Abstract

Objective

The frontal assessment battery (FAB) is a quick and reliable method of screening to evaluate frontal lobe dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). However, previous studies were generally conducted on small samples representing different stages of disease and severity. We assessed the diagnostic accuracy of the FAB in detecting executive functions and its association with demographic and clinical features in ALS without dementia.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

A multidisciplinary tertiary centre for motor neuron disease.

Participants

We enrolled 95 consecutive patients with ALS diagnosed with El Escorial criteria in the period between January 2006 and December 2010.

Main outcome measures

We screened the patients with ALS using the FAB. An Executive Index (EI) was also calculated by averaging the Z scores of analytic executive tests evaluating information-processing speed (Symbol Digit Modalities Test—Oral version), selective attention (Stroop test) and semantic memory (Verbal Fluency Test).

Results

The FAB detected executive dysfunction in 13.7% of the patients with ALS. Moreover, using the EI standardised cut-off, 37.9% of the patients with ALS showed executive dysfunction. The receiver-operating characteristic curve showed that the optimal cut-off for the FAB in the whole sample was 16, with a sensitivity of 0.889 (95% CIs 0.545 to 1.000), a specificity of 0.593 (95% CI 0.450 to 0.907) and a moderate overall discriminatory power of 0.809. Different levels of respiratory function, duration of disease and depressive symptoms did not affect the FAB validity.

Conclusions

In patients with ALS without dementia, a high prevalence of executive dysfunction was present. The FAB showed good validity as a screening instrument to detect executive dysfunction in these patients and may be used when a complete neuropsychological assessment is not possible.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of this work include relatively stringent criteria for the definition of cognitive impairment, the use of gold standard tests to assess executive dysfunction and a larger sample of patients, as compared with previous studies.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which a tree-based method has been used to evaluate the influence of various demographic and clinical variables on executive dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

A limitation is that our sample was clinically heterogeneous, including patients with an unusually long duration of disease and low disability.

The small number of participants in the final RECursive Partitioning and AMalgamation (RECPAM) analysis, together with the wide SDs, raises the possibility that a larger sample may improve the performance of the frontal assessment battery in more clinically defined subgroups.

The cognitive screening we adopted was limited to executive functions, and it is possible that the dysfunction of more posterior regions of the brain could go undetected.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative illness previously described as a motor disease, but the presence of more complex phenotypes including cognitive and behavioural features is now widely accepted. Cognitive impairment may manifest at the same time as the motor symptoms, or even precede them,1 2 with different degrees of severity, ranging from milder cognitive dysfunction to overt dementia, generally with a frontotemporal pattern.3 The presence of cognitive dysfunction in patients with ALS determines a worse prognosis in terms of life expectancy.4

Few preliminary studies using a screening battery to detect cognitive impairment in ALS have indicated that a brief cognitive screening of these patients can be easily performed in clinical outpatient settings.5 Since cognitive deficits in ALS are largely of executive functioning, the use of a screening tool designed for the detection of frontal dysfunction may be a possible advantageous option.

The frontal assessment battery (FAB)6 7 is a short and easily administered cognitive test that has been shown to be better than the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)8 as a screening tool in neurodegenerative disease with frontal involvement. Few studies have used the FAB9–11 to evaluate frontal lobe dysfunction in ALS, and their findings suggested that the FAB is a quick and reliable method of screening. However, these studies used generally small samples representing different stages of disease and severity. The aims of the present study were to detect executive dysfunction using the FAB in a large sample of patients with ALS without dementia and to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the FAB compared with a standardised extensive neuropsychological assessment of executive functions. Finally, we investigated the association between impairment of executive functions and demographic and clinical features of ALS.

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted according to the World Medical Association’s 2008 Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement12 and STAndards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy (STARD) studies.13 In this retrospective cohort study, we enrolled consecutive patients with ALS attending a specialised multidisciplinary centre for motor neuron disease at the University of Bari ‘Aldo Moro’ in the period between January 2006 and December 2010.

