Abstract

Objective

External counterpulsation (ECP) is a non-invasive method used to augment cerebral blood flow of patients with ischaemic stroke via induced hypertension. We aimed to explore the correlation between the cerebral blood flow augmentation effects induced by ECP and clinical outcome after acute ischaemic stroke.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed our ECP registry of patients with ischaemic stroke who were enrolled within 7 days after stroke onset. Bilateral middle cerebral arteries of patients were monitored using transcranial Doppler (TCD). Flow velocity changes before, during and after ECP were, respectively, recorded for 3 min. The cerebral augmentation index (CAI) was the increase in percentage of the middle cerebral artery mean flow velocity during ECP compared with baseline. TCD data were analysed based on the side ipsilateral or contralateral to the infarct. The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) (good outcome: mRS 0∼2; poor outcome: mRS 3∼6) was evaluated 6 months after the index stroke.

Results

72 patients were included (mean age, 63.8±10.7 years; 87.5% males). At month 6 after stroke onset, univariate analysis showed that the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale at recruitment was significantly higher and ECP therapy duration was longer in the poor outcome group, while the ipsilateral CAI was significantly lower in the good outcome group than that in the poor outcome group (3.71±4.94 vs 7.73±7.66, p=0.044). Multivariate logistic regression showed that ipsilateral CAI was independently correlated with an unfavourable functional outcome after adjusting for confounding factors.

Conclusions

The higher degree of cerebral blood flow velocity augmentation on the side ipsilateral to the infarct induced by ECP is independently correlated with an unfavourable functional outcome after acute ischaemic stroke.

Keywords: STROKE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

For the first time, the degree of cerebral blood flow velocity augmentation on ipsilateral to the infarct side induced by external counterpulsation (ECP) is identified as an independent predictor of acute ischaemic stroke.

This is a retrospective study, and not all patients received 35 sessions of ECP treatment.

Our sample size is relatively small.

Introduction

External counterpulsation (ECP) is a non-invasive method to improve perfusion of vital organs. It operates by applying ECG-triggered diastolic pressure of ≈250 mm Hg to the lower extremities by means of three pairs of air-filled cuffs. The diastolic augmentation of the blood flow and the simultaneously decreasing systolic afterload therefore increases blood flow to the heart, brain and kidneys.1 2 Currently, it is an approved therapy for ischaemic heart disease with sustained long-term effects.3 4 ECP has been investigated for ischaemic stroke,5 and a recent review suggests that it is associated with a remarkable increase in the number of patients with ischaemic stroke with neurological improvement.6 Therefore, ECP is proposed as a potential therapy for patients with ischaemic stroke.

Our previous study showed that ECP is feasible for patients with ischaemic stroke with large artery disease by improving the clinical neurological deficit.7 ECP may improve cerebral perfusion and collateral blood supply in ischaemic stroke by augmentation of blood pressure (BP) and cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV).8 Measurement of the cerebral augmentation index (CAI) was proposed to evaluate augmentation effects induced by ECP.8 Besides, we found that duration of ECP therapy is an important predictor for good functional outcome for ECP-treated patients with ischaemic stroke, in addition to the well-known prognostic factors such as age and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) from our ECP registry, which only includes patients with ischaemic stroke.9 However, in that study, we did not analyse the cerebral augmentation effects induced by ECP on functional outcome. The cerebral augmentation effects of ECP on clinical outcome after acute ischaemic stroke are largely unknown. Thus, we conducted this pilot study further retrospectively analysing our ECP registry to examine whether the cerebral haemodynamic augmentation effects induced by ECP were correlated with long-term clinical outcome.

Participants and methods

Participant recruitment

Patients with acute ischaemic stroke were recruited to this study within 7 days of stroke onset. They were hospitalised in the Acute Stroke Unit, Prince Wales of Hospital, Hong Kong, from November 2010 to June 2013, because of ischaemic stroke that was diagnosed according to the definition of the WHO. All patients had a corresponding acute or subacute infarct for the index stroke from CT or MRI. Patients with good acoustic windows in transcranial Doppler (TCD) examination were recruited. Patients with relevant pontine and medullary or cerebellar infarcts were excluded, because our data analysis was based on the cerebral infarct side. Patients with evidence of cardioembolic stroke such as atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease, evidence of haemorrhage on brain CT, evidence of arteriovenous malformation, arteriovenous fistula, artery dissection or aneurysm, history of intracerebral haemorrhage, brain tumour or malignancy, sustained hypertension (systolic >180 mm Hg or diastolic >100 mm Hg), or severe symptomatic peripheral vascular disease were excluded as well. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment.

