Abstract

Objectives

To examine the hypothesis that respondents with any of three specific sleep patterns would have a higher likelihood of suicidality than those without reports of these patterns in Korean adolescents.

Setting

Data from the 2011–2013 Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey were used.

Participants

191 642 subjects were included. The survey's target population was students in grades 7 through 12 in South Korea.

Independent variable

Sleep time.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts.

Results

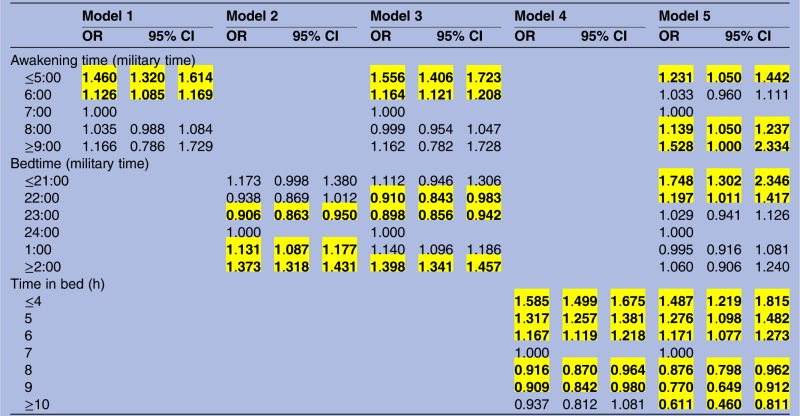

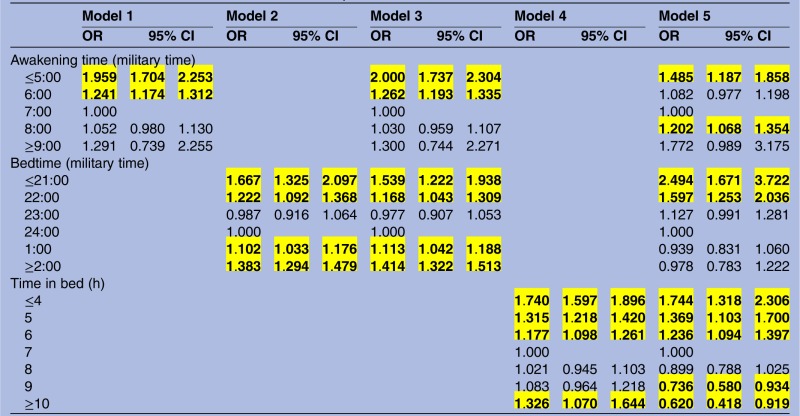

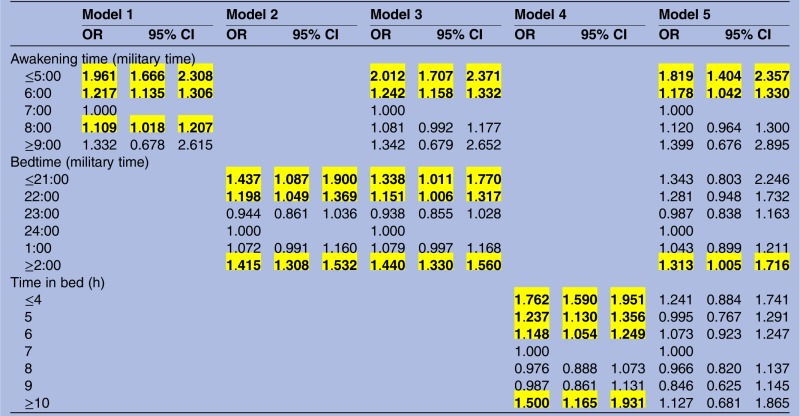

The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with very short or long time in bed were 1.487-fold higher (95% CI 1.219 to 1.815) or 0.611-fold lower (95% CI 0.460 to 0.811), respectively, than for subjects with 7 h/day in bed; the odds were similar for suicidal plans. The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with early or late awakening times were 1.231-fold higher (95% CI 1.050 to 1.442) or 1.528-fold lower (95% CI 1.000 to 2.334), respectively, than for subjects with 7 h/day in bed; these odds were lower for suicidal plans and attempts. The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with early bedtime were 1.748-fold higher (95% CI 1.302 to 2.346), the odds of suicidal plans in people with an early bedtime were 2.494-fold higher (95% CI 1.671 to 3.722) and the odds of suicide attempts in subjects with late bedtime were 1.313-fold higher (95% CI 1.005 to 1.716) than for subjects with a bedtime of 23:00.