The diagnosis of ALS was based on El Escorial criteria (EEC).14 Patients who had a dementia syndrome according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV Text Revision,15 and participants with an MMSE score lower than 26 were excluded.16 Participants with extreme weakness of the hands and dysarthria were excluded because they were unable to perform the tests. We did not include patients for whom one or more of the neuropsychological tests were unavailable. All the patients with ALS were taking riluzole when they were interviewed for this study. Functional impairment at the neurological examination was evaluated using the revised ALS Functional Rating Scale-revised (ALSFRS-R)17 and manual muscle testing (MMT).18 Respiratory function was measured by forced vital capacity (FVC).19

Neuropsychological assessment

The patients underwent a global screening of executive functions using the Italian version of the FAB.6 7 This consisted of six subset test items: conceptualisation (abstract reasoning), item flexibility (verbal fluency), motor programming (organisation, maintenance and execution of successive actions), sensitivity to interference (conflicting instructions), inhibitory control (inhibit inappropriate responses), and environmental autonomy (prehension behaviour). The administration time of the FAB is about 10 min. Some executive features were also evaluated using three tests commonly used in clinical practice. The first domain was the information-processing speed, possibly determined by attentional capacity (scanning and tracking in the visuospatial domain) and working memory, assessed with the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)—Oral version.20 21 Furthermore, cognitive interference in processing incongruent information preventing habitual or automatic responses was assessed with the Stroop test (ST).22 Finally, the ability to select an appropriate research strategy in lexical access and retrieval was assessed with the Verbal Fluency Test (VFT).23 24 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)25 was administered to evaluate the presence of depressive symptoms. Patients with a BDI score >10 were considered depressed. Two trained neuropsychologists administered to the patients with ALS the FAB or the neuropsychological executive test battery and were blind to the results of other tests.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were reported as frequency (percentages) and mean±SD for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. Standardised Z scores were calculated for all the executive tasks, based on Italian normative data. A cut-off of 2 SD below the mean for standardised data was used to define an abnormal cognitive performance on any task. An ad hoc Executive Index (EI) was defined for each patient by averaging the Z scores of SDMT, the ST items and VFT executive tasks. Patients were categorised as impaired if they had an EI of 2 SD below the mean. Since EI was defined as the mean of four standardised random variables, the computed cut-off of 2 SD below the mean was −1. Correlations between the FAB (total score and its subset of items), EI and the executive tests (SDMT, ST and VFT) were assessed by the Spearman coefficients. Correlations between the FAB total score, EI and demographic and clinical variables were also assessed by the Spearman coefficients. A tree-growing technique, based on the RECursive Partitioning and AMalgamation (RECPAM) algorithm,26 was used to investigate possible interactions among demographic and clinical variables in order to identify distinct and homogeneous patient subgroups in terms of EI. At each partitioning step, the RECPAM method selects the covariate and the best binary split that maximises the difference of EI means between subgroups, following a linear regression model. Age, sex, ALS diagnostic level based on EEC, site of the onset (spinal vs bulbar), education level, disease duration, the degree of disability, BDI, FVC and the mean of MMT were considered as candidate splitting variables. To obtain more robust splits, a bootstrap approach with 100 000 node resampling with replacement was performed. The algorithm stopped when there were less than 14 participants (ie, the minimum leaf size, about 15% of the total sample) within each terminal node (user defined stopping rule). The discriminatory power of the FAB (total score) to detect the patient's executive dysfunction (defined by the EI) was assessed by estimating the Area Under the receiver operating characteristic Curve (AUC)27 and was evaluated both in the overall sample and within each RECPAM class. The optimal cut-off for the FAB was assessed by maximising jointly sensitivity and specificity. Non-parametric bootstrap 95% CIs for optimal specificity and sensitivity were estimated at the optimal cut-off point using 1000 bootstrap samples. Specifically, CIs were derived by using the 2.5 and 97.5 centiles of the bootstrap distribution as the limits of the 95% CI. This approach provided more robust, conservative and validated results.28 A p value<0.05 was considered for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS Release 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

