Abstract

Objectives

To examine interhospital variation in rates of induction of labour (IOL) to identify potential targets to reduce high rates of practice variation.

Design

Population-based record linkage cohort study.

Setting

New South Wales, Australia, 2010–2011.

Participants

All women with live births of ≥24 weeks gestation in 72 hospitals.

Primary outcome measure

Variation in hospital IOL rates adjusted for differences in case-mix, according to 10 mutually exclusive groups derived from the Robson caesarean section classification; groups were categorised by parity, plurality, fetal presentation, prior caesarean section and gestational age.

Results

The overall IOL rate was 26.7% (46 922 of 175 444 maternities were induced), ranging from 9.7% to 41.2% (IQR 21.8–29.8%) between hospitals. Nulliparous and multiparous women at 39–40 weeks gestation with a singleton cephalic birth were the greatest contributors to the overall IOL rate (23.5% and 20.2% of all IOL respectively), and had persisting high unexplained variation after adjustment for case-mix (adjusted hospital IOL rates ranging from 11.8% to 44.9% and 7.1% to 40.5%, respectively). In contrast, there was little variation in interhospital IOL rates among multiparous women with a singleton cephalic birth at ≥41 weeks gestation, women with singleton non-cephalic pregnancies and women with multifetal pregnancies.

Conclusions

7 of the 10 groups showed high or moderate unexplained variation in interhospital IOL rates, most pronounced for women at 39–40 weeks gestation with a singleton cephalic birth. Outcomes associated with divergent practice require determination, which may guide strategies to reduce practice variation.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, OBSTETRICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We applied a novel, totally inclusive yet mutually exclusive classification system for induction of labour (IOL)17 to understand the variation in hospital IOL rates for different clinical groups of pregnant women.

We used a large, recent, longitudinally linked, population-based surveillance data set of reliably collected labour and birth information.

Multilevel modelling was used to reduce the effect of random fluctuations and clustering in hospital rates of IOL.

However, population-based data do not allow exploration of variation in clinical thresholds for undertaking IOL; indication for labour induction; physician and patient attitudes; or cultural influences on decision-making.

Introduction

Variations in clinical practice will occur to some degree, as patient populations vary and healthcare should be individualised. However, for many medical interventions including in obstetrics,1 much of the clinical practice variation is unexplained (ie, not due to patient profiles, preferences or medical science).2 Unexplained clinical practice variation questions the appropriate usage of scarce resources,3 whether medical interventions are too few or too many, and whether healthcare provision is efficient or effective.4 5

Induction of labour (IOL) is a common obstetric intervention occurring in approximately a quarter of all births,6 7 with rates of IOL over time increasing in developing and developed countries.8 Large differences in overall IOL rates have been described between countries,9 provinces10 and hospitals.11 12 However, only one small study has previously reported overall interhospital IOL rates adjusting for patient characteristics12 and another report described hospital IOL rates for women by parity.13 Hospital populations differ in the proportions of women with factors (such as parity, prior caesarean section (CS), gestational age, number of fetuses and fetal presentation) that play a substantial role in clinical management of pregnant women; for example, most women who reach ≥41 weeks gestation are offered IOL, as perinatal outcomes are improved.14 Robson used all these factors to classify CSs,15 but the Robson groups are not directly applicable to IOL due to the heterogeneity of women who are ≥37 weeks gestation and have IOL.16 Therefore, we developed a classification or grouping system specifically for IOL,17 based on the same Robson classification factors. Analysis of variation in hospital IOL rates by these groups17 allows an assessment of whether variation in an overall pattern of hospital IOL is observed across all these clinical meaningful groups in which decision-making is expected to be similar. Hospitals may have high rates of IOL across all scenarios, suggesting inherent clinical attitudes towards offering IOL. Alternatively, the hospital IOL rate may be driven by the IOL rate of a particularly large group of women, for example, nulliparous women at term. In this case, targeted intervention strategies may be implemented for these particular groups of women.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe variation in hospital IOL rates using a novel classification system of 10 risk-based ‘induction groups’,17 while adjusting for case-mix and hospital factors.