ECP TCD monitoring

ECP was performed using the Enhanced External Counterpulsation system, model number MC2 (Vamed Medical Instrument Company, Foshan, China). The treatment pressure of ECP was 150 mm Hg. TCD monitoring was performed using the ST3 TCD system (Spencer Technologies, Seattle, Washington, USA). The participants lay on the ECP treatment bed and their legs were wrapped with three pairs of air cuffs. Two 2 MHz probes were mounted on a head frame, which was fitted individually and worn on the head of participants. M1 segments of bilateral middle cerebral arteries (MCA) were insonated at the depth of the highest mean flow velocity between 50 and 60 mm. The standard duration of ECP therapy is 35 sessions (7 weeks), and we mainly focused on the investigation of haemodynamic effects of ECP on outcome in this study. The cerebrovascular reactivity responding to ECP intervention stabilised within 1 min. Therefore, in a practical way, we performed open-label ECP treatment for 3 min and monitored real-time changes of cerebral blood flow. Among patients who agreed to ECP as an adjunctive treatment of conventional medical therapy, TCD monitoring was performed at the first session of ECP treatment. Among patients who agreed to receive only medical treatment, we only performed 3 min open-label ECP treatment for TCD monitoring after recruitment. We recorded blood flow velocity of MCA before and during ECP, respectively, for 3 min. Immediately after ECP treatment stopped, we recorded another 3 min of MCA blood flow changes after ECP measurements. Continuous beat-to-beat BP was recorded using the Task Force Monitor system (CNSystems Medizintechnik AG, Graz, Austria) during the period of TCD monitoring. BP was measured in the supine position through finger cuffs which were applied on the index finger or the middle finger of left hand, and appropriate cuff size (small, medium or large) was chosen depending on the size of the hand.8 10

Clinical outcome

Assessment of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at 6 months after stroke was performed by a research assistant who was blind to TCD results at clinical visits of all patients.

Data analysis

Mean flow velocity of MCA was automatically recorded by the TCD system, which was the mean value of area under the envelope curve in a cardiac cycle. TCD data of patients with stroke were analysed based on the side ipsilateral or contralateral to the infarct. CAI was used to evaluate the cerebral augmentation effect of ECP, which was calculated by the increase in percentage of mean flow velocity during 3 min ECP treatment compared with baseline. We dichotomised the 6-month follow-up mRS into good outcome (mRS 0–2) and poor outcome (mRS 3–6). We compared the demographic differences (eg, age, gender and vascular risk factors) between two groups, as well as the medical history, medications the number of patients who received 35 sessions of ECP treatment and the cerebral haemodynamic parameters. Continuous data were analysed by independent-sample Student t tests when there was a normal distribution and by the Mann-Whitney test if there was a skewed distribution. Category data were analysed by the Pearson χ² test or Fisher's exact test. Logistic regression was used to calculate both crude and adjusted ORs of CAI on both sides and an unfavourable functional outcome after acute ischaemic stroke. ORs were adjusted for confounding factors, which were most significantly different (p<0.01) between the two groups in univariate analysis. All statistical analysis was performed with SPSS V.16.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Differences with p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Ninety-eight patients with acute ischaemic stroke with a good temporal window agreed to receive ECP TCD monitoring. Twenty-two patients were excluded because of pontine infarct. Four patients were lost to 6-month follow-up. Finally, there were 72 patients with ischaemic stroke (63 males; mean age 63.8±10.7 years; median NIHSS at recruitment 4) enrolled in this study. The median interval of stroke onset to examination was 4 days. Forty-two (58.3%) patients had a left-side cerebral infarct and the other 30 (41.7%) patients had a right-side cerebral infarct. Fifty-six (77.8%) patients had large artery disease and 14 (19.4%) patients had small vessel disease based on the criteria from the Trial of ORG 10 172 in the Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) study.11 In total, 48.6% of these 72 patients finished 35 sessions of ECP treatment and 51.4% only received medical treatment (table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of functional outcome groups

