Abstract

Bone formation during fracture repair inevitably initiates within or around extravascular deposits of a fibrin-rich matrix. In addition to a central role in hemostasis, fibrin is thought to enhance bone repair by supporting inflammatory and mesenchymal progenitor egress into the zone of injury. However, given that a failure of efficient fibrin clearance can impede normal wound repair, the precise contribution of fibrin to bone fracture repair, whether supportive or detrimental, is unknown. Here, we employed mice with genetically and pharmacologically imposed deficits in the fibrin precursor fibrinogen and fibrin-degrading plasminogen to explore the hypothesis that fibrin is vital to the initiation of fracture repair, but impaired fibrin clearance results in derangements in bone fracture repair. In contrast to our hypothesis, fibrin was entirely dispensable for long-bone fracture repair, as healing fractures in fibrinogen-deficient mice were indistinguishable from those in control animals. However, failure to clear fibrin from the fracture site in plasminogen-deficient mice severely impaired fracture vascularization, precluded bone union, and resulted in robust heterotopic ossification. Pharmacological fibrinogen depletion in plasminogen-deficient animals restored a normal pattern of fracture repair and substantially limited heterotopic ossification. Fibrin is therefore not essential for fracture repair, but inefficient fibrinolysis decreases endochondral angiogenesis and ossification, thereby inhibiting fracture repair.

Introduction

Mechanistically, fracture repair occurs through both intramembranous and endochondral ossification, the same biological processes that occur in bone development (1, 2). However, in contrast to bone development, bone formation during fracture repair initiates within a vastly different microenvironment that develops secondary to tissue injury and hemorrhage. As a result, fracture healing inevitably initiates within or around extravascular fibrin deposits that are distributed throughout the injury. Previous studies have suggested that intrinsic elements of the fibrin matrix are essential for initiating bone formation (3). Proposed molecular mechanisms include the following: (a) acting as a reservoir for growth factors and vasoactive molecules from platelets (4–6), (b) promoting influx of inflammatory and mesenchymal progenitor cells through specific integrin/receptor interactions, and (c) providing the structural framework for the initial phase of tissue repair (3, 7). Thus, the fibrin matrices that form after fracture are considered a vital component of fracture repair. Indeed, most fracture-care protocols emphasize the importance of preserving the fracture hematoma, specifically the fibrin matrix (3, 8). Conversely, persistent fibrin deposition or a failure of efficient fibrin clearance from wound fields due to pathologic alterations in hemostasis is detrimental to normal tissue repair (9–11). Additionally, we recently determined that persistent fibrin is a driver of pathologic bone disease (12). Thus, the contribution of fibrin to fracture repair could be both supportive and detrimental.

Over 16 million fractures are treated in the United States annually (13). Impaired fracture repair, manifesting as delayed or nonunion, which occurs in between 2.5% and 10% of these cases, (14–16) results in pain and loss of function and imposes a substantial cost burden on the health care system (13). The most common comorbidities associated with impaired fracture repair are obesity, diabetes, smoking, and advanced age (17–23). Furthermore, these comorbidities are all associated with impaired fibrin clearance or fibrinolytic activity (24–26). Given that impaired fibrinolysis is a feature common to comorbidites associated with impaired fracture repair, we hypothesize that, although extravascular fibrin matrices may exert beneficial effects on fracture repair, persistent fibrin deposition may have deleterious effects on fracture repair. In this study, we investigated whether fibrin is essential for efficient fracture repair and whether persistent fibrin matrices ultimately impede normal fracture repair.

Results

Fibrin deposition is required for efficient hemostasis following bone fracture, but is not essential for fracture repair.

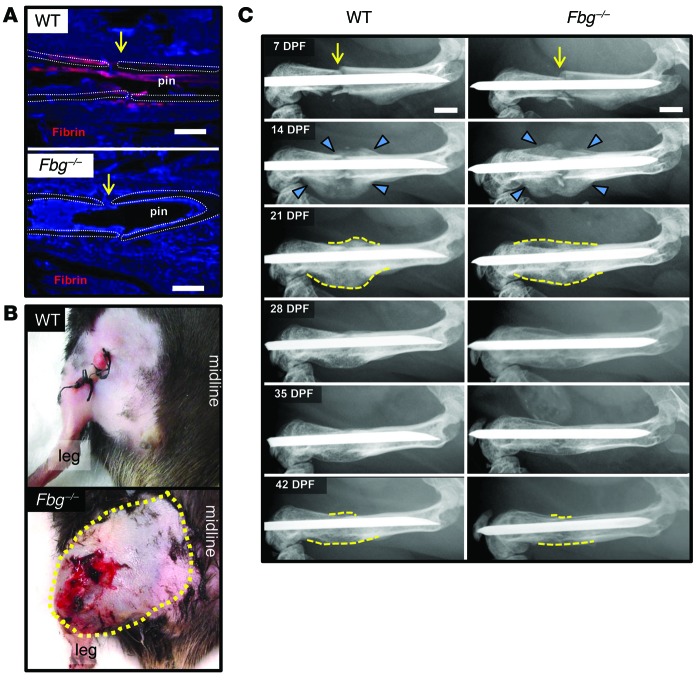

In order to define the potential roles of fibrin in fracture repair, we first characterized the temporal and spatial patterns of fibrin deposition relative to the key biologic events of fracture repair: angiogenesis and the development of a soft- and hard-tissue callus (1). Histological analyses indicated that fibrin is formed at the site of fracture shortly after injury, but is rapidly cleared during the process of intramembranous and endochondral bone formation and is no longer present at the fracture site by the time of vascular and osseous union (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1; supplemental material available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI80313DS1). To determine whether fibrin is essential for fracture repair, we examined mice lacking fibrinogen (Fbg–/–), the precursor of fibrin, during repair of a femoral fracture. As expected, Fbg–/– mice hemorrhaged excessively (Figure 1B) and no fibrin was observed at the fracture site (Figure 1A). In contrast, WT mice had no overt evidence of hemorrhage (Figure 1B) and abundant fibrin deposition was observed within the fracture site (Figure 1A). Serial radiographs of fractured femurs were performed to monitor the temporal development and subsequent remodeling of the hard-tissue callus back within the prefracture cortical bone architecture (Figure 1C). Hard-tissue callus was clearly evident proximal and distal to the fracture site in both WT and Fbg–/– mice at 14 days post fracture (DPF). During 14 to 21 DPF, the proximal and distal hard-tissue calluses converged toward the fracture site and eventually formed a bridging callus that represents the maximum size of the hard-tissue callus. Over the following 3 weeks, the hard-tissue callus condensed and became hardly discernible, approximating the original unfractured bone by 42 DPF (Figure 1C). To determine whether the absence of fibrin affected fracture callus strength, we performed finite element analysis (FEA) using microcomputed tomography (μCT) scans of the fracture site for WT and Fbg–/– mice. In this analysis, the predicted fracture callus strength did not differ between WT and Fbg–/– mice (Supplemental Figure 2). Thus, Fbg–/– mice show no temporal or quantitative differences in the development or subsequent remodeling of the hard-tissue callus, demonstrating that fibrin, although instrumental in limiting hemorrhage, is unnecessary for efficient fracture repair.

Figure 1. Fibrin is essential for limiting hemorrhage, but not for fracture callus formation.

(A) Immunofluorescence-based detection of fibrin (red) at fracture site (yellow arrow) in WT and fibrinogen-deficient (Fbg–/–) mice. Note that fibrin was prominent in WT mice proximal to the fracture site (approximate location of the femora cortical bone outlined with white dotted lines), whereas fibrin was completely absent in Fbg–/– animals at 1 DPF. (B) Gross photographs of WT and Fbg–/– mouse extremities at 1 DPF showing local excessive bleeding and hematoma formation in Fbg–/– mice (outlined by yellow dashes) compared with WT mice. (C) Temporal radiographic analysis of fractured femurs (yellow arrows) in WT and Fbg–/– mice. Note that the formation (blue arrowheads) of the fracture callus and macroscopic hard-tissue callus remodeling (dashed yellow lines) of the fracture callus were effectively indistinguishable in WT and Fbg–/– mice. n ≥ 10 for each genotype. Scale bars: 1 mm.

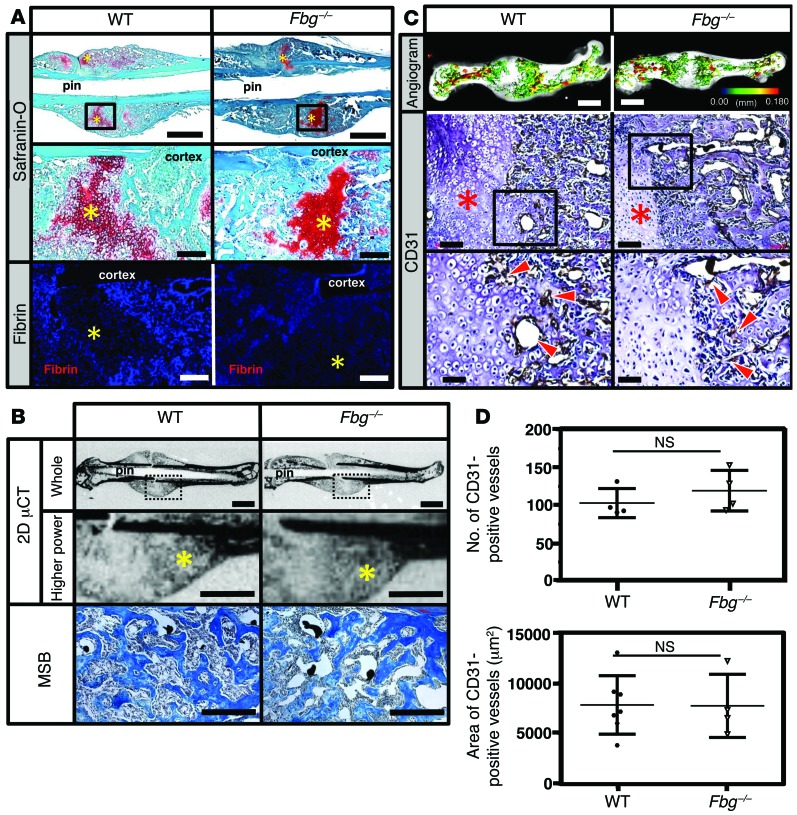

Given that the presence of fibrin is not required for fracture repair, we asked whether critical biological steps during fracture repair were altered in the absence of fibrin. Histological evaluation of fracture callus at 14 DPF revealed a centrally located, avascular chondroid matrix (soft-tissue callus) in both WT and Fbg–/– mice (Figure 2A) flanked by reactive hypercellular woven bone, indicative of early bone formation during fracture repair (Figure 2B). Quantitative assessment of the soft- and hard-tissue calluses showed no significant difference between genotypes (Table 1). To determine whether fibrin is essential for vascularization of fracture callus, angiography and immunohistochemistry for CD31 were performed. Angiography of fracture calluses at 14 DPF revealed exuberant endochondral-mediated vascularization both proximal and distal to the fractures in both WT and Fbg–/– mice (Figure 2C). CD31 staining revealed numerous vessels at the interface of the hard- and soft-tissue callus in both genotypes (Figure 2C), and quantification of vascularity showed no difference in either the vascular area or the number of vessels within the facture callus of WT or Fbg–/– mice at 14 DPF (Figure 2D). Collectively, while we cannot exclude the possibility that subtle details of the reparative process were modified by the loss of fibrin, these data demonstrate that fibrin is not required for either endochondral bone formation or vascularization of the fracture callus.

