Abstract

Therapies targeting estrogen receptor α (ERα) including selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), e.g., tamoxifen; selective estrogen receptor downregulators (SERDs), i.e., fulvestrant (ICI 182,780); and aromatase inhibitors (AI), e.g., letrozole, are successfully used in treating breast cancer patients whose initial tumor expresses ERα. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of endocrine therapies is limited by acquired resistance. The role of miRNAs in the progression of endocrine-resistant breast cancer is of keen interest in developing biomarkers and therapies to counter metastatic disease. This review focuses on miRNAs implicated as disruptors of antiestrogen therapies, their bona fide gene targets, and associated pathways promoting endocrine resistance.

Keywords: Antiestrogen, aromatase inhibitor, breast cancer, endocrine-resistance, estrogen receptor, miRNA, tamoxifen

Introduction

The sustained exposure to endogenous estrogens is involved in the initiation and progression of breast cancer (Colditz 1998). The cellular effects of estrogens are mediated by estrogen receptor α and β (ERα and ERβ) and their splice variants (Herynk and Fuqua 2004). Approximately 70% of primary breast tumors express ERα (Clark, et al. 1984; Ring and Dowsett 2004), providing the rationale for the successful use of targeted endocrine therapies in breast cancer progression (Reviewed in (Jordan, et al. 2014)).

Endocrine therapies including selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) e.g., tamoxifen (TAM); serum estrogen down regulators (SERDs), e.g., fulvestrant (ICI 182,780) and aromatase (CYP19A) inhibitors (AI), e.g., anastrozole and letrozole, are the frontline adjuvant therapies in treatment of women with ERα positive breast tumors (Regan, et al. 2011). These therapies have resulted in substantial improvements in outcomes and quality of lives of breast cancer survivors (Jordan, et al. 2011). Adjuvant TAM therapy with TAM was the mainstay for ERα positive(+) breast cancer management until clinical trials comparing TAM with AIs which block the conversion of androgens to estrogens (Santen, et al. 2009), were proven to provide a significant increase in disease-free survival (Cuzick, et al. 2010; Regan et al. 2011). Unfortunately, the effectiveness of TAM and AI therapy is limited as seen in relapse of ~ 40% of patients (1998). When resistance occurs, it is unclear which subsequent endocrine therapy is most appropriate (Choi, et al. 2015). Fulvestant is used as second-line therapy for patients with metastatic breast cancer, after developing AI- or TAM- resistance (Johnston, et al. 2005; Perey, et al. 2007). Endocrine resistance can be intrinsic (de novo) or acquired (reviewed in (Clarke, et al. 2003)). In intrinsic resistance, patients are initially unresponsive to endocrine therapies due to lack of ERα while in acquired resistance, patients become unresponsive after the initial 5 year treatment, even though ERα is still expressed (Dowsett, et al. 2010). Biological mechanisms underlying de novo and acquired resistance are therefore of considerable clinical significance. Overall, the mechanisms of endocrine resistance are many and include amplification of multiple growth signaling pathways (Bedard, et al. 2008; O’Brien, et al. 2009; Palmieri, et al. 2014; Riggins, et al. 2005; Ring and Dowsett 2004). Recently, ERα ligand binding domain (LBD) mutants that are intrinsically active in the absence of ligand were identified in AI-resistant metastatic disease, but not TAM-resistant metastases (Li, et al. 2013b; Robinson, et al. 2013; Toy, et al. 2013), providing a new impetus for understanding ERα’s role in driving metastatic disease (Jordan, et al. 2015). This review will focus on the role of miRNAs in acquired endocrine resistant breast cancer.

MicroRNA (miRNAs or miRs) are small (22 nt), non-protein coding RNAs first identified over a decade ago (Iorio and Croce 2012). Their dysregulation has been implicated in many diseases, including breast cancer (Iorio and Croce 2012). Post-transcriptionally, miRNAs regulate the expression of target genes and are novel candidates for clinical development as therapeutic targets and biomarkers. The role of noncoding RNAs and miRNAs in breast cancer and endocrine resistant breast cancers have been recently reviewed (Hayes and Lewis-Wambi 2015; van Schooneveld, et al. 2015). Here we will review studies demonstrating dysregulation of miRNAs linked to endocrine resistance that result in breast cancer progression. We also describe the bone fide targets of these miRNAs and the molecular pathways dysregulated in conferring resistance. We will summarize miRNAs with predictive and prognostic potential in endocrine-resistant breast cancer.

Overview of ER pathways in breast tumors

The biological effects of estrogens, including E2, are mediated by binding to nuclear receptors ERα and ERβ and their splice variants, e.g., ERα36 and ERα46, and G-protein coupled ER (GPER). The ERα activation initiated by E2 binding and consequent conformational changes results in “nuclear/genomic” or “non-genomic/membrane-initiated” responses (Levin 2014; Watson, et al. 2012). ERα is upregulated in breast tumors (Clark and McGuire 1988). It is the target for therapeutic agents originally termed antiestrogens because they compete with E2 for ERα binding, but now termed SERMs and SERDs because of our greater understanding of their molecular actions (Jordan et al. 2014). Because the role of ERβ in breast cancer remains to be clearly established (reviewed in (Thomas and Gustafsson 2011)) and because ERα expression is higher than ERβ in breast tumors and is thus the target of therapeutic intervention, this review will focus primarily on ERα activities related to miRNA expression and activity in endocrine-resistance.

In the non-nuclear/membrane-initiated ER pathways, E2 rapidly alters intracellular signaling pathways culminating in changes in gene transcription by a processes mediated by plasma membrane-associated ERα, ERβ, or GPER/GPR30 (reviewed in (Arpino, et al. 2008; Filardo, et al. 2008; Levin 2014; Riggins et al. 2005; Watson et al. 2012)). These rapid responses include E2 activation of PI3K and Src in the plasma membrane (PM) which then activate mTOR through PI3K-mediated AKT phosphorylation. Membrane ER and GPER activate epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) with downstream signaling through Ras/Raf and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Razandi, et al. 2003). E2 activation of EGFR can increase ERα phosphorylation (reviewed in (Arpino et al. 2008; Johnston 2010; Renoir, et al. 2013)). These signaling pathways subsequently regulate ER transcriptional activity. Despite the numerous studies on ERα, the events and overall processes including their regulated gene targets are not completely understood.

Mechanisms of endocrine therapy in breast cancer

Antiestrogen therapies function by two main mechanisms: targeting ERα activity and/or stability. SERMs, e.g., TAM, raloxifene (RAL), and toremifene, compete with E2 for binding the LBD of ERα and inhibit ERα transcriptional activity in a gene- and cell-specific manner. SERMs can be agonists or antagonists depending on the tissue and gene. For example, SERMs are agonists for ERα in the endometrium and increase endometrial tumor incidence (Fornander, et al. 1989; Gottardis, et al. 1988). As antagonist, SERMs are used in the treatment of breast cancer patients with ERα+ breast tumors (Baum, et al. 1983). SERDs, i.e., fulvestrant (ICI 182,780, Faslodex), not only alters the ERα conformation, but stimulate ER protein degradation (Jordan and Brodie 2007; Osborne and Schiff 2011; Zhao and Ramaswamy 2014). AIs inhibit the activity of aromatase (CYP19A1), thus reducing estrogen synthesis in peripheral adipose tissues and within tumor (Zhao and Ramaswamy 2014). Examples of AIs include letrozole and anastrozole, which are steroidal/irreversible inhibitors, and exemestane, a non-steroidal/reversible inhibitor (Zhao and Ramaswamy 2014).

For postmenopausal women with ERα+ primary tumors, ASCO guidelines recommend AI therapy and for premenopausal women TAM for 10 years is recommended (Smith 2014). Adjuvant therapy with TAM for postmenopausal women with endocrine responsive breast tumors effectively reduced the odds of recurrence by 40% and death from breast cancer after 5 years by 20% (1998). Unfortunately, 40–50% of patients initially responsive to TAM develop TAM resistance (Ring and Dowsett 2004). Likewise, a similar proportion of patients develop AI-resistance (Hayashi and Kimura 2015; Johnston et al. 2005). This indicates additional mechanisms evolve to promote breast cancer progression in the absence of estrogen signaling.