Method

Study population

The study population included pregnancies resulting in a birth of a live born infant of ≥24 weeks gestation in hospital in New South Wales (NSW) between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2011. Multifetal pregnancies were treated as a single maternity. Hospitals were excluded if they did not have the capability to perform inductions (n=32, ie, excluding hospitals that only provided midwifery-led care), did not perform any inductions in the study period (n=29) or had fewer than 50 births/annum (n=24). Births were excluded if the birth record had missing data on the variables of interest (n=1330). Preterm births (births ≤36 weeks gestation) were also excluded if they occurred at hospitals which lacked the service capability to manage preterm infants (570 births at 27 hospitals, 5.1% of all preterm births), as although they manage preterm births in emergency situations, they were unlikely to perform planned IOL for preterm pregnancies and would not contribute to the understanding of variation in IOL rates. The population was then classified into 10 risk-based ‘induction groups’, categorised by parity, prior CS, gestational age, number of fetuses and fetal presentation (table 1).17

Table 1.

Rates of induction and measures of between-hospital variation, separately for 10 induction groups, NSW, 2010–2011

| Induction group17 | Births (n) | Relative size of group (%) | Inductions (n) | Percentage of group induced | Inductions as per cent of all inductions | Inductions as per cent of all births | Percentage of variance explained by case-mix | Percentage of hospitals different from average* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nulliparous, 37–38 weeks gestation, singleton cephalic fetus | 14 467 | 8.2 | 4823 | 33.3 | 10.3 | 2.7 | 11 | 29 |

| 2. Nulliparous, 39–40 weeks gestation, singleton cephalic fetus | 39 454 | 22.5 | 11 004 | 27.9 | 23.5 | 6.3 | 1 | 58 |

| 3. Nulliparous, ≥41 weeks gestation, singleton cephalic fetus | 14 124 | 8.1 | 8291 | 58.7 | 17.7 | 4.7 | −6 | 21 |

| 4. Multiparous, no previous CS, 37–38 weeks gestation, singleton cephalic fetus | 15 323 | 8.7 | 5075 | 33.1 | 10.8 | 2.9 | 30 | 28 |

| 5. Multiparous, no previous CS, 39–40 weeks gestation, singleton cephalic fetus | 40 527 | 23.1 | 9465 | 23.4 | 20.2 | 5.4 | 37 | 49 |

| 6. Multiparous, no previous CS, ≥41 weeks gestation, singleton cephalic fetus | 9538 | 5.4 | 4643 | 48.7 | 9.9 | 2.6 | 11 | 14 |

| 7. No previous CS, ≤36 weeks, singleton cephalic fetus | 6721 | 3.8 | 1396 | 20.8 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 20 | 17 |

| 8. Previous CS, singleton cephalic fetus | 26 174 | 14.9 | 1335 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 15 | 35 |

| 9. Singleton, non-cephalic fetus | 6524 | 3.7 | 307 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 43 | 3 |

| 10. Multifetal pregnancy | 2592 | 1.5 | 583 | 22.5 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 6 | 9 |

| Total | 175 444 | 100.0 | 46 922 | 100.0 | 26.7 |

*Proportion of hospitals for which the 95% CI of the adjusted hospital induction rate does not cross the crude state average.