Figure 2. Fibrin is not essential for soft-tissue callus formation and vascularization of fracture callus.

(A) WT and Fbg–/– mice stained with safranin O or immunofluorescence for fibrin at 14 DPF. Other than the distinct absence of local fibrin deposition in Fbg–/– mice, no obvious differences were detected in fracture callus formation (chondroid soft-tissue callus, yellow asterisks). Scale bars: 1 mm (top panels); 100 μm (middle and bottom panels). n ≥ 5 for each genotype. (B) 2D μCT images of mineralized bone (yellow asterisks) and MSB-stained histologic sections of tissues in WT and Fbg–/– mice. Note that regardless of fibrinogen status, these areas contain reactive hypercellular trabecular woven bone. Scale bars: 1 mm (whole, μCT); 500 μm (higher power, μCT); 100 μm (MSB). (C) Comparative analyses of vasculature in WT and Fbg–/– mice. Note that both 3D μCT reconstructions of contrast-perfused femurs and immunofluorescence for CD31 revealed no clear differences in the macro- and microvasculature of the fracture callus at 14 DPF in WT and Fbg–/– mice (soft-tissue callus, red asterisks; CD31-positive vessels, red arrowheads). Scale bars: 1 mm (top panels); 100 μm (middle panels); 50 μm (bottom panels). n ≥ 4 for each genotype. In the angiographic images, the color scale bar denotes vessel size: black (0.00 mm); red (0.18 mm). Black boxes denote areas shown at higher magnification. (D) Quantitative analysis of CD31-positive blood vessels in the callus in tissue sections. No significant differences (Student’s t test) were observed in the either the number (top) or total area of CD31-positive blood vessels (bottom). n ≥ 4 for each genotype. Four sections in each sample were averaged to constitute a single replicate (1 n). Error bars indicate SD.

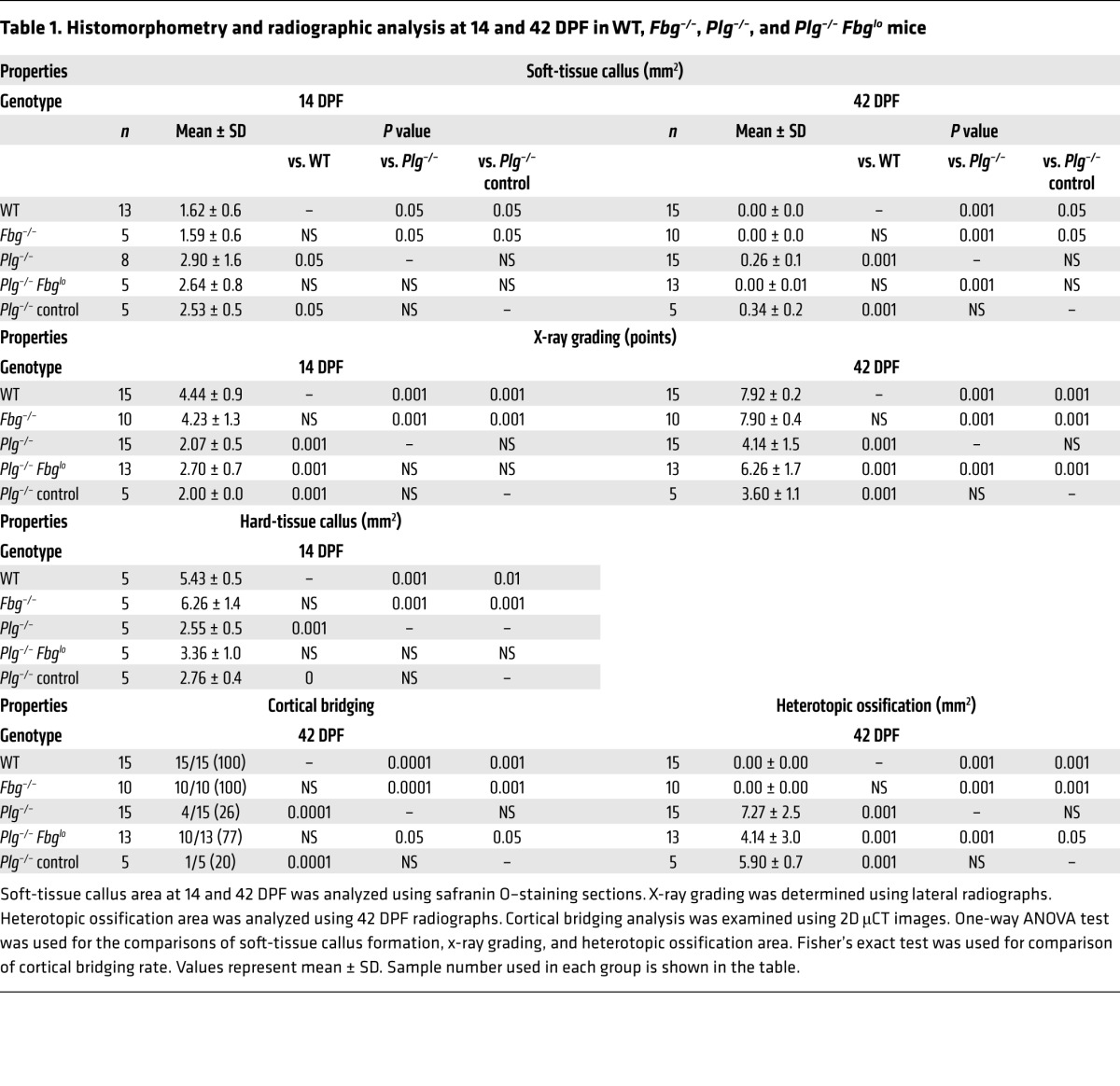

Table 1. Histomorphometry and radiographic analysis at 14 and 42 DPF in WT, Fbg–/–, Plg–/–, and Plg–/– Fbglo mice.

