Abstract

Objective

When testing physical function, patients must be alert and have the capacity to understand and respond to instructions. Patients with dementia may have difficulties fulfilling these requirements and, therefore, the reliability of the measures may be compromised. We aimed to assess the inter-rater reliability between pairs of observers independently rating the participant in the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), 30 s chair stand test (CST) and 6 m walking test. We also wanted to investigate the internal consistency of the BBS.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

We included 33 nursing home patients with a mild-to-moderate degree of dementia and tested them once with two evaluators present. One evaluator gave instructions and both evaluators scored the patients’ performance. Weighted κ, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) model 2.1 with 95% CIs and minimal detectable change (MDC) were used to measure inter-rater reliability. Cronbach's α was calculated to evaluate the internal consistency of the BBS sum score.

Results

The mean values of the BBS scored by the two evaluators were 38±13.7 and 38.0±13.8, respectively. Weighted κ scores for the BBS items varied from 0.83 to 1.0. ICC for the BBS's sum score was 0.99, and the MDC was 2.7% and 7%, respectively. The Cronbach’s α of the BBS's sum score was 0.9. The ICC of the CST and 6 m walking test was 1 and 0.97, respectively. The MDC on the 6 m walking test was 0.08% and 15.2%, respectively.

Conclusions

The results reveal an excellent relative inter-rater reliability of the BBS, CST and 6 m walking test as well as high internal consistency for the BBS in a population of nursing home residents with mild-to-moderate dementia. The absolute reliability was 2.7 on the BBS and 0.08 on the 6 m walking test.

Keywords: GERIATRIC MEDICINE, REHABILITATION MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study included a well-defined population of older people living in a nursing home and scoring 1 or 2 on a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale.

Three commonly used clinical tests were evaluated.

The number of participants was limited.

Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of people with dementia is estimated to nearly double every 20 years, reaching 40.8 million in 2020 and 90.3 million in 2040.1 Dementia affects balance, mobility and gait performance,2–4 and people with dementia have a twofold increased risk of falls compared to non-demented elderly.5 Even though the literature is unequivocal, studies show important benefits through exercise and physical activity for older adults with dementia in areas of physical health, including activities of daily living (ADL) and of mental health.6–9 Consequently, physical therapists are likely to be treating an increasing number of people with dementia.10 For this reason, the demand for reliable and valid measures to assess physical function in these patients will increase.11 According to Hauer and Oster,12 testing of physical function assumes that test participants are able to (1) comprehend the test commands, (2) develop an adequate physical action and sequence and (3) remember both during execution of the test. Another prerequisite is that test participants show adequate attention during testing. The presence of dementia will influence these factors and could thereby affect reliability.

The lack of reliability tested physical function instruments for nursing home patients with dementia has been repeatedly expressed in the literature.13 14 To the best of our knowledge, only one other study has investigated the reliability of the BBS in a population of nursing home residents.15 In that study, 67% had dementia. They demonstrated a high ICC value but a relatively low-absolute reliability (minimal detectable change) of 7.7 points. However, inter-rater reliability was not tested. Suttanon et al,16 found that the reliability of different mobility and balance measures ranged between fair to excellent in a population of mostly community dwelling elderly people with Alzheimer's disease. The authors stressed the importance of considering reliability when deciding which balance and mobility measures to use for this group.

Three functional tests were investigated in this study: the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), 30 s chair stand test (CST) and 6 m walking test. Balance is often impaired in older people with dementia, and improvement in balance is an important goal of rehabilitation.17 Measuring balance can assist the clinician in selecting the most appropriate therapy and outcome measurement.18 19 The BBS is used extensively in the clinic, has frequently been compared with other balance measures and is considered to be the gold standard of measuring balance.20 21 The BBS has been found to have a high intrarater and inter-rater reliability, but variable absolute reliability.22 The 30 s CST is one of the most important functional evaluation clinical tests because it measures lower body strength and relates it to the most demanding daily life activities.23 24 Lower limb muscle weakness has been identified as a risk factor for falls and for the inability to perform lower extremity functional tasks such as walking, sitting-to-standing transfers, climbing steps and lower body dressing.25–27 Walking speed is associated with reduced balance ability and increased risk of falling. It can predict health status, survival and hospital costs.28–30 Walking speed tests are frequently used to evaluate mobility in elderly people.31 32

Test-retest reliability has been more frequently investigated than inter-rater reliability.10 33 However, during rehabilitation, an elderly patient may be assessed by more than one physiotherapist, and high reliability between scorings made by different evaluators are therefore essential. This is also important when testing in multicentre research projects. We aimed to assess the inter-rater reliability between pairs of observers independently rating the participant in BBS, CST and 6 m walking test. We also wanted to assess the internal consistency of the BBS.