Data source and study variables

Data were obtained from the NSW Perinatal Data Collection (PDC), a legislated population-based surveillance data set of all live births and stillbirths in NSW public and private hospitals and homebirths.18 Private hospitals provide obstetrician-led care, whereas public hospitals provide a mix of obstetrician-led, midwifery-led and mixed obstetric and midwifery-led care. At the time of the birth admission, the treating clinician or midwife completes a record of demographic, medical and obstetric information of the mother and the labour, delivery and condition of the baby, submits this record to the NSW Ministry of Health where the information in compiled into the PDC.19 The available information in the PDC on pregnancy, labour, delivery and maternal and infant characteristics has been validated and can be reliably used to evaluate maternity care.20–22 In the PDC, ‘onset of labour’ is collected by a single option check-box as ‘spontaneous’, ‘induced’ or ‘no labour’ (sensitivity 92.5%, positive predictive value 96.1%).20 Records from the PDC were linked longitudinally by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL)23 to create obstetric histories (previous births and CSs) for each woman in the study population. The primary outcome was the proportion of births at each hospital in which labour was induced within each induction group (table 1). In addition to the stratification factors, case-mix factors available for adjustment were infant size at birth (<10th centile: small for gestational age; 10–90th centile: appropriate for gestational age; >90th centile: large for gestational age), as well as maternal age, country of birth, smoking status, diabetes (pre-existing or gestational diabetes), hypertension (including chronic, gestational hypertension and preeclampsia) and type of care (public care in a public hospital, private care in a public hospital or private care in a private hospital).

Statistical analysis

Pregnancy and maternal characteristics were determined according to onset of labour (spontaneous labour, IOL or no labour in the case of prelabour CS). Multilevel logistic regression models were used to examine between-hospital variation in induction rates within each of the 10 induction groups, with hospitals as a random intercept. These models account for both differences in volume and potential clustering of similar women within hospitals. Hospital-specific induction rates (with 95% CIs) were obtained by converting the OR for each hospital into a relative risk and multiplying it by the state rate.24 For each group, the unadjusted and adjusted models of hospital induction rates were obtained. The proportion of variance among hospitals explained by adjusting for case-mix was calculated as the difference between the variance of the adjusted and unadjusted models, expressed as a proportion of the unadjusted model variance. To compare the extent of variation in hospital induction rates across groups, we calculated the percentage of hospitals in each group that were significantly different from the state average rate (ie, the proportion of hospitals for which the 95% CI of the adjusted induction rate did not cross the state average). We predefined cut-offs for variation as: high (>30%), medium (15–30%) or low (<15%) levels of variation. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (V.9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

In 2010 and 2011, there were 175 444 maternities at 72 hospitals. Of these, 46 922 (26.7%) followed IOL. The overall induction rate at NSW hospitals ranged from 9.7% to 41.2% (IQR 21.8–29.8%).

Pregnancy and maternal characteristics according to onset of labour are shown in table 2. When compared to women with spontaneous or no labour, women receiving an IOL were more likely to be nulliparous, born in Australia, have hypertension or diabetes or have a prolonged (>41 weeks gestation) pregnancy (table 2). Women who did not experience labour (ie, those who had prelabour CS) were older and more likely to receive private care than women being induced.

Table 2.

Maternal and pregnancy characteristics by onset of labour, NSW, 2010–2011

| Spontaneous | Induction | No labour | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=96 335 | n=46 922 | n=32 187 | n=175 444 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | <20 | 3821 (4.0) | 1641 (3.5) | 314 (1.0) | 5776 (3.3) |

| 20–34 | 73 171 (76.0) | 34 508 (73.5) | 19 973 (62.1) | 127 652 (72.8) | |

| ≥35 | 19 343 (20.1) | 10 773 (23.0) | 11 900 (37.0) | 42 016 (23.9) | |

| Born in Australia | 62 878 (65.3) | 32 951 (70.2) | 21 744 (67.6) | 117 573 (67.0) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 11 789 (12.2) | 5007 (10.7) | 2764 (8.6) | 19 560 (11.1) | |

| Diabetes | 4196 (4.4) | 4824 (10.3) | 2911 (9.0) | 11 931 (6.8) | |

| Hypertension | 1792 (1.9) | 5864 (12.5) | 2133 (6.6) | 9789 (5.6) | |

| Type of care | Private, private hospital | 17 901 (18.6) | 11 422 (24.3) | 11 703 (36.4) | 41 026 (23.4) |