We enrolled a total of 152 consecutive patients with ALS. We excluded 57 patients: 4 patients because of dementia syndrome, 32 due to MMSE<26, 4 for missing neuropsychological tests, and 17 due to weakness in the hands and dysarthria. Therefore, 95 patients with ALS (62 males and 33 females, age range 33–82 years) were included in the analyses. Demographic and clinical data are reported in table 1. Means and SD for the FAB, SDMT, VFT and ST were, respectively, 15.51±2.74, 31.75±13.23, 25.94±9.60 and 27.54±14.92. Executive dysfunction was detected in 88.4% of the patients (n=84) with the VFT, 77.9% (n=74) with the ST and 35.1% (n=33) with the SDMT. Using the EI standardised cut-off, 37.9% of the patients (n=36) showed executive dysfunction. The FAB detected executive dysfunction in 13.7% (n=13) of the patients (cut-off score: 13.5). The FAB total score was significantly correlated with EI (r=0.667, p<0.001) and with each component of EI: SDMT (r=0.610, p<0.001), VFT (r=0.594, p<0.001) and ST (r=−0.434, p<0.001), showing high concurrent validity. Furthermore, the FAB subset-item scores were significantly correlated with the other executive function tests (table 2). A substantial presence of depressive symptoms (BDI score >10) was detected in 45.26% of the patients with ALS (n=43).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical parameters of 95 patients with ALS without dementia

| Variables | Number (%) or mean±SD Median (range) |

|---|---|

| Age, in years | 61.22±10.66 62 (33–82) |

| Sex | |

| Males | 62 (65.26%) |

| Females | 33 (34.74%) |

| Education years | 9.23±3.86 8.00 (0–18) |

| ALS diagnosis | |

| Definite | 33 (34.73%) |

| Probable | 36 (37.89%) |

| Possible | 16 (16.84%) |

| Suspect | 10 (10.52%) |

| Site of onset | |

| Spinal | 85 (89.47%) |

| Bulbar | 10 (10.52%) |

| Time to diagnosis (months) | 16.91±22.99 10.00 (0.34–120) |

| Disease duration (months) | 29.09±30.94 18.00 (2–148) |

| FVC | 86.58±23.33 91.50 (32.4–131.6) |

| MMT | 8.33±1.43 8.60 (2.7–10) |

| ALSFRS-R | 37.29±7.29 39.00 (7–48) |

| BDI | 10.60±7.49 10 (0–29) |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS-R, ALS Functional Rating Scale-revised; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMT, manual muscle testing.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients between the FAB and executive function tests (raw values) in patients with ALS without dementia

| FAB subitems | SDMT | VFT | ST |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptualisation | 0.473 (p<0.001) | 0.361 (p<0.001) | −0.302 (p=0.003) |

| Mental flexibility | 0.457 (p<0.001) | 0.730 (p<0.001) | −0.297 (p=0.004) |

| Motor programming | 0.304 (p=0.003) | 0.174 (p=0.092) | −0.0508 (p=0.625) |

| Sensitivity to interference | 0.317 (p=0.002) | 0.286 (p=0.005) | −0.221 (p=0.031) |

| Inhibitory control | 0.256 (p=0.012) | 0.275 (p=0.007) | −0.370 (p<0.001) |

| Environmental autonomy | 0.108 (p=0.296) | 0.106 (p=0.308) | 0.021 (p=0.837) |

| FAB total score | 0.610 (p<0.001) | 0.594 (p<0.001) | −0.434 (p<0.001) |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; FAB, frontal assessment battery; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test; ST, Stroop Test; VFT, Verbal Fluency Test.