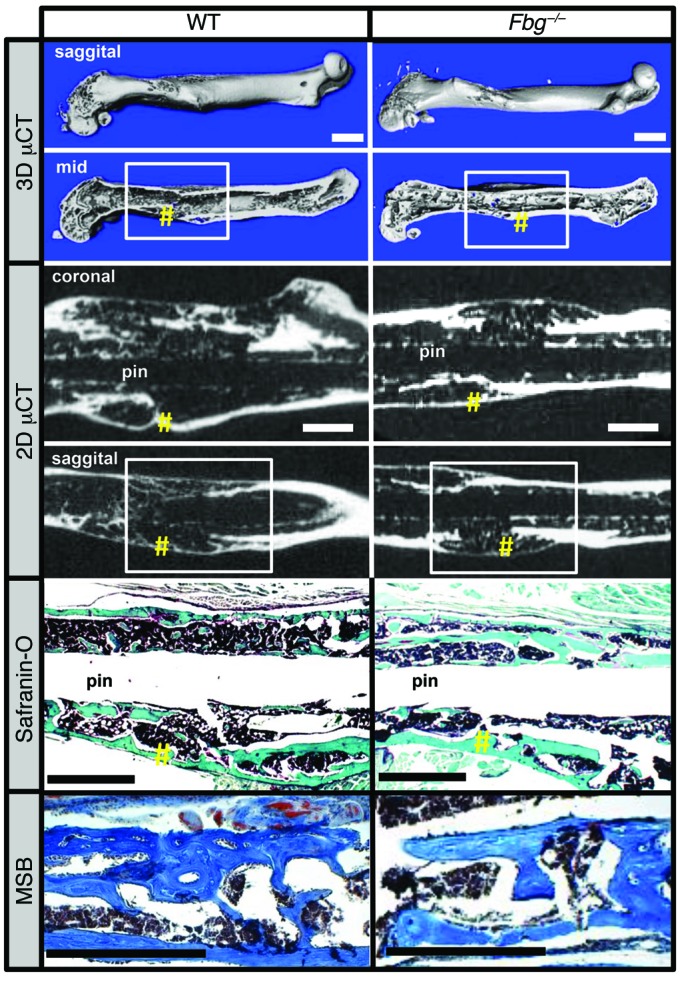

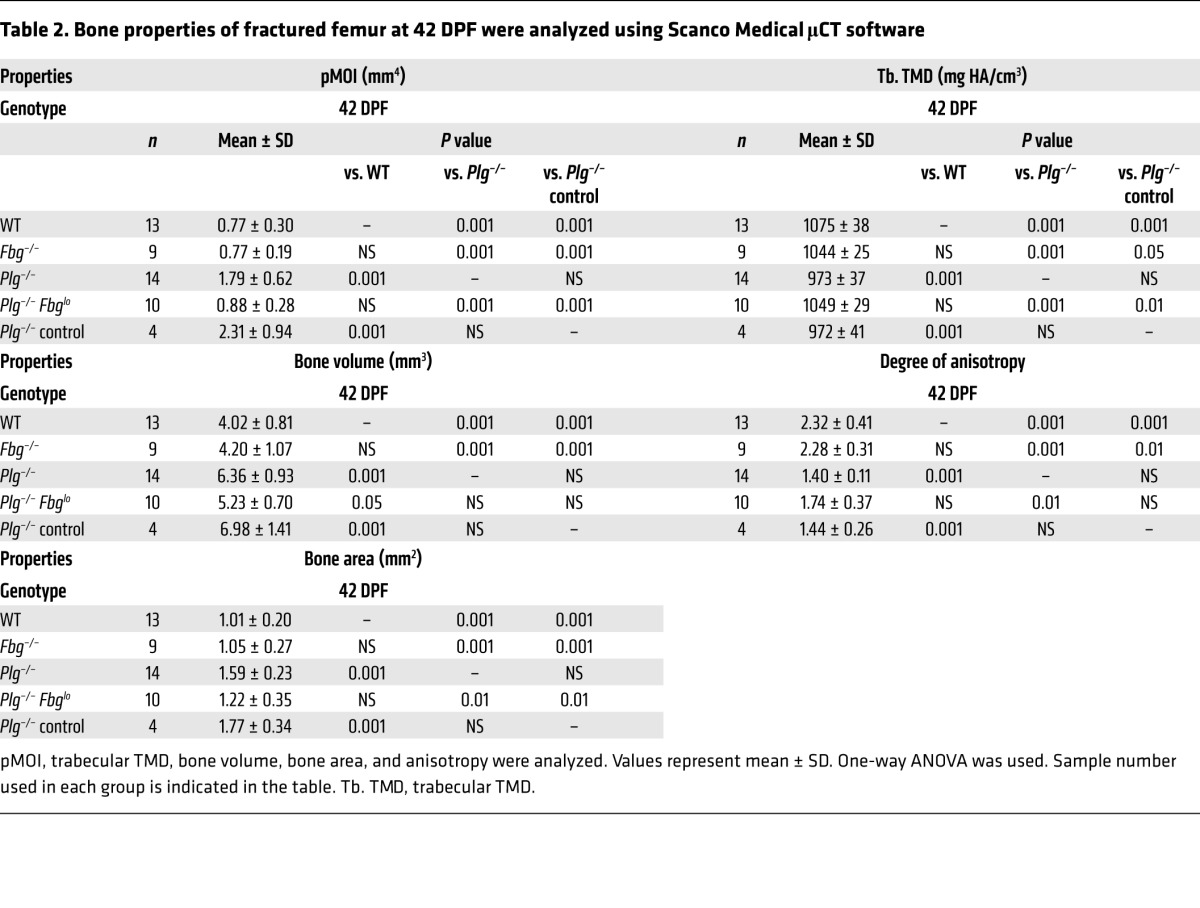

To determine whether fibrin has an effect on the union of the hard-tissue callus or subsequent fracture callus remodeling, μCT of each fracture callus at 42 DPF was performed in WT and Fbg–/– mice. Consistent with radiographic data, 3D and 2D μCT reconstructions (Figure 3) demonstrated cortical bridging at fracture sites in both genotypes. Quantitative assessments of each fracture callus by μCT (Table 2) disclosed no significant differences in geometric properties (polar moment of inertia [pMOI]), structural properties (anisotropy), or tissue mineral density (TMD) of fracture calluses when comparing genotypes. Histological sections verified the complete transition of soft-tissue callus composed of a chondroid matrix into hard-tissue callus containing woven bone and also documented cortical bridging over the fracture site (Figure 3 and Table 1). Together, these data demonstrate that fibrin is not required for the formation of the hard-tissue callus union or the subsequent fracture callus remodeling.

Figure 3. Fibrin is not essential for hard-tissue callus union.

Top panels show 3D μCT reconstructions of femurs from WT and Fbg–/– mice at 42 DPF. Note there are no clear structural differences in animals of each genotype (white boxes denote site of fracture; yellow pound symbols denote areas of cortical bridging). Middle panels show coronal and sagittal 2D μCT images, further demonstrating cortical bridging by hard-tissue callus in both WT and Fbg–/– mice (yellow pound symbols). Bottom panels show safranin O and MSB staining establishing cortical bone union in both WT and Fbg–/– mice (yellow pound symbols). n ≥ 10 for each genotype. Scale bars: 1 mm.

Table 2. Bone properties of fractured femur at 42 DPF were analyzed using Scanco Medical μCT software.

Plasmin is required for fracture repair.

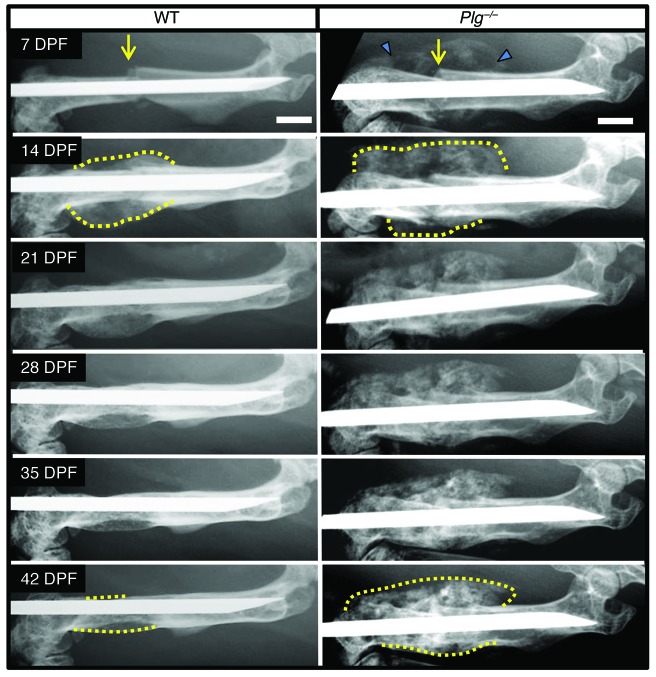

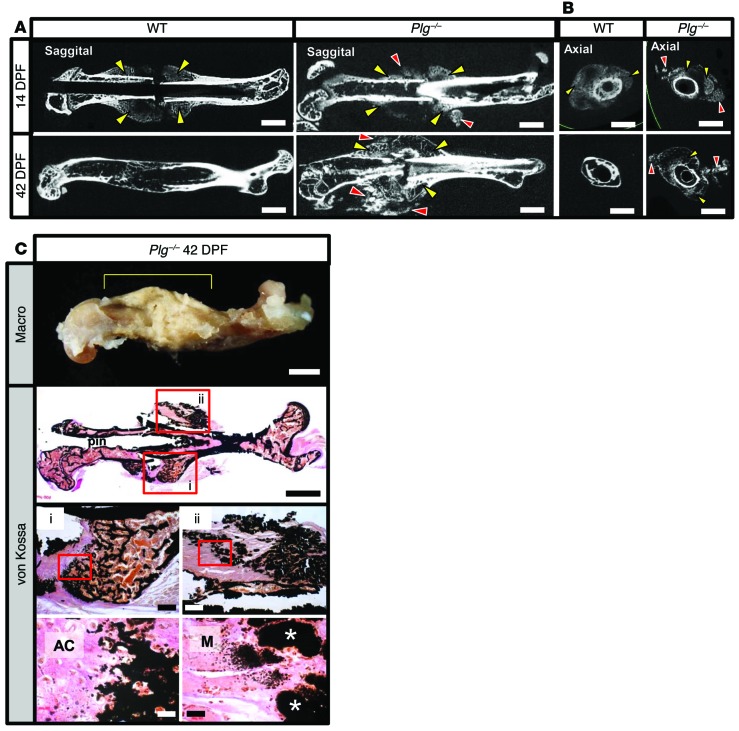

Since fibrin was dispensable for fracture repair, we next sought to explore the hypothesis that the timely removal of a fibrin matrix is important during fracture repair. As a first direct test of this concept, we used gene-targeted mice devoid of circulating plasminogen (Plg–/–), the plasmin zymogen that supports efficient degradation of the fibrin matrices. In Plg–/– mice, but not in WT mice, we observed extensive mineralization surrounding the fracture site at 7 DPF (Figure 4). At 14 DPF, the area of mineralization in Plg–/– mice was much larger than in WT mice. Union of the proximal and distal hard-tissue calluses was difficult to determine radiographically because of the presence of diffuse mineralization around the fracture site. WT mice achieved hard-tissue callus union at 21 DPF that was subsequently remodeled between 21 and 42 DPF. In contrast, Plg–/– mice at 42 DPF displayed no apparent radiographic evidence of hard-tissue callus remodeling and exhibited persistent diffuse mineralization surrounding the fracture site. The early aberrant mineralization surrounding the fracture site noted in Plg–/– mice was suggestive of heterotopic ossification (Figure 4). Further analysis of the hard-tissue callus formation at the site of fracture in Plg–/– mice showed foci of mineralization within soft tissues distant from the fracture site in sagittal and axial μCT images acquired at 14 DPF and 42 DPF (Figure 5, A and B). von Kossa staining of tissue sections demonstrated that the soft tissue mineralization seen on μCT represents calcium deposition within skeletal muscle fibers (Figure 5C). These findings are characteristic of heterotopic ossification and suggest impaired plasmin activity as a mechanism for this pathological response to tissue injury. Therefore, loss of plasmin was associated with impaired hard-tissue callus formation and heterotopic ossification.

Figure 4. Plasminogen-deficient mice show abnormal hard-tissue callus formation.

Serial radiographic analysis of fractured femurs (yellow arrows) revealing marked differences in the formation (blue arrowheads) and macroscopic remodeling of the hard-tissue fracture callus (dashed yellow lines) in WT and Plg–/– mice. Note that relative to WT mice, the fracture callus in Plg–/– mice was hypertrophic and failed to undergo remodeling of the macroscopic hard-tissue callus over the first 6 weeks after fracture. In addition, both appreciable and persistent soft-tissue mineralization were noted adjacent to the injury site (blue triangles). Representative images of n = 15 for each genotype; see Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 4 for quantification. Scale bars: 1 mm.

Figure 5. Heterotopic ossification in plasminogen-deficient mice.

(A) 2D μCT sagittal slices of WT and Plg–/– mice at 14 and 42 DPF. 14 DPF images show hard-tissue callus formation in both WT and Plg–/– mice (yellow arrowheads). In addition, separate foci of mineralization in soft tissue away from the fracture callus seen only in Plg–/– mice are suggestive of heterotopic ossification (red arrowheads). By 42 DPF, the hard-tissue fracture callus has largely remodeled in WT mice. In contrast, the fracture callus in Plg–/– mice is not only persistent, but also hypertrophic and disorganized, with an irregular pattern of mineralization. Scale bars: 1 mm. n ≥ 13 for each genotype. (B) 2D μCT axial images of fractured femurs at 14 and 42 DPF in Plg–/– mice show that the areas of soft-tissue mineralization (red arrowheads) are distinct from the femoral fracture callus (yellow arrowheads), consistent with heterotopic ossification. Scale bars: 1 mm. n ≥ 13 for each genotype. (C) Macroscopic photograph of lateral aspect of a fractured femur of a Plg–/– mouse at 42 DPF (macro, yellow bracket denotes fracture callus). Nondemineralized tissue sections from the fracture callus of Plg–/– mice were stained with von Kossa and van Gieson solution to identify regions of hard-tissue callus formation (box i) and heterotopic ossification (box ii). Red boxes denote regions shown at higher power magnification. Foci of heterotopic ossification are denoted by white asterisks. Scale bars: 1 mm (top and second row); 200 μm (third row); 20 μm (bottom row). AC, avascular cartilage; M, muscle.