| Private, public hospital | 6658 (6.9) | 4338 (9.3) | 3926 (12.2) | 14 922 (8.5) | |

| Public, public hospital | 71 776 (74.5) | 31 162 (66.4) | 16 558 (51.4) | 119 496 (68.1) | |

| Pregnancy Characteristics | |||||

| Nulliparity | 42 340 (44.0) | 25 242 (53.8) | 9022 (28.0) | 76 604 (43.7) | |

| Previous Caesarean (multiparous only) | 7535 (14.0) | 1359 (6.3) | 18 859 (81.4) | 27 753 (28.1) | |

| Singleton | 95 519 (99.2) | 46 339 (98.8) | 30 994 (96.3) | 172 852 (98.5) | |

| Cephalic presentation | 94 449 (98.0) | 46 603 (99.3) | 27 389 (85.1) | 168 441 (96.0) | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | ≤36 | 5609 (5.8) | 1610 (3.4) | 3349 (10.4) | 10 568 (6.0) |

| 37–40 | 79 787 (82.8) | 31 884 (68.0) | 27 943 (86.8) | 139 614 (79.6) | |

| ≥41 | 10 939 (11.4) | 13 428 (28.6) | 895 (2.8) | 25 262 (14.4) | |

| Infant size | SGA* (<10 centile) | 8759 (9.1) | 5259 (11.2) | 2834 (8.8) | 16 852 (9.6) |

| LGA† (>90 centile) | 8513 (8.8) | 4894 (10.4) | 4476 (13.9) | 17 883 (10.2) | |

*Small for gestational age.

†Large for gestational age.

Most inductions were among women at 39–40 weeks gestation (without a prior CS) with a singleton cephalic pregnancy (23.5% and 20.2% of all inductions for nulliparous and multiparous women, respectively; table 1). Within the induction groups, induction rates were highest for women without a prior CS at 41 or more weeks gestation with a singleton cephalic pregnancy (58.7% and 48.7% for nulliparous and multiparous women, respectively; table 1) and lowest for women with non-cephalic presentations (4.7%) or a history of having a previous CS (5.1%).