Both the FAB total score and EI correlated with age and respiratory function, while only the FAB total score correlated with disease duration (table 3). Furthermore, we analysed the correlation between the FAB and EI with different levels of respiratory function, disease duration and depressive symptoms. Stratified analysis by respiratory function (FVC: ≤80 vs >80) showed a positive correlation between the FAB and EI in low (r=0.559, p<0.001) and high respiratory function subgroups (r=0.731, p<0.001). Similarly, the analysis by duration of illness (≤18 vs >18 months, median value) showed a positive correlation between the FAB and EI in short (r=0.601, p<0.001) and long disease duration subgroups (r=0.732, p<0.001). When we considered the depressive symptoms in patients with a disease duration of less than 5 years (n=81), the FAB total score was correlated with the tests of EI in both groups depressed (n=47; EI r=0.740, p<0.001; SDMT r=0.773, p<0.001; VFT r=0.756, p<0.001; ST r=−0.435, p=0.002) versus not depressed (n=34; EI r=0.576, p<0.001; SDMT r=0.443, p=0.009; VFT r=0.320, p=0.065; ST r=−0.479, p=0.004). The correlation between the FAB and executive function tests was also present when we restricted the analysis to incident cases (n=35) with disease duration <12 months (EI r=0.665, p<0.001; SDMT r=0.549, p=0.001; VFT r=0.526, p=0.001; ST r=−0.448, p=0.007).

Table 3.

Correlation between demographic, clinical and cognitive variables in patients with ALS without dementia

| Age | Disease duration | FVC | MMT | ALSFRS-R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | ||||

| r=−0.482 | r=−0.055 | r=0.354 | r=0.048 | r=0.094 |

| p<0.001 | p=0.603 | p<0.001 | p=0.656 | p=0.379 |

| FAB | ||||

| r=−0.379 | r=−0.213 | r=0.234 | r=0.130 | r=0.161 |

| p<0.001 | p=0.040 | p=0.024 | p=0.223 | p=0.127 |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS-R, ALS Functional Rating Scale-revised; EI, Executive Index; FAB, frontal assessment battery; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMT, manual muscle testing.

