Abstract

Objective

The Lumbee Indian tribe is the largest Native American tribe in North Carolina, with about 55,000 enrolled members who mostly reside in southeastern counties. We evaluated whether Lumbee heritage is associated with high-risk histologic subtypes of endometrial cancer.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the available records from IRB-approved endometrial cancer databases at two institutions of patients of Lumbee descent (year of diagnosis range 1980–2014). Each Lumbee case was matched by age, year of diagnosis, and BMI to two non-Lumbee controls. Chi-square test was used to compare categorical associations. Kaplan–Meier methods and log-rank test were used to display and compare disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to adjust for age and BMI while testing cohort as a predictor of DFS and OS.

Results

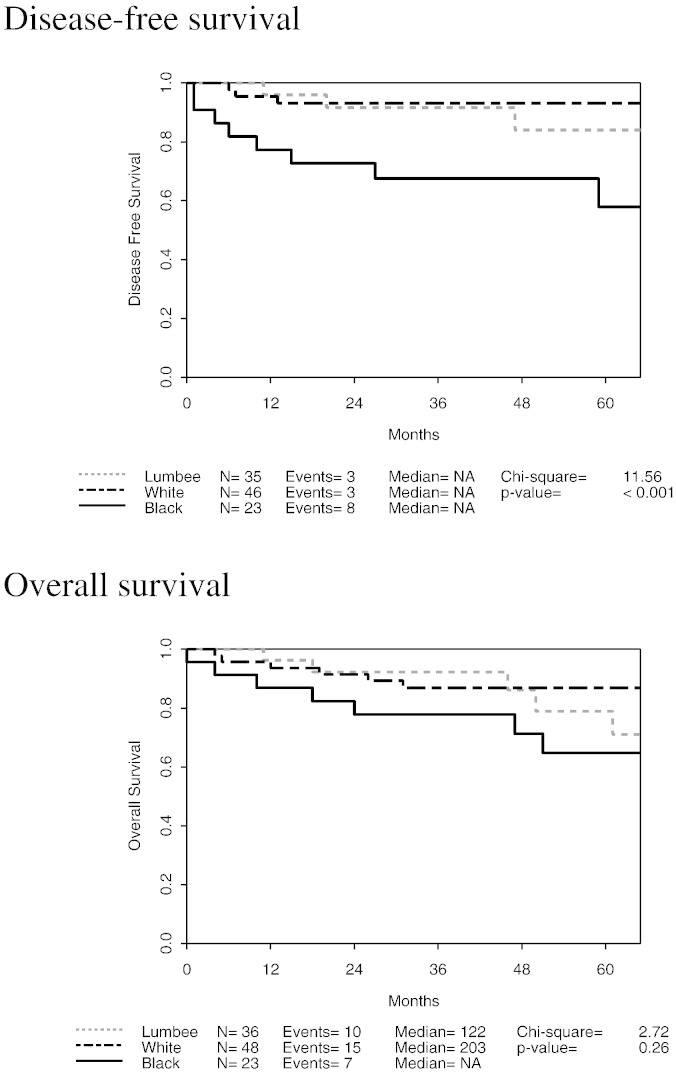

Among 108 subjects, 10/35 (29%) Lumbee and 19/72 (26%) non-Lumbee subjects had high-risk (serous/clear cell/carcinosarcoma) histologic types (p = 0.8). 12/35 (34%) Lumbee and 24/72 (33%) non-Lumbee subjects had grade 3 tumors (p = 0.9). 5/33 (15%) Lumbee and 13/72 (18%) non-Lumbee had advanced stage endometrial cancer at diagnosis (p = 0.7). Lumbee ancestry was not associated with worse survival outcomes. OS (p = 0.054) and DFS (p = 0.01) were both worse in Blacks compared to Lumbee and White subjects.

Conclusion

In this retrospective cohort analysis, Lumbee Native American ancestry was not a significant independent predictor of rates of high-risk histological subtypes of endometrial cancer or poor survival outcomes.

Keywords: Lumbee Indian tribe, Survival outcomes, Endometrial cancer

Highlights

-

•

In a retrospective cohort study, women with endometrial cancer of Lumbee Native American ancestry were matched to non-Native American controls.

-

•

Women with Native American ancestry did not have a significantly higher incidence of high-risk histologic type when compared to controls.