Conclusions

The sleep-related time is associated with suicide-related behaviours in Korean adolescents. Multilateral approaches are needed to identify the greatest risk factors for suicidal behaviours.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, MENTAL HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used nationwide large representative 3-year aggregated survey data of adolescent students in grades 7 through 12. The large population sample size was representative of the overall population in grades 7 through 12, so these results can be generalised to the whole population of adolescents in grades 7 through 12 in South Korea.

Respondent reports are subjective and imperfect measures, potentially affected by perception bias and adaptation of resources.

We used representative data for our estimates, but the results possibly reflected reverse causality and bidirectional relationships when the associations between time in bed and suicidal behaviour patterns were assessed.

Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of death among children and adolescents in many countries.1 WHO estimated that suicide was the second highest cause of mortality in the 10–24-year age group and the rate continues to increase.

Suicidal behaviour includes suicidal thoughts, plans, attempts and death.2 3 Suicidal behaviours among adolescents are an emerging global public health problem and a socioeconomic burden. The highest prevalence of adolescent suicide is in Southeast Asia4 and Eastern Europe,5 and it is the second leading cause of death in the USA for teenagers aged 15–19 years.6

In South Korea, the overall rate of suicidal thoughts in young people aged 19–29 years was 15% in 2009 and the 1-year prevalence of suicidal thoughts was 2.6% in male subjects and 6.3% in female subjects aged between 18 and 29 years of age in 2011.7 The suicide rate among adolescents between 10 and 19 years of age is 5.2 per 100 000 people in South Korea and is the leading cause of death among adolescents in this country. Although the adolescent suicide rate was stable during the 1990s in some countries, suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among adolescents aged 15–19 years and continues to be a major burden on social healthcare systems in many countries8 as well as Korea.

Suicide attempts are a significant risk factor for subsequent death by suicide.9 The prevalence rate of attempted suicides among Korean adolescents between 13 and 18 years of age was reportedly 4.7%.3

Recent research has identified sleep problems as potentially important risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviours,10 and investigated the epidemiological phenomena and the risk factors associated with suicidal behaviour. Tang et al11 investigated 10 233 adolescent students in southern Taiwan and reported that variables including female gender, weekly alcohol use, illicit drug use, depression, significant family conflicts, poor family functioning, reduced interest in school, a low rank in school, low acceptance among peer groups and dropping out of school are associated with adolescent suicide attempts. Biological studies have indicated that considerable changes occur during adolescence, such as melatonin secretion and a need for a greater total time in bed, possibly owing to maturational changes in neuronal connectivity.12

In surveys of the general population, approximately one-third of adults reported one or more sleep complaints in the past year,13 and study shows that the associations between sleep disorder, such as insomnia, and suicidal behaviour are seen in clinically depressed and anxious populations.14 Insomnia was more strongly associated with suicidal thoughts than was poor-quality sleep15 16 and seemed to lead to an increased risk for suicidal thoughts, attempts and death by suicide.17

Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study, Roth et al18 determined that 16–25% of the adult population had had sleep problems lasting for ≥2 weeks in the past 12 months, 16.4% difficulty in falling sleep, 16.7% early morning awakening, 19.9% difficulty maintaining sleep and 25% non-restorative sleep.

Sleep problems are associated strongly with co-occurring psychiatric disorders,19 which in turn are associated with an increased risk of suicide. Individuals with sleep difficulties have a higher probability of symptoms or a diagnosis of depression, anxiety disorder or a substance abuse disorder than those without sleep complaints.20

Previous studies have shown that sleep problems and depression are potentially major factors for suicidal thoughts or attempts,21–23 particularly in adolescents.24 25 In Korea, although suicidal thoughts and attempts were associated with depression and alcohol abuse disorders in adults according to previous studies, the potential association between sleep problems and suicide in Korean adolescents remains unclear.

Therefore, in this study, we hypothesised that respondents with any of three specific sleep patterns would have a higher likelihood of suicidality than those without these patterns. Additionally, we hypothesised that sleep problems would be associated with greater risks of suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts during the preceding 12 months, even after controlling for other established risk factors for suicidality, such as socioeconomic status, disease status and psychiatric comorbidities.

Methods

Study sample and design

This study used data from the 2011–2013 Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS) conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDCP). The KYRBWS was a retrospective epidemiological study with a complex sample design that included multistage sampling, stratification and clustering, and has been conducted annually as an anonymous, online, self-reporting survey. The survey consists of 128 questions assessing demographic characteristics and 14 areas of health-related behaviours, including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, physical activity, eating habits, injury prevention, sexual behaviours, mental health, oral health, allergic disorders, personal hygiene, internet addiction, drug abuse and health equity. The survey's target population was students in grades 7 through 12 in South Korea. From each grade level, one sample class was chosen and all students from the six sample classes of each school were chosen as the sample students. We submitted a data request form on the KCDCP website and after an internal review by KCDCP and approval, we obtained the KYRBWS-VI survey data with all private information treated anonymously. During the survey, participants were assigned identification (ID) numbers and guaranteed anonymity. Teachers assigned a computer to each student randomly and provided the survey information. After the process had been explained, each student accessed the website using his or her ID number and completed the survey.