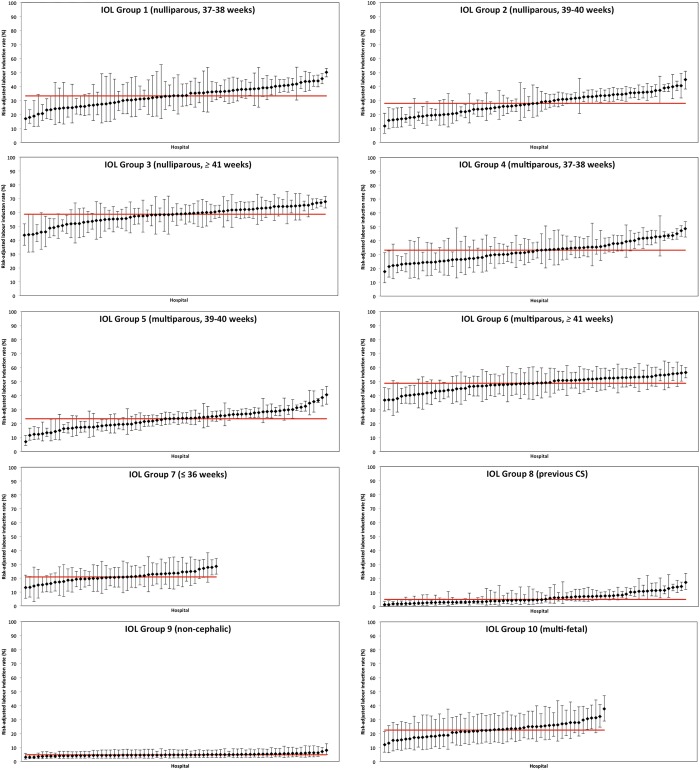

There was marked variation between-hospital IOL rates within the induction groups (figure 1). Adjusting for case-mix considerably reduced the variation between hospitals for induction for multiparous women at 37–38 (group 4, −30%) and 39–40 weeks (group 5, −37%) and single non-cephalic presentations (group 7, −43%) but only by a small proportion for nulliparous women at 37–38 (group 1, −11%) and 39–40 weeks (group 2, −1%) and multifetal pregnancies (group 10, −6%; table 1). In contrast, adjusting for case-mix slightly increased the between-hospital variance in inductions for nulliparous women at 41 or more weeks (group 3, +6%; table 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted hospital-specific induction rates, separately for each induction group, NSW, 2010–2011 (hospitals ordered from lowest to highest rate). *Red line represents the state average rate for each induction group.(CS, caesarean section; IOL, induction of labour).

After accounting for case-mix, high unexplained variation in hospital induction rates persisted for nulliparous and multiparous women at 39–40 weeks with a singleton cephalic pregnancy (groups 2 and 5) and for women with at least one previous CS (table 1). There was low variation in induction rates between hospitals for multiparous women at 41+ weeks with a singleton cephalic pregnancy (group 6, 14%), single non-cephalic presentations (group 9, 3%) and multifetal pregnancies (group 10, 9%): few hospitals had induction rates for these women who were significantly different from the overall average (figure 1).

Discussion

Principal findings

In 2010–2011, just over one-quarter of all births in our study population followed an IOL (26.7%), with considerable variation in hospital IOL rates across many groups of women having IOL, despite accounting for case-mix. Seven of the 10 groups had medium to high variation in hospital IOL rates (nulliparous and multiparous women at 37–38 and 39–40, nulliparous women ≥41, women with a prior CS and women ≤36 weeks gestation). The greatest between-hospital variation in IOL rates occurred in the two largest groups (group 2 and group 5: women with a singleton cephalic pregnancy at 39–40 weeks gestation, who accounted for 43.7% of all inductions). Only women with a singleton, non-cephalic presenting fetus, women with a multifetal pregnancy and multiparous women with a singleton, cephalic fetus at ≥41 weeks gestation had low between-hospital IOL rate variation, suggesting uniform clinical management across the hospitals for these groups of women. Efforts to standardise care for women having IOL should focus on groups of women with hospital IOL rates that have high variation, thereby potentially reducing practice variation and unnecessary intervention. Further research is required to understand the clinical decision-making and hospital factors that are driving this variation.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of this study were the use of large, contemporary, longitudinally linked, population-based data with reliably collected labour and birth information. This enabled the application of a totally inclusive yet mutually exclusive classification system for IOL17 allowing for similar pregnancies to be compared. Multilevel modelling was used to reduce the effect of random fluctuations in rates of IOL in low volume hospitals and allowed quantification of the contribution of case-mix factors to the variation in hospital IOL rates, while also accounting for similarities of births within hospitals. Hospitals included in the study were public and private hospitals (having either obstetrician care only or mixed obstetric-midwifery care) where IOL was offered, so they did not include any hospitals that were midwifery-only maternity units as these units would not offer IOL in NSW.25 26 However, population-level perinatal data lack detailed clinical information (such as severity of pregnancy and medical conditions), so they do not allow exploration of clinical variation in thresholds; indication for labour induction; physician and patient attitudes; or cultural influences on decision-making. Individual, pregnancy, clinical practice and hospital factors not accounted for in the model could contribute to increased variation between-hospital IOL rates. Information on individual practitioners is not available, and individual practitioners with either very high or very low IOL rates may influence an overall hospital rate of IOL. While this study focused on understanding the variation in hospital IOL rates for different clinical groups, differences in hospital IOL rates and pregnancy outcomes need to be explored to further guide practices to improve clinical care.