-

•

Disease-free survival and overall survival were lower in Black subjects compared to White and Native American subjects.

1. Introduction

The Lumbee Indian tribe, with 55,000 enrolled members, is the largest Native American tribe in North Carolina. Between 1975 and 1997, Native Americans compared to all other races had the highest relative risk of death from cancer for all cancers except for colorectal cancer in males (Clegg et al., 2002). From 1992 to 2000, even after adjusting for the census tract poverty rate, Native American women had lower five-year survival than did non-Hispanic Whites for all cancers combined (Ward et al., 2004). During 2000–2009, while all non-Native American racial/ethnic groups experienced at least a 1.1% decline in cancer death rates per year, Native Americans experienced no decline in cancer death rates (Siegel et al., 2013).

Disparities in factors linked to both socioeconomic status and cancer prevention and screening practices have been observed in Native Americans compared to other races in the U.S. Compared to Whites, Native Americans have lower educational status, less access to health care coverage or a source of primary care, and higher poverty rates (Ward et al., 2004). In a study conducted in Arizona, Native Americans were more likely than Whites to travel greater than 50 miles for endometrial cancer surgery and faced greater barriers to care by a gynecologic oncologist (Benjamin et al., 2011). In rural Robeson County, North Carolina, Native American women, as compared to White and Black women, have the lowest levels of education, least insurance coverage, and least accurate knowledge regarding breast carcinoma (Paskett et al., 2004).

However, no direct link between cancer prognosis or survival and culture or SES specific to the Lumbee population has been established. Given the paucity of scientific literature on endometrial cancer in the Lumbee population, we sought to evaluate whether, among patients referred to our institutions, Lumbee heritage is associated with an elevated risk for histologic subtypes of endometrial cancer that carry a worse prognosis.

2. Methods

Following Institutional Review Board approval of retrospectively collected endometrial cancer databases at each institution, we identified Lumbee women with endometrial cancer who were referred for treatment at Duke University Medical Center (Duke) or the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Hospitals (UNC) between 1980 and 2014. We developed four Lumbee identification criteria, of which two were required for entry into the Lumbee cohort (cases): (1) Subject has one of the 23 traditional Lumbee last names (Barnes, Bell, Braveboy, Brayboy, Brooks, Bullard, Chavers, Chavis, Cumbo, Cummings, Hammonds, Hunt, Jacobs, Lockileer, Locklear, Lowerie, Lowry, Lowery, Oxendine, Revils, Revels, Strickland, Wilkins); (2) subject is a resident of Robeson County, NC, 38% of whose citizens are members of the Lumbee tribe; (3) subject is identified as Native American/American Indian in medical record; and (4) subject is identified specifically as Lumbee in medical record.

Each Lumbee case was matched to two non-Lumbee controls. Cases and controls were matched by age at diagnosis, institution of diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), and date of surgery. Matched controls were selected randomly if more than one possible control was found. Medical records were reviewed to abstract data on age, BMI, race, ethnicity, insurance status, hypertension, arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, type of hysterectomy, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage based on the 2009 staging system, histology, grade, depth of myometrial invasion, myometrial thickness, tumor size, cervix invasion, fallopian tube and ovarian involvement, performance of lymph node dissection, lymph vascular space invasion (LVSI), pelvic peritoneal cytology, adjuvant therapy received, recurrence, and overall survival (OS). Assessment of ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic, other) was attempted but information was not available on medical records from Duke University Medical Center.

The Chi-square test was used to compare cases to controls on histologic type (containing serous, clear cell, or carcinosarcoma components vs. none of these components), FIGO grade (grade 3 vs. grades 1–2), and “high-risk cancer”, defined as the presence of papillary serous, clear cell, or carcinosarcoma histology or FIGO grade 3. Chi-squared test was also performed to compare cases to controls on clinical and pathological characteristics. Characteristics examined included insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid, none), hypertension (yes vs. no), cardiovascular diseases, diabetes (yes vs. no), smoking history (yes vs. no), type of hysterectomy (minimally invasive hysterectomy vs. total abdominal hysterectomy), cervix invasion (negative, involvement of glandular epithelium or stromal invasion), number of positive pelvic nodes (0 vs. 1 or more), fallopian tube and ovarian involvement (positive vs. negative), LVSI (positive vs. negative), pelvic peritoneal cytology (positive, negative, atypical), adjuvant chemotherapy (yes vs. no), adjuvant radiation (yes vs. no) and recurrence (yes vs. no). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare central tendencies of continuous variables in the three race cohorts. Variables were considered significant at p < 0.05. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as time from date of surgery until first relapse or death of endometrial cancer; for patients still alive without relapse it was censored at the last follow-up visit or death due to other causes. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as time from date of surgery until death of any cause, and was censored at the last follow-up date for those still alive. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards multivariate regression models were used to determine if race cohort predicts OS and DFS while adjusting for age and BMI. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS v. 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and survival plots were created using Spotfire S + v. 8.1 (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA).