The survey was completed by a total of 75 643 of 79 202 students in 2011—a 95.5% participation rate, 74 186 of 76 980 students in 2012—a 96.4% participation rate and 72 435 of 75 149 students—a 96.4% participation rate.

Independent variables of main interest

Self-reported time in bed, awakening time and bedtime were assessed for each adolescent by asking, “What time did you usually go to bed and wake-up last week?” The responses for awakening time were categorised as ≤5:00, 6:00, 7:00, 8:00 and ≥9:00 and the responses for bedtime were categorised as ≤21:00, 22:00, 23:00, 24:00, 1:00 and ≥2;00; numbers represent the military time of day.

The time in bed was calculated based on reported sleep and awakening times and the responses were ≤4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and ≥10 h.

Dependent variables

Suicidal thought was investigated by asking the question, “Have you had suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months?” The responses were either “yes” or “no”.

Suicidal plan was investigated by asking the question, “Have you had suicidal plans in the past 12 months?” The responses were either “yes” or “no”.

A suicide attempt was investigated by asking the question, ‘Have you attempted suicide in the past 12 months?’ The responses were either “yes” or “no”.

Covariate variables

Socioeconomic variables

The age range of participants was 12–18 years (middle- and high-school students). Type of residence data were obtained from the students' address; the categories were metropolitan, urban and rural. Economic status was evaluated by asking the question, “What is your parents' economic status?” Responses were categorised as low, middle and high. Scholastic performance during the previous year was categorised as low, middle and high. Disease status included conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis.

Health risk and behavioural variables

Drug, smoking and alcohol use histories were evaluated for each participant by asking, “Have you ever used drugs such as gas?”, “Have you ever smoked more than one cigarette?” and “Have you ever consumed more than one glass of alcohol?”, respectively. Exercise was evaluated for each participant by asking, “In the last week, how many times did you exercise?” The responses were categorised as no exercise, 1–4 times a week and 5 times a week. The presence of depression was investigated by the question, “Have you ever experienced a deep sense of sadness or despair in the past 12 months?” The responses were either “yes” or “no”.

Analytical approach and statistics

In this study, five different models were tested. Model 1 tested the relationship between awakening time and suicide-related behaviours, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables. Model 2 tested the relationship between bedtime and suicide-related behaviours, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables. Model 3 tested the relationship among awakening time, bedtime and suicidal thoughts, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables. Model 4 tested the relationship between time in bed and suicidal thoughts, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables. Model 5 tested the relationship among awakening time, bedtime and duration and suicidal thoughts, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables.

To analyse whether general characteristics, health status and health risk behaviour were associated with suicidal thoughts, t tests, χ2 tests and multiple logistic regression analyses were used. For all analyses, a two-tailed p value ≤0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using the SAS statistical software package V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Prevalence of sleep problems

Table 1 lists the general characteristics of the covariates in this study, which included 191 642 participants. The weighted prevalence was 9.6% for very short sleep duration (≤4 h) and 1.0% for very long time in bed (≥10 h). The weighted prevalence was 1.5% for subjects with an early awakening time (≤5:00) and 0.1% for those with a late awakening time (≥9:00) (table 1). The weighted prevalence was 0.8% for subjects with an early bedtime (≤21:00) and 22.4% for those with a late bedtime (≥2:00). The weighted prevalences of suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts were 17.7%, 5.8% and 3.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Total |

Suicidal ideation |

No suicidal ideation |

Suicidal plan |

No suicidal plan |

Suicide attempt |

No suicide attempt |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %* | N | %* | N | %* | p Value† | N | %* | N | %* | p Value† | N | %* | N | %* | p Value† | |

| Awakening time (military time) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| ≤5:00 | 3048 | 1.5 | 829 | 27.2 | 2219 | 72.8 | 364 | 11.9 | 2684 | 88.1 | 258 | 8.2 | 2790 | 91.8 | |||

| 6:00 | 43 906 | 22.0 | 8700 | 19.7 | 35 206 | 80.3 | 2816 | 6.4 | 41 090 | 93.6 | 1830 | 4.1 | 42 076 | 95.9 | |||

| 7:00 | 121 261 | 63.7 | 20 556 | 16.8 | 100 705 | 83.2 | 6540 | 5.3 | 114 721 | 94.7 | 4232 | 3.4 | 117 029 | 96.6 | |||