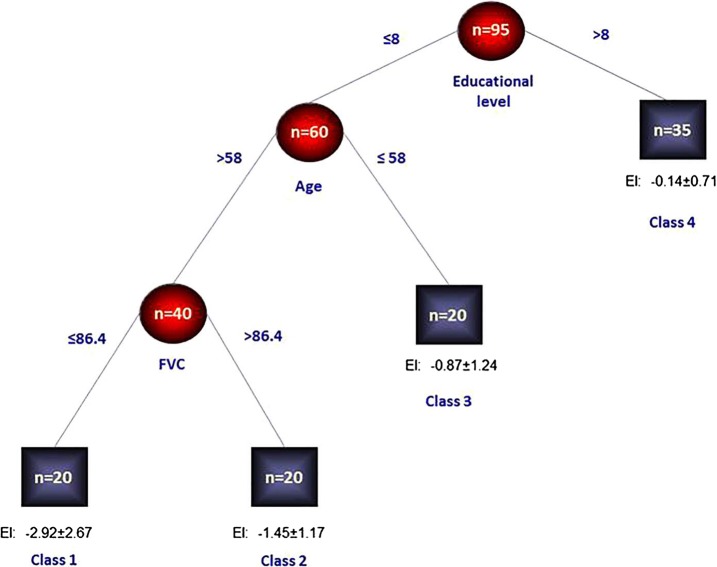

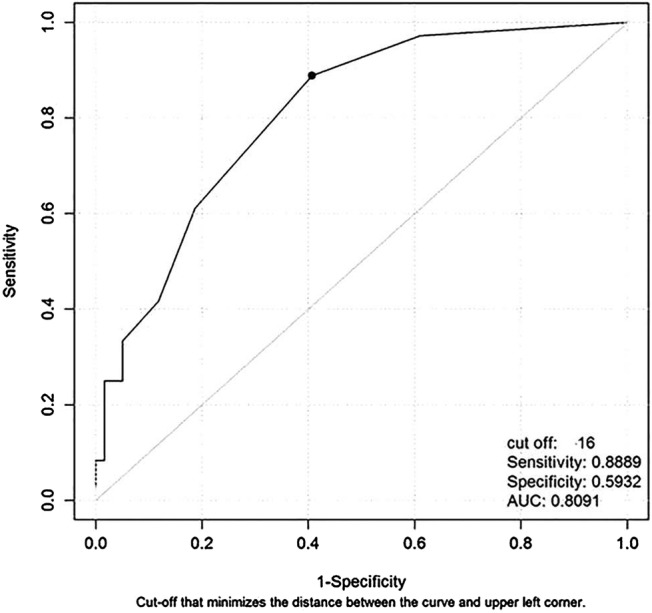

Results of the RECPAM analysis are shown in figure 1. The algorithm identified four homogeneous subgroups of patients in terms of EI means (classes 1–4). Class 1 represented the patient subgroup with the lowest standardised mean EI (and thus with the highest executive cognitive impairment), whereas class 4 represented the patient subgroup with the highest standardised mean EI (and thus with the lowest executive cognitive impairment). Specifically, the algorithm found that patients with an education level ≤8, age >58 years and FVC ≤86.4 represented the class (class 1) with the lowest standardised mean EI (ie, −2.92±2.67, N=20 patients). Patients with an education level ≤8, age >58 years and FVC >86.4 represented the class (class 2) with a quite lower standardised mean EI (ie, −1.45±1.17, N=20 patients). Patients with an education level ≤8 and age ≤58 years represented the class (class 3) with a higher standardised mean EI (ie, −0.87±1.24, N=20 patients), and finally patients with an education level >8 represented the class (class 4) with the highest standardised mean EI (ie; −0.14±0.71, N=35 patients). Furthermore, using the EI standardised cut-off to identify patients with cognitive impairment (gold standard), the optimal cut-off for the FAB (total score) was detected both in the whole sample and within each identified RECPAM class. The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve showed that the optimal cut-off for the FAB in the whole sample was 16 (figure 2). Such a cut-off achieved a high sensitivity of 0.889 (95% CI 0.545 to 1.000), a low specificity of 0.593 (95% CI 0.450 to 0.907), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.571 (95% CI 0.446 to 0.698) and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.897 (95% CI 0.794 to 0.977). The overall discriminatory power (AUC) for the FAB was 0.809. The optimal cut-off for the FAB in patients within each RECPAM class was also assessed. Results are reported in online supplementary figure S1 and in the appendix.

Figure 1.

RECPAM tree. The sample was divided into distinct and homogeneous patients’ subgroups in terms of EI. Splitting variables are shown between branches. The condition sending patient to the right or left is shown on the corresponding branch. Class 4, with the highest EI mean, represents the reference class. Circles indicate subgroups of patients. Squares indicate the patient subgroup RECPAM class. Numbers inside circles and squares represent the number of participants within each class (EI, Executive Index; FVC, forced vital capacity; RECPAM, RECursive Partitioning and AMalgamation).

Figure 2.

ROC curve for the frontal assessment battery index to detect patients with executive dysfunction evaluated in the whole sample (AUC, Area Under the receiver operating characteristic Curve; ROC, receiver-operating characteristic).

Power calculation

A sample of 36 patients with executive dysfunction and 59 patients without executive dysfunction achieved 90% power to detect an overall discriminatory power (AUC) for the FAB (total score) of 0.693, under the null hypothesis of AUC of 0.50, using a two-sided z-test at a significance (α) level of 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, the FAB showed good validity as a screening instrument to detect executive dysfunction in patients with ALS without dementia and to select participants who will undergo a full neuropsychological examination in tertiary centres. The FAB may be especially useful in settings where a complete neuropsychological assessment cannot be proposed because of lack of time or insufficient neuropsychological staff. Respiratory function, disease duration and depressive symptoms did not affect the screening ability of the FAB to detect executive dysfunction. In fact, the correlation between the FAB and other executive tests was present in patients in low and high respiratory function subgroups, assessed in both the early and late stages of disease, and in both depressed and not depressed patients with long disease duration. The assessment of executive functioning showed a high prevalence of cognitive impairment in the executive domain with about 40% of patients with ALS showing executive dysfunction detected with EI.