Methods

Participants

We included 33 participants residing in four different nursing homes in the area around Oslo, Norway. They were recruited from a randomised controlled trial that aimed to investigate the effect of a high-intensity exercise programme in nursing home residents with dementia. The inclusion criteria were: being above 55 years of age, having dementia to a mild or moderate degree, as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR 1 or 2), being able to stand up alone or with the help of one person and being able to walk 6 m with or without a walking aid. The exclusion criteria were: patients being medically unstable, psychotic or having severe communication problems. Details about the participants can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Women, n (%) | 25 (75.8) |

| Age, mean (SD), range | 82.7 (7.2), 66–91 |

| Length of stay in nursing home (months), mean (SD), range | 22 (27.8), 3–111 |

| Neurological disease n (%) | 9 (27.3) |

| Heart disease n (%) | 19 (57.6) |

| Musculoskeletal disease n (%) | 9 (27.3) |

| MMSE-score mean (SD), range | 15.8 (5.4), 0–51 |

| CDR=1 n (%) | 13 (39.4%) |

| Barthel Index, mean (SD), range | 13.1 (4.4), 3–20 |

| Walked independently n (%) | 10 (30.3) |

| Walked independently during 6 m walking test n (%) | 16 (50) |

| Number of diagnosis, mean (SD), range | 3.1 (1.8), 1–8 |

| Number of medications, mean (SD), range | 6 (3.0), 0–13 |

CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

Procedure

The study was carried out by two physiotherapists. The examiners were trained in the standardised instructions of the tests and had experience from testing 120 patients in a study 3 months earlier. The patients were tested only once, in the following order: the BBS first, followed by the CST and 6 m walking test; the whole test procedure took about 30 min. The two physiotherapists scored the test performance simultaneously without knowledge of each other's rating (‘blind’), and alternated between instructing the participant and observing the patient. In this way, they both administered the test in half of the patient population. The reason for choosing this model was: some of the participants were undergoing rehabilitation and could have improved, and if they had been tested on two different days within a week, their performance could have changed and, thus, test-retest reliability would have been biased. Certain steps were taken to optimise communication with the participants on all tests.34 The progression of cueing was predefined and based on suggestions by Vogelpohl et al.35 The first step was verbal cueing, which progressed to demonstrating/mirroring, and then to tactile guidance and physical assistance.

Instruments

The BBS is a performance-based instrument originally developed by Berg et al36 for assessment of functional balance in older adults. The BBS assesses performance on five levels, from 0 (cannot perform) to 4 (normal performance), on 14 different tasks involving functional balance control, including transfer, turning and stepping, giving a score between 0 (poor) and 56 (normal). It takes 15–20 min to complete. We used the Norwegian version of the test.37

The 30 s CST measures lower limb muscle strength. The score equals the number of rises from a chair in 30 s with arms folded across the chest.23 During performance of the 6 m walking test the participant walks 6 m at comfortable speed with or without a walking aid. The time in seconds was recorded and calculated to metres per second.38

To measure the patients’ dependence/independence in the ADL, we employed the Barthel Index (BI), a widely used questionnaire for assessing ADL.39 40 The CDR Scale and the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) were used to measure cognition. We used the CDR to validate the dementia diagnosis of the patients. Two Norwegian studies have shown that CDR staging is a valid substitute for dementia assessment among nursing-home patients, to rate dementia and dementia severity.41 42 The MMSE was used to assess global cognition and consists of 20 items concerning orientation, word registration and recall, attention, naming, reading, writing, following commands and figure copying.43 Information about the participants’ medical history was obtained from their medical records.

