Abstract

Parathyroid carcinoma (PC) is a rare endocrine malignancy. The tumor is mostly functioning, causing severe primary hyperparathyroidism, with high serum calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. Nonfunctioning PC is extremely rare. We report a 50-year-old male patient who was referred to our Department for a right thyroid nodule, incidentally detected on carotid Doppler ultrasound scan, with a fine-needle aspiration cytology showing a follicular lesion. At the time of our evaluation, neck ultrasound showed a 1.3 cm right hypoechoic thyroid nodule with irregular margins and the absence of enlarged bilateral cervical lymph nodes. Thyroid function tests were normal. Serum calcium was normal and plasma PTH slightly above the upper limit of the normal range. The patients underwent right lobectomy. The intraoperative frozen-section pathological examination raised the suspicion of a PC. Definitive histology showed a markedly irregular infiltrative growth of the tumor with invasion of the thyroid tissue and cervical soft tissues. Immunostaining for thyroglobulin was negative, whereas staining for chromogranin A and PTH showed a strong reactivity. Based on the microscopic findings and the immunohistochemical profile, the tumor was diagnosed as a PC. Postoperative serum calcium and phosphate levels were in the normal range. One month after surgery, serum calcium and PTH were normal. Neck ultrasound and total body computed tomography scan were negative for local and metastatic disease. Eight months later, serum calcium was normal and plasma PTH level remained around the upper limit of normal range. Neck ultrasound did not show any pathological lesions. This is the first case of a nonfunctioning sporadic PC misdiagnosed prior of surgery as a follicular thyroid nodule. The parathyroid nature of the neck lesion could not be suspected before surgery. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may fail to distinguish a parathyroid tumor from a benign thyroid nodule because at FNAC, parathyroid and thyroid lesions have some morphological similarities. Histological criteria are not always sufficient for the differential diagnosis, which can definitely be established using immunohistochemistry.

Keywords: Primary hyperparathyroidism, Calcium metabolism, Chromogranin A, PTH, Parathyroid tumorigenesis

Background

Parathyroid carcinoma (PC) is a rare disease accounting for less than <1 % of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) [1, 2]. PC is usually a sporadic disease, but it has also been reported in familial PHPT, namely the hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome (HPT-JT) and, very rarely, in the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) [3]. At variance with the asymptomatic benign counterpart, patients with PC usually present markedly elevated serum calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels [4, 2]. The clinical features are mostly due to the effects of the excessive secretion of PTH by the functioning tumor rather than to the spread of tumor mass. The management of PC is primarily surgical, with en bloc resection of the tumor with involved adjacent structures [5, 4]. Rarely, parathyroid PC has been described in patients with normal levels of serum calcium and PTH (nonfunctioning PC) [6, 7] and, with the exception of one case in the setting of MEN-2A [8], all cases reported so far are sporadic [7]. The diagnosis of nonfunctioning PC has always been established at histology. Indeed, in the absence of hypercalcemia, the parathyroid origin of the neck lump cannot be established, and the lesion is usually diagnosed as thyroid or thymic carcinoma, because of locally advanced disease (palpable neck mass, dysphagia, hoarseness due to laryngeal nerve palsy).

The suspicion of the parathyroid origin of the excised tumor may raised by the finding at histology of feature suggestive of PC, namely uniform sheets of cells arranged in a lobular pattern separated by dense fibrous trabeculae, mitotic figures within tumor parenchymal, full thickness capsular invasion with growth into adjacent tissues, and extratumoral vascular invasion [9, 10]. Nevertheless, immunohistochemical studies for PTH, thyroglobulin, thyroid transcription factor 1, and calcitonin are usually performed to establish the definitive diagnosis.

Tumor resection is rarely curative and patients mostly die for the local invasion.

Case presentation

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the case report and any accompanying images.