| Total cohort (72) | mRS 0–2 (53) | mRS 3–6 (19) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 63/9 | 46/7 | 17/2 | 0.560 |

| Age, years | 63.8±10.7 | 63±11.3 | 66±9 | 0.308 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 62 (86.1) | 46 (86.8) | 16 (86.1) | 0.524 |

| DM, n (%) | 37 (51.4) | 26 (49.1) | 11 (57.9) | 0.508 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 43 (59.7) | 32 (60.4) | 11 (57.9) | 0.850 |

| IHD, n (%) | 8 (11.1) | 4 (7.5) | 4 (21.1) | 0.121 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 22 (30.6) | 12 (22.6) | 10 (52.6) | 0.015 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 39 (54.2) | 32 (60.4) | 7 (36.8) | 0.077 |

| Drinking history, n (%) | 13 (18.1) | 11 (20.8) | 2 (10.5) | 0.267 |

| Stroke onset to recruitment (day) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–5) | 6 (3–7) | 0.128 |

| NIHSS at recruitment | 4 (4–8) | 4 (3–6) | 9 (6–12) | 0.001 |

| Systolic BP at recruitment (mm Hg) | 135.6±17.1 | 137±17.6 | 132.4±15.8 | 0.343 |

| Diastolic BP at recruitment (mm Hg) | 88.9±13.9 | 89.6±14.8 | 87.1±11.2 | 0.506 |

| HR (bpm) | 68.2±11.0 | 67.6±11.2 | 70±10.5 | 0.420 |

| ECP duration (h) | 0.002 | |||

| Finished 35 h ECP, n (%) | 35 (48.6) | 20 (37.7) | 15 (78.9) | |

| 3 Min open-label ECP, n (%) | 37 (51.4) | 33 (62.3) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Stroke subtype | 0.328 | |||

| LAD, n (%) | 56 (77.8) | 39 (73.6) | 17 (89.5) | |

| SVD, n (%) | 14 (19.4) | 12 (22.6) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Undetermined, n (%) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Infarct site | 0.094 | |||

| Left side, n (%) | 42 (58.3) | 34 (64.2) | 8 (42.1) | |

| Right side, n (%) | 30 (41.7) | 19 (35.8) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 63 (87.5) | 46 (86.8) | 17 (89.5) | 0.762 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 6 (8.3) | 5 (9.4) | 1 (5.3) | 0.573 |

| Statin, n (%) | 43 (59.7) | 30 (56.6) | 13 (68.4) | 0.368 |

*Represents p values for comparison between the two groups; Pearson χ² test, Fisher's exact test, independent-samples Student t test or Mann-Whitney test was used when appropriate.

Smoking history includes ex-smoker and current smoker (≥1 cigarette per day); drinking history includes ex-drinker and current drinker (≥1 drink per day). Continuous data were presented as the mean±SD if normally distributed or as the median and range if skew distributed.

BP, blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECP, external counterpulsation; HR, heart rate; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; LAD, large artery disease; mRS, modified-Rankin Scale scores; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SVD, small vessel disease.

Good outcome was found in 53 (73.6%) patients and bad outcome in 19 patients (26.4%) at the 6-month follow-up. Patients in the bad outcome group had a higher baseline NIHSS, more stroke and transient ischaemic attack history and a higher proportion of patients who received 35 sessions of ECP treatment. There was no significant difference on the use of medication between the two outcome groups (table 1). Mean BP at baseline, during ECP and mean BP increase during ECP from baseline were comparable in the two outcome groups (table 2). There were no significant differences in mean CBFV on both sides at baseline, during ECP and CAI on the contralateral side between the two groups. However, the CAI on the ipsilateral side of patients with a bad outcome (7.73±7.66) was markedly higher than that of patients with a good outcome (3.71±4.94, p<0.05, table 3).

Table 2.