Ethics

Written and verbal information about the study was given to the patients and their relatives by their primary caregiver. All the participants gave written consent to participate and were informed that they could refuse to participate at any stage in the study.

Statistics

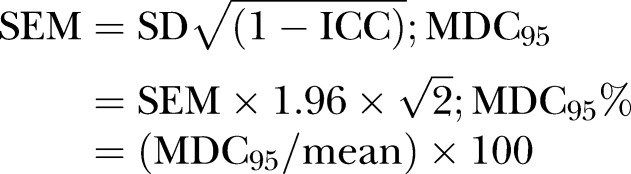

Inter-rater reliability for the sum score of the BBS, CST and 6 m walking test was measured with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) in SPSS V.22. The ICC quantifies the relative reliability where the relationship between two or more sets of measurements is examined. An ICC of 1 corresponds to perfect agreement. An ICC of 0.8 or higher reflects high relative reliability, between 0.6 and 0.8 moderate reliability and less than 0.6 indicates poor reliability.44 According to Shrout and Fleiss, 1979, the ICC category in the current study was case 2 because the evaluators are considered to be a random sample from a population of potential raters.45 To test absolute reliability we calculated SEM, minimal detectable change (MDC)95 and MDC95%.46

|

Inter-rater agreement on individual items of the BBS was analysed with weighted κ. The weighted κ score measures the agreement among raters, adjusted for the amount of agreement expected by chance and the magnitude of disagreement.47 A κ value of 0.75 or higher indicates excellent agreement, between 0.4 and 0.74 indicates fair to low agreement and less than 0.4 indicates poor agreement.48 Weighted κ was calculated in Excel V.2011 for Mac with Real Statistics Resource Pack. Cronbach's α for each evaluator's scorings were calculated to assess the internal consistency of the BBS. Cronbach's α is regarded as excellent when it is higher than 0.9, as good between 0.7 and 0.9 and as acceptable between 0.6 and 0.7.49 Internal consistency of the BBS was also tested by item-to-total correlation. An item-to-total correlation shows the degree of association between each individual item and the total score of the other items in the scale. An item-to-total correlation is considered adequate if it is above 0.4.44

Results

Demographic characteristics

Thirty-three nursing home residents (25 women, 8 men) with mild-to-moderate dementia participated in this study. Mean stay at the nursing home was almost 2 years, however, it ranged between 3 months and 9 years. Four of the participants used a wheelchair, and 17 used Zimmer frames to move about. The most common neurological diseases among the participants were stroke (n=3) and migraine (n=3). The most common heart diseases were hypertension (n=10), atrial fibrillation (n=4) and angina pectoris (n=3), and most common musculoskeletal diseases were osteoporosis (n=4) and arthritis in the knee or hip (n=2). Characteristics are presented in table 1.

Distribution of scores

The mean total score ±SD of the BBS was similar between the evaluators (table 2). Table 3 demonstrates the distributions on the BBS for each evaluator. The table shows the number of patients with a score of zero, one, two, three and four on each item. On the CST, the two evaluators scored identically. On average, the participants walked 6 m in 12 s, which equals a speed of 0.5 m/s.

Table 2.

ICC of BBS, CST and 6 m walking test

| Test | Tester | Mean (SD) | Range | ICC | SEM | MDC | MDC % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBS | Tester 1 | 38.0 (13.8) | 0–51 | 0.995 | 0.97 | 1.92 | 7 |

| Tester 2 | 38.0 (13.7) | 0–51 | |||||

| 30 s chair stand | Both testers | 6 (3.2) | 0–12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 m walking test | Tester 1 | 0.53 (0.16) | 0.22–0.84 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 15.2 |

| Tester 2 | 0.53 (0.18) | 0.12–0.82 |

BBS, Berg Balance Scale; CST, chair stand test; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MDC, minimal detectable change.

Table 3.