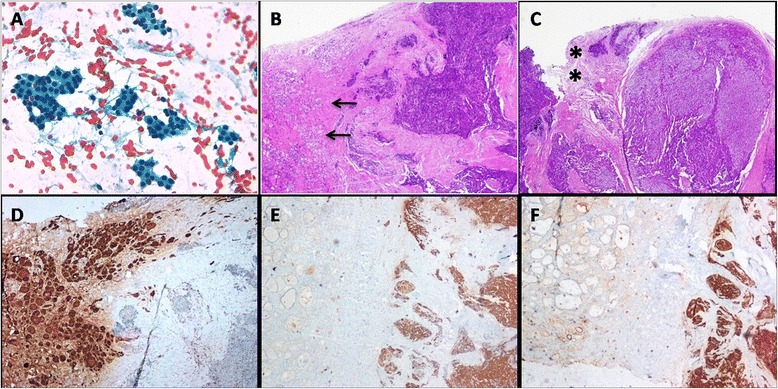

A 50-year-old male patient was admitted to our Department for a thyroid nodule on the right side of the neck, which was incidentally detected on carotid Doppler ultrasound scan. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) showed a follicular lesion. At the time of our evaluation, the patient was in good health. The medical history revealed hypertension, vitiligo, and celiac disease. On physical examination, a small nodule (1 cm) was palpable in the right thyroid lobe. No enlarged neck lymph nodes were palpable. Neck ultrasound showed a 1.3 cm hypoechoic nodule with irregular margins in the right thyroid lobe together with bilateral small thyroid nodules (4–5 mm) and the absence of enlarged cervical bilateral lymph nodes. Thyroid function tests were normal with the absence of thyroid autoantibodies. Serum calcium was normal (9.7 mg/dl; normal range, 8.4–10.4 mg/dL) and PTH, routinely measured together with serum calcium in our Center in patients undergoing thyroid surgery, slightly elevated (68 pg/mL (intact PTH, 2nd generation assay; normal range, 10–65 pg/mL)). The re-review of the original slides of FNAC confirmed a follicular lesion. In particular, the cytology of the nodule showed epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei organized in small cohesive clusters resembling microfollicles typically observed in thyroid follicular lesions were evident (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Cytological and histological specimens of nonfunctioning parathyroid carcinoma. a Cytological specimen showing epithelial cells organized in small cohesive clusters resembling thyroid microfollicles (Papanicolaou-stain, ×40 original magnification). b Histological section showing the neoplastic invasion of the neighboring thyroid tissue (arrows indicate the thyroid tissue; hematoxylin- and eosin-stain, ×2 original magnification). c Histological section showing the neoplastic invasion of the soft tissue surrounding the parathyroid tumor (*indicates the soft tissue; hematoxylin- and eosin-stain, ×2 original magnification). d–f Immunohistochemical stainings showing absence of immunoreactivity of the parathyroid tumor to thyroglobulin ((d), ×4 original magnification) and strong immunoreactivity to Chromogranin A ((e), ×4 original magnification) and parathyroid hormone (f), ×4 original magnification)

The patients underwent right lobectomy. During neck exploration, there were no macroscopic signs of local invasion. The intraoperative frozen-section pathological examination raised the suspicion of a PC. Definitive histology showed a markedly irregular infiltrative growth of the tumor with invasion of the thyroid tissue and cervical soft tissues (Fig. 1b, c). Immunostaining for thyroglobulin was negative, whereas staining for chromogranin A and PTH showed a strong reactivity (Fig. 1d–f). Based on the light microscopic findings and the immunohistochemical profile, the tumor was diagnosed as a PC. Postoperative serum calcium (8.7 mg/dl) and phosphate (3 mg/dl) levels were in the normal range. One month after surgery, serum calcium and plasma PTH were 9.6 mg/dL and 47 pg/mL, respectively. Neck ultrasound and total body computed tomography scan were negative for local and metastatic disease. Eight months later, serum calcium and plasma PTH levels were 9.1–9.2 mg/dl and 38–44 pg/ml (1–84 PTH 3rd generation assay, normal range, 8–40 pg/mL), respectively. Neck ultrasound did not show any pathological lesions. In order to exclude a familiar form of PHPT, in which PC may rarely occur as a nonfunctioning tumor [11], the screening of serum calcium and neck ultrasound in the first-degree relatives was normal.