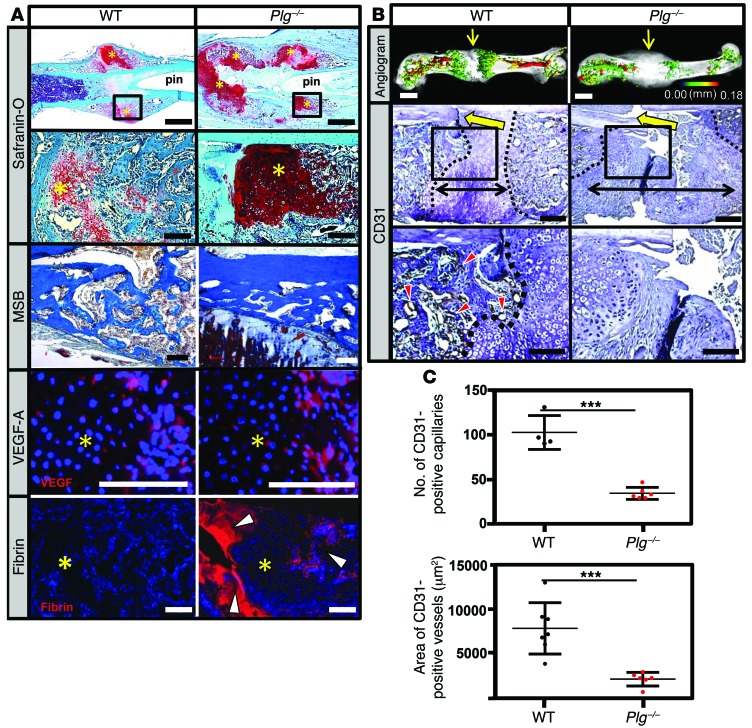

In order to better understand the role of plasmin during fracture repair, we next examined in detail both callus formation and vascularization. Histologic examination of fracture callus at 14 DPF in Plg–/– mice revealed a large noncentrally located soft-tissue callus composed of an avascular chondroid matrix with reactive woven bone at the periphery of the fracture callus (Figure 6A). At this time, VEGF expression was observed in the hypertrophic chondrocytes contained within the chondroid matrix from both WT and Plg–/– mice, consistent with endochondral-mediated angiogenesis (Figure 6A). Abundant fibrin within the fracture callus of Plg–/– mice was interposed between the separated femoral cortices and within the newly formed hard-tissue callus at the periphery of the fracture callus (Figure 6A). In contrast, WT mice exhibited no detectable fibrin at the fracture site at 14 DPF. Since endochondral hard-tissue callus formation requires vascular invasion of soft-tissue callus, we next determined whether fibrin clearance is essential for vascularization of the fracture callus. Angiograms of the fracture callus in WT mice demonstrated robust revascularization within the hard-tissue callus proximal and distal to the fracture site (Figure 6B). In contrast, Plg–/– mice showed a pronounced lack of vascularization characterized by the absence of identifiable blood vessels, as illustrated by reduced CD31 staining in the central region of the fracture site (Figure 6B) and significant reductions in both the number and total area of blood vessels in the fracture callus (Figure 6C). These data suggest that plasmin is required for proper endochondral-mediated vascularization of the fracture callus as well as the timely conversion of the soft-tissue callus to newly formed woven bone.

Figure 6. Plasmin is not required for soft-tissue callus formation, but is essential for vascularization of fracture callus.

(A) Safranin O– and MSB-stained sections and immunofluorescence for VEGF-A and fibrin in the fracture callus at 14 DPF. Safranin O staining reveals the presence of the soft-tissue callus, while MSB-stained sections demonstrate that, while reduced in quantity compared with WT mice, the newly formed bone is histologically indistinguishable from newly formed bone in WT mice. VEGF immunofluorescence staining reveals VEGF expression within the hypertrophic chondrocytes (avascular soft-tissue callus, yellow asterisks) of WT and Plg–/– mice. Fibrin immunofluorescence reveals excessive fibrin deposition (white arrowheads) at the fracture site and in the hard-tissue callus of Plg–/– mice at 14 DPF compared with WT mice. Scale bars: 1 mm (top row); 100 μm (second, third, and fourth rows). (B) Representative 3D μCT reconstructions of angiogram contrast–perfused femurs show reduced revascularization of the fracture callus in Plg–/– mice at 14 DPF (color scale bar indicates vessel size range: black = 0.00 mm, red = 0.18 mm). Immunohistochemistry for CD31-positive vessels (red arrowheads) in the fracture site (yellow arrows). The interface of avascular soft-tissue callus and vascularized hard-tissue callus is marked by a black dashed line. The fracture gap is defined as the region between hard-tissue calluses (black double arrows). Scale bars: 1 mm (top row); 100 μm (middle and bottom rows). (C) Statistical analysis (Student’s t test) comparing number (top) and total area (bottom) of CD31-positive blood vessels in the callus. Four sections in each sample were averaged to constitute a single replicate (1 n). ***P < 0.01. Error bars represent SD. n ≥ 4 for each genotype.

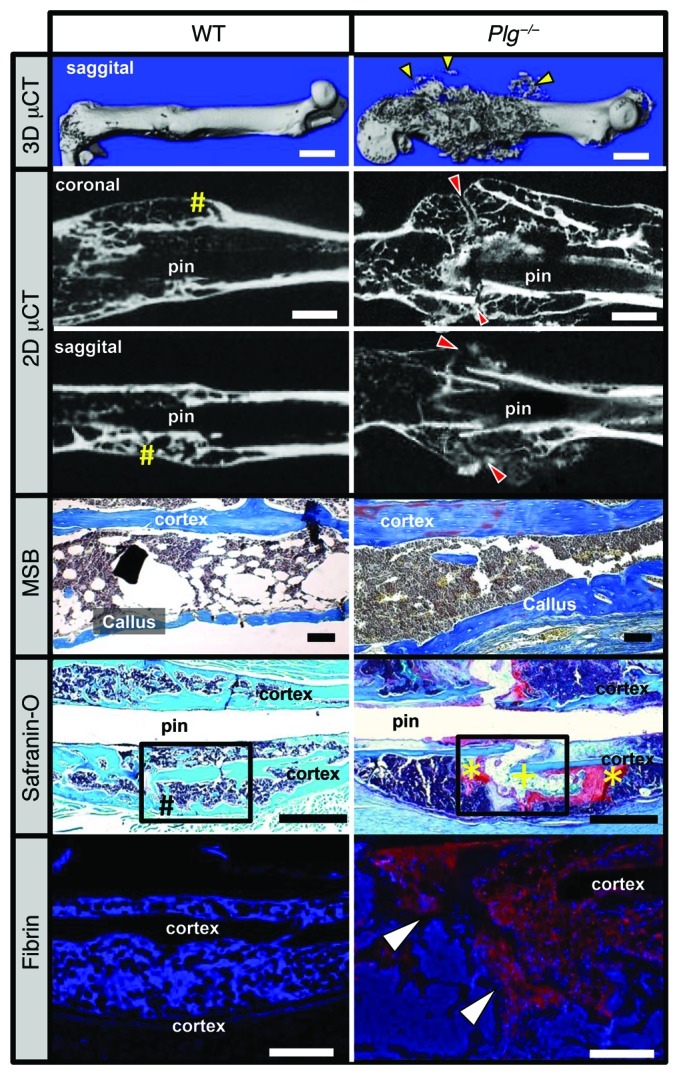

To determine whether a plasminogen deficiency affects cortical bridging of the fracture callus and to elucidate the structure and remodeling of hard-tissue callus in the absence of plasmin, μCT was performed on WT and Plg–/– mice at 42 DPF. Consistent with radiologic data, representative images of 3D μCT reconstructions of a fractured femur from Plg–/– mice showed a markedly disorganized fracture callus (Figure 7). In addition, while 2D μCT reconstructions of fracture sites in WT mice showed evidence of cortical bridging over the fracture site, the hard-tissue callus in Plg–/– mice failed to unite across the fracture site (Figure 7 and Table 1). This failure to unite was associated with an absence of remodeling of the hard-tissue callus back to the original femoral cortical contour in Plg–/– mice. Quantitative evaluations of fracture callus by μCT at 42 DPF demonstrated that Plg–/– mice show alterations in composition and structure including elevated pMOI, bone volume, and bone area (Table 2). Together, these data independently validate radiograph evidence suggesting impaired callus formation and remodeling in Plg–/– mice. Histological examination of the newly formed bone in the fracture callus by martius scarlet blue (MSB) staining revealed no morphologic differences in bone formation between WT and Plg–/– mice. Furthermore, examination of the fracture gap in Plg–/– mice by safranin O staining confirmed absence of cortical bridging and persistent soft-tissue callus surrounding a central area of fibrosis at the fracture site. These data demonstrate that, although bone formation is histomorphologically normal, there is a delay in replacing the avascular soft-tissue callus with vascularized hard-tissue callus in Plg–/– mice (Figure 7). Immunohistochemistry revealed that fibrin was centrally located over the fracture site and within the area of fibrosis opposing the ends of the fracture callus (Figure 7). Together, these data confirm that plasmin is essential for the removal of fibrin from the fracture callus and endochondral-mediated vascularization of the fracture callus as well as the appropriate formation and union of new bone at the fracture site.

Figure 7. Plasmin is required for hard-tissue callus union.

3D μCT reconstruction of a displaced fracture at 42 DPF shows evidence of soft-tissue mineralization away from the fracture callus in Plg–/– mice (yellow arrowheads). Coronal and sagittal 2D μCT slices of WT and Plg–/– mouse femurs show cortical bridging by hard fracture callus (yellow pound symbols) in WT mice. In contrast, a failure to unite the proximal and distal hard-tissue callus was observed in Plg–/– mice (red arrowheads). MSB stains demonstrate the presence of organized woven bone formation within the callus, and safranin O–stained sections confirm complete cortical bridging in WT mice (black pound symbol), whereas the fracture gap in Plg–/– mice remains composed of chondroid soft-tissue callus (yellow asterisks) and fibrous tissue (yellow plus sign) without evidence of cortical bridging. Immunofluorescence microscopy for fibrin shows abundant fibrin deposition at the fracture site in Plg–/– mice (red stain with DAPI blue counterstain, white arrowheads). Black boxes in safranin O sections indicate region displayed for fibrin immunofluorescence. n = 15 for each genotype. White scale bars: 1 mm (top two rows), 500 μm (bottom row); black scale bars: 1 mm.

Knock down of the fibrin precursor, fibrinogen, restores fracture repair and limits heterotopic ossification in plasminogen-deficient mice.