Overview of mechanisms of endocrine resistance

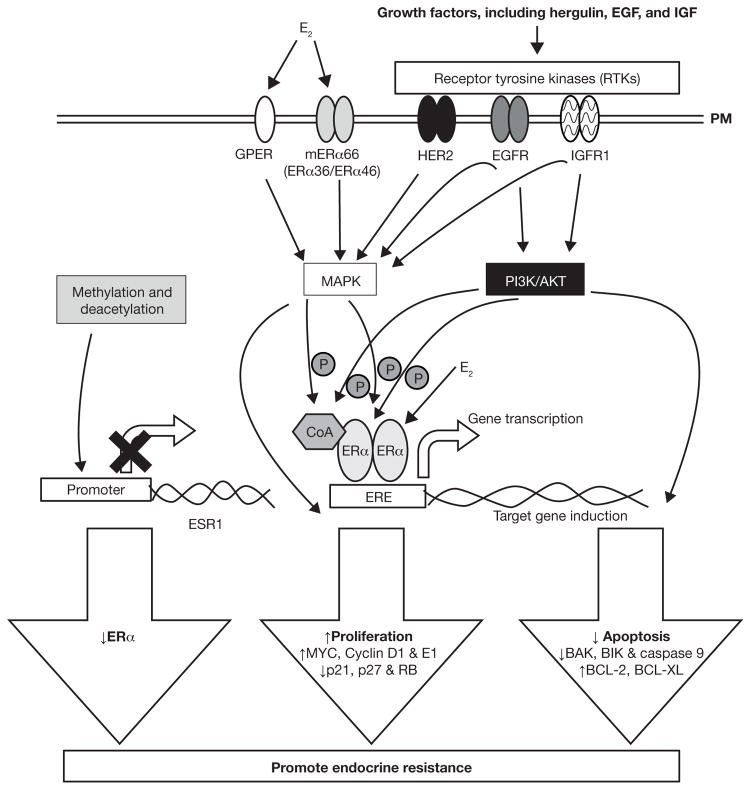

A number of molecular mechanisms have been implicated in promoting endocrine resistance (Figure 1) (Musgrove and Sutherland 2009; Nagaraj and Ma 2015; Ring and Dowsett 2004). For example, ERα expression is silenced by methylation, resulting in reduced ERα (Martinez-Galan, et al. 2014). Mutations in ERα (Herynk and Fuqua 2004) or increased expression of truncated forms of ERα, including ERα36 (Deng, et al. 2014), are potential mechanisms in acquired resistance. Alterations in ERα coregulators, e.g., increased expression of AP1 and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) are associated with endocrine resistance (Johnston, et al. 1999; Zhou, et al. 2007). Crosstalk between ERα and amplification or activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including EGFR and insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR), have been implicated in endocrine resistance (Arpino et al. 2008). Overexpression of HER2 (ERBB2) can elicit TAM resistance (Arpino et al. 2008), although HER2+ tumors are of a distinct molecular genotype from luminal A/ERα + breast tumors (Sorlie, et al. 2001). Apoptotic and cell survival signals are also dysregulated in TAM-resistant cells (Riggins et al. 2005). A more extensive review of mechanisms promoting endocrine resistance can be found in (Hasson, et al. 2013; Musgrove and Sutherland 2009; Zhao and Ramaswamy 2014). Additional factors are continually identified as playing roles in endocrine resistance.

Figure 1. Summary of the molecular mechanisms promoting acquired endocrine resistance.

Activation and or amplification of receptor RTKs including insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and HER2 have been detected in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells and endocrine-resistant patient tumors. Plasma membrane-associated GPER and ERα, including splice variants ERα36 ERα46, are increased in endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells and tumors. Activation of these receptors activate intracellular signaling cascades including MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways that ultimately increase transcription of genes that promote growth and survival and resistance to apoptosis. Additionally, these pathways increase ligand-independent ERα activation by phosphorylation. Alternatively, MAPK and PI3K/AKT can directly promote expression of non-ERE responsive genes by activating other transcription factors, e.g., AP-1, not shown here. Promoter methylation of CpG islands and histone deacetylation has been shown to repress ERα expression and promote endocrine resistance. Abbreviations: Estrogen receptor α (ERα), estrogen response element (ERE), G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), plasma membrane (PM), retinoblastoma (RB), V-Myc Avian Myelocytomatosis Viral (MYC), B-cell lymphoma (BCL), homologous antagonist killer (BAK), BCL-2-interacting killer (BIK)

miRNA biogenesis

miRNAs are evolutionarily conserved, small, non-coding, 22 nt RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of mRNAs to repress transcription or promote degradation (Iorio and Croce 2012). There are an estimated 2,588 miRNAs arising from intragenic or intergenic regions of the human genome (June 2014; http://www.mirbase.org/) (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones 2014). Intragenic, i.e., intronic or exonic, miRNAs, which constitute about half of all miRNAs (Berillo, et al. 2013), originate from within protein coding genes and can therefore have a shared promoter (and/or transcriptional start site (TSS)) and are expressed simultaneously with their host protein-coding transcript (Baskerville and Bartel 2005; Rodriguez, et al. 2004). However, later findings suggest this may not be the case and regulation of intronic miRNA transcription can occur independent from the host gene (Gennarino, et al. 2009; Marsico, et al. 2013). Intergenic miRNAs tend to have their own promoters (Gennarino et al. 2009). Determining these TSSs will be essential in understanding the regulation of miRNA expression. Sixty percent of all human protein coding genes are regulated by miRNAs (Friedman, et al. 2009) and because miRNAs regulate multiple mRNAs, they are implicated as key regulators in a variety of cellular processes including cell differentiation, cell death development, proliferation, and metabolism (Bartel 2004).

miRNA biogenesis occurs through canonical and non-canonical pathways. In the canonical pathway of miRNA biogenesis, the primary RNA transcript (pri-miRNA) is transcribed from DNA by RNA polymerase II. Pri-miRNA is further processed to a hairpin precursor transcript (Pre-miRNA; ~70 nt) by a microprocessor complex comprised of Drosha (RNase III enzyme) and associated DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (DGR8) (Han, et al. 2004). DGR8 anchors and recognizes the miRNA region for endonuclease cleavage by Drosha (Fukunaga, et al. 2012; Kim, et al. 2009). The Drosha microprocessor complex is also implicated in miRNA-independent functions including regulation of heteronuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) and alternative splicing (Macias, et al. 2013). Pre-miRNA is exported from the nucleus by Exportin 5 (a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein (Bohnsack, et al. 2004)) to the cytoplasm where it is further processed by another RNase III enzyme, DICER, in conjugation with trans-activation response (TAR) RNA binding protein (TRBP) and protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase (PACT; also known as PRKRA) results in a small dsRNA duplex (~22 nt) (Chendrimada, et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2009). One of the duplex strands is included in the RNA-induced silencing (RISC) complex where it recognizes and binds mRNA resulting in mRNA degradation or translational repression depending on the extent of complementarity (Huntzinger and Izaurralde 2011). The core RISC complex is composed of four Argonaute (Ago) proteins with AGO2 endonuclease activated upon recruitment of target mRNAs (Meister, et al. 2004).

In the non-canonical pathway, miRNAs (miRtrons) are processed by spliceosomes in an RNase III (Drosha)-independent manner (reviewed in (Yang and Lai 2011)). The intermediate generated is further processed by lariat debranching enzyme resulting in products that appear as pre-miRNA mimics. These mimics then enter the canonical pathway as Exportin 5 or DICER substrates.

miRNAs are considered to be key players in cellular transformation and in the initiation and progression of cancer (Wiemer 2007). Selected miRNA signatures have been recognized in categorizing developmental lineages and differentiation states of different tumors (Lu, et al. 2005; Rosenfeld, et al. 2008). In these roles miRNAs may function as oncomiRs (oncogenic miRNAs) or oncosuppressor miRNAs, although there is an overall downregulation of miRNAs in tumors compared to normal tissues (Lu et al. 2005). Substantial effort is currently underway to understand the molecular mechanisms associated with miRNA dysregulation to assist in early diagnosis and management of breast cancer patients.

miRNA and breast cancer

Since 2005, when miRNA deregulation was first reported in breast cancer (Iorio, et al. 2005), over 1000 studies have been published identifying and examining the role of miRNAs in breast cancer. Some of these miRNAs are regulated by E2 and/or influence expression of estrogen-responsive genes (Ferraro, et al. 2012; Klinge 2012, 2015). miRNAs have been implicated in regulating hallmarks of breast cancer (reviewed in (Goh, et al. 2015)) including cell proliferation, cell death, apoptosis, immune response, cell cycle energetics, metabolism, replicative immortality, including senescence, invasion, and metastasis (reviewed in (McGuire, et al. 2015; Negrini and Calin 2008; O’Day and Lal 2010; Singh and Mo 2013), and angiogenesis (reviewed in (Cortes-Sempere and Ibanez de Caceres 2011; Goh et al. 2015)).

Models for miRNA investigation

The process of investigating miRNAs involved in endocrine resistance usually begins with an initial profiling of miRNA differences between endocrine-sensitive versus -resistant breast cancer cell lines or between breast tumors from patients responsive and non-responsive to endocrine therapies. Methods used in these studies have included microarrays, RNA sequencing (RNA seq), and the relatively recent high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) method with confirmation by qPCR. These methods result in the acquisition of huge amounts of data that require integrative analysis and further confirmation. Computational approaches are then utilized to predict possible targets and signaling pathways that are aberrantly regulated by the identified miRNAs. Functional analysis utilizing ectopic expression and forced repression of miRNA expression are performed to validate the role of deregulated miRNAs in tumorigenesis and/or endocrine resistance in vivo and in vitro. The targets of miRNAs are further confirmed by cloning the target 3′-UTR downstream of a luciferase reporter, transfecting a cell line with this reporter plasmid to validate direct inhibition; western blots and qPCR. Target validation in clinical samples provide human significance to the study. These models have identified miRNAs involved in endocrine resistance that are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. miRNA associated with antiestrogen-resistance in breast cancer.