Interpretation

Practice variation has been related to medical uncertainty about the indications for and the efficacy of procedures.27 There is much evidence showing the importance of clinical opinion in influencing rates of procedures, which can also be altered by feedback and review.28 For example, in Wennberg et al's29 seminal work showing wide variations in rates of tonsillectomy in the state of Vermont, there was a rapid decline in rates of tonsillectomy after feedback of data to clinicians. The current study demonstrates considerable variation in hospital rates of IOL and is the first step in attempting to reduce unexplained variation.

The large variation in hospital IOL rates for women at 39–40 weeks gestation with a singleton cephalic pregnancy may indicate heterogeneity in thresholds for clinicians to recommend IOL as the patient has now reached ‘full term’. Often, the heterogeneity is related to differences in tolerance or clinical uncertainty of the risks and benefits of IOL at this gestational age compared to continuing the pregnancy.30 31 Such practice is, for example, indirectly endorsed by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Committee Opinion for ‘non-medically indicated early term delivery’,32 advising that non-medically indicated deliveries <39 weeks are not justified. This implies that once the parturient has reached 39 weeks, non-medically indicated full-term delivery may be justified. Alternatively, variation in hospital IOL rates at term may be driven by differences in clinical practice attributable to recent studies regarding the effects of IOL and a reduction in the risks of CS,33 or some other unmeasured clinician or patient factor. There is increasing interest in offering IOL at 39–40 weeks gestation, to prevent stillbirths beyond this gestational age (and potentially improve other perinatal outcomes), and there is a randomised trial currently recruiting patients.34

Among nulliparae, not only did hospital rates of IOL at full term have large variation, but also moderate variation was seen in hospital rates of IOL women at early term (29% of hospitals different from the average). A report from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists found large variation in adjusted hospital IOL rates for nulliparae ≥37 weeks gestation, with 45% of hospitals having IOL rates significantly different compared to the average.13 Our study found that only a small proportion of the variation in hospital IOL rates for nulliparae was explained by case-mix (11% and 1% for groups 1 and 2, respectively), suggesting that other factors affect IOL in this group. Further investigation of these factors affecting IOL for nulliparae is recommended as nulliparae at early and full-term make up one-third of all inductions; the proportion of nulliparae at early and full term being induced is increasing;35 and there appears to be a large unexplained variation in intrapartum CS rates following IOL for nulliparae.16 The importance of the first birth cannot be underestimated as it influences all subsequent births, and thus this large variation suggests that alternatives to a high IOL rate are achievable.

There was also large variation in hospital rates of IOL for women with a prior CS and a singleton cephalic fetus, with 35% of hospitals different from the average. However, only a small proportion of these women had an IOL (5.1% of the group), which may reflect concerns about adverse outcomes such as uterine rupture. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists statement suggests that IOL should be ‘undertaken with caution’.36 In contrast, other international guidelines (UK, USA and Canada) state that IOL is ‘appropriate’ for these women and that these countries have a higher proportion of women with a prior CS undergoing an IOL.37

There was low-to-moderate variation in hospital IOL rates for women ≥41 weeks gestation. There are many international guidelines recommending IOL for women ≥41 weeks gestation,38–40 to reduce perinatal mortality with no increase in the CS, based on evidence from a Cochrane review of 22 randomised controlled trials.14 For women in this gestational age group, there is clearer evidence regarding the management of this clinical scenario, which is reflected in less variation in hospital IOL rates.

The observed variation in hospital IOL rates is more extensive than the reported between-hospital variation in CS rates (ie, there are more hospitals where the rate of IOL is significantly different from the state average IOL rates compared to the number of hospitals where the rate of CS is significantly different).41 42 Different practice styles and clinical decision-making around obstetric intervention have been postulated in other studies as being related to overall hospital IOL11 and CS rate variation.41 42 Apart from hospital size and type of care, there may be other hospital factors such as staffing or resources that may also contribute to variation and warrant further investigation.