| 8:00 | 23 199 | 12.6 | 4016 | 17.3 | 19 183 | 82.7 | 1465 | 6.3 | 21 734 | 93.7 | 979 | 4.1 | 22 220 | 95.9 | |||

| ≥9:00 | 228 | 0.1 | 48 | 20.9 | 180 | 79.1 | 19 | 8.2 | 209 | 91.8 | 13 | 5.5 | 215 | 94.5 | |||

| Bedtime (military time) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| ≤21:00 | 1798 | 0.8 | 311 | 18.1 | 1487 | 81.9 | 141 | 8.6 | 1657 | 91.4 | 85 | 5.2 | 1713 | 94.8 | |||

| 22:00 | 9980 | 4.6 | 1460 | 14.9 | 8520 | 85.1 | 603 | 6.3 | 9377 | 93.7 | 398 | 4.1 | 9582 | 95.9 | |||

| 23:00 | 33 472 | 16.4 | 4766 | 14.2 | 28 706 | 85.8 | 1667 | 5.0 | 31 805 | 95.0 | 1024 | 3.1 | 32 448 | 96.9 | |||

| 24:00 | 56 028 | 29.2 | 9082 | 15.9 | 46 946 | 84.1 | 2948 | 5.1 | 53 080 | 94.9 | 1956 | 3.3 | 54 072 | 96.7 | |||

| 1:00 | 49 521 | 26.6 | 9006 | 17.9 | 40 515 | 82.1 | 3096 | 7.4 | 37 747 | 92.6 | 1763 | 3.4 | 47 758 | 96.6 | |||

| ≥2:00 | 40 843 | 22.4 | 9524 | 22.9 | 31 319 | 77.1 | 2749 | 5.4 | 46 772 | 94.6 | 2086 | 5.0 | 38 757 | 95.0 | |||

| Time in bed (h) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| ≤4 | 17 653 | 9.6 | 4610 | 25.6 | 13 043 | 74.4 | 1613 | 8.8 | 16 040 | 91.2 | 1114 | 6.1 | 16 539 | 93.9 | |||

| 5 | 34 078 | 18.3 | 6992 | 20.2 | 27 086 | 79.8 | 2104 | 6.1 | 31 974 | 93.9 | 1331 | 3.8 | 32 747 | 96.2 | |||

| 6 | 46 513 | 24.7 | 8450 | 17.8 | 38 063 | 82.2 | 2629 | 5.5 | 43 884 | 94.5 | 1718 | 3.6 | 44 795 | 96.4 | |||

| 7 | 47 892 | 24.8 | 7706 | 15.9 | 40 186 | 84.1 | 2485 | 5.1 | 45 407 | 94.9 | 1660 | 3.4 | 46 232 | 96.6 | |||

| 8 | 32 423 | 16.3 | 4595 | 14.1 | 27 828 | 85.9 | 1635 | 5.1 | 30 788 | 94.9 | 1025 | 3.2 | 31 398 | 96.8 | |||

| 9 | 10 984 | 5.3 | 1497 | 13.7 | 9487 | 86.3 | 599 | 5.4 | 10 385 | 94.6 | 370 | 3.2 | 10 614 | 96.8 | |||

| ≥10 | 2099 | 1.0 | 299 | 14.8 | 1800 | 85.2 | 139 | 6.9 | 1960 | 93.1 | 94 | 5.1 | 2005 | 94.9 | |||

| Grade | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| 13 | 30 904 | 15.4 | 5340 | 17.6 | 25 564 | 82.4 | 2078 | 6.9 | 28 826 | 93.1 | 1386 | 4.5 | 29 518 | 95.5 | |||

| 14 | 31 201 | 15.8 | 5864 | 18.7 | 25 337 | 81.3 | 2229 | 7.1 | 28 972 | 92.9 | 1508 | 4.9 | 29 693 | 95.1 | |||

| 15 | 31 992 | 16.6 | 5834 | 18.2 | 26 158 | 81.8 | 2056 | 6.5 | 29 936 | 93.5 | 1362 | 4.2 | 30 630 | 95.8 | |||

| 16 | 32 420 | 17.4 | 5803 | 17.6 | 26 617 | 82.4 | 1755 | 5.3 | 30 665 | 94.7 | 1163 | 3.5 | 31 257 | 96.5 | |||

| 17 | 32 540 | 17.3 | 5924 | 17.7 | 26 616 | 82.3 | 1695 | 5.0 | 30 845 | 95.0 | 1050 | 3.0 | 31 490 | 97.0 | |||

| 18 | 32 585 | 17.5 | 5384 | 16.3 | 27 201 | 83.7 | 1391 | 4.2 | 31 194 | 95.8 | 843 | 2.5 | 31 742 | 97.5 | |||