Experimentally proven bona fide targets and method used in confirming target are indicated. Proposed pathways associated with endocrine-resistance are included. Method of identification of targets: 3′-UTR luciferase reporter assay (L), downregulation of protein shown by western blot (W), and downregulation of target in quantitative real-time PCR assay (Q).

| miRNA | Treatment/Human Cell line/tissue | Comments | Targets (method of identification) | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putative oncomiRs based on experimental data | ||||

| miR-101 | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 μM 4-OHT 4 d in MCF-7 cells | miR-101 infected cells promote growth stimulatory activity in medium lacking E2 and TAM resistant. miR-101 has growth inhibitory activity in E2-containing medium (Sachdeva et al. 2011). | MAGI-2 ((membrane-associated guanylate kinase) (L, W) (Sachdeva et al. 2011) | Growth factor receptor (GFR) Cytoplasmic signaling |

| miR125b-5p | 0.001- 10 μM anastrozole or letrozole in LET-R MCF-7 ANA-R MCF-7 vs MCF-7aro cells; Primary breast tumors |

Upregulated in LET-R MCF-7 cells, ANA-R MCF-7 compared to MCF-7aro; high miR-125b-5p correlated with earlier relapse in ER+/PR+ patients (Vilquin, et al. 2015) | ||

| miR-128a | TAM+LET-R MCF-7 cells, MCF-7aro cells | Upregulated in TAM+LET-R MCF-7 cells vs MCF-7aro cells (Masri et al. 2010) | TGF-βRI (L, W) (Masri et al. 2010) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| MiR-181b | Human breast samples; 1 μM 4-OHT, for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h, 50 nM 4-OHT, 0, 3, 5 min T47D, TAM-R MCF-7 vs TAM-S MCF-7 |

Enhanced expression in TAM-R MCF-7 cells (Lu et al. 2011) Anti-miR-181b suppressed TAM-R xenograft tumor growth in TAM treated mice. |

TIMP3 (L W, Q) (Lu et al. 2011) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| miR-205-5p | 1, 10, 100 nM, 1, 10 μM anastrozole, 1, 10, 100 nM, 1, 10 μM letrozole; LET-R MCF-7 cells, ANA-R MCF-7 vs MCF-7aro Primary breast tumors | Upregulated in LET-R MCF-7 cells, ANA-R MCF-7 compared to MCF-7aro cells; High miR-125b-5p correlated with earlier relapse in ER+/PR+ patients (Vilquin et al. 2015) | ||

| miR-210 | Patient samples, 100 nM 4-OHT, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 d, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 |

Increased miR-210 with breast tumor histological grade. Higher in MDA-MB-231 compared to MCF-7 cells (Rothe et al. 2011) |

||

| miR-222 | Human breast samples 1 μM 4-OHT, for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h; 50 nM 4-OHT, 0, 3, 5 min T47D, TAM-R MCF-7 vs TAM-S MCF-7 |

Anti-miR-222 suppressed TAM-resistant xenograft tumor growth in TAM treated mice (Lu et al. 2011) | TIMP3 (L W, Q) (Lu et al. 2011) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| miR-221/222 | 0–65 μM 4-OHT, 6 d MCF-7/TAM-R vs MCF-7 measured in conditioned media (Wei et al. 2014) | Six-fold increase in exosomes in MCF-7/TAM-S vs MCF-7/TAM-R cells (Wei et al. 2014) | P27 and ERα (W, Q) (Wei et al. 2014) | ERα signaling/cell cycle |

| 0, 15, and 20 μM TAM, 16 h TAM-S vs TAM-R MCF-7 cells, HER2/neu (+) vs HER2/neu (−) human breast tissue | TAM increased miR-221/222 in TAM-R cells and HER2/neu (+) breast tumors compared to TAM-S MCF-7and HER2/neu (−) tumors, respectively (Miller et al. 2008) | p27(Kip1) (W, Q)(Miller et al. 2008) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling/cell cycle | |

| 0, 5, 10, 20 μM 4-OHT, 12, 24, 48 h, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | TIMP3 (W, Q) (Gan et al. 2014) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling | ||

| 10 μM 4-OHT, −/+1 nM E2, 48 h MCF-7 mammosphere transformed vs MCF-7 cells as xenografts in SCID mice | Higher in MCF-7 mammospheres compared to MCF-7 cells (Guttilla et al. 2012) | ERα (W) | EMT | |

| 100 nM fulvestrant; TAM-R MCF-7, Ful-R MCF-7, MCF-7, MCF-7-Mek5, MCF-7 TNR |

Overexpressed in Ful-R MCF-7 cells. Indirect activation of β-catenin Repression of TGF-β mediated growth inhibition (Rao et al. 2011) |

GFR Cytoplasmic signaling | ||

| 0, 5, 10, 20 μM, 10, 20, nM 4-OHT, 72 h MCF-7, T47D vs MDA-MB-468 cells Breast tumor tissue |

Higher in ERα negative MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells and primary breast tumors vs ERα positive MCF-7 and T47D cells (Zhao et al. 2008) | ERα (L, W) (Zhao et al. 2008) | ERα signaling | |

| 100 nM 4-OHT, 100 nM fulvestrant, 6 h, 2 d, TAM-sensitive MCF-7 vs TAM-resistant LY2 cells | 4-OHT upregulates miR-221/222 in LY2 TAM-resistant cells and down regulates miR-221/222 in MCF-7 cells (Manavalan et al. 2011) | ERBB3, ERα (Q) (Manavalan et al. 2011) | ERα signaling/ GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

|

| miR-301 | 300 nM 4-OHT, 24, 48, 72 h MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 | Higher in MCF-7, T47D, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-231 compared to MCF-7 10A. Higher expression in lymph node negative (LNN) invasive ductal breast cancer (Shi et al. 2011) | FOXF2, BBC3, PTEN, (L, W, Q), COL2A1 (L,Q) (Shi et al. 2011) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| miR-519a | 0, 5, 10 μM 4-OHT, 3 h, 72 h TAM-R MCF-7 vs MCF-7, HEK 293FT, breast cancer patient datasets |

Upregulated in TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells compared to TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells (Ward et al. 2014) | CDKNIA, RB1 and PTEN (L, W, Q) (Ward et al. 2014) | Cell cycle |

| miR-1280 | Patient blood samples | Higher in blood from patients with metastatic breast cancer after cytotoxic chemotherapy or undefined endocrine therapy (Park, et al. 2014) | ||

| Putative oncosuppressor miRNAs based on experimental data | ||||

| Let-7b/Let-7i | TAM-R MCF-7, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 Breast cancer tissues |

Overexpression of Let-7b/Let-7i enhanced sensitivity of TAM-R MCF-7 cells to TAM only in hormonal withdrawal medium and not in normal growth medium (Zhao et al. 2011) | ERα36 (L, W, Q) (Zhao et al. 2011) | ERα signaling |

| Let-7i | 5, 10, 15 and 20 μM 4-OHT, 48 h, ZR-75-1 cells | Overexpression of Let-71 increased TAM-sensitivity in ZR-75-1 cells Inverse correlation of Let-7i and TNF receptor associated factor (TRAF)1 (Weng, et al. 2014) |

Apoptosis/cell survival signaling | |

| miR-10a | Primary breast tumors | Higher expression in patient tumors was associated with longer relapse-free time. Increased expression predicted tumor relapse in TAM-treated ER+ postmenopausal breast cancer patients (Hoppe, et al. 2013) | ||

| miR-15a/16 | 100 pM E2, 1 μM 4-OHT, 100 nM fulvestrant, E2+4-OHT, E2+ICI, for 24 h, 24 h, 72 h TAM-R MCF-7/HER2Δ16 vs MCF-7/HER2 cells (Cittelly et al. 2010a) |

Suppressed expression of miR-15a and miR-16 in HER2Δ16 mutant cells associated with inverse expression of BCL-2 protein and mRNA and decreased sensitivity to TAM and ICI (Cittelly et al. 2010a) | Apoptosis/cell survival signaling | |

| miR-30a-3p | Patient samples (Rodriguez-Gonzalez, et al. 2011) | Increased expression in ER+ primary breast tumors of patients who received TAM and showed longer progression-free survival; Inverse correlation with HER2 and RAC1 cell motility signaling pathways (Rodriguez-Gonzalez et al. 2011) | ||

| miR-126 | Primary breast tumors | Higher expression in patient tumors was associated with longer relapse-free time. Increased expression predicted tumor relapse in TAM-treated ER+ postmenopausal breast cancer patients (Hoppe et al. 2013) | ||

| miR-200b/200c | 100 nM 4-OHT, 100 nM fulvestrant, 6 h, 2 d, TAM-S MCF-7 vs TAM-R LY2 (Manavalan et al. 2013) |

Decreases in TAM-resistant LCC1, LCC2, LCC9 and LY2 cells vs MCF-7 cells (Manavalan et al. 2013) | ZEB1/2 (W, Q) (Manavalan et al. 2013) | EMT |

| 100 nM 4-OHT, 100 nM ICI, 6 h, 2 d, TAM-sensitive MCF-7 vs TAM-resistant LY2 | Increased in TAM-sensitive MCF-7 and decreased in TAM-resistant LY2 cells (Manavalan et al. 2011) | CYP1B1(Q) (Manavalan et al. 2011) | ||

| miR-342-3p | 24h 100 pM E2, 1μM 4-OHT, E2+4-OHT in TAM-R MCF-7/HER2Δ16, MCF-7/HER2, TAMR1, LCC2 cells, Breast tumors (Cittelly et al. 2010b) | Downregulated in TAM-R MCF-7/HER2Δ16 cell, TAMR1, LCC2 cells and TAM refractory human breast tumors vs MCF-7 cells and TAM-S tumors. TXNIP is an indirect target of miR-342 (Cittelly et al. 2010b) | BMP7, GEMIN4 (microarray, L, Q,) SEMAD(microarray, Q) (Cittelly et al. 2010b) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| Primary breast tumors 10 nM E2, 20 μM 4-OHT, 72 h, MCF-7 vs SKBR-3 & MDA-MB-231 cells |