3. Results

One hundred eight patients (36 Lumbee, 72 non-Lumbee) were included in this study. Of the 36 Lumbee subjects who met at least two out of the four Lumbee identification criteria, 34 subjects had one of the 23 traditional Lumbee last names; 35 subjects were residents of Robeson County; 34 subjects were identified as Native American/American Indian in medical record; and 3 subjects were identified specifically as Lumbee in medical record.

Table 1 describes the pre-operative characteristics of each cohort. The mean age at diagnosis was 61 and the mean BMI was 36. Median year of diagnosis was 2006. There were no significant differences between cohorts in age, BMI, year of surgery, smoking status, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Among subjects with known insurance status, 4/26 (15%) Lumbee, 15/32 (47%) White and 10/23 (44%) Black subjects had private insurance (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Pre-operative characteristics of 3 cohorts.

| Characteristics | Lumbee |

Whites |

Blacks |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 36 | n = 49 | n = 23 | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 62.2 (11.8) | 64 (13.4) | 58 (13.2) | 0.09 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 37.5 (12.1) | 35.5 (12.8) | 37.7 (13.0) | 0.9 |

| Surgical year, median (IQR) | 2006.5 (4.5) | 2005 (14.0) | 2008 (3.0) | 0.1 |

| Smoker, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 5 (15%) | 7 (16%) | 4 (18%) | 0.9 |

| No | 29 (85%) | 37 (84%) | 18 (82%) | |

| Not reported | 2 | 5 | 1 | |

| Cardiovascular diseases, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 5 (14%) | 10 (21%) | 4 (17%) | 0.7 |

| No | 31 (86%) | 37 (79%) | 19 (83%) | |

| Not reported | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Diabetic, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 12 (33%) | 12 (25%) | 8 (35%) | 0.6 |

| No | 24 (67%) | 36 (75%) | 15 (65%) | |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Hypertension, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 25 (69%) | 32 (67%) | 14 (61%) | 0.8 |

| No | 11 (31%) | 16 (33%) | 9 (39%) | |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Insurance status, number (%) | ||||

| Private insurance | 4 (11%) | 15 (31%) | 10 (43%) | 0.03 |

| Medicare | 14 (39%) | 15 (31%) | 10 (43%) | |

| Medicaid | 5 (14%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (9%) | |

| No insurance | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 10 (28%) | 17 (34%) | 0 (0%) | |

Note. IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2a, Table 2b describe the operative results and outcomes of each cohort. High-risk cancer (either grade 3 or histological types of serous, clear cell, or carcinosarcoma) was found in 13/35 (37%) Lumbee, 15/49 (31%) White and 12/23 (52%) Black subjects (p = 0.2). High-grade (grade 3 vs. grades 1–2) tumors were found in 12/35 (34%) Lumbee, 12/49 (24%) White and 12/23 (52%) Black subjects (p = 0.2). Tumors containing high-risk histologic types (serous/clear cell/carcinosarcoma) were found in 10/35 (29%) Lumbee, 9/49 (18%) White, and 10/23 (43%) Black subjects (p = 0.08). Advanced stage (stages III–IV) endometrial cancer at diagnosis was found in 5/33 (15%) Lumbee, 6/49 (12%) White, and 7/23 (30%) Black subjects (p = 0.15). The number of pelvic lymph nodes removed was similar between groups; there was a trend toward removal of more aortic lymph nodes in black subjects (median number in Lumbee 3; White 0; Black 5.5; p = 0.053). Rates of receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy were not significantly different between cohorts.

Table 2a.