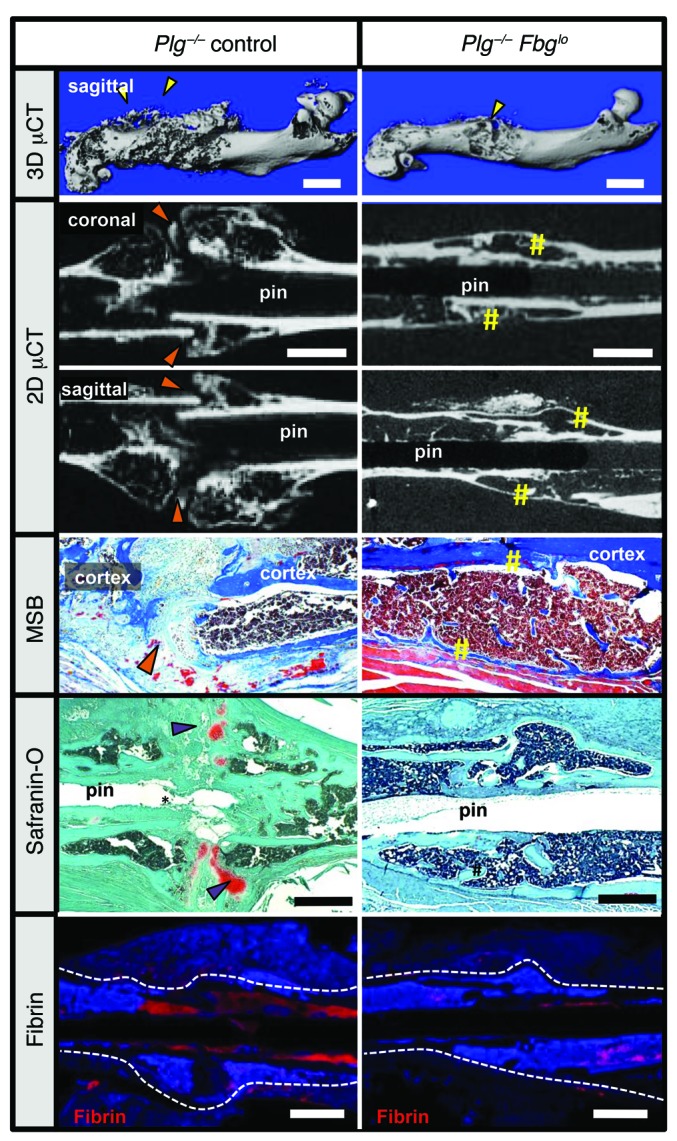

Since both plasminogen and plasmin have biologic functions other than fibrin removal, we next determined whether a failure to remove fibrin was responsible for impaired fracture repair and heterotopic ossification. Here, circulating fibrinogen levels were reduced in Plg–/– mice using an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), gapmer, designed to selectively impede hepatic fibrinogen protein production (Supplemental Figure 3). Studies using these Plg–/– Fbglo cohorts were controlled with Plg–/– mice treated with a nonsense ASO of similar structure, resulting in Plg–/– control cohorts. Following fracture, μCT was performed to define the structure of the hard-tissue callus and determine fracture callus union in Plg–/– Fbglo mice at 42 DPF. 3D μCT reconstructions demonstrated a more organized hard-tissue callus (Figure 8, 3D μCT) in Plg–/– Fbglo mice compared with Plg–/– control mice. As an extension of this work, 2D μCT reconstructions were done to better define cortical bridging of the fracture site by the hard-tissue callus. In contrast to Plg–/– control mice, which fail to form a complete hard-tissue callus bridge over the fracture gap by 42 DPF (Figure 8, 2D μCT), the gap in most Plg–/– Fbglo mice (10 of 13 mice, Table 1) was found to be overlaid with a well-formed hard-tissue callus (Figure 8, 2D μCT). Histological sections and histomorphometric analysis also demonstrated more organized and mature-appearing fracture calluses (as evidenced by the presence of reactive woven bone in the fracture callus, a lack of residual soft-tissue callus, and robust cortical bridging) in Plg–/– Fbglo mice relative to Plg–/– control mice (Figure 8 and Table 1). Quantitative μCT evaluation confirmed that the fracture calluses of Plg–/– Fbglo mice had significantly improved geometric and structural properties compared with those of Plg–/– control mice (Table 2). In contrast to Plg–/– control mice, Plg–/– Fbglo mice showed significant increases in TMD and decreases in bone volume, bone area, and pMOI, all indicative of a well-formed, remodeled callus (Table 2). To confirm that the ASO-mediated fibrinogen knockdown was successful in preventing fibrin deposition within the fracture callus, we histologically investigated for the presence of fibrin at the fracture site (Figure 8). Immunostaining confirmed a marked reduction in fibrin deposition in the fracture callus and within the intramedullary space of Plg–/– Fbglo mice as compared with Plg–/– control mice.

Figure 8. Fibrinogen knockdown rescues hard-tissue callus union.

Representative 3D and 2D μCT images, safranin O–stained sections, and immunofluorescence microscopy for fibrin in Plg–/– and Plg–/– Fbglo mice. 3D μCT images demonstrate heterotopic ossification (yellow arrowheads) and poorly macroscopically remodeled hard-tissue fracture callus in Plg–/– mice for 42 DPF formation. 2D μCT of the fracture sites in Plg–/– Fbglo mice shows cortical bridging by hard-tissue callus (yellow sharps), whereas this is not shown in Plg–/– mice (orange arrowheads). Histological sections confirmed united fractures with the presence of reactive woven bone in Plg–/– Fbglo mice in contrast to the disorganized callus with residual soft-tissue callus in Plg–/– mice (purple arrowheads). Immunofluorescence for fibrin confirms markedly less fibrin in the fracture site in Plg–/– Fbglo mice (red stain, fibrin, with DAPI blue counterstain). White dotted line denotes border of the femur and fracture callus. Scale bars: 1 mm. n ≥ 5 for each genotype.

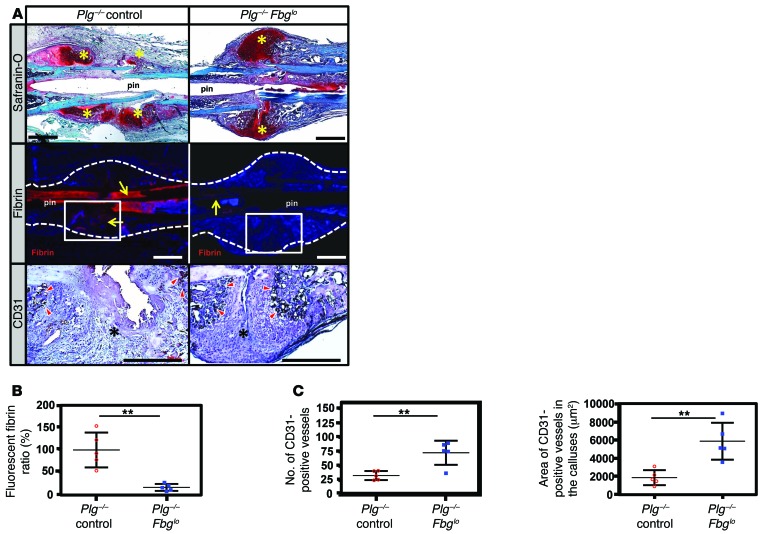

As pharmacological fibrinogen suppression rescued cortical bridging at 42 DPF, we next examined the fracture callus at an earlier time (14 DPF), when both the soft-tissue and hard-tissue callus were present for better assessment of fracture repair. Histologic evaluation of fracture callus in Plg–/– Fbglo mice at 14 DPF revealed a well-formed and organized soft-tissue callus flanked by hard-tissue callus that was similar to that seen in WT mice (Figure 9A). In contrast, the soft-tissue callus in Plg–/– mice was poorly formed and disorganized. Immunofluorescence staining for fibrin at 14 DPF confirmed persistent fibrin at the fracture site in Plg–/– mice, but a marked reduction of fibrin was observed in Plg–/– Fbglo mice (Figure 9, A and B). Fracture sites were examined for CD31 immunostaining to determine whether fibrinogen knockdown resulted in increased vascularity of the fracture callus. Increased numbers of CD31-positive cells and the percentage of total tissue area defined by CD31-positive vessels at the periphery of the fracture callus were noted (Figure 9, A and C). These data demonstrate that impaired fibrinolysis results in persistent fibrin, which compromises soft-tissue callus formation and the normal vascularization of the fracture callus in Plg–/– mice.

Figure 9. Fibrinogen knockdown rescues impaired callus formation and revascularization.

(A) Representative histological sections of femoral fracture sites from Plg–/– mice treated with ASO as a control and Plg–/– mice (Plg–/– control; n = 5) treated with an ASO against fibrinogen (Plg–/– Fbglo; n = 10) at 14 DPF. Sections were stained with safranin O and assessed by immunofluorescence for fibrin and by immunohistochemistry for CD31. Whereas the fracture callus of Plg–/– mice is somewhat disorganized, with multiple foci of chondroid soft-tissue callus (safranin O, yellow asterisks), the callus in Plg–/– Fbglo mice is more organized, with a central soft-tissue callus bordered proximally and distally by hard-tissue callus. There is markedly reduced fibrin deposition in the fracture callus of Plg–/– Fbglo mice compared with Plg–/– control mice (yellow arrows; white box denotes area shown for CD31 staining). CD31 highlights numerous CD31-positive cells lining blood vessels in the hard-tissue callus of Plg–/– Fbglo mice (red arrowheads), with fewer vessels in Plg–/– mice (black asterisks denote areas of soft-tissue callus in fracture gap). Scale bars: 1 mm. Statistical comparison (Student’s t test) of (B) fibrin deposition at fracture site, (C) number of CD31-positive vessels in the callus (left), and total area of CD31-positive vessels (right). n ≥ 5 for each group. Four sections in each sample were averaged to constitute a single replicate (1 n). **P < 0.01. Error bars represent SEM.

Fibrin deposits at the interface between the avascular soft-tissue callus and the vascularized hard-tissue callus.

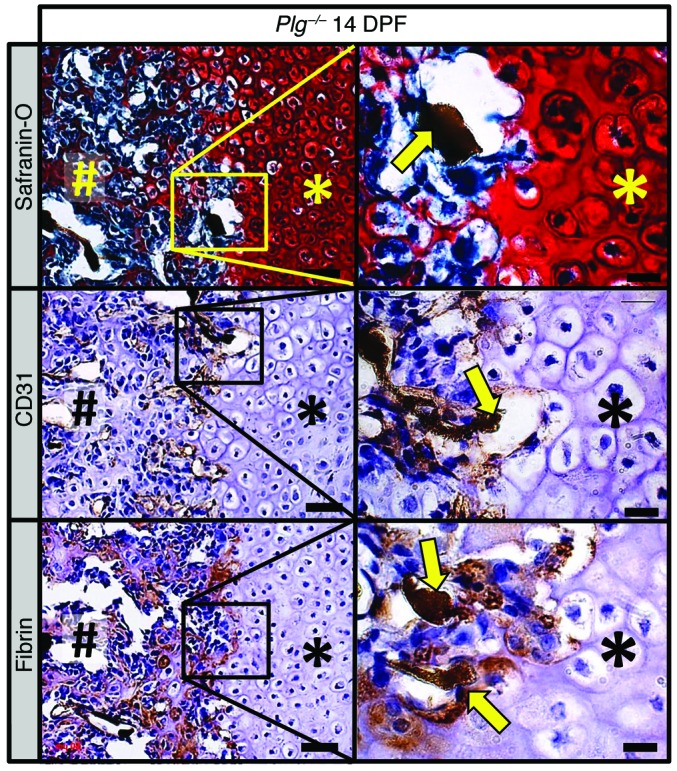

Since Plg–/– mice had a persistent fibrin matrix associated with both impaired bone formation and vascularization, we next determined whether fibrin is present at the interface of the avascular soft-tissue callus and vascularized hard-tissue callus (Figure 10), where it might serve as a barrier to cell migration. We observed angiogram contrast material at the interface between soft- and hard-tissue callus indicative of chondrocyte-mediated recruitment of vascularity, which supports transport of mesenchymal progenitors and newly forming bone into the soft-tissue callus. Consistent with previous findings (1, 27), CD31 immunostaining revealed endothelial cells surrounding patent vessels located at the leading edge of the hard-tissue callus (Figure 10). Immunohistochemistry for fibrin performed on serial sections show fibrin deposits interposed between the soft- and hard-tissue callus and surrounding patent vessels. Fibrin localized near the sites of active vascularization, suggesting that persistent fibrin deposition at these sites may impede the remodeling of the soft-tissue callus into a vascularized hard-tissue callus (Figure 10). Overall, these data support the concept that persistent fibrin may act as a physical barrier to revascularization during endochrondral ossification, thereby inhibiting the replacement of soft-tissue callus with hard-tissue callus.