Decreased in ERα (−) SKBR-3 and MDA-MB-231 cells vs MCF-7 cells. Direct correlation between miRNA-342 expression and ERα expression (He et al. 2013) |

ERα signaling | ||

| miR-375 | 5 μM 4-OHT TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells vs TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells | Lower in TAM-R MCF-7 vs MCF-7 cells (Ward et al. 2013) | MTDH (L, W, Q) (Ward et al. 2013) | EMT |

| miR-424-3p | 0.001-10 μM anastrozole or letrozole; LET-R MCF-7 cells, ANA-R MCF-7 vs MCF-7aro Primary breast tumors |

Downregulated in LET-RMCF-7 cells, ANA-R MCF-7 compared to MCF-7aro (Vilquin et al. 2015) | ||

| miR-451 | 1 μM 4-OHT for 0 h, 4 h, 8 h 24h TAM-R MCF-7 vs TAM-S MCF-7 cells |

Reduced levels in TAM-R vs TAM-S MCF-7 cells (Bergamaschi and Katzenellenbogen 2012) | 14-3-3ς (W, Q) (Bergamaschi and Katzenellenbogen 2012) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| miR-574-3p | 1μM 4-OHT, MCF-7 cells/tissue sample | Lower in TAM-R MCF-7 cells and clinical breast cancer tissues compared to TAM-S MCF-7cells and adjacent normal control, respectively (Ujihira et al. 2015) | Clathrin heavy chain (CLTC) ( L, W, Q) (Ujihira et al. 2015) | GFR Cytoplasmic signaling |

| miR-873 | 1, 10, 100 nM, 1, 5 μM 4-OHT, 7 d MCF-7/TAM-R vs MCF-7 cells and xenograft tumors |

Downregulated in TAM-R MCF-7 and breast tumors compared to TAM-S and normal tissues, respectively. | cyclin-dependent kinase 3 (CDK3) (L, W, Q) (Cui et al. 2014) | Repressed ERα transcriptional activity (Cui et al. 2014). |

Abbreviations: 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT); TAM-sensitive (TAM-S); TAM-resistant (TAM-R); letrozole-resistant (LET-R), Anastrozole-resistant (ANA-R); Fulvestrant-resistant (Ful-R). MCF-7aro cells are MCF-7 cells stably overexpressing aromatase

Table 2. Exosomal miRNAs described in breast cancer.

↑ Increased expression; ↓ Reduced expression.

| Extravessicular (EV) miRNA composition | Direction of miRNA expression | Sample source | Time in culture prior to harvesting exosome | comments | Targets analyzed in study | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | Patient | Xenograft | ||||||

| miR-21, let-7a, miR-100, miR-125b, miR-720, miR-1274a, and miR-1274b miR-205 |

↑ ↓ |

MCF-7 MCF10A |

No | No | 72 h | (Guzman, et al. 2015) | ||

| miR-10a, miR155, miR-373, miR-10b, miR-21, miR-27a | ↑ | MCF-7 MCF-10A NMuMG MDA-MB-231 |

Yes | Yes | 24 h 72 h |

OncomiRs miR-10b and miR-21 confirmed by northern blot. | (Melo, et al. 2014) | |

| miR-10b and miR-10a, miR-218, miR10a, miR-99a, miR-142-3p; miR-32, miR-138, miR-7e, miR-106b | ↑ | MCF-7 MDA-MB-231 MCF-10A HMLE HEK-293T |

No | No | 48 h | OncomiR | HOXD10 and KLF4 (L, W; targets for miR-10b) | (Singh, et al. 2014) |

| miR-140 miR-29a, and miR-21 |

↓ ↑ |

MCF-10DCIS MCF-7 MDA-MB-231 HEK-293T |

No | No | 3 d | (Li, et al. 2014) | ||

| miR-373, miR-101, and miR-372 | ↑ | MCF-7 | Yes (Serum) | No | Serum used | High in TNBC; Over-expression of miR-373 promotes loss of ER and resistance to Camptothecin | (Eichelser, et al. 2014) | |

| miR-221/222 | ↑ | MCF-7 TAM-R/MCF-7 |

No | No | 72 h | Exosomal transport may be an additional mechanism by which miR-221/222 promote TAM-R | P27 (Q, W), ERα (Q, W) | (Wei et al. 2014) |

| miR-23a, miR1246 | ↑ | MCF-7 MCF-7/Doc |

No | No | 12 h 24 h |

May contribute to Cisplatin resistance | (Chen, et al. 2014a) | |

| miR-100, miR-17, miR-222, miR-342-3p,miR-451 and miR-30a | ↑ | MCF-7 MCF-7/Adr MCF-7/Doc |

No | No | 72 h | PTEN (Q; target for miR-222) | (Chen, et al. 2014b) | |

| let-7a, miR-328, miR-130a, miR-149, miR-602, and miR-92b miR-198 |

↑ ↓ |

MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 | No | No | (Kruger, et al. 2014) | |||

| miR-16 | ↑ | MSCs 4T1 SVEC |

No | No | 48 h | VEGF (Q) | (Lee, et al. 2013) | |

| miR-16, miR-720, miR-451, miR-1246 | ↑ | MCF-7 MDA-MB-231 |

No | No | 5 d | (Palma et al. 2012) | ||

| miR-451, miR-1246 | ↑ | MCF-7 MDA-MB-231 SKBR3 BT-20 |

No | No | 5 d | (Pigati, et al. 2010) | ||

| miR-223 | ↑ | Macrophages SKBR3 MDA-MB-231 |

No | No | 24 to 48 h | Released by macrophages and promotes breast cancer cell invasion | Mef2c (L,W) | (Yang, et al. 2011) |

| miR-210 | ↑ | MCF7 | No | No | 48 h | Released in response to hypoxia | (King, et al. 2012) | |

Abbreviations: Adriamycin (Adr); (Dox) = doxorubicin (Dox)Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), Mouse breast cancer cell line (4T1), mouse endothelial cell line (SVEC), nontumorigenic mouse mammary epithelial cells (NMuMG), human mammary epithelial (HMLE) cell line, MCF-10 ductal carcinoma in situ cells (MCF-10DCIS);

There are limitations to these approaches. For example, integrative analysis for identifying aberrantly expressed miRNAs is limited by the set of computational parameters used in the study and rarely are these parameters applied to other studies. Functional investigations need to be performed for each miRNA and its target. The acquisition of massive amounts of information which, though relevant, do not often translate to physiological significance necessitates further studies within clinical settings. HITS-CLIP is technically challenging and complex, requiring great skill, but has the advantage of capturing interactions ‘frozen’ by UV-crosslinking under physiological conditions without the use of exogenous crosslinking agents which can lead to artificial interactions (Moore, et al. 2014).

miRNAs regulating ERα protein and signaling

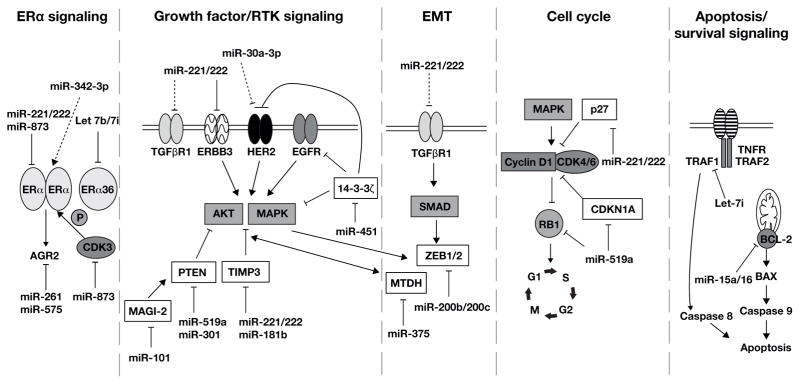

The role of miRNAs in promoting endocrine resistance is exemplified by, but not limited to, their involvement in regulating ERα (Figure 2). Decreased ERα expression is involved in endocrine-resistant breast cancer progression. miRNAs including miR-221/222 (Zhao, et al. 2008), miR-342-3 p (He, et al. 2013), miR-873 (Rothe, et al. 2011) and Let7b/Let-7i (Zhao, et al. 2011) downregulate ERα protein expression (Table 1). miR-221 and miR-222 are overexpressed in TAM-resistant and ERα-negative breast cancer cell lines and tumors (Manavalan, et al. 2011; Miller, et al. 2008; Zhao et al. 2008). The 3′UTR of ERα is a direct target of miR-221/222 decreasing ERα protein but not mRNA (Zhao et al. 2008). Transient overexpression of miR-221/222 in TAM-sensitive MCF-7 and T47D cells resulted in TAM resistance whereas downregulation of miR-221/222 in ERα negative/TAM-resistant MDA-MB-468 cells restored ERα expression and sensitized cells to TAM-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Zhao et al. 2008). ERα is not a direct target of miR-342-3p, but loss miR-342-3p was associated with a concomitant loss in ERα expression and resulted in TAM resistance (He et al. 2013). Conversely, forced overexpression of miR-342-3p sensitized MCF-7 cells to TAM-induced apoptosis (He et al. 2013). The exact mechanism promoting loss of ERα expression upon downregulation of miR-342-3p is yet to be determined (van Schooneveld et al. 2015).

Figure 2. Established targets of miRNAs in endocrine resistant breast cancer.

miRNAs associated with ERα signaling, growth factor/RTK signaling, EMT, dysregulation of cell cycle kinetics, and apoptosis and their targets in these pathways involved in endocrine resistance are shown. The miRNAs and their targets are described in the text and summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The established, bona fide targets are indicated with solid black lines. The dotted arrows indicate observed correlations with unknown mechanisms.