In this study, the FAB cut-off score of 16 showed an AUC of 0.81, which, according to Swets29 classification (0.7<AUC≤0.9), indicated moderate accuracy. Within each RECPAM class, the AUC ranged from 0.64 in class I with the highest executive cognitive impairment (cut-off score of 16.5) to 0.82 in class 4 with the lowest executive cognitive impairment (cut-off score of 17.5). The optimal FAB cut-off score of 16 for our population is higher than the standard FAB cut-off score for the Italian normative data (13.5),7 reflecting the milder spectrum of executive dysfunction in these patients. We excluded patients with dementia and with serious impairment of the upper limbs. It was also confirmed that executive dysfunction was positively associated with age and respiratory dysfunction, but not with other clinical variables, including measures of functional status. Therefore, age level may have significant effects on the FAB performance in ALS, suggesting that the age of the participants should be taken into consideration in detecting executive dysfunction with this cognitive tool. Furthermore, as reported by other studies, no significant association was found between executive dysfunction and functional status, implying that cognitive impairment was independent from progression of the motor disability and overall disease severity.30 31 Forty-five per cent of our sample had depressive symptoms, confirming how depression may be a common feature in patients with ALS.32–34

The results of this study are overall in keeping with earlier findings, although the majority of previous studies were based on smaller samples.9–11 35 36 Oskarsson et al9 reported an impaired FAB performance in 50% of patients with ALS correlated with disease duration but not with severity of disease, based on a sample size of 16 patients without independent cognitive assessment. A Korean study showed FAB scores indicating executive dysfunction in 22.9% of 61 patients with ALS, associated with disease duration and severity of illness, but with the important limitation of using Italian normative data applied to a Korean population.10 Floris et al11 demonstrated that the FAB has good validity, even in early stages of the disease, using a full neuropsychological battery as the gold standard. However, the sample size was very small (n=20) and correlations with clinical features in ALS were not explored. Another recent Dutch study suggested that the FAB should be administered to patients without moderate or severe speech and motor impairment.35 Finally, the FAB and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) were used to screen frontal lobe and general cognitive impairment in 44 patients with ALS; and while the MoCA classified more patients as cognitively impaired, the FAB was more feasible for assessing patients with physical impairment. Unfortunately, no optimal cut-off scores for these two screening instruments were provided.36

The cognitive phenotype in ALS has not yet been completely defined. At present, the most accredited hypothesis is that in a subgroup of patients with ALS there is early involvement of executive functions with later involvement of other cognitive domains. There are patients, in contrast, who show no signs of cognitive impairment throughout the entire course of the disease.31 The variety of neuropsychological instruments used for the assessments3 31 may be responsible for another piece of the described variability. However, the heterogeneity may be related to the presence of distinct ALS cognitive phenotypes since the early stage of disease. Our study confirms that executive dysfunction may represent a specific cognitive phenotype in a subgroup of patients with ALS. The clinical evidence of overlap between frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and motor neuron disease37–39 has recently gained further support after the C9ORF72 mutation was found to be the most common genetic abnormality in familial and sporadic forms of FTD and ALS, particularly frequent in patients and families with both conditions.40–42 Given the high prevalence of cognitive impairment and behavioural changes in ALS, the evaluation of neuropsychological abilities should be a fundamental part of the multidisciplinary initial assessment for every new patient.3 Extensive neuropsychometry is laborious and requires trained staff explaining why cognitive evaluation as part of the initial assessment is carried out in a limited number of ALS centres. In this study, executive dysfunction, as measured by the EI, assessing primarily access and retrieval lexical and cognitive interference, was present in about one-third of patients without dementia. This is in agreement with other studies that showed that executive dysfunction is the most prominent cognitive deficit in patients with ALS.3 38 In this study, none of the patients in whom the FAB and subsequent full cognitive evaluations indicated the presence of a cognitive impairment had spontaneously reported cognitive dysfunction during the clinical interview. This probably reflects the different relevance of cognitive impairment compared with motor symptoms for the life of patients in the early phases of disease.