| Gender | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 95 800 | 51.8 | 12 955 | 13.6 | 82 845 | 86.4 | 4400 | 4.6 | 91 400 | 95.4 | 2408 | 2.5 | 93 392 | 97.5 | |||

| Female | 95 842 | 48.2 | 21 194 | 22.1 | 74 648 | 77.9 | 6804 | 7.1 | 89 038 | 93.0 | 4904 | 5.1 | 90 938 | 94.9 | |||

| Region | 0.2686 | <0.0001 | 0.1894 | ||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 87 318 | 44.7 | 15 686 | 17.9 | 71 632 | 82.1 | 5130 | 5.8 | 82 188 | 94.2 | 3257 | 3.7 | 84 061 | 96.3 | |||

| Urban | 81 286 | 49.0 | 14 394 | 17.5 | 66 892 | 82.5 | 4674 | 5.7 | 76 612 | 94.3 | 3119 | 3.8 | 78 167 | 96.2 | |||

| Rural | 23 038 | 6.3 | 4069 | 17.6 | 18 969 | 82.4 | 1400 | 6.0 | 21 638 | 94.0 | 936 | 4.0 | 22 102 | 96.0 | |||

| Economic status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||||

| Low | 42 507 | 21.6 | 10 464 | 24.4 | 32 043 | 75.6 | <0.0001 | 2393 | 5.5 | 40 114 | 94.5 | ||||||

| Middle | 91 299 | 47.3 | 14 643 | 15.9 | 76 656 | 84.1 | 3496 | 8.1 | 39 011 | 91.9 | 2949 | 3.2 | 88 350 | 96.8 | |||

| High | 57 836 | 31.1 | 9042 | 15.7 | 48 794 | 84.3 | 4571 | 4.9 | 86 728 | 95.1 | 1970 | 3.4 | 55 866 | 96.6 | |||

| Academic performance | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Low | 71 076 | 36.9 | 15 260 | 21.4 | 55 816 | 78.6 | 5259 | 7.3 | 65 817 | 92.7 | 3738 | 5.1 | 67 338 | 94.9 | |||

| Middle | 52 533 | 27.5 | 8350 | 15.7 | 44 183 | 84.3 | 2540 | 4.7 | 49 993 | 95.3 | 1591 | 2.9 | 50 942 | 97.1 | |||

| High | 68 033 | 35.6 | 10 539 | 15.3 | 57 494 | 84.7 | 3405 | 5.0 | 64 628 | 95.0 | 1983 | 2.9 | 66 050 | 97.1 | |||

| Disease | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 36 232 | 19.5 | 7773 | 21.1 | 28 459 | 78.9 | 2758 | 7.5 | 33 474 | 92.5 | 1805 | 4.9 | 34 427 | 95.1 | |||

| No | 155 410 | 80.5 | 26 376 | 16.8 | 129 034 | 83.2 | 8446 | 5.3 | 146 964 | 94.7 | 5507 | 3.5 | 149 903 | 96.5 | |||

| Alcohol use | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 90 979 | 47.2 | 20 200 | 21.9 | 70 779 | 78.1 | 6943 | 7.5 | 84 036 | 92.5 | 4744 | 5.1 | 86 235 | 94.9 | |||

| No | 100 663 | 52.8 | 13 949 | 13.9 | 86 714 | 86.1 | 4261 | 4.2 | 96 402 | 95.8 | 2568 | 2.5 | 98 095 | 97.5 | |||

| Smoking use | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 45 203 | 23.5 | 11 271 | 24.3 | 33 932 | 75.7 | 4318 | 9.3 | 40 885 | 90.7 | 3124 | 6.7 | 42 079 | 93.3 | |||

| No | 146 439 | 76.5 | 22 878 | 15.6 | 123 561 | 84.4 | 6886 | 4.7 | 139 553 | 95.3 | 4188 | 2.8 | 142 251 | 97.2 | |||

| Drug use | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1811 | 0.9 | 836 | 45.5 | 975 | 54.5 | 542 | 29.1 | 1269 | 70.9 | 400 | 21.1 | 1411 | 78.9 | |||

| No | 189 831 | 99.1 | 33 313 | 17.4 | 156 518 | 82.6 | 10 662 | 5.5 | 179 169 | 94.5 | 6912 | 3.6 | 182 919 | 96.4 | |||

| Exercise | <0.0001 | 0.0372 | 0.0674 | ||||||||||||||

| No | 52 047 | 27.1 | 9973 | 18.9 | 42 074 | 81.1 | 3079 | 5.8 | 48 968 | 94.2 | 2003 | 3.8 | 50 044 | 96.2 | |||