Increased expression of ERα splice variants has also been reported to be associated with poor prognosis and contribute to endocrine resistance (Li, et al. 2013a; Shi, et al. 2009). ERα36 is an N-terminal truncated 36 kDa variant of full-length ERα (ERα66) (Wang, et al. 2006). ERα36 lacks AF-1 and AF-2 of ERα66, retains DNA binding and dimerization domains, and binds E2, but is not inhibited by TAM or fulvestrant (Wang et al. 2006). ERα36 is expressed in ERα-negative breast cancer cells and tumors (Zhang, et al. 2012) and overexpressed in TAM-resistant breast cancer cells (Li et al. 2013a). Increased ERα36 protein expression is proposed to be mediated by decreased let-7 since transfection of let-7b and let-7i mimics repressed ERα36 expression and sensitized TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells to TAM growth inhibition (Zhao et al. 2011). Let-7 family members are downregulated in breast cancer tissues and TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells (Vadlamudi, et al. 2001; Zhao et al. 2011).

ERα is regulated by post-translational modifications including phosphorylation, methylation, sumoylation, and palmitoylation (Acconcia, et al. 2004; Cui, et al. 2014; Li, et al. 2003; Sentis, et al. 2005; Zhang, et al. 2013). These modifications influence ERα interaction with other molecules, including transcriptional coregulators, hence regulating gene transcription (Figure 1). These post-translational events also contribute to endocrine resistance (Anbalagan and Rowan 2015). miRNAs are implicated in altering post-translational ERα modifications to promote TAM resistance (Cui et al. 2014). For example, miR-873 targets CDK3, which phosphorylates ERα at Ser104/116 and Ser118 (Cui et al. 2014). miR-873 expression was downregulated in TAMR/MCF-7 breast cancer cells and forced overexpression of miR-873 in these cells reversed TAM resistance and decreased xenograft tumor growth. The authors postulated that the decrease in miR-873 resulted in enhanced ERα phosphorylation and ligand-independent activity in TAMR/MCF-7 cells (Cui et al. 2014).

miRNA regulation of ERα protein interactors in breast cancer

ERα interacts with other transcription factors, e.g., AP-1, Sp-1, NFκB, and forkhead transcription factor (FOXM1), to regulate gene expression (Petz, et al. 2002; Pradhan, et al. 2010; Sanders, et al. 2013). Increased activity of these transcription factors is associated with endocrine resistance (Bergamaschi, et al. 2014; Johnston et al. 1999; Schiff, et al. 2000; Zhou et al. 2007). FOXM1 is overexpressed in many cancers, including breast cancer, and its ectopic expression promotes cell invasiveness (Bergamaschi et al. 2014). Repression of FOXM1 was associated with increased miR-211 (Song and Zhao 2015) and miR-23a (Eissa, et al. 2015), and repressed breast cancer cell growth, migration and invasion in animal models.

Activation of NFκB contributes to endocrine-resistance in breast cancer (Keklikoglou, et al. 2011). A genome-wide miRNA screen in HEK-293T cells identified 13 miRNAs regulating NFκB transcriptional activity (Keklikoglou et al. 2011). Subsequent studies in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells demonstrated that miR-570 and miR-373 inhibited TGFα-activation of NFκB-induced transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g., IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1 and ICAM-1, and TGF-β signaling by direct targeting of RELA and TGFBR2. The authors reported that transient overexpression of miR-520 or miR-373 inhibited TGF-β induced MDA-MB-231 cell invasion. While they did not detect miR-373 in human breast tumors, a correlation of higher miR-520c expression in ERα-tumors and lower TGFBR2 transcript expression was observed, allowing the authors to suggest loss of miR-520 expression may play a role in ERα-tumor progression via altered NFκB signaling (Keklikoglou et al. 2011).

The nuclear receptor coactivator proline glutamic acid leucine rich protein (PELP1) interacts with ERα (Vadlamudi et al. 2001) to modulate genomic (Nair, et al. 2004) and nongenomic functions of ERα (Barletta, et al. 2004; Vadlamudi, et al. 2005). As a proto-oncogene, PLEP1 is upregulated during breast cancer metastasis and promotes human breast tumor xenograft growth in nude mice (Rajhans, et al. 2007; Roy, et al. 2012; Vadlamudi et al. 2005). In MCF-7 cells, cytoplasmic localization of PELP1 conferred resistance to TAM (Vadlamudi et al. 2005). Although the mechanisms of PELP1 promotion of TAM resistance is not fully known, the binding of PELP to the proximal promoters of the oncosuppressors miR-200a and miR-141 recruited histone-deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) and repressed their transcription (Roy, et al. 2014). The attendant decrease in miR-200a and miR-141 was suggested to stimulate metastatic growth (Becker, et al. 2015).

ERα coactivator nuclear receptor co-activator 3 (NCOA3, also known as SRC-3 (Liao, et al. 2002) and AIB1 (Anzick, et al. 1997b) is overexpressed in 50% breast tumors (Anzick, et al. 1997a). Targeting SRC-3 is of clear clinical interest (Tien and Xu 2012). SRC-3 overexpression results in constitutive activation of ERα-mediated transcription, breast tumor growth, and resistance to TAM in vivo and in xenograft models (List, et al. 2001; Ring and Dowsett 2004). SRC-3 translation is repressed by miR-17-5p. Overexpression of miR-17-5p in MCF-7 cells repressed E2-induced proliferation and endogenous cyclin D1 transcription (Hossain, et al. 2006). MiR-195 negatively regulates SRC-3 in human hepatoma cells (Jiang, et al. 2014), but whether it does so in breast cancer is unknown.

ERα corepressors including nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCoR1) influence gene transcription by recruiting HDAC complexes to promote chromatin condensation and repression of gene transcription (Lavinsky, et al. 1998; Ring and Dowsett 2004). NCoR1 is reduced in TAM-resistant MCF-7 xenograft tumors grown in nude mice (Lavinsky et al. 1998). However, both NCoR and the corepressor SMRT stimulated 4-OHT-ERα agonist activity on an ERE-driven luciferase reporter in transiently transfected Rat-1 cells. Blockage of NCoR1 promoted the agonistic activity of TAM (Lavinsky et al. 1998). To our knowledge, there are no reports of miRNA regulation of NCoR1. However, inhibition of miRNA synthesis by knocking down DICER in LNCaP prostate cancer cells increased NCoR1 transcription and likewise, NCoR1 increased in the prostate of DICER−/− mice (Narayanan, et al. 2010). Conversely ectopic expression of DICER mediates metastasis and TAM resistance in breast cancer cells (Selever, et al. 2011).

miRNA activation of growth factor receptor signaling in endocrine resistance cancer

Endocrine resistant breast cancer cells and tumors show increased EGFR signaling (Aiyer, et al. 2012). Although trastuzimab is a targeted therapy widely used in patients whose breast tumors overexpress HER2, these patients also benefit from TAM (Huynh and Jones 2014). Unfortunately, overexpression of an isoform of HER2, HER2Δ16, which is associated with metastasis (Mitra, et al. 2009), also promotes TAM resistance (Cittelly, et al. 2010a; Cittelly, et al. 2010b). Decreased expression of miR-15a, miR-16, and miR-342-3p contribute to endocrine resistance in TAM-resistant MCF-7/HER2Δ16 breast cancer cells (Cittelly et al. 2010a; Cittelly et al. 2010b). miR-342 was also downregulated in TAM-non-responsive breast tumors and HER2 negative, TAM-resistant TAMR1 and LCC2 cells (Cittelly et al. 2010b). Transient overexpression of miR-342 resensitized TAM-resistant MCF-7/HER2Δ16 and TAMR1 cells to TAM-induced apoptosis; decreased BMP7, GEMIN4, and SEMAD are proposed as direct miR-342 targets mediating this response. However, the role of these targets in directly promoting TAM resistance was not examined.

Decreased miR-451 also regulates mitogenic signaling to promote TAM resistance (Bergamaschi and Katzenellenbogen 2012). TAM, but not raloxifene or fulvestrant, downregulates miR-451 in TAM- resistant cells (Bergamaschi and Katzenellenbogen 2012). Downregulation of miR-451 was associated with upregulation of its target protein 14-3-3ζ, a scaffolding protein whose high expression is correlated with early time to disease recurrence in patients treated with TAM. Overexpression of miR-451 in MCF-7 cells decreased 14-3-3ζ and reduced activation of HER2, EFGR, and MAPK signaling, resulting in decreased cell proliferation and migration and increased apoptosis. In addition, overexpression of miR-451 restored the inhibitory effectiveness of SERMs in TAM-resistant cells.

A recent paper used a miRNA library screen to identify miRNAs associated with TAM sensitivity in MCF-7 cells (Ujihira, et al. 2015). The authors identified miR-105-2, miR-877, let-7f, miR-125a and miR-574-3p as “dropout” miRNAs that were downregulated in 4-OHT-treated compared to vehicle control-treated MCF-7 cells. Of these miRNAs, miR-574-3p was found to be downregulated in breast cancer tissue samples compared to adjacent normal tissue samples. Luciferase reporter assays and knockdown or overexpression of miR-574-3p identified clathrin heavy chain (CLTC) as a bona fide miR-574-3p target. Low CLTC transcript levels were correlated with better survival in breast cancer patients. This study outlines a new role of miR-574-3p in mediating TAM responses: however, whether upregulation of miR-574-3p will sensitize TAM-resistant cells to TAM remains to be determined.