There are a number of limitations in this study. Our sample was enrolled in a tertiary centre that is similar to other referral centres for these main characteristics: long disease duration, less functional impairment, relatively younger patients, and a higher prevalence of spinal onset compared with bulbar onset. Furthermore, the retrospective design of this study may have several pitfalls, including the lack of assessment of certain prognostic factors, such as symptoms progression rate, the less-accurate diagnosis usually based only on the retrospective revision of clinical data, and the risk of missing specific subsets of patients with ALS not captured by the study design. Our sample was also clinically heterogeneous including patients with an unusually long duration of disease and low disability. Other possible sources of heterogeneity such as psychosocial factors (ie, perceived stress, marital status or anger expression) or malnourishment, a relevant determinant of cognitive function in ALS, have not been addressed in this study. The small number of participants in the final RECPAM analysis, together with the wide SDs, raises the possibility that a larger sample may improve the performance of the FAB in more clinically-defined subgroups. Finally, the cognitive screening we adopted was limited to executive functions, and it is possible that dysfunction of more posterior regions could go undetected. The strengths of this work include relatively stringent criteria for the definition of cognitive impairment, the use of gold standard tests to assess executive dysfunction and a larger sample of patients, as compared with previous studies.9–11 30 34 35 Also, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a tree-based RECPAM analysis (a generalisation of Classification And Regression Tree (CART)) has been used to study the influence of various demographic and clinical variables on cognitive dysfunction in ALS. Tree-based methods are well-established techniques to address interactions detection and subgroup analyses, as well as to derive internally validated cut-off for continuous predictors which could not be necessarily linear.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that the FAB had good diagnostic accuracy for detecting executive dysfunction in a population of patients with ALS without dementia and severe impairment of upper limbs referred to a tertiary centre. It should be stressed that the use of such screening instruments should not preclude a complete neuropsychological evaluation focused on executive functions, as well as on other cognitive domains such as language and visuospatial abilities. In patients with ALS, a recent and suitable cognitive tool to screen all cognitive domains is the Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS).43 However, the ECAS was designed to detect the profile of cognitive and behavioral changes in ALS and was not specifically focused on executive functions. In fact, the ECAS evaluates five cognitive (social cognition, language, fluency, memory, and visuospatial functions), and five behavioural domains, characterising FTD.42 With the recent emphasis on the genetic and clinical overlap between motor neuron disease and FTD, systematic cognitive screening of patients with ALS would facilitate longitudinal studies that are much needed to clarify the different clinical patterns of disease, including prognosis and their different biological substrates.