| 1–4 Times a week | 114 725 | 60.0 | 20 050 | 17.4 | 94 675 | 82.6 | 6604 | 5.7 | 108 121 | 94.3 | 4307 | 3.7 | 110 418 | 96.3 | |||

| 5 Times a week | 24 870 | 12.9 | 4126 | 16.6 | 20 744 | 83.4 | 1521 | 6.1 | 23 349 | 93.9 | 1002 | 4.0 | 23 868 | 96.0 | |||

| Depressive symptoms | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 59 858 | 30.9 | 24 511 | 40.9 | 35 347 | 59.1 | 8495 | 14.1 | 51 363 | 85.9 | 5775 | 9.5 | 54 083 | 90.5 | |||

| No | 131 784 | 69.1 | 9638 | 7.3 | 122 146 | 92.7 | 2709 | 2.0 | 129 075 | 98.0 | 1537 | 1.2 | 130 247 | 98.8 | |||

| Year | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.3321 | ||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 64 647 | 33.7 | 12 381 | 19.1 | 52 266 | 80.9 | 4047 | 6.2 | 60 600 | 93.8 | 2551 | 3.8 | 62 096 | 96.2 | |||

| 2012 | 63 688 | 33.1 | 11 431 | 17.7 | 52 257 | 82.3 | 3754 | 5.8 | 59 934 | 94.2 | 2329 | 3.6 | 61 359 | 96.4 | |||

| 2013 | 63 307 | 33.2 | 10 337 | 16.2 | 52 970 | 83.8 | 3403 | 5.3 | 59 904 | 94.7 | 2432 | 3.8 | 60 875 | 96.2 | |||

| Total | 191 642 | 100.0 | 34 149 | 17.7 | 157 493 | 82.3 | 11 204 | 5.8 | 180 438 | 94.2 | 7312 | 3.7 | 184 330 | 96.3 | |||

*weighted %; †weighted p value.

Association between sleep problems and suicide-related behaviours

Association between sleep problems and suicidal thoughts

Table 2 shows the association between variables and suicidal thoughts. In model 5, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables, the odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with a very short time in bed was 1.487-fold higher (95% CI 1.219 to 1.815) than for those with 7 h/day in bed. The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with a very long time in bed were 0.611-fold lower (95% CI 0.460 to 0.811) than for those with 7 h/day in bed. The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with an early awakening time was 1.231-fold higher (95% CI 1.050 to 1.442) than in those with 7 h/day in bed. The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with a late awakening time were 1.528-fold lower (95% CI 1.000 to 2.334) than in those with 7 h/day in bed.

Table 2.

Association between variables and suicidal ideation

|

Adjusted for grade, gender, region, economic status, academic performance, disease, alcohol use, smoking use, drug use, exercise, depressive symptoms and year.

The odds of suicidal thoughts in subjects with an early bedtime was 1.748-fold higher (95% CI 1.302 to 2.346) than in those with a bedtime of 24:00.

Association between sleep problems and suicidal plan

Table 3 shows the association between variables and suicidal plans. In model 5, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables, the odds of suicidal plans in subjects with a very short time in bed were 1.744-fold higher (95% CI 1.318 to 2.306) than in those with a time in bed of 7 h/day. The odds of suicidal plans in subjects with a very long time in bed were 0.620-fold lower (95% CI 0.418 to 0.919) than in those with 7 h/day in bed. The odds of suicidal plans in subjects with an early awakening time were 1.485-fold higher (95% CI 1.187 to 1.858) than in those with a wakening time of 7:00. The odds of suicidal plans in subjects with an early bedtime was 2.494-fold higher (95% CI 1.671 to 3.722) than in those with a bedtime of 24:00.

Table 3.

Association between variables and suicidal plan

|

Adjusted for grade, gender, region, economic status, academic performance, disease, alcohol use, smoking use, drug use, exercise, depressive symptoms and year.

Association between sleep problems and suicide attempt

Table 4 shows the associations between variables and suicide attempts. In model 5, adjusted for socioeconomic, health risk and behavioural variables, the odds of suicide attempts in subjects with an early awakening time were 1.819-fold higher (95% CI 1.404 to 2.357) than in those with a wakening time of 7:00. The odds of suicide attempts in subjects with a late bedtime were 1.313-fold higher (95% CI 1.005 to 1.716) than in those with a bedtime of 23:00.

Table 4.

Associations between variables and suicide attempt

|

Adjusted for grade, gender, region, economic status, academic performance, disease, alcohol use, smoking use, drug use, exercise, depressive symptoms and year.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between sleep problems (awakening time, bedtime and time in bed) and suicide-related behaviours among Korean adolescents using a nationally representative sample. Because the likely association between sleep problems and suicide-related behaviours depends on different processes in adolescents than in adults, conducting additional studies to verify this association in adolescents is important.