Variations in clinical practice are a form of a natural experiment, with outcomes and rates a result of the care provided by small groups of health professionals.29 43 It is problematic to specify the correct or target intervention rate such as a hospital IOL rate, particularly when the appropriate rate is likely to differ according to the ‘induction group’. Instead, the focus should be on achieving the best outcomes for mothers and babies with minimum intervention,1 reflecting not only improved clinical decision-making, but also efficient resource management. Hospitals that have lower rates of IOL, yet have the same outcomes for mothers and babies compared to hospitals with higher rates of IOL, provide opportunities to suggest changes in clinical practice for other institutions. Conversely, if hospitals with low rates of obstetric intervention such as IOL are associated with worse outcomes for mothers and babies, then interventions should increase to improve pregnancy outcomes. Further investigation into the pregnancy outcomes of the IOL groups that show large variation (such as those women at 39–40 weeks gestation) may be able to identify hospitals that have differing rates of IOL, yet the same pregnancy outcomes. In particular, hospitals with minimum intervention and yet the same outcomes may be studied to examine areas of clinical practice management that differ from other hospitals.

Conclusion

Considerable variation in hospital IOL rates persisted after accounting for case-mix. In particular, hospital IOL rates for women at 39–40 weeks gestation with a singleton cephalic birth showed high, unexplained variation, especially for nulliparous women. Further determination of outcomes associated with divergent IOL practice is required, which may guide strategies to standardise medical care and reduce practice variation and unnecessary interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the New South Wales Ministry of Health for access to the population health data and the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CheReL) for linkage of the data sets.

Footnotes

Contributors: CR and JM conceived the study. JT undertook data preparation and provided statistical analysis, with JP providing statistical oversight. TN, JT, JP, JF, CR and JM had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. TN, JT, JP, JF, CR and JM took part in interpretation of results, drafted the manuscript, approve and take responsibility for the final manuscript.

Funding: CR is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1021025) and JF by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT120100069). JT was employed by the NSW Ministry of Health on the NSW Biostatistical Officer Training Programme at the time this work was conducted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Reference No. 2012-12-430).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Glantz JC. Obstetric variation, intervention, and outcomes: doing more but accomplishing less. Birth 2012;39:286–90. 10.1111/birt.12002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corallo AN, Croxford R, Goodman DC et al. . A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy 2014;114:5–14. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulley AG. Improving productivity in the NHS. BMJ 2010;341:c3965 10.1136/bmj.c3965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wennberg JE. Time to tackle unwarranted variations in practice. BMJ 2011;342:d1513 10.1136/bmj.d1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ham C. Doctors must lead efforts to reduce waste and variation in practice. BMJ 2013;346:f3668 10.1136/bmj.f3668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Zeki R, Hilder L et al. . Australia's mothers and babies 2011. Perinatal statistics series no. 28. Cat. no. PER 59. Canberra: AIHW National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.HES. NHS maternity statistics 2011–12 summary report. The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel JP, Betran AP, Vindevoghel N et al. . Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e260–70. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70094-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EURO-PERISTAT Project with SCPE and EUROCAT. European Perinatal Health Report. The health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2010. May 2013.