Footnotes

Contributors: MRB, FP and GL contributed to the concept of the study and are guarantors. MRB, FP and GL also contributed to the interpretation of the data and coordinated the manuscript preparation. AF, MC and GL completed the statistical analysis. SB, AI, RT, RC and ILS contributed to further interpretations and commenting on drafts of the manuscript in its preparation. MRB, GL, FP, AF and MC had full access to all of the data in the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, read and commented on the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Funding: This research was in part supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013 under grant agreement 259867).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of ‘Azienda Ospedaliera, Ospedale Policlinico Consorziale, Bari, Italy’.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Strong MJ, Grace GM, Orange JB et al. A prospective study of cognitive impairment in ALS. Neurology 1999;53:1665–70. 10.1212/WNL.53.8.1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lomen-Hoerth C, Murphy J, Langmore S et al. Are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients cognitively normal? Neurology 2003;60:1094–7. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000055861.95202.8D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strong MJ, Grace GM, Freedman M et al. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of frontotemporal cognitive and behavioural syndromes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:131–46. 10.1080/17482960802654364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elamin M, Phukan J, Bede P et al. Executive impairment is a negative prognostic indicator in ALS patients without dementia. Neurology 2011;76:1263–9. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318214359f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon PH, Wang Y, Doorish C et al. A screening assessment of cognitive impairment in patients with ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2007;8:362–5. 10.1080/17482960701500817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I et al. The FAB: Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 2000;55:1621–6. 10.1212/WNL.55.11.1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apollonio I, Leone M, Isella V et al. The frontal assessment battery (FAB): normative values in an Italian population sample. Neurol Sci 2005;26:108–16. 10.1007/s10072-005-0443-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh P. ‘Mini-mental state’: a practical method for grading the cognition of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res 1975;12:189–98. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oskarsson B, Quan D, Rollins YD et al. Using the Frontal Assessment Battery to identify executive function impairments in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a preliminary experience. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2010;11:244–7. 10.3109/17482960903059588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn SW, Kim SH, Kim JE et al. Frontal assessment battery to evaluate frontal lobe dysfunction in ALS patients. Can J Neurol Sci 2011;38:242–6. 10.1017/S0317167100011409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floris G, Borghero G, Chiò A et al. Cognitive screening in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in early stages. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:95–101. 10.3109/17482968.2011.605453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. , STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. , Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:W1–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks BR, World Federation of Neurology Sub-Committee on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial WFN criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1994;124:965–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR). 4th edn Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magni E, Binetti G, Bianchetti A et al. Mini-Mental State Examination: a normative study in Italian elderly population. Eur J Neurol 1996;3:1–5. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.1996.tb00423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS Functional Rating Scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (phase III). J Neurol Sci 1999;169:13–21. 10.1016/S0022-510X(99)00210-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Great Lakes ALS Study Group. A comparison of muscle strength testing techniques in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2003;61:1503–7. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000095961.66830.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czaplinski A, Yen AA, Appel SH. Forced vital capacity (FVC) as an indicator of survival and disease progression in an ALS clinic population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:390–2. 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nocentini U, Giordano A, Di Vincenzo S et al. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test—Oral Version: Italian normative data. Funct Neurol 2006;21:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caffarra P, Vezzadini G, Dieci F et al. Una versione abbreviata del test di Stroop: dati normativi nella popolazione Italiana. Riv Neurol 2002;12:111–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination manual. Iowa City: University of Iowa, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Gainotti G. The Mental deterioration Battery: normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. The Group for the Standardization of Mental Deterioration Battery. Eur Neurol 1996;36:378–84. 10.1159/000117297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muscarella LA, Barbano R, D'Angelo V et al. Regulation of KEAP1 expression by promoter methylation in malignant gliomas and association with patient's outcome. Epigenetics 2011;6:317–25. 10.4161/epi.6.3.14408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982;143:29–36. 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swets JA. Signal detection theory and ROC analysis in psychology and diagnostics: collected papers. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terada T, Obi T, Miyajima H et al. Assessing frontal lobe function in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by frontal assessment battery. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2010;50:379–84. 10.5692/clinicalneurol.50.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phukan J, Elamin M, Bede P et al. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:102–8. 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atassi N, Cook A, Pineda CM et al. Depression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011;12:109–12. 10.3109/17482968.2010.536839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurt A, Nijboer F, Matuz T et al. Depression and anxiety in individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs 2007;21:279–91. 10.2165/00023210-200721040-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wicks P, Abrahams S, Masi D et al. Prevalence of depression in a 12-month consecutive sample of patients with ALS. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:993–1001. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raaphorst J, Beeldman E, Jaeger B et al. Is the Frontal Assessment Battery reliable in ALS patients? Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2013;14:73–4. 10.3109/17482968.2012.712974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osborne RA, Sekhon R, Johnston W et al. Screening for frontal lobe and general cognitive impairment in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2014;336:191–6. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lomen-Hoerth C, Anderson T, Miller B. The overlap of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2002;59:1077–9. 10.1212/WNL.59.7.1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhingholz GM, Appel SH, Bradshaw M et al. Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurology 2005;65:586–90. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172911.39167.b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lillo P, Savage S, Mioshi E et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a behavioural and cognitive continuum. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:102–9. 10.3109/17482968.2011.639376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011;72:257–68. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011;72:245–56. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byrne S, Elamin M, Bede P et al. Cognitive and clinical characteristics of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis carrying a C9orf72 repeat expansion: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:232–40. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70014-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrahams S, Newton J, Niven E et al. Screening for cognition and behaviour changes in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2014;15:9–14. 10.3109/21678421.2013.805784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]