Operative results and outcomes of 3 cohorts.

| Operative results | Lumbee |

Whites |

Blacks |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 36 | n = 49 | n = 23 | ||

| FIGO grade, number (%) | ||||

| 1 | 12 (34%) | 20 (41%) | 6 (26%) | 0.2 |

| 2 | 11 (32%) | 17 (35%) | 5 (22%) | |

| 3 | 12 (34%) | 12 (24%) | 12 (52%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Histologic type, number (%) | ||||

| Endometrioid | 24 (68.6%) | 34 (69.4%) | 12 (52.2%) | |

| Papillary serous | 5 (14.3%) | 3 (6.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Clear cell | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (4.4%) | |

| Mucinous | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (2.8%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Mixed without clear cell or serous | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (4.4%) | |

| Mixed with clear cell or serous | 3 (8.6%) | 4 (8.2%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| Carcinosarcoma | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| High-risk histologic type, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10 (29%) | 9 (18%) | 10 (43%) | 0.08 |

| No | 25 (71%) | 40 (82%) | 13 (57%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| High-risk cancer⁎, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13 (37%) | 15 (31%) | 12 (52%) | 0.2 |

| No | 22 (63%) | 34 (69%) | 11 (48%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| FIGO stage, number (%) | ||||

| I–II | 28 (85%) | 43 (88%) | 16 (70%) | 0.15 |

| III–IV | 5 (15%) | 6 (12%) | 7 (30%) | |

| Not reported | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| # pelvic nodes removed, median (IQR) | 11.5 (11.5) | 13.0 (15.0) | 15.0 (10.0) | 0.3 |

| # aortic nodes removed, median (IQR) | 3.0 (6.0) | 0.0 (7.0) | 5.5 (8.0) | 0.053 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 6 (19%) | 9 (18%) | 9 (43%) | 0.06 |

| No | 26 (81%) | 40 (82%) | 12 (57%) | |

| Not reported | 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13 (41%) | 11 (22%) | 8 (38%) | 0.2 |

| No | 19 (59%) | 38 (78%) | 13 (62%) | |

| Not reported | 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Recurrence, number (%) | ||||

| Yes | 4 (12%) | 5 (10%) | 6 (27%) | 0.15 |

| No | 29 (88%) | 44 (90%) | 16 (73%) | |

| Not reported | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

Note. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

High risk cancer = papillary serous, grade 3, carcinosarcoma, or FIGO grade 3.

Table 2b.

Operative results and outcomes of 2 cohorts (Lumbee vs. controls).

| Operative results | Lumbee |

Non-Lumbee |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 36 | n = 72 | ||

| FIGO grade, number (%) | |||

| 1 | 12 (34%) | 26 (36%) | 1.0 |

| 2 | 11 (32%) | 22 (31%) | |

| 3 | 12 (34%) | 24 (33%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | |

| Histologic type, number (%) | |||

| Endometrioid | 24 (68.6%) | 46 (63.9%) | |

| Papillary serous | 5 (14.3%) | 5 (6.9%) | |

| Clear cell | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Mucinous | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (2.8%) | 4 (5.6%) | |

| Mixed without clear cell or serous | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Mixed with clear cell or serous | 3 (8.6%) | 9 (12.5%) | |

| Carcinosarcoma | 1 (2.8%) | 3 (4.2%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | |

| High-risk histologic types, number (%) | |||

| Yes | 10 (29%) | 19 (26%) | 0.8 |

| No | 25 (71%) | 53 (74%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | |

| High-risk cancer⁎, number (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (37%) | 27 (38%) | 1.0 |

| No | 22 (63%) | 45 (62%) | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | |

| FIGO stage, number (%) | |||

| I–II | 28 (85%) | 59 (82%) | 0.7 |

| III–IV | 5 (15%) | 13 (18%) | |

| Not reported | 3 | 0 | |

| # pelvic nodes removed, median (IQR) | 11.5 (11.5) | 13.0 (15.0) | 0.5 |

| # aortic nodes removed, median (IQR) | 3.0 (6.0) | 3.0 (8.0) | 0.6 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, number (%) | |||

| Yes | 6 (19%) | 18 (26%) | 0.4 |

| No | 26 (81%) | 52 (74%) | |

| Not reported | 4 | 2 | |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy, number (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (41%) | 19 (27%) | 0.2 |

| No | 19 (59%) | 51 (73%) | |

| Not reported | 4 | 2 | |

| Recurrence, number (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (12%) | 11 (15%) | 0.6 |

| No | 29 (88%) | 60 (85%) | |

| Not reported | 3 | 1 | |

Note. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

High risk cancer = papillary serous, grade 3, carcinosarcoma, or FIGO grade 3.