Discussion

We describe a patient with a thyroid nodule discovered at carotid ultrasound, which underwent a routine diagnostic workout, which showed typical ultrasound features and cytological evidence of a follicular thyroid lesion. Surprisingly, the histological diagnosis revealed a PC.

In experienced hand, neck ultrasound has a high sensitivity in recognizing a eutopic parathyroid lesion, but it may fail when it has an ectopic location or is located within the thyroid [12, 13]. The latter condition occurred in the patient described herein as well as in the patient described by Kim et al., who reported a 53-year-old woman with a benign thyroid nodule at neck ultrasound, initially treated elsewhere with radiofrequency ablation, which was subsequently found to be a parathyroid adenoma at surgery [14].

FNAC may also fail to distinguish a parathyroid tumor from a benign thyroid nodule because at FNAC parathyroid and thyroid lesions have some morphological similarities [15]. Indeed, colloids and macrophages, which generally are found in a thyroid nodule, can be also be present in a parathyroid lesion. On the hand, parathyroid cells are generally smaller than thyroid cells and have less cytoplasm and more chromatin, but these are not a specific signs [16].

At surgery, the intraoperative frozen-section pathology in our patient suggested that the excised lesion was a PC and not a thyroid lesion. Despite this unexpected finding, the surgical procedure was limited to the right lobectomy because the surgeon could not find any macroscopic infiltration and/or enlarged lymph nodes. The diagnosis of a PC was confirmed by definitive histology and immunohistochemistry.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of a nonfunctioning sporadic PC misdiagnosed prior of surgery as a follicular thyroid nodule. The parathyroid nature of the neck lesion could not be suspected before surgery. Indeed, serum calcium concentration was normal and PTH slightly above the upper limit of the normal range. In interpreting this latter finding, we should keep in mind that the upper normal limit is usually fixed at the 97.5 percentile of the distribution of PTH among normal individuals; therefore, some normal individuals may have slightly elevated PTH. Another explanation could be that the slight increase of PTH level could be due to a low vitamin D status, which is a rather common condition [17]. Other secondary causes of elevation of PTH, namely thiazides diuretic use and reduced renal function, were excluded. The finding that plasma PTH remained around the upper limit of normal range following parathyroidectomy supports the concept that the parathyroid tumor was nonfunctioning.

The immunohistochemical finding of PTH protein in the tumor confirms its parathyroid origin as well as its ability to transcribe the PTH mRNA. The question of whether an active PTH molecule is synthesized but not secreted or whether the PTH molecule detected at immunostaining is not the mature form of PTH, which even if secreted cannot be measured in the serum, cannot be established. Unfortunately, we do not have fresh-frozen tissue for mRNA analysis nor preoperative serum/plasma samples to further investigate these possibilities. The patient described by Baba et al. may help to shed light on this matter [18]. These authors reported a patient with classical hypercalcemic PC, in whom 2 years after parathyroidectomy, a large supraclavicular mass was detected. The patient had normal serum calcium and PTH. The lesion was excised and a recurrent, apparently nonfunctioning PC was diagnosed at histology. The patient developed transient hypocalcemia after surgery. PTH mRNA was detected in the tumor. The absence of hypercalcemia suggested that the recurrence was nonfunctioning. The authors concluded that the identification of PTH mRNA in the tumor as well as the transient hypocalcemia after surgery suggest that PTH was synthesized and secreted, albeit in amounts too small to cause hypercalcemia, but sufficient to cause suppression of the presumably normal parathyroid glands [18]. At variance with this case, our patient did not show postoperative hypocalcemia, further supporting that the tumor did not secrete full-length PTH.