Distribution of Berg Balance Scale scores from each evaluator: evaluator 1 (E1) and evaluator 2 (E2)

| Items | 0 point |

1 point |

2 points |

3 points |

4 points |

Mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | E2 | E1 | E2 | E1 | E2 | E1 | E2 | E1 | E2 | ||

| 1. Sitting to standing | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 19 | 19 | 3.2 |

| 2. Standing unsupported | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 28 | 3.5 |

| 3. Sitting unsupported | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 32 | 3.9 |

| 4. Standing to sitting | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 3.3 |

| 5. Transfers | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 3.1 |

| 6. Standing with eyes closed | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 27 | 3.4 |

| 7. Standing with feet together | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 15 | 2.4 |

| 8. Reaching forward with outstretched arm | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 14 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 2.2 |

| 9. Retrieving object from floor | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 26 | 26 | 3.2 |

| 10. Turning to look behind | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 14 | 13 | 2.7 |

| 11. Turning 360° | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 2.0 |

| 12. Placing alternate foot on stool | 11 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 1.8 |

| 13. Standing with one foot extended | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 19 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 |

| 14. Standing on one foot | 6 | 7 | 24 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Total | 68 | 69 | 35 | 37 | 64 | 61 | 88 | 84 | 207 | 211 | 38.0 |

Inter-rater reliability

Weighted κ scores for each of the 14 items on the BBS obtained by the evaluators varied from 0.83 to 1 (table 4). On the BBS, the evaluators scored differently on only 32 occasions of the total 462, which gives an agreement per cent of 93.1. ICC for the BBS's sum score was very high. The MDC indicates that a change score of almost three points can be caused by the effect of being tested by a different evaluator and not necessarily clinical change. The CST had an ICC of 1, while the 6 m walking test ICC score was 0.98 with an MDC of 0.47 (table 2).

Table 4.

Weighted κ of the individual items of the BBS

| Items | Weighted κ between testers |

|---|---|

| 1. Sitting to standing | 1.00 |

| 2. Standing unsupported | 1.00 |

| 3. Sitting unsupported | 1.00 |

| 4. Standing to sitting | 0.93 |

| 5. Transfers | 0.95 |

| 6. Standing with eyes closed | 0.93 |

| 7. Standing with feet together | 0.96 |

| 8. Reaching forward with outstretched arm | 0.87 |

| 9. Retrieving object from floor | 0.89 |

| 10. Turning to look behind | 0.83 |

| 11. Turning 360° | 0.84 |

| 12. Placing alternate foot on stool | 0.83 |

| 13. Standing with one foot extended | 0.94 |

| 14. Standing on one foot | 0.94 |

| All items | 0.94 |

Construct validity

Cronbach's α coefficient of the BBS was 0.948. The correlation matrices, which included the 14 items of the BBS and sum score, are presented in table 5. The item-to-total correlations were r>0.4 for all items except item 3. The scores were very uniform on item three: one participant scored 0 and the rest scored 4 points.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix

| BBS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | 0.89** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 0.45** | 0.51** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 0.84** | 0.90** | 0.51** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5 | 0.91** | 0.90** | 0.45** | 0.85** | 1 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.86** | 0.81** | 0.44* | 0.75** | 0.80** | 1 | ||||||||

| 7 | 0.54** | 0.60** | 0.26 | 0.52** | 0.54** | 0.4* | 1 | |||||||

| 8 | 0.79** | 0.64** | 0.34 | 0.63** | 0.67** | 0.69** | 0.44* | 1 | ||||||

| 9 | 0.77** | 0.81** | 0.37* | 0.70** | 0.74** | 0.68** | 0.51** | 0.62** | 1 | |||||

| 10 | 0.70** | 0.69** | 0.34 | 0.66** | 0.73** | .059** | 0.50** | 0.63** | 0.85** | 1 | ||||

| 11 | 0.59** | 0.54** | 0.27 | 0.53** | 0.66** | 0.39* | 0.50** | 0.44* | 0.38* | 0.61** | 1 | |||

| 12 | 0.57** | 0.49** | 0.22 | 0.45** | 0.60** | 0.42* | 0.49** | 0.45** | 0.63** | 0.66** | 0.47** | 1 | ||

| 13 | 0.84** | 0.77** | 0.38* | 0.65** | 0.79** | 0.91** | 0.53** | 0.74** | 0.66** | 0.58** | 0.39* | 0.48** | 1 | |

| 14 | 0.53** | 0.63** | 0.28 | 0.47** | 0.55** | 0.51** | 0.59** | 0.46** | 0.57** | 0.55** | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.60** | 1 |

| Sum | 0.93** | 0.92** | 0.50** | 0.86** | 0.93** | 0.83** | 0.68** | 0.78** | 0.86** | 0.84** | 0.66** | 0.68** | 0.84** | 0.65** |

*p<0.05.