Figure 10. Fibrin is deposited at the interface between avascular soft-tissue callus and vascularized hard-tissue callus.

Histological evaluation of the fracture callus of Plg–/– mice at 14 DPF discloses angiogram contrast–perfused blood vessels (safranin O, yellow arrow) at the interface of the soft-tissue callus (asterisks) and hard-tissue callus (pound symbols). Immunohistochemical staining for CD31 (brown staining) highlights thin-walled blood vessels filled with angiogram contrast material (CD31, yellow arrows) at the interface of soft- and hard-tissue callus. Immunohistochemistry also identifies fibrin (brown staining) at this interface surrounding angiogram contrast–perfused blood vessels (fibrin, yellow arrows). Immunohistochemistry slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bars: 50 μm (left column); 20 μm (right column). Representative of n = 5.

Discussion

These studies reveal the unanticipated finding that local deposition of the coagulation provisional matrix protein, fibrin, is not essential for fracture repair. The findings fundamentally revise the long-standing and prevailing view that, during fracture repair, fibrin matrices serve as the initial scaffolds for healing damaged bone and are instrumental for local inflammatory processes, neovascularization, and mesenchymal progenitor cell migration into damaged bone. While the presence of multiple integrin- and nonintegrin-binding motifs capable of promoting cellular migration on fibrin strongly favors the notion that fibrin is critical to fracture repair (28), our data refute the current paradigm. The present studies clearly demonstrate that fibrin is not essential for fracture repair in mice, since we did not observe any detectable change in the outcome of fracture repair in the absence of fibrin. Of course, consistent with the contribution of fibrin to hemostasis, the availability of fibrin(ogen) did limit local hemorrhage within the injured zone following long-bone fracture. Nonetheless, fibrin matrices do not appear to be strictly required for the mesenchymal cell recruitment, activation, and differentiation events or other physiological processes essential for efficient bone repair. Perhaps even more provocatively, the present studies show that instead, timely and efficient removal of fibrin is essential for fracture repair. Plasmin-mediated clearance of fibrin is vital for the vascularization of the soft-tissue callus and subsequent formation and remodeling of the hard-tissue callus. Our results direct a reevaluation of the role of fibrin in fracture repair.

Persistent fibrin deposition at the fracture site impedes fracture healing and is counterproductive to bone repair through multiple potential mechanisms. Given that angiogenesis is requisite for osteoblast-mediated matrix mineralization during fracture repair (27, 29–33) and that vascular dysfunction and hypofibrinolysis are common to many comorbid conditions associated with delayed fracture repair (17–20, 23, 34–38), we postulated that impaired fracture repair in Plg–/– mice is the result of impaired angiogenesis. Just as in the growth plate, endochondral angiogenesis in fracture repair is regulated by hypertrophic chondrocytes that release VEGF-A, calcium, and phosphate, which direct endothelial and osteoprogenitor cells to form new blood vessels and bone. Hypofibrinolysis in the absence of plasmin(ogen) did not affect development of chondroid soft-tissue callus or expression of VEGF‑A in hypertrophic chondrocytes, but instead resulted in persistent fibrin deposition at the interface between hypertrophic chondrocytes in soft-tissue callus and invading endothelial and osteoblastic cells in the leading edge of the hard-tissue callus. The specific location of fibrin deposition and the paucity of extramedullary vasculature that typically develops from the shunting of blood flow from the intramedullary vasculature after fracture (1) support the notion that persistent fibrin deposition represents a physical barrier that prevents cellular trafficking and tissue reorganization. Indeed, such a mechanism is strongly supported by our finding that reducing fibrinogen prior to fracture in plasminogen-deficient mice partially rescues endochondral angiogenesis and fracture union. Thus, these studies highlight the strict requirement for plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis for the recruitment of endothelial and osteoblast precursors by hypertrophic chondrocytes, thereby inhibiting endochondral angiogenesis and ossification.

Importantly, reducing plasma fibrinogen levels, and secondarily fibrin deposition, substantially rescues defective fracture repair in plasminogen-deficient animals. Effective depletion of fibrinogen by ASO treatment was confirmed by the absence of detectable fibrinogen levels in plasma and significant (P = 0.0015) reduction in fibrin deposition within fracture callus. Although fibrinogen ASOs are a convenient and effective method of reducing fibrinogen expression in controlled experimental settings, several factors should be considered before contemplating their clinical utility. Because the half-life of circulating fibrinogen is relatively long (39) (~5 days) and fibrin is deposited immediately after injury, ASO-based interventions would likely be more applicable for elective surgeries than for trauma. However, because fibrin deposition may be relatively dynamic, intervention with ASOs may also have therapeutic utility in trauma settings. Alternate clinical applications of our findings might include enhancing fibrinolytic activity to improve the incidence of successful fracture repair. Future investigations are required to determine the clinical efficacy of fibrinogen ASOs or alternative methods designed to promote fibrinolysis on bone regeneration after either trauma or elective orthopedic surgical procedures.

The incomplete rescue of fracture repair following ASO-mediated fibrinogen depletion may be due to residual fibrin or function of plasminogen independent of fibrinolysis activity. While the principal role of plasmin in fracture repair appears to be fibrin clearance in support of efficient fracture callus neovascularization and bone formation, our studies do not formally exclude that plasmin also supports the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages (40) that phagocytose necrotic debris from the site of injury and inhibit the acute inflammatory response (41). Thus, plasmin deficiency may subtly prolong the necroinflammatory phase of fracture repair independently of fibrin degradation. Plasmin activity also has been proposed to support the release of growth factors important for wound repair, such as TGF-β (42, 43) and VEGF (44). Finally, plasmin may have direct effects on the osteoblast within the fracture callus. Inhibition of plasmin delays mineralization and differentiation of in vitro osteoblast cultures grown in the absence of fibrin (45), suggesting that plasmin may directly promote maturation of osteoblast precursors to mature osteoblasts during fracture repair. Interestingly, Kawao et al. proposed that bone repair is largely independent of plasminogen-mediated fibrinolytic activity (46). The seeming contradiction with the present findings could be due to differences in the bone-injury model employed (a drill hole bone defect) or differences in the methods and/or effectiveness of reducing circulating fibrinogen levels. While future studies are required to further explore nonfibrinolytic roles of plasmin during fracture repair, our data indicate that plasmin activity is, at least in part, essential for fracture repair, acting by supporting fibrin clearance.

Following development of hard-tissue callus, remodeling the callus to the original macroscopic architecture of the prefracture bone was also substantially delayed in the absence of plasminogen. The remodeling of newly formed bone in fracture callus becomes clinically apparent after osseous union across the fracture site (1). Thus, it is plausible that loss of plasminogen activity affects osteoclastogenesis, osteoclast function, and/or osteoclast/osteoblast interactions. In support of this, plasminogen and its principle activators (urokinase-type plasminogen activator [uPA]/tissue-type plasminogen activator [tPA]) have been reported to activate multiple elements of bone remodeling (47, 48). However, depletion of fibrinogen partially rescued fracture union and remodeling in the setting of a complete deficiency of plasminogen, indicating that, although plasmin and its activators are capable of driving the bone remodeling process, plasminogen is not essential for bone remodeling associated with fracture repair. Instead, these data potentially implicate fibrin as a negative regulator of bone remodeling. However, preliminary analyses suggest that similar numbers of osteoclasts surrounded newly formed woven bone spicules following fracture in all genotypes analyzed (not shown). Additionally, in studies previously reported, local fibrin deposition within bone tissue was found to directly stimulate osteoclastogenesis through engagement of CD11b/CD18 on monocytes, thereby inducing severe osteoporosis (12). Thus, it is postulated that the persistent presence of fibrin, if anything, likely drives increased osteoclastogenesis during fracture repair. As an alternative, the most straightforward explanation of delayed callus remodeling in the absence of plasminogen is the delay in vascular and cortical union. Considering that the greater majority of plasminogen-deficient mice did not achieve union by the termination of the studies, a longer study period will be required to test this hypothesis.

Development of heterotopic ossification in skeletal muscle adjacent to the fracture was both a striking and unexpected finding. Heterotopic ossification often occurs following musculoskeletal trauma associated with electrocution, burn/blast injuries, or with neurological injury (49–52). Although these conditions have been anecdotally associated with diminished fibrinolytic activity (53–55), there are no reports that suggest that plasmin(ogen) is directly involved in preventing heterotopic ossification. It has been determined that absence of uPA results in spontaneous heterotopic ossification in mice with Duschenne’s muscular dystrophy, although it was not determined whether this was secondary to a deficiency of downstream plasmin activity (56). Moreover, fibrin can bind calcium phosphate and promote mineralization (and in fact has been used in bone graft substitutes for this property) (57). Heterotopic ossification was significantly reduced when fibrinogen levels were reduced in plasminogen-deficient mice (P < 0.05; see Table 1). Therefore, we posit that fibrin and plasmin are potential determinants of traumatic heterotopic ossification. Future studies are required to better define the precise mechanism by which plasminogen and fibrinogen contribute to heterotopic ossification following fracture.

Our results suggest a new paradigm for the roles of fibrin and plasmin during fracture repair. Fibrin is not essential for fracture repair, and indeed, fibrin must be timely and effectively removed to allow fracture vascularization and repair. Given that impaired fibrinolysis and vascular dysfunction are both seen in comorbidities associated with poor fracture repair (17–20, 23, 34–38) and that impaired angiogenesis is hypothesized to be a primary cause of delayed union or nonunion, our findings suggest that persistent or excessive fibrin deposition at the fracture site is the molecular mechanism of impaired fracture angiogenesis and subsequent delayed or nonunion in these conditions.

Methods

Animals

Homozygous breeding pairs of Plg–/– and Fbg–/– mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background were previously described (58, 59); these were bred in the animal facility of Vanderbilt University with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. At the time of study, both fibrinogen- and plasminogen-deficient mice were 11 generations from the founding pair of mice. The C57BL/6 mouse WT strain, recommended by Jackson Laboratory as the control strain for comparison with Plg–/– and Fbg–/– mice, was obtained from Jackson Laboratory. To avoid sex-related confounding effects on developmental bone growth and fracture repair, only male mice were used in this study. All mice were used for fracture study at 8 weeks of age.

Murine femur fracture model

Mice were placed under anesthesia using 60 mg/kg ketamine and 4 mg/kg xylazine. The fur overlying the medial of the thigh was shaved and the skin prepped with betadine prior to making an incision. A 10- to 12-mm long medial incision of mid to distal femur was made, and mid-shaft femur was exposed by blunt dissection of muscle. After patella was moved laterally, fracture was created by cutting the midshaft of the femur with fine scissors. A 23-gauge needle (0.6414 mm) was inserted into the intercondylar notch using a trephine technique and advanced through the intramedullary canal to the sub- or intertrochanteric femur. Before closure, we confirmed that the fracture was neither partial nor comminuted. The incision was closed by silk suture. Fracture repair was followed radiographically using a Faxitron x-ray system (4 seconds at 35 kV) weekly. Mice were sacrificed at 14 and 42 days after surgery and samples processed for μCT, MICROFIL (MV-122 Flow Tech Inc.), and histology.