Nonfunctioning PC is diagnosed in most patients in the sixth or seventh decade (age range 27–71 years) [7, 19]. The tumor size is variable but ranges between 5 and 11 cm, and in almost half of the cases, loco regional spread into thyroid, cervical soft tissues and superior mediastinum is usually present at diagnosis [7, 19]. At variance, in our patient, the diagnosis was done at an earlier age (50 years) and the tumor size was 13 mm, likely because the patient was submitted to surgery for a follicular thyroid lesion.

The histological diagnosis of PC is currently restricted to lesions showing unequivocal extra-parathyroidal growth, as evidenced by perineural invasion, full thickness capsular invasion with growth into adjacent tissues, extratumoral vascular invasion, or metastasis. The histological criteria were all present in the tumor of our patient [9]. Several immunohistochemical markers have been evaluated to further improve the diagnostic accuracy of a nonfunctioning PC [20, 21]. Positive staining of chromogranin A and synaptophysin and negative staining of thyroglobulin has been reported in nonfunctioning PC [21, 20, 22]. In our case, a positive staining for PTH and chromogranin A, and negative staining for thyroglobulin, confirmed the parathyroid nature of the tumor. Therefore, the accurate diagnosis of nonfunctioning PC should be made by considering the combination of clinical presentations, tissue morphologic structure, and immunohistological staining.

Limited information is available on the follow-up of patients with nonfunctioning PC. Recurrences occurred in about half of the patients (7), but the majority (about 80 %) was alive when reported in the literature, even though the follow-up was rather short; only four patients were followed for more than 5 years after the initial surgery [7, 19]. Long-term follow-up data and information on mortality are not available, but the advance stage of the PC at diagnosis likely predict a poor prognosis, worse than that of patients with classical hypercalcemic PC, in whom the disease extension is more limited at time of diagnosis (metastases to lymph nodes (<5 %) or distant sites (<2 %)) [2, 23]. Even though during the follow-up, the tumor usually spreads to cervical nodes (30 %) and lung (40 %) and less frequently to liver and bone (10 %); the overall survival is of about 72 and 50 % at 5 and 10 years, respectively [23, 6].

Conclusions

This is the first case of a nonfunctioning sporadic PC misdiagnosed prior of surgery as a follicular thyroid nodule. The parathyroid nature of the neck lesion could not be suspected before surgery. FNAC may fail to distinguish a parathyroid tumor from a benign thyroid nodule because at FNAC, parathyroid and thyroid lesions have some morphological similarities. Histological criteria are not always sufficient for the differential diagnosis, which can definitely be established using immunohistochemistry. The reported case may likely contribute to enlarge the expanding clinical spectrum of nonfunctioning PC.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted without funding.

Abbreviations

- FNAC

fine-needle aspiration cytology

- HPT-JT

hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome

- MEN1

multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1

- PC

parathyroid carcinoma

- PHPT

primary hyperparathyroidism

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FC and CM carried out the study design. FC and GF conducted the study. GF and PM conducted the thyroid surgery. SM, AC, LT, and FB collected the data. FC, CM, LT, FB, and PM interpreted the data. FC and CM drafted the manuscript. FC, CM, GF, LT, FB, and PM revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Filomena Cetani, Phone: +39050995040, Email: cetani@endoc.med.unipi.it.

Gianluca Frustaci, Email: gianlucafrustaci@libero.it.

Liborio Torregrossa, Email: libo.torregrossa@gmail.com.

Silvia Magno, Email: silvia.magno@alice.it.

Fulvio Basolo, Email: fulvio.basolo@med.unipi.it.

Alberto Campomori, Email: acampomori@gmail.com.

Paolo Miccoli, Email: paolo.miccoli@dc.unipi.it.

Claudio Marcocci, Email: claudio.marcocci@med.unipi.it.