**p<0.01.

BBS, Berg Balance Scale.

Discussion

The weighted κ in the current study ranged between 0.83 and 1, indicating an excellent inter-rater reliability when using the BBS in a population of nursing home residents with dementia. These results fit well with the results from studies on other populations.36 50–52 The ICC of the BBS sum score was very high, which also concurs with studies on multiple sclerosis-patients52 and lower limb amputees.53 In the current study, the MDC was 2.7, which means that one must allow for a difference in almost 3 points between evaluators. In agreement with other studies,37 52 our findings indicate a high internal consistency of the BBS. All of the item-to-total correlation coefficients were 0.6 or above (except item number 3 because of little variability within scores). The high internal consistency of the BBS showed that the items of this instrument measured the same concept. Some of the items showed fairly high correlation, and a few correlation coefficients exceeded 0.9, which may indicate item redundancy. This should be investigated further.

In our study, the mean value of BBS was 38 points. A study from three nursing homes in Sweden demonstrated a mean BBS score of 30 points.15 Reasons for this discrepancy may be that our participants took part in an exercise study and therefore were more fit than the general nursing home population, and that we had somewhat stricter inclusion criteria regarding physical function. However, the current population had a lower mean MMSE score (16 points) than the Swedish study (17.5 points). It is interesting to note that even when testing a fitter group of nursing home residents, there does not seem to be a ceiling effect of the BBS, as none of the participants scored the maximum amount of points on it.54 Only one participant scored 0 points, which means no floor effect was detected for this population. Floor and ceiling effect have been shown in other studies.51 55 Our results concur with the results of Halsaa et al.37

The ICC of the 6 m walking test was also very high, and this has been found in similar populations by others.56 Their study demonstrated high inter-rater reliability for both the 4 and 6 m walking test, with ICC of 0.96 and 0.88, in a group of elderly participants with cognitive impairment from both a day centre and a nursing home. The participants in the current study scored lower on the CST (6±3.2) than a similar population in a study by Blankevoort et al13: 8.1±2.95. They also had a slower walking speed, 0.5 m/s±0.2 versus 0.8±0.3 m/s, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, inter-rater reliability has never before been investigated on the CST. In our study, the two evaluators scored identically on the CST. Discrepancies in interpretation of when not to approve repetitions (participant fails to fully extend hip/knee or does not sit down between counts) were expected, but the two evaluators agreed in all 33 performances. Both the CST and 6 m walking test have been found to have good test-retest reliability in a similar population of elderly people with dementia, living at home or in a nursing home, with a mean MMSE score of 19 (range 10–28).13

Limitations of the study

We had a relatively small sample size; nevertheless, there was sufficient information to make interesting observations in a population not frequently included in research studies. One limitation of the study is that the inclusion criteria restrict our findings to nursing home residents who can rise from a chair with one person's help and who are able to walk 6 m with or without a walking aid. Even though some of the participants used an electrical wheel chair and managed to move 6 m only with the help of walking aids, this means that the frailest have not been included. In the clinic there may be more than two raters, therefore it may be considered a limitation that this study only investigated the use of two evaluators. The evaluations were performed simultaneously. This may lead to an overestimation of reliability due to the fact that one evaluator watches the other evaluator instruct and score. The second evaluator may thereby gain information about the instructor's scoring through watching his/her positioning, body language or choice of words.

Implications for practice

This study indicates that the BBS, 30 s CST and 6 m walking test have very good inter-rater reliability in older people with dementia living in nursing homes, and that the tests can be used both in research and for clinical purposes, to assess physical functioning. Studies report that older individuals with cognitive impairments benefit from exercise regimens.7 57 Our study shows that patients with mild-to-moderate dementia are able to take instructions, which makes reliable assessments possible.