Imaging

Gross pictures.

The fractured femora were dissected after we sacrificed the mice. We removed the surrounding muscle around the femora. We carefully removed muscle using microforceps so as not to damage any mineralized tissues around the fracture site. After fixing the specimens in 4% paraformaldehyde, we took photographs with an Olympus dissecting microscope.

X-ray.

X-ray was performed as previously described (60). Briefly, mice were placed in the prone position and imaged for 4 seconds at 45 kV using a Faxitron LX 60. Mice were sacrificed at various time points (7–42 days) following fracture.

Angiography.

Perfusion with MICROFIL vascular contrast was conducted as previously described (61–64). Briefly, mice were euthanized and positioned supine; a thoracotomy extending into a laparotomy was performed. The left ventricle of the heart was cannulated using a 25-gauge butterfly needle. The inferior vena cava (IVC) was transected proximal to the liver and the entire vasculature subsequently perfused with 9 ml of warm heparinized saline (100 units/ml in 0.9% saline) through the left ventricle cannula to prevent erythrocyte aggregation and thrombosis. A perfusion pump (Braintree Scientific Inc.) was used to achieve consistent perfusion at the ratio of 2 ml/min. Exsanguination and anticoagulation were deemed complete upon widespread hepatic blanching with clear fluid extravasating from the IVC. Mice were then perfused with 9 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin at 2 ml/min followed by 3 ml of MICROFIL vascular contrast polymer at 0.5 ml/min. To best verify complete filling of the vasculature, gross images of the liver, the last organ to be perfused prior to extravasation through the IVC, were examined for extravascular pooling. Mice were excluded from the study if complete hepatic blanching prior to MICROFIL was not achieved, if contrast was not clearly or uniformly visible in the hepatic vasculature, or if extravascular pooling occurred. Due to the similarities in the density of bone and MICROFIL contrast, all fracture samples that were already taken by s-ray were then decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8, prior to x-ray and μCT imaging.

μCT.

μCT images were acquired (μCT40, Scanco Medical) following specimen harvest of the fractured femurs at 55-kVp, 145-uA, 20-0ms integration, 500 projections per 180o rotation, with a 20-μm isotropic voxel size. After reconstruction, a volume of interest was selected comprising the medullary space starting at the center of fracture site and extending 0.5 mm additionally both distally and proximally. The bone tissue within the VOI was segmented from soft tissue using a threshold of 220 per thousand (or 450.7 mgHA/cm3), a Gaussian noise filter of 0.2, and support of 1. Bone volume and bone area were calculated using Scanco Medical evaluation software. A combination of μCT parameters was chosen to describe the material and geometrical properties of the callus. TMD was used for description of fracture repair. TMD is the average of attenuation value of all voxels above the threshold and within the total volume. This value has the units of mgHA/cm3 because a hydroxyapatite phantom is scanned weekly, providing the conversion of attenuation to equivalent density of HA. pMOI and anisotropy describe the geometrical distribution of this material and are associated with torsional distribution strength. These parameters were determined by including all mineralized tissue within the outer perimeter of the fracture callus from μCT images by the Scanco Medical script for midshaft evaluation.

Histological analysis

Specimens removed for histology were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) for approximately 5 days. Subsequently, they were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, cleared, and embedded in paraffin. Each sample was sectioned sagittally at 6 μm and used for staining.

Safranin orange/fast green stains (safranin O)

Paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned onto slides and deparaffinized and rehydrated as for H&E above. Slides were placed in freshly filtered working Weigert’s hematoxylin for 10 minutes and immediately washed in running tap water for 10 minutes. Slides were then placed in working 0.1% fast green solution for 5 minutes and rinsed quickly in 1% acetic acid for no more than 10 to 15 seconds. Slides were then placed in 0.1% safranin O solution for 5 minutes. Finally, slides were dehydrated through 2 changes of 95% EtOH and 100% EtOH for 3 minutes each and cleared in 2 changes of xylene for 5 minutes. Slides were then coverslipped with Permount.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin was removed from the slides using 2 xylene washes for 10 minutes each. The slides were then rehydrated in the following series of solutions: 100% EtOH twice for 2 minutes each, 90% EtOH for 2 minutes, 80% EtOH for 2 minutes, 70% EtOH for 2 minutes, dH2O for 2 minutes. Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.1 M citric acid and 0.1 M sodium citrate. Slides were heated for about 2 minutes in the microwave. Subsequently, the endogenous peroxide was quenched with the 3% H2O2 for 15 minutes. After washing the slide gently with PBS 3 times, the sections were then blocked for 30 minutes using blocking solution (TSA kit; PerkinElmer) to minimize nonspecific staining. The slides were immunostained for rabbit anti-mouse fibrin using a 1:1000 dilution of the primary antibody (fibrin) in the blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C. Slides incubated without primary antibody served as negative controls. The slides were washed 3 times in TNT wash buffer for 5 minutes each. We applied biotin goat anti-rabbit Ig antibody (BD Biosciences — Pharmingen, 550338) for secondary antibody. After TSA amplification, the Dako EnVision+ HRP/DAB System (catalog K4007, Dako) was used to produce localized, visible staining. All slides were incubated for equal amounts of time. They were then rinsed in dH20 for 2 minutes, counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, and coverslipped. Slides were immunostained for rat anti-mouse CD31 using a 1:50 dilution of the primary antibody (CD31) in the blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C. Slides incubated without primary antibody served as negative controls. Slides were washed 3 times in TNT wash buffer for 5 minutes each. We applied biotin goat anti-rat Ig antibody (BD Biosciences — Pharmingen, 559286) for secondary antibody. After TSA amplification, the Dako EnVision+ HRP/DAB System (catalog K4007, Dako) was used to produce localized, visible staining. All slides were incubated for equal amounts of time. They were then rinsed in dH2O for 2 minutes, counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, and coverslipped.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

After slides were deparaffinized and hydrated, sodium citrate antigen retrieval was performed using 0.1 M citric acid and 0.1 M sodium citrate. Slides were heated for 2 minutes in the microwave, cooled to room temperature and then washed gently with Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Slides were blocked (5% BSA solution containing 10% goat serum) and immunostained with rabbit anti-mouse fibrin(ogen) (1:1000) antibody (65) overnight at 4°C. Slides were then washed and incubated with 10 μg/ml of Alexa Fluor 647–labeled anti-rabbit antibody (Life Technologies 792514) in blocking buffer for 1 hour. Slides were counterstained with DAPI and coverslipped using mounting solution (PolySciences); fluorescent images were taken (NIKON AZ100, upright wide-field microscope). Slides incubated without primary antibodies served as negative controls.

van Gieson/von Kossa staining in plastic section

Undecalcified femurs of each mouse were fixed in paraformaldehyde and dehydrated in ascending alcohol concentrations and then embedded in methylmethacrylate as previously described (66). Sections of 7-μm thickness were cut on a Microtec rotation microtome (Techno-Med GmbH). Sections were stained by van Gieson/von Kossa procedures as described. Undecalcified sections of 4 μm were cut in the sagittal plane on a Microtec rotation microtome (Techno-Med GmbH).

Quantification of soft-tissue callus size

Hard- and soft-tissue callus, delineated by safranin O red staining, was traced on 5 histological step sections 200 μm apart as previously described, with the following changes (67). To determine the orientation of the 5 slides, the edge of the callus was visualized by identifying the first section with callus on both the medial and lateral femoral cortex, and the middle of the callus was determined by the pin space. Each of the specimen’s 5 sections was measured by 3 blinded reviewers, and results were then expressed as mm2 of the soft-tissue callus area. Image quantification for the soft-tissue callus was performed using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Quantification of fracture callus vascularity

To assess vascularity of the fracture callus, immunohistochemical staining for CD31 was performed at 14 DPF. Photographs of the distal and proximal ends of the fracture callus were taken under low magnification (×20), so that the entirety of fracture callus was collected. CD31 area was determined by using Photoshop (threshold 40) to select all CD31-positive staining from the background. CD31-positive staining was then imported into ImageJ, and the area of staining was calculated. To determine the number of CD31-positive vessels, 2 blinded observers counted CD31-positive vessels within the fracture callus. A vessel was defined as a structure with CD31 cells lining the lumen.

ASO treatment

ASO for fibrinogen (ISIS Pharmaceuticals Inc.) was administered to Plg–/– mice 2 weeks prior to fracture and throughout the course of this study at a concentration of 100 mg/kg subcutaneously weekly. Fibrinogen ASO (GCTTTGATCAGTTCTTTGGC) targets hepatic translation of the γ-chain of fibrinogen and has been shown to have no toxicity at this dose. As a control, the universal control ASO (CCTTCCCTGAAGGTTCCTCC), which has no homologies in the mouse genome, was administered subcutaneously at a concentration of 100 mg/kg weekly 2 weeks prior to fracture. Both ASOs were chemically modified with a phosphorothioate backbone that had 2′-O-methoxyethyl–modified nucleotides on the wings and a central deoxynucleotide gap. ASOs were synthesized using an Applied Biosystems 380B automated DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems) and purified as described previously (68). In order to identify the most potent fibrinogen ASOs for animal testing, ASOs were designed and tested in primary mouse hepatocytes for their ability to suppress mRNA levels of the respective targets.

Fibrinogen ELISA

To determine the effect of ASO for fibrinogen, we performed a fibrinogen ELISA. For collecting the plasma, we collected blood from mice using one-tenth volume of 0.1 M sodium citrate as an anticoagulant. After the collection of the blood in the centrifuge tubes, blood was centrifuged at 1,500 g for 15 minutes at room temperature. Supernatant was collected and centrifuged again at 13,000 g for 15 minutes at room temperature. Plasma in the supernatant was stored at –80°C until use. We measured the circulating fibrinogen levels using the manufacturer’s instructions (Immunology Consultants Laboratory Inc.).

FEA

To establish whether fibrin is essential to fracture repair, the segmented μCT images of the callus from WT and Fbg–/– mice at 42 DPF were converted to finite element models for an elastic FEA solver using a built-in code (FE-software v1.13, Scanco Medical). After ensuring that the callus segment (5 mm above and below fracture line) was aligned in the z or vertical direction (image stack rotated if tilted), one end was fully constrained (no movement) while the other end was prescribed a unit torque about the z-axis. Then, with the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio equal to 12 GPa and 0.3 for all mineralized tissue, the predicted callus strength was determined for the prescribed boundary conditions, assuming failure occurred when 2% of bone volume exceed 7000 microstrain. This approach is similar to other μCT-FEA studies involving torsion of rat femur callus (69) and compression testing of mouse vertebra (70). Since we assumed homogeneous material properties with elastic failure criteria, μCT-FEA effectively assessed the contribution of structure (callus size and union), not mineralization, to callus strength.

Radiographic quantification of fracture repair

We quantified fracture repair by measuring the 4 criteria: (a) mineralization, (b) organization, (c) union, and (d) remodeling. Samples were scored in a binary fashion with 0 meaning “does not meet the criteria” and 1 meaning “meets the criteria.” Both the anterior and posterior femur were scored, allowing for each radiograph to have a possibility of 8 total points. All x-rays were assessed in a blinded manner by 3 orthopedic clinicians from 1 to 6 weeks after fracture.