Earlier, we discussed downregulation of ERα protein by increased miR-221/222 in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Dysregulation of miR-221/222 was also reported to regulate multiple stages of RTK pathways to promote anti-endocrine resistance. In vitro analysis confirmed miR-221/222 was increased in endocrine resistant HER2 positive primary human breast cancer tissues compared to HER-2 negative tissue samples (Miller et al. 2008). Overexpression of miR-221/222 made TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells resistant to TAM and decreased protein expression of its known target p27. Overexpression of p27 enhanced TAM-induced cell death in TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells (Miller et al. 2008). The same lab reported that repression of miR-222 and miR-181b suppressed growth of TAM-resistant MCF-7 tumor xenografts in mice (Lu, et al. 2011). Reduced expression of tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 (TIMP3), a common target of miR-221/222/181b, in primary breast carcinomas was also reported to mediate TAM resistance by relieving repression of ADAM10 and AMAM17. ADAM10 and AMAM17 are critical for growth of TAM-resistant cells (Lu et al. 2011). Ectopic expression of TIMP3 repressed growth of TAM-resistant cells and reduced phosphoMAPK- and EGF- induced phosphoAKT levels. Conversely, repression of TIMP3 in TAM-sensitive MCF-7 promoted phosphorylation of MAPK and AKT, and desensitized the cells to growth inhibition by TAM in vitro and in vivo. In another study, the same group showed that sensitivity to TAM upon inhibition of miR-221/222 was unique to ERα positive MCF-7 cells and not ERα-negative MDA-MB-231 cells, although TIMP3 was a miR-221/222 target in both cells (Gan, et al. 2014).

By promoting cell growth, miR-221/222 also promotes resistance to fulvestrant (Rao, et al. 2011). Ectopic expression of miR-221/222 in TAM-resistant MCF7 and TAM-resistant BT474 cells increased β-catenin and relieved TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition. Inhibition of β-catenin decreased estrogen-independent growth in pre-miR-221/222-transfected MCF-7 cells (Rao et al. 2011). The TGF-β signaling pathway was inhibited in letrozole-resistant, aromatase-stably transfected MCF-7 (T+LET R) breast cancer cells and miR-128a was upregulated in these cells (Masri, et al. 2010). miR-128a targeted and repressed TGF-βR1 (TGF-β receptor 1) protein expression in T+LET R cells compared to the parental MCF-7 cells stably transfected with aromatase (MCF-7aro). Repression of miR-128a re-sensitized T+LET R cells to TGF-β growth inhibition.

Loss of PTEN is associated with poor outcome in HER2+ breast tumors (Stern, et al. 2015). PTEN is downregulated by miR-101 (Sachdeva, et al. 2011). Overexpression of miR-101 promotes MCF-7 cell growth and TAM resistance in estrogen-free growth medium but suppressed cell growth in E2-containing medium (Sachdeva et al. 2011). TAM resistance was mediated by Akt activation and was independent of ERα expression. miR-101 repressed its target MAGI-2 (membrane associated guanylate kinase), a scaffolding protein required for PTEN activity, thus reducing PTEN activity leading to activation of Akt. PTEN is also a bona fide target of the oncomiR miR-301 (Shi, et al. 2011). Transient repression of miR-301 in MCF-7 cells decreased cell viability and sensitized cells to TAM (Shi et al. 2011).

miRNAs as cell cycle regulators in endocrine-resistance

SERMs can be cytostatic and cytotoxic by promoting G1-phase cell cycle arrest (Subramani, et al. 2015). miR-221/222 (Miller et al. 2008) and miR-519a (Ward, et al. 2014) have been implicated in altering expression of molecular regulators of the cell cycle to promote endocrine resistance. miR-221/222 represses p27 to promote TAM resistance in breast cancer cells (Miller et al. 2008; Wei, et al. 2014).

Recently, miR-519a was reported as a novel oncomiR by increasing cell viability and cell cycle progression (Ward et al. 2014). miR-519a was upregulated in TAM- resistant MCF-7 cells compared with TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells. Elevated levels of miR-519a in primary breast tumors were associated with reduced disease-free survival in ERα+ breast cancer patients and miR-519a was suggested to contribute to TAM resistance. Knockdown of miR-519a in TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells sensitized the cells to TAM growth inhibition. Concordantly, overexpression of miR-519a in TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells desensitized the cells to TAM by preventing growth inhibition while promoting caspase activity and apoptosis. Tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) involved in PI3K signaling CDKNIA (which encodes p21), RB1, and PTEN, were reported to be bona fide targets of miR-519a, although the role of these targets in mediating TAM-resistance have not been explored.

miRNAs in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

Changes involved in tumor progression include acquisition of migration/invasion, gain of front-rear polarity, resistance to anoikis, and mesenchymal transition (Howe, et al. 2012). Genetic changes that occur during EMT include but are not limited to activation of SNAIL, increased Zinc-finger E-box-binding 1 (ZEB1), reduced E-cadherin, and increased vimentin and N-cadherin (Lamouille, et al. 2014). EMT is also implicated as a mechanism by which tumors enact resistance to TAM (Steinestel, et al. 2014).

To identify miRNAs that mediate TAM resistance, we used a microarray to identify miRNAs differentially regulated between endocrine-sensitive MCF-7 cells and an endocrine -resistant MCF-7 variant LY2 cells, with selected results confirmed by qPCR (Manavalan et al. 2011). Among these, miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c were found to be downregulated in LY2 cells and other TAM-resistant breast cancer cell lines (LCC9) compared with parental TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells (Manavalan et al. 2011; Manavalan, et al. 2013). The decrease in miR-200 family expression was associated with increase in ZEB1. ZEB1 is an EMT-inducing transcription factor that represses E-cadherin (Hurteau, et al. 2007). Ectopic expression of miR-200b and/or miR-200c altered LY2 morphology to a more epithelial-like phenotype and inhibited cell migration. These phenotypic changes were associated with repression of the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin, vimentin, and ZEB1 and an increase in the epithelial marker E-cadherin. Further, upregulation of miR-200b/200c or ZEB1 knockdown sensitized LY2 cells to TAM- and fulvestrant-induced growth inhibition. However, overexpression of miR-200b/200c in MCF-7 cells did not promote resistance to TAM or fulvestrant, indicating that cellular changes in addition to downregulation of miR-200 family members are involved in TAM resistance in LY2 cells.

In another miRNA microarray study, miR-375 was found to be downregulated in a mesenchymal TAM-resistant MCF-7 cell line model (Ward, et al. 2013). Re-expression of this miR-375 sensitized TAM-resistant cells to TAM and reduced invasiveness by decreasing expression of mesenchymal markers fibronectin, ZEB1, and SNAI2 while increasing the epithelial markers E-cadherin and ZO-1. This resulted in partial reversal of EMT called MET (mesenchymal-to-epithelial transformation). Metadherin (MTDH), a cell surface protein upregulated in breast tumors that mediates metastasis (Brown and Ruoslahti 2004), was identified as a direct, bona fide miR-375 target mediating this response. TAM- treated patients whose primary tumor showed high MTDH showed shorter-disease-free survival and a higher risk of relapse. This study exemplifies the role of miRNAs in mediating cellular transformations that foster tumor progression and TAM resistance

EMT allows the emergence of cancer stem cells (CSCs) that have properties including self-renewal potential and tumorigenicity (Singh and Settleman 2010; Ward et al. 2013). Mammosphere culture is widely utilized to enrich the population of mammary epithelial stem cells and breast CSCs in vitro (Charafe-Jauffret, et al. 2009; Dontu, et al. 2003). Mammosphere culture of MCF-7 cells (MCF-7M cells) resulted in permanent EMT with increased miR-221/222 and loss of their target ERα mRNA expression (Guttilla, et al. 2012). MCF-7M cells were also characterized by downregulation of epithelial-associated tumor suppressor miRNAs including miR-200c, miR-203 and miR-205. MCF-7M cells were resistant TAM-induced cell death. These data reinforce other studies discussed above demonstrating a role for increased expression of miR-221/222 in driving TAM-resistance.

miRNAs as regulators of apoptosis/cell survival signaling

Tumor growth reflects a balance between cell growth and cell death. Endocrine inhibitors activate apoptotic and stress signals to inhibit breast cancer cell growth (Mandlekar and Kong 2001; Musgrove and Sutherland 2009; Riggins et al. 2005). However, the molecular mechanisms behind these observations are yet to be fully defined. Activation of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL-2, crosstalk between apoptotic effects of antiestrogens and the TNF-α pathway, and promotion of survival signals including PI3k-Akt and NF-κB have been documented to promote resistance endocrine therapy (Riggins et al. 2005). MiRNAs can directly target antiapoptotic transcripts or regulate mediators of the survival signaling pathways. For example, low miR-15a/16 expression correlated with upregulation of BCL-2 in TAM- and fulvestrant- treated TAM- resistant MCF-7/HER2Δ16 cells and xenograft tumor promotion in vivo (Cittelly et al. 2010a). RNAi targeting of BCL-2 or reintroduction of miR-15a/16 decreased TAM-induced BCL-2 expression in TAM- resistant MCF-7/HER2Δ16 cells resulting in TAM-induced decrease in cell growth and promotion of apoptosis. Conversely, repression of miR-15a/16 in TAM-sensitive MCF-7/vector or MCF-7/HER2 increased BCL-2 expression and promoted resistance to TAM by inhibiting apoptosis and preventing growth inhibition.