- 10.Lutomski JE, Morrison JJ, Lydon-Rochelle MT. Regional variation in obstetrical intervention for hospital birth in the Republic of Ireland, 2005–2009. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:123 10.1186/1471-2393-12-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glantz JC. Rates of labor induction and primary cesarean delivery do not correlate with rates of adverse neonatal outcome in level I hospitals. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24:636–42. 10.3109/14767058.2010.514629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glantz JC, Guzick DS. Can differences in labor induction rates be explained by case mix? J Reprod Med 2004;49:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.RCOG. Patterns of maternity care in English NHS hospitals 2011/12. London, UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gülmezoglu AM, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6:CD004945 10.1002/14651858.CD004945.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robson MS. Classification of caesarean sections. Fetal Matern Med Rev 2001;12:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nippita T, Lee Y, Patterson J et al. . Variation in hospital caesarean section rates and obstetric outcomes among nulliparae at term: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 2015;122:702–11. 10.1111/1471-0528.13281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nippita TA, Khambalia AZ, Seeho SK et al. . Methods of classification for women undergoing induction of labour: a systematic review and novel classification system. BJOG. Published Online 26 Jun 2015. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demand and Performance Evaluation Branch, Centre for Epidemiology and Research. New South Wales perinatal data collection. NSW Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.New South Wales Ministry of Health. Perinatal data collection data dictionary. NSW Ministry of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts CL, Bell JC, Ford JB et al. . Monitoring the quality of maternity care: how well are labour and delivery events reported in population health data? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:144–52. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor L, Pym M, Bajuk B et al. . Validation study: NSW midwives data collection 1998. NSW Department of Health, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ampt AJ, Ford JB, Taylor LK et al. . Are pregnancy outcomes associated with risk factor reporting in routinely collected perinatal data? N S W Public Health Bull 2013;24:65–9. 10.1071/NB12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centre for Health Record Linkage. CHeReL—Quality Assurance 2011. http://www.cherel.org.au/quality-assurance (accessed 1 May 2014).

- 24.Mohammed MA, Manktelow BN, Hofer TP. Comparison of four methods for deriving hospital standardised mortality ratios from a single hierarchical logistic regression model. Stat Methods Med Res 2012. Published Online First. 10.1177/0962280212465165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. New South Wales mothers and babies 2012. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.New South Wales Health Department. Guide to role delineation of health services. Statewide services development branch. Sydney: NSW Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennberg JE. Forty years of unwarranted variation—and still counting. Health Policy 2014;114:1–2. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Jamtvedt G et al. . Growing literature, stagnant science? Systematic review, meta-regression and cumulative analysis of audit and feedback interventions in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1534–41. 10.1007/s11606-014-2913-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wennberg JE, Blowers L, Parker R et al. . Changes in tonsillectomy rates associated with feedback and review. Pediatrics 1977;59:821–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith G. Labour should be induced at term: FOR: the balance of risks versus benefits favours offering term induction to all women. BJOG 2015;122:982 10.1111/1471-0528.13399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacquemyn Y. Labour should be induced at term: AGAINST: no proof of benefit. BJOG 2015;122:982 10.1111/1471-0528.13400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ACOG committee opinion no. 561: Nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:911–15. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000428649.57622.a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood S, Cooper S, Ross S. Does induction of labour increase the risk of caesarean section? A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials in women with intact membranes. BJOG 2014;121:674–85. 10.1111/1471-0528.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy U. A randomized trial of induction versus expectant management (ARRIVE). 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01990612 (accessed 17 Jul 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Patterson JA, Roberts CL, Ford JB et al. . Trends and outcomes of induction of labour among nullipara at term. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;51:510–17. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. College Statement (C-Obs 38) Planned vaginal birth after caesarean section (trial of labour). Melbourne: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2015. https://www.ranzcog.edu.au/college-statements-guidelines.html#obstetrics (accessed 21 Aug 2015).

- 37.Hill JB, Ammons A, Chauhan SP. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: comparison of ACOG practice bulletin with other national guidelines. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012;55:969–77. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182708a60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO. WHO recommendations for induction of labour. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. Induction of labour. National Institute for health and clinical excellence guidelines. London: RCOG Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Practice bulletin no. 146: management of late-term and postterm pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124(2 Pt 1):390–6. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000452744.06088.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee YY, Roberts CL, Patterson JA et al. . Unexplained variation in hospital caesarean section rates. Med J Aust 2013;199:348–53. 10.5694/mja13.10279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennan DJ, Robson MS, Murphy M et al. . Comparative analysis of international cesarean delivery rates using 10-group classification identifies significant variation in spontaneous labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:308.e1–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SK, McMillan DD, Ohlsson A et al. . Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network: 1996–1997. Pediatrics 2000;106:1070–9. 10.1542/peds.106.5.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]