Overall, in this study, sleep problems tended to be associated with suicide-related behaviours and awakening time and bedtime patterns were U-shaped, similar to our previous study in Korean adults.26

In order to detect the existence and multicollinearity between time in bed, awakening time and bedtime in our analysis model, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to assess the extent to which the variances of the estimated coefficients were inflated. A predictor with VIF>10 is considered to be indicative of serious multicollinearity.27 We examined the VIF in the regression coefficients of all variables, including time in bed, awakening time and bedtime for 0<VIF<3. Suicide attempts among subjects with early awakening times showed a greater effect than did suicide thoughts and suicide plans (model 5). Suicide plans in subjects with early bedtime showed a greater effect than did suicidal thoughts, and a late bedtime (≥2:00) was associated with a high probability of suicide attempts (model 5). However, unlike in our previous study,26 the correlation of time in bed with suicide-related behaviours was not U-shaped, and although suicide attempts were not associated with time in bed after adjusting for awakening time and bedtime, subjects with extreme time in bed showed decreased suicidal thoughts and suicidal plans.

Sleep loss can cause various psychological and physiological impairments, with endocrine and immunological changes.28 Although the association between inappropriate sleep patterns and suicidal behaviours requires plausible physiological mechanisms for such a cause-and-effect relationship, several researchers have proposed that inhibition of the serotonin (5-hydroxytriptamine) system plays a significant role in both suicide and sleep.29

These associations were independent of sociodemographic variables (age, gender, region and economic status), health risk behaviour variables (alcohol, smoking and drug use history and exercise), health status (depressive symptoms and disease), academic performance and the year.

Adequate sleep is essential for good health and optimal physical and cognitive performance.30

However sleep problems in adolescents are common and sleep disruption is associated with a wide range of behavioural, cognitive and mood impairments in adolescents.31

Many clinical studies in adolescents have consistently reported that reduced hours of sleep are associated with emotional problems such as depression and anxiety,16 17 in addition to self-harm and suicidal thoughts.22 Poor sleep has also been correlated with increased aggression, irritability and hostility in both adults and adolescents, conducive to problems and bullying behaviour in school children and habitual substance misuse, self-injurious behaviours and suicide attempts overall.32

This study has a number of clinical implications for adolescents in Korea.33 34 First, a comprehensive evaluation of suicide behaviours should include a sleep time assessment, irrespective of whether or not an individual reports other medical conditions including mental disorder, and continual screening and treatment are necessary. Second, sleep problems should alert treatment providers to a possible high risk of suicide. Finally, the causes of the unique patterns and the high prevalence of suicidal behaviours in Korean adolescents are unclear, which suggests that multidisciplinary efforts and studies, including psychiatric, familial and social aspects, are urgently required to solve the problem. Future research is needed.

This study had several strengths and limitations. One strength was that the participants in the survey were representative of the overall adolescent student population attending in grades 7 through 12. Additionally, the number of participants was large; therefore the results can be generalised to the overall adolescent population in South Korea.

Nevertheless, limitations in sample bias existed. First, all data collected were derived from a self-reported questionnaire, including the individual mean number of sleep hours, suicide-related behaviours, stress-related factors and drug use, which might have affected the results; however, all participants were informed that their responses would remain anonymous. In addition, self-evaluation tools may be affected by cognitive biases, including recall bias, erroneous self-perception, as well as the desire to please, displease or provoke, particularly in adolescents. Second, disadvantages of web-based surveys should be considered, including the lack of access to clinical information and the fact that not all participants were equally computer literate. Third, since data on various mental disorders or the general mental health of the study participants were not available, controlling for their possible contribution was difficult. Although results of various studies15 35 36 investigating the insomnia–suicide risk link and the psychological mechanisms underpinning the association were observed, insomnia variable was not included for analysis because of lack of information. Therefore, future studies should refine our understanding through more in-depth studies. Finally, owing to the cross-sectional nature of this study, determining a causal relationship between coping behaviour and suicidal thoughts was not possible and future studies using a longitudinal design are needed to evaluate this relationship.

Conclusion

The findings of our large, representative, population-based study indicate an association between sleep problems and suicide-related behaviours among adolescents in South Korea. Based on the results of this study, we conclude that multilateral strategies for adolescents would be helpful in dealing with the risks of suicidality, and improved strategies are needed to identify subjects at greatest risk of suicidal behaviour.