Mean BP changes of subjects in functional outcome groups

| Total cohort (72) | mRS 0–2 (53) | mRS 3–6 (19) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean BP at baseline (mm Hg) | 99.26±17.05 | 99.28±17.02 | 99.21±17.61 | 0.987 |

| Mean BP during ECP (mm Hg) | 108.57±17.85 | 108.49±17.98 | 108.79±17.99 | 0.951 |

| Mean BP increase during ECP from baseline (%) | 9.78±8.39 | 9.64±8.47 | 10.17±8.38 | 0.817 |

*Represents p values for comparison between the two groups; independent-samples Student t test was used.

Continuous data were presented as the mean±SD.

BP, blood pressure; ECP, external counterpulsation; mRS, modified-Rankin Scale scores.

Table 3.

Blood flow velocity changes of subjects on both sides in functional outcome groups

| Total cohort (72) | mRS 0–2 (53) | mRS 3–6 (19) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean CBFV on ipsilateral side at baseline (cm/s) | 56.21±21.88 | 56.93±22.64 | 54.21±20.03 | 0.645 |

| Mean CBFV on ipsilateral side during ECP (cm/s) | 58.56±22.24 | 58.87±23.32 | 57.69±19.50 | 0.843 |

| CAI on ipsilateral side (%) | 4.77±5.99 | 3.71±4.94 | 7.73±7.66 | 0.044 |

| Mean CBFV on contralateral side at baseline (cm/s) | 56.16±21.31 | 54.92±19.89 | 59.64±25.12 | 0.465 |

| Mean CBFV on contralateral side during ECP (cm/s) | 58.70±22.73 | 57.11±21.10 | 63.15±26.87 | 0.324 |

| CAI on contralateral side (%) | 4.48±5.51 | 3.92±4.79 | 6.04±7.08 | 0.151 |

*Represents p values for comparison between the two groups; independent-samples Student t test was used.

Continuous data were presented as the mean±SD.

CAI, cerebral augmentation index; CBFV, cerebral blood flow velocity; ECP, external counterpulsation; mRS, modified-Rankin Scale scores.

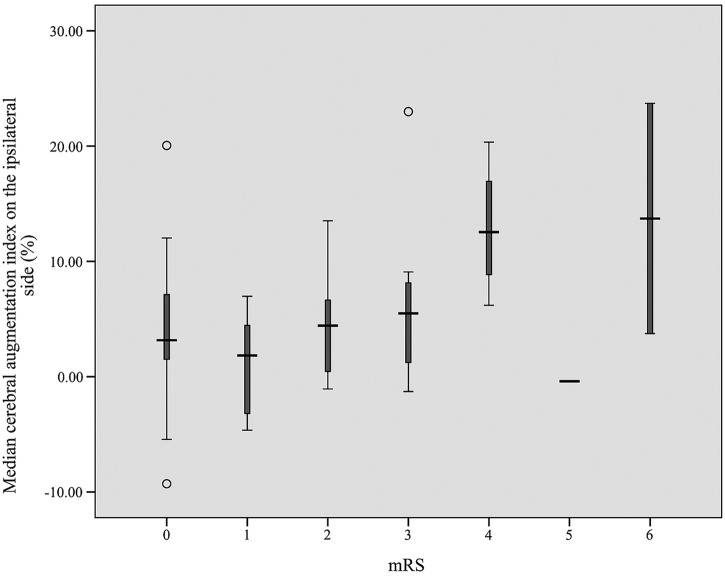

Crude ORs of CAI on the ipsilateral side (versus CAI on the contralateral side) and 6-month unfavourable functional outcome after acute ischaemic stroke were 1.118 (95% CI 1.018 to 1.229; p=0.019) and 1.011 (95% CI 0.989 to 1.034; p=0.323), respectively. After adjusting for confounding factors such as NIHSS at recruitment and ECP duration, respectively, which were the two variables most significantly different between the two groups in univariate analysis, the CAI on the ipsilateral side still showed significant association with unfavourable outcome, with ORs of 1.154 (95% CI 1.038 to 1.282; p=0.008) and 1.145 (95% CI 1.031 to 1.271; p=0.011), respectively (table 4). For 72 patients with ischaemic stroke, the distribution of median CAI on the ipsilateral side according to the 6-month mRS scores was shown in figure 1.

