Index and Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index for prediction of 1-year mortality after admission to the intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Calculation of areas under the curve from time-dependent receiver operator characteristic curves for one-year mortality.

Discussion

In our large cohort of ICU admissions, we found that the DCCI or EVCI were similar at predicting mortality at various time intervals and that the predictive ability of both indices increased when examining long-term outcomes. These results were consistent across various types of ICUs, with the exception of the neurosciences ICU where the DCCI was found to be superior. Consistent with a previous study,17 the indices performed better than demographic data alone. However, the addition of demographic data to both indices did not meaningfully affect the predictive utility of these indices.

Previous studies have shown that the EVCI, in general, appears to predict short-term and long-term mortality better than the DCCI for a variety of patients requiring acute hospitalisation.18–20

While the EVCI was statistically superior to the DCCI at predicting mortality at 30, 90 and 180 days, the difference was small and likely reached significance due to the large sample size of the study. When dividing the cohort into predicted risk categories, a large proportion of the population was reclassified into different categories depending on which index was used. However, the net reclassification index for 30-day mortality was only 7.5%. This suggests that while the EVCI may offer some advantage over the DCCI, the majority of this reclassification was not informative.

We did detect a difference between the two indices in the subgroup of patients admitted to the neurosciences ICU. While the reason for this observation is unclear, it may be due to the DCCI's heavy point allocation to metastatic solid tumours (6 points) and the additional points given to dementia (1 point) and cerebrovascular disease (1 point). The EVCI is less clear with regard to neurological diseases, allocating points to paralysis, ‘other neurological disorders’ and metastatic cancer.

Another interesting finding was that both indices improved mortality prediction over time. The AUC for the DCCI improved from 0.65 at 30 days to 0.72 at 365 days; and similarly, the AUC for EVCI improved from 0.66 at 30 days to 0.72 at 365 days. This improvement most likely is because as critically ill patients survive past their ICU stay, the major determinants of survival are related to their baseline comorbidities, age and new organ dysfunction as a result of their critical illness. Without prospective and organ dysfunction data, this is only a theory but two previous studies are congruent with our findings, where the researchers found that patients with higher organ dysfunction scores during their ICU stay had higher utilisation of healthcare resources and mortality up to 1 year, and possibly 5 years.24 25

Our study examined the real-world need of risk prediction with large administrative and claims databases for ICU patients. While physiology-based severity scores may have better predictive capabilities for short-term and long-term mortality, they are difficult to calculate without extensive resources. Additionally, these measures may not be available in large, historical cohorts of critically ill patients. In this study, we were not able to compare the DCCI and EVCI to commonly used physiology-based severity of illness scores. However, a previous study found that the combined DCCI with administrative variables performed similarly to physiology-based measures.14 Our results support this finding that a risk predictor based primarily on administrative data may be sufficient to serve as risk prediction tools in future studies, especially those examining long-term outcomes. Therefore, a lack of physiology-based severity scores does not preclude adequate risk adjustment of patients in studies of ICU patients using administrative databases. Given that both indices were similar in their discriminatory abilities, the DCCI may be more advantageous to use since it requires less data points to calculate it.

Our study has several limitations inherent to its design. First, calculation of these comorbidity indices is reliant on ICD-9 coding. This shortcoming was evident by the fact that none of the patients within our cohort had codes for a neurodegenerative disorder when calculating the EVCI. However, these coding discrepancies would likely be present when applying these metrics for non-research purposes, and thus the findings are representative of the ‘real-world’ accuracy of these indices. There is a risk of misclassification when assessing vital status; however, we have no reason to suspect that this risk was differential for either measure. Our cohort consisted of patients at two large academic hospitals, and thus the results may not be generalisable to other settings where coding practices may differ.

Conclusion

Our study found that the DCCI and EVCI were similar at predicting mortality in patients admitted to the ICU. Both indices demonstrated an improvement in discrimination as the time window of interest was lengthened. Given the policy, research and administrative implications of interpreting population data, selecting an accurate, yet practical comorbidity index for risk prediction is crucial. While a physiology-based comorbidity index is preferred for mortality risk assessment in ICU patients, our study suggests that either the DCCI or EVCI may be appropriate for predicting long-term mortality when physiology-based indices are not readily available. Further studies are needed to determine if the DCCI or EVCI can be used in place of physiology-based risk indices.