To identify potentially ethnic group-specific TAM sensitivity biomarkers, Weng et al. performed an integrative genomic analysis on 58 African-derived HapMap YRI lymphoblastoid cell lines (YRI LCLs; breast cancer cells) (Bradley and Pober 2001). Genetic variants (including 50 SNPs with effects on 34 genes and 30 miRNAs) were identified to be sensitive to endoxifen, an active metabolite of TAM. Among the genes identified, increased TNF receptor-associated factor 1 (TRAF1) and decreased let-7i expression correlated with endoxifen resistance in 44 YRI LCLs. TRAFs are intracellular signal transducers for death receptor superfamily TNF receptor (TNFR) (Bradley and Pober 2001). TRAF1 associates with TRAF2 to form a protein complex that interacts with inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein (IAP) to mediate anti-apoptotic signals (MAPK8/JNK and NF-κB) from the TNF receptor (Wajant, et al. 2003; Wang, et al. 1998). Repression of TRAF1 or overexpression of let-7i in ZR-75-1 luminal breast cancer cells enhanced sensitivity to TAM and decreased the number of viable cells. These data show that by regulating death signals, miRNAs can also mediate response to antiestrogens.

Extracellular vesicular (exosomes) transport of miRNAs in endocrine resistance

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), produced by outward budding of the PM, contain proteins and nucleic acids that can be transported in blood between tissues and cells (Chiba, et al. 2012; Gong, et al. 2012). The contents of EVs can facilitate tumor growth including angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, and immune suppression. They also play a role in reducing effectiveness of drugs (Chen, et al. 2014c). Exosomes are smaller EVs of endosomal origin and formed by the fusion of multivesicular bodies with PMs (Johnstone, et al. 1987; Jung, et al. 2012). Exosomes transport miRNAs in circulation. Mechanisms of exosomal formation and delivery are cell-specific and display proteins from their tissue of origin and are specific to the target cells (Braicu, et al. 2015; Clayton, et al. 2001; Simpson, et al. 2009). It was initially reported that miRNAs were randomly packaged into exosomes with no specific miRNA preferentially incorporated (Skog, et al. 2008; Valadi, et al. 2007). Studies now indicate different miRNAs are associated with specific customized exosomes (Palma, et al. 2012). However, the selection mechanism for incorporating miRNAs into exosomes is yet to be elucidated.

EVs or exosomal delivery of miRNAs is thought to play roles in breast tumorigenesis and metastasis (Table 2). Cell culture studies showed that exosomes secreted by TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells were larger in size and number compared to TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells and were taken up by the TAM-sensitive cells (Wei et al. 2014). This study showed that miR-221/222 were released from exosomes into TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells resulting in reduction of their target genes p27 and ERα, and enhanced TAM resistance. Transfection of a miR-221/222 inhibitor in MCF-7 cells treated with TAM-resistant MCF-7 exosomes reduced TAM-resistance. These data again support the importance of miR-221/222 in TAM resistance in MCF-7 cells.

The potential use of exosomal miRNAs as candidate biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis remains to be definitively proven. The manipulation of exosomal miRNAs suggest a new therapeutic approach for drug delivery, but requires further research.

miRNAs of unknown function in endocrine resistance

Other microRNAs identified by microarray or library screen and confirmed by qPCR to promote antiestrogen resistance in breast cancers, but having undetermined functional roles include: miR-10a, miR-21, miR-22, miR-29a, miR-181a, miR-125b, miR-205 which mediate resistance to TAM (Manavalan et al. 2011); and miR-125a and miR-877 which also mediate TAM resistance (Ujihira et al. 2015) Other miRNAs identified by integrative analysis to make up network clusters that contribute to antiestrogen resistance include: miR-146a, miR-27a, miR-145, miR-21, miR-155, miR-125b, and let-7s (Xin, et al. 2009).

Roles of Drosha, DICER, and AGO2 in endocrine resistance

As described earlier in this review, Drosha and DICER function in miRNA processing. The role of Drosha in endocrine resistance has not been ascertained, despite the observation that reduced cytoplasmic Drosha is predictive of better endocrine therapy response (Khoshnaw, et al. 2013).

Loss of DICER is predictive of a better response to endocrine therapy (Khoshnaw, et al. 2012). Elevated DICER was associated with TAM resistance in metastatic breast tumors and tumor xenografts (Selever et al. 2011). DICER-overexpressing cells were enriched with the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily that causes resistance to several chemotherapeutic agents (Doyle and Ross 2003). Increased BCRP resulted in a more efficient efflux of TAM in DICER-overexpressing cells compared to control cells. Inhibition of BCRP inhibited TAM efflux and restored TAM sensitivity in DICER-overexpressing cells. In ERα negative breast cancer cells, DICER is targeted by oncogenic miRNAs including miR-103/107 (Martello, et al. 2010), let-7, miR-222/221, and miR-29a (Cochrane, et al. 2010). Whether repression of DICER by these miRNAs mediates endocrine resistance is yet to be determined.

AGO2 recruits mRNA and miRNA into the RISC complex and is the catalytic component of the RISC complex. AGO2 is elevated in ERα negative compared to ERα positive breast cancer cell lines and tumors (Adams, et al. 2009). Expression of AGO2 is mediated by ERα/estrogen signaling and EGFR/MAPK signaling pathways (Adams et al. 2009). Ectopic expression of full length AGO2 in MCF-7 cells promoted cell proliferation, reduced cell-cell adhesion, and increased cell migration (Adams et al. 2009). Whether AGO2 plays a role in endocrine resistance is yet to be determined.

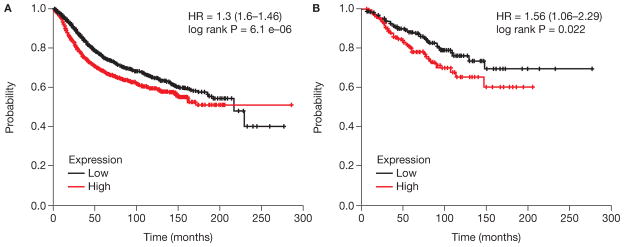

We examined the association of AGO2 expression and overall survival rate in breast cancer patients using the online survival analysis tool, Kaplan–Meier Plotter (http://kmplot.com/backup/breast) (Gyorffy, et al. 2013). It assesses the association gene expression on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data from 3554 patients. The patient data are from GEO. Higher AGO2 expression correlates with reduced relapse-free survival in all breast cancer patients and those whose primary tumors are ER+/PR+ (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Higher expression of AGO2 is statistically associated with decreased relapse-free survival in all breast cancer and in patients whose primary tumors are ERα+/PR+.

The Kaplan-Meier plots of AGO2 expression in breast tumors with breast cancer survival were generated using http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service (Gyorffy, et al. 2010). A) All breast tumors, n = 3557; B) ERα+/PR+, n = 701.

Conclusion

miRNAs are dysregulated in endocrine-resistant breast cancer and these miRNAs regulate specific genes in growth-promoting, apoptosis-resistant, and EMT pathways that result in TAM- and AI- resistance (Tables 1 and 2). The involvement of exosomes containing miRNAs in mediating endocrine resistance provides a new target for biomarker identification and therapeutic intervention to block metastatic spread. Although identifying new miRNAs mediating endocrine resistance is important, research effort is needed to determine the mechanisms and functional roles of already identified miRNAs with unknown roles in endocrine resistance and to develop “targeted” therapeutics to counter miRNA dysregulation and enhance hormonal sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 CA138410 and in part by a grant from the University of Louisville School of Medicine to C.M.K.

Abbreviations

- 4-OHT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- AI

aromatase inhibitors

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- E2

estradiol

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ERE

estrogen response element

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EtOH

ethanol

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ERα

estrogen receptor α

- ERβ

estrogen receptor β

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- GPER/GPR30

G-protein coupled ER

- HITS-CLIP

high-throughput RNA-seq isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation

- IGFR

insulin-like growth factor receptor, MET, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition

- miRNA

microRNA

- PM

plasma membrane

- QRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- RAL

raloxifene

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- SERMs

selective ER modulators

- SERDs

selective ER downregulators

- TAM

tamoxifen

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Author contributions:

Both authors contributed equally to the writing of this review.