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted ORs of CAI on both sides and 6-month unfavorable functional outcome

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted for NIHSS at recruitment |

Adjusted for ECP duration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| CAI on ipsilateral side (%) | 1.118 (1.018 to 1.229) | 0.019 | 1.154 (1.038 to 1.282) | 0.008 | 1.145 (1.031 to 1.271) | 0.011 |

| CAI on contralateral side (%) | 1.011 (0.989 to 1.034) | 0.323 | 1.070 (0.965 to 1.187) | 0.197 | 1.065 (0.961 to 1.181) | 0.228 |

CAI, cerebral augmentation index; ECP, external counterpulsation; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Figure 1.

Distribution of median cerebral augmentation index on the ipsilateral side according to the 6-month modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores. The median and its box plot are shown. Thirty-five patients had mRS=0, 5 patients mRS=1, 13 patients mRS=2, 12 patients mRS=3 and 4 patients mRS=4, whereas only 1 patient had mRS=5 and 2 patients mRS=6.

Discussion

In the present study, we first investigated the correlation between the cerebral blood flow augmentation degree induced by ECP using TCD and clinical outcome after acute ischaemic stroke. We found that the CAI ipsilateral to the infarct side was independently significantly associated with clinical outcome after adjustment for well-known predictors such as baseline NIHSS and ECP duration, respectively. Patients with a higher CAI on the infarct side tended to have poorer functional outcome 6 months after stroke. Although there was no significant correlation between the CAI contralateral to the infarct side and 6-month functional outcome after stroke, patients with poor clinical outcome also showed a trend towards a higher CAI on the unaffected side.

To the best of our knowledge, ECP does not increase cerebral blood flow in the healthy brain, although BP is elevated during ECP.8 12 13 The intact cerebral autoregulation mechanism of healthy controls ensures cerebral blood flow stable under the fluctuation of BP during ECP. In our previous study, it was observed that ECP augments cerebral blood flow possibly via induced hypertension.8 In this study, the CAI of the total cohort was 4.77% on the ipsilateral side and 4.48% on the contralateral side, and mean BP increased 9.78% during ECP compared with baseline, which is consistent with our previous findings. Our recent study further demonstrated that the cerebral augmentation effect of ECP as measured by the CAI in patients with ischaemic stroke worked by the pathway of impaired cerebral autoregulation, not the well-established vasoreactivity to breath-holding; furthermore, the CAI of patients with stroke was related to mean BP change only on the ipsilateral side.14 Cerebral autoregulation is impaired after stroke.15 Therefore, we speculate that higher CAI ipsilateral to the infarct side might be related with worse impairment of autoregulation after acute ischaemic stroke. Reinhard et al16 found that impaired cerebral autoregulation on the affected side was associated with poor clinical outcome after a mean 4 months of acute ischaemic stroke onset. This may explain why the higher CAI ipsilateral to the infarct side was correlated with poorer clinical outcome after 6 months of acute ischaemic stroke onset. The reason why contralateral CAI was not associated with clinical outcome may relate to a complex network of collateral circulation improved by ECP.17 18

Currently, on the basis of empiric data from ECP studies in China,19 the standard duration of ECP treatment is generally several weeks (5 daily 1 h sessions each week for 7 weeks, for a total of 35 sessions). Patients with longer ECP treatment duration tend to have better functional outcome 3 months after stroke.9 In this study, patients with poor clinical outcome had a higher proportion of patients who received 35 sessions of ECP treatment in the univariate analysis. It may be attributed to the small sample size. However, after adjusting for the ECP duration, the ipsilateral CAI still showed independently significant association with clinical outcome. This indicated that ECP may be a new non-invasive tool to assess the cerebral haemodynamics after acute ischaemic stroke, and to assist us to better recognise those patients with unfavourable outcome for subsequent clinical intervention such as ECP directed at improving clinical neurological deficit.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is a retrospective study based on a registry. Second, the sample size is relatively small. This is why two multiple logistic regression models were used to analyse the correlations between the CAI on both cerebral sides with clinical outcomes to adjust for the confounding factors separately. Third, patients in the bad outcome group had a higher baseline NIHSS. However, multivariate logistic regression showed that ipsilateral CAI was still correlated with an unfavourable functional outcome independent of NIHSS at recruitment. Last, there is no follow-up treatment or intervention plan such as a standard 35 sessions of ECP treatment on those patients with poor outcome. However, we mainly focus on investigating effects of cerebral haemodynamic changes during ECP on clinical functional outcome. On the basis of the preliminary findings of this study, there is an ongoing prospective cohort study to validate the CAI evaluated by ECP as a predictor of clinical outcome in our centre, which will help us identify those patients at high risk for poor functional outcome to receive appropriate treatment following acute ischaemic stroke.