Conclusion

The results reveal an excellent relative inter-rater reliability of the BBS, CST and 6 m walking test, as well as high internal consistency for the BBS, in a population of nursing home residents with mild-to-moderate dementia. The absolute reliability was 2.7 on the BBS and 0.08 on the 6 m walking test.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Elisabeth Telenius at @#bissilissi

Contributors: EWT, KE and AB participated in contribution to the design of the study, accountability for all aspects of the work and approval of the published version. EWT was involved in drafting of the work. KE and AB were responsible for revising the work.

Funding: This study is funded by the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Ethics in south east of Norway on 5 September 2012.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E et al. . The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:63–75 e2. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Doorn C, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S. Dementia is a risk factor for falls and fall injuries among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1213–18. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman HH, Van Baelen B, Kavanagh SM et al. . Cognition, function, and caregiving time patterns in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease: a 12-month analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2005;19:29–36. 10.1097/01.wad.0000157065.43282.bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazoteras Munoz V, Van Kan GA, Cantet C et al. . Gait and balance impairments in Alzheimer disease patients. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:79–84. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181c78a20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E et al. . Risk factors for serious injury during falls by older persons in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:1214–21. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A et al. . Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease: a 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:158–65. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forbes D, Thiessen EJ, Blake CM et al. . Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;12:CD006489 10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thuné-Boyle ICV, Iliffe S, Cerga-Pashoja A et al. . The effect of exercise on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: towards a research agenda. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1046–57. 10.1017/S1041610211002365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Littbrand H, Stenvall M, Rosendahl E. Applicability and effects of physical exercise on physical and cognitive functions and activities of daily living among people with dementia: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2011;90:495–518. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318214de26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ries JD, Echternach JL, Nof L et al. . Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change scores for the timed “up & go” test, the six-minute walk test, and gait speed in people with Alzheimer disease. Phys Ther 2009;89:569–79. 10.2522/ptj.20080258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips CD, Chu CW, Morris JN et al. . Effects of cognitive impairment on the reliability of geriatric assessments in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:136–42. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauer K, Oster P. Measuring functional performance in persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:949–50. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blankevoort CG, Van Heuvelen MJ, Scherder EJ. Reliability of six physical performance tests in older people with dementia. Phys Ther 2013;93:69–78. 10.2522/ptj.20110164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox B, Henwood T, Neville C. Reliability of functional performance in older people with dementia. Australas J Ageing 2013;32:248–9. 10.1111/ajag.12069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conradsson M, Lundin-Olsson L, Lindelof N et al. . Berg balance scale: intrarater test-retest reliability among older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilities. Phys Ther 2007;87:1155–63. 10.2522/ptj.20060343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suttanon P, Hill KD, Dodd KJ et al. . Retest reliability of balance and mobility measurements in people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23:1152–9. 10.1017/S1041610211000639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur J, Garnawat D, Bhatia MS, et al. Rehabilitation in Alzheimer's disease. Dehli Psychiatry J 2013;16:166–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohannon RW, Leary KM. Standing balance and function over the course of acute rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995;76:994–6. 10.1016/S0003-9993(95)81035-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade DT, Collen FM, Robb GF et al. . Physiotherapy intervention late after stroke and mobility. BMJ 1992;304:609–13. 10.1136/bmj.304.6827.609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langley F, Mackintosh S. Functional balance assessment of older community dwelling adults: a systematic review of the litterature. Internet J Appl Health Sci Pract 2007;5:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyson S, Desouza L. A systematic review of methods to measure balance and walking post stroke. Phys Ther Rev 2002;7:173–86. 10.1179/108331902235001589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Downs S, Marquez J, Chiarelli P. The Berg Balance Scale has high intra- and inter-rater reliability but absolute reliability varies across the scale: a systematic review. J Physiother 2013;59:93–9. 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70161-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 1999;70:113–19. 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millor N, Lecumberri P, Gómez M et al. . An evaluation of the 30-s chair stand test in older adults: frailty detection based on kinematic parameters from a single inertial unit. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2013;10:86 10.1186/1743-0003-10-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azegami M, Ohira M, Miyoshi K et al. . Effect of single and multi-joint lower extremity muscle strength on the functional capacity and ADL/IADL status in Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Nurs Health Sci 2007;9:168–76. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puthoff ML, Nielsen DH. Relationships among impairments in lower-extremity strength and poser, functional limitations and disability in older adults. Phys Ther 2007;87:1334–47. 10.2522/ptj.20060176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki M, Kirimoto H, Inamura A et al. . The relationship between knee extension strength and lower extremity functions in nursing home residents with dementia. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:202–9. 10.3109/09638288.2011.593678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purser JL, Weinberger M, Cohen HJ et al. . Walking speed predicts health status and hospital costs for frail elderly male veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005;42:535–46. 10.1682/JRRD.2004.07.0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy SE, Perera S, Roumani YF et al. . Improvement in usual gait speed predicts better survival in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1727–34. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumurgier J, Elbaz A, Ducimetiere P et al. . Slow walking speed and cardiovascular death in well functioning older adults: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b4460 10.1136/bmj.b4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Assessing the building blocks of function: utilizing measures of functional limitation. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:112–21. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang CY, Yeh CJ, Hu MH. Mobility-related performance tests to predict mobility disability at 2-year follow-up in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;52:1–4. 10.1016/j.archger.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas VS, Hageman PA. A preliminary study on the reliability of physical performance measures in older day-care center clients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2002;14:17–23. 10.1017/S1041610202008244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalmers J. Behaviour management and communication strategies for dental professionals when caring for patients with dementia. Spec Care Dentist 2000;20:147–54. 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2000.tb01152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogelpohl TS, Beck CK, Heacock P et al. . “I can do it!” Dressing: promoting independence through individualized strategies. J Gerontol Nurs 1996;22:39–42; quiz 48 10.3928/0098-9134-19960301-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg K, Beck CK, Heacock P et al. . Measuring balance in the elderly: preliminary development of an instrument. Physiother Can 1989;41:304–11. 10.3138/ptc.41.6.304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halsaa KE, Brovold T, Graver V et al. . Assessments of interrater reliability and internal consistency of the Norwegian version of the Berg Balance Scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:94–8. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D et al. . Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:314–22. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S et al. . The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:61–3. 10.3109/09638288809164103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nygaard HA, Ruths S. Missing the diagnosis: senile dementia in patients admitted to nursing homes. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:148–52. 10.1080/02813430310001798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engedal K, Haugen PK. The prevalence of dementia in a sample of elderly Norwegians. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1993;8:565–70. 10.1002/gps.930080706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altman D. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stratford P. Getting more from the literature: estimating the standard error of measurement from reliability studies. Physiother Can 2004;56:27–30. 10.2310/6640.2004.15377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213–20. 10.1037/h0026256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleiss J. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd edn New York: John Wiley, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 49.George D, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows step by step: a simple guide and reference. 11.0 update 4th edn Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ottonello M, Ferriero G, Benevolo E et al. . Psychometric evaluation of the Italian version of the Berg Balance Scale in rehabilitation inpatients. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2003;39:181–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noren AM, Bogren U, Bolin J et al. . Balance assessment in patients with peripheral arthritis: applicability and reliability of some clinical assessments. Physiother Res Int 2001;6:193–204. 10.1002/pri.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Azad A, Taghizadeh G, Khaneghini A. Assessments of the reliability of the Iranian version of the Berg Balance Scale in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2011;20:22–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong CK. Interrater reliability of the Berg Balance Scale when used by clinicians of various experience levels to assess people with lower limb amputations. Phys Ther 2014;94:371–8. 10.2522/ptj.20130182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Po ALW. Dictionary of evidence-based Medicine. Radcliffe Publishing, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mao HF, Hsueh IP, Tang PF et al. . Analysis and comparison of the psychometric properties of three balance measures for stroke patients. Stroke 2002;33:1022–7. 10.1161/01.STR.0000012516.63191.C5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munoz-Mendoza CL, Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Millán-Calenti JC et al. . Reliability of 4-m and 6-m walking speed tests in elderly people with cognitive impairment. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;52:e67–70. 10.1016/j.archger.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pitkälä K, Savikko N, Poysti M et al. . Efficacy of physical exercise intervention on mobility and physical functioning in older people with dementia: a systematic review. Exp Gerontol 2013;43:85–93. 10.1016/j.exger.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]