References

- Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. . Lancet. 1998;351:1451–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acconcia F, Ascenzi P, Fabozzi G, Visca P, Marino M. S-palmitoylation modulates human estrogen receptor-alpha functions. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;316:878–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams BD, Claffey KP, White BA. Argonaute-2 expression is regulated by epidermal growth factor receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and correlates with a transformed phenotype in breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150:14–23. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiyer HS, Warri AM, Woode DR, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R. Influence of berry polyphenols on receptor signaling and cell-death pathways: implications for breast cancer prevention. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:5693–5708. doi: 10.1021/jf204084f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anbalagan M, Rowan BG. Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan X-Y, Sauter G, Kallioniemi O-P, Trent JM, Meltzer PS. AIB1, a Steroid Receptor Coactivator Amplified in Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Science. 1997a;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan XY, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Trent JM, Meltzer PS. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997b;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK, Schiff R. Crosstalk between the Estrogen Receptor and the HER Tyrosine Kinase Receptor Family: Molecular Mechanism and Clinical Implications for Endocrine Therapy Resistance. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29:217–233. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barletta F, Wong CW, McNally C, Komm BS, Katzenellenbogen B, Cheskis BJ. Characterization of the interactions of estrogen receptor and MNAR in the activation of cSrc. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1096–1108. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, Biogenesis, Mechanism, and Function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville S, Bartel DP. Microarray profiling of microRNAs reveals frequent coexpression with neighboring miRNAs and host genes. Rna. 2005;11:241–247. doi: 10.1261/rna.7240905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum M, Brinkley DM, Dossett JA, McPherson K, Patterson JS, Rubens RD, Smiddy FG, Stoll BA, Wilson A, Lea JC, et al. Improved survival among patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen after mastectomy for early breast cancer. Lancet. 1983;2:450. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker LE, Takwi AA, Lu Z, Li Y. The role of miR-200a in mammalian epithelial cell transformation. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:2–12. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard PL, Freedman OC, Howell A, Clemons M. Overcoming endocrine resistance in breast cancer: are signal transduction inhibitors the answer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi A, Katzenellenbogen BS. Tamoxifen downregulation of miR-451 increases 14-3-3zeta and promotes breast cancer cell survival and endocrine resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31:39–47. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi A, Madak-Erdogan Z, Kim YJ, Choi YL, Lu H, Katzenellenbogen BS. The forkhead transcription factor FOXM1 promotes endocrine resistance and invasiveness in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer by expansion of stem-like cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:436. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berillo O, Regnier M, Ivashchenko A. Binding of intronic miRNAs to the mRNAs of host genes encoding intronic miRNAs and proteins that participate in tumourigenesis. Comput Biol Med. 2013;43:1374–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. Rna. 2004;10:185–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JR, Pober JS. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) Oncogene. 2001;20:6482–6491. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braicu C, Tomuleasa C, Monroig P, Cucuianu A, Berindan-Neagoe I, Calin GA. Exosomes as divine messengers: are they the Hermes of modern molecular oncology? Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:34–45. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Ruoslahti E. Metadherin, a cell surface protein in breast tumors that mediates lung metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:365–374. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, Wicinski J, Cervera N, Finetti P, Hur MH, Diebel ME, Monville F, Dutcher J, et al. Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1302–1313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WX, Cai YQ, Lv MM, Chen L, Zhong SL, Ma TF, Zhao JH, Tang JH. Exosomes from docetaxel-resistant breast cancer cells alter chemosensitivity by delivering microRNAs. Tumour Biol. 2014a;35:9649–9659. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WX, Liu XM, Lv MM, Chen L, Zhao JH, Zhong SL, Ji MH, Hu Q, Luo Z, Wu JZ, et al. Exosomes from drug-resistant breast cancer cells transmit chemoresistance by a horizontal transfer of microRNAs. PLoS One. 2014b;9:e95240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WX, Zhong SL, Ji MH, Pan M, Hu Q, Lv MM, Luo Z, Zhao JH, Tang JH. MicroRNAs delivered by extracellular vesicles: an emerging resistance mechanism for breast cancer. Tumour Biology. 2014c;35:2883–2892. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature. 2005;436:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba M, Kimura M, Asari S. Exosomes secreted from human colorectal cancer cell lines contain mRNAs, microRNAs and natural antisense RNAs, that can transfer into the human hepatoma HepG2 and lung cancer A549 cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1551–1558. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Lui A, Ogony J, Jan R, Sims PJ, Lewis-Wambi J. Targeting interferon response genes sensitizes aromatase inhibitor resistant breast cancer cells to estrogen-induced cell death. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:6. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0506-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cittelly DM, Das PM, Salvo VA, Fonseca JP, Burow ME, Jones FE. Oncogenic HER2{Delta}16 suppresses miR-15a/16 and deregulates BCL-2 to promote endocrine resistance of breast tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2010a;31:2049–2057. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cittelly DM, Das PM, Spoelstra NS, Edgerton SM, Richer JK, Thor AD, Jones FE. Downregulation of miR-342 is associated with tamoxifen resistant breast tumors. Mol Cancer. 2010b;9:317. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GM, McGuire WL. Steroid receptors and other prognostic factors in primary breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1988;15:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GM, Osborne CK, McGuire WL. Correlations between estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and patient characteristics in human breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:1102–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Liu MC, Bouker KB, Gu Z, Lee RY, Zhu Y, Skaar TC, Gomez B, O’Brien K, Wang Y, et al. Antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer and the role of estrogen receptor signaling. Oncogene. 2003;22:7316–7339. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A, Court J, Navabi H, Adams M, Mason MD, Hobot JA, Newman GR, Jasani B. Analysis of antigen presenting cell derived exosomes, based on immuno-magnetic isolation and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2001;247:163–174. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane DR, Cittelly DM, Howe EN, Spoelstra NS, McKinsey EL, LaPara K, Elias A, Yee D, Richer JK. MicroRNAs link estrogen receptor alpha status and Dicer levels in breast cancer. Horm Cancer. 2010;1:306–319. doi: 10.1007/s12672-010-0043-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA. Relationship between estrogen levels, use of hormone replacement therapy, and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:814–823. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Sempere M, Ibanez de Caceres I. microRNAs as novel epigenetic biomarkers for human cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:357–362. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0668-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Bi M, Overstreet AM, Yang Y, Li H, Leng Y, Qian K, Huang Q, Zhang C, Lu Z, et al. MiR-873 regulates ER[alpha] transcriptional activity and tamoxifen resistance via targeting CDK3 in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF investigators AL. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Yin L, Zhang XT, Liu LJ, Wang ML, Wang ZY. ER-alpha variant ER-alpha36 mediates antiestrogen resistance in ER-positive breast cancer stem/progenitor cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144(Pt B):417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MS. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, Coates A, Forbes J, Bliss J, Buyse M, Baum M, Buzdar A, Colleoni M, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:509–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L, Ross DD. Multidrug resistance mediated by the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) Oncogene. 2003;22:7340–7358. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichelser C, Stuckrath I, Muller V, Milde-Langosch K, Wikman H, Pantel K, Schwarzenbach H. Increased serum levels of circulating exosomal microRNA-373 in receptor-negative breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2014;5:9650–9663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissa S, Matboli M, Shehata HH. Breast tissue-based microRNA panel highlights microRNA-23a and selected target genes as putative biomarkers for breast cancer. Transl Res. 2015;165:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L, Ravo M, Nassa G, Tarallo R, De Filippo MR, Giurato G, Cirillo F, Stellato C, Silvestro S, Cantarella C, et al. Effects of oestrogen on microRNA expression in hormone-responsive breast cancer cells. Horm Cancer. 2012;3:65–78. doi: 10.1007/s12672-012-0102-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Sabo E. Association of the membrane estrogen receptor, GPR30, with breast tumor metastasis and transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Steroids. 2008;73:870–873. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, Cedermark B, Glas U, Mattsson A, Silfversward C, Skoog L, Somell A, Theve T, Wilking N, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen in early breast cancer: occurrence of new primary cancers. Lancet. 1989;1:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R, Han BW, Hung JH, Xu J, Weng Z, Zamore PD. Dicer partner proteins tune the length of mature miRNAs in flies and mammals. Cell. 2012;151:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan R, Yang Y, Yang X, Zhao L, Lu J, Meng QH. Downregulation of miR-221/222 enhances sensitivity of breast cancer cells to tamoxifen through upregulation of TIMP3. Cancer Gene Ther. 2014;21:290–296. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennarino VA, Sardiello M, Avellino R, Meola N, Maselli V, Anand S, Cutillo L, Ballabio A, Banfi S. MicroRNA target prediction by expression analysis of host genes. Genome Res. 2009;19:481–490. doi: 10.1101/gr.084129.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh JN, Loo SY, Datta A, Siveen KS, Yap WN, Cai W, Shin EM, Wang C, Kim JE, Chan M, et al. microRNAs in breast cancer: regulatory roles governing the hallmarks of cancer. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1111/brv.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Jaiswal R, Mathys JM, Combes V, Grau GE, Bebawy M. Microparticles and their emerging role in cancer multidrug resistance. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardis MM, Robinson SP, Satyaswaroop PG, Jordan VC. Contrasting actions of tamoxifen on endometrial and breast tumor growth in the athymic mouse. Cancer Res. 1988;48:812–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttilla IK, Phoenix KN, Hong X, Tirnauer JS, Claffey KP, White BA. Prolonged mammosphere culture of MCF-7 cells induces an EMT and repression of the estrogen receptor by microRNAs. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1534-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman N, Agarwal K, Asthagiri D, Saji M, Ringel MD, Paulaitis ME. Breast Cancer-Specific miR Signature Unique to Extracellular Vesicles includes “microRNA-like” tRNA Fragments. Mol Cancer Res. 2015 doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, Szallasi Z. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lanczky A. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson SP, Rubinek T, Ryvo L, Wolf I. Endocrine resistance in breast cancer: focus on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. Breast Care (Basel) 2013;8:248–255. doi: 10.1159/000354757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi SI, Kimura M. Mechanisms of hormonal therapy resistance in breast cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0788-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes EL, Lewis-Wambi JS. Mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer: an overview of the proposed roles of noncoding RNA. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:40. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0542-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YJ, Wu JZ, Ji MH, Ma T, Qiao EQ, Ma R, Tang JH. miR-342 is associated with estrogen receptor-alpha expression and response to tamoxifen in breast cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:813–818. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herynk MH, Fuqua SA. Estrogen receptor mutations in human disease. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:869–898. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]