In summary, the cerebral augmentation effects of ECP as measured by CAI may be considered as a novel and non-invasive cerebral haemodynamic estimation index for predicting clinical outcomes after acute ischaemic stroke. Higher CAI ipsilateral to the infarct side is associated with unfavourable clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Focused Investment Scheme B) and the Lui Che Woo Institute of Innovative Medicine, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Footnotes

Contributors: LX collected and analysed the data and also drafted the manuscript. WL performed all experiments. JH helped guide how to perform TCD monitoring for all participants. XC revised the manuscript. TWHL and YOYS helped recruit patients. LKSW designed the study, analysed the data and gave revision opinions. All authors approved this version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the local medical ethics committee (Joint CUHK-NTEC Clinical Research Ethics Committee).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zheng ZS, Yu LQ, Cai SR et al. . New sequential external counterpulsation for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Artif Organs 1984;8:470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonetti PO, Holmes DR Jr, Lerman A et al. . Enhanced external counterpulsation for ischemic heart disease: what's behind the curtain? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1918–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michaels AD, Linnemeier G, Soran O et al. . Two-year outcomes after enhanced external counterpulsation for stable angina pectoris (from the international EECP patient registry [IEPR]). Am J Cardiol 2004;93:461–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora RR, Chou TM, Jain D et al. . The multicenter study of enhanced external counterpulsation (MUST-EECP): effect of EECP on exercise-induced myocardial ischemia and anginal episodes. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1833–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han JH, Wong KS. Is counterpulsation a potential therapy for ischemic stroke? Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;26:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin S, Liu M, Wu B et al. . External counterpulsation for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD009264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han JH, Leung TW, Lam WW et al. . Preliminary findings of external counterpulsation for ischemic stroke patient with large artery occlusive disease. Stroke 2008;39:1340–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin W, Xiong L, Han J et al. . External counterpulsation augments blood pressure and cerebral flow velocities in ischemic stroke patients with cerebral intracranial large artery occlusive disease. Stroke 2012;43:3007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin W, Han J, Chen X et al. . Predictors of good functional outcome in counterpulsation-treated recent ischaemic stroke patients. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin W, Xiong L, Han J et al. . Increasing pressure of external counterpulsation augments blood pressure but not cerebral blood flow velocity in ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci 2014;21:1148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ et al. . Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jungehuelsing GJ, Liman TG, Brunecker P et al. . Does external counterpulsation augment mean cerebral blood flow in the healthy brain? Effects of external counterpulsation on middle cerebral artery flow velocity and cerebrovascular regulatory response in healthy subjects. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;30:612–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner D, Marthol H, Brown CM et al. . Changes of cerebral blood flow velocities during enhanced external counterpulsation. Acta Neurol Scand 2003;107:405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin W, Xiong L, Han J et al. . Hemodynamic effect of external counterpulsation is a different measure of impaired cerebral autoregulation from vasoreactivity to breath-holding. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:326–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markus HS. Cerebral perfusion and stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinhard M, Rutsch S, Lambeck J et al. . Dynamic cerebral autoregulation associates with infarct size and outcome after ischemic stroke. Acta Neurol Scand 2012;125:156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gloekler S, Meier P, de Marchi SF et al. . Coronary collateral growth by external counterpulsation: a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2010;96:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buschmann EE, Utz W, Pagonas N et al. . Improvement of fractional flow reserve and collateral flow by treatment with external counterpulsation (Art.Net.-2 Trial). Eur J Clin Invest 2009; 39:866–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michaels AD, McCullough PA, Soran OZ et al. . Primer: practical approach to the selection of patients for and application of EECP. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2006;3:623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]