Acknowledgments

We thank Textcheck for checking and correcting the English in our manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: J-HK, SGL, E-CP designed the study, researched the data, performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. J-HK, K-BY contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. K-BY is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Pompili MIM, Vichi M, Masocco M et al. Suicide prevention among youths. Systematic review of available evidence-based interventions and implications for Italy. Minerva Pediatr 2010;62:507–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin RD, Marusic A. Association between short sleep and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adults in the general population. Sleep 2008;31:1097–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bursztein C, Apter A. Adolescent suicide. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009;22:1–6. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283155508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varnik P. Suicide in the world. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:760–71. 10.3390/ijerph9030760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Mortality of Russian teenagers from suicide. Moscow: UNICEF, Russian Federation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCfIPaC. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars

- 7.Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. The epidemiological survey of mental disorders in Korea. Seoul: Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Suicidal ideation and associated factors among school-going adolescents in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:462–73. 10.3390/ijerph9020462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Aalst JA, Shotts SD, Vitsky JL et al. Long-term follow-up of unsuccessful violent suicide attempts: risk factors for subsequent attempts. J Trauma 1992;33:457–64. 10.1097/00005373-199209000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:84–91. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang TC, Ko CH, Yen JY et al. Suicide and its association with individual, family, peer and school factors in an adolescent population in southern Taiwan. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2009;39:91–102. 10.1521/suli.2009.39.1.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colrain IM, Baker FC. Changes in sleep as a function of adolescent development. Neuropsychol Rev 2011;21:5–21. 10.1007/s11065-010-9155-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartz AJ, Daly JM, Kohatsu ND et al. Risk factors for insomnia in a rural population. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:940–7. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winsper C, Tang NKY. Linkages between insomnia and suicidality: prospective associations, high-risk subgroups and possible psychological mechanisms. Int Rev Psychiatry 2014;26:189–204. 10.3109/09540261.2014.881330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woosley JA, Lichstein KL, Taylor DJ et al. Insomnia complaint versus sleep diary parameters: predictions of suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2015. 10.1111/sltb.12173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cukrowicz KCOA, Pinto JV, Bernert RA et al. The impact of insomnia and sleep disturbances on depression and suicidality. Dreaming 2006;16:1–10. 10.1037/1053-0797.16.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernert RAJT, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB et al. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep 2005;28:1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth T, Jaeger S, Jin R et al. Sleep problems, comorbid mental disorders and role functioning in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 2006;60:1364–71. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L et al. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry 1996;39:411–18. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Robinson EA et al. Insomnia, self-medication and relapse to alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:399–404. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takada M, Suzuki A, Shima S et al. Associations between lifestyle factors, working environment, depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation: a large-scale study in Japan. Ind Health 2009;47:649–55. 10.2486/indhealth.47.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YJ, Cho SJ, Cho IH et al. Insufficient sleep and suicidality in adolescents. Sleep 2012;35:455–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM et al. Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J Affect Disord 2012;136:743–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCall WV, Blocker JN, D'Agostino R et al. Insomnia severity is an indicator of suicidal ideation during a depression clinical trial. Sleep Med 2010;11:822–7. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong MM, Brower KJ, Zucker RA. Sleep problems, suicidal ideation and self-harm behaviors in adolescence. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:505–11. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JH, Park EC, Cho WH et al. Association between total sleep duration and suicidal ideation among the Korean general adult population. Sleep 2013;36:1563–72. 10.5665/sleep.3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan MY, Frost SA, Center JR et al. Relationship between body mass index and fracture risk is mediated by bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:2327–35. 10.1002/jbmr.2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet 1999;354:1435–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohyama J. Sleep, serotonin and suicide in Japan. J Physiol Anthropol 2011;30:1–8. 10.2114/jpa2.30.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikeos D, Georgantopoulos G. Medical comorbidity of sleep disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2011;24:346–54. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283473375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Brien LM. The neurocognitive effects of sleep disruption in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2009;18:813–23. 10.1016/j.chc.2009.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahl RE, Puig-Antich J, Ryan ND et al. EEG sleep in adolescents with major depression: the role of suicidality and inpatient status. J Affect Disord 1990;19:63–75. 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojnar M, Ilgen MA, Wojnar J et al. Sleep problems and suicidality in the national comorbidity survey replication. J Psychiatr Res 2009;43:526–31. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang EH, Hyun MK, Choi SM et al. Twelve-month prevalence and predictors of self-reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among Korean adolescents in a web-based nationwide survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:47–53. 10.1177/0004867414540752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernert RA, Nadorff MR. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk. Sleep Med Clin 2015;10:35–9. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pigeon WRBP, Ilgen MA, Chapman B et al. Sleep disturbance preceding suicide among veterans. Am J Public Health 2012;102:S93–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]