References

- 1.Marcocci C, Cetani F. Clinical practice. Primary hyperparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2389–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1106636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcocci C, Cetani F, Rubin MR, Silverberg SJ, Pinchera A, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid carcinoma. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1869–80. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx SJ, Simonds WF, Agarwal SK, Burns AL, Weinstein LS, Cochran C, et al. Hyperparathyroidism in hereditary syndromes: special expressions and special managements. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(Suppl 2):N37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shane E. Clinical review 122: parathyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:485–93. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrogini E, Cetani F, Cianferotti L, Vignali E, Banti C, Viccica G, et al. Surgery or surveillance for mild asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3114–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harari A, Waring A, Fernandez-Ranvier G, Hwang J, Suh I, Mitmaker E, et al. Parathyroid carcinoma: a 43-year outcome and survival analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3679–86. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkins BJ, Lewis JS., Jr Non-functional parathyroid carcinoma: a review of the literature and report of a case requiring extensive surgery. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:140–9. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szurkowska M, Szafraniec K, Gilis-Januszewska A, Pach D, Krzentowska A, Szybinski Z, et al. Prevalence of the glucose metabolism disturbances in screening of adult inhabitants of Krakow. Przegl Lek. 2006;63:728–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLellis RA. Parathyroid tumors and related disorders. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:S78–93. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schantz A, Castleman B. Parathyroid carcinoma. A study of 70 cases. Cancer. 1973;31:600–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197303)31:3<600::AID-CNCR2820310316>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarnieri V, Scillitani A, Muscarella LA, Battista C, Bonfitto N, Bisceglia M, et al. Diagnosis of parathyroid tumors in familial isolated hyperparathyroidism with HRPT2 mutation: implications for cancer surveillance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2827–32. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitson BA, Broadie TA. Preoperative ultrasound and nuclear medicine studies improve the accuracy in localization of adenoma in hyperparathyroidism. Surg Today. 2008;38:222–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haber RS, Kim CK, Inabnet WB. Ultrasonography for preoperative localization of enlarged parathyroid glands in primary hyperparathyroidism: comparison with (99m)technetium sestamibi scintigraphy. Clin Endocrinol. 2002;57:241–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HS, Choi BH, Park JR, Hahm JR, Jung JH, Kim SK, et al. Delayed surgery for parathyroid adenoma misdiagnosed as a thyroid nodule and treated with radiofrequency ablation. Endocrinol Metab. 2013;28:231–5. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heo I, Park S, Jung CW, Koh JS, Lee SS, Seol H, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of parathyroid lesions. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:466–71. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieu D. Cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of parathyroid lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:327–32. doi: 10.1002/dc.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cusano NE, Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Normocalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baba H, Kishihara M, Tohmon M, Fukase M, Kizaki T, Okada S, et al. Identification of parathyroid hormone messenger ribonucleic acid in an apparently nonfunctioning parathyroid carcinoma transformed from a parathyroid carcinoma with hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:247–52. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-2-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchida N, Ishiguro K, Suda T, Horie Y, Nishimura M. Metastatic breast tumor due to nonfunctional parathyroid carcinoma. Int Canc Conf J. 2012;1:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s13691-011-0008-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krvavica A, Kovacic M, Baraka I, Rudic M. Non-functioning parathyroid gland carcinoma: case report. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:233–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura Y, Kataoka H, Sakoda T, Horie Y, Kitano H. Nonfunctional parathyroid carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15:500–3. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo H, Mai R, Liu M, Peng H, Yang X, Wu M, et al. Nonfunctional parathyroid carcinoma after breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e122–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.7227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cetani F, Banti C, Pardi E, Borsari S, Viacava P, Miccoli P, et al. CDC73 mutational status and loss of parafibromin in the outcome of parathyroid cancer. Endocr Connect. 2013;2:186–95. doi: 10.1530/EC-13-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]