Statistics

Comparisons among the groups were performed using 1-way ANOVA with the least significant difference procedure used for analyzing 2 or multiple groups, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered significant for the differences between mean values.

Study approval

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Musculoskeletal Transplantation Foundation, the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, a Vanderbilt Orthopaedic Institute research grant, and the Caitlin Lovejoy Fund.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: G. Bhattacharjee and C. Zhao are employees of Isis Pharmaceuticals.

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2015;125(8):3117–3131. doi:10.1172/JCI80313.

References

- 1.Yuasa M, et al. The temporal and spatial development of vascularity in a healing displaced fracture. Bone. 2014;67:208–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerstenfeld LC, Cullinane DM, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88(5):873–884. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures In Adults. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, Nurden P, Nurden AT. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91(1):4–15. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martino MM, Briquez PS, Ranga A, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Heparin-binding domain of fibrin(ogen) binds growth factors and promotes tissue repair when incorporated within a synthetic matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(12):4563–4568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221602110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahni A, Francis CW. Vascular endothelial growth factor binds to fibrinogen and fibrin and stimulates endothelial cell proliferation. Blood. 2000;96(12):3772–3778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolar P, et al. The early fracture hematoma and its potential role in fracture healing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16(4):427–434. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Key JA, Conwell HE. The Management Of Fractures, Dislocations, And Sprains. St. Louis, Missouri, USA: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugge TH, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator is effective in fibrin clearance in the absence of its receptor or tissue-type plasminogen activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(12):5899–5904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romer J, et al. Impaired wound healing in mice with a disrupted plasminogen gene. Nat Med. 1996;2(3):287–292. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugge TH, Kombrinck KW, Flick MJ, Daugherty CC, Danton MJ, Degen JL. Loss of fibrinogen rescues mice from the pleiotropic effects of plasminogen deficiency. Cell. 1996;87(4):709–719. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole HA, et al. Fibrin accumulation secondary to loss of plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis drives inflammatory osteoporosis in mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(8):2222–2233. doi: 10.1002/art.38639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gunnar BJ, et al. United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States. 2nd ed. Park Ridge, Illinois, USA: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einhorn TA. Enhancement of fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):940–956. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebraheim NA, Martin A, Sochacki KR, Liu J. Nonunion of distal femoral fractures: a systematic review. Orthop Surg. 2013;5(1):46–50. doi: 10.1111/os.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Wakefield AE. Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(7):1359–1365. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cobb TK, Gabrielsen TA, Campbell DC, 2nd, Wallrichs SL, Ilstrup DM. Cigarette smoking and nonunion after ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15(2):64–67. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macey LR, Kana SM, Jingushi S, Terek RM, Borretos J, Bolander ME. Defects of early fracture-healing in experimental diabetes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):722–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruber R, Koch H, Doll BA, Tegtmeier F, Einhorn TA, Hollinger JO. Fracture healing in the elderly patient. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(11):1080–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kline AJ, Gruen GS, Pape HC, Tarkin IS, Irrgang JJ, Wukich DK. Early complications following the operative treatment of pilon fractures with and without diabetes. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(11):1042–1047. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez EK, et al. Predictive factors of distal femoral fracture nonunion after lateral locked plating: a retrospective multicenter case-control study of 283 fractures. Injury. 2014;45(3):554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foulk DA, Szabo RM. Diaphyseal humerus fractures: natural history and occurrence of nonunion. Orthopedics. 1995;18(4):333–335. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19950401-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castillo RC, Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Patterson BM, Group LS. Impact of smoking on fracture healing and risk of complications in limb-threatening open tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(3):151–157. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meade TW, Chakrabarti R, Haines AP, North WRS, Stirling Y. Characteristics affecting fibrinolytic activity and plasma fibrinogen concentrations. Br Med J. 1979;1(6157):153–156. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6157.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stepien E, Miszalski-Jamka T, Kapusta P, Tylko G, Pasowicz M. Beneficial effect of cigarette smoking cessation on fibrin clot properties. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32(2):177–182. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0593-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandolfi A, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 is increased in the arterial wall of type II diabetic subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(8):1378–1382. doi: 10.1161/hq0801.093667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maes C, et al. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell. 2010;19(2):329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gailit J, Clarke C, Newman D, Tonnesen MG, Mosesson MW, Clark RA. Human fibroblasts bind directly to fibrinogen at RGD sites through integrin α(v)β3. Exp Cell Res. 1997;232(1):118–126. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beamer B, Hettrich C, Lane J. Vascular endothelial growth factor: an essential component of angiogenesis and fracture healing. HSS J. 2010;6(1):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s11420-009-9129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerber HP, Vu TH, Ryan AM, Kowalski J, Werb Z, Ferrara N. VEGF couples hypertrophic cartilage remodeling, ossification and angiogenesis during endochondral bone formation. Nat Med. 1999;5(6):623–628. doi: 10.1038/9467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harper J, Klagsbrun M. Cartilage to bone — angiogenesis leads the way. Nat Med. 1999;5(6):617–618. doi: 10.1038/9460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brookes M, Landon DN. The juxta-epiphysial vessels in the long bones of foetal rats. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:336–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hausman MR, Schaffler MB, Majeska RJ. Prevention of fracture healing in rats by an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Bone. 2001;29(6):560–564. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00608-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burns DM. Epidemiology of smoking-induced cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46(1):11–29. doi: 10.1016/S0033-0620(03)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, et al. and Sowers JR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1134–1146. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.10.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meigs JB. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: translation from population to prevention: the Kelly West award lecture 2009. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(8):1865–1871. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purnell JQ, Zinman B, Brunzell JD, Group DER. The effect of excess weight gain with intensive diabetes mellitus treatment on cardiovascular disease risk factors and atherosclerosis in type 1 diabetes mellitus: results from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study (DCCT/EDIC) study. Circulation. 2013;127(2):180–187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.077487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willigendael EM, et al. Influence of smoking on incidence and prevalence of peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(6):1158–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammond JD, Verel D. Observations on the distribution and biological half-life of human fibrinogen. Br J Haematol. 1959;5:431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1959.tb04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ploplis VA, French EL, Carmeliet P, Collen D, Plow EF. Plasminogen deficiency differentially affects recruitment of inflammatory cell populations in mice. Blood. 1998;91(6):2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu AC, Raggatt LJ, Alexander KA, Pettit AR. Unraveling macrophage contributions to bone repair. Bonekey Rep. 2013;2:373. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khalil N, Corne S, Whitman C, Yacyshyn H. Plasmin regulates the activation of cell-associated latent TGF-β 1 secreted by rat alveolar macrophages after in vivo bleomycin injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15(2):252–259. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.2.8703482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yee JA, Yan L, Dominguez JC, Allan EH, Martin TJ. Plasminogen-dependent activation of latent transforming growth factor beta (TGF β) by growing cultures of osteoblast-like cells. J Cell Physiol. 1993;157(3):528–534. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041570312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roth D, et al. Plasmin modulates vascular endothelial growth factor-A-mediated angiogenesis during wound repair. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(2):670–684. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoenecker J, et al. 2010 Young Investigator Award winner: Therapeutic aprotinin stimulates osteoblast proliferation but inhibits differentiation and bone matrix mineralization. Spine. 2010;35(9):1008–1016. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d3cffe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawao N, et al. Plasminogen plays a crucial role in bone repair. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(7):1561–1574. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daci E, Udagawa N, Martin TJ, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G. The role of the plasminogen system in bone resorption in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(6):946–952. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Everts V, et al. Plasminogen activators are involved in the degradation of bone by osteoclasts. Bone. 2008;43(5):915–920. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification following combat-related trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(suppl 2):74–89. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Forsberg JA, Davis TA, Elster EA, Gimble JM. Burned to the bone. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(255):255fs37. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakellariou VI, Grigoriou E, Mavrogenis AF, Soucacos PN, Papagelopoulos PJ. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury: insight into the etiology and pathophysiology. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2012;12(4):230–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cipriano CA, Pill SG, Keenan MA. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(11):689–697. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aoki K, et al. Elevation of plasma free PAI-1 levels as an integrated endothelial response to severe burns. Burns. 2001;27(6):569–575. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(01)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hofstra JJ, et al. Pulmonary activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis after burn injuries and inhalation trauma. J Trauma. 2011;70(6):1389–1397. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820f85a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winther K, Gleerup G, Snorrason K, Biering-Sorensen F. Platelet function and fibrinolytic activity in cervical spinal cord injured patients. Thromb Res. 1992;65(3):469–474. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90178-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suelves M, et al. uPA deficiency exacerbates muscular dystrophy in MDX mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(6):1039–1051. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Douglas TE, et al. Enzymatically induced mineralization of platelet-rich fibrin. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100(5):1335–1346. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bugge TH, Flick MJ, Daugherty CC, Degen JL. Plasminogen deficiency causes severe thrombosis but is compatible with development and reproduction. Genes Dev. 1995;9(7):794–807. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suh TT, et al. Resolution of spontaneous bleeding events but failure of pregnancy in fibrinogen-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1995;9(16):2020–2033. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.16.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Neill KR, et al. Micro-computed tomography assessment of the progression of fracture healing in mice. Bone. 2012;50(6):1357–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cole HA, Yuasa M, Hawley G, Cates JM, Nyman JS, Schoenecker JG. Differential development of the distal and proximal femoral epiphysis and physis in mice. Bone. 2013;52(1):337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duvall CL, Taylor WR, Weiss D, Guldberg RE. Quantitative microcomputed tomography analysis of collateral vessel development after ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(1):H302–H310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00928.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duvall CL, Taylor WR, Weiss D, Wojtowicz AM, Guldberg RE. Impaired angiogenesis, early callus formation, and late stage remodeling in fracture healing of osteopontin-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(2):286–297. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dhillon RS, et al. PTH-enhanced structural allograft healing is associated with decreased angiopoietin-2-mediated arteriogenesis, mast cell accumulation, and fibrosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(3):586–597. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flick MJ, Du X, Degen JL. Fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 interactions regulate leukocyte function and innate immunity in vivo. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2004;229(11):1105–1110. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lehmann W, et al. Absence of mouse pleiotrophin does not affect bone formation in vivo. Bone. 2004;35(6):1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gerstenfeld LC, et al. Impaired fracture healing in the absence of TNF-alpha signaling: the role of TNF-alpha in endochondral cartilage resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(9):1584–1592. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker BF, et al. 2′-O-(2-Methoxy)ethyl-modified anti-intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) oligonucleotides selectively increase the ICAM-1 mRNA level and inhibit formation of the ICAM-1 translation initiation complex in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(18):11994–12000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shefelbine SJ, et al. Prediction of fracture callus mechanical properties using micro-CT images and voxel-based finite element analysis. Bone. 2005;36(3):480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nyman JS, et al. Predicting mouse vertebra strength with micro-computed tomography-derived finite element analysis. Bonekey Rep. 2015;4:664. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.