The endometrial cancer recurrence rate was 10% for White, 12% for Lumbee, and 27% for Black subjects (p = 0.15). Fig. 1 depicts Kaplan–Meier curves for DFS and OS. The 5-year DFS rates were 84% (68–100%) for Lumbee, 93% (86–100%) for White, and 58% (39–88%) for Black subjects (univariate p < 0.001). In a multivariate Cox regression model to predict DFS while adjusting for age and BMI, race was a significant predictor (p = 0.01), with Black subjects having significantly shorter DFS than White or Lumbee subjects. The 5-year OS rates were 79% (62–100%) for Lumbee, 87% (78–97%) for White, and 65% (46–91%) for Black subjects (univariate p = 0.26). In a multivariate Cox regression model to predict OS while adjusting for age and BMI, race cohort was a borderline significant predictor (p = 0.054).

Fig. 1.

Disease-free and overall survival.

4. Discussion

In this matched retrospective cohort study of women with endometrial cancer treated at two academic institutions in North Carolina, we examined the prevalence of biologically aggressive subtypes of endometrial cancer between Lumbee and non-Lumbee patients. We found no significant difference between cohorts in the prevalence of high-risk histologic subtypes, high-grade (FIGO grade > 2), or advanced stage (stage III-IV) endometrial cancer. However there was a non-significant trend toward a difference in both high grade (p = 0.07) and high-risk histology (p = 0.08) when all 3 cohorts were compared, with Lumbees having a frequency of high-risk cancers between that of Whites and Blacks. Prior studies have demonstrated that Blacks have a higher rate of high-risk endometrial cancer subtypes and a poorer prognosis than Whites (Cote et al., 2012a, Cote et al., 2012b, Sherman and Devesa, 2003, Maxwell et al., 2006, Santin et al., 2005a, Santin et al., 2005b, Setiawan et al., 2007, Ueda et al., 2008). While we did not demonstrate poor cancer outcomes in the Lumbee cohort, the small size of our study likely limits our ability to assess this.

One compelling reason to investigate racial disparities in cancer characteristics and outcomes is the issue of access to care, which can differ significantly along racial lines in many cancers. For example, several recent studies have demonstrated differences in receipt of standard ovarian cancer treatments between Blacks and Whites, with a corresponding difference in survival outcomes (Terplan et al., 2009, Bristow et al., 2013). Rather than a biologic or molecular cause, unequal application of treatment appeared to account for the differences in outcomes. The socioeconomic disparities and knowledge deficits about certain cancers seen in the general Native Americans population have also been observed in the Lumbee (Paskett et al., 2004). The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is a unique group of Native Americans, alternately speculated to have descended from an admixture of seven Native American tribes in the South Eastern U.S., the Lost Colonists who settled in coastal North Carolina in the 1580s, and those of European and African American ancestry (McMillan, 1888, Pollitzer, 1972, Anon, 2012). It is currently unknown how certain genetic features of this culturally and ancestrally distinct population may influence cancer risks and mortality.

Limitations of this study include the lack of any official guidelines to identify Lumbee subjects. Our Lumbee identification criteria are not validated and may be overly restrictive; those who married outside of the Lumbee community and lost their traditional last names may not have been identified as Lumbee. Lumbee women may also have been misidentified or not identified racially in medical records. In fact, only 3 of the 36 Lumbee subjects in our study were specifically identified as Lumbee in their medical records. Historically, identification of Native Americans has been challenging and often inaccurate. For example, comparison of self-identified race from listed by the U.S. Census Bureau to state death records shows that 41% of Native Americans are recorded as non-native when someone else assigns their race (Espey et al., 2005). Other limitations include the small sample size, which limits the power to detect significant differences between cohorts. Finally, Lumbee subjects in our study sample may not be representative of all Lumbee, as women with the lowest risk cancers may have undergone hysterectomy closer to home than our institutions.