Footnotes

Contributors: KSL and JL contributed to the design and conception of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the work. KZ contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the work. SAQ, TK and RS contributed to the design and conception of the study, the interpretation of data, and drafting of the work. ENK contributed to the acquisition of data for the study and drafting of the work. All authors revised the work critically for important intellectual content.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SAQ has received within the past 2 years investigator-initiated research funding from the US National Institutes of Health (grants L30 GM102903, L30 TR001257 and T32 GM007592) and Harvard Medical School. TK has received within the past 2 years investigator-initiated research funding from the French National Research Agency and the US National Institutes of Health. Further, he has received honoraria from the BMJ and Cephalalgia for editorial services. ME has received within the past 2 years investigator-initiated research funding from Masimo, MERCK, the ResMed Foundation, and the Buzen’s Foundation. Further, he has received honoraria from the journal Anesthesiology for editorial services.

Ethics approval: Partners Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000–2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med 2010;38:65–71. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milbrandt EB, Kersten A, Rahim MT et al. Growth of intensive care unit resource use and its estimated cost in Medicare. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2504–10. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318183ef84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin SR, Wong YN, Uzzo RG et al. Why summary comorbidity measures such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Elixhauser Score Work. Med Care 2015;53:e65–72. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318297429c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–19. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A et al. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care 2009;47:626–33. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radovanovic D, Seifert B, Urban P et al. Validity of Charlson Comorbidity Index in patients hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome. Insights from the nationwide AMIS Plus registry 2002–2012. Heart 2014;100:288–94. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birim Ö, Kappetein AP, Bogers AJ. Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of long-term outcome after surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;28:759–62. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu H, Hill MD. Stroke: the Elixhauser Index for comorbidity adjustment of in-hospital case fatality. Neurology 2008;71: 283–7. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000318278.41347.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boorjian SA, Kim SP, Tollefson MK et al. Comparative performance of comorbidity indices for estimating perioperative and 5-year all cause mortality following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol 2013;190:55–60. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daubin C, Chevalier S, Séguin A et al. Predictors of mortality and short-term physical and cognitive dependence in critically ill persons 75 years and older: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:35 10.1186/1477-7525-9-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang CJ, Tam HP, Ko WJ et al. Predicting hospital mortality in adult patients with prolonged stay (>14 days) in surgical intensive care unit. Minerva Anestesiol 2013;79:843–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen S, Johansen MB, Christiansen CF et al. Comparison of Charlson comorbidity index with SAPS and APACHE scores for prediction of mortality following intensive care. Clin Epidemiol 2011;3:203–11. 10.2147/CLEP.S20247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho KM, Knuiman M, Finn J et al. Estimating long-term survival of critically ill patients: the PREDICT model. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e3226 10.1371/journal.pone.0003226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston JA, Wagner DP, Timmons S et al. Impact of different measures of comorbid disease on predicted mortality of intensive care unit patients. Med Care 2002;40:929–40. 10.1097/00005650-200210000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharabiani MTA, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care 2012;50:1109–18. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care 2004;42:355–60. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118861.56848.ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieffers JR, Baracos VE, Winget M et al. A comparison of Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity measures to predict colorectal cancer survival using administrative health data. Cancer 2011;117:1957–65. 10.1002/cncr.25653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin JH, Worni M, Castleberry AW et al. The application of comorbidity indices to predict early postoperative outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a nationwide comparative analysis of over 70,000 cases. Obes Surg 2013;23:638–49. 10.1007/s11695-012-0853-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45. 10.2307/2531595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72; discussion 207–12 10.1002/sim.2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranzani OT, Zampieri FG, Besen BAMP et al. One-year survival and resource use after critical illness: impact of organ failure and residual organ dysfunction in a cohort study in Brazil. Crit Care 2015;19:269 10.1186/s13054-015-0986-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lone NI, Seretny M, Wild SH et al. Surviving intensive care: a systematic review of healthcare resource use after hospital discharge*. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1832–43. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a409c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]