More work is needed to clarify the extent to which Lumbee heritage may contribute to endometrial cancer risk and outcomes. This population may benefit from increased education on endometrial cancer detection and risk reduction strategies, such as interventions to target obesity, a major risk factor. Better access to gynecologic oncology care through new and established referral pathways may also be a starting point in lowering barriers to care for the large Lumbee population in southeastern North Carolina.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Anon . U.S. G.P.O.; Washington, D.C.: 2012. Providing for the recognition of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, and for other purposes report together with additional views (to accompany S. 1218) [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin I., Dalton H., Qiu Y., Cayco L., Johnson W.G., Balducci J. Endometrial cancer surgery in Arizona: a statewide analysis of access to care. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011;121(1):83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow R.E., Powell M.A., Al-Hammadi N., Chen L., Miller J.P., Roland P.Y., Mutch D.G., Cliby W.A. Disparities in ovarian cancer care quality and survival according to race and socioeconomic status. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):823–832. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg L.X., Li F.P., Hankey B.F., Chu K., Edwards B.K. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Program population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162(17):1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote M.L., Atikukke G., Ruterbusch J.J., Olson S.H., Sealy-Jefferson S., Rybicki B.A., Alford S.H., Elshaikh M.A., Gaba A.R., Schultz D. Racial differences in oncogene mutations detected in early-stage low-grade endometrial cancers. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2012;22(8):1367–1372. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31826b1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote M.L., Kam A., Chang C.Y.-Y., Raskin L., Reding K.W., Cho K.R., Gruber S.B., Ali-Fehmi R. A pilot study of microsatellite instability and endometrial cancer survival in White and African American women. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2012;31(1):66–72. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318224329e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espey D., Paisano R., Cobb N. Regional patterns and trends in cancer mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2001. Cancer. 2005;103(5):1045–1053. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell G.L., Tian C., Risinger J., Brown C.L., Rose G.S., Thigpen J.T., Fleming G.F., Gallion H.H., Brewster W.R. Racial disparity in survival among patients with advanced/recurrent endometrial adenocarcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2197–2205. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan H. Indicating the Fate of the Colony of Englishmen Left on Roanoke Island in 1587. vol. 210. Advance Presses; 1888. Sir Walter Raleigh's lost colony: a historical sketch of the attempts of Sir Walter Raleigh to establish a colony in Virginia, with the traditions of an Indian Tribe in North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Paskett E.D., Tatum C., Rushing J., Michielutte R., Bell R., Foley K.L., Bittoni M., Dickinson S. Racial differences in knowledge, attitudes, and cancer screening practices among a triracial rural population. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2650–2659. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollitzer W.S. The physical anthropology and genetics of marginal people of the Southeastern United States. Am. Anthropol. 1972;74(3):719–734. [Google Scholar]

- Santin A.D., Bellone S., Siegel E.R., Palmieri M., Thomas M., Cannon M.J., Kay H.H., Roman J.J., Burnett A., Pecorelli S. Racial differences in the overexpression of epidermal growth factor type II receptor (HER2/neu): a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;192(3):813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santin A.D., Bellone S., Van Stedum S., Bushen W., Palmieri M., Siegel E.R., De Las Casas L.E., Roman J.J., Burnett A., Pecorelli S. Amplification of c-erbB2 oncogene: a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(7):1391–1397. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan V.W., Pike M.C., Kolonel L.N., Nomura A.M., Goodman M.T., Henderson B.E. Racial/ethnic differences in endometrial cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;165(3):262–270. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M.E., Devesa S.S. Analysis of racial differences in incidence, survival, and mortality for malignant tumors of the uterine corpus. Cancer. 2003;98(1):176–186. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R., Naishadham D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terplan M., Smith E.J., Temkin S.M. Race in ovarian cancer treatment and survival: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(7):1139–1150. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda S.M., Kapp D.S., Cheung M.K., Shin J.Y., Osann K., Husain A., Teng N.N., Berek J.S., Chan J.K. Trends in demographic and clinical characteristics in women diagnosed with corpus cancer and their potential impact on the increasing number of deaths. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;198(2):218.e211–218.e216. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E., Jemal A., Cokkinides V., Singh G.K., Cardinez C., Ghafoor A., Thun M. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]